Rolling controls sperm navigation in response to the dynamic rheological properties of the environment

Figures

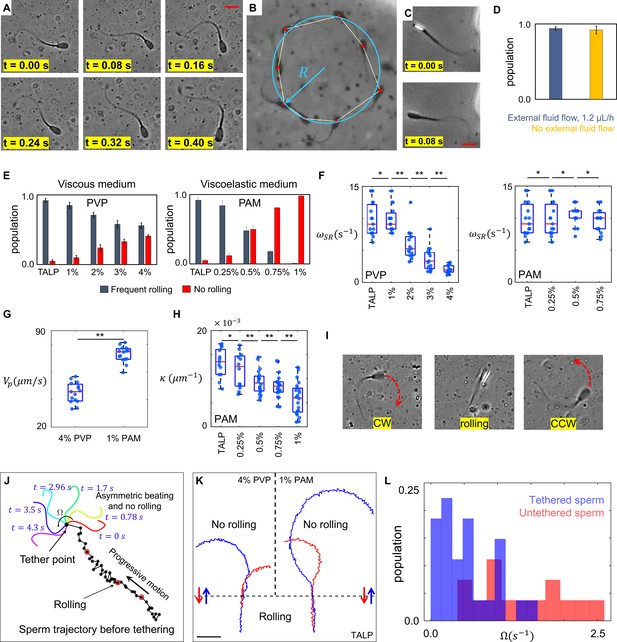

Sperm motility within the quiescent reservoir.

(A) Flagellar asymmetric beating. The midpiece of the flagellum consistently bends more prominently in one direction. (B) The circular motion caused by the asymmetric beating. A least-squares fitting algorithm was used to fit a circle into the sperm trajectory. (C) Rolling under a phase-contrast microscope. (D) All progressively motile sperm exhibit frequent rolling under flow and within the quiescent reservoir. (E) Increasing viscosity and viscoelasticity suppresses rolling and increases circular motion within the population (p>0.05). (F) An increase in viscosity results in a decrease in rolling frequency in rolling sperm while an increase in viscoelasticity does not change the frequency of rolling in rolling sperm. (G) Propulsive velocity of non-rolling sperm in 4% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) is significantly lower than that of 1% polyacrylamide (PAM). (H) Suppression of rolling for sperm exhibiting less asymmetry in their flagellation occurs at higher viscoelasticity. (I) Infrequent rolling changes the direction of motion from CW to CCW or vice versa. (J) Sperm rotating around the tethering point upon adhesion to the glass surface. Progressive motion before tethering was generated by frequent rolling. (K) Reversible transition between progressive and circular motions through suppression and reactivation of rolling. Trajectories in Tyrode’s albumin lactate pyruvate medium (TALP) and 1% PAM were obtained with 0.08 s intervals. Intervals in 4% PVP were 0.16 s. (L) Distribution of sperm angular velocity for both tethered and untethered sperm. **p>0.05, **p<0.01. The p-values were obtained from two-tailed t-tests, with adjustments for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction). The concentrations are reported in weight percent.

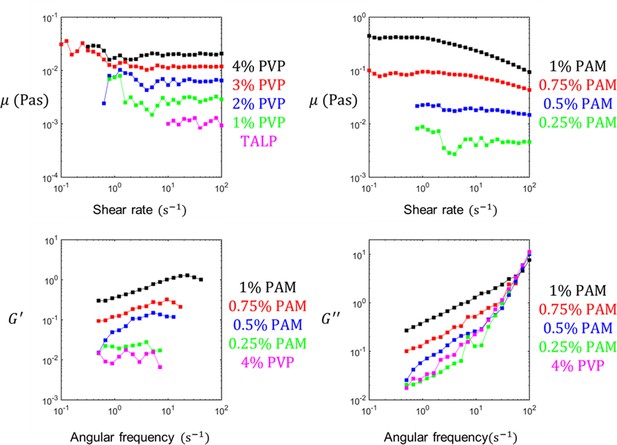

The rheological characteristics of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)- and polyacrylamide (PAM)-based sperm media.

