PEBP1 amplifies mitochondrial dysfunction-induced integrated stress response

Figures

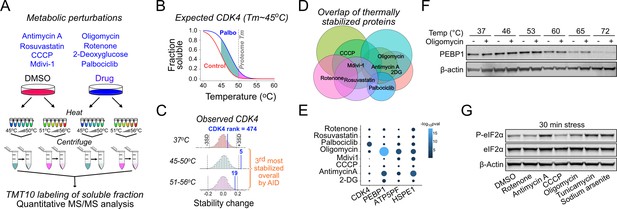

Metabolic perturbation-induced protein state changes identify PEBP1.

(A) Schematic of thermal proteome profiling approach. Eight different drugs, including CDK4/6 inhibitor as the positive control, were used to target metabolism in 143B cells. After heating the samples at 12 different temperatures, temperatures below and above the global proteome melting temperature (50°C) were pooled, heat-denatured proteins removed my centrifugation and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Unheated (37°C) samples and DMSO solvent control were included. (B) Schematic showing the expected thermal denaturation curves for control and palbociclib-treated cells. The green and pink area between the curves shows the integral of the thermal shift detected as difference in CDK4 protein levels in the lower and higher temperature pool. (C) Histograms showing the observed CDK4 ranking in palbociclib-treated cells in the pools heated at different temperature ranges. The overall ranking was obtained using the analysis of independent differences (AID) multivariate analysis. (D) Venn diagram showing the overlap between thermally stabilized proteins with different drugs. A 5% false discovery rate was used to identify the hits. (E) Specificity of protein state alterations illustrated as AID scores (-log10pval) across different drug treatments for selected hits. Note the similarity between oligomycin and antimycin A treatments. (F) Validation of PEBP1 thermal stabilization by oligomycin. Western blot is representative from at least three experiments. (G) Integrated stress response induction after a 30 min treatment with 1 µM rotenone, antimycin A, CCCP, or oligomycin as well as 5 µM tunicamycin or 25 µM sodium arsenite.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig1-data1-v1.zip

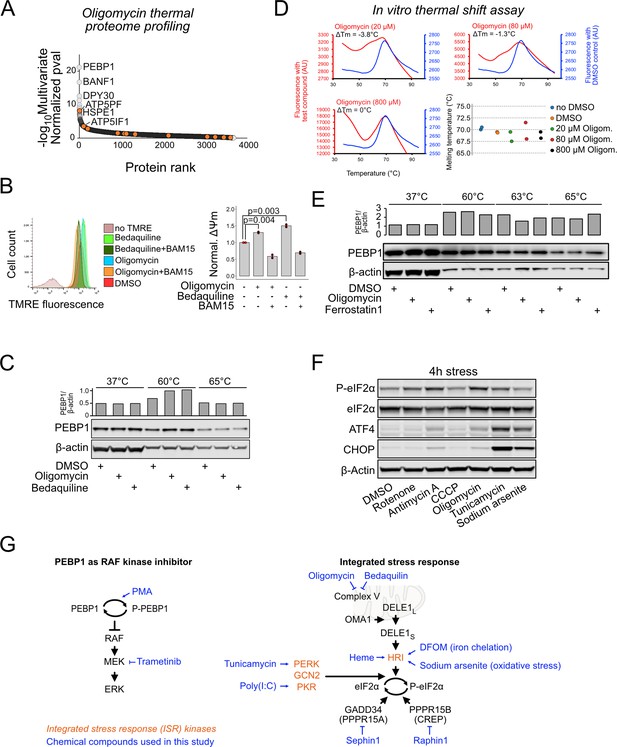

Further characterization of PEBP1 thermal stability in cells and using purified protein.

