A statistical framework to assess cross-frequency coupling while accounting for confounding analysis effects

Figures

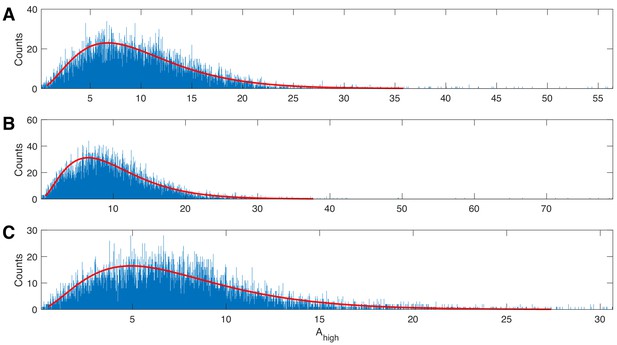

The gamma distribution provides a good fit to example human data.

Three examples of 20 s duration recorded from a single electrode during a human seizure. In each case, the gamma fit (red curve) provides an acceptable fit to the empirical distributions of the high frequency amplitude.

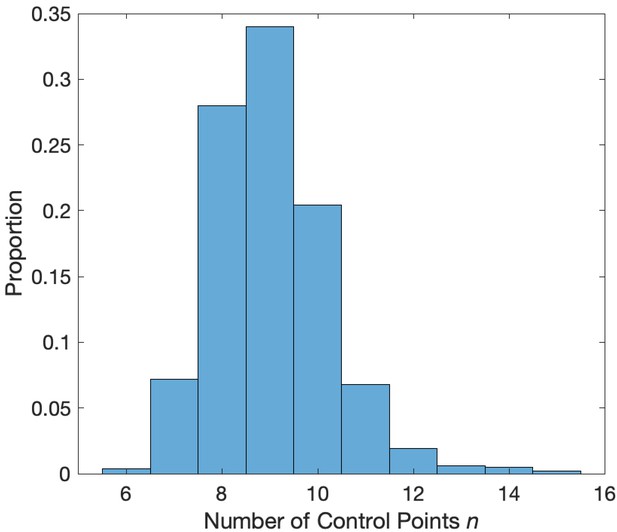

Distribution of the number of control points that minimize the AIC.

Values of between 7 and 12 minimize the AIC in a simulation with phase-amplitude coupling and amplitude-amplitude coupling.

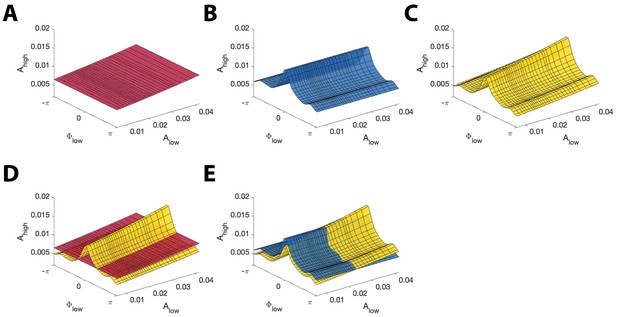

Example model surfaces used to determine and .

(A,B,C) Three example surfaces (A) , (B) , and (C) in the three-dimensional space (, , ). (D) The maximal distance between the surfaces (red) and (yellow) is used to compute . (E) The maximal distance between the surfaces (blue) and (yellow) is used to compute .

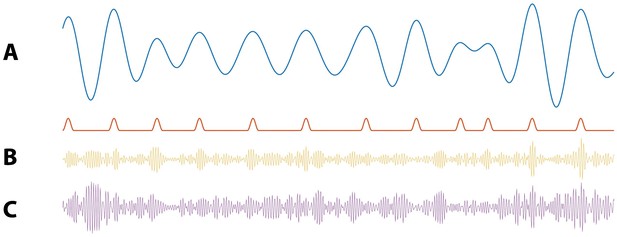

Illustration of synthetic time series with PAC and AAC.

