Locus coeruleus to basolateral amygdala noradrenergic projections promote anxiety-like behavior

Figures

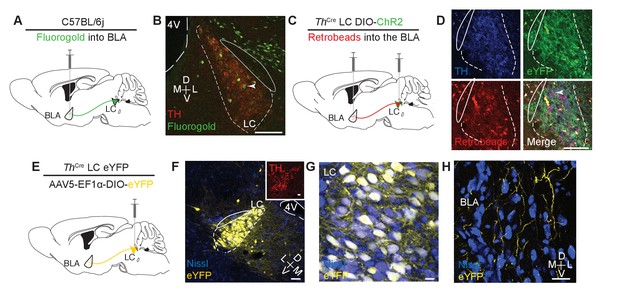

Identifying a LC input to the BLA.

(A) Cartoon depicting fluorgold tracing strategy. (B) Representative image (selected from three injected mice) shows robust retrograde labeling of the LC from injection in the BLA (green = pseudocolored Fluorgold, tyrosine hydroxylase = red). Arrowhead indicates example co-localization. Scale bar = 100 µm. 4V = 4th ventricle. The TH- cells dorsal and ventral to the LC are likely part of the medial parabrachial nucleus which has previously identified projections to the BLA (Saper and Loewy, 1980). (C) Cartoon depicting dual injection tracing strategy for CTB-594 and DIO-ChR2-eYFP. (D) Representative images (selected from three injected mice) shows retrograde labeling in LC of red retrobeads and anterograde labeling of TH+ cells (green) (Nissl=blue). Arrowhead indicates example co-localization. Scale bar = 100 µm (E) Cartoon depicting anterograde tracing strategy. (F–H) Coronal images depict robust eYFP (yellow) labeling in the LC (F and G) and BLA (H) of the same mouse (scale bars = (F) 50 µm, (G) 10 µm, (H) 20 µm. Inset (F), tyrosine hydroxylase = red, scale bar = 25 µm.

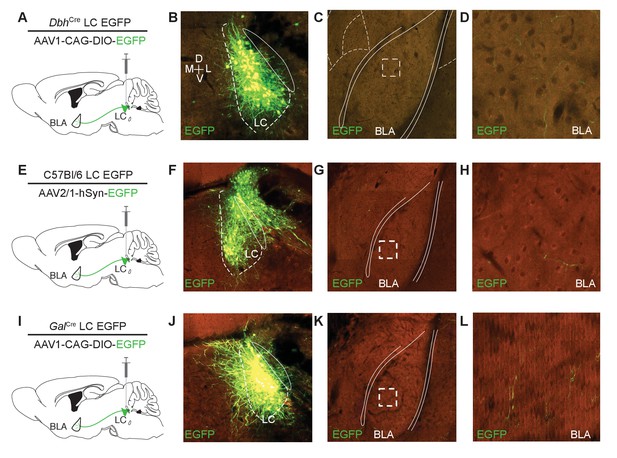

Further identification of LC input to the BLA.

Three experiments from the Allen Institute depict converging LC-BLA projections across targeting strategies. (A) Cartoon depicting cell-type selective anterograde tracing strategy employed by the Allen Brain Institute for Dopamine beta hydroxylase-Cre (DbhCre) mice (Oh et al., 2014). (B–D) Serial two-photon tomography images depict robust EGFP labeling in the LC (B) and BLA (C and D) of the same mouse. Dashed box in C indicates boundary of D. (E) Cartoon depicting non-cell-type-selective anterograde tracing strategy employed by the Allen Brain Institute for C57Bl/6 mice (Oh et al., 2014). (F–H) Serial two-photon tomography images depict robust EGFP labeling in the LC and surrounding areas (F) and BLA (G and H) of the same mouse. Dashed box in G indicates boundary of H). (I) Cartoon depicting cell-type selective anterograde tracing strategy employed by the Allen Brain Institute for GalaninCre mice (Oh et al., 2014). (J–L) Serial two-photon tomography images depict robust EGFP labeling in the LC (J) and BLA (K and L) of the same mouse. Dashed box in K indicates boundary of L. Background color is result of background fluorescence across channels. Image clarity is as maintained in the ABIMC database for K and L.

