The social life of Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus)

Figures

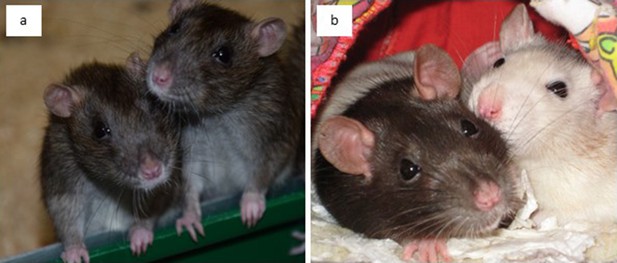

Wild and domesticated Norway rats.

Wild rats (panel [a] depicts two female wild-derived rats) differ from domesticated rats (panel [b] shows two female domesticated rats) greatly in respect to their coat colour but less so in their social life, which is illustrated by domesticated rats showing the full behavioural repertoire of wild rats. Therefore, domesticated rats can be good representatives of wild rats and vice versa.

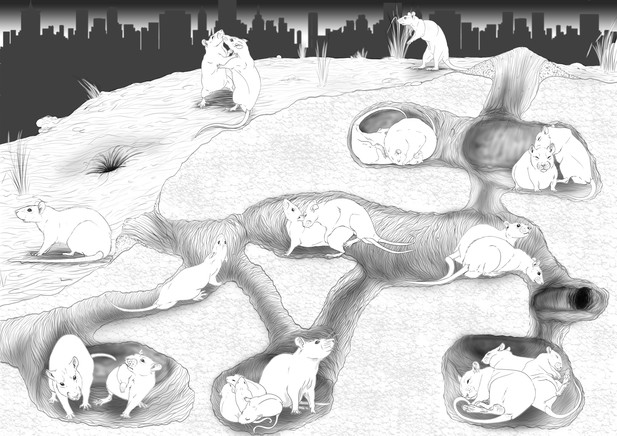

The social organisation of a rat colony.

Rats are social animals that live in large colonies, consisting of sometimes more than 150 female and male individuals with overlapping generations. Rats of a colony establish an underground burrow system with shared channels and chambers. In these chambers, they commonly huddle together to keep warm and often sleep like this (right chamber at the bottom and left at the top). Females establish their nest in such chambers, where they give birth to up to eight pups (middle chamber at the bottom). Colony members reproduce. Males approach females that respond defensively with sidekicks, if they are not in oestrus (left chamber at the bottom). If she is receptive, several males will copulate with her (two rats in the middle). Rats establish a dominance hierarchy, which is more pronounced in males than females. When rats meet, they inspect each other, whereby subordinate individuals show a submissive posture, crawl under the other or avoid such contacts to prevent conflict. Most conflicts, however occur between rats of different colonies. Fights typically start with a threat posture, followed by fights that are interrupted by standing upright and boxing (two rats outside the burrow system). Most commonly, however, rats show amicable behaviour with colony members. For example, they spend time in close proximity to each other (left side, middle rats) or groom each other (right chamber at the top). Drawings by Michelle Gygax.

Tables

Ethogram of individual social behaviours in rats.

Rats show a range of social behaviour, that is behaviours that are directly related to conspecifics, which can be split into socio-positive and socio-negative contexts. The ethogram is restricted to wild rats under natural or semi-natural conditions.

| Category | Behaviour | Sex | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-positive | Allogrooming | Females and males | One individual gently nibbles or licks the fur of a conspecific, sometimes with the aid of its forepaws. All body parts of the partner may be cleaned including the tail. | Barnett, 1963, p. 77 |

| Huddling | Females and males | Rats lie together with direct body contact, sometimes sleeping. | Barnett and Spencer, 1951; Barnett, 1963 | |

| Inspecting anogenital region | Females and males | One individual sniffs or licks the anogenital region of a conspecific, probably used in the context of recognition. | Barnett, 1963, p. 64 | |

| Nosing | Females and males | One individual gently pushes another’s flank or neck with its nose. | Barnett, 1963, p. 77 | |

| Nose-touching | Females and males | Two individuals approach each other until their noses come into contact. This possibly serves recognition and may result in socio-positive or negative behaviours. | Calhoun, 1979, p. 179 | |

