Context-dependent relationships between locus coeruleus firing patterns and coordinated neural activity in the anterior cingulate cortex

Figures

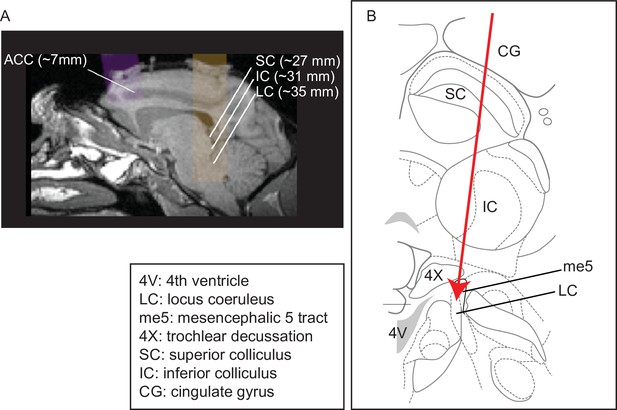

Recording site locations.

(A) Approximately sagittal MRI section showing targeted recording locations in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (areas 32, 24b, and 24c) and locus coeruleus (LC) for monkey Ci (right), with the SC and IC shown for reference. For recording locations in monkeys, Oz, Sp, and Ci (left hemisphere), see Kalwani et al., 2014; Joshi et al., 2016. (B) Schematic of a coronal section showing structures typically encountered along electrode tracts to LC (adapted from Paxinos et al., 2008; Plate 90, Interaural 0.3; bregma 21.60).

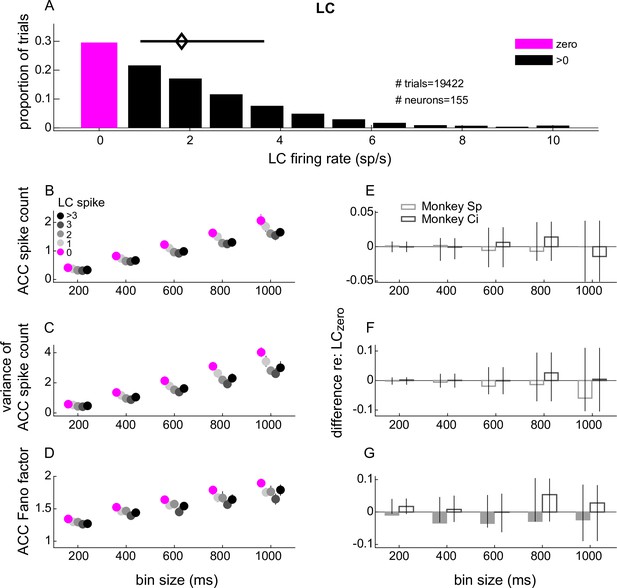

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) single-unit spike-count statistics conditioned on simultaneously measured locus coeruleus (LC) spiking.

(A) LC single-unit firing rate distribution measured in 1.1 s windows starting 1 s after the onset of stable fixation from all trials and recording sessions. The magenta and black bars indicate the proportion of trials with 0 and >0 LC spikes, respectively. The diamond and horizontal bar indicate median and interquartile range (IQR), respectively, from trials with ≥1 spike. (B–D) ACC single-unit spike count (B), variance of the spike count (C), and Fano factor (variance/mean; D) from trials in which the simultaneously measured LC unit spiked as indicated in the legend in (B). ACC spikes were counted in five equally spaced bins ranging from 200 ms to 1 s. Symbols and error bars are the median and bootstrapped 95% confidence interval of the distribution of values computed per ACC unit, pooling the data across all units recorded from both monkeys. (E–G) Difference between each value from panels (A–C), respectively, measured between the LC > 0 condition and the LC = 0 condition. Bars and error bars are the median and bootstrapped 95% confidence interval of the distribution of values computed per ACC unit. Filled bars and symbols above indicate p < 0.05 for sign-rank tests for H0: median difference between LCzero and LCnon-zero conditions = 0 tested: (1) separately for each monkey (filled bars) and (2) using data combined from both monkeys (*none found).

