Cardiovascular disease risk factors induce mesenchymal features and senescence in mouse cardiac endothelial cells

Figures

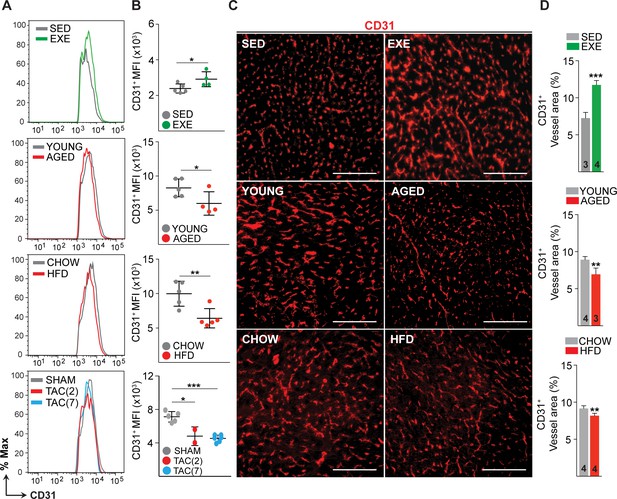

Effects of exercise training, aging, obesity, and pressure overload on cardiac endothelial cell (EC) number and vascular density.

(A and B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis and quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cardiac ECs (CD31+CD140a-CD45-Ter119-DAPI-) in various mouse models. (C and D) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of CD31+ blood vessel area (%) in the heart. Scale bar 100 μm. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. In panel (B), each color-coded circle indicates an individual biological sample. In panel (D), the number of mice in each experimental group is indicated in the respective graph, N = 3–5 male mice/group.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Source data for Figure 1B and D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig1-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 1—source data 2

Echocardiography measurements of cardiac function and ventricular dimensions in the indicated experimental group.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig1-data2-v2.pdf

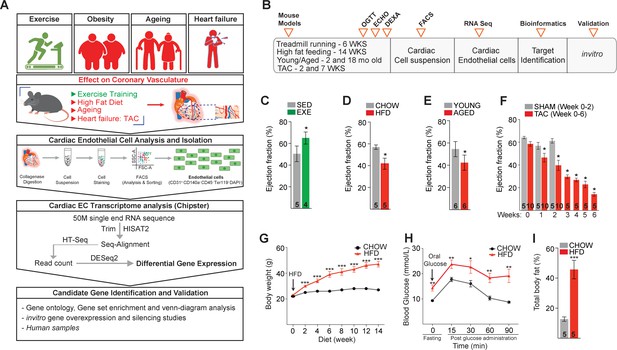

Schematic of the experimental set-up to elucidate the impact of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors on cardiac endothelial cell (EC) transcriptome and the validation of the experimental CVD risk factor models.

(A) Experimental workflow demonstrating the mouse models used to mimic CVD risk factors in C57Bl/6J mice, analysis and isolation of cardiac ECs by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, bioinformatic analyses of the cardiac EC transcriptome, and identification and validation of candidate genes using human ECs and heart tissue. (B) Experimental timeline of exercise training (6 weeks of treadmill running), high-fat diet (HFD; 14 weeks of high-fat feeding), physiological aging (18 months old), and pressure overload-induced heart failure by transaortic constriction in mice. (C–F) Ejection fraction in each of the four experiments. (G) Body weight (g) during the HFD experiment. (H) Blood glucose levels during oral glucose tolerance test (mmol/L), and (I) total body fat (%) measured after 14 weeks of HFD. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (in panels C–F and I, the number of mice in each experimental group is indicated in the respective graphs; in panels G–H, N = 4–5 male mice/group were analyzed).

-

Figure 1—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Source data for Figure 1—figure supplement 1C, D, E, F, G, H and I.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig1-figsupp1-data1-v2.xlsx

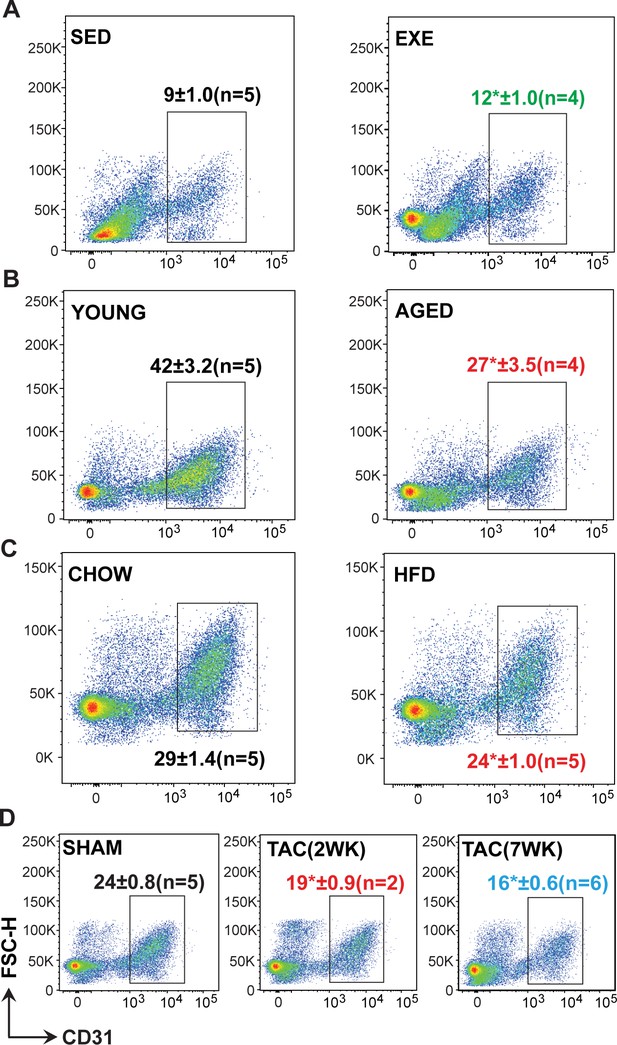

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of cardiac endothelial cell (EC).

(A–D) Representative pseudocolor FACS plots showing the gating and percentage of cardiac ECs (CD31+ CD140a- CD45- Ter119- DAPI-) in the different treatment groups. In panels (A–D), the number of male mice in each experimental group is indicated in the respective FACS plots.

