Na+ influx via Orai1 inhibits intracellular ATP-induced mTORC2 signaling to disrupt CD4 T cell gene expression and differentiation

Figures

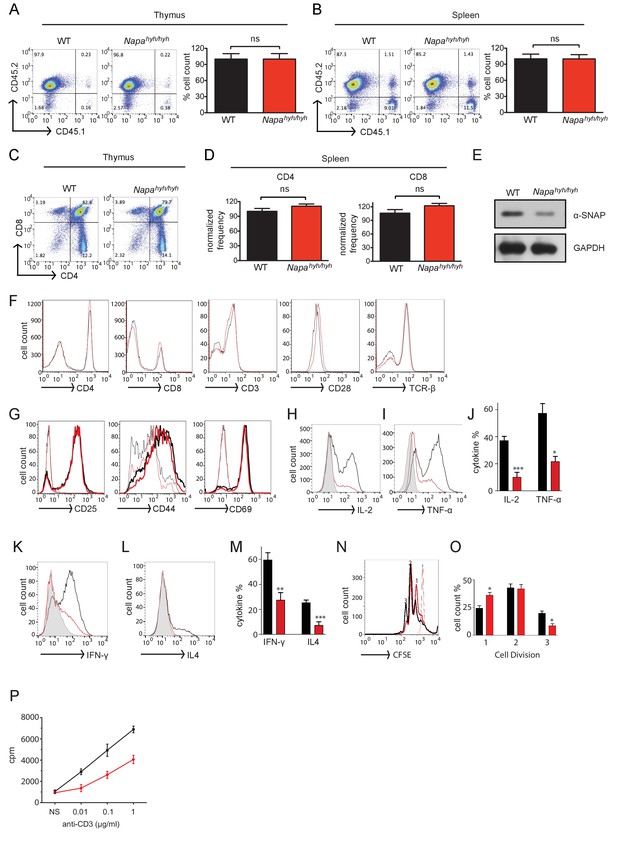

Napahyh/hyh mice harbor severe defects in the production of CD4 T cell effector cytokines.

(A and B) Representative FACS profile showing the reconstitution efficiency and average cell yields from the thymus (A) and spleen (B) of WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) fetal liver chimeric mice. (n = 25). (C and D) Representative FACS profile showing the percentage of CD4+, CD8+ single and double positive thymocytes in CD45.2+ gated cells from WT and Napahyh/hyh chimera thymus (C) and spleen (D). (n = 10). (E) Representative Western blot for α-SNAP in whole cell lysates prepared from WT and Napahyh/hyh lymph node cells. (n > 5). (F) FACS profiles showing surface staining of WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) spleen cells with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD3, anti-CD28 and anti-TCRβ antibodies respectively. (n = 5). (G) FACS profiles of resting (thin lines) and receptor stimulated (thick lines); WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells stained for various activation markers. (n = 3). (H–J) FACS profiles showing intracellular staining for IL-2 (H,J) and TNF-α (I,J) in WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells 6 hr post-stimulation. Grey peak shows unstimulated control. (n = 5 repeats from five chimeras each). (K–M) FACS profiles showing intracellular cytokine staining for Th1 (K,M) and Th2 (L,M) signature cytokines in polarized WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T lymphocytes. Grey peak shows undifferentiated control. (n = 3). (N,O) CFSE dilution profiles (N) and their quantifications (O), showing proliferation of WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells in response to plate bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Light traces show unstimulated control. (n = 3). (P) Representative plot showing proliferation of WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) splenocytes in response to soluble anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, estimated using 3H thymidine incorporation. (n = 3). (See also Figure 1—figure supplement 1).

Bar plots showing the average MFIs of the intracellular staining for T-bet and GATA-3 in Th1 and Th2 differentiated WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells, respectively. (n = 3).