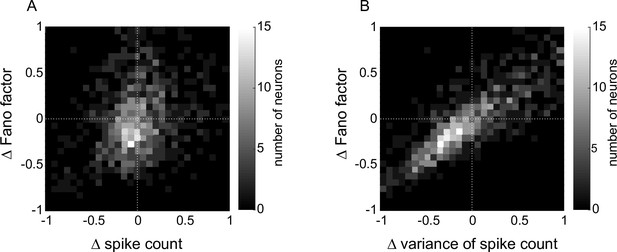

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) single-neuron spike count and variability conditioned on locus coeruleus (LC) spiking (measured as differences between measurements from LCnon-zero versus LCzero trials).

(A) Relationship between difference in Fano factor and difference in spike count; Spearman’s rho = 0.27, p = 2.6 × 10-17. (B) Relationship between difference in Fano factor and difference in variance of spike count; Spearman’s rho = 0.85, p < 0.00001.

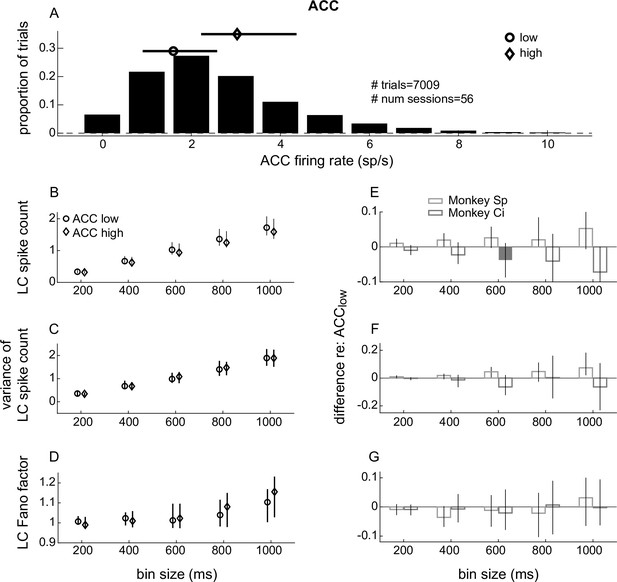

Locus coeruleus (LC) single-unit spike-count statistics conditioned on simultaneously measured anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) spiking.

(A) ACC single-unit firing rate distribution measured in 1.1 s windows starting 1 s after the onset of stable fixation from all trials and recording sessions. The circle and diamond symbols and lines indicate the median and interquartile range (IQR) of trials defined as ‘low’ and ‘high’ ACC spike counts (median split per session), respectively. (B–D) LC single-unit (B) spike count, (C) variance of spike count, and (D) Fano factor (variance/mean) from trials in which the simultaneously measured ACC activity (mean firing rate of all single units) was low or high as indicated by the markers defined in (B). LC spikes were counted in five equally spaced bins ranging from 200 ms to 1 s. Symbols and error bars are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the values computed by pooling the data across all units recorded from both monkeys. (E–G) Difference between each value from panels (B–D), respectively, measured between the ACChigh condition and the ACClow condition. Bars and error bars are the median and bootstrapped 95% confidence interval of the distribution of values computed per LC unit. Filled bars and symbols above indicate p < 0.05 for sign-rank tests for: (1) H0: median difference between ACClow and ACChigh conditions tested separately for each monkey = 0 (filled bars) and (2) H0: median difference between ACClow and ACChigh conditions tested using data combined from both monkeys = 0 (*none found).

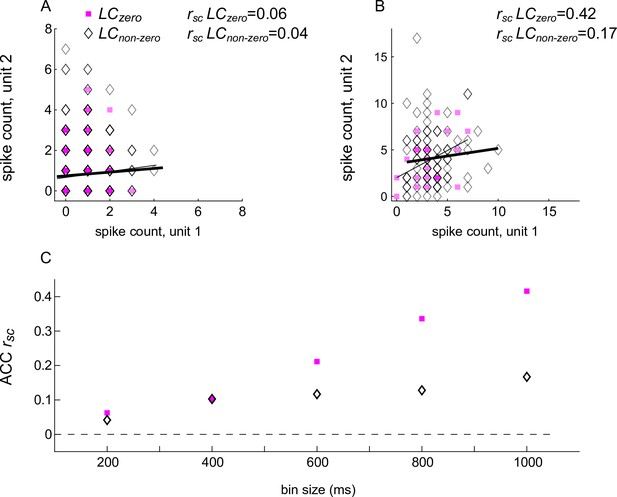

Spike-count correlations (rsc) of an example anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) pair conditioned on the spiking activity of a simultaneously recorded locus coeruleus (LC) unit.

