EED orchestration of heart maturation through interaction with HDACs is H3K27me3-independent

Figures

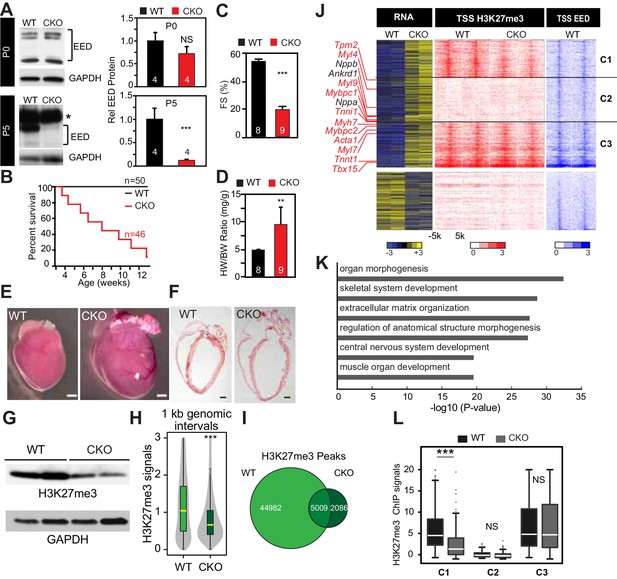

Neonatal cardiomyocyte inactivation of Eed caused lethal dilated cardiomyopathy.

(A) EED protein expression in WT and cardiac EedCKO (CKO, Myh6-Cre+;Eedf/f) on postnatal days 0 (P0) and 5 (P5). Quantification shows relative EED protein normalized to GAPDH loading control. Several splice isoforms of EED were detected. * indicates a non-specific band that is larger than full length EED's predicted molecular weight. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of WT and EedCKO mice. (C) Heart function was measured by echocardiography as fractional shortening (FS%) at 2 months of age. See Figure 1—figure supplement 2A for FS% at earlier time points. (D–F) Cardiac dilatation and hypertrophy were observed by heart to body weight ratio (D), gross morphology (E), and histology (F) in WT and EedCKO at 2 months of age. Representative hearts are shown. Bar = 1 mm. (G) Immunoblotting for H3K27me3 in cardiomyocytes from WT and EedCKO at 2 months of age. (H) Genome-wide distribution of H3K27me3 ChIP-seq signals in WT and EedCKO purified cardiomyocytes. ChIP-seq signal was measured in 1 kb windows across the genome. The signal distribution is displayed as a violin plot. Yellow lines denote the median value. (I) Venn diagram showing the distribution of H3K27me3 peaks in WT and EedCKO heart. (J) Heat map of RNA transcript levels of differentially expressed genes (fold-change >1.5 or <0.67 and adjusted p-value<0.05) are shown in the left heatmap. Expression values for each gene were row scaled. Selected contractile myofiber and heart failure marker genes are shown in red and black, respectively. Right heatmap shows H3K27me3 and EED ChIP-seq signal at the transcriptional start site (TSS) of the differentially expressed gene on the same row. Gene expression, H3K27me3, and EED ChIP-seq studies were performed on purified cardiomyocytes at 2 months of age. Rows were ordered by k-means clustering on H3K27me3 and EED ChIP-seq signal into three clusters, C1-C3. (K) Gene Ontology analysis of differentially expressed genes between WT and EedCKO. The top six significant terms are shown. (L) Box plots showing H3K27me3 signals in these three clusters as shown in J. A, C, D, Student’s t-test; H, L, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, NS, not significant. Numbers in bars indicate independent biological replicates.

Eed depletion in WT and EedCKO mice.

Heart apexes were harvested for qRT-qPCR for relative Eed mRNA expression on postnatal days 0 (P0) and 5 (P5). Heart apex contains both cardiomyocytes and non-cardiomyocytes. The non-myocytes likely account for the detected level of Eed mRNA in EED-CKO. p-Value by Student’s t-test. ***p<0.001. NS, not significant.

