Firefly genomes illuminate parallel origins of bioluminescence in beetles

Abstract

Fireflies and their luminous courtships have inspired centuries of scientific study. Today firefly luciferase is widely used in biotechnology, but the evolutionary origin of bioluminescence within beetles remains unclear. To shed light on this long-standing question, we sequenced the genomes of two firefly species that diverged over 100 million-years-ago: the North American Photinus pyralis and Japanese Aquatica lateralis. To compare bioluminescent origins, we also sequenced the genome of a related click beetle, the Caribbean Ignelater luminosus, with bioluminescent biochemistry near-identical to fireflies, but anatomically unique light organs, suggesting the intriguing hypothesis of parallel gains of bioluminescence. Our analyses support independent gains of bioluminescence in fireflies and click beetles, and provide new insights into the genes, chemical defenses, and symbionts that evolved alongside their luminous lifestyle.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.001eLife digest

Glowing fireflies dancing in the dark are one of the most enchanting sights of a warm summer night. Their light signals are ‘love messages’ that help the insects find a mate – yet, they also warn a potential predator that these beetles have powerful chemical defenses. The light comes from a specialized organ of the firefly where a small molecule, luciferin, is broken down by the enzyme luciferase.

Fireflies are an ancient group, with the common ancestor of the two main lineages originating over 100 million years ago. But fireflies are not the only insects that produce light: certain click beetles are also bioluminescent.

Fireflies and click beetles are closely related, and they both use identical luciferin and similar luciferases to create light. This would suggest that bioluminescence was already present in the common ancestor of the two families. However, the specialized organs in which the chemical reactions take place are entirely different, which would indicate that the ability to produce light arose independently in each group.

Here, Fallon, Lower et al. try to resolve this discrepancy and to find out how many times bioluminescence evolved in beetles. This required using cutting-edge DNA sequencing to carefully piece together the genomes of two species of fireflies (Photinus pyralis and Aquatica lateralis) and one species of click beetle (Ignelater luminosus). The genetic analysis revealed that, in all species, the genes for luciferases were very similar to the genetic sequences around them, which code for proteins that break down fat. This indicates that the ancestral luciferase arose from one of these metabolic genes getting duplicated, and then one of the copies evolving a new role.

However, the genes for luciferase were very different between the fireflies and the click beetles. Further analyses suggested that bioluminescence evolved at least twice: once in an ancestor of fireflies, and once in the ancestor of the bioluminescent click beetles.

More results came from the reconstituted genomes. For example, Fallon, Lower et al. identified the genes ‘turned on’ in the bioluminescent organ of the fireflies. This made it possible to list genes that may be involved in creating luciferin, and enable flies to grow brightly for long periods. In addition, the genetic information yielded sequences from bacteria that likely live inside firefly cells, and which may participate in the light-making process or the production of potent chemical defenses.

Better genetic knowledge of beetle bioluminescence could bring new advances for both insects and humans. It may help researchers find and design better light-emitting molecules useful to track and quantify proteins of interest in a cell. Ultimately, it would allow a detailed understanding of firefly populations around the world, which could contribute to firefly ecotourism and help to protect these glowing insects from increasing environmental threats.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.002Introduction

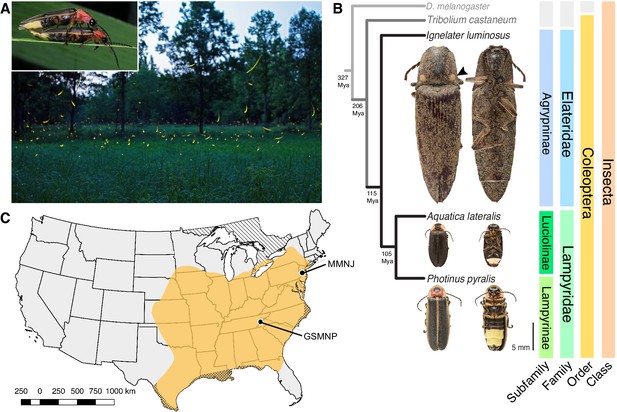

Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) represent the best-studied case of bioluminescence. The coded language of their luminous courtship displays (Figure 1A; Video 1) has been long studied for its role in mate recognition (Lloyd, 1966; Lewis and Cratsley, 2008; Stanger-Hall and Lloyd, 2015), while non-adult bioluminescence is likely a warning signal of their unpalatable chemical defenses (De Cock and Matthysen, 1999), such as the cardiotoxic lucibufagins of Photinus fireflies (Meinwald et al., 1979). The biochemical understanding of firefly luminescence: an ATP, Mg2+, and O2-dependent luciferase-mediated oxidation of the substrate luciferin (Shimomura, 2012), along with the cloning of the luciferase gene (de Wet et al., 1985; Ow et al., 1986), led to the widespread use of luciferase as a reporter with unique applications in biomedical research and industry (Fraga, 2008). With >2000 species globally, fireflies are undoubtedly the most culturally appreciated bioluminescent group, yet there are at least three other beetle families with bioluminescent species: click beetles (Elateridae), American railroad worms (Phengodidae) and Asian starworms (Rhagophthalmidae) (Martin et al., 2017). These four closely related families (superfamily Elateroidea) have homologous luciferases and structurally identical luciferins (Shimomura, 2012), implying a single origin of beetle bioluminescence. However, as Darwin recognized in his ‘Difficulties on Theory’ (Darwin, 1872), the light organs amongst the luminous beetle families are clearly distinct (Figure 1B), implying independent origins. Thus, whether beetle bioluminescence is derived from a single or multiple origin(s) remains unresolved.

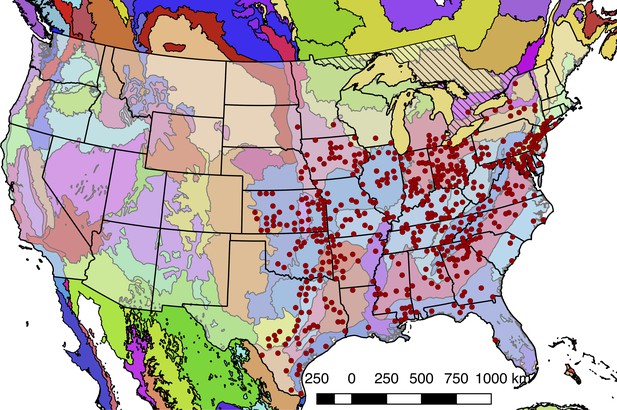

Geographic and phylogenetic context of the Big Dipper firefly, Photinus pyralis.

(A) P. pyralis males emitting their characteristic swooping ‘J’ patrol flashes over a field in Homer Lake, Illinois. Females cue in on these species-specific flash patterns and respond with their own species-specific flash (Lloyd, 1966). Photo credit: Alex Wild. Inset: male and female P. pyralis in early stages of mating. Photo credit: Terry Priest. (B) Cladogram depicting the hypothetical phylogenetic relationship between P. pyralis and related bioluminescent and non-bioluminescent taxa with Tribolium castaneum and Drosophila melanogaster as outgroups. Numbers at nodes give approximate dates of divergence in millions of years ago (mya) (Misof et al., 2014; Mckenna et al., 2015). Right: Dorsal and ventral photos of adult male specimens. Note the well-developed ventral light organs on the true abdominal segments 6 and 7 of P. pyralis and A. lateralis. In contrast, the luminescent click beetle, I. luminosus, has paired dorsal light organs at the base of its prothorax (arrowhead) and a lantern on the anterior surface of the ventral abdomen (not visible). (C) Empirical range of P. pyralis in North America, extrapolated from 541 reported sightings (Appendix 1.2). Collection sites of individuals used for genome assembly are denoted with circles and location codes. Cross hatches represent areas which likely have P. pyralis, but were not sampled. Diagonal hashes represent Ontario, Canada.

A Photinus pyralis courtship dialogue.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.004To address this long-standing question, we sequenced and analyzed the genomes of three bioluminescent beetle species. To represent the fireflies, we sequenced the widespread North American ‘Big Dipper Firefly’, P. pyralis (Figure 1A,C) and the Japanese ‘Heike-botaru’ firefly Aquatica lateralis (Figure 1B). P. pyralis was used in classic studies of firefly bioluminescent biochemistry (Bitler and McElroy, 1957) and the cloning of luciferase (de Wet et al., 1985), while A. lateralis, a species with specialized aquatic larvae, is one of the few fireflies that can be reliably cultured in the laboratory (Oba et al., 2013a). These two fireflies represent the two major firefly subfamilies, Lampyrinae and Luciolinae, which diverged from a common ancestor over 100 Mya (Figure 1B) (Misof et al., 2014; Mckenna et al., 2015). To facilitate evolutionary comparisons, we also sequenced the ‘Cucubano’, Ignelater luminosus (Figure 1B), a Caribbean bioluminescent click beetle, and member of the ‘Pyrophorus’ used by Raphaël Dubois (1849-1929) to first establish the enzymatic basis of bioluminescence in the late 1800s (Dubois, 1885; Dubois, 1886). Comparative analyses of the genomes of these three species allowed us to reconstruct the origin(s) and evolution of beetle bioluminescence.

Results

Sequencing and assembly of firefly and click-beetle genomes

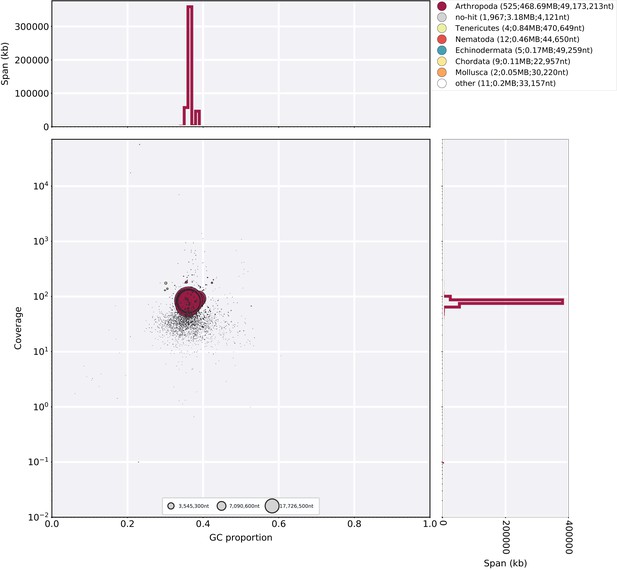

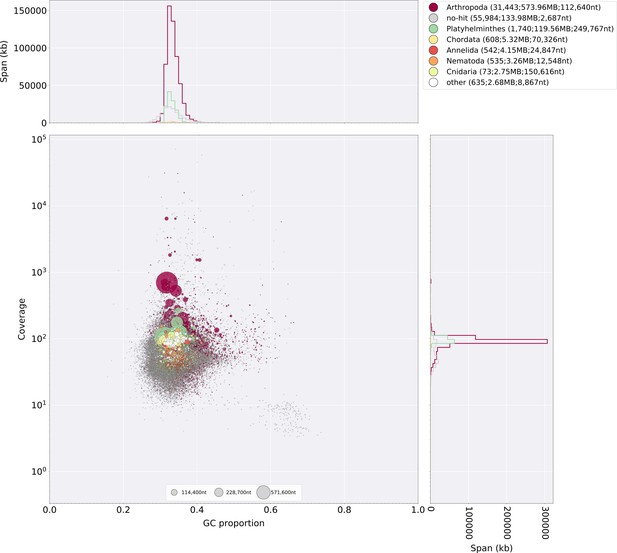

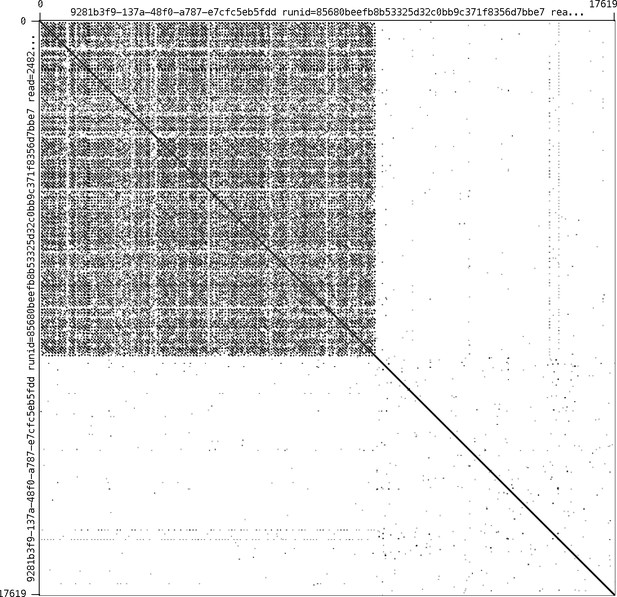

Photinus pyralis adult males were collected from the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA (GSMNP) and Mercer Meadows New Jersey, USA (MMNJ) (Figure 1C), and sequenced using short-insert, mate-pair, Hi-C, and long-read Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) approaches (Appendix 4—table 1). These datasets were combined in a MaSuRCA (Zimin et al., 2013) hybrid genome assembly (Appendix 1.5). The Aquatica lateralis genome was derived from an ALL-PATHs (Butler et al., 2008) assembly of short insert and mate-pair reads from a single adult female from a laboratory-reared population, whose lineage, dubbed ‘Ikeya-Y90’, was first collected 25 years ago from a now extinct population in Yokohama, Japan (Appendix 2.5). A single Ignelater luminosus adult male, collected in Mayagüez Puerto Rico, USA, was used to produce a high-coverage Supernova (Weisenfeld et al., 2017) linked-read draft genome (Appendix 3.5), which was further manually scaffolded using low-coverage long-read Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing (Appendix 3.5.4).