(A) ACC spikes counted in a 200 ms-wide bin. (B) ACC spikes counted in a 1000 ms-wide bin. In (A) and (B), square/diamond markers indicate data from trials in which the simultaneously recorded LC unit had zero/non-zero firing rates. Thin/thick lines are linear fits to these data points, respectively. (C) Spike-count correlation (rsc) for the example ACC pair shown in (A) and (B) as a function of bin size, computed separately for trials in which the simultaneously recorded LC unit had zero/non-zero firing rates, as indicated in (A).

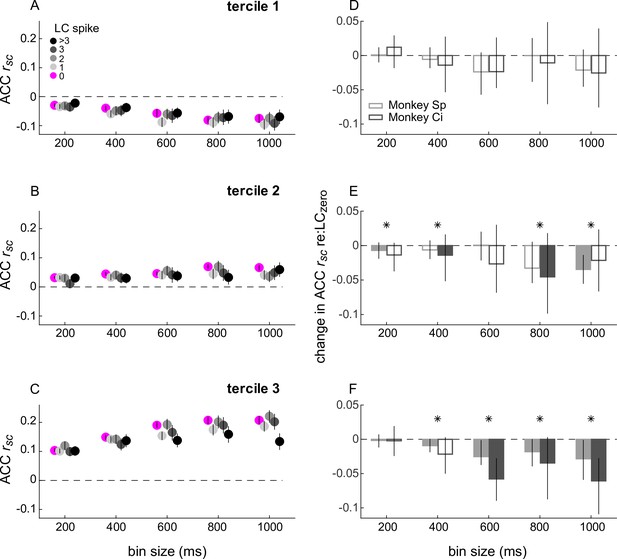

Spike-count correlations (rsc) within anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) conditioned on simultaneously measured locus coeruleus (LC) spiking.

(A–C) ACC rsc plotted as a function of bin size for each LC spike condition indicated in the legend in (A). The three panels separate data by ACC pairs with rsc values that, without reference to LC firing and for each bin size, were in the lower (A), middle (B), or upper (C) tercile from all recorded ACC pairs. Symbols and error bars are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals across the given set of ACC pairs. (D–F) Difference in ACC rsc between the LCnon-zero condition and the LCzero condition, computed for each ACC pair and plotted separately for the terciles in (A–C), respectively. Bars and error bars are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals across the given set of ACC pairs. Filled bars and symbols indicate p < 0.05 for sign-rank tests for H0: median difference between LCzero and LCnon-zero conditions = 0 tested: (1) separately for each monkey (filled bars) and (2) using data combined from both monkeys (*).

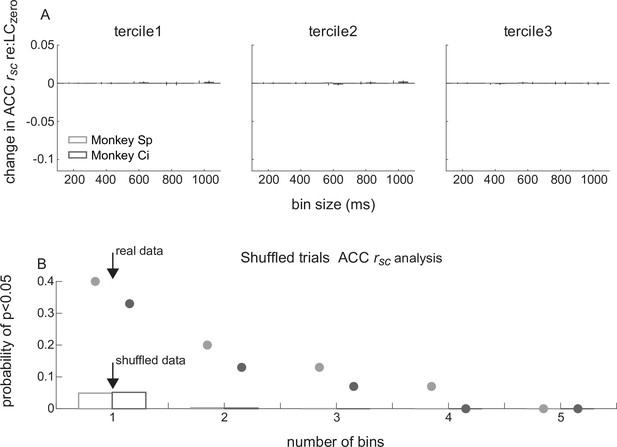

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) rsc conditioned on simultaneously measured locus coeruleus (LC) spiking using shuffled trials.