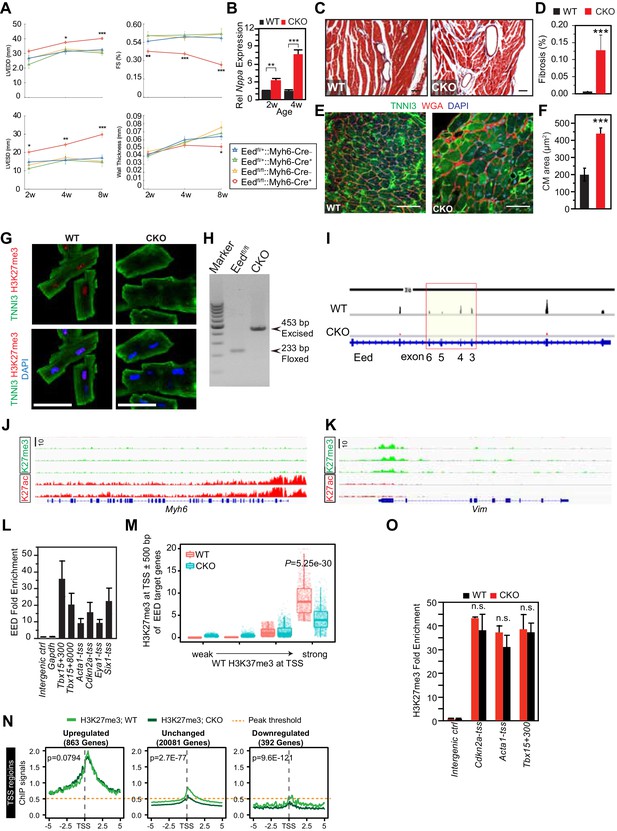

Characterization of EedCKO mice.

(A) Progressive cardiac dysfunction and dilatation after cardiomyocyte-restricted ablation of Eed. w, weeks. (B) Nppa mRNA level in WT and CKO hearts at the indicated ages. w, weeks. (C, D) Cardiac fibrosis was evident by Mason Trichrome staining at 2 months of age. Fraction of myocardial area occupied by fibrotic tissue (blue staining) was quantified using ImageJ. Bar = 50 µm. (E, F) Immunofluorescence for cardiomyocyte marker TNNI3 and cardiomyocyte membrane marker WGA, and quantification of cell size from WGA-stained cardiomyocyte outlines (f). Bar = 50 µm. (G) Immunostaining for TNNI3 and H3K27me3. Isolated adult cardiomyocytes were >95% pure and EedCKO CMs had little H3K27me3 signal. Bar = 50 µm. (H) PCR of genomic DNA from purified CMs using primers that amplify unexcised floxed DNA (233 bp product) or Cre-excised DNA (453 bp product). In CKO-purified CMs, unexcised floxed DNA was not detected, consistent with highly efficient Cre-mediated gene inactivation, as well as high purity of dissociated CMs. (I) RNA-seq track view showing deletion of floxed exons 3–6 of Eed (red box). (J,K) Genome browser view ofH3K27me3 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals on Myh6 (J) and Vim (K) loci in purified adult cardiomyocytes. (L) EED enrichment on downstream genes was measured by ChIP-qPCR in P5 heart ventricle apex. Numbers following gene names indicate the number of nucleotides between the probed amplicon and the TSS. (M) Box and scatter plots of H3K27me3 at TSS ±500 bp of EED target genes in four quantiles of WT H3K27me3 intensity. (N) Aggregation plots of H3K27me3 ChIP-seq signals near the TSS of genes upregulated, downregulated, or unchanged between WT and EEDCKO. O. H3K27me3 enrichment was measured by ChIP-qPCR on target genes using adult cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and EEDCKO hearts. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc test using Eedfl/+::Myh6-Cre– as the control group (A), by Welch’s t-test (B,D,F,N,O), or by Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (M).

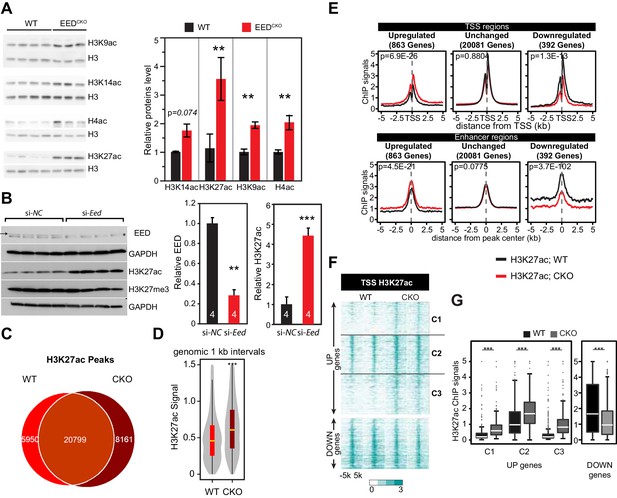

Eed depletion induced globally elevated histone acetylation.