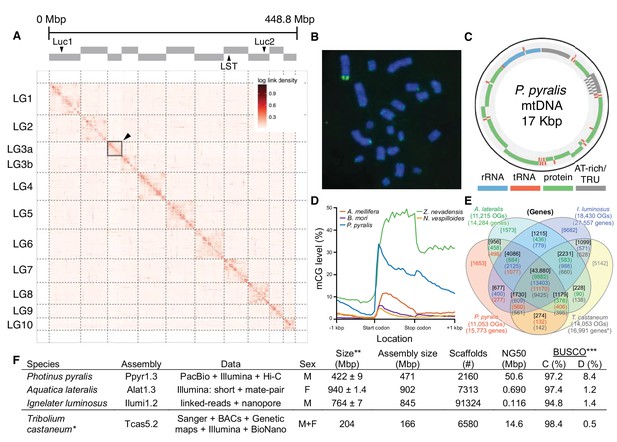

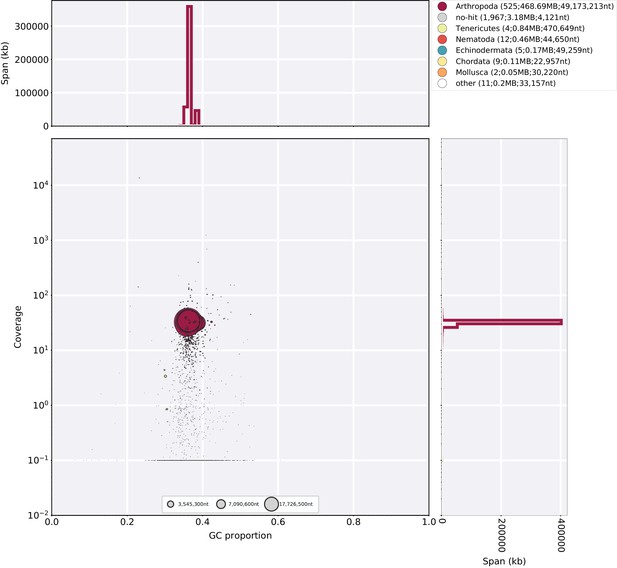

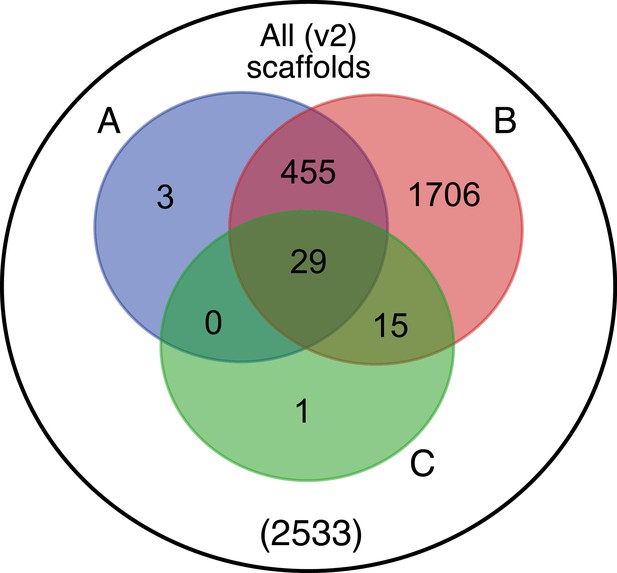

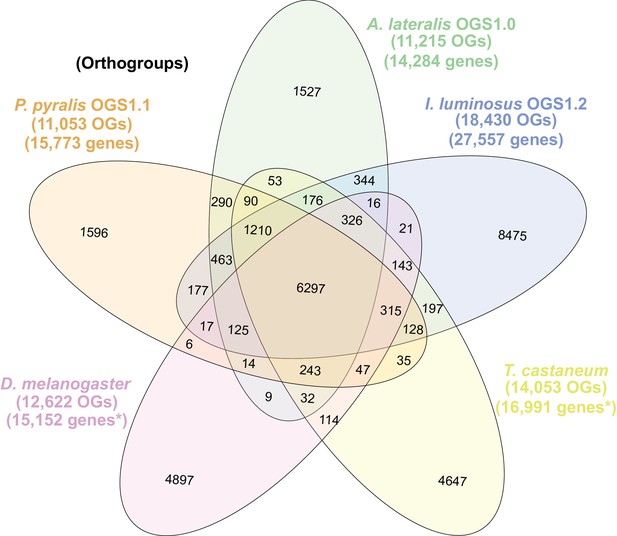

The gene completeness and contiguity statistics of our P. pyralis (Ppyr1.3) and A. lateralis (Alat1.3) genome assemblies are comparable to the genome of the model beetle Tribolium castaneum (Figure 2F; Appendix 4.1). The I. luminosus genome assembly (Ilumi1.2) is less complete, but is comparable to other published insect genomes (Figure 2F; Appendix 4.1). Protein-coding genesets for our study species were produced via an EvidenceModeler-mediated combination of homology alignments, ab initio predictions, and de novo and reference-guided RNA-seq assemblies followed by manual gene curation for gene families of interest (Appendix 1.10; 2.8; 3.8). These coding gene annotation sets for P. pyralis, A. lateralis, and I. luminosus are comprised of 15,773, 14,285, and 27,557 genes containing 94.2%, 90.0%, and 91.8% of the Endopterygota Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCOs) (Simão et al., 2015), respectively. Protein clustering via predicted orthology indicated 77% of genes were found in orthogroups with at least one other species (Figure 2E; Appendix 4—figure 1). We found the greatest orthogroup overlap between the P. pyralis and A. lateralis genesets, as expected given the more recent phylogenetic divergence of these species. Remaining redundancy in the P. pyralis assembly and annotation, as indicated by duplicates of the BUSCOs and the assembly size (Figure 2F; Appendix 4—table 2) is likely due to the heterozygosity of the outbred input libraries (Appendix 1). The higher BUSCO completeness of the assemblies as compared to the genesets (Appendix 4—table 3), suggests that future manual curation efforts will lead to improved annotation completeness.

Photinus pyralis genome assembly and analysis.

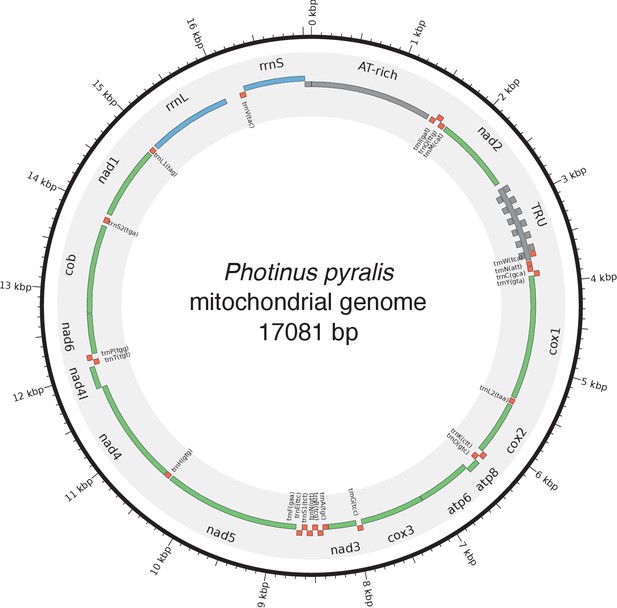

(A) Assembled Ppyr1.3 linkage groups with annotation of the location of known luminescence-related genes, combined with Hi-C linkage density maps. Linkage group 3a (box with black arrow) corresponds to the X chromosome (Appendix 1.6.4.1). (B) Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on mitotic chromosomes of a P. pyralis larvae. The telomeric repeats TTAGG (green) localize to the ends of chromosomes stained with DAPI (blue). 20 paired chromosomes indicates that this individual was an XX female (Appendix 1.13). (C) Genome schematic of P. pyralis mitochondrial genome (mtDNA). Like other firefly mtDNAs, it has a tandem repetitive unit (TRU) (Appendix 1.8). (D) mCG is enriched across gene bodies of P. pyralis and shows methylation levels that are at least two times higher than other holometabolous insects (Appendix 1.12). (E) Orthogroup (OGs) clustering analysis of genes with Orthofinder (Emms and Kelly, 2015) shows a high degree of overlap of the P. pyralis, A. lateralis, and I. luminosus genesets with the geneset of Tribolium castaneum. Numbers within curved brackets (colored by species) represent gene count from specific species within the shared orthogroups. Numbers with square brackets (black color) represent total gene count amongst shared orthogroups. OGs = orthogroups, *=Not fully filtered to single isoform per gene. See Appendix 4.2.1 for more detail. Intermediate scripts and species-specific overlaps are available as Figure 2—source data 1. (F) Assembly statistics for presented genomes. *=Tribolium castaneum model beetle genome assembly (Tribolium Genome Sequencing Consortium et al., 2008) **=Genome size estimated by FC: flow cytometry. P. pyralis n = 5 females (SEM) I. luminosus n = 5 males (SEM), A. lateralis n = 3 technical-replicates of one female (SD). ***=Complete (C), and Duplicated (D), percentages for the Endopterygota BUSCO (Simão et al., 2015) profile (Appendix 1.4, 2.4, 3.4, 4.1).

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Figure 2E. Orthogroup clustering analysis.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.006

-

Figure 2—source data 2

Excel file of Figure 2F table.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.007

To enable the characterization of long-range genetic structure, we super-scaffolded the P. pyralis genome assembly into 11 pseudo-chromosomal linkage groups using a Hi-C proximity-ligation linkage approach (Figure 2A; Appendix 1.5.3). These linkage groups contain 95% of the assembly (448.8 Mbp). Linkage group LG3a corresponds to the X-chromosome based on expected adult XO male read coverage and gene content (Appendix 1.6.4.1) and its size (22.2 Mbp) is comparable to the expected X-chromosome size based on sex-specific genome size estimates using flow cytometry (~26 Mbp) (Lower et al., 2017). Homologs to T. castaneum X-chromosome genes were enriched on LG3a over every other linkage group, suggesting that the X-chromosomes of these distantly related beetles are homologous, and that their content has been reasonably conserved for >200 MY (Appendix 1.6.4.1) (Mckenna et al., 2015). We hypothesized that the P. pyralis orthologs of known bioluminescence genes, including the canonical luciferase Luc1 (de Wet et al., 1985) and the specialized luciferin sulfotransferase LST (Fallon et al., 2016), would be located on the same linkage group to facilitate chromosomal looping and enhancer assisted co-expression within the light organ. We, however, found these genes on separate linkage groups (Figure 2A).

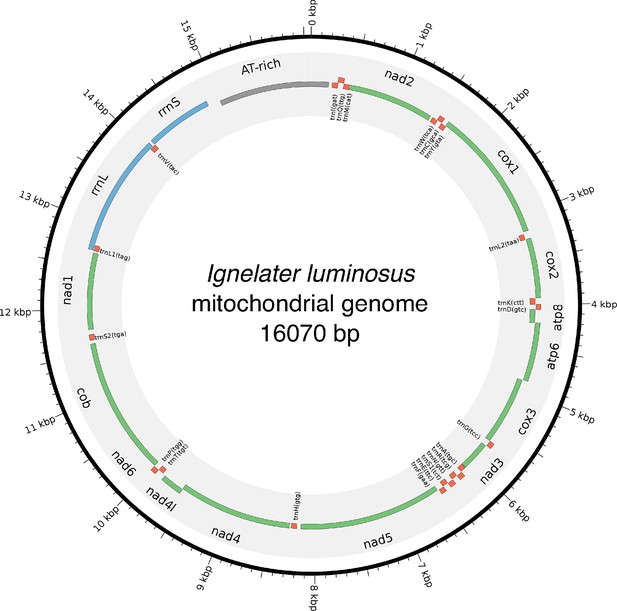

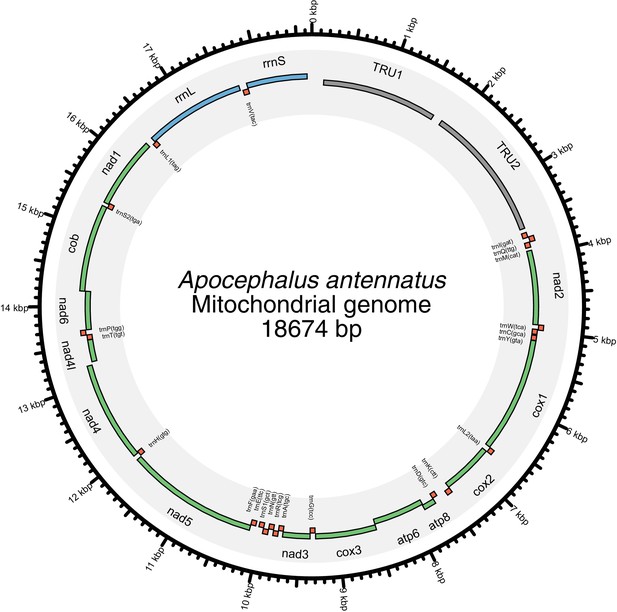

In addition to nuclear genome assembly and coding gene annotation, we also assembled the complete mitochondrial genomes (mtDNA) of P. pyralis (Figure 2C; Appendix 1.8) and I. luminosus (Appendix 3.10), while the mtDNA sequence of A. lateralis was recently published (Maeda et al., 2017). These mtDNA assemblies show high conservation of gene content and synteny, with the exception of the variable ~1 Kbp tandem repeat unit (TRU) found in the firefly mtDNAs.

As repetitive elements are common participants and drivers of genome evolution (Feschotte and Pritham, 2007), we next sought to characterize the repeat content of our genome assemblies. Overall, 42.6%, 19.8%, and 34.1% of the P. pyralis, A. lateralis, and I. luminosus assemblies were found to be repetitive, respectively (Appendix 1.11; 2.9; 3.9). Of these repeats 66.7%, 39.4%, and 55% could not be classified as any known repetitive sequence, respectively. Helitrons, DNA transposons that transpose through rolling circle replication (Kapitonov and Jurka, 2001), are among the most abundant individual repeat elements in the P. pyralis assembly. Via in situ hybridization, we identified that P. pyralis chromosomes have canonical telomeres with telomeric repeats (TTAGG) (Figure 2B; Appendix 1.13).

