Differentiation alters stem cell nuclear architecture, mechanics, and mechano-sensitivity

Figures

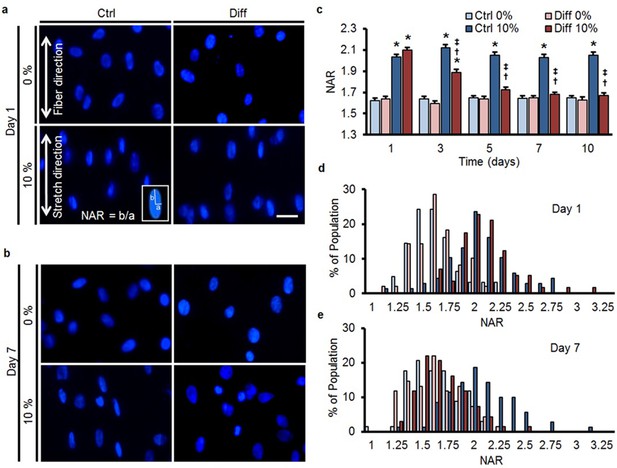

MSC differentiation reduces nuclear deformation with applied stretch.

(a) On day 1, bovine MSCs on aligned nanofibrous scaffolds have elongated nuclei that are oriented in the prevailing fiber direction in both Ctrl and Diff conditions. Application of 10% scaffold stretch increased nuclear deformation under both culture conditions (bottom panels). (b) By day 7, application of 10% stretch continued to increase nuclear deformation in Ctrl conditions, while in Diff conditions nuclear deformation was almost completely absent. Scale: 20 µm. (c) Quantification of nuclear morphology showed that 10% stretch significantly increased MSC nuclear aspect ratio (NAR) in Ctrl conditions, irrespective of culture duration. Conversely, for MSCs in Diff conditions, a progressive decrease in the change in NAR with 10% stretch was observed with increasing culture duration (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. 0%, †p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, ‡p<0.05 vs. day 1, n = 102 nuclei per time point from 4–5 scaffolds per condition, absolute NAR values, mean ± SEM, experiments were carried out at least three times in full). Population distribution of MSC NAR in Ctrl and Diff conditions on day 1 (d) and day 7 (e); on day 1, 10% stretch shifted the distribution to the right for both conditions, while the shift was only apparent in Ctrl conditions on day 7. See Figure 1—source data 1.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Changes in nuclear aspect ratio and population distribution with stretch.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.003

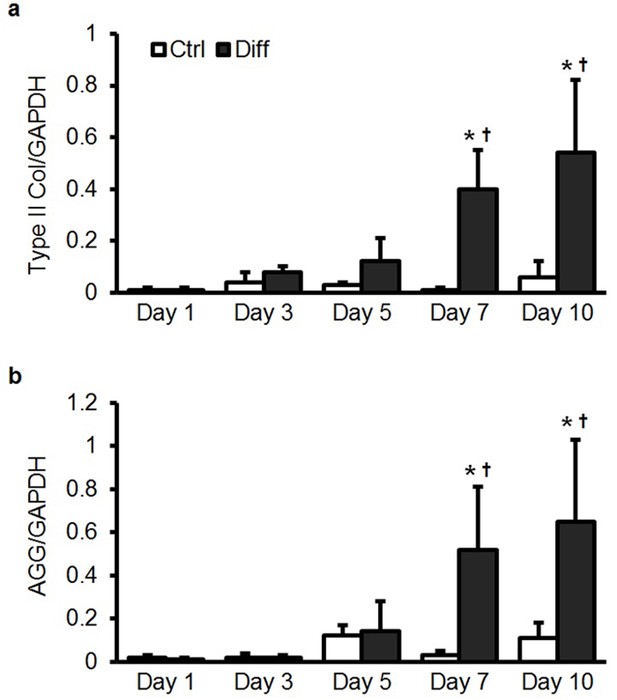

Type II collagen and aggrecan gene expression in bovine MSCs as a function of media condition and time.

(a) Type II collagen (Type II Col) and (b) aggrecan (AGG) gene expression in bovine MSCs as a function of media condition and time when cultured on aligned nanofibrous scaffolds. Culture in differentiation media (Diff) led to a significant increase in fibrochondrogenic markers with culture duration (normalized to GAPDH, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Day 1, n = 5, mean ± SD).