| Oral inspection | Females and males | One individual sniffs at a conspecific’s mouth. This is most common between mothers and their offspring, but takes place between adults, too. | Calhoun, 1979, p. 149 | |

| Pioneering | Females and males | One individual leaves the burrow vigilantly and observes the surroundings for several minutes. Only then will other colony members appear from the burrow. | Barnett and Spencer, 1951; Telle, 1966 | |

| Play fighting | Females and males | One individual attacks the nape of its opponent, which the latter tries to defend. Play fights take place only during adolescence. | Ewer, 1971; Calhoun, 1979, p. 180 | |

| Recognition sniffing | Females and males | One individual shows enhanced sniffing at colony members and (potentially marked) objects, especially if a stranger entered its territory. | Barnett, 1967 | |

| Scent marking | Females and males | One individual rubs the flanks or presses the anogenital region on a surface, sometimes leaving urine droplets on the surface. | Landete-Castillejos, 1997 | |

| Sharing food | Females and males | An individual tolerates a conspecific in its close proximity, sometimes even touching each other, while feeding from the same food resource. Alternatively, one individual drops small food items that can be taken by another. Further, residues in the face or on the paws of an individual can be licked off by another. | Barnett and Spencer, 1951; Barnett, 1963, p. 36; Calhoun, 1979, p. 101 | |

| Submissive posture | Females and males | One individual lies on its side with eyes half-closed. This posture is used to ‘greet’ more dominant individuals to prevent fights. Sometimes this posture is combined with ‘crawling under’ (see below). | Barnett, 1967 | |

| Socio-negative | Aggressive grooming | Mostly males | One individual pins down a conspecific forcefully while allogrooming it. This is often accompanied by squeaks and run-away attempts of the groomed partner. | Barnett, 2001, p. 131 |

| Avoiding | Females and males | One individual changes its route upon detecting another rat. | Calhoun, 1979, p. 179 | |

| Boxing | Mostly males | Bouts of fights are typically intermitted by standing upright to box. While boxing, they hit and scratch each other’s face, which is accompanied with raised hair and ears pointing forward. | Barnett, 1963 | |

| Chasing | Females and males | One individual runs after a second. This usually precedes fights but can also take place afterwards. | Calhoun, 1979, p. 181 | |

| Crawling under/walking over | Mostly males | One rat crawls under, that is typically the subordinate, or walks over a conspecific, that is typically the more dominant. | Barnett, 1963 | |

| Direct approach | Mostly males | An individual approaches an opponent to attack, often accompanied with urination and defecation and raised hair. Sometimes the individual shows tooth chattering while approaching. | Barnett, 1963 | |

| Fighting | Mostly males | Two rats tumble, roll over the ground while holding, kicking and punching each other. | Barnett, 1963; Calhoun, 1979 | |

| Leaping and biting | Mostly males | The attacker jumps towards the opponent with extended forelimbs and tries to bite usually its ears, limb or tail. Bites are typically very quick. | Barnett, 1963 | |

| Passage guarding | Probably only males | One more dominant individual stands in a passage and therefore blocks the way of a second. The opponent typically waits until the first moves away or takes a detour. | Calhoun, 1979, p. 187 | |

| Pushing away | Females and males | One individual pushes another with its forepaws or flank to move a conspecific from its current position. Sometimes pushes are accompanied with kicks or swinging the body towards the opponent. | Calhoun, 1979, p. 101 | |

| Tail quivering | Females and males | One individual quivers its tail, which might be shown in various situations like during ‘crawling under’ or shortly before copulation. | Steininger, 1950 | |

| Threat posture | Mostly males | An attacker adopts a posture where the back is maximally arched, all limbs are extended, and the flank is turned to its opponent. | Barnett, 1963 | |

| Tooth-chattering | Females and males | One individual chatters with its teeth while staying immobile, most common after detecting an opponent. | Barnett, 1963 |

Overview of studies showing cooperative behaviour in rats.