(A) Ranking of oligomycin-induced protein state changes based on the analysis of independent differences (AID) score. Mitochondrial ATP synthase subunits are indicated with orange. (B) Effect of ATP synthase inhibitors oligomycin and bedaquiline on mitochondrial membrane potential measured as tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) fluorescence. 1 µM oligomycin and 5 µM bedaquiline were used. For uncoupling, 0.5 µM BAM15 was used. Right panel: Quantification of the flow cytometry data for mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) normalized to DMSO control. Data shown in mean ± SD, n=3. ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (C) Thermal shift assay using oligomycin and bedaquiline in 143B cells. (D) In vitro thermal shift assay with 1 µM purified recombinant PEBP1. Representative melting curves for DMSO control (blue) and the indicated concentrations of oligomycin are shown together with the ΔTm between DMSO and drug-treated sample from three technical replicates. The dot chart displays ΔTm from two different experiments. Note the increased fluorescence with higher oligomycin concentration, which may complicate the interpretation of this data. (E) Lysate cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) of PEBP1 treated with 10 µM oligomycin and 10 µM ferrostatin1. (F) Integrated stress response (ISR) induction after a 4 hr treatment with the same drugs as in Figure 1G. (G) Schematic for chemical inhibition and activation of either PEBP1 function as RAF kinase inhibitor (left) or the ISR (right). The various compounds used throughout the manuscript are shown in blue with arrows indicating activation and bars inhibition. The four ISR kinases are indicated in orange.

-

Figure 1—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 1—figure supplement 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig1-figsupp1-data1-v1.zip

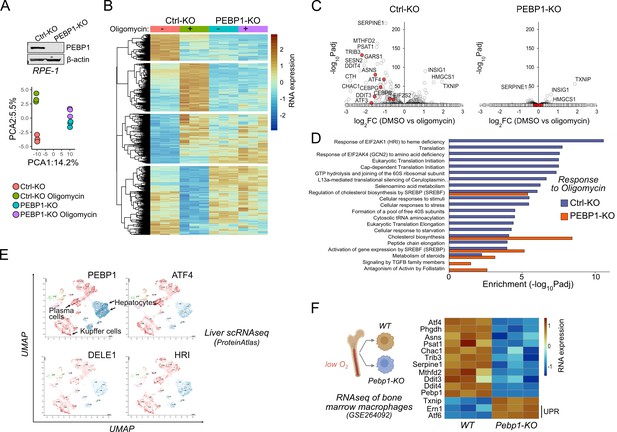

Loss of PEBP1 attenuates integrated stress response (ISR) gene expression.

(A) PEBP1 expression in control and PEBP1 knockout (KO) cells as well as principal component analysis of RNAseq samples treated with and without 1 μm oligomycin for 6 hr. Three replicates were used for each group. (B) Heatmap of significantly changing genes in RNAseq. (C) Comparison of oligomycin-induced gene expression effects using volcano plots of Ctrl and PEBP1 KO cells. ISR genes are highlighted in red. (D) Gene ontology analysis of oligomycin-induced responses in control KO cells (blue) and PEBP1 KO cell (red). (E) Comparison of PEBP1 and mitochondrial ISR signaling component (ATF4, DELE1, HRI) expression in single-cell RNAseq from liver based on publicly available UMAP analysis from ProteinAtlas. For the names of the cell types in other clusters, see here. (F) ISR gene expression from public RNAseq data of bone marrow macrophages isolated from WT and Pebp1 KO mice. Two unfolded protein response (UPR) genes Ern1 and Atf6 are also shown. HRI, heme-regulated inhibitor kinase.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 2A.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig2-data1-v1.zip

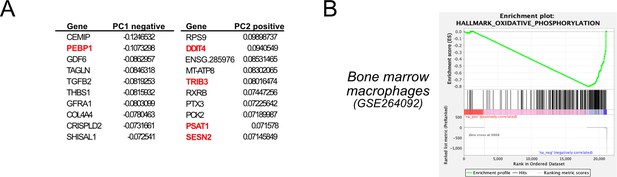

Integrated stress response (ISR) induction in control and PEBP1 knockout (KO) cells by RNAseq.

(A) Top principal component analysis (PCA) loadings showing the individual genes with largest influence on PCA1 and PCA2 dimensions in RPE1 PEBP1 KO cell data treated with oligomycin. PEBP1 and known ISR genes are highlighted in red. (B) Enrichment of oxidative phosphorylation genes by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in bone marrow macrophage RNAseq data.