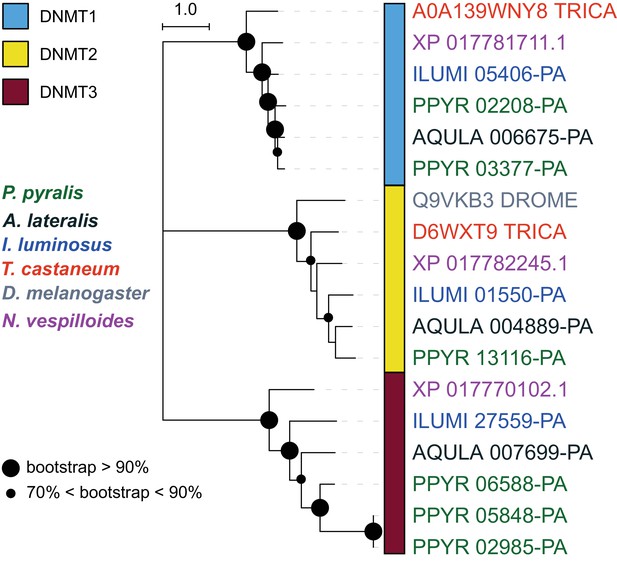

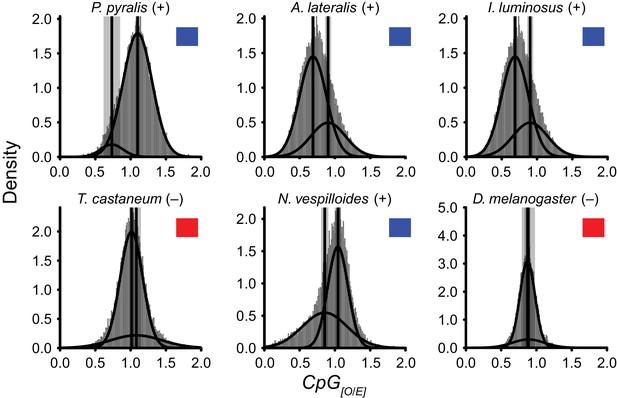

DNA methylation is common in eukaryotes, but varies in degree across insects, especially within Coleoptera (Bewick et al., 2017). Furthermore, the functions of DNA methylation across insects remain obscure (Bewick et al., 2017; Glastad et al., 2017). To examine firefly cytosine methylation, we characterized the methylation status of P. pyralis DNA with whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS). Methylation at CpGs (mCG) was unambiguously detected at ~20% within the genic regions of P. pyralis and its methylation levels were at least twice those reported from other holometabolous insects (Figure 2D; Appendix 1.12). Molecular evolution analyses of the DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) show that direct orthologs of both DNMT1 and DNMT3 were conserved in P. pyralis, A. lateralis, and I. luminosus (Appendix 4—figure 2; Appendix 4.2.3), implying that our three study species, and inferentially likely most firefly lineages, possess mCG. Corroborating this claim, CpG[O/E] analysis of methylation indicated our three study species had DNA methylation (Appendix 4—figure 3).

The genomic context of firefly luciferase evolution

Two luciferase paralogs have been previously described in fireflies (Oba et al., 2013a; Bessho-Uehara et al., 2017). P. pyralis Luc1 was the first firefly luciferase cloned (de Wet et al., 1985), and its direct orthologs have been widely identified from other fireflies (Oba, 2014). The luciferase paralog Luc2 was previously known only from a handful of Asian taxa, including A. lateralis (Oba et al., 2013a; Bessho-Uehara et al., 2017). Previous investigations of these Asian taxa have shown that Luc1 is responsible for light production from the lanterns of adults, larvae, prepupae and pupae, whereas Luc2 is responsible for the dim glow of eggs, ovaries, prepupae and the whole pupal body (Bessho-Uehara et al., 2017). From our curated genesets (Appendix 1.10; 2.8), we unequivocally identified two firefly luciferases, Luc1 and Luc2, in both the P. pyralis and A. lateralis genomes. Our RNA-Seq data further show that in both P. pyralis and A. lateralis, Luc1 and Luc2 display expression patterns consistent with previous reports. While Luc1 is the sole luciferase expressed in the lanterns of both larvae and adults, regardless of sex, Luc2 is expressed in other tissues and stages, such as eggs (Figure 3C). Notably, Luc2 expression is detected in RNA libraries derived from adult female bodies (without head or lantern), suggesting detection of ovary expression as described in previous studies (Bessho-Uehara et al., 2017). Together, these results support that since their divergence via gene duplication prior to the divergence of Lampyrinae and Luciolinae, Luc1 and Luc2 have established different, but conserved roles in bioluminescence throughout the firefly life cycle.

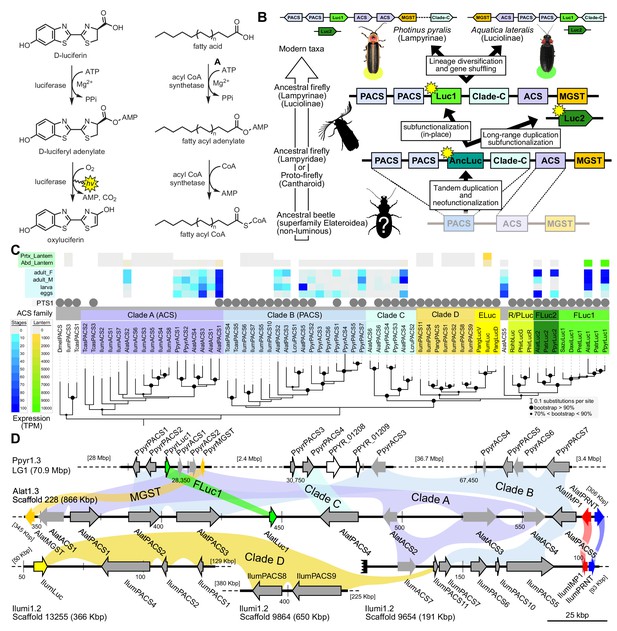

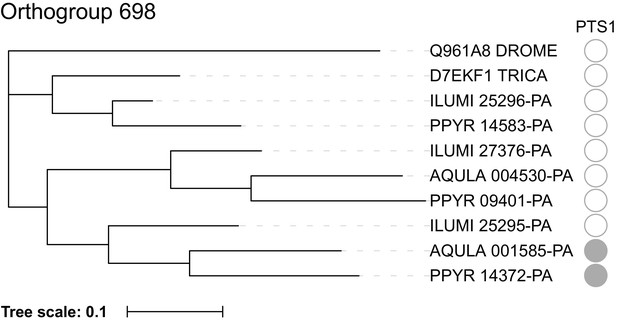

A genomic view of luciferase evolution.

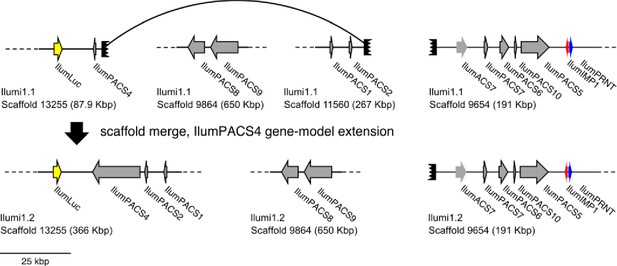

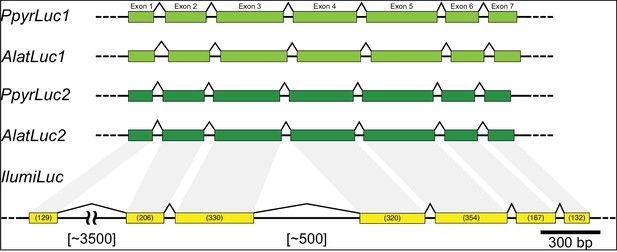

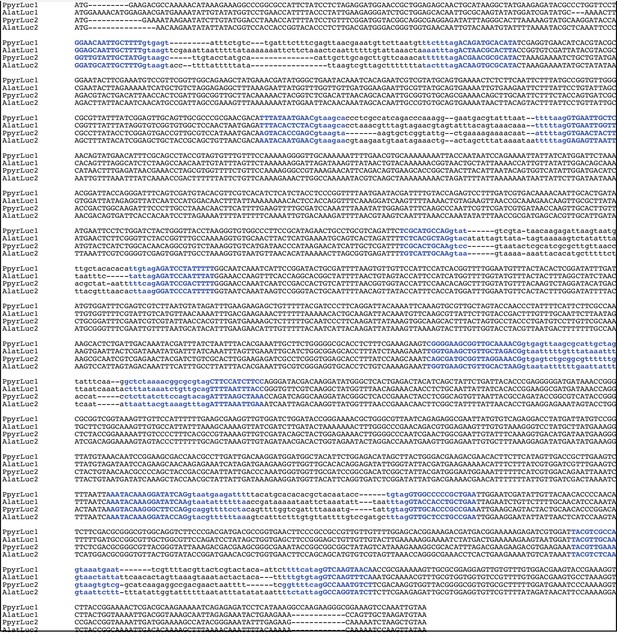

(A) The reaction scheme of firefly luciferase is related to that of fatty acyl-CoA synthetases. (B) Model for genomic evolution of firefly luciferases. Ranging from genome structures of luciferase loci in extant fireflies (top), to inferred genomic structures in ancestral species (bottom). Arrow (left) represents ascending time. Not all adjacent genes within the same clade are shown. (C) Maximum likelihood tree of luciferase homologs. Grey circles above gene names indicate the presence of peroxisomal targeting signal 1 (PTS1). Color gradients indicate the transcript per million (TPM) values of whole body in each sex/stage (grey to blue) and in the prothorax or abdominal lantern (grey to orange to green). Tree and annotation visualized using iTOL (Letunic and Bork, 2016). Prothorax and abdominal lantern expression values for I. luminosus are from whole prothorax plus head, and metathorax plus the two most anterior abdominal segments. Fluc = firefly luciferases, Eluc = elaterid luciferases, R/PLuc = rhagophthalmid/phengodid luciferases. (Appendix 4.3.2) Gene tree, gene accession numbers, annotation, and expression values are available as Figure 3—source data 1. (D) Synteny analysis of beetle luciferase homologs. Nine of the 14 A. lateralis PACS/ACS genes closely flank AlatLuc1 on scaffold 228, while 4 of the 13 P. pyralis PACS/ACS genes are close neighbors of PpyrLuc1 on LG1, with a further seven genes 2.4 Mbp and 39.1 Mbp away on the same linkage-group. Although the Luc1 loci in P. pyralis and A. lateralis are evidently derived from a common ancestor, the relative positions of the most closely related flanking PACS/ACS genes have diverged between the two species. IlumLuc was captured on a separate scaffold (Ilumi1.2_Scaffold13255) from its most most closely related PACSs (IlumPACS8, IlumPACS9) on Ilumi1.2_Scaffold9864, although three more distantly related PACS genes (IlumiPACS1, IlumiPACS2, IlumiPACS4) are co-localized with IlumLuc. In contrast, a different scaffold (Ilumi1.2_Scaffold9654) shows orthology to the firefly Luc1 locus. The full Ilumi1.2_Scaffold13255 was produced by a manual evidence-supported merge of two scaffolds (Appendix 3.5.4). Genes with a PTS1 are indicated by a dark outline, except for the genes with white interiors, which instead represent non-PACS/ACS genes without an identified homolog in the other scaffolds. Co-orthologous genes are labeled in the same color in the phylogenetic tree and are connected with corresponding color bands in synteny diagram. Genes and genomic regions are to scale (Scale bar = 25 Kbp). Gaps excluded from the figure are shown with dotted lines and are annotated with their length in square brackets. Scaffold ends are shown with rough black bars. MGST = Microsomal glutathione S-transferase, IMP = Inositol monophosphatase, PRNT = Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase. Figure produced with GenomeTools ‘sketch’ (v1.5.9) (Gremme et al., 2013). Figure production scripts available as Figure 3—source data 2.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Gene tree, gene accession numbers, annotation, and expression values for Figure 3C.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.009

-

Figure 3—source data 2

Bash scripts for Figure 3D figure production.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.010

Firefly luciferase is hypothesized to be derived from an ancestral peroxisomal fatty acyl-CoA synthetase (PACS) (Figure 3A) (Oba et al., 2003; Oba et al., 2006a). We found that, in both firefly species, Luc1 is genomically clustered with its closely related homologs, including PACSs and non-peroxisomal acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSs), enzymes which can be distinguished by the presence/absence of a C-terminal peroxisomal-targeting-signal-1 (PTS1). We also found nearby microsomal glutathione S-transferase (MGST) family genes (Figure 3D) that are directly orthologous between both species, Genome-wide phylogenetic analysis of the luciferases, PACSs and ACSs genes indicates that Luc1 and Luc2 form two orthologous groups, and that the neighboring PACS and ACS genes near Luc1 form three major clades (Figure 3C): Clade A, whose common ancestor and most extant members are ACSs, and Clades B and C whose common ancestors and most extant members are PACSs. Luc1 and Luc2 are highly conserved at the level of gene structure—both are composed of seven exons with completely conserved exon/intron boundaries (Appendix 4—figure 4; Appendix 4—figure 5), and most members of Clades A, B, and C also have seven exons. The exact syntenic and orthology relationships of the ACS and PACS genes adjacent to the Luc1 locus remains unclear, likely due to subsequent gene divergence and shuffling (Figure 3C,D).

Luc2 is located on a different linkage-group from Luc1 in P. pyralis and on a different scaffold from Luc1 in A. lateralis, consistent with the interpretation that Luc1 and Luc2 lie on different chromosomes in both firefly species. No PACS or ACS genes were found in the vicinity of Luc2 in either species. These data support that tandem gene duplication in a firefly ancestor gave rise to several ancestral PACS paralogs, one of which neofunctionalized in place to become the ancestral luciferase (AncLuc) (Figure 3B). Prior to the divergence of the firefly subfamilies Lampyrinae and Luciolinae around 100 Mya (Appendix 4.3), this AncLuc duplicated, possibly via a long-range gene duplication event (e.g. transposon mobilization), and then subfunctionalized in its transcript expression pattern to give rise to Luc2, while the original AncLuc subfunctionalized in place to give rise to Luc1 (Figure 3B). From the shared Luc gene clustering in both fireflies, we infer the structure of the pre Luc1/Luc2 duplication AncLuc locus contained one or more ACS genes (Clade A), one or more PACS genes (Clade B/C), and one or more MGST family genes (Figure 3B).