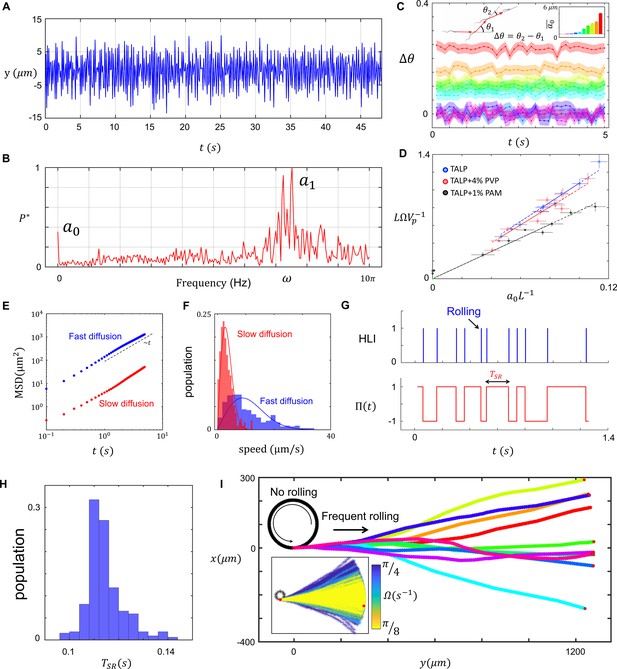

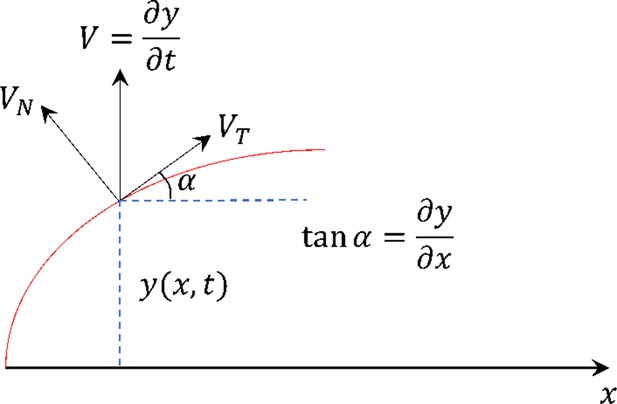

Characteristics of sperm motility.

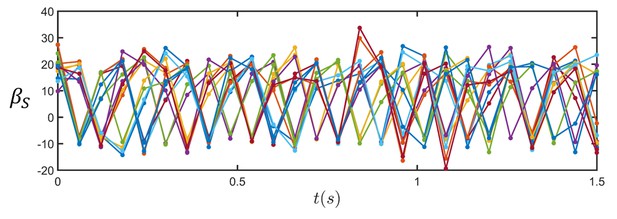

(A) Bending in the midpiece (). (B) The Fourier transform of , . (C) The average angle that the sperm sweeps in each beat, and the corresponding . (D) The normalized curvature of the path versus the normalized amplitude of the zeroth harmonic measured in Tyrode’s albumin lactate pyruvate medium (TALP), TALP + 4% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and TALP + 1% polyacrylamide (PAM). (E) Mean square displacement of the circular path’s center and (F) distribution of the center’s speed for two sperm swimming in circles. (G) The plot of head light intensity (HLI) versus time and the corresponding . (H) The distribution of for a single progressively swimming sperm with rolling. The distribution has mean and standard deviation of and , respectively. (I) A single sperm with arbitrary and frequent rollings swims progressively. The direction of progressive motion has a similar distribution to that of the frequent rolling, with mean and standard deviation of 0 and , respectively. See the effect of in the inset plot.