(A) Global upregulation of histone H3 and H4 acetylation at different lysine residues in isolated adult cardiomyocytes from 2-month-old WT and EedCKO hearts. Histone levels were measured by immunoblotting and further quantified by normalization to total histone H3. (B) Acute EED depletion increased H3K27ac levels in HL-1 cardiomyocyte-like cells. Fully confluent HL-1 cells were transfected with TriFECTa DsiRNAs against Eed (si-Eed) or scrambled sequence-negative control (si-NC). Protein levels were measured by quantitative immunoblotting. Arrow, EED band. Asterisk, non-specific band. (C) Venn diagram showing the overlap of H3K27ac ChIP-seq peaks in isolated cardiomyocytes from WT and EedCKO hearts at 2 months of age. (D) Genome-wide distribution of H3K27ac signals. The violin plot displays H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals in 1 kb windows across the genome. Yellow horizontal lines denote median values. (E) Aggregation plots of H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals at ±5 kb of TSS (upper row) or at distal regions (lower row) of genes that were upregulated, downregulated, or unchanged by Eed inactivation. (F–G) Heat map (F) and box plots (G) of H3K27ac levels at TSS of differentially expressed genes. The row order and clustering is the same as in Figure 1J. A, B, Unpaired Student’s t-test; D,G, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; NS, not significant.

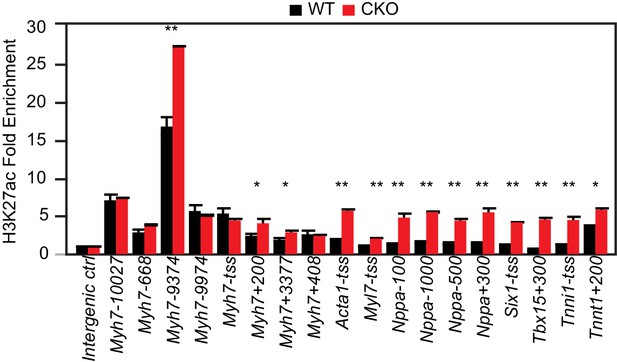

H3K27ac ChIP-qPCR validation.

H3K27ac enrichment was measured by ChIP-qPCR on target genes using adult cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and EEDCKO hearts. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 by Welch’s t-test.

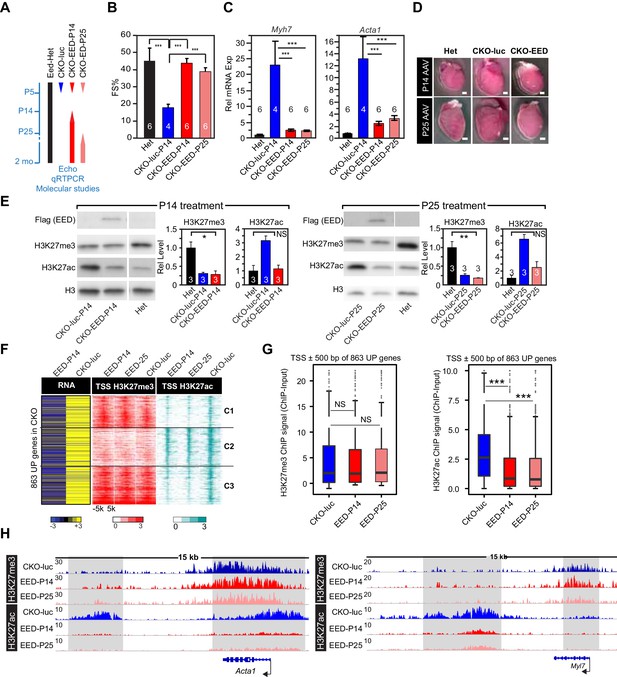

Delayed re-expression of EED rescued heart function and normalized H3K27ac but not H3K27me3.

