Sex-specific effects of cooperative breeding and colonial nesting on prosociality in corvids

Figures

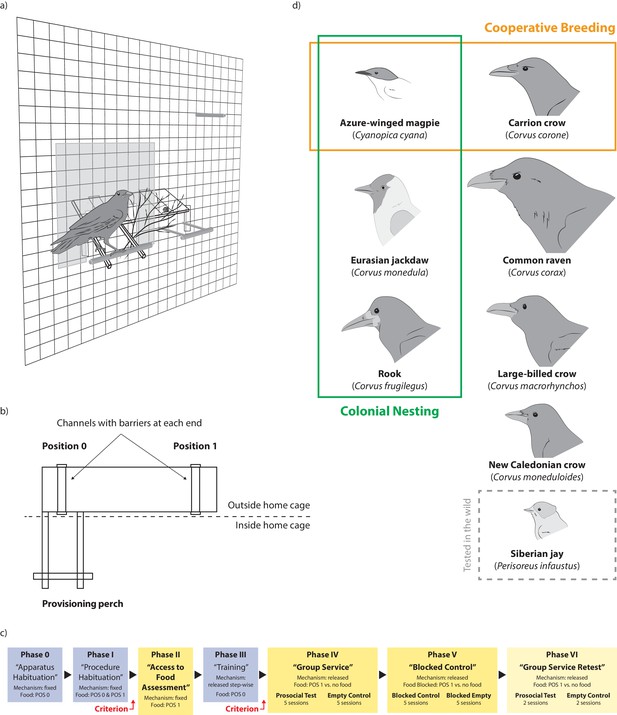

Overview of the study design and set-up.

(a) Experimental set-up as seen from the inside of the aviary with a bird sitting on the provisioning perch, thereby making food available to the group. (b) Schematic of the apparatus with location of positions 0 and 1 in relation to the provisioning perch. (c) Experimental procedure; habituation and training phases are given in blue, test phases are given in yellow; subjects needed to reach a given criterion to be included in the analysis of phases II and IV-VI; see supplementary information for details. (d) Overview of the tested species and their key social system differences; orange boxes represent the presence of obligate or facultative cooperative breeding for the respective species, green boxes represent the presence of colonial nesting.

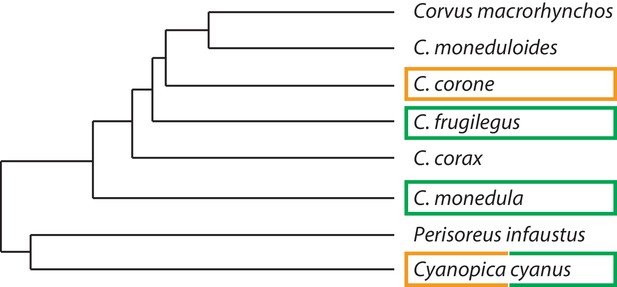

Phylogenetic tree of the tested species.

Phylogenetic relationships were taken from an analysis of 34 corvid species based on DNA sequences of the mitochondrial control region (Haring et al., 2012). Orange boxes represent the presence of obligate or facultative cooperative breeding for the respective species, green boxes represent the presence of colonial nesting.

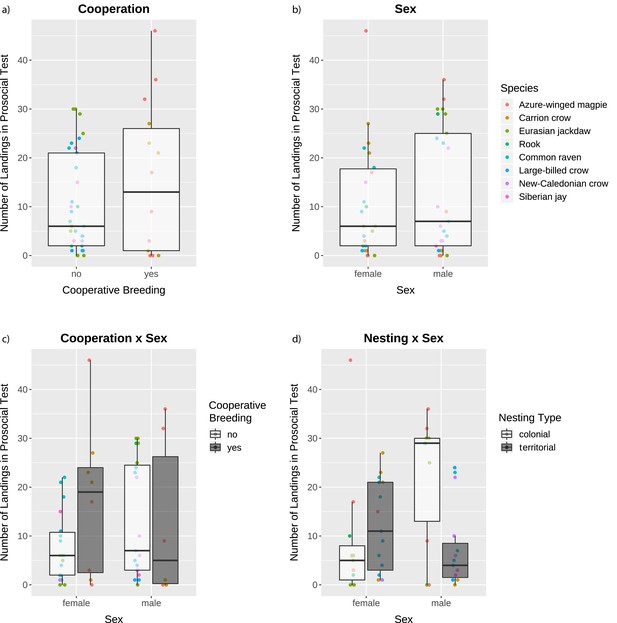

Number of landings in the prosocial test as a function of the factors with a high explanatory degree.