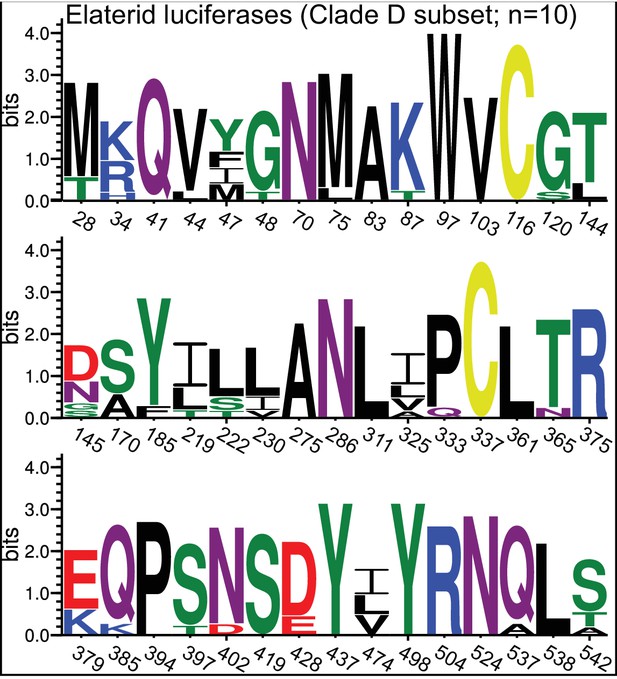

Independent origins of firefly and click beetle luciferase

To resolve the number of origins of luciferase activity, and therefore bioluminescence, between fireflies and click beetles, we first identified the luciferase of I. luminosus luciferase (IlumLuc), and compared its genomic context to the luciferases of P. pyralis and A. lateralis (Figure 3D). Unlike some other described bioluminescent Elateridae, which have separate luciferases expressed in the dorsal prothorax and ventral abdominal lanterns (Oba et al., 2010a), we identified only a single luciferase in the I. luminosus genome which was highly expressed in both of the lanterns (Figure 3C; Appendix 3.8). The exon number and exon-intron splice junctions of IlumLuc are identical to those of firefly luciferases, but unlike the firefly luciferases which have short introns less than <100 bp long, IlumLuc has two long introns (Appendix 4—figure 4). We found several PACS genes in the I. luminosus genome which were related to IlumLuc and formed a clade (Clade D) specific to the Elateridae (Figure 3C,D). IlumLuc lies on a 366 Kbp scaffold containing 18 other genes, including three related Clade D PACS genes (Scaffold 13255; Figure 3D; Figure 4); however, the Clade D genes that are most closely related to IlumLuc are found on a separate 650 Kbp scaffold (Scaffold 9864; Figure 3D). We infer that the IlumLuc locus is not orthologous to the extant firefly Luc1 locus, as IlumLuc is not physically clustered with Clade A, B or C ACS or PACS genes (Figure 3C,D). We instead identified a different scaffold in I. luminosus that is likely orthologous to the firefly Luc1 locus (Scaffold 9654; Figure 3D). This assessment is based on the presence of adjacent Clade A and B ACS and PACS genes, as well as orthologous exoribonuclease family (PRNT) and inositol monophosphatase family (IMP) genes, both of which were found adjacent to the A. lateralis Luc1 locus, but not the P. pyralis Luc1 locus (Figure 3D). Interestingly, IlumPACS11, the most early-diverging member of Clade D, was also found on Scaffold 9654 (Figure 3D). This finding is consistent with an expansion of Clade D following duplication of the IlumPACS11 syntenic ancestor to a distant site. Overall, these genomic structures are consistent with independent origins of firefly and click beetle luciferases.

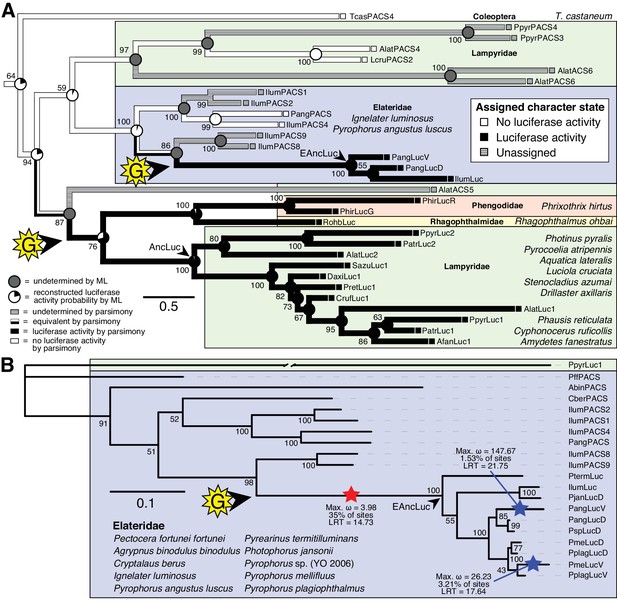

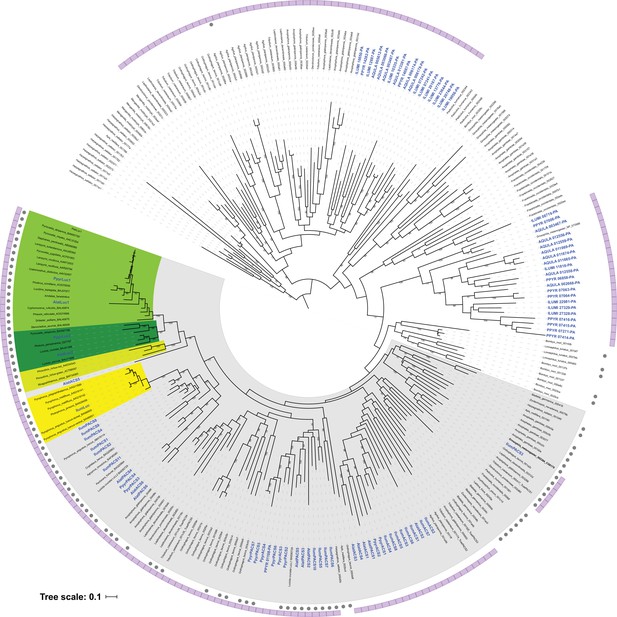

Parallel evolution of elaterid and firefly luciferase.

(A) Ancestral state reconstruction recovers at least two gains of luciferase activity in bioluminescent beetles. Luciferase activity (top right figure key; black: luciferase activity, white: no luciferase activity, shaded: undetermined) was annotated on extant firefly luciferase homologs via literature review or inference via direct orthology. The ancestral states of luciferase activity within the putative ancestral nodes were then reconstructed with an unordered parsimony framework and a maximum likelihood (ML) framework (bottom left figure key; Appendix 4.3.3). Two gains (‘G’) of luciferase activity, annotated with black arrows and yellow stars, are hypothesized. These hypothesized gains occurred once in a gene within the common ancestor of fireflies, rhagophthalmid, and phengodid beetles, and once in a gene within the common ancestor of bioluminescent elaterid beetles. Scale bar is substitutions per site. Numbers adjacent to nodes represents node support. NEXUS and newick files available as Figure 4—source data 1 (B) Molecular adaptation analysis supports independent neofunctionalization of click beetle luciferase. We tested the molecular adaptation of elaterid luciferase using the adaptive branch-site REL test for episodic diversification (aBSREL) method (Smith et al., 2015) (Appendix 4.3.4). The branch leading to the common ancestor of elaterid luciferases (red star) was one of three branches (red and blue stars) recovered with significant (p<0.01) evidence of positive selection, with 35% of sites showing strong directional selection (ω or max dN/dS = 3.98), which we interpret as signal of the initial neofunctionalization of elaterid ancestral luciferase (EAncLuc) from an ancestor without luciferase activity. As the selected branches with blue stars are red-shifted elaterid luciferases (Oba et al., 2010a; Stolz et al., 2003), they may represent the post-neofunctionalization selection of a few key sites via sexual selection of emission colors. Specific sites identified as under selection using Mixed Effect Model of Evolution (MEME) and Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood (PAML) methods are described in Appendix 4.3.4. The tree and results from the full adaptive model are shown. Branch length, with the exception of the PpyrLuc1 branch which was shortened, reflects the number of substitutions per site. Numbers adjacent to nodes represents node support. Figure was produced with iTOL (Letunic and Bork, 2016). Gene tree, metadata, and coding nucleotide multiple sequence alignment available as Figure 4—source data 2.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

NEXUS and Newick files for luciferase ancestral state reconstruction in Figure 4A.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.012

-

Figure 4—source data 2

Gene tree, metadata, and coding nucleotide multiple sequence alignment for Elaterid luciferase homolog branch selection test.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.013

We then carried out targeted molecular evolution analyses including the known beetle luciferases and their closely related homologs. Ancestral state reconstruction of luminescent activity on the gene tree using Mesquite (Maddison and Maddison, 2017) recovered two independent gains of luminescence as the most parsimonious and likely scenario: once in click beetles, and once in the common ancestor of firefly, phengodid, and rhagophthalmid beetles (Figure 4A; Appendix 4.3.3). In an independent molecular adaptation analysis utilizing the coding nucleotide sequence of the elaterid luciferases and their close homologs within Elateridae, 35% of the sites of the branch leading to the ancestral click beetle luciferase showed a statistically significant signal of episodic positive selection with dN/dS > 1 (ω or max dN/dS = 3.98) as compared to the evolution of its paralogs using the aBSREL branch-site selection test (Smith et al., 2015) (Figure 4B; Appendix 4.3.4). This implies that the common ancestor of the click beetle luciferases (EAncLuc) underwent a period of accelerated directional evolution. As the branch under selection in the molecular adaptation analysis (Figure 4B) is the same branch of luciferase activity gain via ancestral reconstruction (Figure 4A), we conclude that the identified selection signal represents the relatively recent neofunctionalization of click beetle luciferase from a non-luminous ancestral Clade D PACS gene, distinct from the more ancient neofunctionalization of firefly luciferase. Based on the constraints from our tree, we determine that this neofunctionalization of EAncLuc occured after the divergence of the elaterid subfamily Agrypninae. In contrast, we cannot determine if the original neofunctionalization of AncLuc occurred in the ancestral firefly, or at some point during the evolution of ‘cantharoid’ beetles, an unofficial group of beetles including the luminous Rhagophthalmidae, Phengodidae and Lampyridae among other non-luminous groups, but not the Elateridae (Branham and Wenzel, 2003). There is evidence for a subsequent luciferase duplication event in phengodids, but not in rhagophthalmids, that is independent of the duplication event that gave rise to Luc1 and Luc2 in fireflies (Figures 3C and 4). Altogether, our results strongly support the independent neofunctionalization of luciferase activity in click beetles and fireflies, and therefore at least two independent gains of luciferin-utilizing luminescence in beetles.

Metabolic adaptation of the firefly lantern

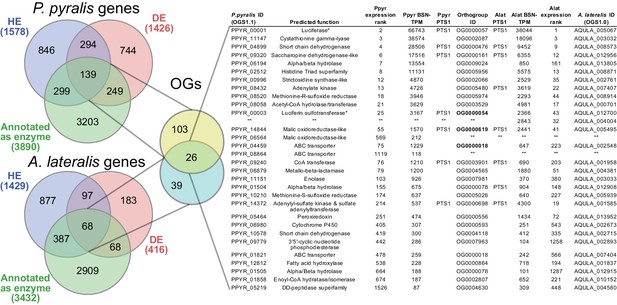

Beyond luciferase, we sought to characterize other metabolic traits which might have co-evolved in fireflies to support bioluminescence. Of particular importance, the enzymes of the de novo biosynthetic pathway for firefly luciferin remain unknown (Oba et al., 2013b). We hypothesized that bioluminescent accessory enzymes, either specialized enzymes with unique functions in luciferin metabolism or enzymes with primary metabolic functions relevant to bioluminescence, would be highly expressed (HE: 90th percentile; Appendix 4.2.2) in the adult lantern, and would be differentially expressed (DE; Appendix 4.2.2) between luminescent and non-luminescent tissues. To determine this, we performed RNA-Seq and expression analysis of the dissected P. pyralis and A. lateralis adult male lantern tissue compared with a non-luminescent tissue (Appendix 4.2.2). We identified a set of predicted orthologous enzyme-encoding genes conserved in both P. pyralis and A. lateralis that met our HE and DE criteria (Figure 5). Both luciferase and luciferin sulfotransferase (LST), a specialized enzyme recently implicated in luciferin storage in P. pyralis (Fallon et al., 2016), were recovered as candidate genes using four criteria (HE, DE, enzymes, direct orthology across species), confirming the validity of our approach. While a direct ortholog of LST is present in A. lateralis, it is absent from I. luminosus, suggesting that LST, and the presumed luciferin storage it mediates, is an exclusive ancestral firefly or cantharoid trait. This finding is consistent with previous hypotheses of the absence of LST in Elateridae (Fallon et al., 2016), and with the overall hypothesis of independent evolution of bioluminescence between the Lampyridae and Elateridae.

Comparative analyses of firefly lantern expression highlight likely metabolic adaptations to bioluminescence.

Enzymes which are highly expressed (HE), differentially expressed (DE), and annotated as enzymes via InterProScan are shown in the Venn diagrams for their respective species. Those genes in the intersection of the two sets which are within the same orthogroup (OGs) as determined by OrthoFinder are shown in the table. Many-to-one orthology relationships are represented by bold orthogroups and blank cells. See Appendix 4.2.2 for more detail. *=genes of previously described function. Underlying expression quantification and Venn analysis available on FigShare: (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.5715151)

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Table of Figure 5 highly expressed, differentially expressed, orthogroup overlapped genes.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.015

Moreover, we identified several additional enzyme-encoding HE and DE lantern genes that are likely important in firefly lantern physiology (Figure 5). For instance, adenylate kinase likely plays a critical role in efficient recycling of AMP post-luminescence, and cystathionine gamma-lyase supports a key role of cysteine in luciferin biosynthesis (Oba et al., 2013b) and recycling (Okada et al., 1974). We also detected a combined adenylyl-sulfate kinase and sulfate adenylyltransferase enzyme (ASKSA) among the lantern-enriched gene list (Appendix 4—figure 8), implicating active biosynthesis of 3'-phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphosulfate (PAPS), the cofactor of LST, in the lantern. This finding highlights the importance of LST-catalyzed luciferin sulfonation for bioluminescence. These firefly orthologs of ASKSA are the only members amongst their paralogs to contain a PTS1 (Appendix 4—figure 8), suggesting specialized localization to the peroxisome, the location of the luminescence reaction. This suggests that the levels of sulfoluciferin and luciferin may be actively regulated within the peroxisome of lantern cells in response to luminescence. Overall, our findings of several directly orthologous enzymes that share expression patterns in the light organs of both P. pyralis and A. lateralis suggests that the enzymatic physiology and/or the gene expression patterns of the photocytes were already fixed in the Luciolinae-Lampyrinae ancestor.

