Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

(1) The authors make fairly strong claims that "arousal-related fluctuations are isolated from neurons in the deep layers of the SC" (emphasis added). This conclusion is based on comparisons between a "slow drift axis", a low-dimensional representation of neuronal drift, and other measures of arousal (Figures 2C, 3) and motor output sensitivity (Figures 2B, 3B). However, the metrics used to compare the slow-drift axis and motor activity were computed during separate task epochs: the delay period (600-1100 ms) and a perisaccade epoch (25 ms before and after saccade initiation), respectively. As the authors reference, deep-layer SC neurons are typically active only around the time of a saccade. Therefore, it is not clear if the lack of arousal-related modulations reported for deep-layer SC neurons is because those neurons are truly insensitive to those modulations, or if the modulations were not apparent because they were assessed in an epoch in which the neurons were not active. A potentially more valuable comparison would be to calculate a slow-drift axis aligned to saccade onset.

The reviewer makes an important point that the calculation of an axis can depend critically on the time window of neuronal response. We find when considering this that the slow drift axis is less sensitive to this issue because it is calculated on time-averaged activity over multiple trials. In previous work we found that slow drift calculated on the stimulus evoked response in V4 was very well aligned to slow drift calculated on pre-stimulus spontaneous activity (Cowley et al, Neuron, 2020, Supplemental Figure 3A and 3B). To address this issue in the present data, we compared the axis computed for an example session for neural activity during the delay period and neural activity aligned to saccade onset. As shown new Figure 2 – figure supplement 1 in the revised manuscript, we found a similar lack of arousal-related modulations for deep-layer SC neurons when slow drift was computed using the saccade epoch (25ms before to 25ms after the onset of the saccade). Figure 2 – figure supplement 1A shows loadings for the SC slow drift axis when it was computed using spiking responses during the delay period (as in the main manuscript analysis). In contrast, Figure 2 – figure supplement 1B shows loadings from the same session when the SC slow drift axis was computed using spiking responses during the saccade epoch. The plots are highly similar and in both cases the loadings were weaker for neurons recorded from channels at the bottom of the probe which have a higher motor index. Finally, we found that projections onto the SC slow drift axis for this session were strongly correlated when the slow drift axis was computed using spiking responses during the delay period and the saccade epoch (r = 0.66, p < 0.001, Figure 1C). Taken together, these results suggest that arousal-related modulations are less evident in deep-layer SC neurons irrespective of whether slow drift was computed during the delay or saccade epoch (see also Public Reviews, Reviewer 1, Point 2).

(2) More generally, arousal-related signals may persist throughout multiple different epochs of the task. It would be worthwhile to determine whether similar "slow-drift" dynamics are observed for baseline, sensory-evoked, and saccade-related activity. Although it may not be possible to examine pupil responses during a saccade, there may be systematic relationships between baseline and evoked responses.

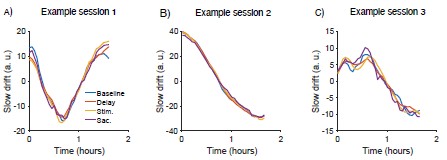

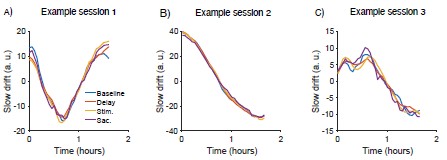

Similar to the point above, slow drift dynamics tend to be similar across different response epochs because they are averaged across many trials and seem to tap into responsivity trends that are robust across epochs. As shown in Author response image 1 below, and the Figure 2 – figure supplement 1 in the revised manuscript, similar dynamics were observed when the SC slow drift axis was computed using spiking responses during the baseline, delay, visual and saccade epochs. We did not investigate differences between baseline and evoked pupil responses in the current paper. However, these effects were characterized in one of our previous papers that focused exclusively on the relationship between slow drift and eye-related metrics (Johnston et al., 2022, Cereb. Cortex, Figure 6). In this previous work, we found a negative correlation between baseline and evoked pupil size. Both variables were significantly correlated with slow drift, the only difference being the sign of the correlation.