The box plots represent medians (horizontal lines), inter-quartile ranges (boxes), as well as minima and maxima (whiskers). All data are represented with dots. Dots not encompassed by the whiskers are outliers. Dot colors in all panels indicate the species according to the legend in the top right panel.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Effects of cooperative breeding, nesting type, and sex on the number of landings in the prosocial test.

Given are estimates, standard errors (SE), z-values, sum of AICc weights (SWAICc), and number of models containing the specific factor (NModels) after model averaging. Factors with a sum of AICc weights larger than 0.5 and whose SE of the estimates did not overlap 0 were considered to have a high explanatory degree and are given in bold. Number of individuals: N = 51.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/58139/elife-58139-fig2-data1-v2.docx

-

Figure 2—source data 2

Effects of cooperative breeding and nesting type on the number of landings in the prosocial test in female birds (A) and male birds (B).

Given are estimates, standard errors (SE), z-values, sum of AICc weights (SWAICc), and number of models containing the specific factor (NModels) after model averaging. Factors with a sum of AICc weights larger than 0.5 and whose SE of the estimates did not overlap 0 were considered to have a high explanatory degree and are given in bold.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/58139/elife-58139-fig2-data2-v2.docx

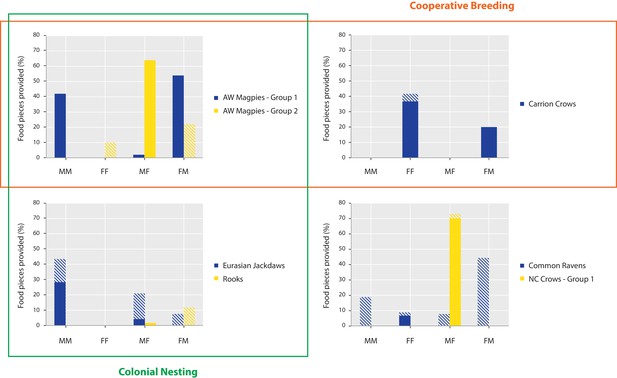

Distribution of food provisioning per dyad sex composition.

The bars represent the percentage of food provided in the last two test sessions of the prosocial test in those seven groups where provisioning occurred and for which we had data on the individuals’ sex and the dyad identities. Full bars comprise the individuals that passed the criterion of landing significantly more in the test versus both control conditions. Striped bars comprise all individuals. Dyad types: male donor – male recipient (MM), female donor – female recipient (FF), male donor – female recipient (MF), female donor – male recipient (FM). All possible dyads: azure-winged magpies, group 1, 3 MM, 1FF, 6MF/FM; azure-winged magpies, group 2, 0 MM, 3FF, 3MF/FM; carrion crows, 1 MM, 6FF, 8MF/FM; Eurasian jackdaws, 21 MM, 21FF, 49MF/FM; rooks 15 MM, 15FF, 36MF/FM; common ravens, 6 MM, 10FF, 20MF/FM; New Caledonian crows, group 1, 1 MM, 0FF, 2MF/FM.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Data on food provisioning per dyad sex composition.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/58139/elife-58139-fig3-data1-v2.xlsx

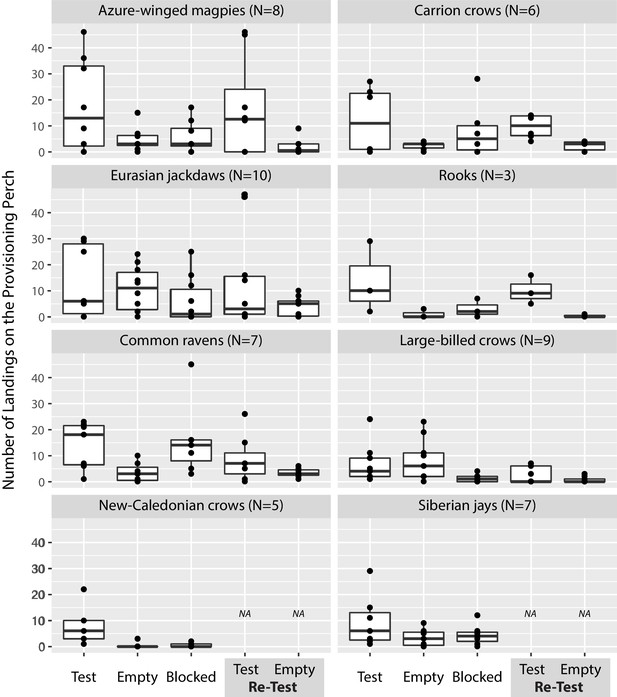

Number of landings in all test phases, split by species.