-

Figure 1—figure supplement 2—source data 1

Source data for Figure 1—figure supplement 2A, B, C and D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig1-figsupp2-data1-v2.xlsx

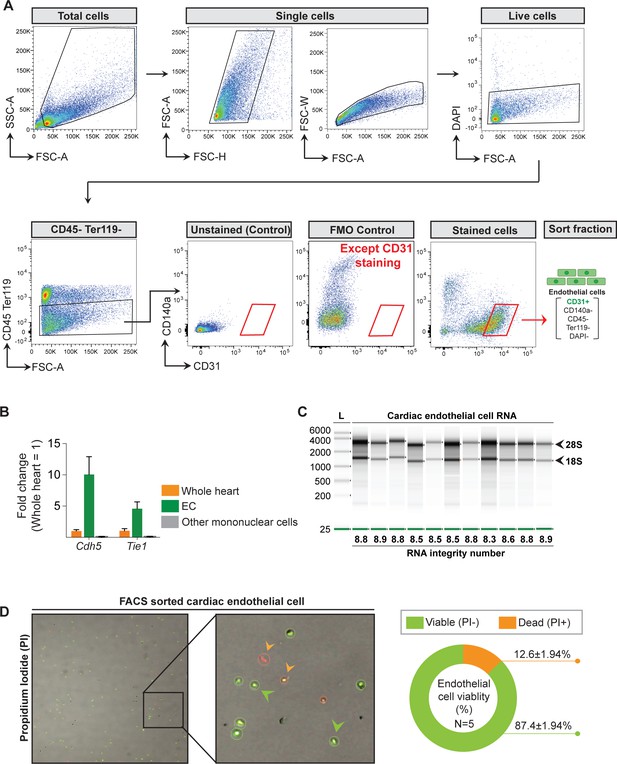

Quality metrics of the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) sorted cardiac endothelial cell (EC).

(A) Gating strategy to sort cardiac ECs (CD31+ CD140a- CD45- Ter119- DAPI-). (B) Purity analysis of the post sort EC fraction by QPCR (N = 3–4 male mice/group were analyzed). (C) Representative image of the bioanalyzer data showing the RNA integrity number (RIN) values of the isolated RNA. (D) Mononuclear cells and pie chart of the post sort EC fraction showing viable cells in green and dead cells in red (N = 5 male mice/group were analyzed).

-

Figure 1—figure supplement 3—source data 1

Source data for Figure 1—figure supplement 3B.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig1-figsupp3-data1-v2.xlsx

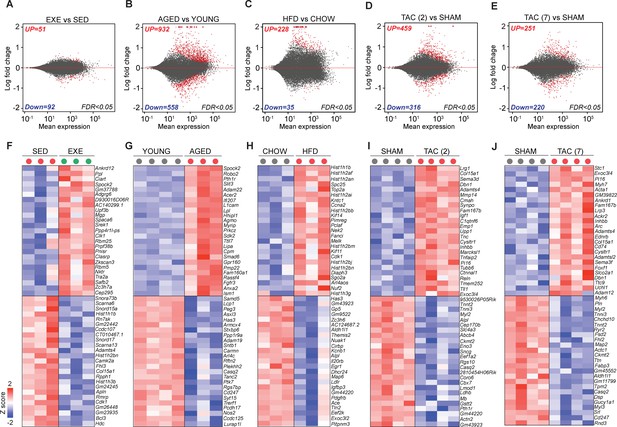

Transcriptomic changes in cardiac endothelial cells (ECs) in exercise trained, aged, obese, and transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-treated mice.

(A–E) MA-plots (log ratio over mean) showing the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in cardiac ECs for each experiment. Number of significantly up- and downregulated genes with the false discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value) threshold of 0.05 are indicated in the plots. (F–J) Top 50 DEGs in cardiac ECs of the indicated experimental groups. In the heatmap, each color-coded circle (red, green, and black) indicates an individual biological sample within each experimental group. N = 3–4 male mice/group.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Source data for Figure 2F, G, H, I and J.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig2-data1-v2.xlsx

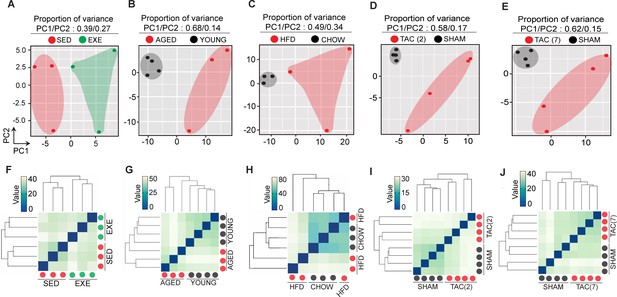

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot and unsupervised hierarchical clustering of cardiac endothelial cell transcriptome from exercise trained, aged, obese, and transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-treated mice.

(A–E) Two-dimensional PCA. (F–J) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of cardiac endothelial transcriptome in the indicated experimental groups. Each color-coded circle (red, green, and black) in the PCA and unsupervised clustering plot indicate one biological sample and N = 3–4 male mice/experimental condition were analyzed.

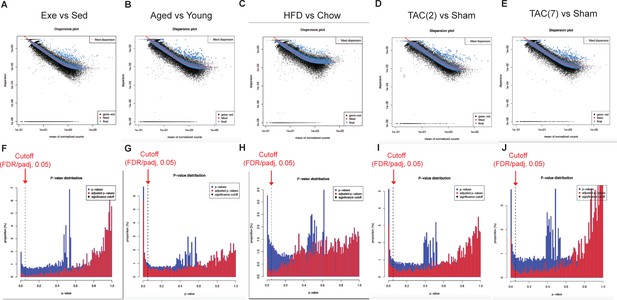

Dispersion mean plot and p-value distribution plot of the indicated RNA sequencing experiments.

