Author response:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, the authors investigated the effect of chronic activation of dopamine neurons using chemogenetics. Using Gq-DREADDs, the authors chronically activated midbrain dopamine neurons and observed that these neurons, particularly their axons, exhibit increased vulnerability and degeneration, resembling the pathological symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Baseline calcium levels in midbrain dopamine neurons were also significantly elevated following the chronic activation. Lastly, to identify cellular and circuit-level changes in response to dopaminergic neuronal degeneration caused by chronic activation, the authors employed spatial genomics (Visium) and revealed comprehensive changes in gene expression in the mouse model subjected to chronic activation. In conclusion, this study presents novel data on the consequences of chronic hyperactivation of midbrain dopamine neurons.

Strengths:

This study provides direct evidence that the chronic activation of dopamine neurons is toxic and gives rise to neurodegeneration. In addition, the authors achieved the chronic activation of dopamine neurons using water application of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO), a method not commonly employed by researchers. This approach may offer new insights into pathophysiological alterations of dopamine neurons in Parkinson's disease. The authors also utilized state-of-the-art spatial gene expression analysis, which can provide valuable information for other researchers studying dopamine neurons. Although the authors did not elucidate the mechanisms underlying dopaminergic neuronal and axonal death, they presented a substantial number of intriguing ideas in their discussion, which are worth further investigation.

We thank the reviewer for these positive comments.

Weaknesses:

Many claims raised in this paper are only partially supported by the experimental results. So, additional data are necessary to strengthen the claims. The effects of chronic activation of dopamine neurons are intriguing; however, this paper does not go beyond reporting phenomena. It lacks a comprehensive explanation for the degeneration of dopamine neurons and their axons. While the authors proposed possible mechanisms for the degeneration in their discussion, such as differentially expressed genes, these remain experimentally unexplored.

We thank the reviewer for this review. We do believe that the manuscript has a mechanistic component, as the central experiments involve direct manipulation of neuronal activity, and we show an increase in calcium levels and gene expression changes in dopamine neurons that coincide with the degeneration. However, we agree that deeper mechanistic investigation would strengthen the conclusions of the paper. We have planned several important revisions, including the addition of CNO behavioral controls, manipulation of intracellular calcium using isradipine, additional transcriptomics experiments and further validation of findings. We anticipate that these additions will significantly bolster the conclusions of the paper.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

Rademacher et al. present a paper showing that chronic chemogenetic excitation of dopaminergic neurons in the mouse midbrain results in differential degeneration of axons and somas across distinct regions (SNc vs VTA). These findings are important. This mouse model also has the advantage of showing a axon-first degeneration over an experimentally-useful time course (2-4 weeks). 2. The findings that direct excitation of dopaminergic neurons causes differential degeneration sheds light on the mechanisms of dopaminergic neuron selective vulnerability. The evidence that activation of dopaminergic neurons causes degeneration and alters mRNA expression is convincing, as the authors use both vehicle and CNO control groups, but the evidence that chronic dopaminergic activation alters circadian rhythm and motor behavior is incomplete as the authors did not run a CNO-control condition in these experiments.

Strengths:

This is an exciting and important paper.

The paper compares mouse transcriptomics with human patient data.

It shows that selective degeneration can occur across the midbrain dopaminergic neurons even in the absence of a genetic, prion, or toxin neurodegeneration mechanism.

We thank the reviewer for these insightful comments.

Weaknesses:

Major concerns:

(1) The lack of a CNO-positive, DREADD-negative control group in the behavioral experiments is the main limitation in interpreting the behavioral data. Without knowing whether CNO on its own has an impact on circadian rhythm or motor activity, the certainty that dopaminergic hyperactivity is causing these effects is lacking.

This is an important point. Although we show that CNO does not produce degeneration of DA neuron terminals, we do not exclude a contribution to the behavioral changes. We agree that this behavioral control is necessary, and will address it in revision with a CNO-only running wheel cohort.

(2) One of the most exciting things about this paper is that the SNc degenerates more strongly than the VTA when both regions are, in theory, excited to the same extent. However, it is not perfectly clear that both regions respond to CNO to the same extent. The electrophysiological data showing CNO responsiveness is only conducted in the SNc. If the VTA response is significantly reduced vs the SNc response, then the selectivity of the SNc degeneration could just be because the SNc was more hyperactive than the VTA. Electrophysiology experiments comparing the VTA and SNc response to CNO could support the idea that the SNc has substantial intrinsic vulnerability factors compared to the VTA.