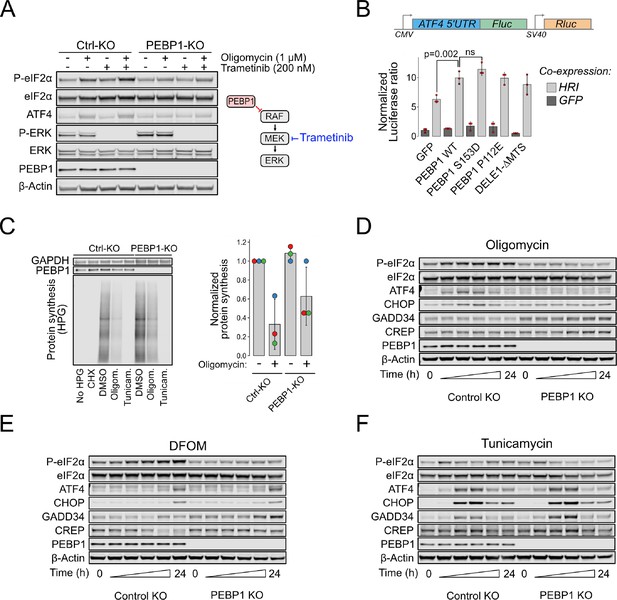

Loss of PEBP1 attenuates heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI)-mediated mitochondrial signaling but not PERK-mediated ER stress.

(A) Western blot analysis of integrated stress response (ISR) activation in RPE1 control and PEBP1 knockout (KO) cells treated with and without MEK inhibitor trametinib. (B) ATF4 luciferase reporter assay in PEBP1 KO cells. Cells were transfected with the dual luciferase reporter (upper panel) in the presence or absence of the indicated genes (either co-expressing with GFP or HRI). Data shown in mean ± SD, n=3. Statistical analysis by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (C) Effect of PEBP1 on protein synthesis assayed by incorporation of a methionine analog, L-homopropargylglycine (HPG), followed by a Click-reaction with fluorescent Azide-647. Cells were treated with 1 µM cycloheximide (CHX), 5 µM oligomycin, or 5 µM tunicamycin to inhibit protein synthesis. Right panel shows quantification of oligomycin effect from three biological replicates (individual experiments highlighted with dot color). (D) Time-course analysis of ISR activation in RPE1 control and PEBP1 KO cells treated with 1 µM oligomycin. (E) Time-course of cells treated with 1 mM deferoxamine mesylate (DFOM). (F) Time-course of cells treated with 1 µM tunicamycin. The specific time points in panels D–F are 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hr. Western blots are representative examples from two to three experiments.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 3.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig3-data1-v1.zip

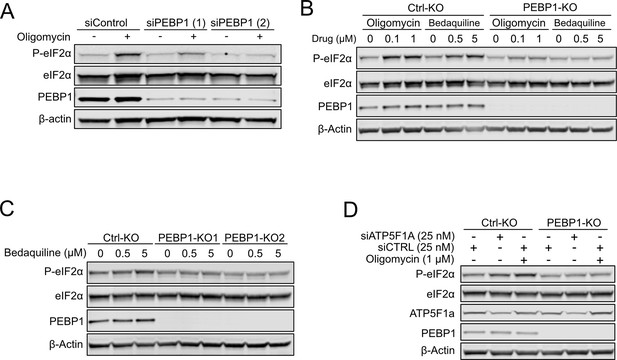

Integrated stress response (ISR) induction in control and PEBP1 knockout (KO) cells is independent of the stress inducer.

(A) Western blot (WB) analysis of cells treated with control and two different PEBP1 siRNA in RPE1 cells. (B) WB analysis of control and PEBP1 KO cells treated with oligomycin and bedaquiline at the concentrations indicated. (C) WB analysis of bedaquiline-induced eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) phosphorylation using KO cell lines generated with two independent sgRNAs. (D) WB analysis of eIF2α phosphorylation in response to ATP synthase subunit ATP5F1A knockdown.

-

Figure 3—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 3—figure supplement 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig3-figsupp1-data1-v1.zip

