Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorLeopoldo PetreanuChampalimaud Center for the Unknown, Lisbon, Portugal

- Senior EditorJohn HuguenardStanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

The manuscript by Tuberosa et al outlines the generation of a new set of transgenic mice that express different recombinases specifically in Smim32 positive cells. They show that Smim32 is a useful marker of the mouse claustrum. Therefore, these mice could be useful for functional studies focused on measuring claustrum activity or manipulating the claustrum using optogenetic and pharmacogenetic tools.

Strengths:

The manuscript provides a new genetic approach to target claustrum neurons, using Smim32. The work may help future studies where claustrum excitatory neurons are measured or manipulated.

Weaknesses:

A toolbox is only useful if others can use it. Therefore, these mice should be made available to the community through commercial vendors. Without this added step, this toolbox and method does not provide any utility to the research community.

The data presented and quantified in each figure subpanel are from N = 1 mouse. This is not acceptable or conventional. Replication is an important aspect of any paper, and currently, there are no replicates contained in the manuscript. Additional examples of female mice should also be included and separately quantified. Mice from different litters should be used for replicates.

Given the preliminary nature of these data from the minimum possible number of mice, a better characterization of all data should be undertaken.

The tone of the paper implies that this is the superior way to locate the claustrum. A more balanced discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of these mice should be included. Several sentences highlighting the shortfalls of other approaches are overstated and should be toned down.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

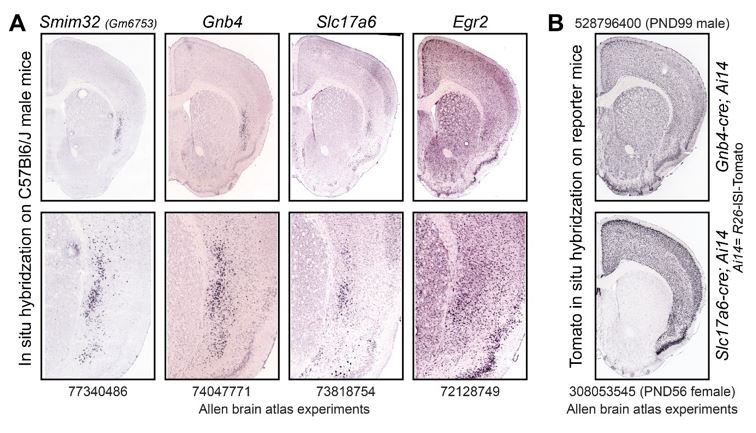

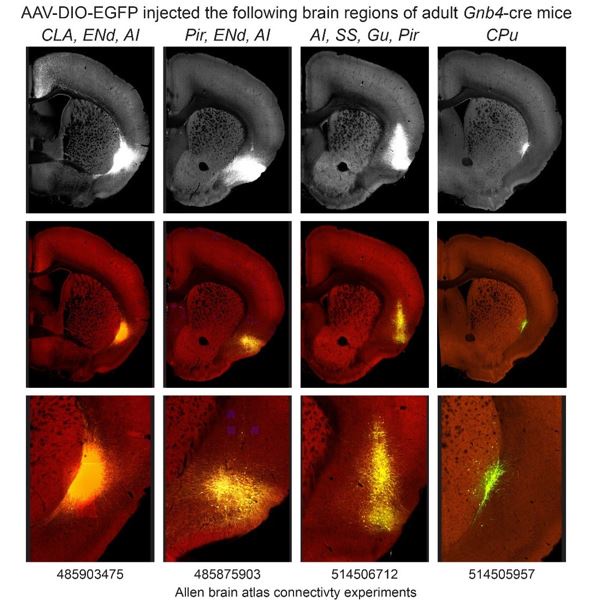

Rodent studies of claustrum are complicated by the tube-like shape of this nucleus. As such, judicious viral strategies alone or in combination with existing Cre driver lines (Egr2, Gnb4, Slc17a6, and Tbx21) represent the current gold standard for claustrum structure and function investigation. Any improvement in tools that would allow better genetic access to the claustrum are always desired, as with any nucleus in brain. This paper describes the expression pattern of the gene Smim32 and characterization of new mouse transgenic lines expressing Cre/Flp recombinase driven by the Smim32 promoter. The authors should be applauded for the work to develop these new tools presented in the study. Overall, the strengths of the paper lie in the development of new mouse lines that are well-characterized in comparison to other molecular markers of the claustrum. Weaknesses lie in poor anatomical definitions of the claustrum (and endopiriform nucleus). Smim32 expression is used to define claustrum anatomical boundaries, rather than first using several structural, molecular, and connectivity lines of evidence to define the claustrum anatomically and then to assess whether Smim32 expression fits within this anatomical definition. Another major weakness is the fact that Cre/Flp expression driven by the Smim32 promoter is present in non-claustrum regions, including the neighboring cortex, striatum, and endopiriform nucleus as well as the more distant thalamic reticular nucleus. Despite this, the conclusion of the study, as communicated by the authors, is that selective interrogation of the claustrum is now possible with these Smim32-based tools. Therefore, the data do not support the claims and conclusions.