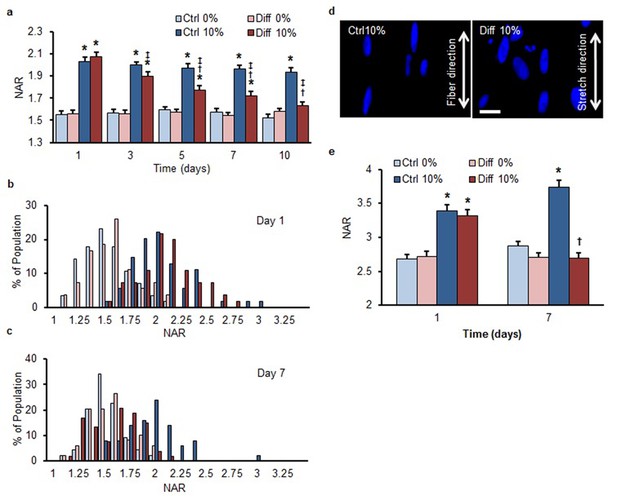

Differentiation-mediated reduction in strain transfer to the nucleus in human bone-marrow-derived MSCs and a human ES-cell line.

The overall response of human MSCs mirrored that of bovine MSCs, indicating that the reduction in nuclear strain transfer is independent of species. (a) Application of 10% scaffold stretch significantly increased NAR in MSCs under both media conditions on day 1. On day 7, nuclei in Ctrl condition continued to increase in NAR with stretch, while those in Diff conditions showed a progressive decrease in the change in NAR as differentiation progressed (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. 0%, †p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, ‡p<0.05 vs. day 1, n = 50 nuclei per time point from 4–5 scaffolds per condition, mean ± SEM). Population distribution of human MSC NAR in Ctrl and Diff conditions on day 1 (b) and day 7 (c). On day 1, 10% scaffold stretch shifted the distribution to the right for both media conditions, while the shift was only apparent in Diff conditions on day 7, consistent with results using bovine MSCs. Nuclear deformation was attenuated in a human ES-cell line cultured under differentiating conditions on aligned nanofibrous scaffolds subjected to 10% stretch. (d) Deformed ES-cell nuclei on scaffolds subjected to 10% stretch. Scale: 20 µm. Note the highly elongated morphology, as evidenced by the NAR > 3, of these nuclei relative to marrow derived MSCs cultured similarly. (e) Application of 10% scaffold stretch significantly increased NAR in ES cells under both media conditions on day 1. On day 7, nuclei in Ctrl conditions continued to increase in NAR, while those in Diff conditions showed a progressive decrease in the change in NAR as differentiation progressed (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. 0%, †p < 0.05 vs. Day 1, n = 100 nuclei per time point from 4–5 scaffolds per condition, mean ± SEM).

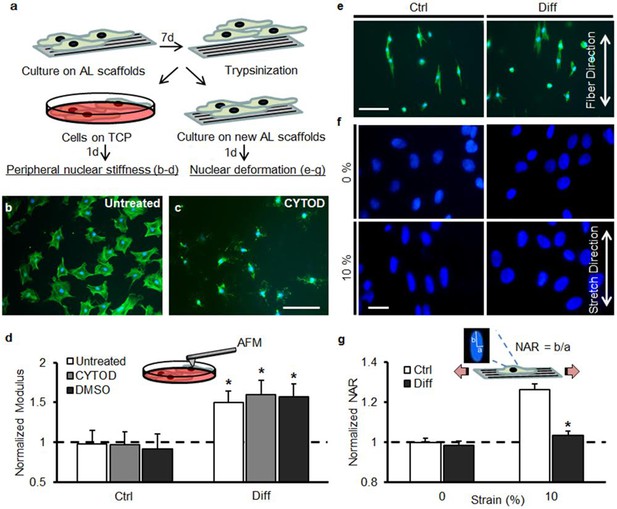

Decreased strain transfer to the nucleus with differentiation is a consequence of nuclear stiffening and not extracellular matrix deposition.

(a) Schematic illustrating how MSCs were cultured on aligned (AL) scaffolds in Ctrl condition or Diff condition for 7 days followed by re-seeding on fresh scaffolds (for stretch studies) or re-plating on tissue culture plastic (TCP, for analysis of peri-nuclear stiffness by AFM). (b) Fluorescent staining of F-actin (green) in MSCs re-plated on TCP for one day and (c) disruption of F-actin via treatment with cytochalasin D (CYTOD) for 30 min. Scale: 100 µm. (d) The peri-nuclear stiffness of differentiated Diff/MSCs was significantly higher than that of undifferentiated Ctrl/MSCs after re-plating on day 7 (normalized to Ctrl values, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, n = 10 per condition, dashed line indicates peri-nuclear modulus on day 1, mean ± SD, experiments were carried out in duplicate). Treatment with CYTOD (or DMSO vehicle control) did not alter the measured peri-nuclear stiffness. (e) F-actin (green) and DAPI (blue) staining of MSCs re-seeded onto fresh scaffolds. Scale: 100 µm. (f) DAPI staining of nuclear morphology before (0%) and after (10%) scaffold stretch showed that differentiated MSC nuclei did not deform after transfer to a fresh scaffold. Scale: 20 µm. (g) Quantification of NAR confirmed lack of deformation of Diff nuclei (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs Ctrl/10% after re-seeding, n = 50 nuclei/condition, mean ± SEM, experiments were carried out at least three times). See Figure 2—source data 1.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Peri-nuclear stiffness measurements and changes in nuclear aspect ratio with stretch.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.007