We agree that additional electrophysiology conducted in the VTA dopamine neurons would meaningfully add to our understanding of the selective vulnerability in this model, and will complete these experiments in revision.

(3) The mice have access to a running wheel for the circadian rhythm experiments. Running has been shown to alter the dopaminergic system (Bastioli et al., 2022) and so the authors should clarify whether the histology, electrophysiology, fiber photometry, and transcriptomics data are conducted on mice that have been running or sedentary.

We will explicitly clarify which mice had access to a running wheel in our revision. Briefly, mice for histology, electrophysiology, and transcriptomics all had access to a running wheel during their treatment. The mice used for photometry underwent about 7 days of running wheel access approximately 3 weeks prior to the beginning of the experiment. The photometry headcaps sterically prevented mice from having access to a running wheel in their home cage.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, Rademacher and colleagues examined the effect on the integrity of the dopamine system in mice of chronically stimulating dopamine neurons using a chemogenetic approach. They find that one to two weeks of constant exposure to the chemogenetic activator CNO leads to a decrease in the density of tyrosine hydroxylase staining in striatal brain sections and to a small reduction of the global population of tyrosine hydroxylase positive neurons in the ventral midbrain. They also report alterations in gene expression in both regions using a spatial transcriptomics approach. Globally, the work is well done and valuable and some of the conclusions are interesting. However, the conceptual advance is perhaps a bit limited in the sense that there is extensive previous work in the literature showing that excessive depolarization of multiple types of neurons associated with intracellular calcium elevations promotes neuronal degeneration. The present work adds to this by showing evidence of a similar phenomenon in dopamine neurons.

We thank the reviewer for the careful and thoughtful review of our manuscript.

While extensive depolarization and associated intracellular calcium elevations promotes degeneration generally, we emphasize that the process we describe is novel. Indeed, prior studies delivering chronic DREADDs to vulnerable neurons in models of Alzheimer’s disease did not report an increase in neurodegeneration, despite seeing changes in protein aggregation (e.g. Yuan and Grutzendler, J Neurosci 2016, PMID: 26758850; Hussaini et al., PLOS Bio 2020, PMID: 32822389). Further, a critical finding from our study is that in our paradigm, this stressor does not impact all dopamine neurons equally, as the SNc DA neurons are more vulnerable than the VTA, mirroring selective vulnerability characteristic of Parkinson’s disease. This is consistent with a large body of literature that SNc dopamine neurons are less capable of handling large energetic and calcium loads compared to neighboring VTA neurons, and the finding that chronically altered activity is sufficient to drive this preferential loss is novel.

In addition, we are not aware of prior studies that have chronically activated DREADDs to produce neurodegeneration. Other studies have shown that acute excitotoxic stressors can produce neuronal degeneration, but the chronic increase in activity is central to our approach.

In terms of the mechanisms explaining the neuronal loss observed after 2 to 4 weeks of chemogenetic activation, it would be important to consider that dopamine neurons are known from a lot of previous literature to undergo a decrease in firing through a depolarization-block mechanism when chronically depolarized. Is it possible that such a phenomenon explains much of the results observed in the present study? It would be important to consider this in the manuscript.

As discussed in greater detail in the results section below, our data suggests this may not be a prominent feature in our model. However, we cannot rule out a contribution of depolarization block, and will expand on the discussion of this possibility in the revised manuscript.

The relevance to Parkinson's disease (PD) is also not totally clear because there is not a lot of previous solid evidence showing that the firing of dopamine neurons is increased in PD, either in human subjects or in mouse models of the disease. As such, it is not clear if the present work is really modelling something that could happen in PD in humans.

We completely agree that evidence of increased dopamine neuron activity from human PD patients is lacking and the existing data are difficult to interpret without human controls. However, as we outline in the manuscript, multiple lines of evidence suggest that the activity level of dopamine neurons almost certainly does change in PD. Therefore, it is very important that we understand how changes in the level of neural activity influence the degeneration of DA neurons. In this paper we examine the impact of increased activity. Increased activity may be compensatory after initial dopamine neuron loss, or may be an initial driver of death (Rademacher & Nakamura, Exp Neurol 2024, PMID: 38092187). Beyond what is already discussed in the manuscript, additional support for increased activity in PD models include:

- Elevated firing rates in asymptomatic MitoPark mice (Good et al., FASEB J 2011, PMID: 21233488)

- Increased frequency of spontaneous firing in patient-derived iPSC dopamine neurons and primary mouse dopamine neurons that overexpress synuclein (Lin et al., Acta Neuropath Comm 2021, PMID: 34099060)

- Increased spontaneous firing in dopamine neurons of rats injected with synuclein preformed fibrils compared to sham (Tozzi et al., Brain 2021, PMID: 34297092)

We will include and further discuss these important examples in our revision.