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25155.003

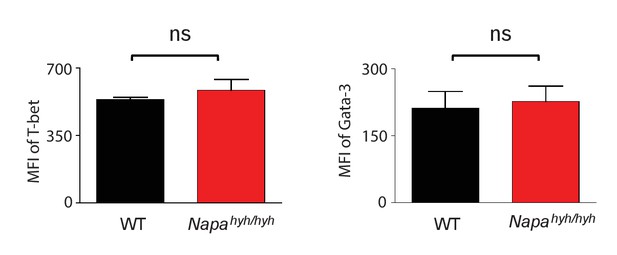

Napahyh/hyh mice harbor significant defects in the differentiation of Foxp3 regulatory T cells in vivo and in vitro.

(A) Representative FACS profiles and dot plot showing the percentage of Foxp3+CD25+ cells in the CD4+CD45.2+ population from WT and Napahyh/hyh chimera thymii. (n = 3 with 2 chimeras/experiment). (B) Dot plot showing the percentage of WT and Napahyh/hyh Foxp3+ cells in mixed chimera thymii. (n = 4 with 2–3 chimeras/experiment). p value from paired student’s t-test. (C) Dot plots showing the percentage of WT and Napahyh/hyh Foxp3+ cells in blood, spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN). (n = 4 with 2–3 chimeras/experiment). (D) Representative FACS profile and dot plots showing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of surface expression of CD44 on WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) Foxp3+ cells from various lymphoid tissues of mixed chimeras. (n = 4 with 2 chimeras/experiment). (E) FACS profile and dot plot showing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the surface expression of GITR on WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) Foxp3+ cells from spleen. (n = 3). (F) Dot plot showing the percentage of WT and Napahyh/hyh Foxp3+ cells in the lamina propria CD4 T cells isolated from mixed chimeras. (n = 3 with 2 chimeras/experiment). (G) Dot plot showing the normalized percentage of WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) Foxp3+ cells in in vitro-differentiated CD4 T cells. (n = 7). p value from paired student’s t test. (See also Figure 2—source data 1 and 2).

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Thymic Foxp3 Tregs in WT and Napahyh/hyh chimeras.

Single cell suspensions were prepared from WT and Napahyh/hyh fetal liver chimerathymii, counted and then stained for Foxp3, CD25, CD4, and CD45.2 as described in Figure 2A. The absolute numbers and percentages of Foxp3+CD25+ cells were then calculated in CD4 and CD45.2 double positive cells.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25155.005

-

Figure 2—source data 2

Foxp3 iTregs in WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cell cultures.

WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells were purified from the spleen and lymph nodes of chimeras and differentiated into Foxp3+ cells in vitro. Shown here are the absolute numbers and percentages of Foxp3 cells obtained from Figure 2G.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25155.006

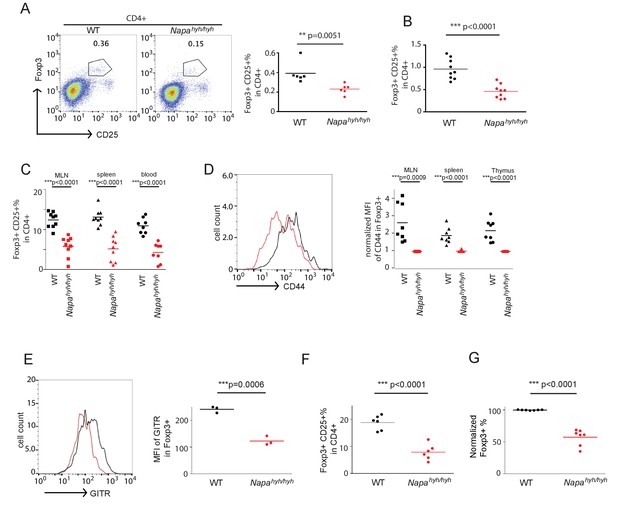

Orai1-mediated sodium influx inhibits Foxp3 iTreg differentiation by disrupting NFκB activation in Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells.