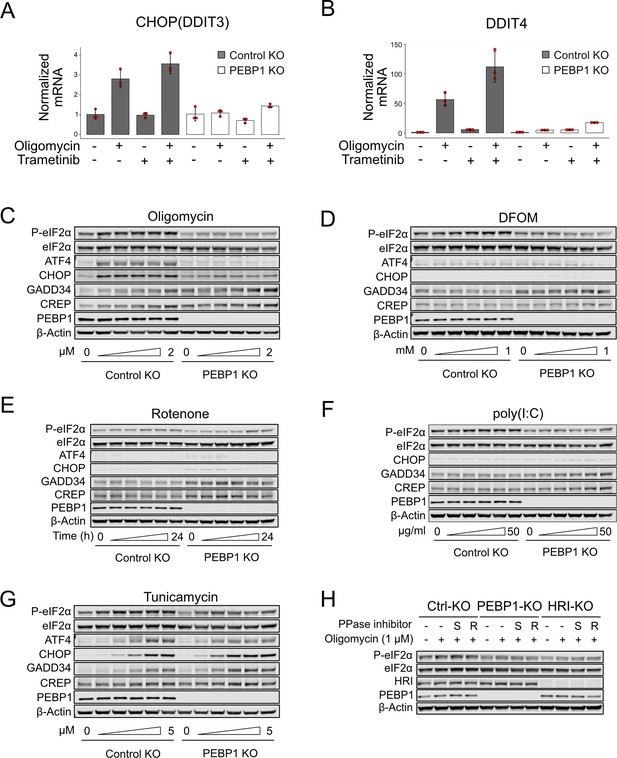

Characterization of PEBP1-mediated integrated stress response (ISR).

(A) CHOP/DDIT3 expression by qPCR in trametinib-treated control and PEBP1 knockout (KO) cells. (B) DDIT4 expression by qPCR in trametinib-treated control and PEBP1 KO cells. Data shown for panels C and D are mean ± SD, n=3. (C) Dose-dependent activation of ISR by oligomycin (0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 µM final conc.) in RPE1 control and PEBP1 KO cells. (D) Dose-dependent activation of ISR by the iron chelator deferoxamine mesylate (DFOM) (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mM final conc). (E) Time-course (0, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hr) of cells treated with 0.5 µM rotenone. (F) Dose-dependent induction of ISR with poly(I:C) for 4 hr. The specific concentrations used were 0, 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 µg/ml. (G) Dose-dependent activation of ISR with tunicamycin (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 µM final conc.) for 4 hr. (H) Effect of 20 µM Sephin-1 (S) and 10 µM Raphin-1 (R) phosphatase inhibitors on oligomycin-induced eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) phosphorylation in control, PEBP1, and heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) KO cells. Phosphatase inhibitors were added 1 hr before adding 1 µM oligomycin, and ISR was induced for 4 hr before cell lysis. All experiments were repeated two to three times with representative data shown.

-

Figure 3—figure supplement 2—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 3—figure supplement 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig3-figsupp2-data1-v1.zip

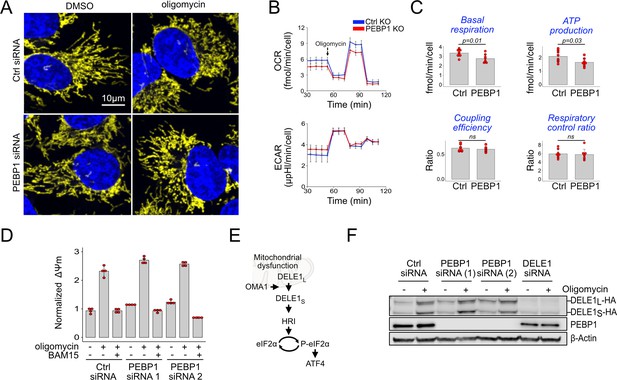

PEBP1 does not interfere with mitochondrial OMA1-DELE1 signaling.

(A) A representative example of mitochondrial fragmentation in 143B cells treated with or without PEBP1 siRNA and 1 µM oligomycin. Mitochondria are shown in yellow, DNA in blue. (B) Seahorse oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) analysis in RPE1 knockout (KO) cells. (C) Quantification of the respiratory parameters from the Seahorse analysis. Data shown in B and C is mean ± SD, n=7. The p-value is from a two-sided t test. (D) Mitochondrial membrane potential after treating control and PEBP1 silenced 143B cells with 1 µM oligomycin or oligomycin with 0.5 µM uncoupler BAM15. (E) Schematic of mitochondrial stress signal transduction. (F) Activation of DELE1-HA in 143B endogenous knock-in cells treated with PEBP1 and DELE1 siRNAs. The long uncleaved form (DELE1L-HA) and the proteolytically processed short form (DELE1S-HA) are indicated.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 4.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig4-data1-v1.zip

Phosphorylation modulates interaction of PEBP1 with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α).