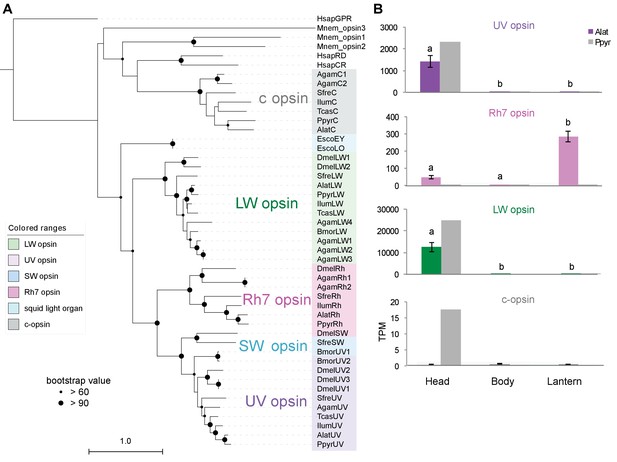

We also performed a similar expression analysis for genes not annotated as enzymes, yielding several genes with predicted lysosomal function (Appendix 4—table 6; Appendix 4.4). This suggests that the abundant but as yet unidentified ‘differentiated zone granule’ organelles of the firefly light organ (Ghiradella and Schmidt, 2004) could be lysosomes. Interestingly, we found a HE (TPM value ~300) and DE opsin, Rh7, in the light organ of A. lateralis, but not P. pyralis (Appendix 4—figure 9; Appendix 4.5), suggesting a potential light perception role for Rh7 in the A. lateralis lantern, akin to the light perception role described for Drosophila Rh7 (Ni et al., 2017).

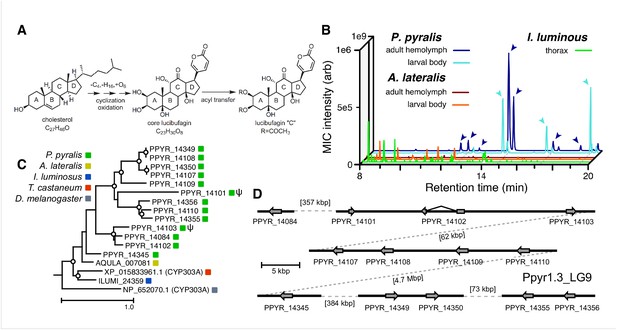

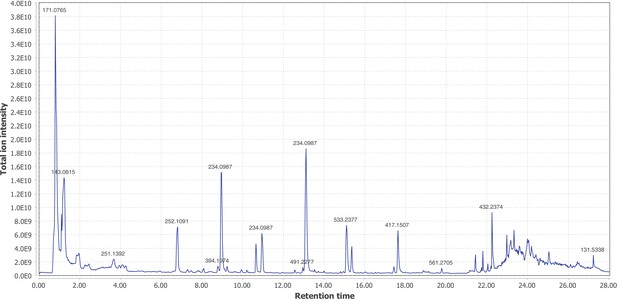

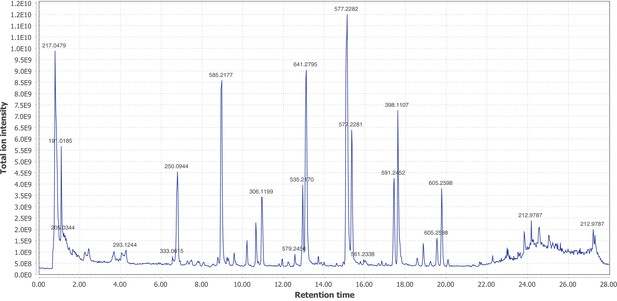

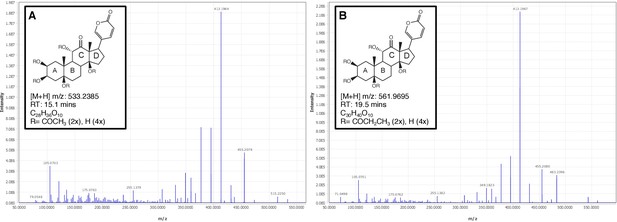

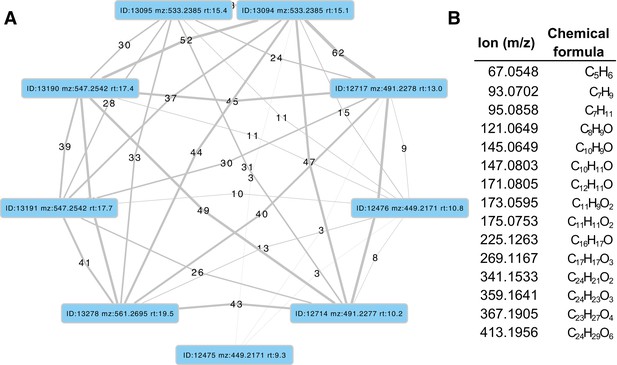

Genomic insights into firefly chemical defense

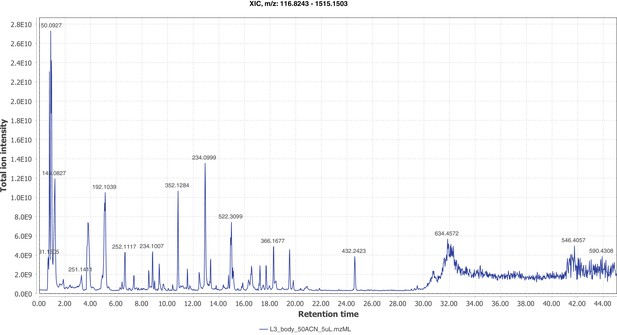

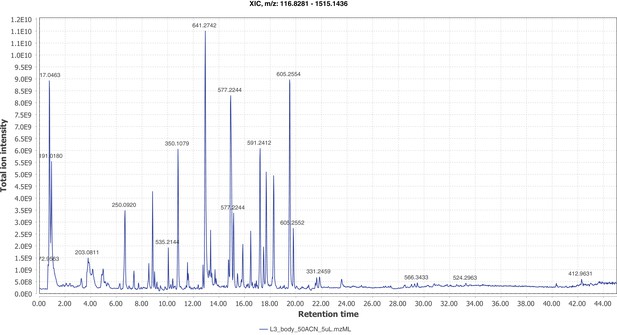

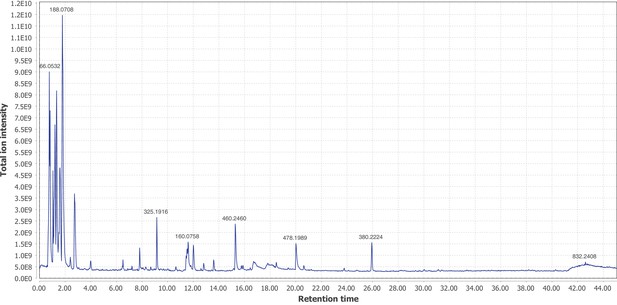

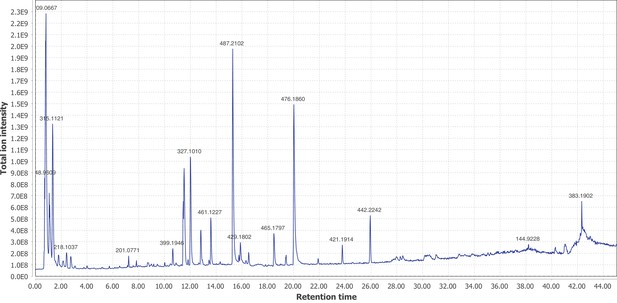

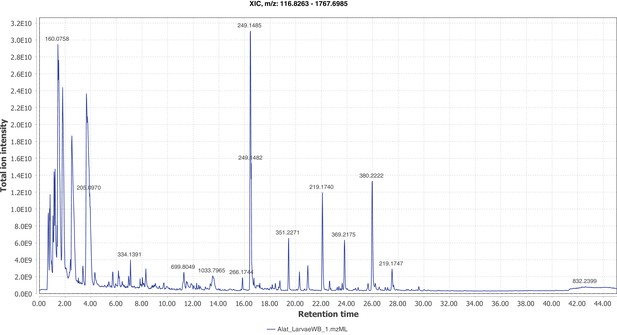

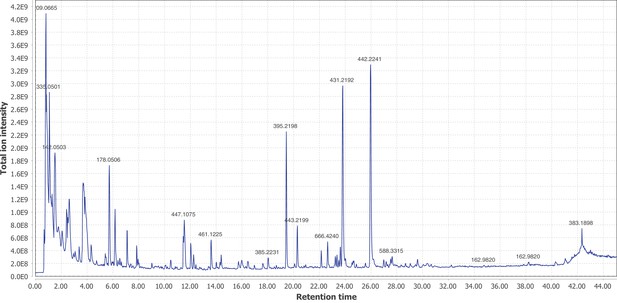

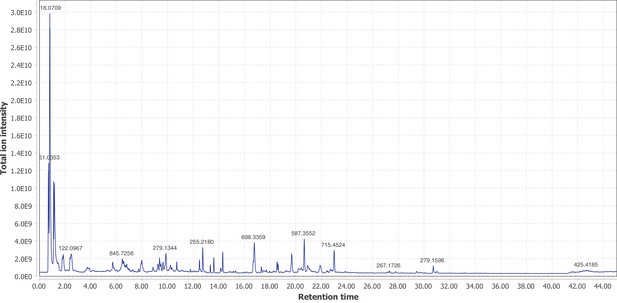

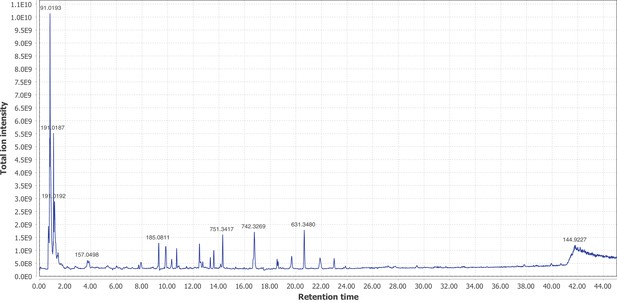

Firefly bioluminescence is postulated to have first evolved as an aposematic warning of larval chemical defenses (Branham and Wenzel, 2003). Lucibufagins are abundant unpalatable defense steroids described from certain North American firefly species, most notably in the genera Photinus (Meinwald et al., 1979), Lucidota (Gronquist et al., 2005), and Ellychnia (Smedley et al., 2017), and hence are candidates for ancestral firefly defense compounds. To test whether lucibufagins are widespread among bioluminescent beetles, we assessed the presence of lucibufagins in P. pyralis, A. lateralis, and I. luminosus by liquid-chromatography high-resolution accurate-mass mass-spectrometry (LC-HRAM-MS). While lucibufagins were found in high abundance in P. pyralis adult hemolymph, they were not observed in A. lateralis adult hemolymph, nor in I. luminosus metathorax extract (Figure 6B; Appendix 4.6). Since chemical defense is presumably most critical in the long-lived larval stage, we next tested whether lucibufagins are present in all firefly larvae even if they are not present in the adults of certain species. We found lucibufagins in P. pyralis larval extracts; however, they were not observed in A. lateralis larval extracts (Figure 6B; Appendix 4.6). Together, these results suggest that the lucibufagin biosynthetic pathway is either a derived trait only found in particular firefly taxa (e.g. subfamily: Lampyrinae), or that lucibufagin biosynthesis was an ancestral trait that was lost in A. lateralis. Consistent with the former hypothesis, the presence of lucibufagins in non-North-American Lampyrinae has been previously reported (Tyler et al., 2008), but to date there are no reports of lucibufagins in the Luciolinae.

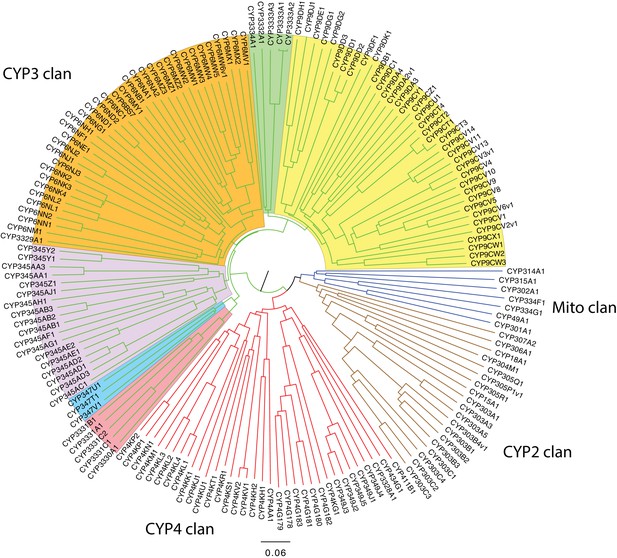

An expansion in the CYP303-P450 family correlates with lucibufagin content.

(A) Hypothesized lucibufagin biosynthetic pathway, starting from cholesterol. (B) LC-HRAM-MS multi-ion-chromatograms (MIC) showing the summation of exact mass traces for the [M + H]+ of 11 lucibufagin chemical formulas ± 5 ppm, calibrated for run-specific systematic m/z error (Appendix 4—table 9). Y-axis upper limit for P. pyralis adult hemolymph and larval body extract is 1000x larger than other traces. Arrows (blue/teal) indicate features with high MS2 spectral similarity to known lucibufagins. Sporadic peaks in A. lateralis body, and I. luminosus thorax traces are not abundant, preventing MS2 spectral acquisition and comparison, but do not match the m/z and RT of P. pyralis lucibufagins (Appendix 4.6). (C) Maximum likelihood tree of CYP303 family cytochrome P450 enzymes from P. pyralis, A. lateralis, T. castaneum, and D. melanogaster. P. pyralis shows a unique CYP303 family expansion, whereas the other species only have a single CYP303. Circles represent node bootstrap support >60%. Branch length measures substitutions per site. Pseudogenes are annotated with the greek letter Ψ (Appendix 1.10.1; 4.2.4). (D) Genomic loci for P. pyralis CYP303 family genes. These genes are found in multiple gene clusters on LG9, supporting origin via tandem duplication. Introns >4 kbp are shown.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

CYP303 multiple sequence alignment and gene tree for Figure 6C.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.017

The lucibufagin biosynthetic pathway is currently unknown. However, their chemical structure suggests a biosynthetic origin from cholesterol followed by a series of hydroxylations, -OH acetylations, and the side-chain oxidative pyrone formation (Figure 6A) (Meinwald et al., 1979). We hypothesized that cytochrome P450s, an enzyme family widely involved in metabolic diversification of organic substrates (Hamberger and Bak, 2013), could underlie several oxidative reactions in the proposed lucibufagin biosynthetic pathway. We therefore inferred the P450 phylogeny among our three bioluminescent beetle genomes to identify any lineage-specific genes correlated with lucibufagin presence. Our analysis revealed a unique expansion of one P450 family, the CYP303 family, in P. pyralis. While 94/97 of currently sequenced winged-insect genomes on OrthoDB (Zdobnov et al., 2017), as well as the A. lateralis and I. luminosus genomes, contain only a single CYP303 family gene, the P. pyralis genome contains 11 CYP303 genes and two pseudogenes (Figure 6C), which expanded via tandem duplication on the same linkage group (Figure 6D). The CYP303 ortholog of D. melanogaster, CYP303A1, has been shown to play a role in mechanosensory bristle development (Willingham and Keil, 2004). Although the exact biochemical function and substrate of D. melanogaster CYP303A1 is unknown, its closely related P450 families operate on an insect steroid hormone ecdysone (Willingham and Keil, 2004). As ecdysone and lucibufagins are structurally similar, CYP303 may operate on steroid-like compounds. Therefore, the lineage-specific expansion of the CYP303 family in P. pyralis is a compelling candidate in the metabolic evolution of lucibufagins as chemical defenses associated with the aposematic role of bioluminescence. Alternatively, this CYP303 expansion in P. pyralis may be associated with other lineage-specific chemical traits, such as pheromone production.