(A–C) Representative Fura-2 profiles showing real-time change in average cytosolic calcium levels in WT (black) or Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody (A and B) (n = 5 with~50 to 100 cells per experiment) or thapsigargin (TG) (C) (n = 3 with~50 to 100 cells per experiment). Percent SOCE was calculated by normalizing average WT response to 100 and then calculating the % response of Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells. (D and E) Average SBFI profiles showing real-time change in [Na]i of WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody (D) (n = 5 with~50 to 100 cells per experiment) or TG (E) (n = 1 with~50 to 100 cells per experiment). (F) Average SBFI profiles of anti-CD3-stimulated WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells treated with scramble (scr) RNAi (red) or Orai1 RNAi (blue); (magenta) anti-CD3-stimulated Napahyh/hyh T cells where [Na]e was replaced with NMDG. (n = 1 with~50 to 100 cells per experiment). (G) SBFI profiles of WT CD4 T cells, treated with Monensin (red) or untreated (black). (n = 1 with~50 to 100 cells per experiment). (H,I) Western blot for cytosolic and nuclear NFAT1 and NFκB p65 (H) or c-Rel (I) in receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells. (n = 4). (J,K) Western blot for total and phospho-Lck, ZAP-70 and PLC- γ (J) and total and phospho-Erk1/2, p38 and Jnk (K) in receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cell WCLs. (n = 3). (L) Representative Fura-2 profiles showing real-time change in average cytosolic calcium levels in scr (black) or Orai1 RNAi treated (red) CD4 T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody. (n = 2 with~50 to 100 cells per experiment). (M,N) Western blot for cytosolic and nuclear NFAT (M) and NFκB p65 (N) in receptor-stimulated scr or Orai1 RNAi (Orai1) treated WT CD4 T cells. (O) Representative dot plot showing the normalized percentage of Foxp3+ cells in scr (black) and Orai1 RNAi treated (red) CD4 T cells differentiated in vitro. (n = 3), p value from paired student’s t-test. (P) FACS profiles showing intracellular IL-2 expression in WT CD4 T cells, receptor-stimulated in the presence (red) or absence (black) of monensin. (n = 2). (Q,R) Western blot for nuclear NFAT1 (Q) and NFκB p65 (R) in receptor stimulated WT CD4 T cells with or without monensin. (n = 2). (S) Bar plot showing % Foxp3+ cells differentiated in vitro, in the absence or presence of different doses of monensin. (n = 3).

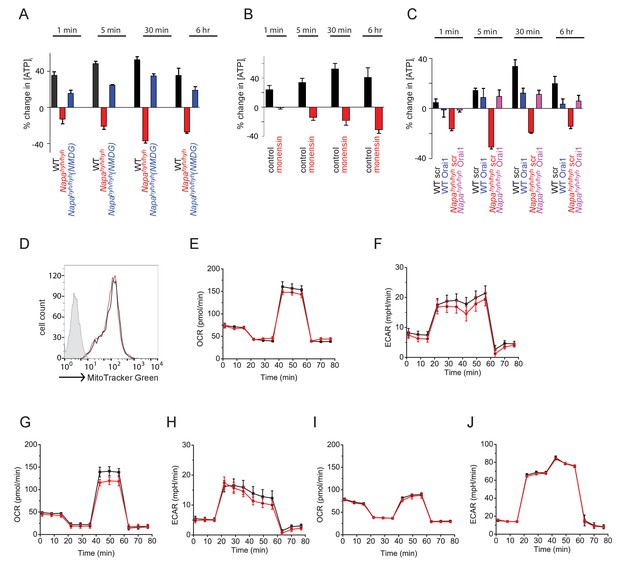

TCR-induced non-specific sodium influx depletes [ATP]i in Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells.

(A) Percent change in intracellular ATP levels [ATP]i in anti-CD3-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells, measured at different times post-stimulation. (n = 6). (B) Percent change in [ATP]i in WT CD4 T cells, stimulated with anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of Monensin. (n = 2). (C) Percent change in [ATP]i in anti-CD3-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells, treated with scramble (scr) or Orai1 RNAi (Orai1). (n = 2). (D) FACS profiles of WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells stained with Mitotracker green. (n = 2). (E–J) OCR and ECAR profiles of naive (E,F), TCR receptor stimulated for 6 hr (G,H), or TH0 (I,J) WT (black) and Napahyh/hyh (red) CD4 T cells. (n = 2 each).