Author response image 1.

(A-C) Dynamics of slow drift for three example sessions when the SC slow drift axis was computed using spiking responses during the baseline, delay, visual and saccade epochs. Baseline = 100ms before the onset of the target stimulus; Delay = 600 to 1100ms after the offset of the target stimulus; Stim = 25ms to 125ms after the onset of the target stimulus; Sac = 25ms before to 25ms after the onset of the saccade.

Johnston R, Snyder AC, Khanna SB, Issar D, Smith MA (2022) The eyes reflect an internal cognitive state hidden in the population activity of cortical neurons. Cereb Cortex 32:3331–3346.

(3) The relationships between changes in SC activity and pupil size are quite small (Figures 2C & 5C). Although the distribution across sessions (Figure 2C) is greater than chance, they are nearly 1/4 of the size compared to the PFC-SC axis comparisons. Likewise, the distribution of r2 values relating pupil size and spiking activity directly (Figure 5) is quite low. We remain skeptical that these drifts are truly due to arousal and cannot be accounted for by other factors. For example, does the relationship persist if accounting for a very simple, monotonic (e.g., linear) drift in pupil size and overall firing rate over the course of an individual session?

Firstly, it is important to note that the strength of the relationship between projections onto the SC slow drift axis and pupil size (r2 = 0.06) is within the range reported by Joshi et al. (2016, Neuron, Figure 3). They investigated the median variance explained between the spiking responses of individual SC neurons and pupil size and found it to be approximately 0.02 across sessions. Secondly, our statistical approach of testing the actual distribution of r2 values against a shuffled distribution was specifically designed to rule out the possibility that the relationship between SC spiking responses and pupil size occurred due to linear drifts. The shuffled distribution in Figure 2C of the main manuscript represents the variance that can be explained by one session’s slow drift correlated with another session’s pupil, which would contain effects that occurred due to linear drifts alone. That the actual proportion of variance explained was significantly greater than this distribution suggests that the relationship between projections onto the SC slow drift axis and pupil size reflects changes in arousal rather than other factors related to linear drifts.

Joshi S, Li Y, Kalwani RM, Gold JI (2016) Relationships between Pupil Diameter and Neuronal Activity in the Locus Coeruleus, Colliculi, and Cingulate Cortex. Neuron 89:221–234.

(4) It is not clear how the final analysis (Figure 6) contributes to the authors' conclusions. The authors perform PCA on: (i) residual spiking responses during the delay period binned according to pupil size, and (ii) spiking responses in the saccade epoch binned according to target location (i.e., the saccade tuning curve). The corresponding PCs are the spike-pupil axis and the saccade tuning axis, respectively. Unsurprisingly, the spikepupil axis that captures variance associated with arousal (and removes variance associated with saccade direction) was not correlated with a saccade-tuning axis that captures variance associated with saccade direction and omits arousal. Had these measures been related it would imply a unique association between a neuron's preferred saccade direction and pupil control- which seems unlikely. The separation of these axes thus seems trivial and does not provide evidence of a "mechanism...in the SC to prevent arousal-related signals interfering with the motor output." It remains unknown whether, for example, arousal-related signals may impact trial-by-trial changes in neuronal gain near the time of a saccade, or alter saccade dynamics such as acceleration, precision, and reaction time.

The reviewer makes a good point, and we agree that more evidence is needed to determine if the separation of the pupil size axis and saccade tuning axis is the mechanism through which cognitive and arousal-related signals can be intermixed in the SC. In the revised manuscript (lines 679-682), we have raised this as a possible explanation that necessitates further study rather than stating definitively that it is the exact mechanism through which these signals are kept separate. Our analysis here is similar to the one from Smoulder et al (2024, Neuron, Fig. 2F), in which the interactions between reward signals and target tuning in M1 were examined (and found to be orthogonal). While we agree with the reviewer that it may seem “trivial” for these axes to be orthogonal, it does not have to be so. If, for example, neural tuning curves shifted with changes in pupil size through gain changes that revealed tuning or affected tuning curve shape, there could be projections of the pupil axis onto the target tuning axis. Thus, while we agree with the reviewer that it appears sensible for these two axes to be orthogonal, our result is nonetheless a novel finding. We have edited the text in our revised manuscript, however, to make sure the nuance of this point is conveyed to the reader.