(A) Schematic of the experimental design. AAV9 expressing EED or luciferase (luc) in cardiomyocytes was injected at P14, or P25 to control or EedCKO mice. Lines represent the temporal pattern of EED expression. (B–E) Heterozygous (Het; Eedfl/+; Myh6Cre+) and EedCKO mice were injected with AAV-luc or AAV-EED at indicated ages. At 2 months of age, heart function (FS%) was measured by echocardiography (B), and expression of Myh7 and Acta1, two slow-twitch myofiber genes aberrantly expressed in EedCKO, were measured by qRTPCR (C). Representative images showing gross morphology of hearts at 2 months of age (D). Cardiomegaly of CKO-luc hearts was abrogated by EED replacement at P14 or P25. Isolated cardiomyocytes were immunoblotted to measure expression of virally delivered EED, and global levels of H3K27ac and H3K27me3 (E) Graphs show quantitation of global H3K27ac and H3K27me3 levels, normalized to histone H3. (F) Heatmaps of RNA expression, H3K27me3 and H3K27ac ChIP signals at ±5 kb of TSS of 863 upregulated genes from EedCKO mice injected with AAV-luc or AAV-EED at P14 or P25. Row order and cluster labels are the same as Figure 1J. (G) Quantitative analysis of H3K27me3 and H3K27ac ChIP signals near TSSs shown in F by box plots. (H) Genome browser view of H3K27me3 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals at the Acta1 or Myl7 loci. The regions highlighted in gray show that gain of H3K27ac in EedCKO was reset to normal under EED rescue conditions regardless of H3K27me3 status. B, C, and E, Unpaired Student’s t-test; G, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

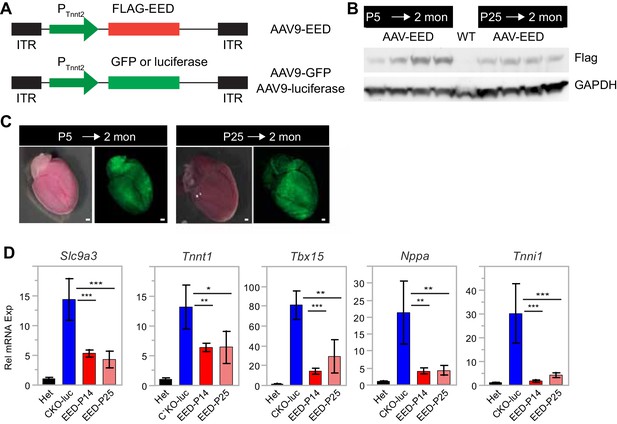

AAV9-EED rescue of EEDCKO mice.

(A) Schematic of AAV9 constructs expressing Flag-tagged EED (Flag-EED), GFP or luciferase. ITR, Inverted Terminal Repeart. PTnnt2, cardiac-specific troponin T promoter. (B) AAV9-EED expression of Flag-EED. Mice were treated with AAV9-EED at P5 or P25. Heart extracts were prepared at 2 months of age. WT, untreated wild-type mice. (C) Brightfield and GFP fluorescent signals in hearts of mice injected with AAV9-GFP at P5 or P25 and harvested at 2 months of age. Bar = 500 µm. (D) qRTPCR was performed to validate the expression of the indicated genes in cardiomyocytes from 2-month-old mice treated with AAV9-luc or AAV9-EED at P14 and P25.

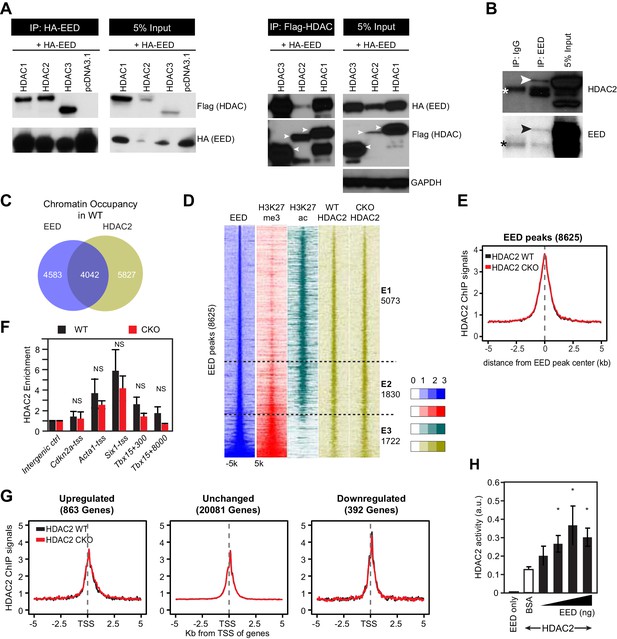

EED interacts with and co-localizes with HDAC to repress transcription through enhancing its deacetylation activity.