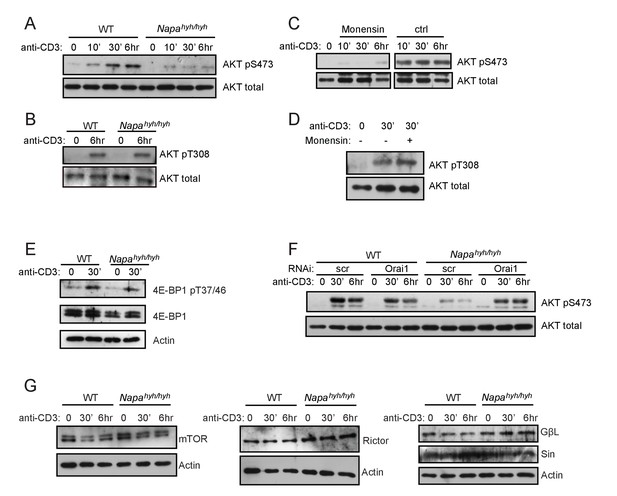

Depletion of [ATP]i inhibits mTORC2 activation in Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells.

(A,B) Western blot for total and pS473 (A) or pT308 (B) phospho-AKT in receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cell WCLs at different times post-activation. (n = 3). (C,D) Western blot for total and pS473 phospho-AKT (C) or pT308 phospho-AKT (D) in WT CD4 T cell receptor stimulated in the presence or absence of monensin. (n = 2). (E) Western blot for total and phospho- pT37/46 4E-BP1 in receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cell WCLs. (F) Western blot for total and pS473 phospho-AKT in WCLs of receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells, treated with scramble (scr) or Orai1 RNAi (Orai1). (n = 2). (G) Western blot for mTORC2 complex proteins in the WCLs of receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells. (n = 2).

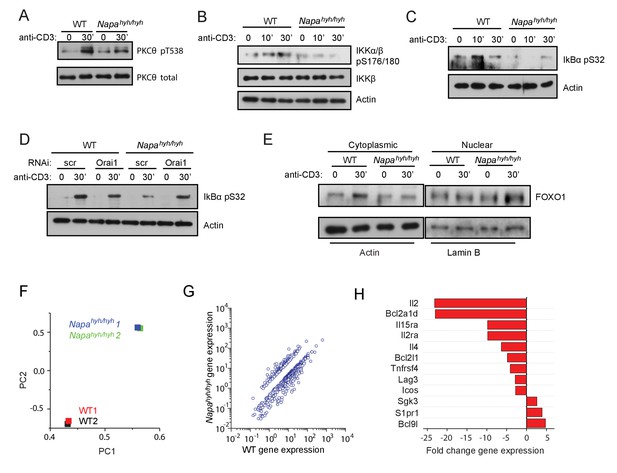

mTORC2 regulates NFκB activation via multiple signaling intermediates in Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells.

(A–C) Western blots for total and pT538 phospho-PKC-θ (A), phospho-IKKβ (B) and phospho-IκB-α (C) in WCLs of receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells. (n = 2). (D) Western blot for total and phospho-IκB-α in WCLs of receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells, treated with scr or Orai1 RNAi. (E) Western blot for cytosolic and nuclear FOXO-1 in receptor-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells. (n = 3). (F) Principal component analysis (PCA) on gene expression data from TCR-stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cell RNA. (n = 2 from 2 independent chimeras each). (G) Scatter plot showing the normalized means of gene expression values (RPKM) in Napahyh/hyh and WT CD4 T cells after filtering for genes as described in Materials and methods. (H) Bar plot showing fold change in the expression of a few representative genes between WT and Napahyh/hyh samples from (F,G) (See also Figure 6—source data 1).