The box plots represent medians (horizontal lines), inter-quartile ranges (boxes), as well as minima, maxima (whiskers). All data are represented with dots. Dots not encompassed by the whiskers are outliers. NA = not available.

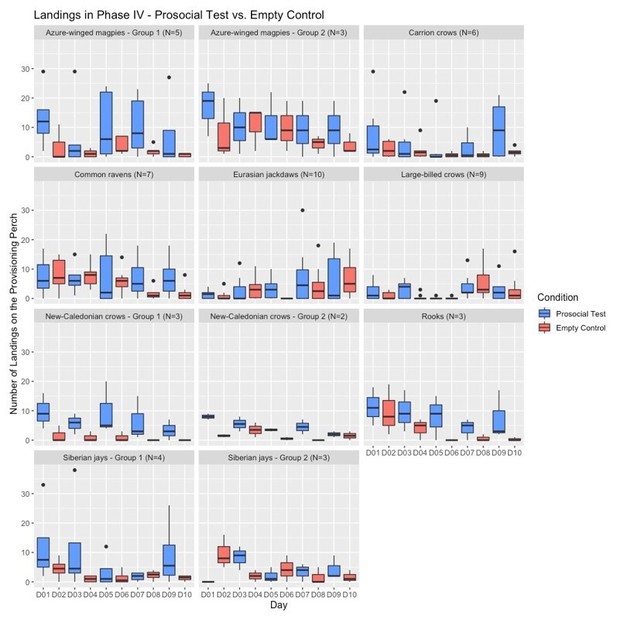

Number of landings across the testing days of Phase IV (prosocial test vs empty control) for all groups.

The box plots represent medians (horizontal lines), inter-quartile ranges (boxes), as well as minima, maxima (whiskers). Dots not encompassed by the whiskers are outliers.

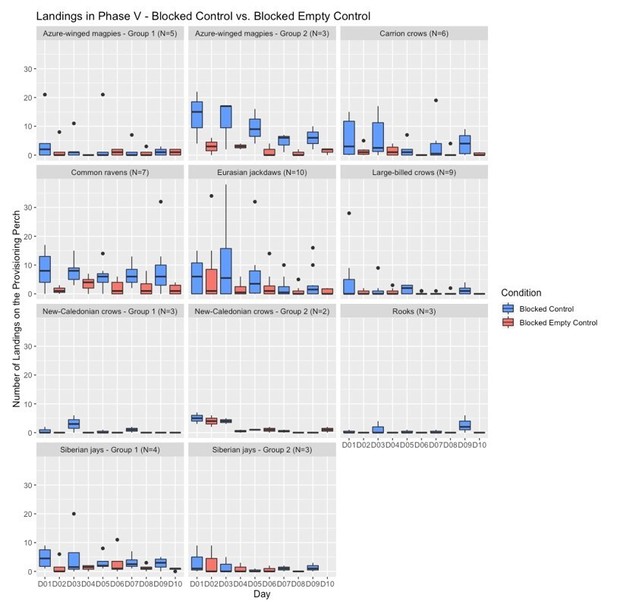

Number of landings across the testing days of Phase V (blocked control vs blocked empty control) for all groups.

The box plots represent medians (horizontal lines), inter-quartile ranges (boxes), as well as minima, maxima (whiskers). Dots not encompassed by the whiskers are outliers.

Videos

Prosocial test.

Example videos of prosocial test trials taken from three species (i.e. azure-winged magpies, carrion crows, common ravens). Food is placed on the recipient side (position 1). Food can be provided to a group member, if an individual lands on the provisioning perch.

Empty control.

Example videos of empty control trials taken from three species (i.e. azure-winged magpies, carrion crows, common ravens). No food is placed on the recipient side (position 1). Therefore, no food can be provided to group members.

Blocked control.

Example videos of blocked control trials taken from three species (i.e. azure-winged magpies, carrion crows, common ravens). Food is placed on the recipient side (position 1), but access to the food is blocked with a fine net. Therefore, although food is visible, no food can be provided to the group members.

