Social selectivity and social motivation in voles

Figures

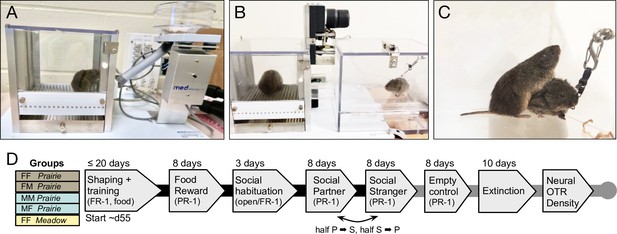

Overview of apparatuses, timeline, and testing groups.

(A) Lever pressing in voles was shaped and trained using food reinforcement. (B,C) In social operant testing a lever operated a motorized door, providing 1 min access to a conspecific tethered in a connected compartment. (D) Five groups were tested, abbreviated here as focal sex-partner sex-species abbreviation (e.g. FF Prairie indicates a female prairie vole trained as a lever presser and housed with a female partner). Prairie = prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster); Meadow = meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus). Black lines connect testing phases completed by all study subjects; gray lines connect additional phases completed by a subset of subjects.

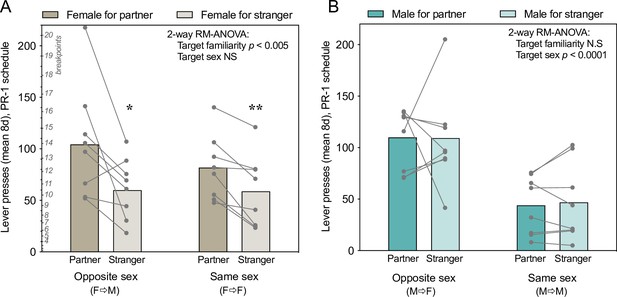

Sex-specific patterns of effort expended to access different social stimuli on a progressive ratio 1 (PR-1) schedule.

(A) Female prairie voles responded more for familiar than unfamiliar voles of either sex. (B) Male prairie voles pressing for females responded more than did males pressing for males, regardless of familiarity. Dots represent mean number of responses across eight 30 min PR-1 sessions for each vole. Bars represent group means. PR-1 breakpoint thresholds are listed in italics next to the corresponding number of responses on the interior y-axis of panel A and apply to all lever pressing data (e.g. a vole that presses 55 times should receive 10 rewards, the last of which takes 10 responses to gain). Asterisks indicate significant familiarity preferences within groups (paired t-tests). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

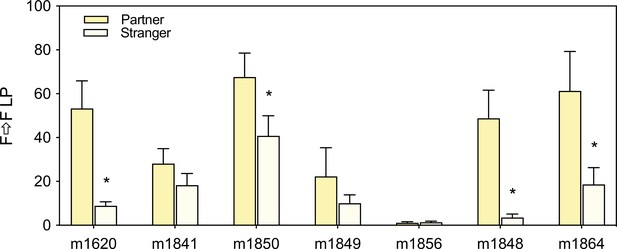

Individual lever pressing (LP) data for each prairie vole tested with a partner and stranger (8 days each).

Significant within-individual preference for the partner > stranger was present more often in female pressers (9/16) than in males (1/16; p = 0.0059, FET). Two males pressed significantly more for the stranger than the partner.

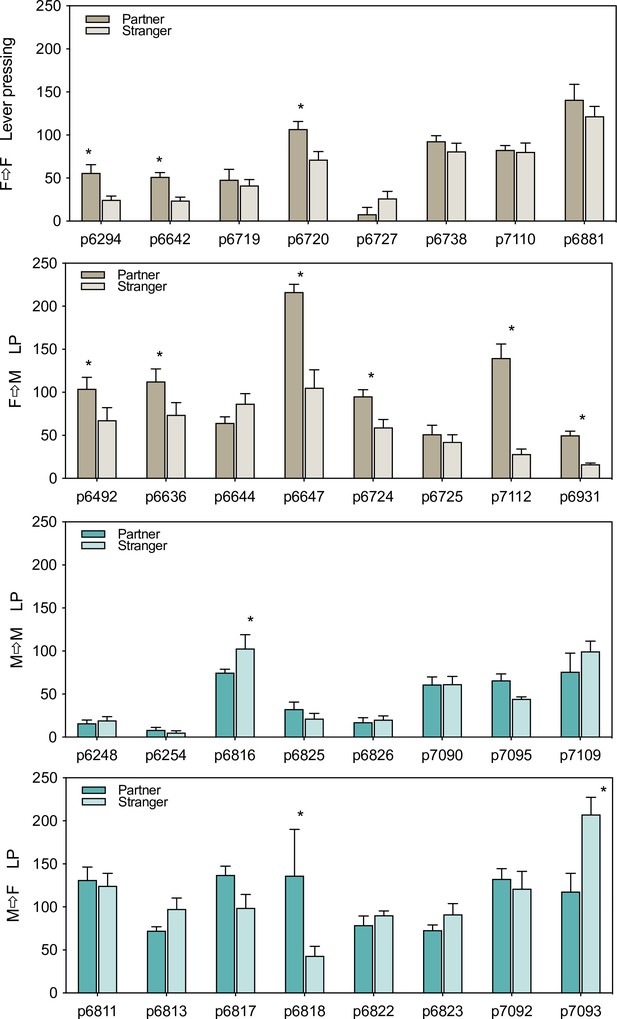

Affiliative and aggressive interactions with stimulus voles.