Smoulder AL, Marino PJ, Oby ER, Snyder SE, Miyata H, Pavlovsky NP, Bishop WE, Yu BM, Chase SM, Batista AP. A neural basis of choking under pressure. Neuron. 2024 Oct 23;112(20):3424-33.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

(1) The greatest weakness in the present research is the fact that arousal is a functionally less important non-motoric variable. The authors themselves introduce the problem with a discussion of attention, which is without any doubt the most important cognitive process that needs to be functionally isolated from oculomotor processes. Given this introduction, one cannot help but wonder, why the authors did not design an experiment, in which spatial attention and oculomotor control are differentiated. Absent such an experiment, the authors should spend more time explaining the importance of arousal and how it could interfere with oculomotor behavior.

Although attention does represent an important cognitive process, we did not design an experiment in which attention and oculomotor control are differentiated because attention does not appear to be related to slow drift. In our first paper that reported on this phenomenon, we investigated the effects of spatial attention on slow fluctuations in neural activity by cueing the monkeys to attend to a stimulus in the left or right visual field in a block-wise manner. Each block lasted ~20 minutes and we found that slow drift did not covary with the timing of cued blocks (see Figure 4A, Cowley et al., 2020, Neuron). Furthermore, there is a large body of work showing that arousal also impacts motor behavior leading to changes in a range of eye-related metrics (e.g., pupil size, microsaccade rate and saccadic reaction time - for review, see Di Stasi et al. 2013, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.). We also note that the terms attention and arousal are often used in nonspecific and overlapping ways in the literature, adding to some potential confusion here. Nonetheless, pupil-linked arousal is an important variable that impacts motor performance. This has now been stated clearly in the Introduction of the revised manuscript (lines 108-114) to address the reviewer’s concerns and highlight the importance of studying how precise fixation and eye movements are maintained even in the presence of signals related to ongoing changes in brain state.

Cowley BR, Snyder AC, Acar K, Williamson RC, Yu BM, Smith MA (2020) Slow Drift of Neural Activity as a Signature of Impulsivity in Macaque Visual and Prefrontal Cortex. Neuron 108:551-567.e8.

(2) In this context, it is particularly puzzling that one actually would expect effects of arousal on oculomotor behavior. Specifically, saccade reaction time, accuracy, and speed could be influenced by arousal. The authors should include an analysis of such effects. They should also discuss the absence or presence of such effects and how they affect their other results.

As described above, several studies across species have demonstrated that arousal impacts motor behavior e.g., saccade reaction time, saccade velocity and microsaccade rate (for review, see Di Stasi et al. 2013, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.). This has been clarified in the Introduction of the revised manuscript to address the reviewer's concerns (lines 108-114). Our prior work (Johnston et al, Cerebral Cortex, 2022) shows that slow drift impacts several types of oculomotor behavior. Overall, these studies highlight the impact of arousal on eye movements as a robust effect, and support the present investigation into arousal and oculomotor control signals. While we agree reaction time, accuracy, and speed all can be influenced by arousal depending on task demands, the present study is focused on the connection between slow fluctuations in neural activity, linked to arousal, and different subpopulations of SC neurons.

Di Stasi LL, Catena A, Cañas JJ, Macknik SL, Martinez-Conde S (2013) Saccadic velocity as an arousal index in naturalistic tasks. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37:968–975.

Johnston R, Snyder AC, Khanna SB, Issar D, Smith MA (2022) The eyes reflect an internal cognitive state hidden in the population activity of cortical neurons. Cereb Cortex 32:3331–3346.