(A–E) Plot of dispersion estimates at different count levels, showing black dot (dispersion estimate for each gene as obtained by considering the information from each gene separately), red line (fitted estimates showing the dispersions' dependence on the mean), blue dot (the final dispersion estimates shrunk from the gene-wise estimates toward the fitted estimates. The values are used for further statistical testing). Blue circles are genes which have high gene-wise dispersion estimates and are hence labeled dispersion outliers and not shrunk toward the fitted trend line. (F–J) Plot of the raw p-value (Wald test) indicated in blue bars and the false discovery rate (FDR) distribution or adjusted p-value (Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value) of the statistical test. The arrow indicates cutoff point FDR threshold of 0.05 and the genes with FDR values less than or equal to the cutoff points were used for further analysis.

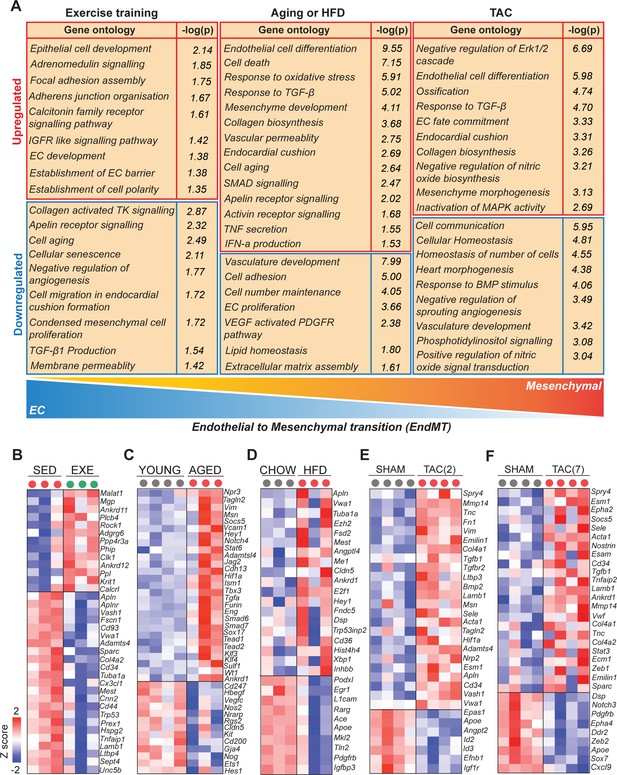

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors activate mesenchymal gene expression in cardiac endothelial cells (ECs).

(A) Gene ontology analysis of the up- and downregulated genes. Note the opposite changes induced by exercise training compared to the CVD risk factors. (B–F) Heatmaps showing the differential gene expression of endothelial and mesenchymal genes previously associated with endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT). Genes are selected based on published data sets (references are found in Figure 3—source data 1). In all panels, the up- and downregulated genes with the false discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value) threshold of 0.05 were considered. In the heatmap, each color-coded circle (red, green, and black) indicates an individual biological sample within each experimental group. N = 3–4 male mice/group.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Genes and reference list for endothelial and mesenchymal genes indicated in the Figure 3B–F heat map.

(A) Reference list for endothelial and mesenchymal genes indicated in the Figure 3B (EXE vs. SED) heat map. (B) Reference list for endothelial and mesenchymal genes indicated in the Figure 3C (aged vs. young) heat map. (C) Reference list for endothelial and mesenchymal genes indicated in the Figure 3D (high-fat diet [HFD] vs. Chow) heat map. (D) Reference list for endothelial and mesenchymal genes indicated in the Figure 3E (transverse aortic constriction [TAC] [2] vs. Sham) heat map. (E) Reference list for endothelial and mesenchymal genes indicated in the Figure F (TAC [7] vs. Sham) heat map.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig3-data1-v2.docx

-

Figure 3—source data 2

Source data for Figure 3B, C, D, E and F.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig3-data2-v2.xlsx

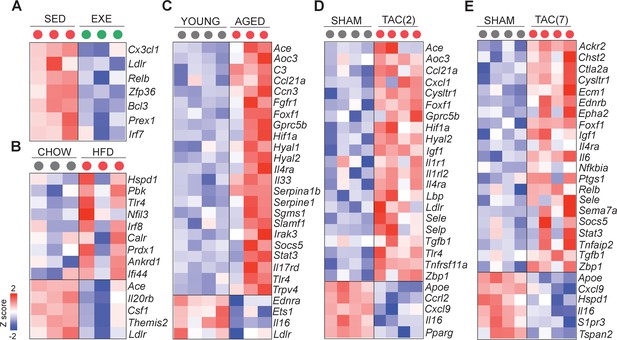

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors induce inflammatory gene expression in cardiac endothelial cells (ECs).

(A–E) Expression of inflammatory genes in the cardiac ECs of the indicated experimental groups. Genes were identified by comparing our data set with the Gene ontology term: Inflammatory response (GO:0006954) described in the http://www.informatics.jax.org/vocab/gene_ontology/GO:0006954. In panel (A–E), the up- and downregulated genes with false discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value) threshold of 0.05 were considered. In the heatmap, each color-coded circle (red, green, and black) indicates the gene expression data obtained from individual biological sample per experimental group. N = 3–4 male mice per group were analyzed.

-

Figure 3—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Source data for Figure 3—figure supplement 1A, B, C, D and E.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig3-figsupp1-data1-v2.xlsx

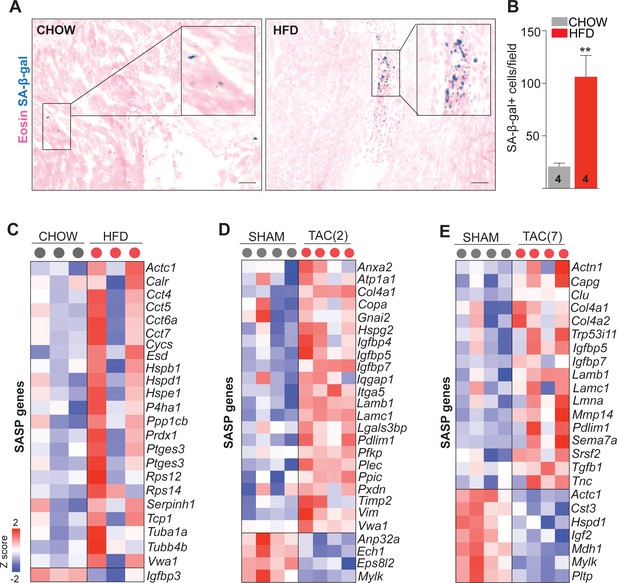

Obesity and pressure overload induce SASP gene expression and senescence in the heart.