Tables

Prosocial food provisioning and evenness of access to food across all tested species and groups.

Given are the classifications of cooperative breeding and nesting type for the tested species, as well as the percentage of food provided in the prosocial test and Pielou’s J’ as a measure for evenness of access to food for each of the groups.

| Species | Cooperative breeding* | Nesting type† | Group (N) | Phase IV provided food‡ | Phase II Pielou’s J’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azure-winged magpie | Yes | Colonial | 1 (5) | 98% | 0.72 |

| 2 (4) | 64% | 0.83 | |||

| Carrion crow | yes | Territorial | 1 (6) | 57% | 0.46 |

| Eurasian jackdaw | no | Colonial | 1 (14) | 33% | 0.73 |

| Rook | no | Colonial | 1 (12) | 2% | 0.86 |

| New-Caledonian crow | no§ | Territorial | 1 (3) | 70% | 0.52 |

| 2 (2) | 0% | 0.36 | |||

| Common raven | no | Territorial | 1 (9) | 21% | 0.73 |

| Large-billed crow | no | Territorial | 1 (9) | 16% | 0.97 |

| Siberian jay | no | Territorial | 1 (5) | 0% | 0.82 |

| 2 (3) | 0% | 0.91 |

-

*Classifications after (Cockburn, 2006).

†Classifications after (Madge and Burn, 1999).

-

‡In line with the original publication (Burkart et al., 2014), provided food was calculated as the corrected percentage of food provisioning per group in the last two test sessions of the prosocial test, only by those individuals that passed the criterion of landing significantly more often in the test compared to both control conditions. Note that raw and corrected measures of food provisioning are highly correlated (Spearman’s rho = 0.892, p≤0.001, N = 11).

§Occurrence of cooperative breeding is classified as unknown, but assumed as absent according to Cockburn, 2006.

Group size and number of individuals passing the selection criteria across all tested groups.

Given are – for each group – the group size and the number of birds passing the criteria for phases II and IV (i.e. taking at least 10 pieces of food in a minimum of five sessions in the previous phase) and the criterion of landing in significantly more trials in the prosocial test than in both the empty and the blocked control (Fisher’s exact test).

| Species | Group | Group size | Criterion Phase II | Criterion Phase IV | Criterion test vs. controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Sessions, median (min, max) | N | Sessions, median (min, max) | ||||

| Azure-winged magpies | 1 | 5 | 5 | 9 (6, 11) | 5 | 23 (22, 30) | 3 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | 7.5 (5, 12) | 3 | 33 (33, 49) | 1 | |

| Carrion crows | 1 | 6 | 6 | 9 (5, 13) | 6 | 11 (9, 17) | 2 |

| Rooks | 1 | 12 | 5 | 10 (5, 17) | 3 | 65 (65, 65) | 1 |

| Eurasian jackdaws | 1 | 14 | 12 | 26 (5, 51) | 10 | 59 (58, 65) | 2 |

| New-Caledonian crows | 1 | 3 | 3 | 8 (8, 8) | 3 | 17 (16, 18) | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 (5, 5) | 2 | 13 (12, 14) | 0 | |

| Common ravens | 1 | 9 | 9 | 7 (5, 26) | 7 | 30 (27, 37) | 1 |

| Large-billed crows | 1 | 9 | 9 | 5 (5, 6) | 9 | 10 (10,12) | 1 |

| Siberian jays | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 (5, 9) | 4 | 5 (5, 5) | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 (5, 5) | 3 | 10 (10, 10) | 0 | |

Effects of cooperative breeding, nesting type and sex on the number of landings in the prosocial test.

Given are estimates, standard errors (SE), z-values, sum of AICc weights (SWAICc), and number of models containing the specific factor (NModels) after model averaging. Factors with a sum of AICc weights larger than 0.5 and whose SE of the estimates did not overlap 0 were considered to have a high explanatory degree and are given in bold. Number of individuals: N = 51.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Z | SWAICc | NModels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 6.403 | 3.739 | 1.675 | - | - |

| Cooperation (yes) | 10.024 | 4.226 | 2.304 | 0.61 | 1 |

| Nesting (territorial) | 4.092 | 4.073 | 0.977 | 1.00 | 2 |

| Sex (male) | 17.075 | 5.672 | 2.947 | 1.00 | 2 |

| Cooperation (yes) x Sex (male) | −16.057 | 6.445 | 2.420 | 0.61 | 1 |

| Nesting (territorial) x Sex (male) | −19.611 | 6.014 | 3.172 | 1.00 | 2 |

Threshold for model selection and averaging set to delta AICc ≤ 7.