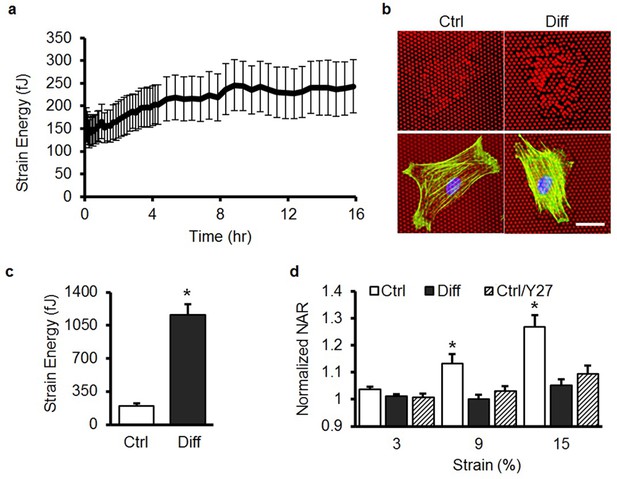

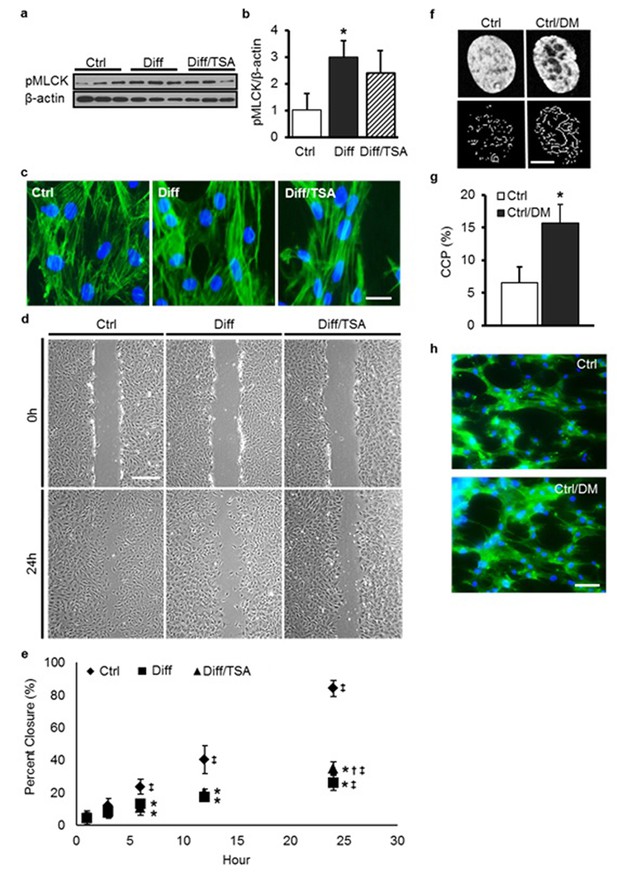

Contractility increases in differentiated MSCs and is necessary for strain transfer to the nucleus.

(a) Traction force increases substantially over the first 16 hr of exposure to 10 ng/ml TGF-β3 (n = 20, Mean ± SD), where time t = 0 shows the baseline response in the absence of TGF-β3. (b) Micro-Post Array Detector (mPAD) analysis showed little post deflection by MSCs in Ctrl conditions, while MSCs cultured in Diff conditions for 7 days showed significant post deflections (bar = 30 μm, F-actin: green; nuclei: blue) and quantification (c) showed that strain energy per cell was higher in MSCs in Diff conditions compared to MSCs in Ctrl conditions (Student’s t-test, *p<0.0001 vs. Ctrl, n = 20/condition, Mean ± SEM). When aligned scaffolds were subjected to stretch (d), nuclear deformation was significantly reduced with either 7 days of differentiation (Diff) or via blockade of contractility in undifferentiated MSCs by ROCK inhibition (Ctrl/Y27, Y27632, 10 μM, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Diff and Ctrl/Y27, n =~ 50/condition, mean ± SEM).