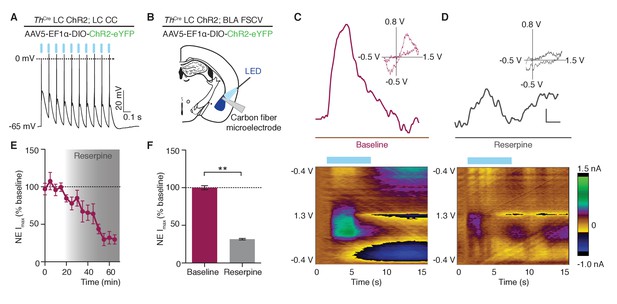

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA releases norepinephrine.

(A) LC neuron firing reliably to 10 Hz optical stimulation (CC=whole cell current clamp). (B) Fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) schematic. (C–D) Oxidative and reductive currents (scale bar 2 s by 0.4 nA), with representative cyclic voltammograms (inset) and representative color plots (below) in response to photostimulation are attenuated by reserpine (1 μM). Color plots for baseline and after reserpine (1 µM): Files were collected over 15 s (X-axis) where the carbon fiber microelectrode was ramped with a triangular waveform from −0.4V to 1.3V and back to −0.4V at 400 V/S (Y-axis) and sampled at 10 Hz. 10 Hz, 473 nm blue LED stimulation onset at 2 s. Oxidative currents (nA) are positive in direction and reductive currents are negative (see color coded scale bar on right). (E) Attenuation in NE oxidative current in response to reserpine (1 μM) n = 3 pairs; mean ± S.E.M). (F) Average of first 20 min and last 15 min in (E) (Data represented as mean ± SEM, Paired Student’s t-tests to baseline, Mean difference = 68.56, t(2) = 18.75, **p=0.0028, 95% CI [52.82 to 84.29]).

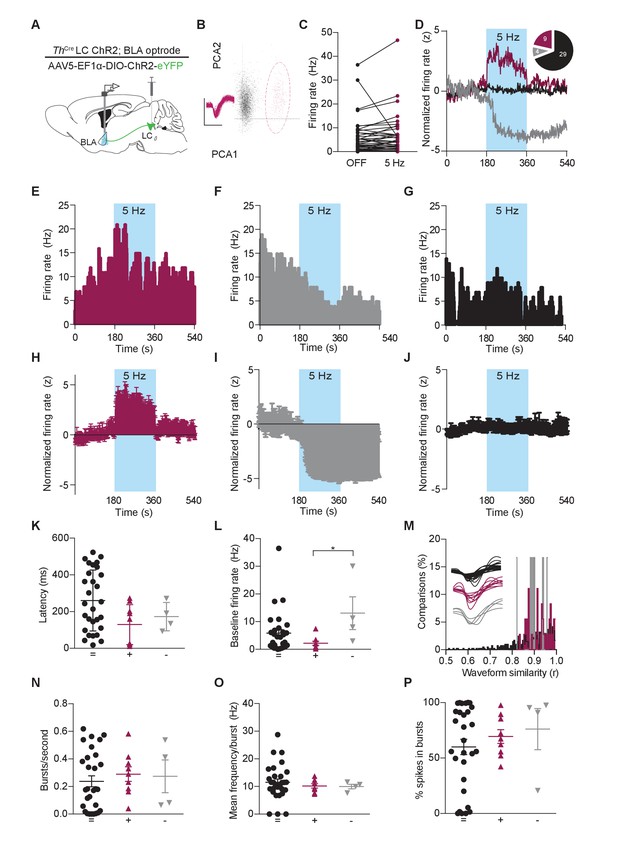

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA alters neuronal activity.

(A) Schematic illustrating single-unit extracellular recording paradigm of BLA neurons modulated by ChR2-expressing LC-BLA terminals. (B) Representative principal component analysis plot showing the first two principal components with clear clustering of a single unit (maroon) from the noise (grey). Inset shows the waveform and spikes making up the isolated unit. Y-scale is 150 microvolts and x-scale is 500 ms. (C) Recordings from eight hemispheres of six Th-CreLC-BLA:ChR2 mice show the distribution of firing rates present in BLA neurons prior to and following LC-BLA terminal photostimulation (473 nm, 5 Hz, 3 min). (D) Average normalized firing rate of neurons that increase (maroon), decrease (grey), or do not change (black) firing rate in response to photostimulation. Inset, shows number of neurons in each group. Representative histograms (1 s bins) of isolated single-units showing increase (E) or decrease (F), or no change (G) in neuronal firing in response to photostimulation (473 nm, 5 Hz, 3 min). Z-scored population responses of neurons showing increase (H) or decrease (I), or no change (J) in neuronal firing in response to photostimulation. (K) Response latency following onset of photostimulation for cells that did not alter firing (=) (n = 29), increased firing (+) (n = 9), or decreased firing (-) (n = 4). (Data represented as mean ± SD). (L) The same cells sorted by baseline firing rate. (Data represented as mean ± SEM. Kruskal-Wallis test one-way ANOVA for non-parametric data with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, Kruskal-Wallis statistic = 6.536, p=0.0381; + vs. – Mean rank difference = −18.75, adjusted *p=0.0329; + vs. + Mean rank difference = −6.828, adjusted p=0.4341; - vs. = Mean rank difference = 11.92, adjusted p=0.2053.) (M) Waveform similarity, within group distribution of linear correlations. Inset, every average waveform for each recorded unit separated by response profile (= black, + maroon, - grey). (N–P) Bursting profiles for each recorded neuron. (N) Number of bursts per second. (Data represented as mean ± SEM). (O) Mean firing rate within bursts for each neuron. (Data represented as mean ± SEM). (P) Proportion of recorded spikes that occurred during bursts. (Data represented as mean ± SEM).