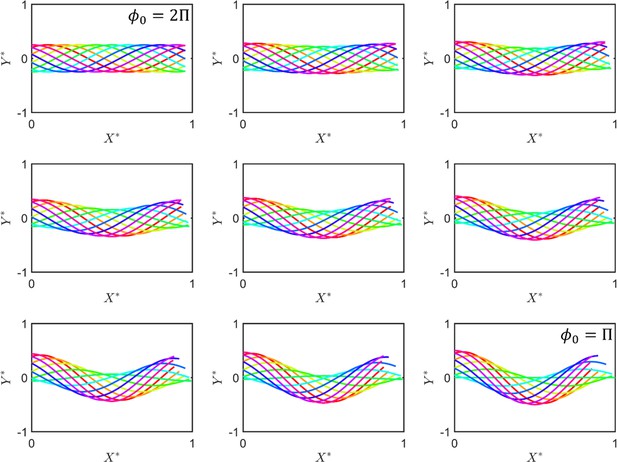

The beating pattern of the sperm flagellum.

The situation corresponds to symmetric beating, and thus to absolute progressive motility. As decreases, asymmetry in beating emerges and motility includes a circular motion ( and are normalized and axes as sperm motion can be described using the 2D Cartesian system).

The harmonics of sperm beating.

At , the beating pattern has a single 20 Hz frequency. As asymmetry emerges during beating, the main frequency shifts and higher harmonics along with the zeroth harmonic appear in the spectrum ( is the normalized amplitude of the harmonics).

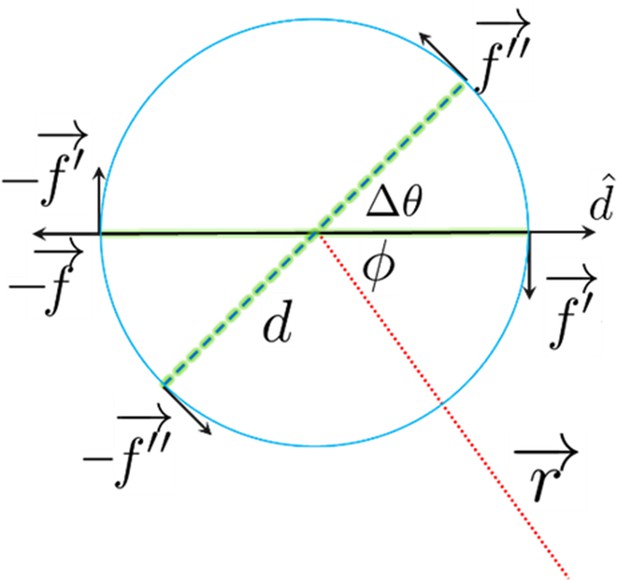

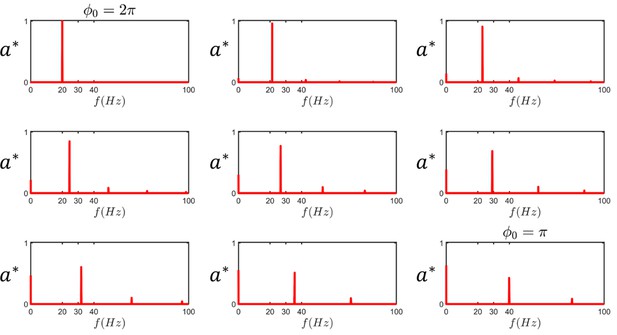

Schematic demonstrating the variables used in Equations S14–S17.

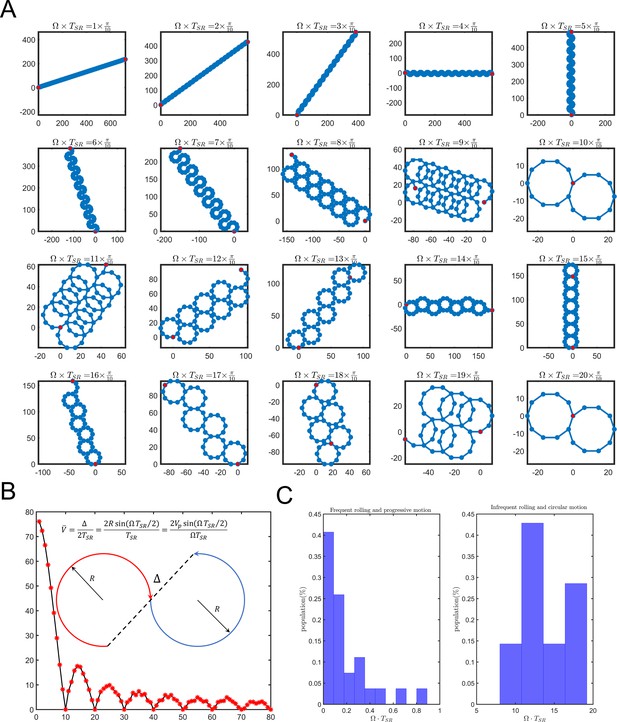

Dependence of sperm trajectory on .