Similarly, in future studies, it will also be important to study the impact of decreasing DA neuron activity. There will be additional levels of complexity to accurately model changes in PD, which may differ between subtypes of the disease, the disease stage, and the subtype of dopamine neuron. Our study models the possibility of chronically increased pacemaking, and interpretation of our results will be informed as we learn more about how the activity of DA neurons changes in humans in PD. We will discuss and elaborate on these important points in the revision.

Comments on the introduction:

The introduction cites a 1990 paper from the lab of Anthony Grace as support of the fact that DA neurons increase their firing rate in PD models. However, in this 1990 paper, the authors stated that: "With respect to DA cell activity, depletions of up to 96% of striatal DA did not result in substantial alterations in the proportion of DA neurons active, their mean firing rate, or their firing pattern. Increases in these parameters only occurred when striatal DA depletions exceeded 96%." Such results argue that an increase in firing rate is most likely to be a consequence of the almost complete loss of dopamine neurons rather than an initial driver of neuronal loss. The present introduction would thus benefit from being revised to clarify the overriding hypothesis and rationale in relation to PD and better represent the findings of the paper by Hollerman and Grace.

We agree that the findings of Hollerman and Grace support compensatory changes in dopamine neuron activity in response to loss of dopamine neurons, rather than informing whether dopamine neuron loss can also be an initial driver of activity. We will clarify this point in our revision. In addition, the results of other studies on this point are mixed: a 50% reduction in dopamine neurons didn’t alter firing rate or bursting (Harden and Grace, J Neurosci 1995, PMID: 7666198; Bilbao et al, Brain Res 2006, PMID: 16574080), while a 40% loss was found to increase firing rate and bursting (Chen et al, Brain Res 2009. PMID: 19545547) and larger reductions alter burst firing (Hollerman & Grace, Brain Res 1990, PMID: 2126975; Stachowiak et al, J Neurosci 1987, PMID: 3110381). Importantly, even if compensatory, such late-stage increases in dopamine neuron activity may contribute to disease progression and drive a vicious cycle of degeneration in surviving neurons. In addition, we also don’t know how the threshold of dopamine neuron loss and altered activity may differ between mice and humans, and PD patients do not present with clinical symptoms until ~30-60% of nigral neurons are lost (Burke & O’Malley, Exp Neurol 2013, PMID: 22285449; Shulman et al, Annu Rev Pathol 2011, PMID: 21034221).

Other lines of evidence support the potential role of hyperactivity in disease initiation, including increased activity before dopamine neuron loss in MitoPark mice (Good et al., FASEB J 2011, PMID: 21233488), increased spontaneous firing in patient-derived iPSC dopamine neurons (Lin et al., Acta Neuropath Comm 2021, PMID: 34099060), and increased activity observed in genetic models of PD (Bishop et al., J Neurophysiol 2010, PMID: 20926611; Regoni et al., Cell Death Dis 2020, PMID: 33173027).

It would be good that the introduction refers to some of the literature on the links between excessive neuronal activity, calcium, and neurodegeneration. There is a large literature on this and referring to it would help frame the work and its novelty in a broader context.

We agree that a discussion of hyperactivity, calcium, and neurodegeneration would benefit the introduction. While we briefly discuss calcium and neurodegeneration in the discussion, we will expand on this literature in both the introduction and discussion sections. We will carefully review and contextualize our work within existing frameworks of calcium and neurodegeneration (e.g. Surmeier & Schumacker, J Biol Chem 2013, PMID: 23086948; Verma et al., Transl Neurodegener 2022, PMID: 35078537). We believe that the novelty of our study lies in 1) a chronic chemogenetic activation paradigm via drinking water, 2) demonstrating selective vulnerability of dopamine neurons as a result of altering their activity/excitability alone, and 3) comparing mouse and human spatial transcriptomics.