(A) Example simulation of (blue) and modulation signal M (red). When the phase of is near 0 radians, M increases. (B) Example simulation of PAC. When the phase of is approximately 0 radians, the high frequency amplitude (yellow) increases. (C) Example simulations of AAC. When the amplitude of is large, so is the amplitude of the high frequency signal (purple).

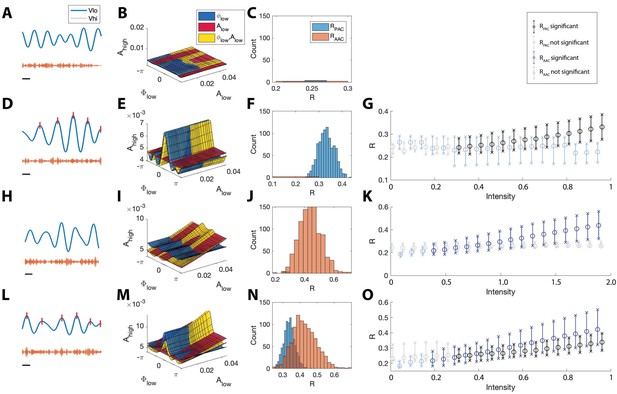

The statistical modeling framework successfully detects different types of cross-frequency coupling.

(A–C) Simulations with no CFC. (A) When no CFC occurs, the low frequency signal (blue) and high frequency signal (orange) evolve independently. (B) The surfaces , , and suggest no dependence of on or . (C) Significant (<0.05) values of and from 1000 simulations. Very few significant values for the statistics R are detected. (D–G) Simulations with PAC only. (D) When the phase of the low frequency signal is near 0 radians (red tick marks), the amplitude of the high frequency signal increases. (E) The surfaces , , and suggest dependence of on . (F) In 1000 simulations, significant values of frequently appear, while significant values of rarely appear. (G) As the intensity of PAC increases, so do the significant values of (black), while any significant values of remain small. (H–K) Simulations with AAC only. (H) The amplitudes of the high frequency signal and low frequency signal are positively correlated. (I) The surfaces , , and suggest dependence of on . (J) In 1000 simulations, significant values of frequently appear. (K) As the intensity of AAC increases, so do the significant values of (blue), while any significant values of remain small. (L–O) Simulations with PAC and AAC. (L) The amplitude of the high frequency signal increases when the phase of the low frequency signal is near 0 radians and the amplitude of the low frequency signal is large. (M) The surfaces , , and suggest dependence of on and . (N) In 1000 simulations, significant values of and frequently appear. (O) As the intensity of PAC and AAC increase, so do the significant values of and . In (G,K,O), circles indicate the median, and x’s the 5th and 95th quantiles.

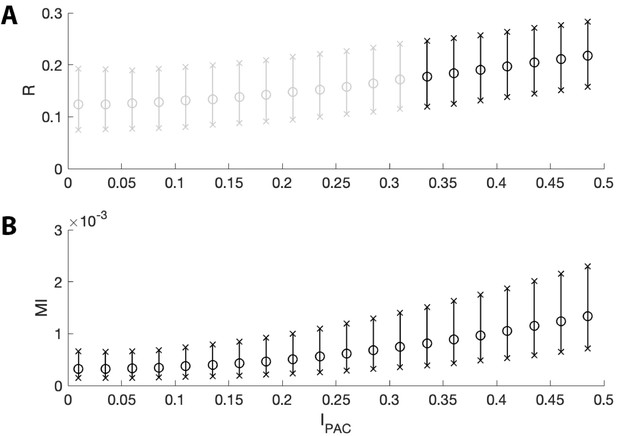

The two measures of PAC increase with intensities near zero.

The mean (circles) and 5th to 95th quantiles (x’s) of (A) and (B) MI for intensity values between 0 and 0.5. Black bars indicate or is below 0.05 for ≥95% of simulations; gray bars indicate is not below 0.05 for ≥95% of simulations. While both measures increase with intensity, MI detects more instances of significant PAC than does for very small values of .