(3) The authors use the analysis shown in Figure 6D to argue that across recording sessions the activity components capturing variance in pupil size and saccade tuning are uncorrelated. however, the distribution (green) seems to be non-uniform with a peak at very low and very high correlation specifically. The authors should test if such an interpretation is correct. If yes, where are the low and high correlations respectively? Are there potentially two functional areas in SC?

We agree with the reviewer that our actual data distribution was non-uniform. We examined individual sessions with high and low variance explained and did not find notable differences. One source of this variation has to do with session length. Longer sessions in principle should have a chance distribution of variance explained closer to zero because they contained more time bins. Given that we had no specific hypothesis for a non-uniform distribution, we have simply displayed the full distribution of values in our figure and the statistical result of a comparison to a shuffled distribution.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

(1) However, I am concerned about two main points: First, the authors repeatedly say that the "output" layers of the SC are the ones with the highest motor indices. This might not necessarily be accurate. For example, current thresholds for evoking saccades are lowest in the intermediate layers, and Mohler & Wurtz 1972 suggested that the output of the SC might be in the intermediate layers. Also, even if it were true that the high motor index neurons are the output, they are very few in the authors' data (this is also true in a lot of other labs, where it is less likely to see purely motor neurons in the SC). So, this makes one wonder if the electrode channels were simply too deep and already out of the SC? In other words, it seems important to show distributions of encountered neurons (regardless of the motor index) across depth, in order to better know how to interpret the tails of the distributions in the motor index histogram and in the other panels of Figure Supplement 1. I elaborate more on these points in the detailed comments below.

The reviewer makes a good point about the efferent signals from SC. It is true that electrical thresholds are often lowest in intermediate layers, though deep layers do project to the oculomotor nuclei (Sparks, 1986; Sparks & Hartwich-Young, 1989) and often intermediate and deep layers are considered to function together to control eye movements (Wurtz & Albano, 1980). As suggested by the reviewer, we have edited the text throughout the manuscript to say that slow drift was less evident in SC neurons with a higher motor index, as well as included the above references and points about the intermediate and deep layers (Lines 73-81). Aside from the question of which layers of the SC function as the “motor output”, the reviewer raises a separate and important question – are our deep recordings still in SC. Here, we can say definitively that they are. We removed neurons if they did not exhibit elevated (above baseline) firing rates during the visual or saccade epochs of the MGS task (see Methods section on “Exclusion criteria”). All included neurons possessed a visual, visuomotor or motor response, consistent with the response properties of neurons in the SC. In addition, we found a number of neurons well above the bottom of the probe with strong motor responses and minimal loadings onto the slow drift axis (see Figure 2 – figure supplement 1A), consistent with the reviewer’s comment that intermediate layer neurons are tuned for movement and play a role in saccade production.

Mohler CW, Wurtz RH. Organization of monkey superior colliculus: intermediate layer cells discharging before eye movements. Journal of neurophysiology. 1976 Jul 1;39(4):722-44.

Sparks DL. Translation of sensory signals into commands for control of saccadic eye movements: role of primate superior colliculus. Physiol Rev. 1986 Jan;66(1):118-71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1986.66.1.118. PMID: 3511480.

Sparks DL, Hartwich-Young R. The deep layers of the superior colliculus. Reviews of oculomotor research. 1989 Jan 1;3:213-55.

Wurtz RH, Albano JE. Visual-motor function of the primate superior colliculus. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1980;3:189-226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.03.030180.001201. PMID: 6774653.

(2) Second, the authors find that the SC cells with a low motor index are modulated by pupil diameter. However, this could be completely independent of an "arousal signal". These cells have substantial visual responses. If the pupil diameter changes, then their activity should be influenced since the monkey is watching a luminous display. So, in this regard, the fact that they do not see "an arousal signal" in most motor neurons (through the pupil diameter analyses) is not evidence that the arousal signal is filtered out from the motor neurons. It could simply be that these neurons simply do not get affected by the pupil diameter because they do not have visual sensitivity. So, even with the pupil data, it is still a bit tricky for me to interpret that arousal signals are excluded from the "output layers" of the SC.