Symbionts of bioluminescent beetles

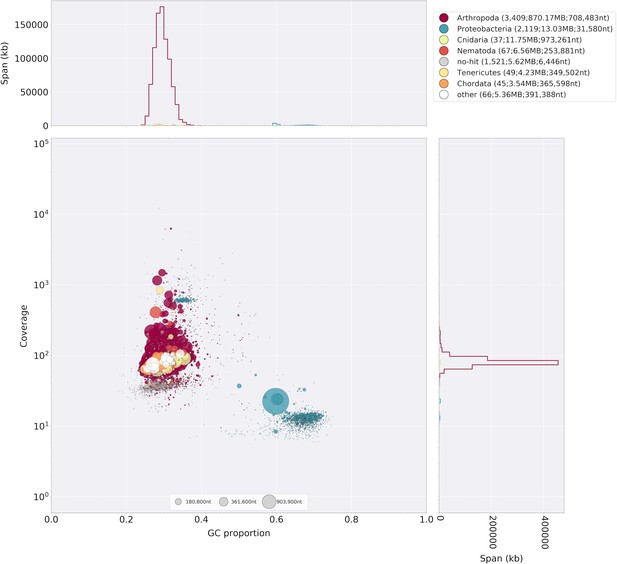

Given the increasingly recognized contributions of symbionts to host metabolism (Newman and Cragg, 2015), we characterized the hologenome of all three beetles as potential contributors to metabolic processes related to bioluminescence. Whole genome sequencing of our wild-caught and laboratory reared fireflies revealed a rich microbiome. Amongst our firefly genomes, we found various bacterial genomes, viral genomes, and the complete mtDNA for a phorid parasitoid fly, Apocephalus antennatus, the first mtDNA reported for genus Apocephalus. This mtDNA was inadvertently included in the P. pyralis PacBio library via undetected parasitization of the initial specimens, and was assembled via a metagenomic approach (Appendix 5.2). Independent collection of A. antennatus which emerged from field-collected P. pyralis adults and targeted COI sequencing later confirmed the taxonomic origin of this mtDNA (Appendix 5.3). We also sequenced and metagenomically assembled the complete circular genome (1.29 Mbp, GC: 29.7%; ~50x coverage) for a P. pyralis-associated mollicute (Phylum: Tenericutes), Entomoplasma luminosum subsp. pyralis (Appendix 5.1). Entomoplasma spp. were first isolated from the guts of North American fireflies (Hackett et al., 1992) and our assembly provides the first complete genomic assembly of any Entomoplasma species. Broad read coverage for the E. luminosus subsp. pyralis genome was detected in 5/6 of our P. pyralis DNA libraries, suggesting that Entomplasma is a highly prevalent, possibly vertically inherited, P. pyralis symbiont. It has been hypothesized that these Entomoplasma mollicutes could play a role in firefly metabolism, specifically via contributing to cholesterol metabolism and lucibufagin biosynthesis (Smedley et al., 2017).

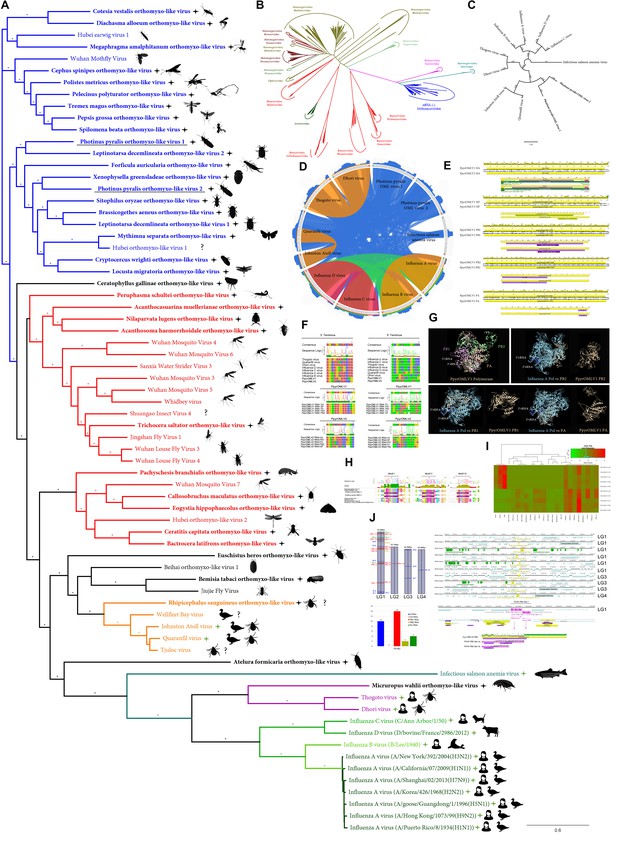

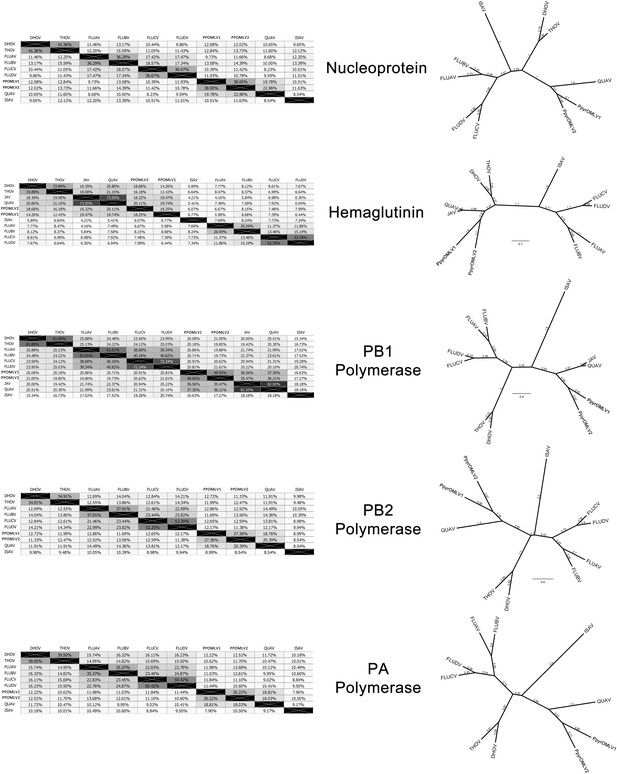

Within our unfiltered A. lateralis genomic assembly (Alat1.2), we also found 43 scaffolds (2.3 Mbp; GC:29.8%, ~64x coverage), whose taxonomic annotation corresponded to the Tenericutes (Appendix 2.5.2), suggesting that A. lateralis may also harbor a mollicute symbiont. Alat1.2 also contains 2119 scaffolds (13.0 Mbp, GC:63.7%, ~25x coverage) annotated as of Proteobacterial origin. Limited Proteobacterial symbionts were detected in the I. luminosus assembly (0.4 Mbp; GC:30–65% ~10x coverage) (Appendix 3.5.2), suggesting no stable symbiont is present in adult I. luminosus. Lastly, we detected two species of novel orthomyxoviridae-like ssRNA viruses, which we dub Photinus pyralis orthomyxo-like virus 1 and 2 (PpyrOMLV1/2), that were highly prevalent across our P. pyralis RNA-Seq datasets, and showed multi-generational transovarial transmission in the laboratory (Appendix 5.4). We also found several endogenous viral elements (EVEs) for PpyrOMLV1/2 in P. pyralis (Appendix 5.5). These viruses are the first reported in any firefly species, and represent only the second report of transgenerational transfer of any Orthomyxoviridae virus (Marshall et al., 2014), and the second report of Orthomyxoviridae derived EVEs (Katzourakis and Gifford, 2010). Together, these genomes from the firefly holobiont provide valuable resources for the continued inquiry of the symbiotic associates of fireflies and their biological and ecological significance.

Discussion

Here, we generated genome assembles, diverse tissue and life-stage RNA-Seq data, and LC/MS data for three evolutionarily informative and historically well-studied bioluminescent beetles, and used a series of comparative analyses to illuminate long-standing questions on the origins and evolution of beetle bioluminescence. By analyzing the genomic synteny and molecular evolution of the beetle luciferases and their extant and inferred-ancestral homologs, we found strong support for the independent origins of luciferase, and therefore bioluminescence, between fireflies and click beetles. Our approaches and analyses lend molecular evidence to the previous morphology-phylogeny based hypotheses of parallel gain proposed by Darwin and others (Darwin, 1872; Branham and Wenzel, 2003; Costa, 1975; Sagegami-Oba et al., 2007; Bocakova et al., 2007; Oba, 2009; Day, 2013). While our elaterid luciferase selection analysis strongly supports an independent gain, we did not perform an analogous selection analysis of luciferase homologs across all bioluminescent beetles, due to the lack of genomic data from key related beetle families. Additional genomic information from early-diverged firefly lineages, other luminous beetle taxa (e.g. Phengodidae and Rhagophthalmidae), and non-luminous elateroid taxa (e.g. Cantharidae and Lycidae), will be useful to further develop and test models of luciferase evolution, including the hypothesis that bioluminescence also originated independently in the Phengodidae and/or Rhagophthalmidae. As some phylogenetic relationships of fireflies and other lineages of superfamily Elateroidea remain uncertain, continued efforts to produce reference phylogeny for these taxa are required (Martin et al., 2017; Bocak et al., 2018). Toward this goal, the recently published Pyrocoelia pectoralis Lampyrinae firefly genome is an important advance which will contribute to future phylogenetic and evolutionary studies (Fu et al., 2017).

The independent origins of the firefly and click beetle luciferases provide an exemplary natural model system to understand enzyme evolution through parallel mutational trajectories and the evolution of complex metabolic traits generally. The abundance of gene duplication events of PACSs and ACSs at the ancestral luciferase locus in both fireflies and I. luminosus suggests that ancestral promiscuous enzymatic activities served as raw materials for the selection of new adaptive catalytic functions (Weng, 2014). But while parallel evolution of luciferase implies evolutionary independence of bioluminescence overall, the reality may be more complex, and the other subtraits of bioluminescence amongst the bioluminescent beetles likely possess different evolutionary histories from luciferase. While subtraits presumably dependent on an efficient luciferase, such as specialized tissues and neural control, almost certainly arose well after luciferase specialization, and thus can be inferred to also have independent origins between fireflies and click beetles, luciferin, which was presumably a prerequisite to luciferase neofunctionalization, may have been present in their common ancestor. Microbial endosymbionts, such as the tenericutes detected in our P. pyralis and A. lateralis datasets, are intriguing candidate contributors to luciferin metabolism and biosynthesis. Alternatively, recent reports have shown that firefly luciferin is readily produced non-enzymatically by mixing benzoquinone and cysteine (Kanie et al., 2016), and that a compound resulting from the spontaneous coupling of benzoquinone and cysteine acts as a luciferin biosynthetic intermediate in A. lateralis (Kanie et al., 2018). Benzoquinone is known to be a defense compound of distantly related beetles (Dettner, 1987) and other arthropods (e.g. millipedes) (Shear, 2015). Therefore, the evolutionary role of sporadic low-level luciferin synthesis through spontaneous chemical reactions, either in the ancestral bioluminescent taxa themselves, or in non-bioluminescent taxa, and dietary acquisition of luciferin by either the ancestral or modern bioluminescent taxa, should be considered. To decipher between these alternative evolutionary possibilities, the discovery of genes involved in luciferin metabolism in fireflies and other bioluminescent beetles will be essential. Here, as a first step toward that goal, we identified conserved, enriched and highly expressed enzymes of the firefly lantern that are strong candidates in luciferin metabolism and the elusive luciferin de novo biosynthetic pathway. Ultimately focused experimentation will be needed to decipher the biochemical function of these enzymes.

The early evolution of firefly bioluminescence was likely associated with an aposematic role. The adaptive light production of the primordial firefly (or alternatively, a primordial bioluminescent cantharoid beetle) that enabled the selection and neofunctionalization of luciferase was perhaps linked to a response to predators by a primitive whole-body oxygen-gated luminescence, where a startle-response mediated increase in hemolymph oxygenation through spiracle opening and escape locomotion caused a concomitant increase in luminescence (Buck and Case, 2002; Case, 2004). Alternatively, an early role for firefly luminescence in mate attraction has not been ruled out (Buck and Case, 2002). The presence of particular unpalatable defense compounds in all extant fireflies would be consistent with an ancestral role and the former hypothesis, and the chemical analysis of tissues across species and life stages presented in this work provides new insights into the evolutionary occurrence of lucibufagins, the most well-studied defense compounds associated with fireflies. Our results reject lucibufagins as ancestral defense compounds of fireflies, but rather suggest them as a derived metabolic trait associated with Lampyrinae. Additional chemical analyses across more lineages of fireflies are needed, however, to further support or falsify this hypothesis. Toward this goal, the high sensitivity of our LC-HRAM-MS and MS2 molecular networking-based lucibufagin identification approach is particularly well suited to broadened sampling in the future, including those of rare taxa and possibly museum specimens. Combined with genomic data showing a concomitant expansion of the CYP303 gene family in P. pyralis, we present a promising path toward elucidating the biosynthetic mechanism underlying these potent firefly toxins.