(A) Sperm pathways for varying values of . At low values of , the sperm swims progressively, whereas at higher values the sperm swims in circles, subject to relocations. (B) Experimental measurements of for both progressive and circular motions. Data for circular motion without infrequent self-rolling are not presented. (C) Sperm velocity of the average path with respect to , showing that, when approaches 0, approaches .

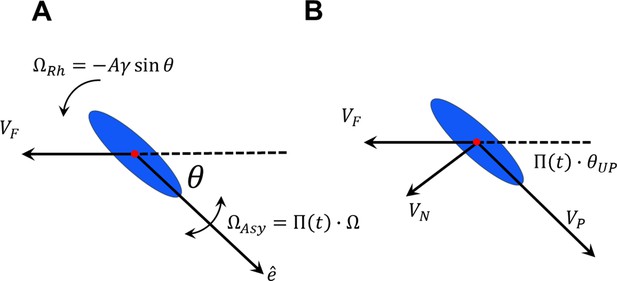

The influence of frequent rolling on sperm rheotaxis.

(A) Sperm orientation with respect to the fluid stream decreases with rolling. (B) Rolling alters the direction of the perpendicular velocity produced by asymmetrical beating and thus, increases the upstream component of motion.

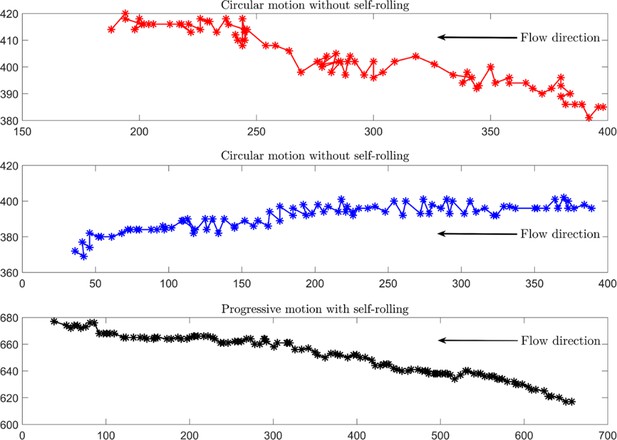

Experimental tracking of the sperm under an external fluid flow.

Unlike frequently rolling sperm, those without rolling exhibit inefficient upstream motion. x and y axes are in µm, and the time between two consecutive points is 0.08 s. External flow rate is 1.2 µL/h.

