Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment 2). Finally, the study shows that an individual's autistic traits are negatively correlated with the BM-AVI congruency effect.

Strengths:

The three experiments are well designed and the various conditions are well controlled. The rationale of the study is clear, and the manuscript is pleasant to read. The analysis choices are easy to follow, and mostly appropriate.

Weaknesses:

There is a concern of double-dipping in one of the tests (Experiment 2, Figure 3: interaction of Upright/Inverted X Congruent/Incongruent). I raised this concern on the original submission, and it has not been resolved properly. The follow-up statistical test (after channel selection using the interaction contrast permutation test) still is geared towards that same contrast, even though the latter is now being tested differently. (Perhaps not explicitly testing the interaction, but in essence still testing the same.) A very simple solution would be to remove the post-hoc statistical tests and simply acknowledge that you're comparing simple means, while the statistical assessment was already taken care of using the permutation test. (In other words: the data appear compelling because of the cluster test, but NOT because of the subsequent t-tests.)

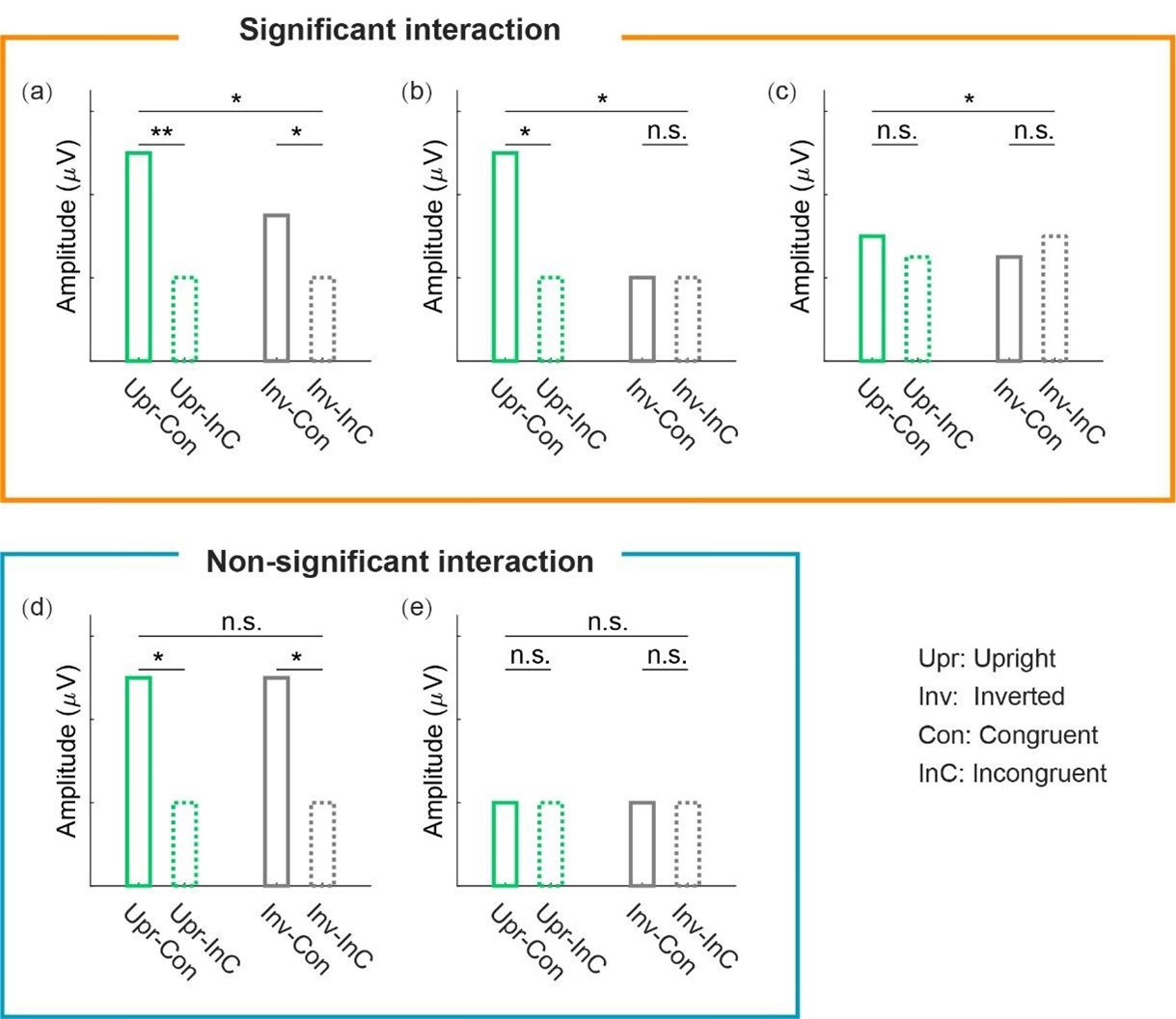

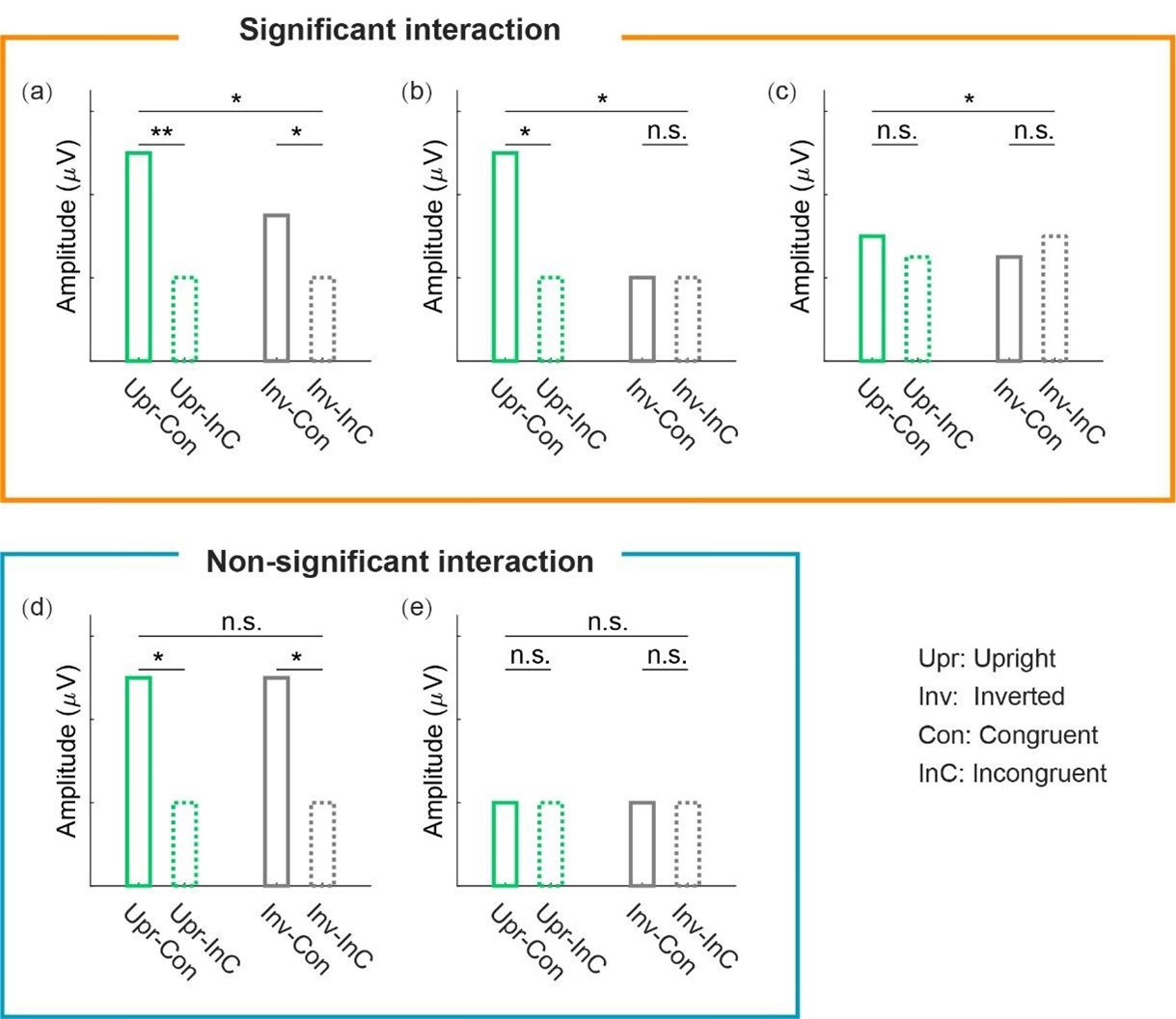

We are sorry that we did not explain this issue clearly before, which might have caused some misunderstanding. When performing the cluster-based permutation test, we only tested whether the audiovisual congruency effect (congruent vs. incongruent) between the upright and inverted conditions was significantly different [i.e., (UprCon – UprInc) vs. (InvCon – InvInc)], without conducting extra statistical analyses on whether the congruency effect was significant in each orientation condition. Such an analysis yielded a cluster with a significant interaction between audiovisual integration and BM orientation for the cortical tracking effect at 1Hz (but not at 2Hz). However, this does not provide valid information about whether the audiovisual congruency effect at this cluster is significant in each orientation condition, given that a significant interaction effect may result from various patterns of data across conditions: such as significant congruency effects in both orientation conditions (Author response image 1a), a significant congruency effect in the upright condition and a non-significant effect in the inverted condition (Author response image 1b), or even non-significant yet opposite effects in the two conditions (Author response image 1c). Here, our results conform to the second pattern, indicating that cortical tracking of the high-order gait cycles involves a domain-specific process exclusively engaged in the AVI of BM. In a similar vein, the non-significant interaction found at 2Hz does not necessarily indicate that the congruency effect is non-significant in each orientation condition (Author response image 1f&e). Indeed, the congruency effect was significant in both the upright and inverted conditions at 2Hz in our study despite the non-significant interaction, suggesting that neural tracking of the lower-order step cycles is associated with a domain-general AVI process mostly driven by temporal correspondence in physical stimuli.