The reviewer makes an important point about the SC’s visual responses. Neurons with a low motor index are, conversely, likely to have a stronger visual response index. However, we do not believe that changes in luminance can explain why the correlation between SC spiking response and pupil size is weaker for neurons with a lower motor index. Firstly, the changes in pupil size observed in the current paper and our previous work are slow and occur on a timescale of minutes (Cowley et al., 2020, Neuron) and are correlated with eye movement measures such as reaction time and microsaccade rate (Johnston et al., 2022, Cerebral Cortex). This is in stark contrast to luminance-evoked changes in pupil size that occur on a timescale of less than a second. Secondly, as shown the new Figure 5 – figure supplement 1 in the revised manuscript, very similar results were found when SC spiking responses were correlated with pupil size during the baseline period, when only the fixation point was on the screen. Although the luminance of the small peripheral target stimulus can result in small luminance-evoked changes in pupil size, no changes in luminance occurred during the baseline period which was defined as 100ms before the onset of the target stimulus. In Figure 2 – figure supplement 1 and Author response image 1 above, we show that slow drift is the same whether calculated on the baseline response, delay period, or peri-saccadic epoch. Thus, the measurement of slow drift is insensitive to the precise timing of the selection of both the window for the spiking response and the window for the pupil measurement. If luminance were the explanation for the slow changes in firing observed in visually responsive SC neurons, it would require those neurons to exhibit robust, sustained tuned responses to the small changes in retinal illuminance induced by the relatively small fluctuations in pupil size we observed from minute to minute. We are aware of no reports of such behavior in visually-responsive neurons in SC. We have included these analyses and this reasoning in the revised manuscript on lines 478-495.

Reviewer#1 (Recommendations for the author):

(1) It would be useful to provide line numbers in subsequent manuscripts for reviewers.

Line numbers have been added in the revised version of the manuscript.

(2) Page #6; last sentence: "...even impact processing at the early to mid stages of the visuomotor transformation, without leading to unwanted changes in motor output." I do not believe the authors have provided evidence that arousal levels were not associated with changes in motor output.

As suggested by Reviewer 3 (see Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 2), we have edited the text throughout the manuscript to say that slow drift was less evident in SC neurons with a higher motor index. This sentence in the revised manuscript now reads:

“This provides a potential mechanism through which signals related to cognition and arousal can exist in the SC, and even impact processing at the early to mid stages of the visuomotor transformation, without leading to unwanted changes in SC neurons that are linked to saccade execution.”

(3) Page #8; last paragraph: Although deep-layer SC neurons may not have been obtained during every recording session, a summary of the motor index scores observed along the probe across sessions would be useful to confirm their assumptions.

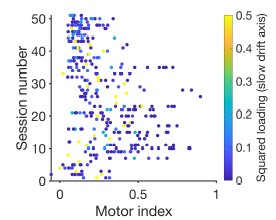

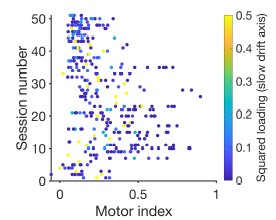

See Author response image 2 below which shows the motor index of each recoded SC neuron on the x-axis and session number on the y-axis. The points are colored by to the squared factor loading which represents the variance explained between the response a neuron and the slow drift axis (see Figure 3B of the main manuscript). You can see from this plot that neurons with a stronger component loading (shown in teal to yellow) typically have a lower motor index whereas the opposite is true for neurons with a weaker component loading (shown in dark blue).

Author response image 2.

Scatter plot showing the motor index of each recorded neuron along with the session number in which it was recorded. The points are colored by to the squared factor loading for each neuron along the slow drift axis. Note that loadings above 0.5 (33 data points in total) have been thresholded at 0.5 so that we could effectively use the color range to show all of the slow drift axis loadings.

(4) Page #10; first paragraph: The authors should state the time window of the delay period used, since it may be distinct from the pupil analysis (first 200ms of delay).