(A and B) Representative images and quantification of the SA-β-galactosidase staining (in blue) detected at pH 6.0 in the high-fat diet and chow diet fed mouse hearts. (C–E) Expression of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) genes in the cardiac endothelial cells (ECs) of the indicated experimental groups. Genes were identified by comparing our data set with the previously published data sets deposited in the following databases: SASP Atlas (http://www.saspatlas.com) and SenQuest (https://senequest.net), and the endothelial expression of the genes were verified using Tabula Muris. In panels C–E, the up- and downregulated genes with false discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value) threshold of 0.05 were considered. In the heatmap, each color-coded circle (red, green, and black) indicates the gene expression data obtained from individual biological sample per experimental group. N = 3–4 male mice per group were analyzed. In panels A and B (N = 3–4 male mice per group), Scale bar 100 μm. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

-

Figure 3—figure supplement 2—source data 1

Source data for Figure 3—figure supplement 2B, C, D and E.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig3-figsupp2-data1-v2.xlsx

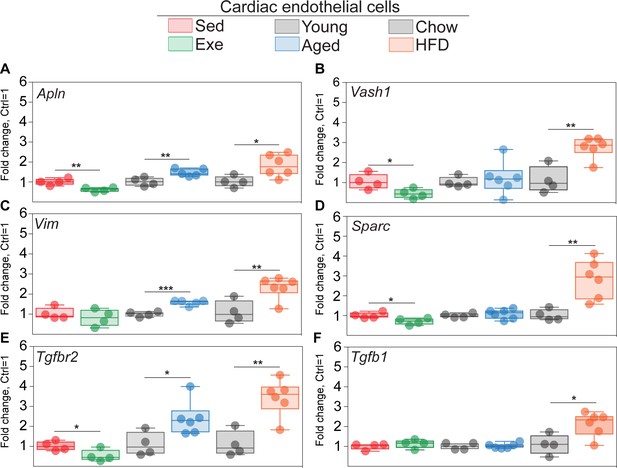

QPCR validation of selected genes in the cardiac endothelial cells (ECs) of aged, obese, and exercise trained mice.

(A–F) mRNA expression of Apln, Vim, Tgfbr2, Vash1, Sparc, and Tgfb1 in the cardiac EC of the indicated experimental groups (N = 4–6 male mice/group). Gene expression is normalized to Hprt1 expression. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

-

Figure 3—figure supplement 3—source data 1

Source data for Figure 3—figure supplement 3A, B, C, D, E and F.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig3-figsupp3-data1-v2.xlsx

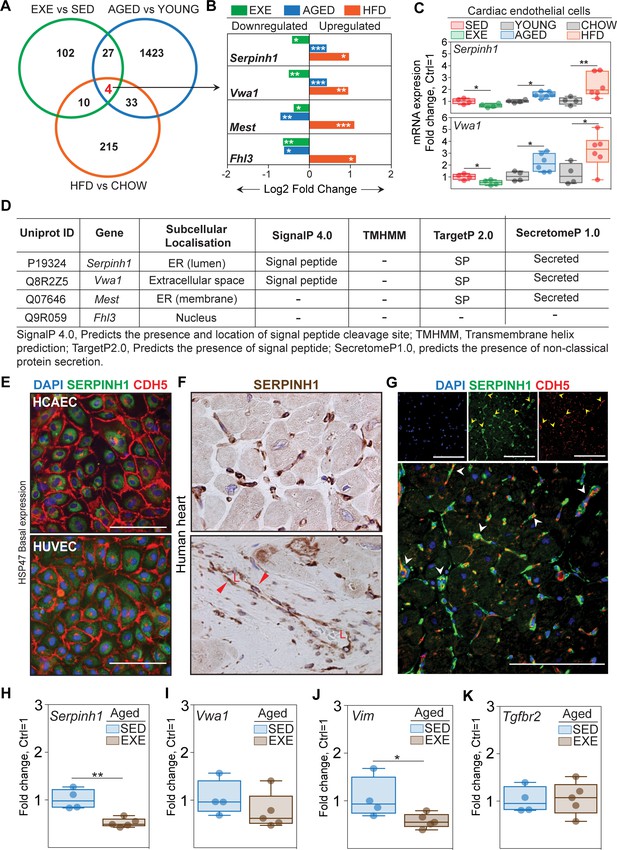

Serpinh1 expression is increased by aging and obesity and repressed by exercise training.

(A) A Venn diagram showing the overlap of differentially expressed genes between the experiments. Four genes were identified to be significantly affected by aging, obesity, and exercise (Serpinh1, Vwa1, Mest, and Fhl3). (B) Bar plot showing the expression pattern of these four genes. In panels (A and B), the up- and downregulated genes with the false discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value) threshold of 0.05 were considered to be significant (N = 3–4 male mice/group). (C) qPCR validation of Serpinh1 and Vwa1 normalized to Hprt1 (N = 4–6 male mice/group). (D) In silico secretome analysis of the identified genes. (E–G) Representative immunofluorescent and immunohistochemistry images showing the expression of SERPINH1 in human endothelial cell (EC) and human heart samples. Red arrowhead in the bottom panel F indicates the expression in large vessels and ‘L’ indicates vessel lumen. White arrowheads in the panel G denote the co-expression of SERPINH1 and CDH5 in coronary vessels (yellow signal). (H–K) mRNA expression of Serpinh1, Vwa1, Vim, and Tgfbr2 in the cardiac ECs of sedentary and exercise trained aged mice (N = 4–5 female mice/group). Scale bar 100 μm. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Source data for Figure 4B, C, H, I, J and F.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig4-data1-v2.xlsx

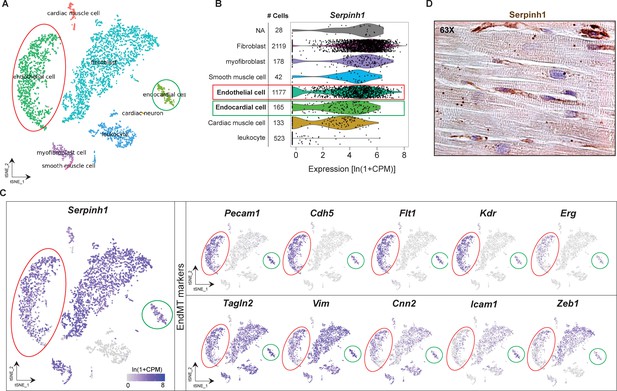

Expression of Serpinh1 in different cardiac cell types and in the human heart.