Given are estimates, standard errors (SE), z-values, sum of AICc weights (SWAICc), and number of models containing the specific factor (NModels) after model averaging. Factors with a sum of AICc weights larger than 0.5 and whose SE of the estimates did not overlap 0 were considered to have a high explanatory degree and are given in bold. Number of individuals: N = 51.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Z | SWAICc | NModels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 6.836 | 5.400 | 1.240 | - | - |

| Cooperation (yes) | 9.201 | 5.877 | 1.534 | 0.73 | 10 |

| Nesting (territorial) | 3.974 | 4.859 | 0.799 | 0.97 | 12 |

| Sex (male) | 17.192 | 5.954 | 2.829 | 0.93 | 10 |

| Cooperation (yes) x Sex (male) | −16.199 | 7.035 | 2.240 | 0.59 | 5 |

| Nesting (territorial) x Sex (male) | −19.698 | 6.429 | 2.985 | 0.93 | 10 |

| Cooperation (yes) x Nesting (territorial) | −3.984 | 7.676 | 0.505 | 0.17 | 4 |

| Group size | −0.154 | 0.594 | 0.253 | 0.19 | 4 |

| Cooperation (yes) x Nesting (territorial) x Sex (male) | 0.902 | 14.106 | 0.062 | 0.02 | 1 |

Effects of cooperative breeding, nesting type and sex on the number of landings in the prosocial test without the Siberian jays.

Given are estimates, standard errors (SE), z-values, sum of AICc weights (SWAICc), and number of models containing the specific factor (NModels) after model averaging. Factors with a sum of AICc weights larger than 0.5 and whose SE of the estimates did not overlap 0 were considered to have a high explanatory degree and are given in bold. Number of individuals: N = 48.

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Z | SWAICc | NModels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 6.105 | 3.989 | 1.495 | - | |

| Cooperation (yes) | 10.317 | 4.637 | 2.161 | 0.67 | 1 |

| Nesting (territorial) | 3.835 | 4.439 | 0.839 | 1.00 | 2 |

| Sex (male) | 17.640 | 6.059 | 2.848 | 1.00 | 2 |

| Cooperation (yes) x Sex (male) | −16.783 | 7.064 | 2.308 | 0.67 | 1 |

| Nesting (territorial) x Sex (male) | −18.678 | 6.574 | 2.763 | 1.00 | 2 |

Effects of cooperative breeding, nesting type, and sex on the number of landings in the prosocial test in a phylogenetically controlled model.

Given are the posterior mean of the estimate (Post. mean), its 95% credible interval (95% HPD interval), its effective sample size (Eff. samp.), and p-value (PMCMC) of each parameter. Number of individuals: N = 51. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001.

| Parameter | Post. mean | 95% HPD interval | Eff. samp. | PMCMC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 5.012 | [−3.198, 13.247] | 10111 | 0.210 |

| Cooperation (yes) | 10.001 | [0.082, 19.886] | 9998 | 0.048* |

| Nesting (Territorial) | 4.346 | [−5.408, 13.376] | 9998 | 0.347 |

| Sex (male) | 19.660 | [8.899, 30.292] | 9998 | 0.0002*** |

| Cooperation (yes) x Sex (male) | −20.576 | [−33.588,–8.551] | 9998 | 0.002** |

| Nesting (territorial) x Sex (male) | −16.394 | [−30.183,–2.329] | 9998 | 0.020* |

Percentage of motivation trials with landings.

Given are – for each group – the number of motivation trials in the last two sessions of each condition and the percentage of motivation trials in which any bird landed on the provisioning perch, as well as the median, minimum and maximum of these percentages. NA = not available, min = minimum, max = maximum.

| Species | Group | Motivation trials (N) | Test | Empty | Blocked | Re-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Empty | ||||||

| Azure-winged magpies | 1 | 12 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 2 | 12 | 92 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Carrion crows | 1 | 14 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 | 100 |

| Rooks | 1 | 14 | 100 | 100 | 79 | 93 | 93 |

| Eurasian jackdaws | 1 | 26 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Common ravens | 1 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Large-billed crows | 1 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 55 |

| New-Caledonian crows | 1 | 8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | NA | NA |

| 2 | 6 | 83 | 83 | 100 | NA | NA | |

| Siberian jays | 1 | 12 | 75 | 83 | 83 | NA | NA |

| 2 | 8 | 75 | 88 | 50 | NA | NA | |

| Median (min, max) | 100 (75, 100) | 100 (83, 100) | 100 (50, 100) | 100 (93, 100) | 100 (55, 100) | ||