(A) Co-Immnoprecipitation analysis of EED-HDAC interaction in 293 T cells. HA-EED pull down with HA antibody co-precipitated FLAG-HDAC1/2/3 (left). Reciprocally, FLAG-HDAC1/2/3 pull down with Flag antibody co-precipitated HA-EED (right). Data on HA-EED and Flag-HDAC4-9 interaction are presented in Figure 4—figure supplement 1C,D. (B) Interaction between endogenous EED and HDAC2. EED, immunoprecipitated from HL-1 cardiomyocyte-like cells, co-precipitated HDAC2. Arrowhead denotes the specific band and asterisk denotes the non-specific IgG heavy chain band. (C) Venn diagram showing overlap of EED and HDAC2 peaks in WT. (D) Heatmaps showing ChIP-seq signals for EED, H3K27me3, H3K27ac and HDAC2 at ±5 kb of EED peak centers. Rows were sorted by ascending EED peak signal. (E) Aggregate plot showing HDAC2 ChIP signals in WT and EedCKO, centered on EED peak centers. (F) HDAC2 occupancy of the indicated chromatin regions in isolated cardiomyocytes from WT and EedCKO mice at 2 months of age. Occupancy was measured by ChIP followed by quantative PCR (ChIP-qPCR). Chromatin regions are named by the adjacent gene and the distance to the TSS. (G) Aggregation plot showing HDAC2 ChIP-seq signals in WT and EedCKO at ±5 kb of TSS of genes that were upregulated, unchanged or downregulated in EedCKO. (H) Effect of EED on HDAC2 activity. In vitro deacetylation assay was performed using recombinant active HDAC2 (50 ng) in the presence of BSA or 5 to 100 ng of recombinant EED, purified from insect cells. Deacetylation activity was measured by colorimetric assay. F, H, I, J, K, Unpaired Student’s t-test. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

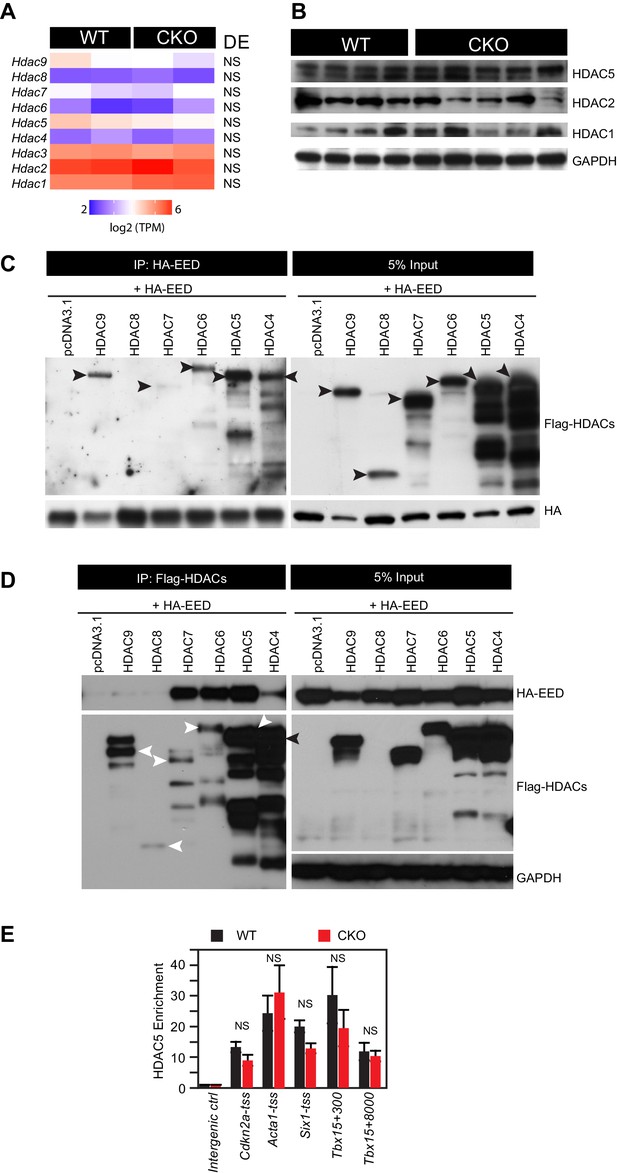

HDAC-EED interaction.