(A) Shuffled ACC rsc data conditioned on LC spiking, separated into terciles (panels, as labeled) of LC-independent values, plotted as in Figure 4A–C. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals are plotted as vertical lines (same ordinate scaling as Figure 4; bars and lines too small for visibility in most cases). (B) Probability of obtaining a statistically reliable difference in ACCrsc on LCzero versus LCnon-zero trials (sign-rank test, p < 0.05) in the given number of adjacent time bins tested. The time bins are 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 ms, as in (A), tested separately for each of the three terciles. Bars are for shuffled data, markers above bars are for the real (i.e., unshuffled) data, calculated separately for each monkey (shading). Thus, the probability of 0.4 for monkey Sp (light symbol), bin size = 1, corresponds to the 6/15 single bins from Figure 4D–F for which we rejected the null hypothesis that the mean difference = 0. Note that the probability of finding effects in up to three adjacent time bins from the real data was substantially higher than would be expected by chance (i.e., as predicted from the shuffled data).

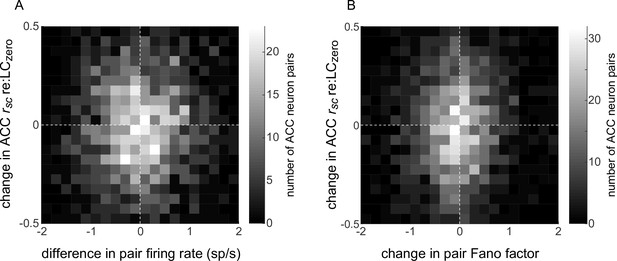

Relationship between locus coeruleus (LC)-linked changes in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) spiking and ACC rsc.

(A) For each simultaneously recorded pair of ACC units and single LC unit, the difference in ACC rsc computed from LCnon-zero versus LCzero trials (ordinate) is plotted versus the difference in the mean spike rate of the two ACC units computed from LCnon-zero versus LCzero trials (abscissa). Spearman’s rho = 0.02, p = 0.45. (B) Same as (A) but with the ACC pair Fano factor on the abscissa. Spearman’s rho = 0.05, p = 0.01.

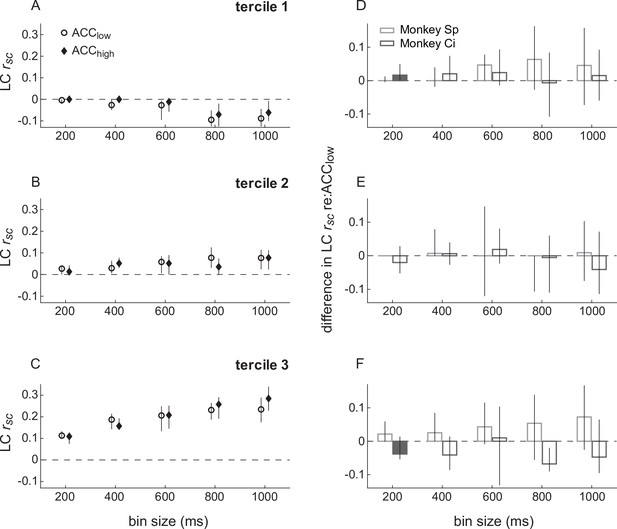

Spike-count correlations (rsc) within locus coeruleus (LC) conditioned on simultaneously measured anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) spiking.

(A–C) LC rsc plotted as a function of bin size separately for trials in which the simultaneously recorded ACC unit had a relatively low or high firing rate, as indicated in (A). The three panels separate data by LC pairs with rsc values that, without reference to ACC firing and for each bin size, were in the lower (A), middle (B), or upper (C) tercile from all recorded LC pairs. Symbols and error bars are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals across the given set of ACC pairs. (D–F) Difference in LC rsc between ACClow versus ACChigh conditions, relative to the ACC low condition, computed for each LC pair and plotted separately for the terciles in (A–C), respectively. Bars and error bars are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals across the given set of LC pairs. Filled bars and symbols indicate p < 0.05 for sign-rank tests for H0: median difference between ACClow and ACChigh conditions = 0 tested: (1) separately for each monkey (filled bars) and (2) using data combined from both monkeys (*none found).