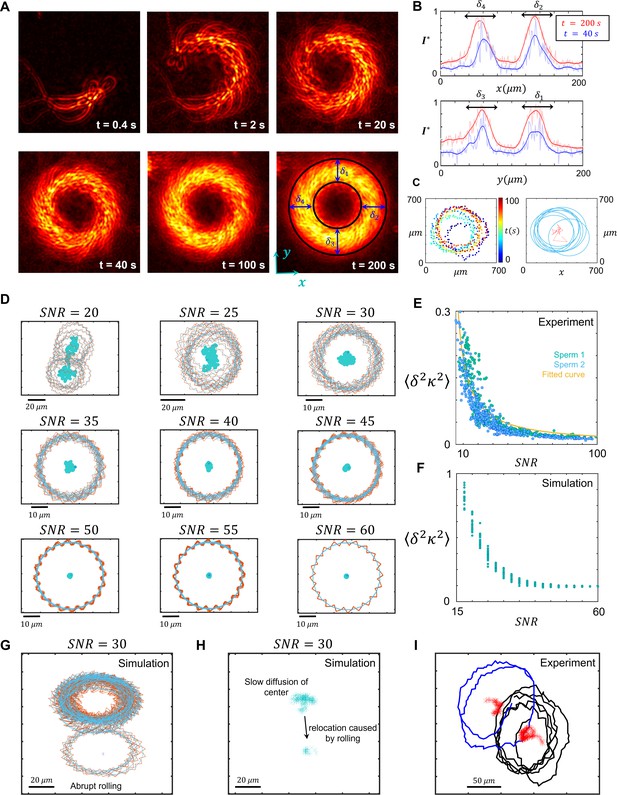

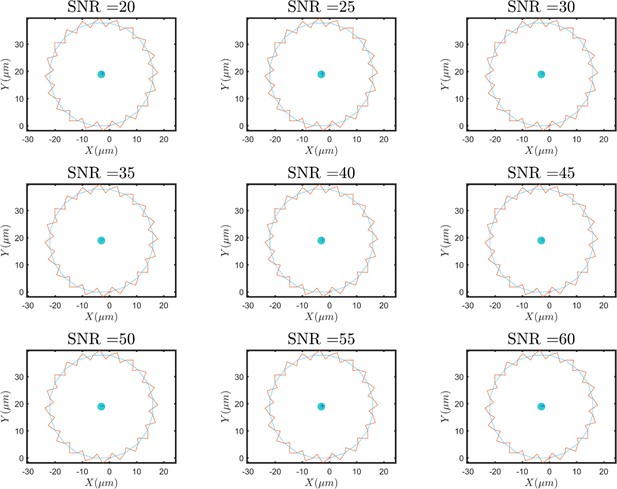

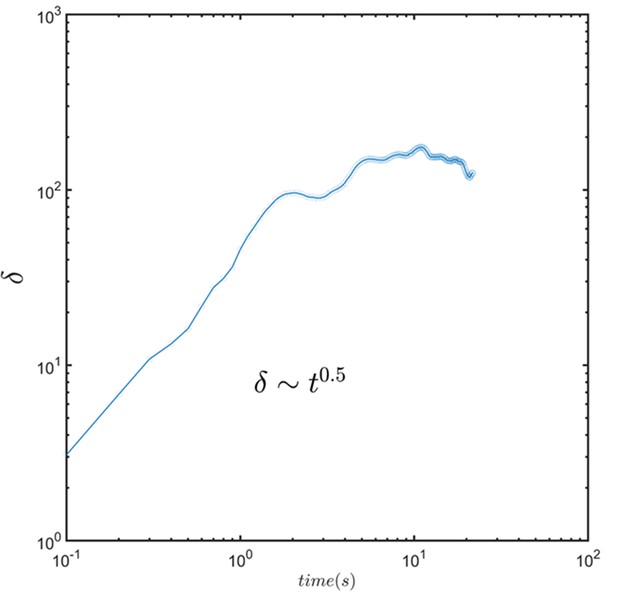

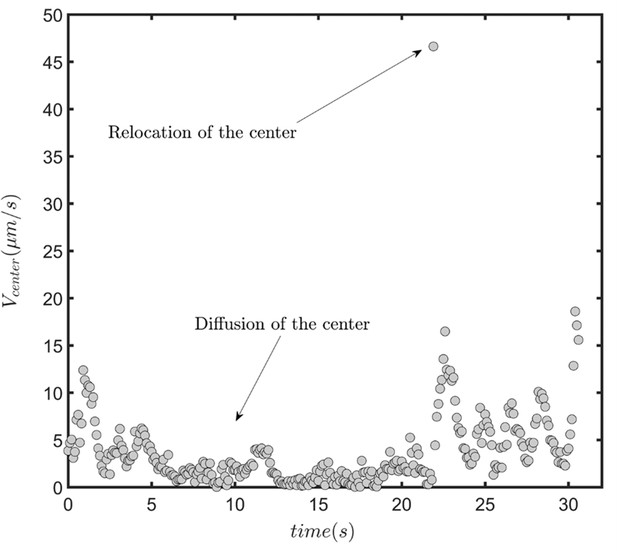

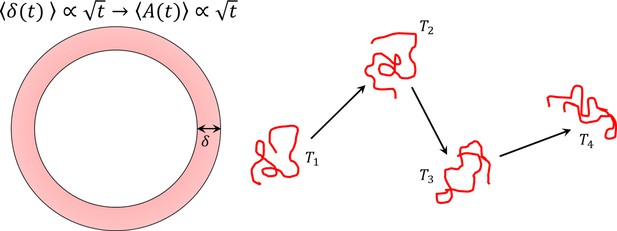

Infrequent rolling and diffusive circular motion.