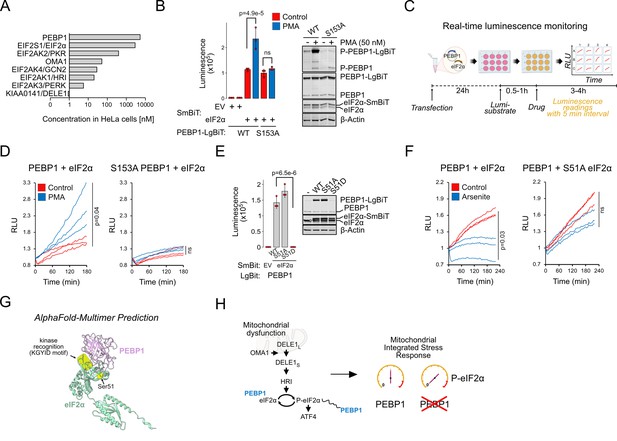

(A) Protein concentrations for PEBP1 and integrated stress response (ISR) components in HeLa cells based on Itzhak et al., 2016. Note the log10 scale. (B) Nanobit interaction assay for PEBP1 and eIF2α in 293T cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated constructs; after 24 hr, cells were treated with and without 50 nM PMA for 4 hr before adding luciferase substrate. Right panel shows the expression levels in cells transfected with WT and S153A PEBP1-LgBiT. Data is representative of three independent biological experiments. (C) Schematic of the real-time interaction monitoring. (D) Real-time analysis of PEBP1 phosphorylation-dependent interaction with eIF2α using WT and S153A PEBP1. Cells were treated with 50 nM PMA. The red and blue traces show data from individual wells, n=3. (E) Effect of eIF2α-S51 mutations on PEBP1-eIF2α interaction. Western blot (WB) (right) shows expression of endogenous and exogenous eIF2α and PEBP1 levels. (F) Real-time analysis of PEBP1 interaction with WT and S51A eIF2α. Cells were treated with 25 µM sodium arsenite. Data is representative of three independent biological experiments with three replicate wells in each experiment. (G) AlphaFold prediction of the putative complex structure between PEBP1 and eIF2α. The KGYID kinase recognition motif and eIF2α-Ser51 location are indicated. (G) Schematic of PEBP1 in mediating mitochondrial ISR amplification. For panels B and E, data shown is mean ± SD, n=3. Statistical analysis by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. For panels D and F, area under curves were calculated and significance tested with two-sided t test.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 5.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig5-data1-v1.zip

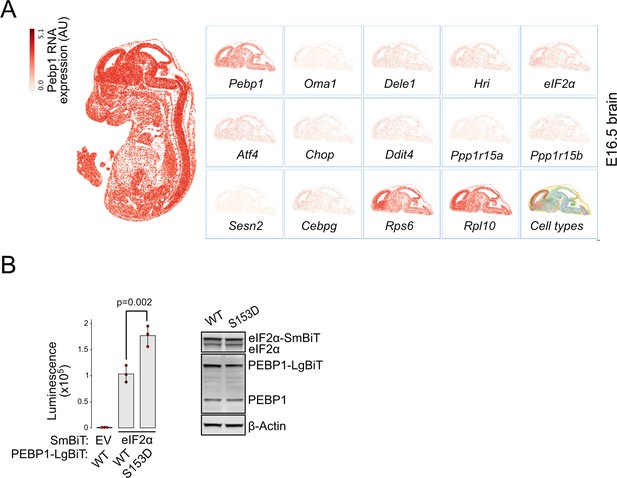

PEBP1 and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) expression and interaction.

(A) Expression of Pebp1, integrated stress response (ISR) components, and the two ribosomal subunits (Rps6. Rpl10) mRNAs in the mouse brain (E16.5) based on Chen et al., 2022. (B) Nanobit interaction assay for PEBP1 and eIF2α in 293T cells. Cells were transfected with the indicated constructs. Luminescence was measured after 24 hr. Right panel shows the expression levels in cells transfected with WT and S153D PEBP1-LgBiT. Data shown is mean ± SD, n=3. Statistical analysis by ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

-

Figure 5—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Original files for western blot analysis displayed in Figure 5—figure supplement 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-fig5-figsupp1-data1-v1.zip

Additional files

-

MDAR checklist

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-mdarchecklist1-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 1

Proteomics data for the small molecules used for the MS-CETSA experiments.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/102852/elife-102852-supp1-v1.xlsx