(A) RNA-seq data showing that HDAC transcript levels did not change in 2-month-old EedCKO cardiomyocytes. DE, Differential Expression; NS, not significant. (B) Immunoblotting for HDAC1, 2, and 5 proteins in adult cardiomyocytes isolated from hearts of control (WT) and EedCKO (CKO). (C) HA-EED, pulled down with HA antibody, co-immunoprecipitated HDAC4/5/6/7/9. HA-EED and HDAC4-9 were co-transfected into 293T cells and harvested for immunoprecipitation assay 48 hr after transfection. Arrowheads indicate full-length HDAC proteins. (D) Flag-HDAC4/5/6/7/9, pulled down with Flag antibody, co-immunoprecipitated HA-EED. Arrowheads indicate full-length HDAC proteins. (E) HDAC5 occupancy measurement by ChIP-qPCR. HDAC5 occupancy of the indicated chromatin regions in isolated adult CMs from WT and EedCKO mice at 2 months of age. Occupancy was measured by ChIP followed by quantative PCR (ChIP-qPCR). Chromatin regions are named by the adjacent gene and the distance to the transcriptional start site (TSS).

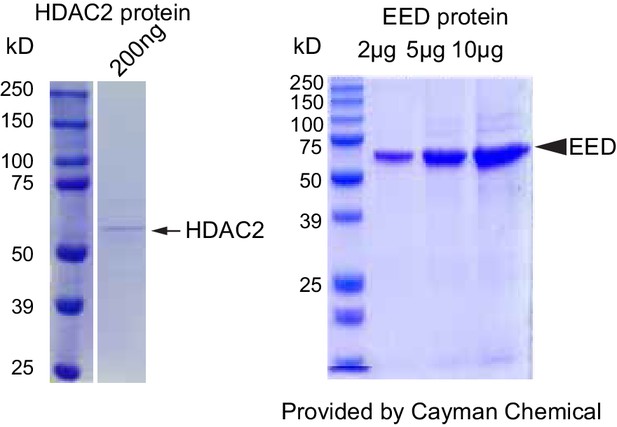

Validation of HDAC2 and EED proteins purity and dCas9-EED interaction with EZH2.

Coommassie brilliant blue staining of recombinant purified HDAC2 and EED proteins. The lot # specific staining gel image was proided by the manufacturer, Cayman Chemical.

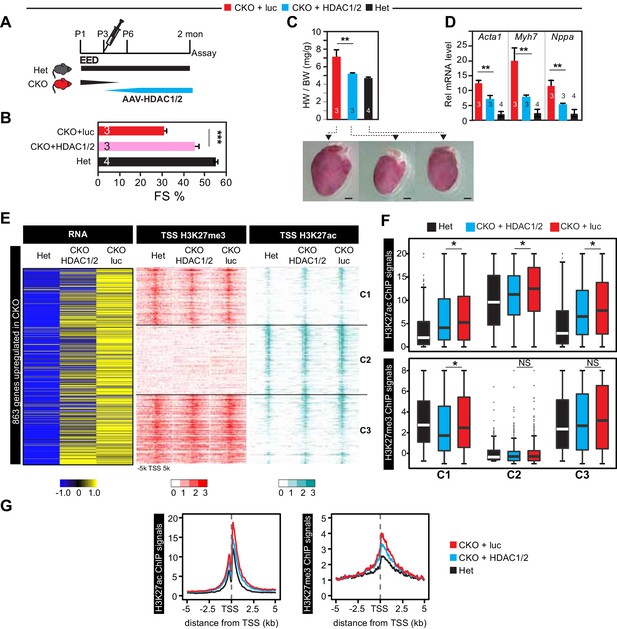

Re-introduction of HDAC1/2 restored normal heart function.

(A) AAV-HDAC1/2 rescue of EedCKO. Schematic shows the rescue experiment design. WT and CKO pups were injected with AAV-luc or AAV-HDAC1/2 at P3, and assays were done at 2 months of age. (B) Heart function (FS%) was measured at 2 months of age by echocardiography. (C) Gross morphology and heart to body weight ratio of hearts from mice at 2 months of age. Bar = 1 mm. (D) Analysis of heart failure gene expression. Acta1, Myh7, and Nppa levels in isolated cardiomyocytes were measured by qRTPCR. (E, F) Heatmaps (E) and box plots (F) showing ChIP signals for H3K27ac and H3K27me3 at ±5 kb of TSS of genes upregulated in EedCKO. Row order and cluster labels are the same as Figure 1J. Comparative analysis of ChIP-seq signals was performed within each cluster as indicated. (G) Aggregation plots for H3K27me3 or H3K27ac ChIP-seq signals at ±5 kb of TSS of EedCKO upregulated genes in Het, CKO+luc, and CKO+HDAC1/2 groups. B,C,D, Unpaired Student’s t-test. F, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