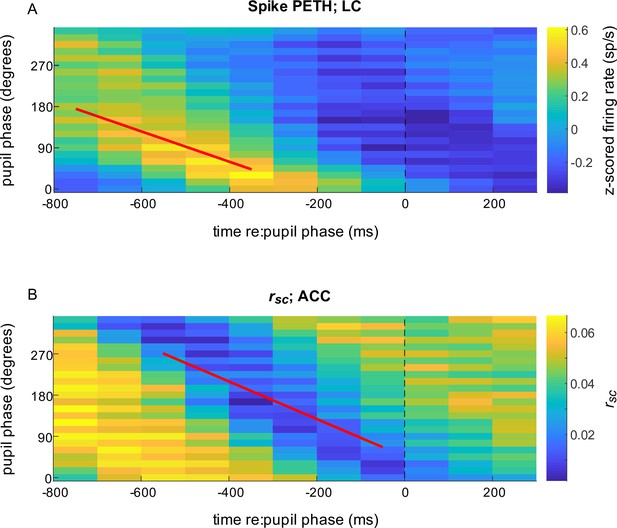

Spiking responses of locus coeruleus (LC) neurons and correlated activity in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) relative to pupil phase.

(A) Mean LC spike rate (colormap, in sp/s z-scored per unit) computed in 500 ms-wide bins aligned to the time of occurrence of each pupil phase. For each complete pupil cycle, phase is defined with respect to the maximum rate of dilation (0°), the maximum size (90°), the maximum rate of constriction (180°), and the minimum size (270°; see Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Thus, the color shown at time = t (abscissa), phase = p (ordinate) corresponds to the mean spiking rate from all LC neurons that occurred in a 500 ms-wide bin centered at t ms relative to the time of pupil phase p. Diagonal structure with a slope of ~–0.3 deg/ms implies a consistent relationship between LC firing and pupil phase for the given range of temporal offsets and pupil fluctuations, or hippus, that have a period of ~600 ms (Joshi et al., 2016). (B) ACC rsc aligned to pupil phase, computed as in (A). In both panels, data are combined from all sessions for visualization. Lines are plotted using the median regression coefficients from statistically reliable linear fits (H0: slope = 0, p < 0.05) to the maxima of phase-aligned LC spiking computed per unit (A; median [IQR] slope = −0.33 [–0.48–0.22] deg/ms) and minima of the phase-aligned ACC rsc computed per ACC pair (B; slope = −0.41 [–0.54–0.25] deg/ms).

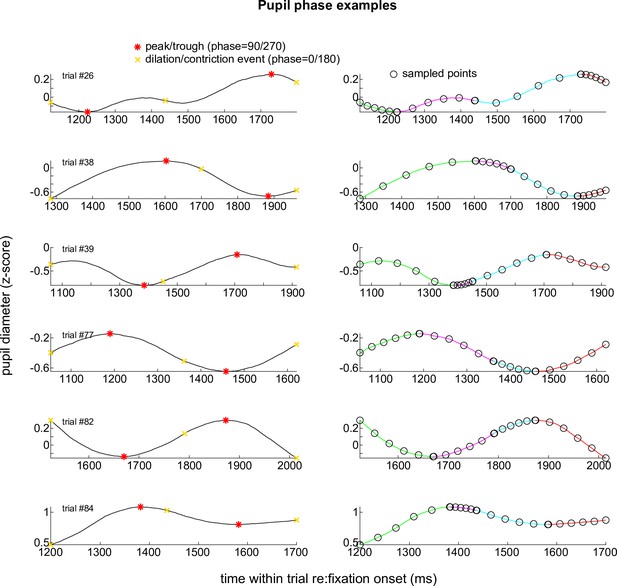

Pupil phase examples.

Example pupil traces from individual trials (rows) showing principal phases (left; 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°) and intermediate sampled points (right) used in the pupil analyses shown in Figure 6.