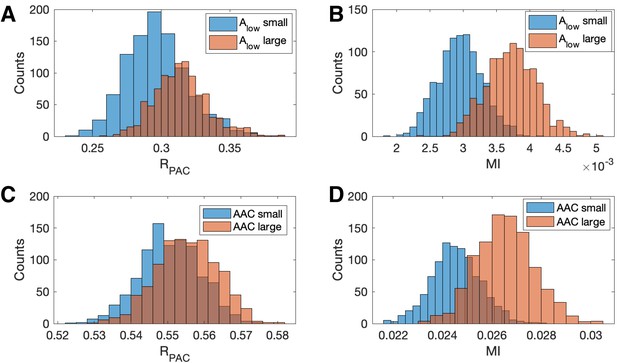

Increases in the amplitude of the low frequency signal, and the amplitude-amplitude coupling (AAC), increase the modulation index more than .

(A,B) Distributions of (A) and (B) MI when is small (blue) and when is large (red). (C,D) Distributions of (C) and (D) MI when AAC is small (blue) and when AAC is large (red).

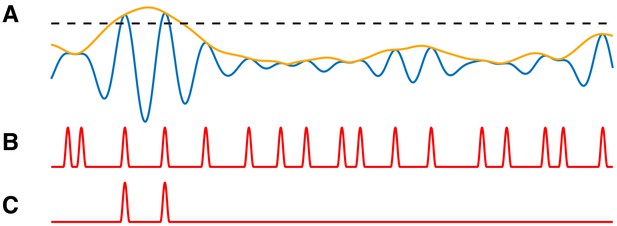

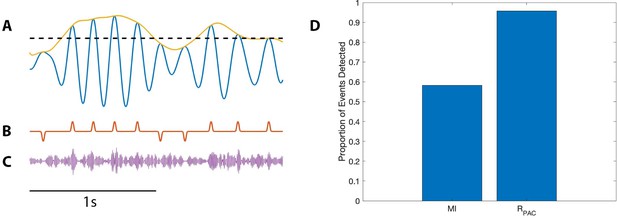

PAC events restricted to a subset of occurrences are still detectable.

(A) The low frequency signal (blue), amplitude envelope (yellow), and threshold (black dashed). (B–C) The modulation signal increases (B) at every occurrence of , or (C) only when exceeds the threshold and .

PAC with AAC is accurately detected with the proposed method, but not with the modulation index.

(A) The low frequency signal (blue), amplitude envelope (yellow), and threshold (black dashed). (B) The modulation signal (red) increases when and , and deceases when and . (C) The modulated signal (purple) increases and decreases with the modulation signal. (D) The proportion of significant detections (out of 1000) for MI and .

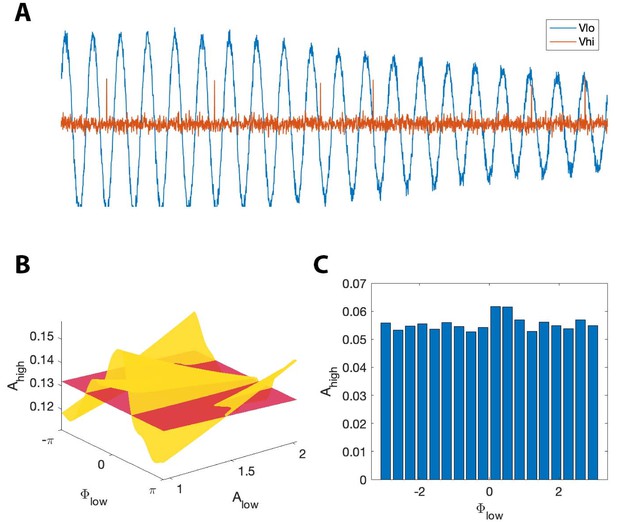

, but not MI, detects phase-amplitude coupling in a simple stochastic spiking neuron model.

(A) The phase and amplitude of the low frequency signal (blue) modulate the probability of a high frequency spike (orange). (B) The surfaces (red) and (yellow). The phase of maximal modulation depends on . (C) The modulation index fails to detect this type of PAC.