Study sites, subject and husbandry details, testing period, and ethical approval information.

| Species | Study site | Subject and husbandry details | Testing period | Ethical approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azure-winged magpies (Cyanopica cyana) Group 1 | Haidlhof Research Station, University of Vienna and University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Austria | Subjects: two females, three males; all birds were adults and parent-raised. Housing: outdoor aviary (5 × 3×3 m), partially covered with a semi-transparent roof; the aviary used fine-grained sand as substrate and was equipped with fixed and swinging branches, live plants, stones, woodchips and gravel for caching food, a birdbath, and other enrichment objects. Feeding: the birds were fed daily with different fruits, insects, and seeds; water and pellets (‘Beo komplet’, NutriBird) were provided ad libitum; vitamin supplements and meat or egg were provided every second week. | Apr – Nov 2015; re-test: Apr 2016 | All animal care and data collection protocols were approved by the Animal Welfare Board of the Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna (permit no. 2016–008). |

| Azure-winged magpies (Cyanopica cyana) Group 2 | Animal Care Facility of the Department of Cognitive Biology, University of Vienna, Austria | Subjects: two adult females, one adult male, one juvenile female (<1 year old); all birds were parent-raised. one additional juvenile bird was housed in the same aviary, but never participated in the experiment due to physical impairments. Housing: outdoor aviary (6 × 3×3 m), fully covered with a semi-transparent roof; for equipment see group 1. Feeding: see group 1 | Nov 2015 – Apr 2016; re-test: May 2016 | All animal care and data collection protocols were approved by the Animal Welfare Board of the Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna (permit no. 2016–008). |

| Carrion crows (Corvus corone) | Haidlhof research station, University of Vienna and university of veterinary medicine vienna, Austria | Subjects: four females, two males; all birds were adults and hand-raised. By appearance, the crows were either carrion crows or hybrids of carrion and hooded crows, reflecting the hybridization belt in Europe. Both species have highly similar life histories and are often considered to belong to one species complex (Vijay et al., 2016). Housing: the aviary comprised a large outdoor part (12 × 9 × 5 m) and two adjacent roofed experimental compartments (3 × 4 × 5 m each); the aviary used coarse sand as substrate and was equipped with fixed and swinging branches, live plants, stones, woodchips and gravel for caching food, several birdbaths, and other enrichment objects. Feeding: the birds were fed a diverse diet containing meat, milk products, cereal, vegetables, and fruit twice a day; water was provided ad libitum. | Oct 2015 – May 2016; re-test: Jul 2016 | All animal care and data collection protocols were approved by the Animal welfare board of the faculty of life sciences, University of Vienna (permit no. 2016–017). |

| Common ravens (Corvus corax) | Haidlhof Research Station, University of Vienna and University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Austria | Subjects: three adult birds (>4 years old; 1F/2M), six subadult birds (2 years old; 4F/2M); all birds were hand-raised. Housing: large outdoor aviary (15 × 15×5 m) that could be divided into several compartments; equipment see carrion crows. Feeding: see carrion crows. | May – Oct 2016; re-test: Nov 2016 | All animal care and data collection protocols were approved by the Animal Welfare Board of the Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna (permit no. 2016–017). |

| Large-billed crows (Corvus macrorhynchos) | Tsukuba Field Station, Keio University, Japan | Subjects: nine sub-adult birds (all were 3 years old; 4F and 5M); all birds were parent-raised and born in the wild. They were caught as free-floating yearlings in the wild and group-housed thereafter. Housing: outdoor aviary (10 × 10 × 3 m) that could be divided four experimental compartments (5 × 5×3 m); the aviary used coarse sand as substrate and was equipped with large branches, a water pool for bathing and other enrichment objects. Feeding: Dairy diet consisted of dog food, meat, eggs, dried fruits. Water was available ad libitum. | May – Jul 2016; re-test: Dec 2016 | Animal Care and Use Committee of Keio University (no. 16059) |