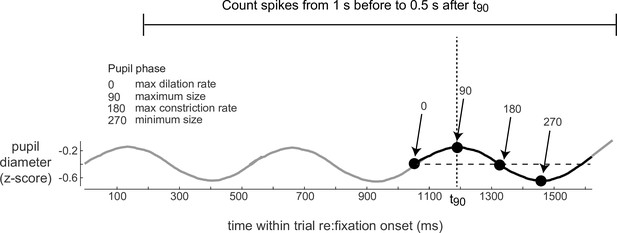

Measurement of spikes relative to pupil phase.

Schematic of a pupil trace from a single trial showing principal phases (left; 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°). One analyzed cycle is shown in bold with the time for phase = 90° indicated as t90. Locus coeruleus (LC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) spikes were counted in 500 ms bins in a 1.5 s window (indicated by the horizontal line above) and used to calculate the LC PETH and ACC rsc relative to this phase (and similarly for all phases between 0° and 360°, in 15° steps).

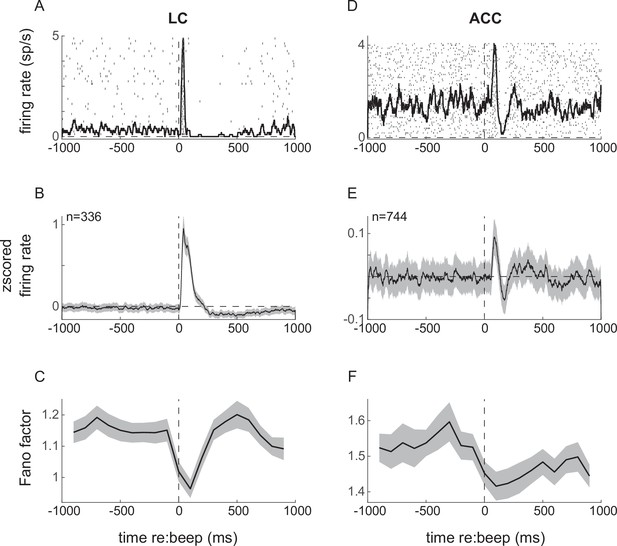

Neuronal responses to startling events (beep trials) in locus coeruleus (LC; left) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; right).

(A) Example LC unit spike raster and PSTH relative to beep onset. (B) LC population average response. (C) Fano factor as a function of time relative to beep onset, calculated in 200 ms windows. (D–F) ACC responses relative to beep onset plotted as in (A–C). Lines and ribbons in (B), (C), (E), and (F) indicate mean ± sem (standard error of the mean) across all trials for all monkeys.

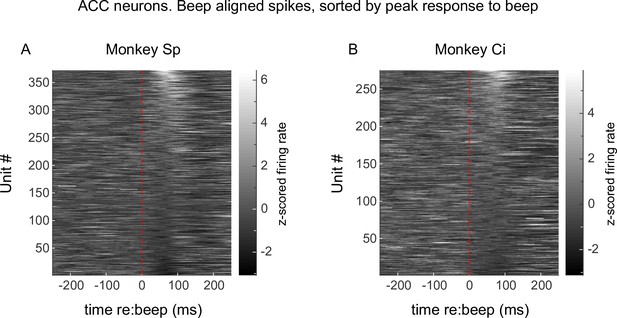

Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) single-unit responses to the startle stimulus (beep).

Average PSTHs aligned to beep onset from all units recorded from monkey Sp (A) and monkey Ci (B).

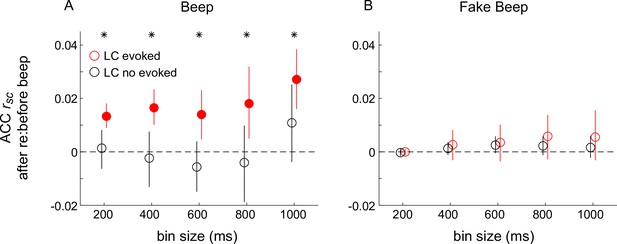

Differences in correlated activity in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in response to startling events, conditioned on locus coeruleus (LC) spiking.