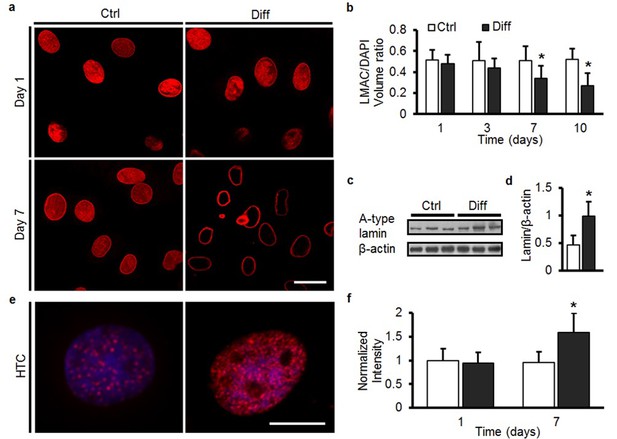

MSC differentiation results in marked nuclear reorganization.

(a) On day 1, Lamin A/C (LMAC) was spread diffusely throughout the nucleus in both Ctrl and Diff conditions. By day 7, Diff conditions resulted in a restriction of LMAC to the nuclear periphery (scale: 20 µm). (b) Quantification showed that the nuclear volume occupancy ratio of LMAC (relative to DAPI) did not change in Ctrl conditions, while this ratio decreased significantly in Diff conditions as a function of culture duration (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, n = 31, mean ± SD, experiments wer carried out in triplicate). (c) Protein levels of A-type lamin (and β-actin) under Ctrl and Diff conditions. (d) Quantification showed a significant increase in A-type lamin with differentiation (Student’s t-test, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, n = 6 from two biological replicates, mean ± SD). (e) Staining for heterochromatin (HTC) in Ctrl and Diff conditions on day 7. Scale: 5 µm. (f) HTC staining intensity in Diff conditions was significantly higher than in Ctrl conditions on day 7 (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, n = 25 nuclei/condition, mean ± SD, experiments were carried out at least three times). See Figure 3—source data 1.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

The nuclear volume occupancy ratio of LMAC, protein levels of A-type lamin and β-actin, and HTC staining intensity.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.010

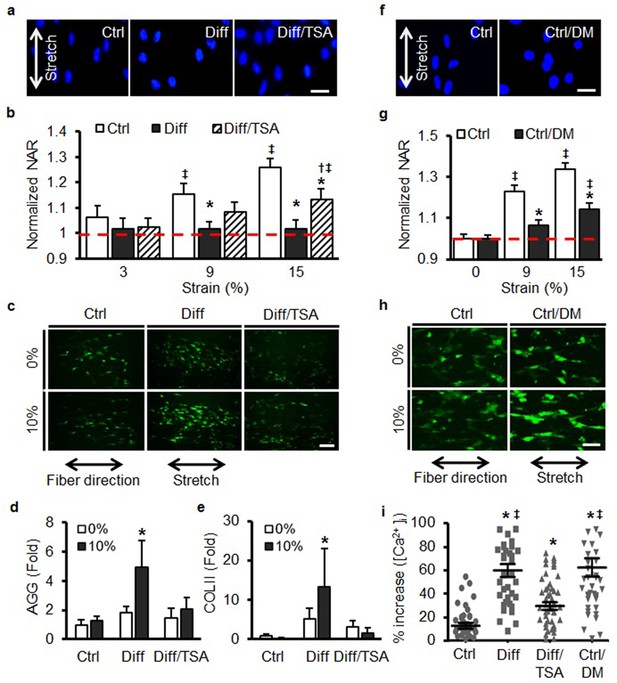

Increases in nuclear mechanics heighten mechanosensitivity of mesenchymal stem cells.