(A) Overlayed consecutive images of a single sperm. Intervals: 0.08 s. (B) Diffusive motion increases in time. (C) Manual tracking of the sperm and the corresponding circular path’s center. (D) Trajectories of the sperm’s circular motion obtained by solving equations of motion. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) value is inversely correlated with the diffusion coefficient of the center. (E) Normalized mean step size obtained from experimental data and (F) from results shown in (D). (G) Infrequent rolling results in relocation of the center. (H) Two-phase intermittent search caused by infrequent rolling. (I) Experimental tracking of a sperm exhibiting intermittent search.

Noise in amplitude and frequency of the first and higher harmonics produces no diffusive motion in the circular path’s center.

The dynamic of thickness of the layer formed by combining the images of the sperm.

Average thickness increases with and can be modeled with a normal diffusion process.

The speed of the circular path’s center in the presence of infrequent rolling.

Infrequent rolling increases the area swept by circular motion and thus, the efficiency of surface exploration.

This two-phase motion is an intermittent search process.

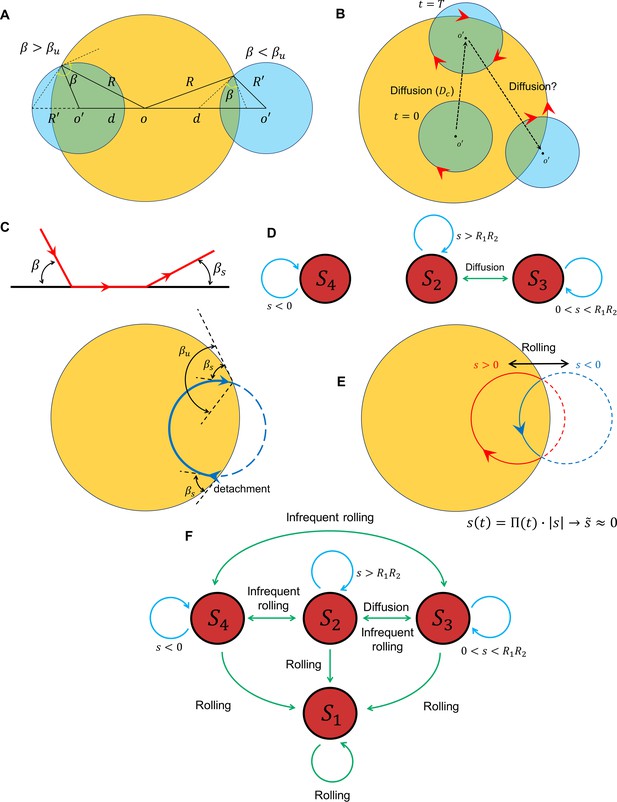

Sperm–wall interactions.