Comments on the results section:

The running wheel results of Figure 1 suggest that the CNO treatment caused a brief increase in running on the first day after which there was a strong decrease during the subsequent days in the active phase. This observation is also in line with the appearance of a depolarization block.

The authors examined many basic electrophysiological parameters of recorded dopamine neurons in acute brain slices. However, it is surprising that they did not report the resting membrane potential, or the input resistance. It would be important that this be added because these two parameters provide key information on the basal excitability of the recorded neurons. They would also allow us to obtain insight into the possibility that the neurons are chronically depolarized and thus in depolarization block.

We do report the input resistance in Supplemental Figure 1C, which was unchanged in CNO-treated animals compared to controls. We did not report the resting membrane potential because many of the DA neurons were spontaneously firing. However, we will report the initial membrane potential on first breaking into the cell for the whole cell recordings in the revision, which did not vary between groups. This is still influenced by action potential activity, but is the timepoint in the recording least impacted by dialyzing of the neuron by the internal solution. We observed increased spontaneous action potential activity ex vivo in slices from CNO-treated mice (Figure 1D), thus at least under these conditions these dopamine neurons are not in depolarization block. We also did not see strong evidence of changes in other intrinsic properties of the neurons with whole cell recordings (e.g. Figure S1C). Overall, our electrophysiology experiments are not consistent with the depolarization block model, at least not due to changes in the intrinsic properties of the neurons. Although our ex vivo findings cannot exclude a contribution of depolarization block in vivo, we do show that CNO-treated mice removed from their cages for open field testing continue to have a strong trend for increased activity for approximately 10 days (S1E). This finding is also consistent with increased activity of the DA neurons. We will add discussion of these important considerations in the revision.

It is great that the authors quantified not only TH levels but also the levels of mCherry, co-expressed with the chemogenetic receptor. This could in principle help to distinguish between TH downregulation and true loss of dopamine neuron cell bodies. However, the approach used here has a major caveat in that the number of mCherry-positive dopamine neurons depends on the proportion of dopamine neurons that were infected and expressed the DREADD and this could very well vary between different mice. It is very unlikely that the virus injection allowed to infect 100% of the neurons in the VTA and SNc. This could for example explain in part the mismatch between the number of VTA dopamine neurons counted in panel 2G when comparing TH and mCherry counts. Also, I see that the mCherry counts were not provided at the 2-week time point. If the mCherry had been expressed genetically by crossing the DAT-Cre mice with a floxed fluorescent reported mice, the interpretation would have been simpler. In this context, I am not convinced of the benefit of the mCherry quantifications. The authors should consider either removing these results from the final manuscript or discussing this important limitation.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment, and we agree that this is a caveat of our mCherry quantification. Quantitation of the number of mCherry+ DA neurons specifically informs the impact on transduced DA neurons, and mCherry appears to be less susceptible to downregulation versus TH. As the reviewer points out, it carries the caveat that there is some variability between injections. Nonetheless, we believe that it conveys useful complementary data. As suggested, we will discuss this caveat in our revision. Note that mCherry was not quantified at the two-week timepoint because there is no loss of TH+ cells at that time.

Although the authors conclude that there is a global decrease in the number of dopamine neurons after 4 weeks of CNO treatment, the post-hoc tests failed to confirm that the decrease in dopamine number was significant in the SNc, the region most relevant to Parkinson's. This could be due to the fact that only a small number of mice were tested. A "n" of just 4 or 5 mice is very small for a stereological counting experiment. As such, this experiment was clearly underpowered at the statistical level. Also, the choice of the image used to illustrate this in panel 2G should be reconsidered: the image suggests that a very large loss of dopamine neurons occurred in the SNc and this is not what the numbers show. A more representative image should be used.

We agree that the stereology experiments were performed on relatively small numbers of animals. Combined with the small effect size, this may have contributed to the post-hoc tests showing a trend of p=0.1 for both the TH and mCherry dopamine cell counts in the SN at 4 weeks. As part of the planned experiments for our revision, we will perform an additional stereologic analysis to further assess the loss of SNc dopamine neurons. We will also review and ensure the images are representative.