A tSNE plot showing (A) cardiac cell types in the adult mouse heart. (B) Violin plots showing the levels of SerpinH1 transcripts in fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells (ECs), endocardial cells, cardiac muscle cells, and leucocytes (each black dot denotes a single cell). (C) tSNE plot showing the expression of Serpinh1 and EndMT genes in the EC cluster (cells within the red circle) and endocardial cluster (cells within the green circle). Illustrations in the panels A–C were analyzed and acquired from a publicly available single-cell database Tabula muris: https://tabula-muris.ds.czbiohub.org/. (D) Representative longitudinal IHC image of human heart demonstrating strong SERPINH1 expression in interstitial cells (fibroblasts, ECs) and weak staining within cardiomyocytes. Scale bar 100 μm.

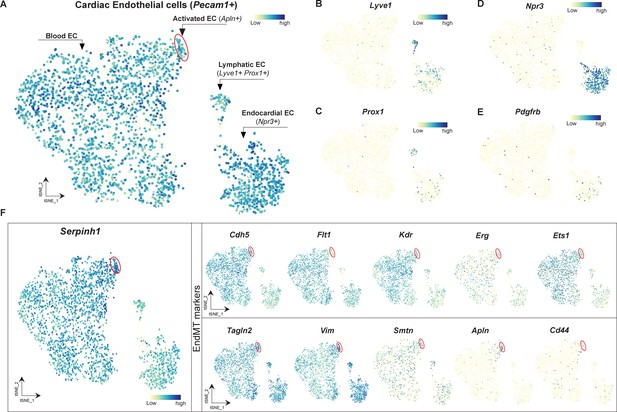

Serpinh1 expression in different subsets of cardiac endothelial cell (EC).

(A–D) A t-SNE plot showing the blood EC (activated EC (Apln+) highlighted within red circle), lymphatic EC (lyve1+ Prox1+), and endocardial EC (Npr3+). (E) Pdgfrb expression in cardiac EC population. (F) Serpinh1 is expressed in all EC populations, and especially highly expressed in Apln+ activated EC (cell cluster within red circle), which also has increased expression of mesenchymal genes (Tagln2, Vim, Smtn, and Cd44). Data in this figure were obtained and analyzed from publicly available EC atlas (https://endotheliomics.shinyapps.io/ec_atlas/).

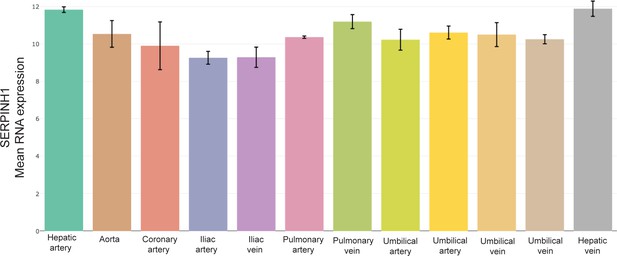

SERPINH1 RNA levels in the human arterial and venous endothelial cells.

RNA expression of SERPINH1 in human arterial and venous endothelial cells in the indicated organs organs. Data obtained by analysing the publicly available datasets (E-GEOD-43475 in the EndoDB database; https://endotheliomics.shinyapps.io/endodb/).

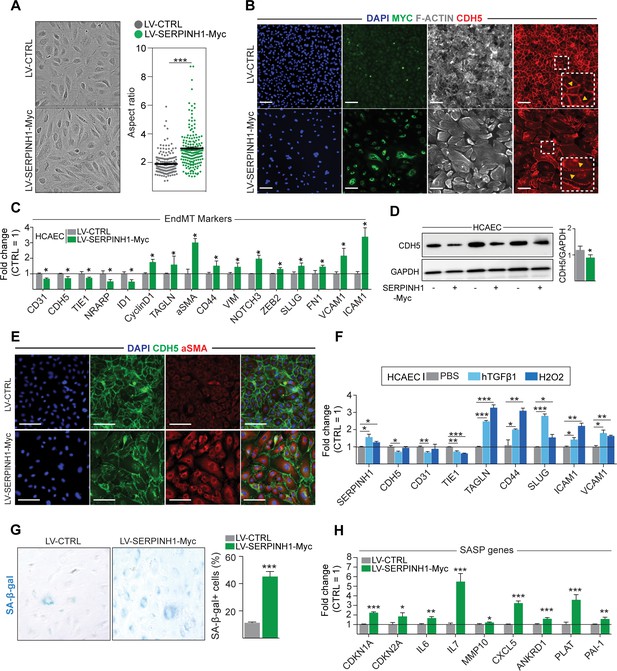

Overexpression of SERPINH1 modifies the endothelial cell (EC) phenotype and induces mesenchymal gene expression in human cardiac ECs.

(A) Representative phase-contrast images of live human cardiac arterial EC (HCAEC) transduced with LV-CTRL and LV-SERPINH1-Myc, and quantification of the aspect ratio (length to width ratio) of the cell. (B) Representative immunofluorescent images showing the expression of Myc-tagged SERPINH1 in green, F-Actin in gray, and CDH5/VE-Cadherin in red. The inset within the white box shows magnified view of VE-Cadherin junctions in HCAECs. (C) qPCR analysis of endothelial and mesenchymal markers in SERPINH1 overexpressing cells. (D) Western blot analysis and quantification of CDH5/VE-cadherin expression in the SERPINH1 overexpressing HCAECs (normalized to GAPDH). (E) Representative immunofluorescent images showing DAPI in blue, CDH5/VE-Cadherin in green, and α-smooth muscle actin (aSMA) in red. (F) qPCR analysis of SERPINH1 and EndMT markers in HCAECs stimulated with TGF-β1 (50 ng/ml) or H2O2 for 5 days. (G) Representative images and quantification of SA-β-gal+ senescent cells (in blue) normalized to total nuclei (%) in SERPINH1 overexpressing and control cells. (H) qPCR analysis of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) genes in HCAECs transduced with LV-CTRL and LV-SERPINH1-Myc. In panels A, C, D, F, G, and H, N = 3 biological replicates/group were analyzed. Scale bar 100 μm. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Source data for Figure 5A, C, D, F, G and H.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig5-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 5—source data 2