(a) On day 7, 10% static stretch increased nuclear deformation in Ctrl conditions but did not alter nuclear shape under Diff conditions. With TSA treatment (Diff/TSA), nuclear elongation of differentiated MSCs was once again apparent with stretch. Scale: 20 µm (b) Quantification of NAR via tracking of individual nuclei. With TSA treatment of differentiated MSCs, nuclear deformation was once again observed with 15% stretch (normalized to Ctrl 0%, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, ‡p < 0.05 vs. Ctrl 0%, dashed line indicates Ctrl 0%, n = 28, mean ± SEM, experiments were carried out in triplicate). (c and i) Baseline intracellular Ca2+ in MSCs was not different between groups. With 10% stretch, intracellular Ca2+ showed slight increases in Ctrl conditions, and a much more marked increase in Diff conditions. TSA addition (Diff/TSA) reduced intracellular Ca2+ release with stretch (Scale: 100 µm). (d) AGG and (e) COL II levels did not increase with stretch in Ctrl conditions, while significant increases were observed in Diff conditions. Addition of TSA (Diff/TSA), abrogated this stretch-induced response (10% static stretch for 1 hr, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, n = 3, mean ± SD, experiments were carried out in triplicate). (f and g) Pre-treatment of MSCs with D-mannitol (Ctrl/DM) decreased nuclear deformation with stretch (Scale: 20 µm, normalized to ctrl/0%, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, ‡p < 0.05 vs. Ctrl/0%, n = 40, dashed line indicates Ctrl 0%, mean ± SEM, experiments were carried out in triplicate). (h and i) Pre-treatment with D-mannitol (Ctrl/DM) increased intracellular calcium mobilization with stretch compared to Ctrl conditions (Scale: 50 µm, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, ‡p < 0.05 vs. Diff/TSA, n = 50, mean ± SEM, experiments were carried out in triplicate). See Figure 4—source data 1.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Changes in nuclear aspect ratio and type II collagen and aggrecan gene expression with stretch.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.014

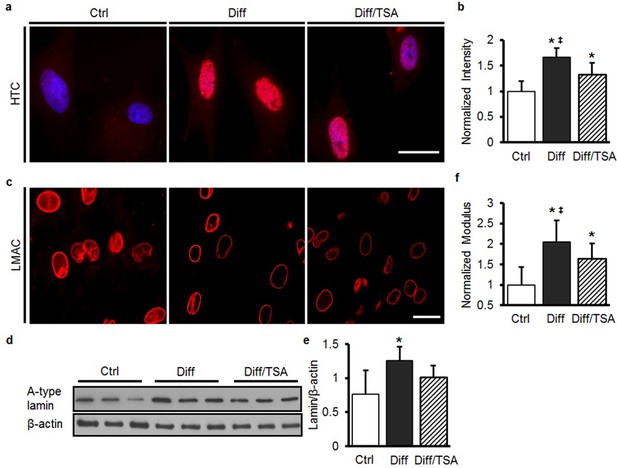

TSA treatment of differentiated MSCs softens nuclei and decreases heterochromatin, but does not alter Lamin A/C amount or distribution.

(a and b) One day of TSA treatment (Diff/TSA) decreased heterochromatin (HTC) staining in differentiated MSCs (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, ‡p < 0.05 vs. Diff/TSA, n = 35, mean ± SD). Scale: 20 µm. One day of TSA treatment (Diff/TSA) did not alter LMAC organization (c) or A-type lamin protein content (d and e, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs.Ctrl, n = 3, mean ± SD). Scale 20 µm. (f) One day of TSA treatment (Diff/TSA) decreased nuclear stiffness in differentiated MSCs (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, ‡p < 0.05 vs. Diff/TSA, n = 10, mean ± SD).

TSA treatment of differentiated MSCs does not alter MLCK activity, actin structure, or migration speed.

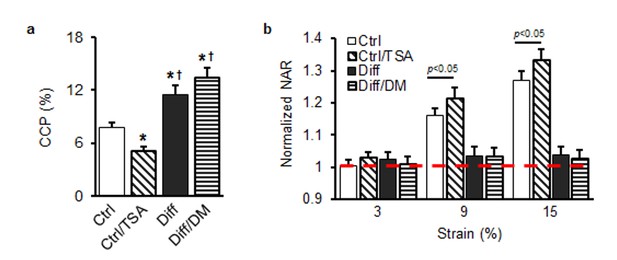

DM treatment induces chromatin reorganization but does not perturb the actin cytoskeleton.(a and b) MLCK phosphorylation increased markedly in Diff compared to Ctrl MSCs but was not altered with TSA treatment (Diff/TSA, ANOVA, *p>0.05 vs. Diff/TSA, n = 3, mean ± SD). (c) There were no apparent changes in actin stress fiber density or distribution with differentiation (Diff) or TSA treatment (Diff/TSA), scale: 20 µm. (d and e) Differentiation slowed MSC migration in a wound healing assay; TSA treatment (Diff/TSA) did not alter migration rates (*p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, ‡p<0.05 vs. 1 hr, n = 6, mean ± SD, Scale: 200 µm). Visualization (f) and quantification (g) of chromatin condensation parameter (CCP) with DM treatment of MSCs (Ctrl/DM, Student’s t-test, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, n =~30, mean ± SD, scale: 3 µm). (h) Phalloidin staining of actin under Ctrl and DM treatment conditions (Ctrl/DM). Scale: 100 µm.