(A) Beep-related difference in ACC rsc for trials in which LC had a transient response relative to trials in which LC had no transient response, plotted as a function of the bin size used to count spikes in ACC. Circles and vertical lines are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence estimates across the given set of ACC pairs. (B) Data from ‘fake-beep trials’ (trials with no beep but sorted according to whether or not there was a transient increase in LC spiking comparable in magnitude to the beep-evoked response), plotted as in (A). In both panels, asterisks indicate Mann–Whitney U-test for H0: median difference in ACC rsc (after relative to before the beep or ‘fake-beep’) between the two groups (LC-evoked and no-evoked) is different for the given time bin, p < 0.05 for both monkeys’ data pooled together; filled circles indicate sign-rank test for H0: ACC rsc differences (after relative to before the beep) within each group is different from zero, p < 0.05 for both monkeys’ data pooled together.

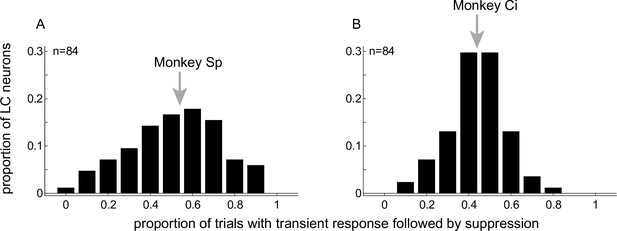

Consistency of locus coeruleus (LC) responses to startling sounds.

Histograms showing the proportion of LC neurons from monkeys Sp (A) and Ci (B) that exhibited a characteristic transient response followed by suppression for the given proportion of beep trials. Arrows indicate median values.

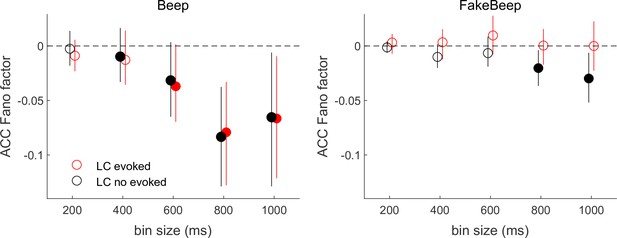

Differences in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) Fano factor in response to startling events, conditioned on locus coeruleus (LC) spiking.

(A) Beep-related difference in ACC Fano factor for trials in which LC had an evoked response relative to trials in which LC had no evoked response, plotted as a function of the bin size used to count spikes in ACC. Circles and vertical lines are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence estimates across the given set of ACC neurons. (B) Data from ‘fake-beep trials’ (trials with no beep but sorted according to whether or not there was a transient increase in LC spiking comparable in magnitude to the beep-evoked response), plotted as in (A). In both panels, Mann–Whitney U-test for H0: median difference in ACC Fano factor (after relative to before the beep or ‘fake-beep’) between the two groups (LC-evoked and not evoked) is different for the given time bin size, p < 0.05 for both monkeys’ data pooled together (*none found); filled circles indicate sign-rank test for H0: ACC Fano factor differences (after relative to before the beep) within each group is different from zero, p < 0.05 for both monkeys’ data pooled together.

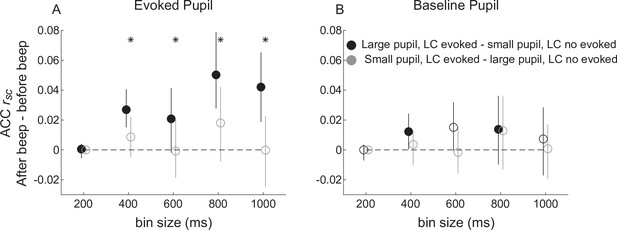

Beep-related differences in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) correlations relative to locus coeruleus (LC) responses and pupil size.

(A) Difference in ACC rsc computed after versus before the beep plotted as a function of bin size for trials groups based on evoked LC spiking and evoked pupil dilations (groups as indicated in the legend in B). (B) Difference in ACC rsc computed after versus before the beep plotted as a function of bin size for trials groups based on evoked LC and baseline pupil size. Circles and vertical lines are median and bootstrapped 95% confidence estimates across the given set of ACC pairs. In both panels, asterisks indicate Mann–Whitney U-test for H0: median difference in ACC rsc (after relative to before the beep) is different for trials with (LC-evoked) versus without (LC not evoked) a transient LC response for the given bin size, p < 0.05 for both monkeys’ data pooled together; filled circles indicate sign-rank test for H0: ACC rsc differences (after relative to before the beep) within each group is different from zero, p < 0.05 for both monkeys’ data pooled together. An ANOVA with groups (black and gray symbols as indicated in B), bin size, and pupil measure (baseline or evoked) as factors showed reliable effects of group and the interaction between group and pupil measure.