Source data for Figure 5D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig5-data2-v2.pptx

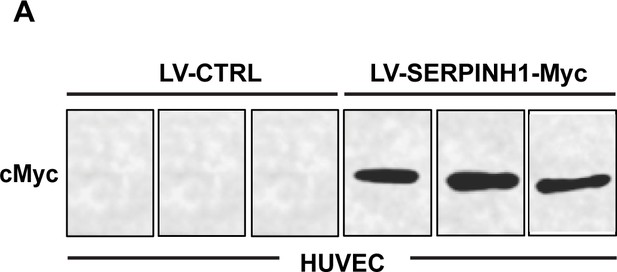

SERPINH1 overexpression in endothelial cells.

(A) Western blot analysis of cMyc expression in LV-SERPINH1-Myc-treated human umbilical venous EC (HUVEC; N = 3/group).

-

Figure 5—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Source data for Figure 5—figure supplement 1A.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig5-figsupp1-data1-v2.pptx

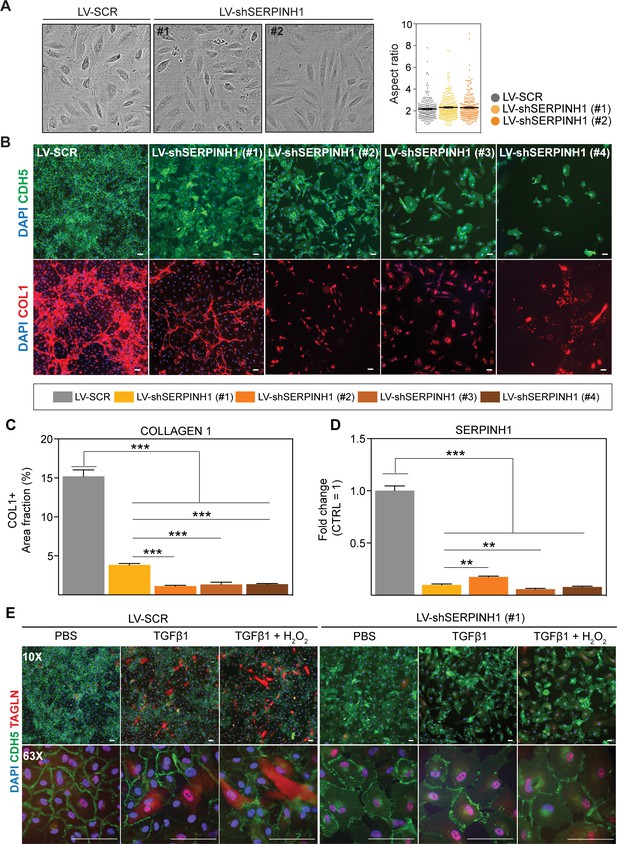

SERPINH1 silencing in human cardiac endothelial cell (EC) inhibits collagen production and EndMT.

(A) Representative phase contrast images of live human cardiac arterial ECs (HCAECs) transduced with LV-SCR and LV-shSERPINH1 (#1 and #2) and quantification of the aspect ratio (length to width ratio) of the cells 48 hr after transduction. (B) Representative CDH5/VE-Cadherin immunofluorescent images (green) showing the cell morphology and density after 10 days of SERPINH1 silencing. Collagen 1 staining is shown in red, and quantification of collagen 1 is shown in C. (D) qPCR analysis of SERPINH1 deletion levels using four independent constructs. (E) Representative immunofluorescent images showing TAGLN expression in the control and SERPINH1 silenced HCAECs treated with recombinant human TGF-β1 with and without H2O2 for 5 days. In the panels (A, C and D), N = 3 biological replicates/group were analyzed. Scale bar 100 μm. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Source data for Figure 6A, C and D.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig6-data1-v2.xlsx

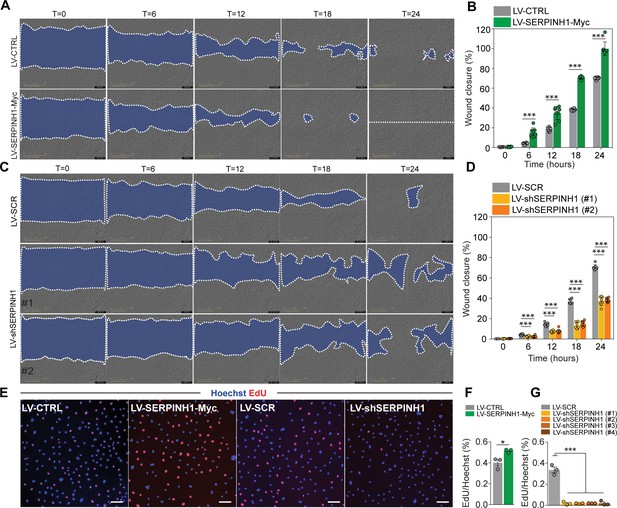

SERPINH1 overexpression enhances and silencing inhibits wound closure in vitro.