This has been stated in the revised version of the manuscript. The sentence now reads:

“We first asked if arousal-related fluctuations are present in the SC. As in previous studies that recorded from neurons in the cortex (Cowley et al., 2020), we found that the mean spiking responses of individual SC neurons during the delay period (chosen at random on each trial from a uniform distribution spanning 600-1100ms, see Methods) fluctuated over the course of a session while the monkeys performed the MGS task (Figure 2A, left).”

(5) Page #10; second paragraph: Extra period at the end of a sentence: " most variance in the data..".

Fixed in the revised version of the manuscript.

(6) Page #12: "between projections onto the SC slow drift axis and mean pupil size during the first 200ms of the delay period when a task-related pupil response could be observed." What criteria was used to determine whether a task-related pupil response was observed?

This was chosen based on the results of a previous study in our lab that used the same memory-guided saccade task to investigate the relationship between slow drift and changes in based and evoked pupil size (see Johnston et al., 2022, Cereb. Cortex, Figure 6B). The period was chosen based on plotting the average pupil size aligned on different trial epochs. As we show in Figure 5-figure supplement 3 above, the pupil interactions with slow drift did not depend on the particular time window of the pupil we chose.

(7) Page #14; Figure 2A: The axes for the individual channels are strangely floating and quite different from all other figures. Please label the channel in the figure legend that was used as an example of the projected values onto the slow drift axis.

The figure has been changed in the revised version of the manuscript so that the tick mark denoting zero residual spikes per second is on the top layer of each plot. A scale bar was chosen instead of individual axes to reduce clutter in the figure as it was used to demonstrate how slow drift was computed. Residual spiking responses from all neurons were projected on the slow drift axis to generate the scatter plot in the bottom right-hand corner of Figure 2A. There is no single neuron to label.

(8) Page #16: "These results demonstrate that even though arousal-related fluctuations are present in the SC, they are isolated from deep-layer neurons that elicit a strong saccadic response and presumably reside closer to the motor output." In line with our major comments, lack of arousal-related activity during the delay period is meaningless for deep-layer SC neurons that are generally inactive during this time. It does not imply that there is no arousal signal!

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 1, Point 1 & 2. We found a similar lack of arousal-related modulations reported for deep-layer SC neurons when slow drift was computed using the saccade epoch (Figure 1 above). In addition, similar dynamics were observed when the SC slow drift axis was computed using spiking responses during the baseline, delay, visual and saccade period (Figure 2).

(9) Page #18: "These findings provide additional support for the hypothesis that arousalrelated fluctuations are isolated from neurons in the deep layers of the SC." The same criticism from above applies.

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 1, Point 1 & 2.

(10) Page #20; paragraph 3: "Taken together, the findings outlined above..." Would be useful to be more specific when referring to "activity" ; e.g., "...these neurons did not exhibit large fluctuations in delay-period activity over time".

This sentence has been changed in the revised manuscript in light of the reviewer’s comments. It now reads:

“In addition to being more weakly correlated with pupil size, the spiking responses of these neurons did not exhibit large fluctuations over time (Figure 2), and when considering the neuronal population as a whole, explained less variance in the slow drift axis when it was computed using population activity in the SC (Figure 3) and PFC (Figure 4).”

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the author):

The paper is clear and well-written. However, I am concerned about two main points:

(1) First, the authors repeatedly say that the "output" layers of the SC are the ones with the highest motor indices. This might not necessarily be accurate. For example, current thresholds for evoking saccades are lowest in the intermediate layers, and Mohler & Wurtz 1972 suggested that the output of the SC might be in the intermediate layers. Also, even if it were true that the high motor index neurons are the output, they are very few in the authors' data (this is also true in a lot of other labs, where it is less likely to see purely motor neurons in the SC). So, this makes one wonder if the electrode channels were simply too deep and already out of the SC. In other words, it seems important to show distributions of encountered neurons (regardless of motor index) across depth, in order to better know how to interpret the tails of the distributions in the motor index histogram and in the other panels of the figure supplement 1. I elaborate more on these points in the detailed comments below.