Overall, the resources and analyses generated in this study shed valuable light on the evolutionary questions Darwin first pondered, and will enable future studies of the ecology, behavior, and evolution of bioluminescent beetles. These resources will also accelerate the discovery of new enzymes from bioluminescent beetles that could enhance biotechnological applications of bioluminescence. Finally, we hope that the genomic resources shared here will facilitate the development of effective population genomic tools to monitor and protect wild bioluminescent beetle populations in the face of changing climate and habitats.

Materials and methods

Detailed materials and methods are available in the Appendices. Methods relating to P. pyralis are given in Appendix 1, while methods relating to A. lateralis and I. luminosus are given in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3, respectively. Methods for comparative genomic analyses are given in Appendix 4, while methods for microbiome characterization are given in Appendix 5. References to relevant sections of the Appendices are placed in-line throughout the maintext.

Data and materials availability

Request a detailed protocolGenomic assemblies (Ppyr1.3, Alat1.3, and Ilumi1.2), associated official geneset data, a SequenceServer (Priyam et al., 2015) BLAST server, and a JBrowse (Skinner et al., 2009) genome browser are available at www.fireflybase.org. Raw genomic and RNA-Seq reads for P. pyralis, A. lateralis, and I. luminosus, are available under the NCBI/EBI/DDBJ BioProjects PRJNA378805, PRJDB6460, and PRJNA418169 respectively. Raw WGBS reads can be found on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE107177). Mitochondrial genomes for P. pyralis and I. luminosus and A. antennatus are available on NCBI GenBank with accessions KY778696, MG242621, and MG546669. The complete genome of Entomoplasma luminosum subsp. pyralis is available on NCBI GenBank with accession CP027019. The viral genomes for Photinus pyralis orthomyxo-like virus 1 and 2 are available on NCBI Genbank with accessions MG972985-MG972994. LC-MS data is available on MetaboLights (Accession MTBLS698). Other supporting datasets are available on FigShare (Appendix 6.1).

Appendix 1

Photinus pyralis additional information

1.1 Taxonomy, biology, and life history

Photinus pyralis (Linnaeus, 1767) is amongst the most widespread and abundant of all U.S. fireflies (Lloyd, 1966; Lloyd, 2008). It inspired extensive work on the biochemistry and physiology of firefly bioluminescence in the early 20th century, and the first luciferase gene was cloned from this species (de Wet et al., 1985). A habitat generalist, P. pyralis occurs in fields, meadows, suburban lawns, forests, and woodland edges, and even urban environments. For example, the authors have observed P. pyralis flashing in urban New York City and Washington D.C. Adults rest on vegetation during the day and signaling begins as early as 20 min before sunset (Lloyd, 1966). Male flashing is cued by ambient light levels, thus shaded or unshaded habitats can show up to a 30 min difference in the initiation of male flashing (Lloyd, 1966). Males can be cued to flash outside of true twilight if exposed to light intensities simulating twilight (Case, 2004). P. pyralis were also reported to flash during totality of the total solar eclipse of 2017 (Personal communication: L.F. Faust, M.A. Branham). Courtship activity lasts for 30–45 min and both sexes participate in a bioluminescent flash dialog, as is typical for Photinus fireflies.

Males initiate courtship by flying low above the ground while repeating a single ~300 ms patrol flash at ~5–10 s intervals (Case, 2004). Males emit their patrol flash while dipping down and then ascending vertically, creating a distinctive J-shaped flash gesture (Lloyd, 1966; Case, 2004) (Figure 1A). During courtship, females perch on vegetation and respond to a male patrol flash by twisting their abdomen toward the source of the flash and giving a single response flash given after a 2–3 s delay (Video 1). Receptive females will readily respond to simulated male flashes, such as those produced by an investigator’s penlight. Females have fully developed wings and are capable of flight. Both sexes are capable of mating several times during their adult lives. During mating, males transfer to females a fitness-enhancing nuptial gift consisting of a spermatophore manufactured by multiple accessory glands (van der Reijden et al., 1997); the molecular composition of this nuptial gift has recently been elucidated for P. pyralis (Al-Wathiqui et al., 2016). In other Photinus species, male gift size decreases across sequential matings (Cratsley et al., 2003), and multiple matings are associated with increased female fecundity (Rooney and Lewis, 2002).

Adult P. pyralis live 2–3 weeks, and although these adults are typically considered non-feeding, both sexes have been reported drinking nectar from the flowers of the milkweed Asclepias syriaca (Faust and Faust, 2014). Mated females store sperm and lay ~30–50 eggs over the course of a few days on moss or in moist soil. The eggs take 2–3 weeks to hatch. Larval bioluminescence is thought to be universal for the Lampyridae, where it appears to function as an aposematic warning signal. Like other Photinus, P. pyralis larvae are predatory, live on and beneath the soil, and appear to be earthworm specialists (Hess, 1920). In the northern parts of its range, slower development likely requires P. pyralis to overwinter at least twice, most likely as larvae. Farther south, P. pyralis may complete development within several months, achieving two generations per year (Faust, 2017), which may be possibly be observed in the South as a ‘second wave’ of signalling P. pyralis in September-October.

Anti-predator chemical defenses of male P. pyralis include several bufadienolides, known as lucibufagins, that circulate in the hemolymph (Meinwald et al., 1979). Pterins have also been reported to be abundant in P. pyralis (Goetz et al., 1981); however, the potential defense role of these compounds has never been tested (Personal communication: J. Meinwald). When attacked, P. pyralis males release copious amounts of rapidly coagulating hemolymph and such ‘reflex-bleeding’ may also provide physical protection against small predators (Blum and Sannasi, 1974; Faust et al., 2012).

1.2 Species distribution

Although Photinus pyralis is widely distributed in the Eastern United States, published descriptions of its range are limited, with the notable exception of Lloyd’s 1966 monograph (Lloyd, 1966) which addresses the range of many Photinus species. We therefore sought to characterize the current distribution of P. pyralis in order to produce an updated map to inform our experimental design and enable future population genetic studies. Four sources of data were used to produce the presented range map of P. pyralis: (i) Field surveys by the authors (ii) Published (Lloyd, 1966; Luk et al., 2011) and unpublished sightings of P. pyralis at county level resolution, provided by Dr. J. Lloyd (University of Florida), (iii) coordinates and dates of P. pyralis sightings, obtained by targeted e-mail surveys to firefly field biologists, (iv) citizen scientist reports of P. pyralis through the iNaturalist platform (iNaturalist, 2017). iNaturalist sightings were manually curated to only include reports which could be unambiguously identified as P. pyralis from the photos, and also that also included GPS geotagging to <100 m accuracy. A spreadsheet of these sightings is available on FigShare (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.5688826).

QGIS (v2.18.9, OSG Foundation, 2017) was used for data viewing and figure creation. A custom Python script (Fallon, 2018e; copy archived at https://github.com/elifesciences-publications/2017_misc_scripts) within QGIS was used to link P. pyralis sightings to counties from the US census shapefile (United States Census Bureau, 2017). Outlying points that were located in Desert Ecoregions of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Terrestrial Ecoregions shapefile (Olson et al., 2001; World Wildlife Fund, 2017) or the westernmost edge of the range were manually removed, as they are likely isolated populations not representative of the contiguous range. For Figure 1B, these points were converted to a polygonal range map using the ‘Concave hull’ QGIS plugin (‘nearest neighbors = 19’) followed by smoothing with the Generalizer QGIS plugin with Chaiken’s algorithm (Level = 10, and Weight = 3.00). Below (Appendix 1—figure 1), red circles indicate county-centroided presence records.

Detailed geographic distribution map for P. pyralis.

P. pyralis sightings (red circles show county centroided reports) in the United States and Ontario, Canada (diagonal hashes). The World Wildlife Fund Terrestrial Ecoregions (Olson et al., 2001; World Wildlife Fund, 2017) are also shown (colored shapes). The P. pyralis sighting dataset shown is identical to that used to prepare Figure 1B.

In our field surveys, we found that the range of P. pyralis was notably extended from the range reported by Lloyd, specifically we found P. pyralis in abundance to the west of the Mill river in Connecticut. P. pyralis is found with confidence roughly from Connecticut to Texas, and possibly as far south as Guatemala (Personal communication: A. Catalán). These possible southern populations require further study.

1.3 Specimen collection and identification

Adult male P. pyralis specimens for Illumina short-insert and mate-pair sequencing were collected at sunset on June 13th, 2011 near the Visitor’s Center at Great Smoky Mountains National Park (permit to Dr. Kathrin Stanger-Hall). Specimens were identified to species and sex via morphology (Green, 1956), flash pattern and behavior (Lloyd, 1966), and cytochrome-oxidase I (COI) similarity (partial sequence: primers HCO, LCO [Stanger-Hall and Lloyd, 2015]) when blasted against an in-house database of firefly COI nucleotide sequences. Collected fireflies were stored in 95% ethanol at −80˚C until DNA extraction.

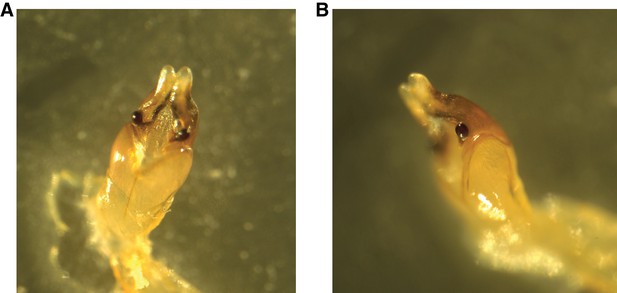

Adult male P. pyralis specimens for Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RSII sequencing were captured during flight at sunset on June 9th, 2016, from Mercer Meadows in Lawrenceville, NJ (40.3065 N 74.74831 W), on the basis of the characteristic ‘rising J’ flash pattern of P. pyralis (permit to TRF via Mercer County Parks Commission). Collected fireflies were sorted, briefly checked to be likely P. pyralis by the presence of the margin of ventral unpigmented abdominal tissue anterior to the lanterns, flash frozen with liquid N2, lyophilized, and stored at −80˚C until DNA extraction. A single aedeagus (male genitalia) was dissected from the stored specimens and confirmed to match the P. pyralis taxonomic key (Green, 1956) (Appendix 1—figure 2).

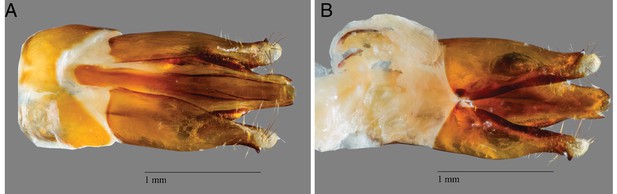

P. pyralis aedeagus (male genitalia).

(A) Ventral and (B) side view of a P. pyralis aedeagus dissected from specimens collected on the same date and locality as those used for PacBio sequencing. Note the strongly sclerotized paired ventro-basal processes (‘mickey mouse ears’) emerging from the median process, characteristic of P. pyralis (Green, 1956).

1.3.2 Collection and rearing of P. pyralis larvae

We intended to survey the lucibufagin content of P. pyralis larvae (Figure 6B; Appendix 4.6), and as well as the transovarial transmission of Photinus pyralis orthomyxo-like viruses from parent to larvae (Appendix 5.4), but as P. pyralis larvae are subterranean and extremely difficult to collect from the wild, we reared P. pyralis larvae from eggs laid from mated pairs. It is important to note that these P. pyralis larval rearing experiments were unexpectedly successful. Although there has been some success in laboratory rearing and domestication of Asian Aquatica spp. (Chiang and Yang, 2010), including the A. lateralis Ikeya-Y90 strain described in this manuscript, rearing of North American fireflies is considered extremely difficult with numerous unpublished failures for unclear reasons (Lloyd, 1996), and limited reports of successful rearing of mostly non-Photinus genera, including Photuris sp. (McLean et al., 1972), Pyractomena angulata (Buschman, 1988), and Pyractomena borealis (Personal communication: Scott Smedley). The below protocol for P. pyralis larval rearing is presented in the context of disclosure of the methods of this manuscript, and should be considered a preliminary, unoptimized rearing protocol. A full description of the P. pyralis larvae and it’s life history and behavior will be presented in a separate manuscript.

Four adult female P. pyralis were collected from the Bluemont Junction Trail in Arlington, VA from June 12th through June 18th 2017 (collection permission obtained by TRF from Arlington County Parks and Recreation department). The females were mated to P. pyralis males collected either from the same locality and date, or to males collected from Kansas in late June. Mating was performed by housing one to two males and one female in small plastic containers for ~1–3 days with a wet kimwipe to maintain humidity. Mating pairs were periodically checked for active mating, which in Photinus fireflies takes several hours. Successfully mated females were transferred to Magenta GA-7 plastic boxes (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and provided a ~4 cm x 4 cm piece of locally collected moss (species diverse and unknown) as egg deposition substrate, and allowed to deposit eggs until their death in ~1–4 days. Deceased females were removed, artificial freshwater (AFW; 1:1000 diluted 32 PSU artificial seawater) was sprayed into the box to maintain high humidity, and eggs were kept for 2–3 weeks at room temperature and periodically checked until hatching. Like other firefly eggs, the eggs of P. pyralis were observed to be faintly luminescent imaging using a cooled CCD camera (Appendix 1—figure 3); however, this luminescence was not visible to the dark-adapted eye, indicating that this luminescence is less intense than other firefly species such as Luciola cruciata (Harvey, 1952).

Upon hatching, first instar larvae were mainly fed ~1 cm cut pieces of Canadian Nightcrawler earthworms (Lumbricus terrestris; Windsor Wholesale Bait, Ontario, Canada), and occasional live White Worms (Enchytraeus albidus; Angels Plus, Olean, NY). Although P. pyralis first instar larvae were observed to attack live Enchytraeus albidus, an experiment to determine if this would be suitable as a single food source was not performed. Uneaten and putrefying earthworm pieces were removed after 1 day, and the container cleaned. Once the larvae had been manually fed for ~2 weeks and deemed sufficiently strong, they were transferred to plastic shoeboxes (P/N: S-15402, ULINE, USA) which were intended to mimic a soil ecosystem. In personal discussions of unpublished firefly rearing attempts by various firefly researchers, we noted that a common theme was the difficulty of preventing the uneaten prey of these predatory larvae from putrifying. Therefore, we sought to create ecologically inspired ‘eco-shoeboxes’, where fireflies would prey on live organisms, and other organisms would assist in cleanup of uneaten or partially eaten prey that had been fed to the firefly larvae, to prevent the growth of pathogenic microorganisms on uneaten prey.