(A and B) Representative phase contrast images of scratch wound healing assay performed in human cardiac arterial ECs (HCAECs) treated with LV-CTRL and LV-SERPINH1, and quantification of the wound closure (%) with respect to time (hours). (C and D) Representative phase contrast images of scratch wound healing assay performed in HCAECs treated with LV-SCR and LV-shSERPINH1 (#1 and #2), and quantification of the wound closure (%) with respect to time (hours). (E–G) Representative immunofluorescent images of EdU incorporation in HCAECs treated with LV-Ctrl, LV-SERPINH1-Myc, LV-Scr, and LV-shSERPINH1 (#1, #2, #3, and #4), and quantification of EdU+ nuclei (red) normalized to Hoechst+ nuclei (blue). In the panels (A and C), the blue area within the white dotted region indicates the wound area. In the panels (B and D), N = 8 biological replicates/group and in (F and G), N = 3 biological replicates/group were analyzed. Scale bar 100 μm. Data is presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test was used, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

Source data for Figure 7B, D, F and G.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/62678/elife-62678-fig7-data1-v2.xlsx

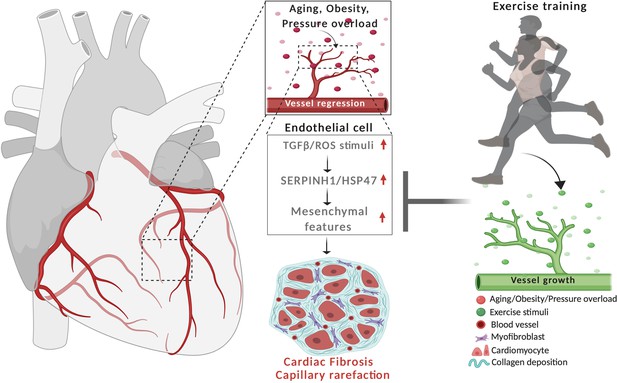

Schematic demonstrating the cardiovascular disease risk factor mediated activation of TGF-β signaling and acquisition of mesenchymal gene features in cardiac EC.

CVD risk factors aging, obesity and pressure overload trigger the regression of coronary vasculature by activating TGF-β/ROS signaling pathways and cellular senescence. These induce the expression of SerpinH1/HSP47 and mesenchymal gene signature. SerpinH1/HSP47 and EndMT are both involved in the development of tissue fibrosis by increasing collagen deposition in the extracellular matrix. Exercise training, in turn, increases coronary vasculature density, EC number, and represses TGF-β signaling, mesenchymal gene expression, and cellular aging related pathways.

Tables

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic reagent (M. musculus) | C57BL/6J | Janvier Labs | RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 | |

| Cell line (Homo sapiens) | HCAEC, HUVEC | PromoCell | ||

| Transfected construct (Homo sapiens) | SERPINH1 (Homo sapiens), shRNA(#1) | TRC library database, Broad institute | TRCN0000003590 | Lentiviral construct to transfect and express the shRNA |

| Transfected construct (Homo sapiens) | SERPINH1 (Homo sapiens), shRNA(#2) | TRC library database, Broad institute | TRCN0000003594 | Lentiviral construct to transfect and express the shRNA |

| Transfected construct (Homo sapiens) | SERPINH1 (Homo sapiens), shRNA(#3) | TRC library database, Broad institute | TRCN0000003593 | Lentiviral construct to transfect and express the shRNA |

| Transfected construct (Homo sapiens) | SERPINH1 (Homo sapiens), shRNA(#4) | TRC library database, Broad institute | TRCN0000003591 | Lentiviral construct to transfect and express the shRNA |

| Transfected construct (Homo sapiens) | FUW-SERPIH1-Myc (Homo sapiens) | This paper | Lentiviral construct to transfect and express overexpress SERPINH1-Myc | |

| Biological sample (Homo sapiens) | Heart samples from donors | Helsinki University Hospital | ||

| Antibody | (Rat monoclonal), FITC-CD31 | Invitrogen | RM5201, RRID:AB_10373983 | FACS (1:100) |

| Antibody | (Rat monoclonal), Pacificblue-CD45 | Biolegend | 103125, RRID:AB_493536 | FACS (1:100) |

| Antibody | (Rat monoclonal), Pacificblue-Ter119 | Biolegend | 116231, RRID:AB_2149212 | FACS (1:100) |

| Antibody | (Rat monoclonal), PE-Cyanine7-CD140a | eBioscience | 25-1401, RRID:AB_2573399 | FACS (1:100) |

| Antibody | (Rat monoclonal), CD16/CD32 (Fc blocker) | BD Biosciences | 553142, RRID:AB_394657 | FACS (1:100) |

| Antibody | (Rat monoclonal), CD31 | BD Pharmingen | 553370, RRID:AB_394816 | Immunofluorescent (1:500) |

| Antibody | (Rabbit monoclonal), VEcadherin | Cell Signaling | 2500S, RRID:AB_10839118 | Immunofluorescent or western blotting (1:500) |

| Antibody | (Sheep Polyclonal), Tagln | R&D Biosystems | AF7886 | Immunofluorescent (1:500) |

| Antibody | (Mouse Monoclonal), c-MYC | Thermo Fisher | 13-2500, RRID:AB_2533008 | Immunofluorescent or western blotting (1:500) |

| Antibody | (Mouse Monoclonal), HSP47/SERPINH1 | Enzo Life Sciences | ADI-SPA-470-D, RRID:AB_2039239 | Immunofluorescent immunohistochemistry or western blotting (1:1000) |

| Antibody | (Rabbit Polyclonal), Collagen 1 | Abcam | ab34710, RRID:AB_731684 | Immunofluorescent (1:1000) |

| Antibody | (Mouse Monoclonal), aSMA | Sigma-Aldrich | A5228, RRID:AB_262054 | Immunofluorescent (1:500) |

| Antibody | (Mouse Monoclonal), GAPDH | Millipore | CB1001, RRID:AB_2107426 | Western blotting (1:500) |

| Sequence-based reagent | hSERPINH1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ATGAGAAATTCCACCACAAGATG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hSERPINH1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GATCTTCAGCTGCTCTTTGGTTA |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCD31_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CTGCTGACCCTTCTGCTCTGTTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCD31_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GGCAGGCTCTTCATGTCAACACT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCDH5_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CGTGAGCATCCAGGCAGTGGTAGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCDH5_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GAGCCGCCGCCGCAGGAAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hTIE1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ACCCGCTGTGAACAGGCCTGCAGAGA |

| Sequence-based reagent | hTIE1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CTTGGCACTGGCTTCCTCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCYCLIND1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GCGGAGGAGAACAAACAGAT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCYCLIND1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TGAGGCGGTAGTAGGACAGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hTAGLN_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CGGTTAGGCCAAGGCTCTAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hTAGLN_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CCAGCTCCTCGTCATACTTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | haSMA_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | AAGCACAGAGCAAAAGAGGAAT |

| Sequence-based reagent | haSMA_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ATGTCGTCCCAGTTGGTGAT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCD44_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TGGCACCCGCTATGTCGAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCD44_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GTAGCAGGGATTCTGTCTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hVIM_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CGAGGAGAGCAGGATTTCTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hVIM_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GGTATCAACCAGAGGGAGTGA |