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 1.

(2) Second, the authors find that the SC cells with a low motor index are modulated by pupil diameter. However, this could be completely independent of an "arousal signal". These cells have substantial visual responses. If the pupil diameter changes, then their activity should be influenced since the monkey is watching a luminous display. So, in this regard, the fact that they do not see "an arousal signal" in most motor neurons (through the pupil diameter analyses) is not evidence that the arousal signal is filtered out from the motor neurons. It could simply be that these neurons simply do not get affected by the pupil diameter because they do not have visual sensitivity. So, even with the pupil data, it is still a bit tricky for me to interpret that arousal signals are excluded from the "output layers" of the SC.

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 2.

(3) I think that a remedy to the first point above is to change the text to make it a bit more descriptive and less interpretive. For example, just say that the slow drifts were less evident among the neurons with high motor index.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion (see Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 1).

(4) For the second point, I think that it is important to consider the alternative caveat of different amounts of light entering the system. Changes in light level caused by pupil diameter variations can be quite large.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion (see Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 2).

(5) Line 31: I'm a bit underwhelmed by this kind of statement. i.e. we already know that cognitive processes and brain states do alter eye movements, so why is it "critical" that high precision fixation and eye movements are maintained? And, isn't the next sentence already nulling this idea of criticality because it does show that the brain state alters the SC neurons? In fact, cognitive processes are already known to be most prevalent in the intermediate and deep layers of the SC.

It seems clear that while cognitive state does affect eye movements, it is desirable to have some separation between cognitive state and eye movement control. Covert attention, for instance, is precisely a situation where eye movement control is maintained to avoid overt saccades to the attended stimulus, and yet there are clear indications of attention’s impact on microsaccades and fixation. We stand by our statement that an important goal of vision is to have precise fixation and movements of the eye, and yet at the same time the eyes are subject to numerous influences by cognitive state.

(6) Line 65: it is better to clarify that these are "functional layers" because there are actually more anatomical layers.

We have edited this sentence in the revised version of the manuscript so that it now reads:

“The role of these projections in the visuomotor transformation depends on the functional layer of the SC in which they terminate”.

(7) Line 73: this makes it sound like only the deepest layers are topographically organized, which is not true. Also, as early as Mohler & Wurtz, 1972, it was suggested that the intermediate layers have the biggest impacts downstream of the SC. This is also consistent with electrical microstimulation current thresholds for evoking saccades from the SC.

We have addressed the reviewers’ comments about the intermediate layers having the biggest impact downstream of the SC in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 1. Furthermore, line 73 has been changed in the revised manuscript so that it now reads:

“As is the case for neurons in the superficial and intermediate layers, they [SC motor neurons] form a topographically organized map of visual space (White et al. 2017; Robinson 1972; Katnani and Gandhi 2011)”.

(8) Line 100: there is an analogous literature regarding the question of why unwanted muscle contractions do not happen. Specifically, in the context of why SC visual bursts do not automatically cause saccades (which is a similar problem to the ones you mention about cognitive signals interfering by generating unwanted eye movements), both Jagadisan & Gandhi, Curr Bio, 2022 and Baumann et al, PNAS, 2023 also showed that SC population activity not only has different temporal structure (Jagadisan & Gandhi) but also occupy different subspaces (Baumann et al) under these two different conditions (visual burst versus saccade burst). This is conceptually similar to the idea that you are mentioning here with respect to arousal. So, it is worth it to mention these studies here and again in the discussion.

We are grateful to the reviewer for these suggestions and have included text in the Introduction (Lines 125-128) and Discussion (Lines 678-682) of the revised manuscript along with the references cited above.

(9) Line 147: as mentioned above, it is now generally accepted that there are quite a few "pure" motor neurons in the SC. This is consistent with what you find. E.g. Baumann et al., 2023. And, again see Mohler and Wurtz in the 1970's. So, I wonder how useful it is to go too much into this idea of the deeper motor neurons (e.g. the correlations in the other panels of the Figure 1 supplement).