In Figure 3, the authors attempt to compare intracellular calcium levels in dopamine neurons using GCaMP6 fluorescence. Because this calcium indicator is not quantitative (unlike ratiometric sensors such as Fura2), it is usually used to quantify relative changes in intracellular calcium. The present use of this probe to compare absolute values is unusual and the validity of this approach is unclear. This limitation needs to be discussed. The authors also need to refer in the text to the difference between panels D and E of this figure. It is surprising that the fluctuations in calcium levels were not quantified. I guess the hypothesis was that there should be more or larger fluctuations in the mice treated with CNO if the CNO treatment led to increased firing. This needs to be clarified.

We thank the reviewer for this comment. We understand that this method of comparing absolute values is unconventional. However, these animals were tested concurrently on the same system, and a clear effect on the absolute baseline was observed. We will include a caveat of this in our discussion. Panel D of this figure shows the raw, uncorrected photometry traces, whereas panel E shows the isosbestic corrected traces for the same recording. In panel E, the traces follow time in ascending order. We will also include frequency and amplitude data for these recordings.

Although the spatial transcriptomic results are intriguing and certainly a great way to start thinking about how the CNO treatment could lead to the loss of dopamine neurons, the presented results, the focusing of some broad classes of differentially expressed genes and on some specific examples, do not really suggest any clear mechanism of neurodegeneration. It would perhaps be useful for the authors to use the obtained data to validate that a state of chronic depolarization was indeed induced by the chronic CNO treatment. Were genes classically linked to increased activity like cfos or bdnf elevated in the SNc or VTA dopamine neurons? In the striatum, the authors report that the levels of DARP32, a gene whose levels are linked to dopamine levels, are unchanged. Does this mean that there were no major changes in dopamine levels in the striatum of these mice?

We will review the expression of activity-related genes in our dataset, although we must keep in mind that these genes may behave differently in the context of chronic activation as opposed to acutely increased activity. We will also include experiments assessing striatal dopamine levels by HPLC in the revision.

The usefulness of comparing the transcriptome of human PD SNc or VTA sections to that of the present mouse model should be better explained. In the human tissues, the transcriptome reflects the state of the tissue many years after extensive loss of dopamine neurons. It is expected that there will be few if any SNc neurons left in such sections. In comparison, the mice after 7 days of CNO treatment do not appear to have lost any dopamine neurons. As such, how can the two extremely different conditions be reasonably compared?

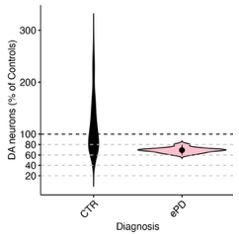

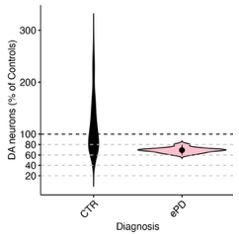

Our mouse model and human PD progress over distinct timescales, as is the case with essentially all mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases. Nonetheless, in our view there is still great value in comparing gene expression changes in mouse models with those in human disease. It seems very likely that the same pathologic processes that drive degeneration early in the disease continue to drive degeneration later in the disease. Note that we have tried to address the discrepancy in time scales in part by comparing to early PD samples when there is more limited SNc DA neuron loss. Please note the numbers of DA neurons within the areas we have selected for sampling (Figure at right). Therefore, we can indeed use spatial transcriptomics to compare dopamine neurons from mice with initial degeneration and patients where degeneration is ongoing during their disease.

Author response image 1.

Violin plot of DA neuron proportions sampled within the vulnerable SNV (deconvoluted RCTD method used in unmasked tissue sections of the SNV). Control and early PD subjects.

Comments on the discussion:

In the discussion, the authors state that their calcium photometry results support a central role of calcium in activity-induced neurodegeneration. This conclusion, although plausible because of the very broad pre-existing literature linking calcium elevation (such as in excitotoxicity) to neuronal loss, should be toned down a bit as no causal relationship was established in the experiments that were carried out in the present study.

Our model utilizes hM3Dq-DREADDs that function by increasing intracellular calcium to increase neuronal excitability, and our results show increased Ca2+ by fiber photometry and changes to Ca2+-related genes, strongly suggesting a causal relation and crucial role of calcium in the mechanism of degeneration. However, we agree that we have not experimentally proven this point, as we acknowledged in the text. Additionally, we have planned revision experiments involving chronic isradipine treatment to further test the role of calcium in the mechanism of degeneration in this model.

In the discussion, the authors discuss some of the parallel changes in gene expression detected in the mouse model and in the human tissues. Because few if any dopamine neurons are expected to remain in the SNc of the human tissues used, this sort of comparison has important conceptual limitations and these need to be clearly addressed.