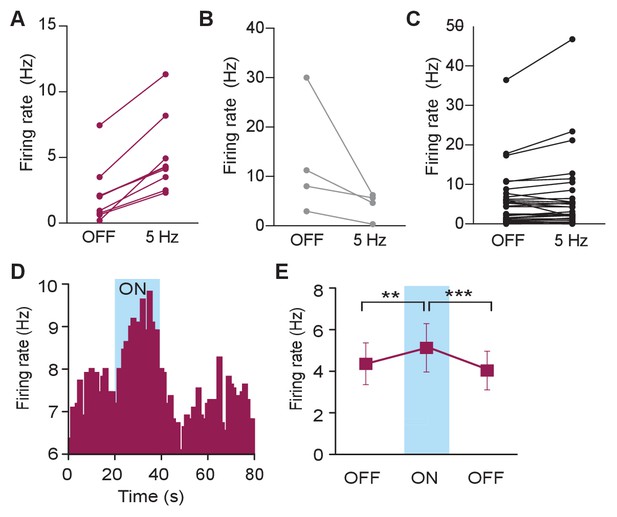

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA alters neuronal activity.

(A–C) The same data shown in Figure 3C, but separated to clearly show which neurons were classified as increasing (A), decreasing (B), or no change (C). Please note that while some units in (C) appear to increase or decrease, these did not meet the criteria to be classified as increasing or decreasing. (D) Representative histogram of isolated single-unit shows an increase in neuronal firing in response to constant photostimulation (473, constant light, 20 s). (E) Neuronal firing rate increases in response to 20 s (473 nm, constant light) photostimulation and returns to baseline values in the absence of light (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n = 10, One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc comparison test, F2,9 = 14.62, p=0.0002; OFF1 vs. ON Mean difference = 0.7673, t(2) = 3.70, **p<0.01 95% CI [−1.31 to −95.80]; OFF1 vs. OFF2 Mean difference = 0.3234, t(2) = 1.56, p>0.05, 95% CI [−0.22 to 0.87]; ON vs. OFF2 Mean difference = 1.091, t(2) = 5.26, ***p<0.001 95% CI [0.54 to - to 1.63]).

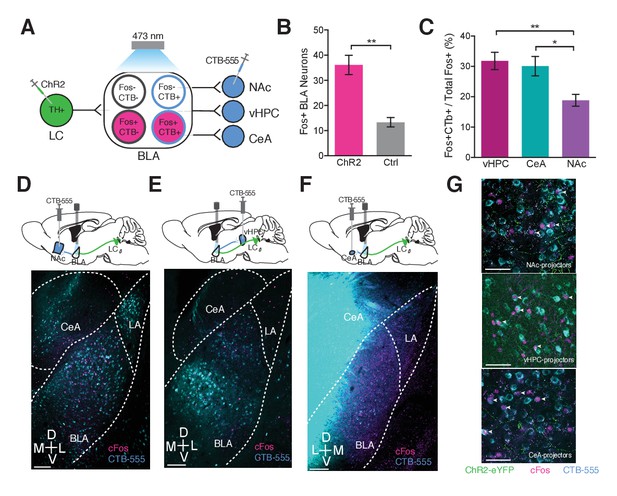

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA preferentially activates BLA circuitry associated with anxiety-like behavior.