Therefore, we need to perform subsequent t-tests to examine the significance of the simple effects in the two orientation conditions, which do not duplicate the clusterbased permutation test (for interaction only) and cause no double-dipping. Results from interaction and simple effects, put together, provide solid evidence that the cortical tracking of higher-order and lower-order rhythms involves BM-specific and domaingeneral audiovisual processing, respectively.

To avoid ambiguity, we have removed the sentence “We calculated the audiovisual congruency effect for the upright and the inverted conditions” (line 194, which referred to the calculation of the indices rather than any statistical tests) from the manuscript. We have also clarified the meanings of the findings based on the interaction and simple effects together at the two temporal scales, respectively (Lines 205-207; Lines 213-215).

Author response image 1.

Examples of different patterns of data yielding a significant or nonsignificant interaction effect.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely clear. The study involves multiple experiments with different participant groups. Each experiment involves specific considered changes to the experimental paradigm that both replicate the previous experiment's finding yet extend it in a relevant manner.

Weaknesses:

In the revised version of the paper, the manuscript better relays the results and anticipates analyses, and this version adequately resolves some concerns I had about analysis details. Still, it is my view that the findings of the study are basic neural correlate results that do not provide insights into neural mechanisms or the causal relevance of neural effects towards behavior and cognition. The presence of an inversion effect suggests that the supra-additivity is related to cognition, but that leaves open whether any detected neural pattern is actually consequential for multi-sensory integration (i.e., correlation is not causation). In other words, the fact that frequency-specific neural responses to the [audio & visual] condition are stronger than those to [audio] and [visual] combined does not mean this has implications for behavioral performance. While the correlation to autism traits could suggest some relation to behavior and is interesting in its own right, this correlation is a highly indirect way of assessing behavioral relevance. It would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to the processing of biological motion to justify the claim that inputs are being integrated in the service of behavior. Under either framework, cortical tracking or entrainment, the causal relevance of neural findings toward cognition is lacking.

Overall, I believe this study finds neural correlates of biological motion, and it is possible that such neural correlates relate to behaviorally relevant neural mechanisms, but based on the current task and associated analyses this has not been shown.

Thank you for providing these thoughtful comments regarding the theoretical implications of our neural findings. Previous behavioral evidence highlights the specificity of the audiovisual integration (AVI) of biological motion (BM) and reveals the impairment of such ability in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. However, the neural implementation underlying the AVI of BM, its specificity, and its association with autistic traits remain largely unknown. The current study aimed to address these issues.

It is noteworthy that the operation of multisensory integration does not always depend on specific tasks, as our brains tend to integrate signals from different sensory modalities even when there is no explicit task. Hence, many studies have investigated multisensory integration at the neural level without examining its correlation with behavioral performance. For example, the widely known super-additivity mode for multisensory integration proposed by Perrault and colleagues was based on single-cell recording findings without behavioral tasks (Perrault et al., 2003, 2005). As we mentioned in the manuscript, the super-additive and sub-additive modes indicate non-linear interaction processing, either with potentiated neural activation to facilitate the perception or detection of near-threshold signals (super-additive) or a deactivation mechanism to minimize the processing of redundant information cross-modally (subadditive) (Laurienti et al., 2005; Metzger et al., 2020; Stanford et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2003). Meanwhile, the additive integration mode represents a linear combination between two modalities. Distinguishing among these integration modes helps elucidate the neural mechanism underlying AVI in specific contexts, even though sometimes, the neural-level AVI effects do not directly correspond to a significant behavioral-level AVI effect (Ahmed et al., 2023; Metzger et al., 2020). In the current study, we unveiled the dissociation of multisensory integration modes between neural responses at two temporal scales (Exps. 1a & 1b), which may involve the cooperation of a domain-specific and a domain-general AVI processes (Exp. 2). While these findings were not expected to be captured by a single behavioral index, they revealed the multifaceted mechanism whereby hierarchical cortical activity supports audiovisual BM integration. They also advance our understanding of the emerging view that multi-timescale neural dynamics coordinate multisensory integration (Senkowski & Engel, 2024), especially from the perspective of natural stimuli processing.