| Sequence-based reagent | hNOTCH3_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ACCGATGTCAACGAGTGTCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hNOTCH3_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GTTGACACAGGGGCTACTCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hZEB2_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GAGGCGCAAACAAGCCAATC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hZEB2_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TCAGAACCTGTGTCCACTAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hSLUG_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ACTCCGAAGCCAAATGACAA |

| Sequence-based reagent | hSLUG_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CTCTCTCTGTGGGTGTGTGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hFN1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CCATAGCTGAGAAGTGTTTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hFN1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CAAGTACAATCTACCATCATCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hVCAM1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CGCAAACACTTTATGTCAATGTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hVCAM1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GATTTTCGGAGCAGGAAAGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hICAM1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TGCCCTGATGGGCAGTCAAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hICAM1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CCCGTTTCAGCTCCTTCTCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hHPRT1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TGAGGATTTGGAAAGGGTGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hHPRT1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TCCCCTGTTGACTGGTCATT |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCDKN1A_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CAGCATGACAGATTTCTACC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCDKN1A_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CAGGGTATGTACATGAGGAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCDKN2A_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | AGCATGGAGCCTTCG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCDKN2A_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ATCATGACCTGGATCGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hIL6_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GCAGAAAAAGGCAAAGAATC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hIL6_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CTACATTTGCCGAAGAGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hIL7_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TCGATCATTATTGGACAGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hIL7_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | AGGAAACACAAGTCATTCAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hMMP10_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ACCAATTTATTCCTCGTTGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hMMP10_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GTCCGTAGAGAGACTGAATG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCXCL5_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ATTTGTCTTGATCCAGAAGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hCXCL5_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TCAGTTTTCCTTGTTTCCAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hANKRD1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TGAGTATAAACGGACAGCTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hANKRD1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TATCACGGAATTCGATCTGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hPLAT_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GGAATTCCATGATCCTGATAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hPLAT_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TCCGGCAGTAATTATGTTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | hPAI-1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CGCAACGTGGTTTTCTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hPAI-1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CATGCCCTTGTCATCAATC |

| Sequence-based reagent | hNRARP | This paper | Taqman PCR probes | Hs01104102_S1 |

| Sequence-based reagent | mCdh5 | This paper | Taqman PCR probes | Mm00486938_m1 |

| Sequence-based reagent | mTie1 | This paper | Taqman PCR probes | Mm00441786_m1 |

| Sequence-based reagent | mSerpinH1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ATGTTCTTTAAGCCACACTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | mSerpinH1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TCGTCATAGTAGTTGTACAGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | mVwa1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GATGATCTTCCTATCATTGCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | mVwa1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CAATTCCAGCACGTAGTAAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | mVim_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CTTGAACGGAAAGTGGAATCCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | mVim_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GTCAGGCTTGGAAACGTCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | mTgfbr2_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | TCTTTTCGGAAGAATACACC |

| Sequence-based reagent | mTgfbr2_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GTAGCAGTAGAAGATGATGATG |

| Sequence-based reagent | mVash1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CAAGGAAATGACCAAAGAGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | mVash1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | ACTGTTGGTGAGGTAAATTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | mSparc_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GAACCCACATGGCAAGTCTTA |

| Sequence-based reagent | mSparc_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | AAAGCCCAATTGCAGTTGAGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | mTgfb1_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CTCCCGTGGCTTCTAGTGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | mTgfb1_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | GCCTTAGTTTGGACAGGATCTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | mApln_F | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CAGGCCTATTCCCAGGCTCA |

| Sequence-based reagent | mApln_R | This paper | SYBR green PCR primers | CAAGATCAAGGGCGCAGTCA |

| Peptide, recombinant protein | Recominant human TGF- β | R&D Technologies | 240-B | 50 ng/ml |

| Commercial assay or kit | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit | Applied biosystems | #4368814 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | FastStart Universal SYBR green master mix | Sigma-Aldrich | #04913914001 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | TaqMan gene expression master mix | Applied Biosystems | #4369016 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit V2 – Pico Input Mammalian | Takara Bio, USA | ||

| Commercial assay or kit | SA-β-gal staining kit | Cell signaling technology | #9860 | |

| Commercial assay or kit | Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 594 staining kit | Thermo scientific | C10339 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Hydrogen peroxide | Acros organics | AC202465000 | 200 μM |

| Software, algorithm | Chipster analysis platform (v3.12.2) | CSC, Finland | https://chipster.csc.fi | |

| Software, algorithm | Trimmomatic tool | Chipster, CSC, Finland | https://chipster.csc.fi/manual/trimmomatic.html | |

| Software, algorithm | HISAT2 package | Chipster, CSC, Finland | https://chipster.csc.fi/manual/hisat2.html | |

| Software, algorithm | HTSeq count tool | Chipster, CSC, Finland | https://chipster.csc.fi/manual/htseq-count.html | |

| Software, algorithm | DESeq2 Bioconductor package | Chipster, CSC, Finland | https://chipster.csc.fi/manual/deseq2-pca-heatmap.html | |

| Software, algorithm | PANTHER classification system (V.14.1) | http://www.pantherdb.org | ||

| Software, algorithm | VENNY 2.1 Venn-diagram analysis | BioinfoGP | https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/ | |

| Software, algorithm | MetazSecKB knowledgebase | http://proteomics.ysu.edu/secretomes/animal/index.php | ||

| Software, algorithm | TargetP2.0 server | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/index.php | ||

| Software, algorithm | SecretomeP1.0 server | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SecretomeP-1.0/ | ||

| Software, algorithm | Image J software | NIH, Bethesda | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html | |

| Software, algorithm | SASP atlas | http://www.saspatlas.com | ||

| Software, algorithm | SeneQuest | https://senequest.net | ||

| Software, algorithm | Tabula Muris | https://tabula-muris.ds.czbiohub.org | ||

| Software, algorithm | EndoDB | https://endotheliomics.shinyapps.io/endodb/ | ||

| Software, algorithm | Endothelial cell atlas | https://endotheliomics.shinyapps.io/ec_atlas/ |