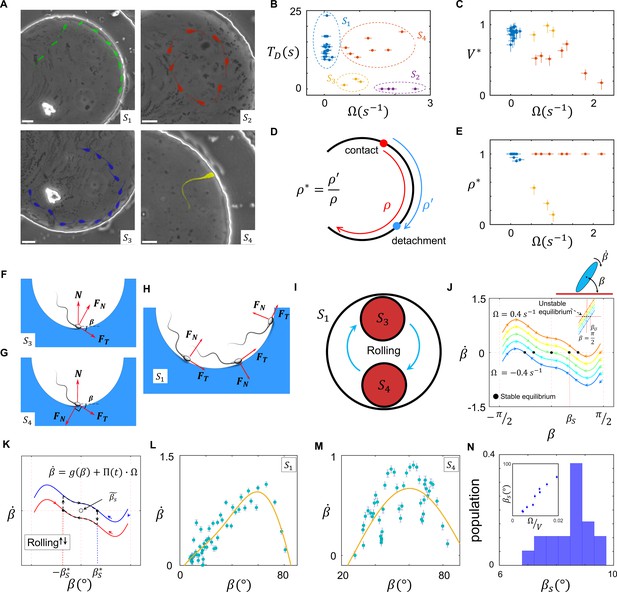

(A) Sperm–wall interaction categories. Rolling sperm rotate and align with the wall upon contact to swim stably along it . Non-rolling sperm exhibiting circular motion either do not contact the wall (), detach from the wall after temporarily swimming along it , or swim slowly along the wall depending on the magnitude and direction of angular velocity. (B) Sperm detention time on the wall, that is, . (C) Sperm normalized velocity on the wall, that is, . (D) A schematic to illustrate the definition of . (E) versus . (F) Free body diagram for the , (G) , and (H) categories. (I) Rolling results in alterations between and , forming . (J) The phase curves describing the dynamics of the angle between the sperm and wall after contact. Filled dots are stable points. Note that negative and positive values correspond to the and categories, respectively. (K) Rolling can be modeled as a transition between two-phase curves obtained for . A frequent transition between results in . (L) The phase curve for a rolling sperm. The final angle between the sperm and wall is ∼10°. (M) The phase curve for a non-rolling sperm. The final angle between the sperm and wall is ∼30°. (N) The distribution of for 20 rolling sperm. is linearly related to for non-rolling sperm (inset plot).