As discussed, we can sample SN DA neurons in early PD (see figure above), and in our view there is great value for such comparisons. We agree that discussion of appropriate caveats is warranted and this will be clearly addressed in the revision.

A major limitation of the present discussion is that it does not discuss the possibility that the observed phenotypes are caused by the induction of a chronic state of depolarization block by the chronic CNO treatment. I encourage the authors to consider and discuss this hypothesis.

As discussed above, our analyses of DA neuron firing in slices and open field testing to date do not support a prominent contribution of depolarization block with chronic CNO treatment. However, we cannot rule out this hypothesis, therefore we will include additional electrophysiology experiments and add discussion of this important consideration.

Also, the authors need to discuss the fact that previous work was only able to detect an increase in the firing rate of dopamine neurons after more than 95% loss of dopamine neurons. As such, the authors need to clearly discuss the relevance of the present model to PD. Are changes in firing rate a driver of neuronal loss in PD, as the authors try to make the case here, or are such changes only a secondary consequence of extensive neuronal loss (for example because a major loss of dopamine would lead to reduced D2 autoreceptor activation in the remaining neurons, and to reduced autoreceptor-mediated negative feedback on firing). This needs to be discussed.

As discussed above, while increases in dopamine neuron activity may be compensatory after loss of neurons, the precise percentage required to induce such compensatory changes is not defined in mice and varies between paradigms, and the threshold level is not known in humans. We also reiterate that a compensatory increase in activity could still promote the degeneration of critical surviving DA neurons, whose loss underlies the substantial decline in motor function that typically occurs over the course of PD. Moreover, there are also multiple lines of evidence to suggest that changes in activity can initiate and drive dopamine neuron degeneration (Rademacher & Nakamura, Exp Neurol 2024). For example, overexpression of synuclein can increase firing in cultured dopamine neurons (Dagra et al., NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2021, PMID: 34408150) while mice expressing mutant Parkin have higher mean firing rates (Regoni et al., Cell Death Dis 2020, PMID: 33173027). Similarly, an increased firing rate has been reported in the MitoPark mouse model of PD at a time preceding DA neuron degeneration (Good et al., FASEB J 2011, PMID: 21233488). We also acknowledge that alterations to dopamine neuron activity are likely complex in PD, and that dopamine neuron health and function can be impacted not just by simple increases in activity, but also by changes in activity patterns and regularity. We will amend our discussion to include the important caveat of changes in activity occurring as compensation, as well as further evidence of changes in activity preceding dopamine neuron death.

There is a very large, multi-decade literature on calcium elevation and its effects on neuronal loss in many different types of neurons. The authors should discuss their findings in this context and refer to some of this previous work. In a nutshell, the observations of the present manuscript could be summarized by stating that the chronic membrane depolarization induced by the CNO treatment is likely to induce a chronic elevation of intracellular calcium and this is then likely to activate some of the well-known calcium-dependent cell death mechanisms. Whether such cell death is linked in any way to PD is not really demonstrated by the present results. The authors are encouraged to perform a thorough revision of the discussion to address all of these issues, discuss the major limitations of the present model, and refer to the broad pre-existing literature linking membrane depolarization, calcium, and neuronal loss in many neuronal cell types.

While our model demonstrates classic excitotoxic cell death pathways, we would like to emphasize both the chronic nature of our manipulation and the progressive changes observed, with increasing degeneration seen at 1, 2, and 4 weeks of hyperactivity in an axon-first manner. This is a unique aspect of our study, in contrast to much of the previous literature which has focused on shorter timescales. Thus, while we will revise the discussion to more comprehensively acknowledge previous studies of calcium-dependent neuron cell death, we believe we have made several new contributions that are not predicted by existing literature. We have shown that this chronic manipulation is specifically toxic to nigral dopamine neurons, and the data that VTA dopamine neurons continue to be resilient even at 4 weeks is interesting and disease-relevant. We therefore do not want to use findings from other neuron types to draw assumptions about DA neurons, which are a unique and very diverse population. We acknowledge that as with all preclinical models of PD, we cannot draw definitive conclusions about PD with this data. However, we reiterate that we strongly believe that drawing connections to human disease is important, as dopamine neuron activity is very likely altered in PD and a clearer understanding of how dopamine neuron survival is impacted by activity will provide insight into the mechanisms of PD.