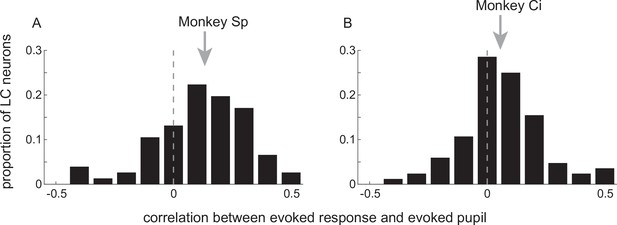

Relationship between startling sound-driven changes in pupil diameter and locus coeruleus (LC)-evoked activation.

Distribution of correlation coefficients describing unit-specific relationships between the size of the pupil response and the size of the evoked LC response to beep presentation for monkeys Sp (A) and Ci (B). Arrows indicate median values (sign-rank test for H0: median = 0, p < 0.001 in both cases).

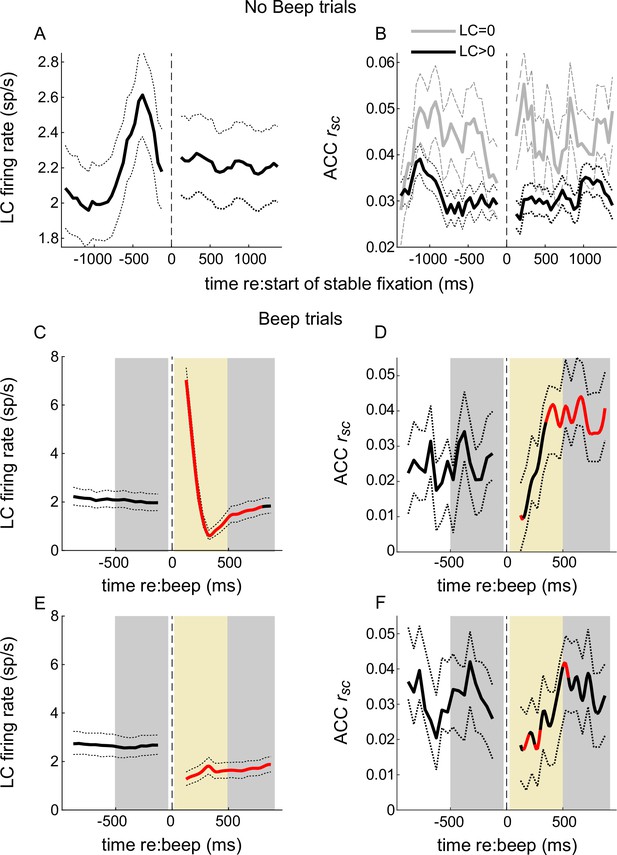

Temporal relationships between locus coeruleus (LC) firing and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) correlated activity.

No-beep trials: (A) LC firing rate aligned to the start of stable fixation. Solid and dotted lines are mean and bootstrapped 95% confidence estimates across the set of LC neurons. (B) Mean and 95% confidence estimates of ACC rsc computed across trials in time bins aligned to the start of stable fixation, separated into trials on which the simultaneously measured LC neuron did not (LC = 0) or did (LC > 0) fire an action potential. Beep trials (C–F). Panels as in (A) and (B), except with LC firing and ACC rsc now aligned to the time of the beep and separated into trials with (C, D) or without (E, F) an LC response to the beep. Red portions of lines indicate Mann–Whitney U-test for H0: per bin value is different from pre-beep baseline, p < 0.05 for both monkeys’ data pooled together. Gray shaded areas in (C–F) indicate epochs in which statistical comparisons were made for trials with (LC-evoked) versus without (LC not evoked) an LC transient response; gold shaded areas indicate epochs in which ACC rsc slopes were compared. For trials, see text.