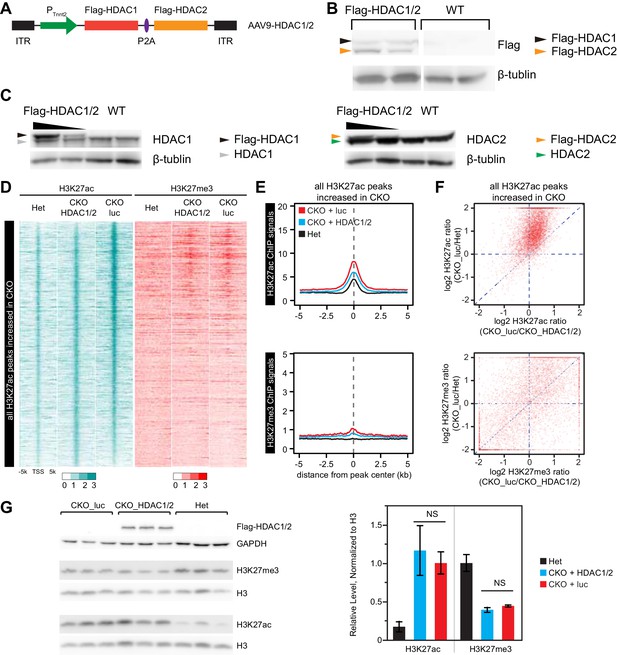

Effect of over-expression of HDAC1/2 on genome-wide H3K27ac and H3K27me3 accumulation at H3K27ac peaks with increased signal in EedCKO.

(A) Schematic of AAV9 construct expressing Flag-tagged HDAC1/2 (Flag-HDAC1/2). ITR, Inverted Terminal Repeart. (B) Validation of Flag-tagged HDAC1 and HDAC2 protein expression in AAV-treated hearts. Mice were treated with AAV9-Flag-HDAC1/Flag-HDAC2 or AAV9-Flag-EED at P3. Hearts were analyzed at 2 months of age. (C) Validation of ectopic and endogenous expression of HDAC1 and HDAC2 proteins in AAV-treated hearts of mice at 2 months of age. (D-F) Analysis of H3K27ac and H3K27me3 ChIP signals around all H3K27ac peaks gained in CKO, in het CKO_luc, and CKO_HDAC1/2. Heatmap (D) was sorted by descending value of the ratio of H3K27ac signal in CKO_luc to het. (E) aggregate plots of H3K27ac and H3K27me3 ChIP signals. (F) scatterplot of signal ratios comparing change in EED loss of function to change in HDAC1/2 rescue. Signals are from the peak center ±0.5 kb. (G) Immunoblotting and quantification of H3K27ac and H3K27me3 levels in adult cardiomyocytes isolated from hearts of three groups. H3K27ac or H3K27me3 immunoblot signals were normalized to total H3. NS, not significantly different.

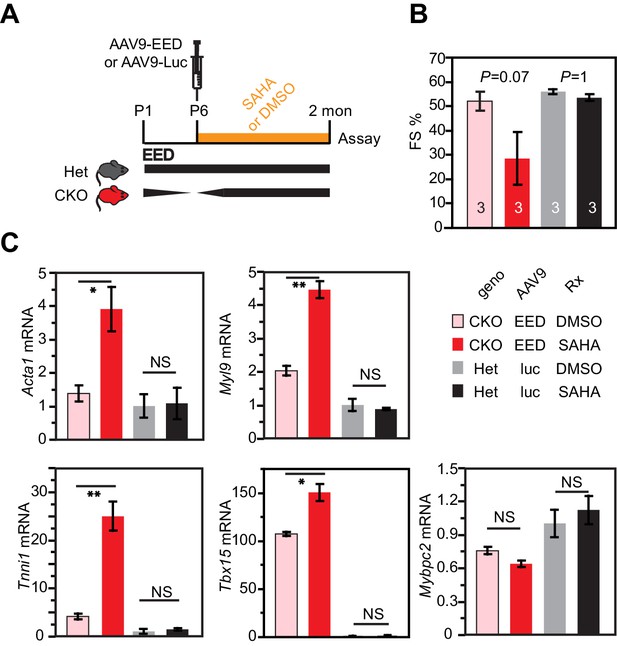

HDAC inhibition antagonized rescue of EedCKO by EED re-expression.