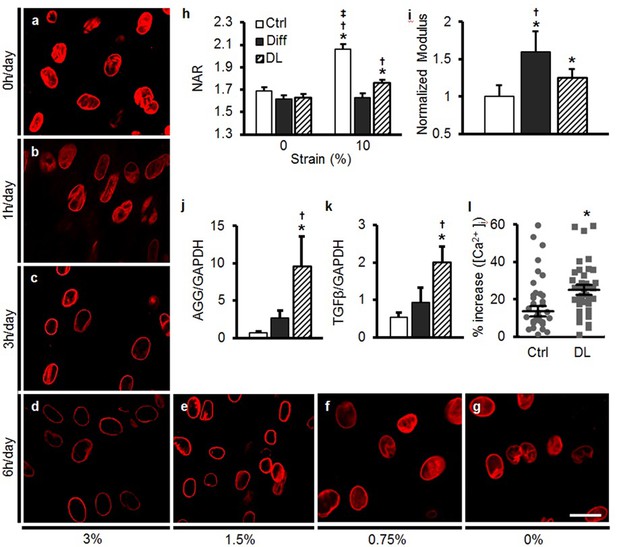

Dynamic loading induces nuclear reorganization and increases nuclear mechanics in undifferentiated MSCs.

Dynamic loading (DL) for 5 days in the absence of soluble differentiation factors resulted in reorganization of LMAC in a manner dependent on the duration (0, 1, 3, or 6 hr/day, a–d) and magnitude (0, 0.75, 1.5, and 3% dynamic strain applied at 1 Hz, d–g) of applied loading (Scale: 20 µm). (h) DL (6 hr, 3%) decreased changes in NAR with 10% static stretch (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. 0%, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, ‡p<0.05 vs. DL, n = 52, mean ± SEM, experiments were carried out in triplicate). (i) DL nuclei were stiffer than those in undifferentiated MSCs, but were not as stiff as nuclei in MSCs differentiated (Diff) through soluble factor addition (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. DL, n = 10, mean ± SD, experiments were carried out in duplicate). (j and k) DL increased expression of AGG and TGF-β to levels exceeding those of differentiated MSCs (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, n = 5, mean ± SD, experiments were carried out in triplicate). (l) A rapid 10% stretch applied to DL-conditioned MSCs resulted in higher intracellular calcium release compared to the same perturbation of Diff MSCs (Student’s t-test, *p<0.05, n =~40, mean ± SEM, experiments were carried out in duplicate). See Figure 5—source data 1 .

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Changes in nuclear aspect ratio with stretch, peri-nuclear stiffness, and gene expression with the application of DL.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.018