This is related to the reviewer’s comment that the output of the SC might be in the intermediate layers. This concern has been addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 1.

(10) Figure 1 should say where the RF was for the shown spike rasters. i.e. were these the same saccade target across trials? And where was that location relative to the RF? It would help also in the text to say whether the saccade was always to the RF center or whether you were randomizing the target location.

We centered the array of saccade targets using the microstimulation-evoked eye movement for SC (see Methods section “Memory-guided saccade task”) to find the evoked eccentricity, and then used saccade targets with equal spacing of 45 degrees starting at zero (rightward saccade target). We did not do extensive RF mapping beyond this microstimulation centering. In Figure 1, the spike rasters are shown for a target that was visually identified to be within the neuron’s RF based on assessing responses to all 8 target angles. We have added information about this to the figure caption.

(11) Line 218: but were there changes in the eye movement statistics? For example, the slow drift eye movements during fixation? Or even the microsaccades?

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 2, Point 2.

(12) Line 248: shuffling what exactly? I think that more explanation would be needed here.

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 1, Point 3.

(13) Line 263: but isn't this reflecting a sensory transient in the pupil diameter, since the target just disappeared?

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 2.

(14) Line 271: I suspect that slow drift eye movements (in between microsaccades) would show higher correlations. Not sure how well you can analyze those with a video-based eye tracker.

We agree that fixational drift would be a worthwhile metric, but it is not one we have focused on here and to our knowledge does require higher precision tracking.

(15) Line 286: again, see above about similar demonstrations with respect to the visual and motor burst intervals, which clearly cause the same problem (even stronger) as the one studied here.

See reply, including Figure 2.

(16) Line 330: again, I'm not sure deeper necessarily automatically means closer to the output. For example, current thresholds for evoked saccades grow higher as you go deeper. Maybe the authors can ask their colleague Neeraj Gandhi about this point specifically, just to be safe. Maybe the safest would be to remain descriptive about the data, and just say something like: arousal-related fluctuations were absent in our deepest recorded sites.

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 1.

(17) Line 332: likewise, statements like this one here would be qualified if the output was the intermediate layers......anyway if I understand what I read so far in the paper, the signal will be anyway orthogonal to the motor burst population subspace. So, maybe there's no need to emphasize that it goes away in the very deepest layers.

See reply above, Public Reviews, Reviewer 1, Point 4.

(18) Figure 3A: related to the above, I think one issue could be that the deeper contacts might already be out of the SC. Maybe some cell count distribution from each channel should help in this regard. i.e. were you finding way fewer saccade-related neurons in the deepest channels (even though the few that you found were with high motor index)? If so, then wouldn't this just mean that the channel was too deep? I think there needs to be an analysis like this, to convince readers that the channels were still in the SC. Ideally, electrical stimulation current thresholds for evoking saccades at different depths would be tested, but I understand that this can be difficult at this stage.

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 1.

(19) I keep repeating this because in general, cognitive effects are stronger in the intermediate/deeper layers than in the superficial layers. If these interfere with eye movements like arousal, then why should arousal be different?

Few studies have investigated the effects of attention on “pure” movement SC neurons that only discharge during a saccade. One study, which we cited in Introduction (Ignashchenkova et al., 2004, Nat. Neurosci.), found significant differences in spiking responses between trials with and without attentional cueing for visual and visuomotor neurons. No significant difference was found for motor neurons, consistent with our hypothesis that signals related to cognition and arousal are kept separate from saccade-related signals in the SC.

(20) The problem with Figure 5 and its related text is that the neurons with low motor index are additionally visual. So, of course, they can be modulated if the pupil diameter changes!

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 2.

(21) I had a hard time understanding Figure 6.

See reply above, Public Reviews, Reviewer 1, Point 4.

(22) Line 586: these cells have more visual responses and will be affected by the amount of light entering the eye.

Addressed in Public Reviews, Reviewer 3, Point 2.