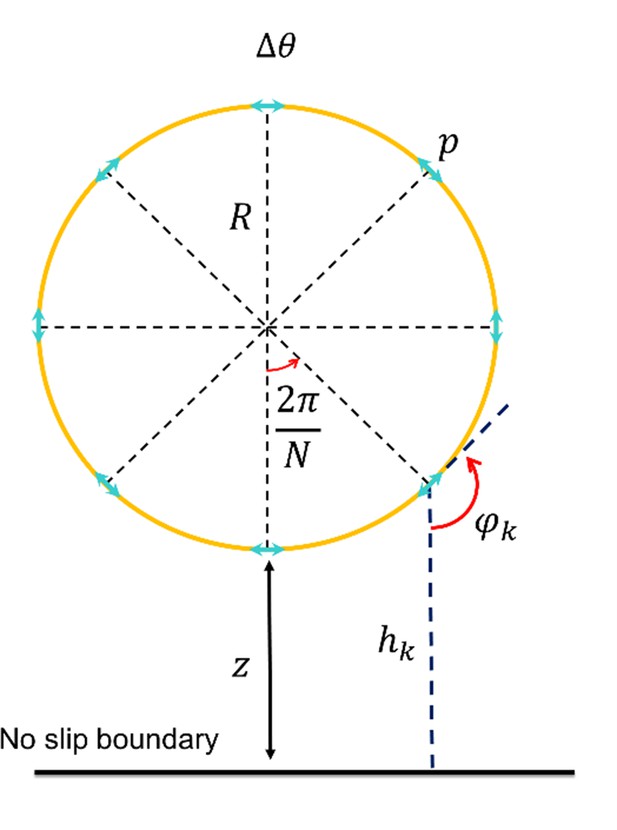

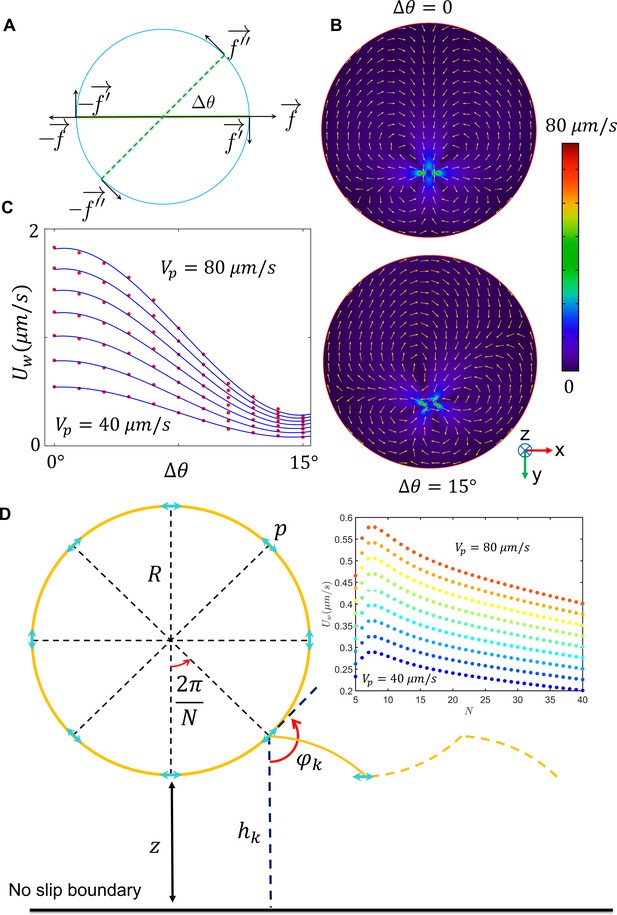

Far-field hydrodynamic interactions.

(A) Proposed swimmer model, including the terms corresponding to circular motion. (B) The velocity field imposed by active swimming of the swimmer at varying . (C) The drift velocity imposed by the wall for varying and . (D) The model acquired to calculate average drift velocity imposed on the sperm in one circulation. The average is less than 1 µm/s; thus, the far-field influence of the wall on sperm motion is much weaker than fluctuations in the circular path’s center.

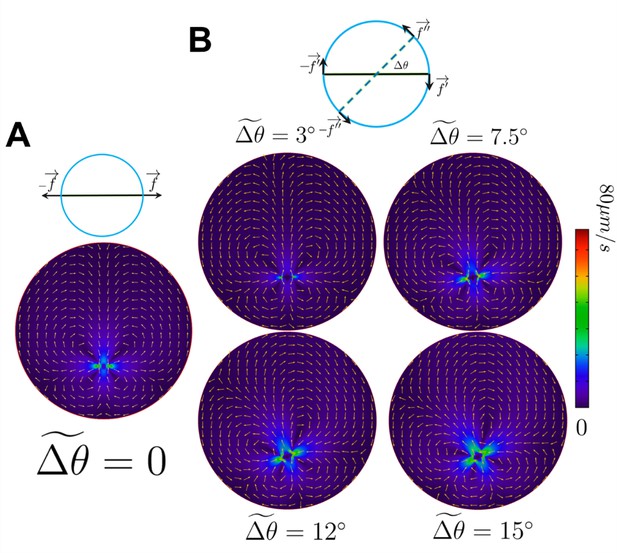

The flow field produced by the propulsive and circular components of motility.

(A) The flow produced by the propulsive component of motility and its corresponding drag. (B) The flow produced by the circular components of motility and their corresponding drags , ranging from 3° to 15°. The arrows are the normalized direction, whereas colors represent the magnitude of the velocity field.

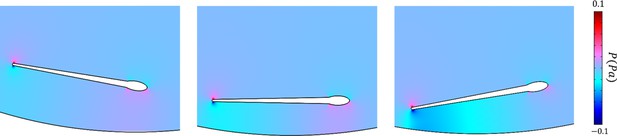

The distribution of pressure imposed by the wall on the sperm at near field.

The dynamics of sperm orientation with respect to the wall obeys a triangular function as predicted by the theory.

Transition between surface exploration and wall-dependent navigation.

(A) The circular path does not intersect with the reservoir for , whereas corresponds to and corresponds to . (B) Diffusivity in circular motion results in the evolution of , after which transforms into . (C) The angle at which the sperm detaches from the wall is independent of the incidence angle at the contact point. After the first contact and detachment, the sperm returns to the wall with . (D) State diagram of non-rolling sperm–wall interactions. (E) At the frequent rollings limit, the time average of approaches 0, where , which corresponds to . (F) Frequent rollings convert all the states into the state, whereas infrequent rollings result in reversible transitions between , and , as needed for an efficient surface exploration.