| New-Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides) Group 1 | La Foa, Province Sud, New Caledonia | Subjects: two adult birds (>3 years old; 1F and 1M) and one juvenile bird (1 st year; M); family group; all were wild caught, temporarily housed and released in the wild. Housing: Crows were housed in an outdoors aviary for temporary behavioral research purposes before being released back into the wild. Feeding: Daily diet consisted of meat, dog food, eggs, and fresh fruit, with water available ad libitum. | Jun – Jul 2017 | University of Auckland Animal Ethics Committee (reference no. 001823). |

| New-Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides) Group 2 | La Foa, Province Sud, New Caledonia | Subjects: one adult bird (>3 years old; M) and one juvenile bird (1 st year; M); father and son dyad; both were wild caught, temporarily housed and released in the wild. Housing: see group 1 Feeding: see group 1 | May – Jul 2016 | University of Auckland Animal Ethics Committee (reference no. 001823). |

| Rooks (Corvus frugilegus) | ‘Eulen- und Greifvogelstation’, Haringsee, Austria | Subjects: 10 adult birds (5F/5M), two subadult birds (1F/1M); all birds were parent-raised and born in the wild. Housing: outdoor aviary (3.3 × 7.4 × 3.1 m) with a roofed platform (3.3 × 1.1 m); the aviary used soil and bark chips as substrate and was equipped with large branches, a water pool for bathing and other enrichment objects. Feeding: the birds were fed on a daily basis with cereals, dried mealworms, minced meat mixed with calcium carbonate and small pieces of scrambled eggs; water was provided ad libitum; nuts and chicks were provided several times a week. | May 2016 – Mar 2017; re-test: Jun 2017 | All animal care and data collection protocols were approved by the Animal Welfare Board of the Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna (permit no. 2016–017). |

| Siberian jays (Perisoreus infaustus) Group 1 | Wild population, studied near Arvidsjaur, Swedish Lapland (65°40 N, 19°0 E) | Subjects: male breeder, two non-breeders born in spring 2017, two juveniles born in spring 2018; one subject did not participate in phase 4; all individuals are members of a wild group of Siberian jays, part of a long-term study on individually color-ringed Siberian jays (see Ekman & Griesser 2016). Living area: The study was carried out in a natural setting in a wild population, thus the birds required no care. The apparatus was placed within the focal group’s territory. We provided less preferred food (pig fat) on a standardized feeding device on the side of the experimental apparatus to keep the group near the apparatus. | Sept – Oct 2018 (Experiments were carried out when the birds engage in storing food for winter) | Experiments approved by Umea ethics board, A39-15. Ringing under the license of the Swedish Museum of Natural History. |

| Siberian jays (Perisoreus infaustus) Group 2 | Wild population, studied near Arvidsjaur, Swedish Lapland (65°40 N, 19°0 E) | Subjects: male and female breeder, one juvenile born spring 2018. Living area: See above for details. | Sept – Oct 2018 (Experiments were carried out when the birds engage in storing food for winter) | Experiments approved by Umea ethics board, A39-15. Ringing under the license of the Swedish Museum of Natural History. |

| Eurasian jackdaws (Corvus monedula) | Comparative Cognition Research Group of the Max-Plank-Institute for Ornithology in Seewiesen, Germany | Subjects: 7 males and seven females adult birds (>4 years old), most of the birds were hand-raised. one subject (male) participated only in phases 0–2; one subject (female) only participated in phases 0–3. two subjects (1 male and one female) joined the group in June 2017 and participated in phases 3–6. Housing: the birds had access to two aviaries (aviary 1: 15m × 9 m × 2.80 m; aviary 2: 12m × 10 m × 2.80 m) with adjacent experimental compartments. All compartments had natural soil and vegetation, including bushes and small trees, and were equipped with breeding boxes, several birdbaths, and other enrichment objects. Feeding: the birds were fed a diverse diet consisting of meat, insects, curd, rice, cereals and Versele Laga Nutribird Beo pearls, and fruit twice a day; water was provided ad libitum. The food was enriched with mineral and vitamin supplements. | Aug 2016 – Aug 2017; re-test: Sep 2017 | The study followed the protocols of the University of Vienna and followed the guidelines of the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour and conformed the European and German legalisations and guidelines for the use of animals. All animals were habituated to humans. |

Additional files

-

Source code 1

Source code for the calculation of Pielou's J' and for running the statistical models in R.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/58139/elife-58139-code1-v2.zip

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/58139/elife-58139-transrepform-v2.pdf