(A) Diagram of viral and optogenetic strategy. (B) 5 Hz photostimulation increases cFos expression within the BLA in ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2+ animals compared to ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2- controls (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n = 9 ChR2, n = 4 Ctrl; average of 3 sections/mouse; Student’s t-test, Mean difference = 19.17, t(10) = 4.005, **p=0.0040, 95% CI [−35.47 to −10.11). (C) 5 Hz photostimulation increases cFos expression significantly more in BLA neurons projecting to the vHPC and CeA compared to NAc in ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2 animals (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n = 9 vHPCCTB, n = 6 CeACTB, n = 9 CeACTB, 3 sections per mouse; One-Way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test, F2,20 = 7.199, **p=0.0044; ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2:CTB-vHPC vs. ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2:CTB-NAc Mean difference = 12.95, t(20) = 3.585, **p<0.01 95% CI [3.511 to 22.39]; ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2:CTB-CeA vs. ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2:CTB-NAc. Mean difference = 11.25, t(20) = 2.802, *p<0.05 95% CI [0.7605 to 21.74]. Representative images of the BLA expressing cFos after 5 Hz photostimulation in (D) ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2 injected with CTB in NAc, (E) vHPC, or (F) CeA. Scale bar, 100 µm. (G) Confocal images showing colocalization of CTB and cFos after 5 Hz photostimulation in the NAc, vHPC, and CeA. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA preferentially activates BLA circuitry associated with negative affect.

Representative images of the BLA expressing cFos after 5 Hz photostimulation in (A and C) ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2- and (B and D) ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2+. Scale bars, 100 µm. (D) 5 Hz photostimulation increases cFos expression within the BLA of ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2 animals relative to its contralateral side (One-sample t-test, theoretical mean of 1.0 ratio, Actual mean = 3.755, ***p<0.0001, t(22) = 8.923, 95% CI [2.115 to 3.395). (F–G) Representative images of injection sites of CTB in the (F) NAc, (G) vHPC, (H) CeA. Scale bars, 500 µm.

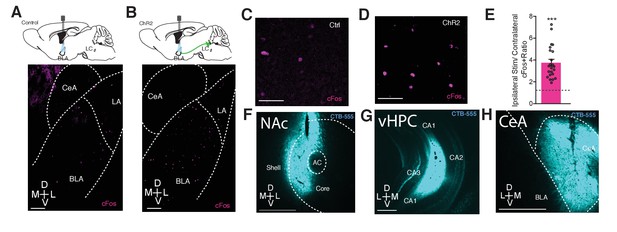

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA causes conditioned aversion.

(A) Cartoon of viral and fiber optic delivery strategy and calendar of real-time place testing studies. (B) Representative traces of behavior at different frequencies. (C) Frequency response of RTPT and (D) locomotor activity at 5 and 60 Hz. Data represented as mean ± SEM, n = 4 eYFP, 5 ChR2. (E) Conditioned place aversion (CPA) behavioral calendar. (F) Representative CPA traces. (G) ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2 mice (maroon; n = 9) show a conditioned aversive response to chamber paired with photostimulation compared to ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:eYFP controls (grey; n = 8) (Data represented as mean ± SEM, Student’s t-test, Mean difference = 131.3, t(15) = 2.39, *p=0.0303, 95% CI [14.32 to 248.4) following two days of conditioning with (H) no significant differences in locomotor behavior during conditioning day 1 (CD1) and or conditioning day 2 (CD2) in CPA.

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA drive aversive behavior.

(A) Fiber optic tip placements for the RTPA experiment. (B) Fiber optic tip placements for the CPA experiment. Animals were excluded if the fiber tip ended >1 mm dorsal or any caused significant lesion to the BLA.