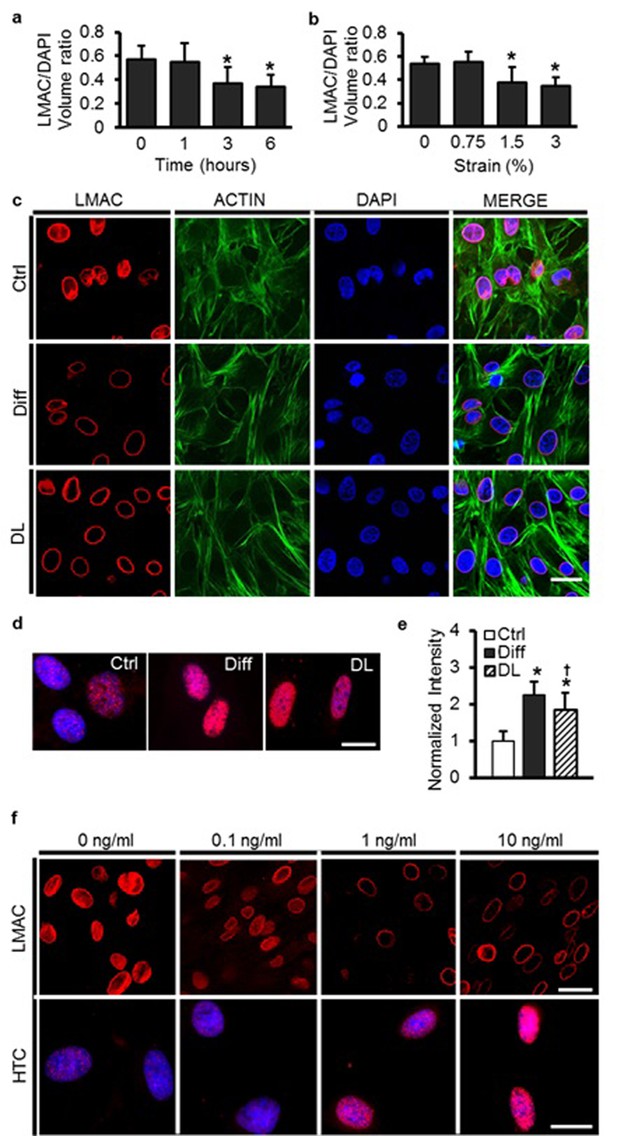

Dynamic loading of undifferentiated MSCs induces nuclear reorganization comparable to differentiation with soluble factors.

LMAC nuclear occupancy ratio as a function of strain duration (a) and magnitude (b) in MSCs dynamically loaded in Ctrl media (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. 0%/0 hr, n = 25, mean ± SD). (c) LMAC was restricted to the nuclear periphery with differentiation. After DL (6%, 5 days) in Ctrl media, LMAC organization closely mirrored that of differentiated MSCs. There was no clear change in actin stress fibers with differentiation or with application of dynamic loading (DL), scale: 20 µm. (d and e) Heterochromatin staining intensity increased with dynamic loading (DL), reaching levels similar to that of differentiation medium (Diff, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, n = 30, mean ± SD, scale: 3 µm). (f) LMAC reorganization and heterochromatin formation (HTC) was evident at TGF-β3 doses ≥1 ng/mL [at one week, scale: 20 µm (top) or 3 µm (bottom)].

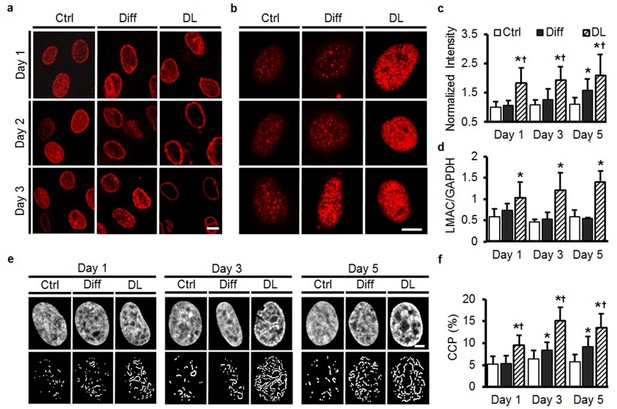

Rapid alterations in MSC nuclear architecture with dynamic loading.

(a) Staining for LMAC showed little change in Ctrl conditions, and only subtle changes in Diff conditions through day 3. Conversely, DL promoted LMAC reorganization as early as day 2 (Scale: 5 µm). (b) Heterochromatin staining was evident in Ctrl conditions on day 3, but was already present on day one in DL conditions (Scale: 5 µm). (c) Quantification of heterochromatin staining showed significant differences in the DL group as early as day 1 (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, n = 35, mean ± SD, experiments were carried out in duplicate). (d) DL increased LMAC gene expression at each time point (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl conditions, n = 3. Mean ± SD, experiments were carried out in triplicate). (e) Representative DAPI stained nuclei on days 1 through 5 with treatment (top row), and corresponding edge detection for CCP calculation (bottom row). Scale: 2 µm. (f) Chromatin condensation parameter (CCP) as a function of treatment group and time (ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, n = 29–31 cells per condition per time point, mean ± SD, experiments were carried out in duplicate). See Figure 6-source data 1 and Source code 1 .

-

Figure 6—source data 1

HTC staining intensity, LMAC gene expression and CCP calculation.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.021

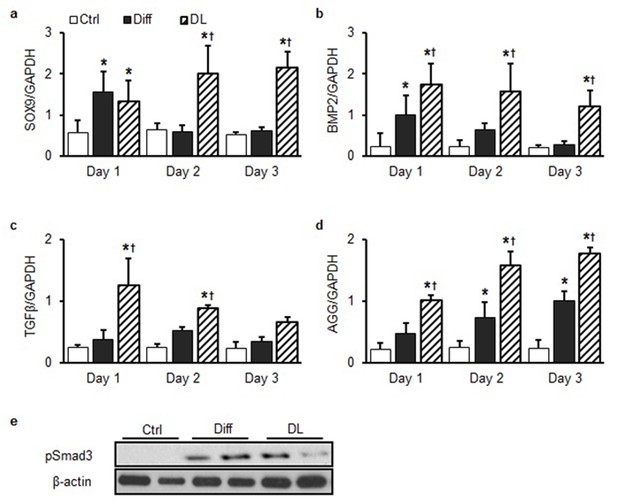

Rapid changes in fibrocartilaginous gene (Sox9, BMP2, TGF-β, and Aggrecan) expression with dynamic loading.