Rats are highly social animals that have been shown multiple times to cooperate, i.e. one individual benefits one or more other individuals (Sachs et al., 2004). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain why they cooperate. Domesticated, wild and wild-derived rats of both sex were tested in a variety of tasks, involving various behaviours to measure their tendency to cooperate.

| Proposed mechanism | Cooperative behaviour | Sex of test subjects | Origins of test subjects | Task | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessing the other’s need in a helping task | Simultaneous nose-poking | Males | Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley) | Skinner box | Łopuch and Popik, 2011 |

| Entering one compartment, which leads to food rewards | T maze | Márquez et al., 2015 | |||

| Donating food by pulling it into the reach of a partner | Females | Wild-derived | Bar pulling task | Schneeberger et al., 2012; Schweinfurth and Taborsky, 2018b | |

| Coordination (acting together) | Coordinating back and forth shuttling | Females and males | Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley) | T-maze | Daniel, 1942 |

| Swanson and Schuster, 1987 | |||||

| Domesticated (S3, Sprague-Dawley and Wistar) | Schuster et al., 1993 | ||||

| Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley and S3) | Schuster et al., 1988 | ||||

| Males | Domesticated (Long Evans) | Tan and Hackenberg, 2016 | |||

| Division of labour (sharing of tasks) | Tolerating thefts | Females and males | Domesticated (Wistar) | Diving for food | Colin and Desor, 1986; Krafft et al., 1994; Grasmuck and Desor, 2002 |

| Donating food by pushing down a lever | Males | Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley) | Skinner box | Littman et al., 1954 | |

| Empathy (ability to perceive and care for the emotional states of others) Or: social contact seeking | Freeing trapped partners by opening a door | Females and males | Domesticated (Wistar) | Partner trapped in container | Rice and Gainer, 1962 |

| Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley) | Ben-Ami Bartal et al., 2011 | ||||

| Males | Ben-Ami Bartal et al., 2016 | ||||

| Silberberg et al., 2014 | |||||

| Females and males | Partner trapped in a pool | Sato et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2017 | |||

| Females | Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley and Long-Evans) | Partner trapped in container | Ben-Ami Bartal et al., 2014 | ||

| Inequity aversion (preference of equal outcomes) | Entering one compartment, which leads to food rewards | Males | Domesticated (Long- Evans) | T-maze | Oberliessen et al., 2016 |

| Prosociality (preference to provide benefits to others) | Entering one compartment, which leads to food rewards | Males | Domesticated (Long- Evans) | T-maze | Hernandez-Lallement et al., 2014, Hernandez-Lallement et al., 2016 |

| Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley) | Márquez et al., 2015 | ||||

| Reciprocity (conditional help based on previous received help) | Allogrooming | Females | Wild-derived | Direct interactions | Schweinfurth et al., 2017b |

| Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley) | Yee et al., 2008 | ||||

| Donating food by pulling it into the reach of a partner | Males | Wild-derived | Bar pulling task | Schweinfurth et al., 2019: Schweinfurth and Taborsky, 2018a | |

| Donating food by pushing down a lever | Domesticated (Long-Evans) | Skinner box | Li and Wood, 2017 | ||

| Entering one compartment, which leads to rewards | Domesticated (Sprague-Dawley) | T maze | Simones, 2007; Viana et al., 2010 | ||

| Donating food by pushing down a lever | Females and males | Domesticated (Long-Evans) | Skinner box | Li and Wood, 2017 | |

| Donating food by pulling it into the reach of a partner | Females | Wild-derived | Bar pulling task | Rutte and Taborsky, 2007; Rutte and Taborsky, 2008; Dolivo and Taborsky, 2015a; Schweinfurth and Taborsky, 2016 | |

| Reciprocity between different commodities | Donating food by pulling und pushing it into the reach of a partner | Females | Wild-derived | Bar pulling and lever pressing task | Schwartz et al., 2017 |

| Allogrooming and donating food by pulling it into the reach of a partner | Direct interaction and bar pulling task | Stieger et al., 2017; Schweinfurth and Taborsky, 2018c | |||

| Warning | Alarm calling | Females and males | Domesticated (Long- Evans and Wistar) | Cat exposure | Blanchard and Blanchard, 1989; Blanchard et al., 1991 |

| Playback | Sales, 1991 | ||||

| Males | Domesticated (Wistar) | Brudzynski and Chiu, 1995 |