(A) Schematic of the experimental design. (B) Heart function was measured by echocardiography as fraction shortening (FS%) in 2-month-old EedCKO or Het mice that received the indicated treatments. Two of five EedCKO + EED + SAHA mice died prior to the study endpoint and were not available for echocardiography. (C) qRTPCR measurement of five selected genes that were aberrantly expressed in EedCKO hearts. P-value by Student’s t-test. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; NS, not significant.

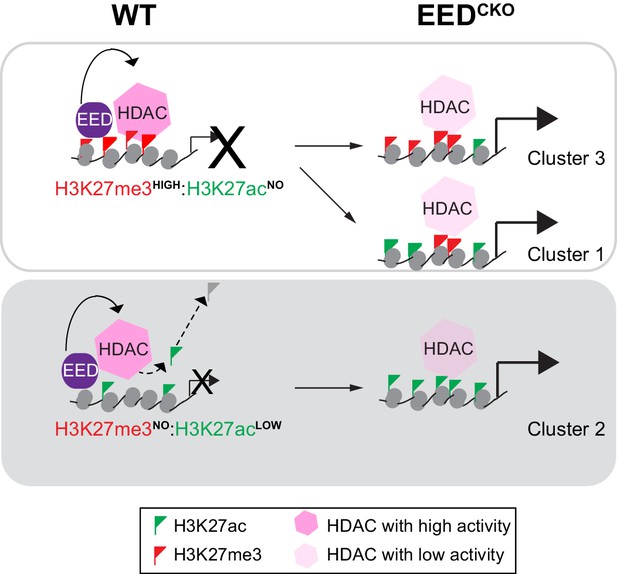

Working model delineates a non-canonical mechanism by which EED represses gene transcription.

Two mechanisms for EED repression were operative in the postnatal heart. One subset of repressed genes was occupied by EED and H3K27me3 in WT, and EED inactivation reduced H3K27me3 in association with gain of H3K27ac. Upregulation of these genes in EedCKO could be due to a combination of loss of H3K27me3 (canonical mechanism). Loss of EED itself with subsequent gain in H3K27ac might also contribute to regulation of these genes. A second subset of repressed genes was also occupied by EED and H3K27me3 in WT, but H3K27me3 was not reduced by EED inactivation. While H3K27me3 may contribute to the repression of these genes in WT, their upregulation in EedCKO was not attributable to H3K27me3, which was unchanged. Rather, our data suggest that upregulation was directly due to loss of EED itself, with consequent reduction of HDAC activity and gain in H3K27ac. A third subset of genes was occupied by EED but little H3K27me3 in WT. These genes had significant H3K27ac at baseline, which was further increased by Eed inactivation. Thus, these genes may represent a set ‘poised’ for activation; in WT EED occupancy represses these genes by collaborating with HDAC to limit gene activity. EED inactivation reduces HDAC activity, resulting in H3K27ac accumulation and gene upregulation.

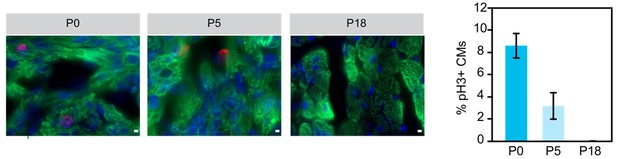

Examination of cariomyocyte proliferation rate in neonatal heart.

Immunostaining and quantification of phosphorylated histone H3 (pH2; red) as a marker for M-phase in hearts at P0, P5 and P18 cardiomyocytes (TNN13, green). Scale bar = 20 μm.

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Tables for differential peaks for H3K27me3 and H3K27ac, and differentially expressed genes in WT and CKO.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.24570.016

-

Supplementary file 2

The list of siRNAs, antibodies information and PCR primers.

(A) The sequence of the TriFECTa Dicer-Substrate siRNAs (DsiRNAs). (B) Antibodies information. (C) The list of PCR primers.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.24570.017

-

Supplementary file 3

The list of next-generation sequencing data.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.24570.018