Meanwhile, our finding that the cortical tracking of higher-order rhythmic structure in audiovisual BM specifically correlated with individual autistic traits extends previous behavioral evidence that ASD children exhibited reduced orienting to audiovisual synchrony in BM (Falck-Ytter et al., 2018), offering new evidence that individual differences in audiovisual BM processing are present at the neural level and associated with autistic traits. This finding opens the possibility of utilizing the cortical tracking of BM as a potential neural maker to assist the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (see more details in our Discussion Lines 334-346).

However, despite the main objective of the current study focusing on the neural processing of BM, we agree with the reviewer that it would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to BM perception, for further justifying that inputs are being integrated in the service of behavior. In the current study, we adopted a color-change detection task entirely unrelated to audiovisual correspondence but only for maintaining participants’ attention. The advantage of this design is that it allows us to investigate whether and how the human brain integrates audiovisual BM information under task-irrelevant settings, as people in daily life can integrate such information even without a relevant task. However, this advantage is accompanied by a limitation: the task does not facilitate the direct examination of the correlation between neural responses and behavioral performance, since the task performance was generally high (mean accuracy >98% in all experiments). Future research could investigate this issue by introducing behavioral tasks more relevant to BM perception (e.g., Shen et al., 2023). They could also apply advanced neuromodulation techniques to elucidate the causal relevance of the cortical tracking effect to behavior (e.g., Ko sem et al., 2018, 2020).

We have discussed the abovementioned points as a separate paragraph in the revised manuscript (Lines 322-333). In addition, since the scope of the current study does not involve a causal correlation with behavioral performance, we have removed or modified the descriptions related to "functional relevance" in the manuscript (Abstract; Introduction, lines 101-103; Results, lines 239; Discussion, line 336; Supplementary Information, line 794、803). Moreover, we have strengthened the descriptions of the theoretical implications of the current findings in the abstract.

We hope these changes adequately address your concern.

References

Ahmed, F., Nidiffer, A. R., O’Sullivan, A. E., Zuk, N. J., & Lalor, E. C. (2023). The integration of continuous audio and visual speech in a cocktail-party environment depends on attention. Neuroimage, 274, 120143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.120143

Falck-Ytter, T., Nystro m, P., Gredeba ck, G., Gliga, T., Bo lte, S., & the EASE team. (2018). Reduced orienting to audiovisual synchrony in infancy predicts autism diagnosis at 3 years of age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(8), 872–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12863

Ko sem, A., Bosker, H., Jensen, O., Hagoort, P., & Riecke, L. (2020). Biasing the Perception of Spoken Words with Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 32, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01579

Ko sem, A., Bosker, H. R., Takashima, A., Meyer, A., Jensen, O., & Hagoort, P. (2018). Neural Entrainment Determines the Words We Hear. Current Biology, 28(18), 2867-2875.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.023

Laurienti, P. J., Perrault, T. J., Stanford, T. R., Wallace, M. T., & Stein, B. E. (2005). On the use of superadditivity as a metric for characterizing multisensory integration in functional neuroimaging studies. Experimental Brain Research, 166(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-005-2370-2

Metzger, B. A., Magnotti, J. F., Wang, Z., Nesbitt, E., Karas, P. J., Yoshor, D., & Beauchamp, M. S. (2020). Responses to Visual Speech in Human Posterior Superior Temporal Gyrus Examined with iEEG Deconvolution. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 40(36), 6938–6948. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0279-20.2020

Perrault, T. J., Vaughan, J. W., Stein, B. E., & Wallace, M. T. (2003). Neuron-Specific Response Characteristics Predict the Magnitude of Multisensory Integration. Journal of Neurophysiology, 90(6), 4022–4026. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00494.2003

Perrault, T. J., Vaughan, J. W., Stein, B. E., & Wallace, M. T. (2005). Superior Colliculus Neurons Use Distinct Operational Modes in the Integration of Multisensory Stimuli. Journal of Neurophysiology, 93(5), 2575–2586. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00926.2004

Senkowski, D., & Engel, A. K. (2024). Multi-timescale neural dynamics for multisensory integration. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 25(9), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-024-00845-7

Shen, L., Lu, X., Wang, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2023). Audiovisual correspondence facilitates the visual search for biological motion. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 30(6), 2272–2281. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02308-z

Stanford, T. R., Quessy, S., & Stein, B. E. (2005). Evaluating the Operations Underlying Multisensory Integration in the Cat Superior Colliculus. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(28), 6499–6508. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5095-04.2005

Wright, T. M., Pelphrey, K. A., Allison, T., McKeown, M. J., & McCarthy, G. (2003). Polysensory Interactions along Lateral Temporal Regions Evoked by Audiovisual Speech. Cerebral Cortex, 13(10), 1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/13.10.1034