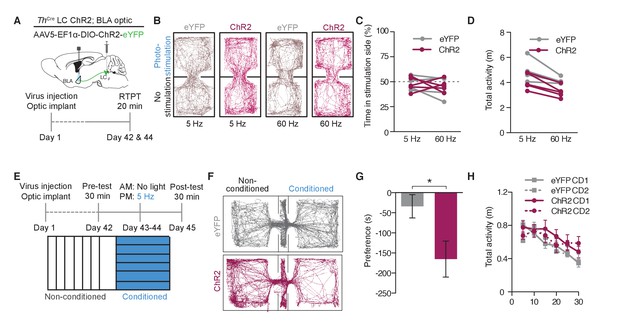

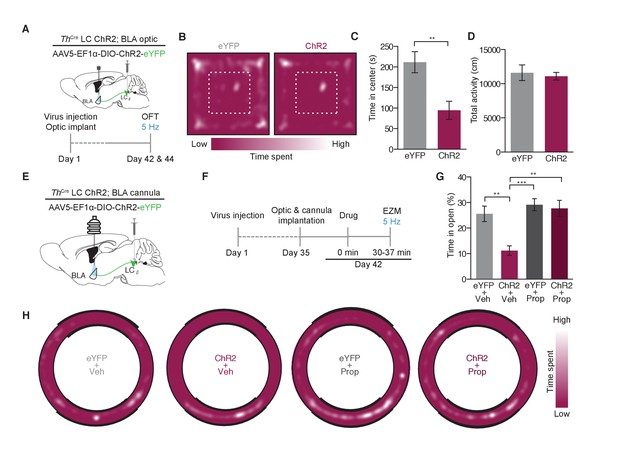

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA promotes anxiety-like behavior through beta-adrenergic receptors.

(A) Calendar of OFT studies. (B) Representative heat maps of activity during OFT. (C) 5 Hz photostimulation causes an anxiety-like phenotype in OFT of ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2 animals compared to ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:eYFP controls (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n = 10 eYFP, 11 ChR2; Student’s t-test, Mean difference = 116.9, t(19) = 3.46, **p=0.0026, 95% CI [46.20 to 187.5) with (D) no change in locomotor activity (Data represented as mean ± SEM). (E) Cartoon of viral, cannula, and fiber optic delivery strategy and (F) calendar of EZM behavior. (G) 5 Hz photostimulation causes an anxiety-like phenotype in EZM of ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2 animals compared to ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:eYFP controls, which is reversed by intra-BLA propranolol pretreatment (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n = 11 eYFP + Vehicle, n = 9 ChR2 + Vehicle, n = 7 eYFP + Propranolol, n = 8 ChR2 + Propranolol; One-Way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test, F3,31 = 8.95, p=0.0002; ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:eYFP+Vehicle vs. ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2+Vehicle. Mean difference = 14.74, t(2) = 3.94, **p<0.01 95% CI [4.21 to 25.27]; ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2+Vehicle vs. ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2+Propranolol. Mean difference = 16.93, t(2) = 4.19, **p<0.01 95% CI [5.46 to 28.31]; ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:eYFP+Propranolol vs. ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2+Vehicle. Mean difference = 18.37, t(2) = 4.39, ***p<0.001 95% CI [6.57 to 30.18). (H) Representative heat maps of activity during EZM.

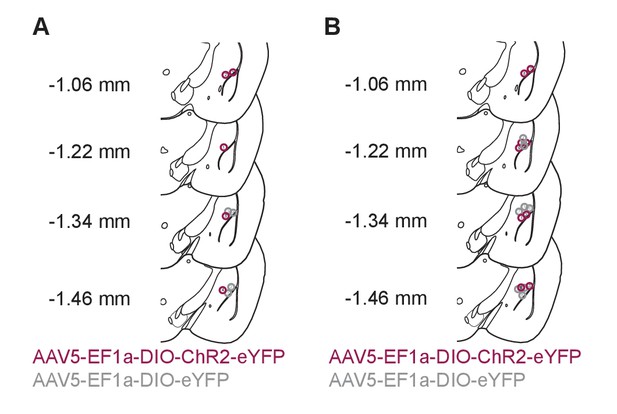

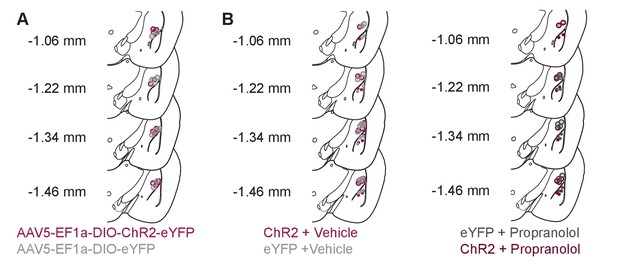

Photostimulation of LC terminals in the BLA drive anxiety-like behavior.

(A) Fiber optic tip placements for the OFT experiment. Animals were excluded if the fiber tip ended >1 mm dorsal or any caused significant lesion to the BLA. (B) Cannula and fiber optic tip placements for the EZM experiments with ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:ChR2 and ThIRES-Cre::LC-BLA:eYFP animals. Animals were excluded if the fiber tip ended >1 mm dorsal or any caused significant lesion to the BLA. Additionally, cannulated mice were excluded if the final injection placement appeared to be >0.5 mm from the BLA. For clarity, only hits of included mice for this experiment are shown.