Expression of (a) SOX9, (b) BMP2, (c) TGF -β, and (d) aggrecan (AGG) was transiently upregulated under Diff conditions over the first three days of culture. DL resulted in higher expression for longer durations (DL: 6 hr/day, ANOVA, *p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Diff, n = 3, mean ± SEM). (e) Smad3 phosphorylation increased markedly in Diff or DL compared to Ctrl MSCs.

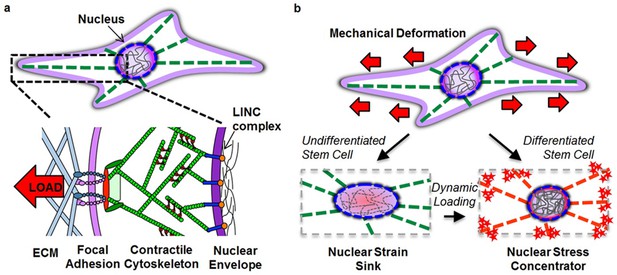

Altered nuclear mechanobiology with stem cell differentiation.

(a) The nucleus is mechanically linked to the extracellular environment through linker of nucleus and cytoskeleton (LINC) complex connections to a contractile cytoskeleton that interact with the extracellular matrix (ECM) through focal adhesion complexes. (b) When progenitor cells differentiate, the nucleus transforms from a deformable ‘strain sink’ into a comparatively rigid (relative to the cytoskeleton) ‘stress concentrator’, with localization of Lamin A/C to the nuclear envelope (red circle in nucleus) and an increase in heterochromatin content (grey lines in nucleus). In the undifferentiated state, the nucleus deforms along with the cell, resulting in little added strain (or stress) in the cytoskeleton (green filaments). In the differentiated state, the lack of deformation of the nucleus concentrates deformation (and stress) in the cytoskeletal network (red filaments) and at its connections. This transformation hyper-sensitizes the differentiated cell to respond to mechanical perturbation (red stars) by increasing stress at each point of cytoskeletal connectivity (focal adhesions and LINC complex). Mechanical inputs (when repeated dynamically) can evoke similar changes in nuclear architecture and mechanics and increase cell mechanosensitivity to direct lineage specification in the absence of exogenous soluble differentiation factors.

(a) Chromatin condensation parameter (CCP) as a function of treatment group (*p<0.05 vs. Ctrl, †p<0.05 vs. Ctrl/TSA, n = 24). (b) Normalized nuclear aspect ratio (NAR) as a function of treatment group and applied stretch [normalized to NAR values at 0% (dashed line), n = 57 ~ 65).

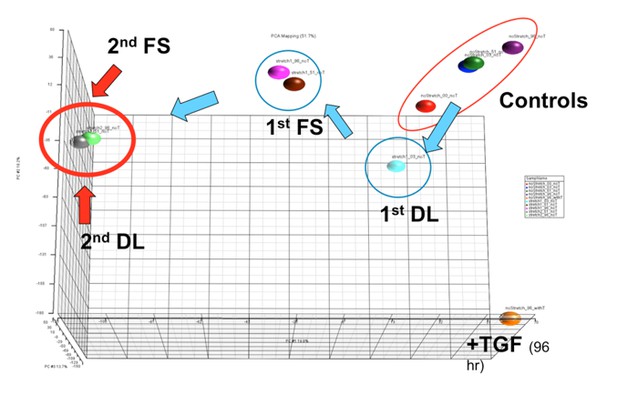

PCA plot showing shifts in global gene expression in response to one loading event (DL), after a period of free swelling culture (FS) following DL, after a second loading event (2nd DL), and with another free swelling period (2nd FS).

Note that the last two points (green and grey) reside essentially on top of one another, suggesting a permanence in expression patterns across the genome following a second loading event. These positions are quite distinct from that arrived at by TGFbeta treatment (+TGF) in the absence of load over a similar time course.

Videos

3D reconstruction of LMAC in the nucleus in undifferentiated bovine MSCs.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.0113D reconstruction of LMAC in the nucleus in differentiated bovine MSCs.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.012Additional files

-

Source code 1

MATLAB code for calculation of chromatin condensation parameter (CCP).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18207.024