Data represent the 8-day testing mean for each vole (n = 8/group, ± SEM). (A,B) Percent of time focal voles spent in the social chamber relative to time when the door was open, allowing chamber access. Females shown in A, males in B. (C,D) Percent time spent huddling out of access time (i.e. when the door was raised). Significant effects of two-way repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA) are reported above each graph. Asterisks represent the results of within-groups paired t-tests. (E,F) Prairie voles exhibited significantly more bouts of aggression toward strangers (p < 0.0001), and there were no significant effects of sex of the presser or of the social target. (G) No relationship was present between daily lever pressing for access to strangers and aggression scaled by access time in male or female prairie voles. NS = not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

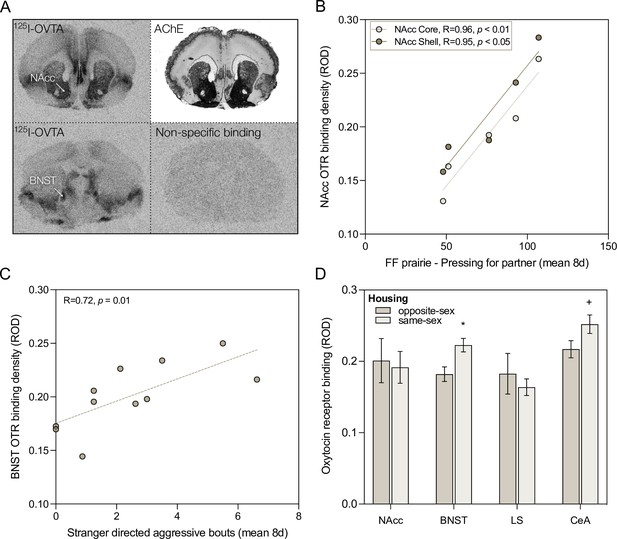

Oxytocin receptor (OTR) density, housing, and social behavior.

(A) Representative images of 125I-OVTA binding patterns in the brains of female prairie voles. The top row shows binding at the level of the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), and an adjacent acetylcholinesterase (AChE) stained section for anatomical verifications. The bottom row shows binding at the level of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and late lateral septum, as well as an adjacent section from the same brain processed for non-specific binding using the highly selective OTR antagonist [Thr4Gly7]-oxytocin. (B) OTR binding in the NAcc core and shell were strongly correlated with individual variation in lever pressing for a partner. (C) OTR binding in the BNST was positively correlated with stranger-directed aggression in females across pair types. (D) OTR density also varied in response to housing/pairing condition (opposite-sex versus same-sex). *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1.

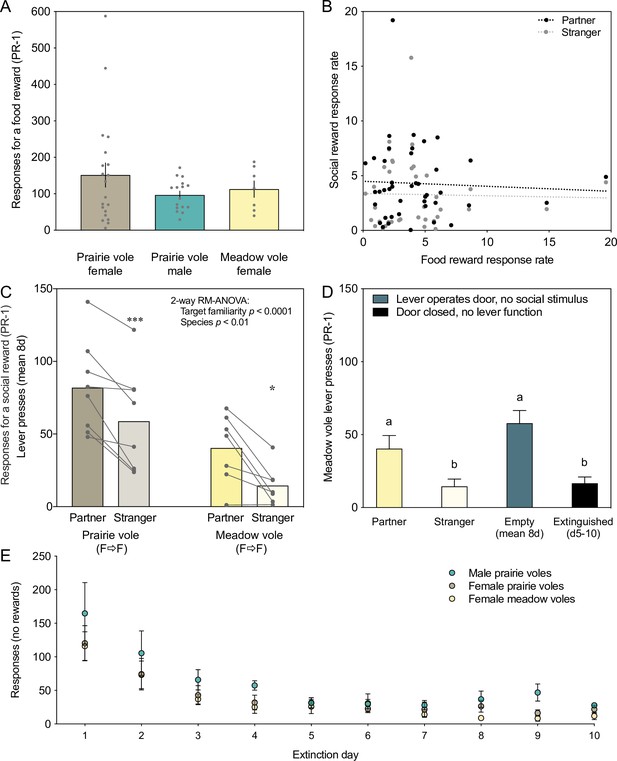

Quantifying responses across species, sexes, and reward types.

(A) Responses for a food reward did not significantly differ between prairie voles of different sexes or between meadow and prairie vole females. Each data point represents the 8-day mean of responses from a vole tested using a progressive ratio 1 (PR-1) schedule in 30-min sessions. (B) Food response rate did not predict social response rate for familiar or unfamiliar stimuli. Data points show prairie vole response rates for food pellets on a PR-1 schedule (8-day mean for each vole) versus social reward (black: partner; gray: stranger) on a PR-1 schedule (8-day mean for each vole). (C) Meadow voles, like prairie voles, pressed more for a partner than a stranger, but pressed significantly less overall. (D) Social pressing for a partner in meadow voles was no higher than pressing for an empty chamber, and stranger pressing was similar to the minimum achieved by extinction. (E) Extinction profile over 10 days for each species and sex tested. Lever presses diminished rapidly over the first 4–5 days of testing with an inactive lever.

Individual data for each meadow vole tested with a partner and stranger (8 days each).

Significant within-individual preference for the partner > stranger was detected in four of seven females. One female did not press at high levels for any social stimulus, despite high levels of responding for a food reward during earlier testing.

Tables

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical compound, drug | (Thr⁴,Gly⁷)-Oxytocin | Bachem | 4013837 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | 125I-OVTA; 125I-ornithine vasotocin analog; vasotocin, d(CH2)5 [Tyr(Me)2,Thr4,Orn8,(125I)Tyr9-NH2] | Perkin Elmer | NEX254050UC | |

| Chemical compound, drug | Testosterone | Sigma-Aldrich | T1500 | |

| Software, algorithm | MED-PC IV | Med Associates | SOF-735 |