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Pathways defective in receptor stimulated Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells.

Gene expression data from Figure 6G were subjected to pathway analysis and top 50 pathways that met the criteria described in Materials and methods are shown.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25155.011

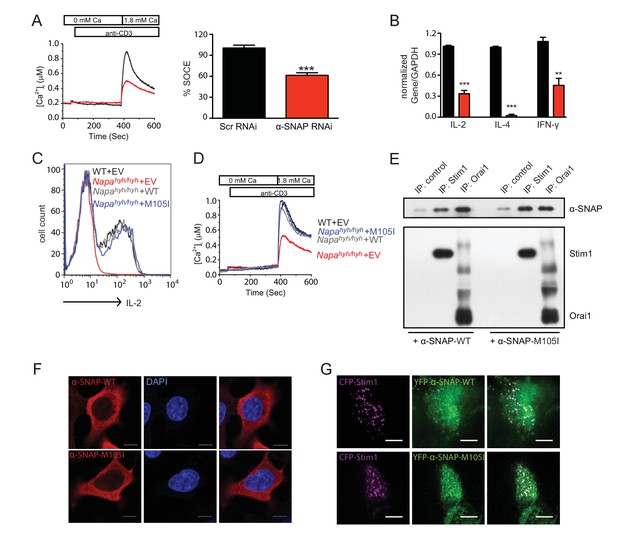

Ectopic expression of α-SNAP can restore defects in Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells.

(A) Average cytosolic calcium levels, measured using FURA 2AM, in scr (black) and α-SNAP RNAi (red)-treated cells stimulated with anti-CD3 antibody to measure SOCE. (n = 3 with ~50 to 100 cells per experiment). (B) Quantitative PCR to estimate the expression of key effector cytokines in scr (black) and α-SNAP RNAi (red)-treated Th0 cells. (n = 2 repeats; samples from 3 repeats of RNAi). (C) Representative FACS profiles showing intracellular IL-2 staining in WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells reconstituted with EV, WT or M105I α-SNAP. (n = 3). (D) Average cytosolic calcium levels, measured using FURA 2AM, in anti-CD3- stimulated WT and Napahyh/hyh CD4 T cells expressing empty vector (EV), WT or M105I α-SNAP. (n = 2 with ~50 to 200 cells each). (E) Western blot showing in vitro binding of WT and M105I α-SNAP to Stim1 and Orai1. (n = 2). (F) Confocal images of HEK293 cells expressing WT or M105I α-SNAP and stained with anti-α-SNAP antibody and DAPI (Scale bar 10 μm). (n = 2; 5 to 6 cells/ per group/ experiment). (G) TIRF images of store-depleted HEK 293 cells co-expressing CFP-Stim1 and YFP-tagged WT or M105I α-SNAP. (Scale bar 10 μm). (n = 2 with 5 to 6 cells/ per group/ experiment).

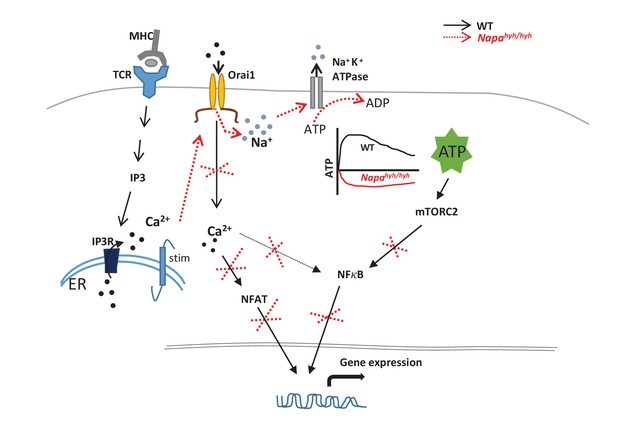

Summary of signaling nodes affected by TCR induced non-specific sodium influx.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25155.013Additional files

-

Source data 1

Antibodies used in this paper.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.25155.014