First, these shoeboxes were filled with 1L of mixed 50% (v/v) potting soil, and 50% coarse sand (Quikrete, USA) that had been washed several times with distilled water to remove silt and dust. The soil-sand mix was wet well with AFW, and live Enchytraeus albidus (50+), temperate springtails (50+; Folsomia candida; Ready Reptile Feeders, USA), and dwarf isopods (50+; Trichorhina tomentosa; Ready Reptile Feeders, USA) were added to the box, and several types of moss, coconut husk, and decaying leaves were sparingly added to the corners of the box. The non-firefly organisms were included to mimic a primitive detritivore (Enchytraeus albidus and Trichorhina tomentosa) and fungivore (Folsomia candida) system. About 50 firefly larvae were included per box. No interactions between the P. pyralis larvae and the additional organisms were observed. Predation on Enchytraeus albidus seems likely, but careful observations were not made. Distilled water was sprayed into the box every ~2 days to maintain a high humidity. Throughout this period, live Lumbricus terrestris (~10–15 cm) were added to the box every 2–3 days as food. These earthworms were first prepared by washing with distilled water several times to remove attached soil, weakened and stimulated to secrete coelemic fluid and gut contents by spraying with 95% ethanol, washed several times in distilled water, and left overnight in ~2 cm depth distilled water at 4˚C. Anecdotally this pre-cleaning and preparation process reduced the rate and degree that dead earthworms putrefied. Young P. pyralis larvae were observed to successfully kill and gregariously feed on these live earthworms (Appendix 1—figure 4). The possibility that firefly larvae possess a paralytic venom used to stun or kill prey has been noted by other researchers (Hess, 1920; Williams, 1917). In our observations, an earthworm would immediately react to the bite from a single P. pyralis larvae, thrashing about for several minutes, but would then become seemingly paralyzed over time, supporting the role of a potent, possibly neurotoxic, firefly venom. The P. pyralis larvae would then begin extra-oral digestion and gregarious feeding on the liquified earthworm. Once the earthworm had been killed and broken apart by firefly larvae, Enchytraeus albidus would enter through gaps in the cuticle and begin to feed in large numbers throughout the interior of the earthworm. The other detritivores were observed at later stages of feeding. Between the combined action of the P. pyralis larvae, and the other detritivores, the live earthworm was completely consumed within 1–2 days, and no manual cleanup was required.

Compared to the initial manual feeding and cleaning protocol for P. pyralis 1st instar larvae, the ‘eco-shoebox’ rearing method was low-input and convenient for large numbers of larvae. The feeding and cleanup process was efficient for ~2 months (July through September), leading to a large number of healthy 3-4th instar larvae (Appendix 1—figure 5). However, after that point, P. pyralis larvae, possibly in preparation for a winter hibernation, seemingly became quiescent, and were less frequently seen patrolling throughout the box. At the same time, the Enchytraeus albidus earthworms were observed to become less abundant, either due to continual predation by P. pyralis, or due to population collapse from insufficient fulfillment of nutritional requirements from feeding of Enchytraeus albidus on Lumbricus terrestris alone.

At this point, earthworms were not consumed within 1–2 days, and became putrid, and P. pyralis which had been feeding on these earthworms were frequently found dead nearby, and themselves quickly putrefied. Generally after this point P. pyralis larvae were more frequently found dead and partially decayed, indicating the possibility of pathogenesis from microorganisms from putrefying earthworms. At this stage, it was observed that mites (Acari), probably from the soil contained in the guts of the fed earthworms, became abundant, and were observed to act as ectoparasitic on P. pyralis larvae. An attempt to simulate hibernation of P. pyralis larvae was made by storing them at 4˚C for ~3 weeks, however a large proportion (~30%) of larvae died during this hibernation to a seeming fungal infection. Other larvae revived quickly when returned to room temperature, but all Trichorhina tomentosa were killed by even transient exposure to 4˚C. To date, a smaller number of fifth and sixth instar P. larvae have been obtained, but pupation in the laboratory has not occured. The lack of pupation is unsurprising as it is likely occurs in the wild after 1–2 years of growth, is likely under temperature and photoperiodic control, and may require a licensing stage of cold temperature hibernation for several weeks. Overall, manual feeding of first1 st instar larvae followed by the ‘eco-shoebox’ method was unexpectedly successful approach for the maintenance and growth of P. pyralis larvae.

Luminescence of P. pyralis eggs.

(A) Photograph under ambient light of ~1 day post-deposition P. pyralis eggs. (B) Photograph of self-luminescence of ~1 day post-deposition P. pyralis eggs. Both photographs taken with a NightOwl LB98 cooled CCD luminescence imager (Berthold Technologies, USA). Luminescence was not visible to the dark-adapted eye.

Gregarious predation of young P. pyralis larvae on a live Lumbricus terrestris.

Both P. pyralis larvae (red arrows), and Enchytraeus albidus (yellow arrows), were observed to feed on the paralyzed earthworms.

Gregarious predation of 3rd-4th instar P. pyralis larvae on a live Lumbricus terrestris.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.36495.0241.4 Karyotype and genome size

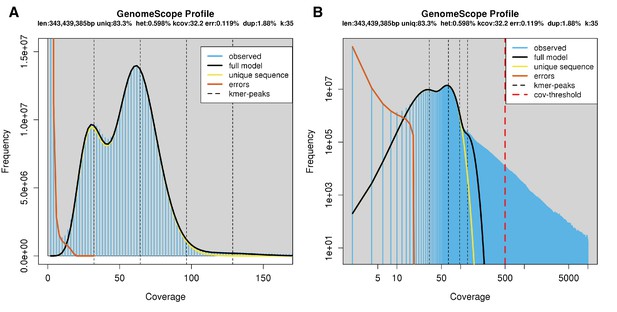

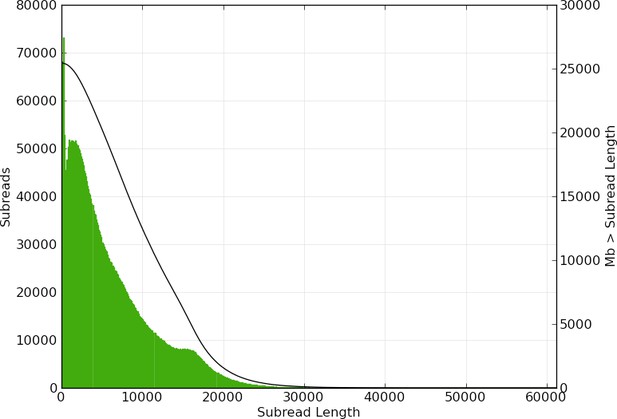

The karyotype of P. pyralis was previously reported to be 2n = 20 with XO sex determination (male, 18A + XO; female, 18A + XX) (Wasserman and Ehrman, 1986). The genome sizes of four P. pyralis adult males were previously determined to be 422 ± 9 Mbp (SEM, n = 4), whereas the genome sizes of five P. pyralis adult females were determined to be 448 ± 7 (SEM, n = 5) by nuclear flow cytometry analysis (Lower et al., 2017). From these analyses, the size of the X-chromosome is inferred to be ~26 Mbp. Genome size inference via kmer spectral analysis of the P. pyralis short-insert Illumina data from a single adult P. pyralis male estimated a genome size of 343 Mbp (Appendix 1—figure 6).

1.5 Library preparation and sequencing

See Appendix 4—table 1 for a overview of all sequence libraries. Library specific construction methods are detailed below.

1.5.1 Illumina

DNA was extracted from sterile-water-washed thorax of Great Smoky Mountains National Park collected specimens using phenol-chloroform extraction with RNAse digestion, checked for quality via gel electrophoresis, and quantified by Nanodrop or Qubit (Thermo Scientific, USA). To obtain sufficient DNA for both short insert and mate-pair library construction, libraries were constructed separately from DNA from each of two individual males and pooled DNA of three males, all from the same population. Males were selected for sequencing as they are more easily found in the field than females. In addition, as P. pyralis males are XO (Dias et al., 2007), differences in sequencing coverage could inform localization of scaffolds to the X chromosome. Illumina TruSeq short insert (average insert size: 300 bp) and Nextera mate-pair libraries (insert size: 3 Kbp, 6 Kbp) were constructed at the Georgia Genomics Facility (Athens, GA) and subsequently sequenced on two lanes of Illumina HiSeq2000 100 × 100 bp PE reads (University of Texas; Appendix 4—table 1).

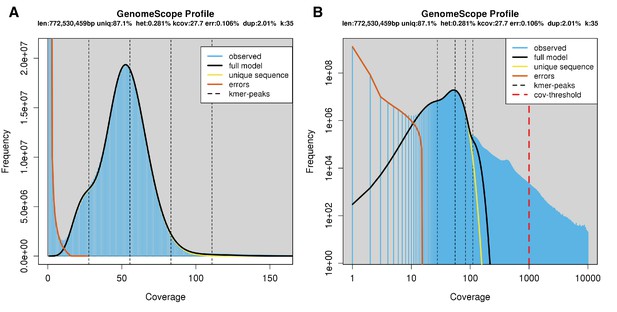

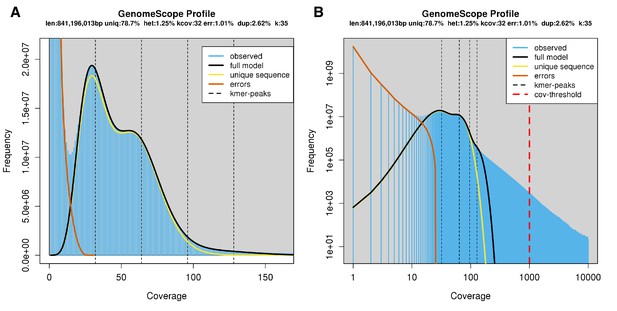

Genome scope kmer analysis of the P. pyralis short read library.

(A) Linear and (B) log plot of a kmer spectral genome composition analysis of the ‘8369’ P. pyralis Illumina short-read library from a single P. pyralis XO adult male (Appendix 1.5.1; Appendix 4—table 1) with jellyfish (v2.2.9; parameters: -C -k 35) (Marçais and Kingsford, 2011) and GenomeScope (v1.0; parameters: Kmer length = 35, Read length = 100, Max kmer coverage = 1000) (Vurture et al., 2017). len = inferred haploid genome length, uniq = percentage non-repetitive sequence, het = overall rate of genome heterozygosity, kcov = mean kmer coverage for heterozygous bases, err = error rate of the reads, dup: average rate of read duplications. These results are consistent with the genome size of a XO male, when possible systematic error of kmer spectral analysis and flow cytometry genome size estimates is considered. The heterozygosity is somewhat low when compared to some other arthropods.

1.5.2 PacBio

High-molecular-weight DNA (HMW DNA) was extracted from four pooled lyophilized adult male P. pyralis (dry mass 90.8 mg) from the MMNJ field site. These specimens were first externally washed using 95% ethanol, after which DNA extraction proceeded with a 100/G Genomic Tip plus Genomic Buffers kit (Qiagen, USA). DNA extraction followed the manufacturer's protocol, with the exception of the final precipitation step, where HMW DNA was pelleted with 40 µg RNA grade glycogen (Thermo Scientific, USA) and centrifugation (3000 x g, 30 min, 4 ˚C) instead of spooling on a glass rod. Although increased genomic heterozygosity from four pooled males and a resulting more complicated genome assembly was a concern for a wild population like P. pyralis, four males were used in order to extract enough DNA for workable coverage using 15 Kbp+ size selected PacBio RSII sequencing. All extracted DNA was used for library preparation, and all of the final library was used for sequencing. Adult males, being XO, were chosen over the preferable XX females, as adult males are much more easily captured because they signal during flight, whereas females are typically found in the brush below and generally only flash in response to authentic male signals.

Precipitated HMW DNA was redissolved in 80 µL Qiagen QLE buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.5) yielding 17.1 µg of DNA (214 ng/µL) and glycogen (500 ng/µL). Final DNA concentration was measured with a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) using the Qubit Broad Range kit. Manipulations hereafter, including HMW DNA size QC, fragmentation, size selection, library construction, and PacBio RSII sequencing, were performed by the Broad Technology Labs of the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA).

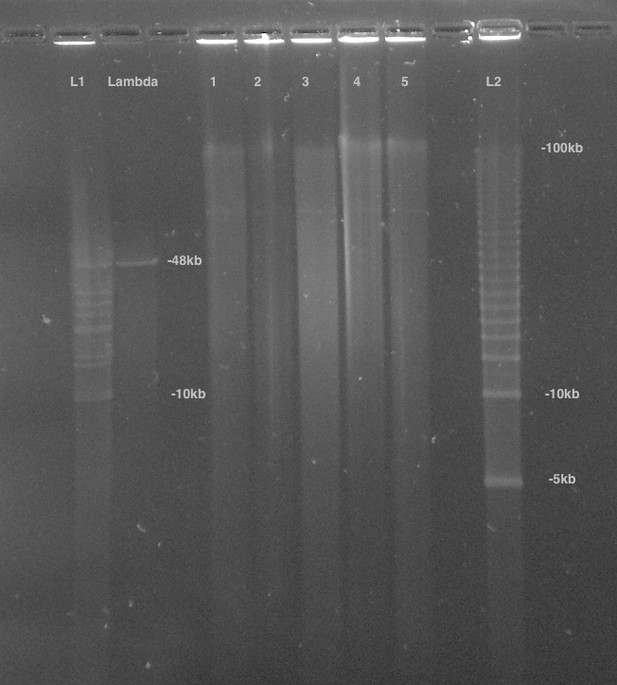

First, the size distribution of the HMW DNA was confirmed by pulsed-field-gel-electrophoresis (PFGE). In brief, 100 ng of HMW DNA was run on a 1% agarose gel (in 0.5x TBE) with the BioRad CHEF DRIII system. The sample was run out for 16 hr at six volts/cm with an angle of 120 degrees with a running temperature of 14 ˚C. The gel was stained with SYBRgreen dye (Thermo Scientific - Part No. S75683). 1 µg of 5 Kbp ladder (BioRad, part no 170–3624) was used as a standard. These results demonstrated the HMW DNA had a mean size of >48 Kbp (Appendix 1—figure 7). This pool of HMW DNA is designated 1611_PpyrPB1 (NCBI BioSample SAMN08132578).