Very concerning is problematic language in the abstract and introduction sections that diminish the impact of several published studies (not cited) that have led to important findings regarding claustrum function. The authors Create an argument that all the research performed thus far on the claustrum is unreliable because targeting the structure has been sub-optimal. This is definitely not the case for several studies from multiple labs. If investigators new to the claustrum were to read this paper, they would conclude that all previous data hold little-to-no value and that using these tools set forth the possibility, at long last, to solve claustrum structural and functional queries. Here is an example from the abstract of the problematic language: "However, research on the CLA has been challenging due to difficulties in specifically and comprehensively targeting its neuronal populations. In various cases, this limitation has led to inconsistent findings and a lack of reliable data." (no references cited). Since Smim32 driven recombinase (in 61 or 62lrod) is not exclusively expressed in the claustrum, it is not clear how Smim32 is an advantage over possible Nr4a2 or, the more selective, GNB4 Cre driver lines. Taken together, the goal of the study as articulated in the Introduction: "Our goal was here to generate genetic tools capable of targeting the majority of mouse CLA projection neurons without affecting other brain cell populations, or tissues outside the brain" has not been met and, therefore, the conclusion of the study based on the data "With these genetic tools in hand, the comprehensive targeting and functional probing of the densely connected CLA is now possible" is unfortunately also unmet.

The manuscript does convincingly show that Smim32 targets excitatory neurons in the claustrum as evidenced by exclusive overlap of Smim32 expression with Vglut2 and not GAD (fig 1 and suppl fig 1). Additionally, the manuscript provides sufficient evidence that neurons in the claustrum area expressing Smim32 further co-express a number of other molecular markers of claustrum, including Nr4a2 (fig1), Lxn, Gnb4, and Oprk1 (fig 2), and Slc17a6 (suppl fig 1). The authors further show that Smim32 is not co-expressed with molecular markers of layer VI cortex like Ctgf and Rprm (fig 2). However, by limiting the line of evidence to molecular expression, the study fails to escape the limitations of molecular markers, which cannot by themselves be used to define the anatomical boundary of the claustrum. The expression of several of these markers in the neighboring endopiriform nucleus, including Smim32, is evidence that using molecular markers as a sole indicator of the anatomy of the claustrum is not warranted.

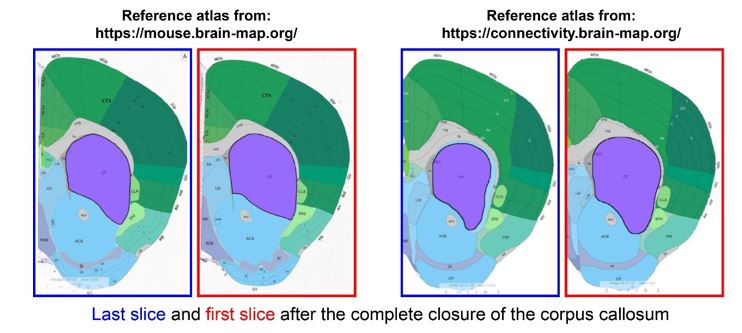

While the anatomical boundaries of the claustrum remain somewhat debated, several standards have emerged to delineate claustrum boundaries. These include immunoreactivity against Gng2 (or PV, especially in rat) to indicate claustrum or against Crym to counter-indicate claustrum. In addition, injection of retrograde tracers into the anterior cingulate cortex or retrosplenial cortex, for example, results in selective targeting of (large) subpopulations of claustrum neurons that help define claustrum location. Further targeting of neurons projecting to the anterior insula or thalamus has been used to delineate the boundaries of what some consider the claustrum shell and others consider the deep layers of the insula. The use of any of these approaches to delineate the claustrum anatomy should be used to describe the spatial distribution of Smim32 and Cre or FlpO in the transgenic lines.

The manuscript provides a description of Smim32 promoter-driven tdTomato in the three transgenic Cre lines during development. This shows strong expression in claustrum and not in surrounding regions. However, as the claustrum borders are not distinct without markers, the anatomical boundary of claustrum for this analysis is deemed arbitrary - an issue that is exacerbated when looking at the developing brain where atlases are less precise and boundaries of the claustrum are ill-defined.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In the manuscript by Tuberosa et al., the authors set out to identify a genetic marker for the claustrum to create transgenic mice as tools to study this challenging brain region. To achieve this, the authors first re-analyzed published scRNAseq datasets from mouse frontal cortex and identified a unique cluster expressing Smim32, which correlated with Nr4a2, a previously reported claustrum marker (though also expressed in layer 6 and elsewhere). Importantly, Smim32 was also found to strongly express in the layer 6 and the thalamic reticular nucleus (with weaker expression in other parts of cortex, striatum, thalamus, olfactory bulb and more). The authors then extensively characterize Smim32 expression relative to a few other genes associated with claustrum and layer 6, as well as creating several novel transgenic mice focused on the Smim32 gene.

Strengths:

The main strength of the paper is the well done scRNAseq analysis, the beautiful ISH images/reconstructions, and the assessment of gene expression throughout development. The main value of this paper is adding the Smim32 gene to the list of markers expressed in the claustrum, though it is not specific to the claustrum, showing extensive expression in TRN and layer 6 of cortex.

Weaknesses:

The main weaknesses are that the results do not support the conclusion, namely that the Smim32 gene is not specific to the claustrum and that no other orthogonal approaches were used to define the claustrum, such as retrograde neuroanatomical tracing from cortex. Also, these results are of limited applicability as the gene expression was only performed in mice, so it is unclear how Smim32 relates to claustrum in other mammalian species (e.g. primates), which have a very clearly defined claustrum. The article is also missing some key literature on the anatomical definition of claustrum, specifically as it relates to the endopiriform nucleus (which is putatively considered part of the claustrum in rodents).