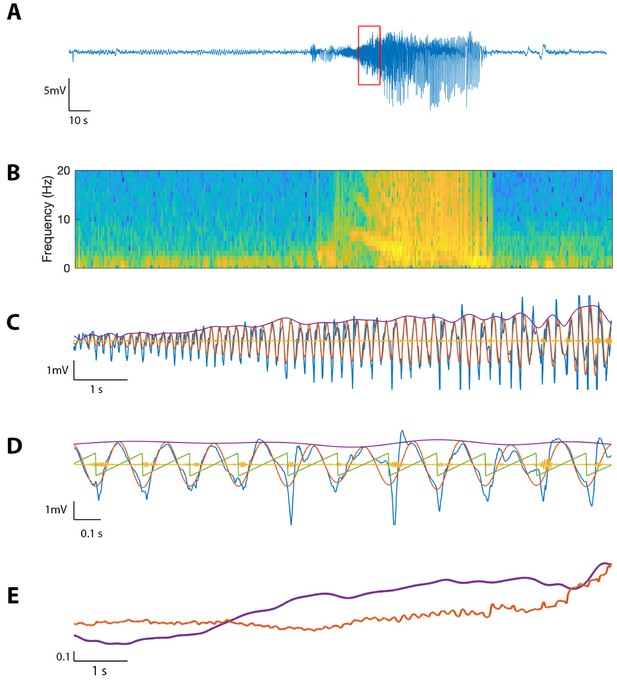

The proposed method detects cross-frequency coupling in an in vivo human recording.

(A,B) Voltage recording (A) and spectrogram (B) from one MEA electrode over the course of a seizure; PAC and AAC were computed for the time segment outlined in red. (C) The 10 s voltage trace (blue) corresponding to the outlined segment in (A), and (red), (yellow), and (purple). (D) A 2 s subinterval of the voltage trace (blue), (red), (yellow), (purple), and (green). (E) (purple) and (red) for the 10 s segment in (C), normalized and smoothed.

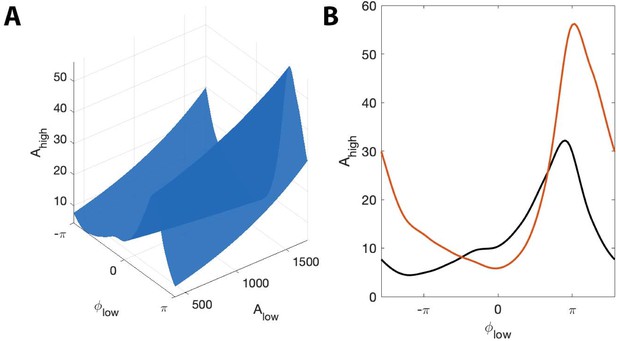

The surface shows how PAC changes with the low frequency amplitude and phase during an interval of human seizure.

(A) The full model surface (blue) in the (, , ) space, and components of that surface when (B) is small (black), and is large (red).

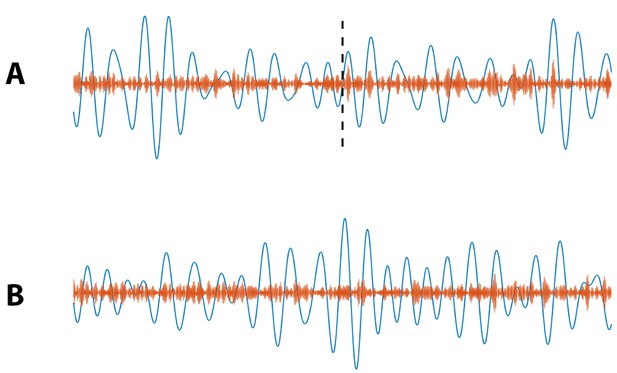

Example simulated (blue) and (orange) signals for which (A) PAC increases at 20 s (indicated by black dashed line), and (B) no increase in PAC occurs.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.44287.014Additional files

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.44287.015