The Natural History of Model Organisms: The big potential of the small frog Eleutherodactylus coqui

Figures

The indigenous Taíno symbol for coquí, which is ubiquitous in Puerto Rico.

The frog-like hands seen in Taíno imagery are associated with ‘femaleness’ and the calls of coquí are associated with female fertility and children (Ostapkowicz, 2015).

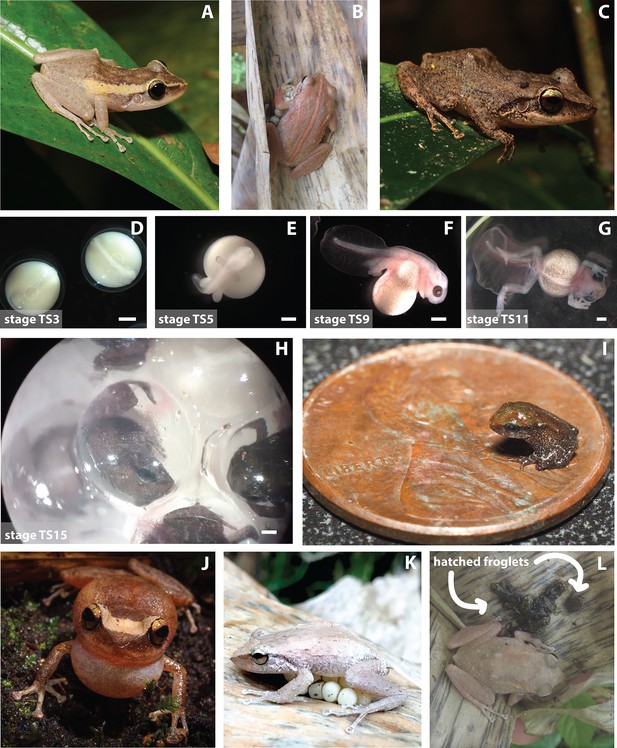

Different aspects of coquí natural history.

(A–C) Coquí vary in color and pattern across different localities. (D–H) Coquí are direct developers, skipping the tadpole stage in their early development from an egg to a froglet. Townsend-Stewart (TS) described coquí development in 15 stages. Scale bars are 1 mm. (I) Froglets are quite small when they hatch and are at risk of predation by invertebrates. (J) Coquí are particularly known for their noisy calls made with their elastic vocal sacs. (K–L) Male coquí sit on their terrestrial eggs to hydrate them and will guard their newly hatched froglets.

Image credits: (A, C) S Van Belleghem (B, K–L) K Harmon (D–H) M Laslo (I) C Brown, USGS (J) A Lopez.

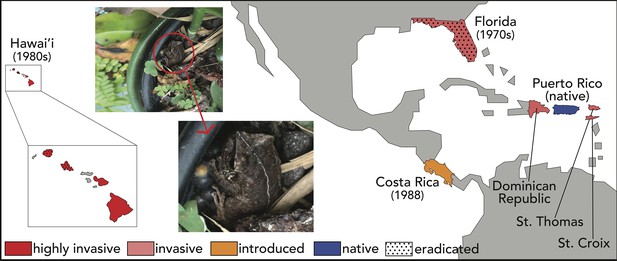

Distribution of the coquí.

Native to Puerto Rico, E. coqui have successfully invaded many tropical islands and countries. Close to home, coquí have been introduced to other Caribbean islands, including the Culebra and Vieques Islands of Puerto Rico (Rivero and Joglar, 1979), St. Thomas and St. Croix in the Virgin Islands (MacLean, 1982), and the Dominican Republic (Joglar, 1998). Farther afield, coquí were accidentally introduced to Florida in the 1970s (Austin and Schwartz, 1975; Wilson and Porras, 1983) and Hawai’i in the late 1980s (Velo-Antón et al., 2007), presumably as hitch-hikers on ornamental plants (photo inset). An intentional introduction of E. coqui was documented in Costa Rica, where six individuals were released in a private garden in 1998 and have since spread (Barrantes-Madriga et al., 2019). Floridian and some Hawaiian populations have been successfully eradicated due to inhospitable environmental conditions (Florida) and human effort (Hawai’i), but reintroductions remain a documented concern.

Image credit: RN Tischler.

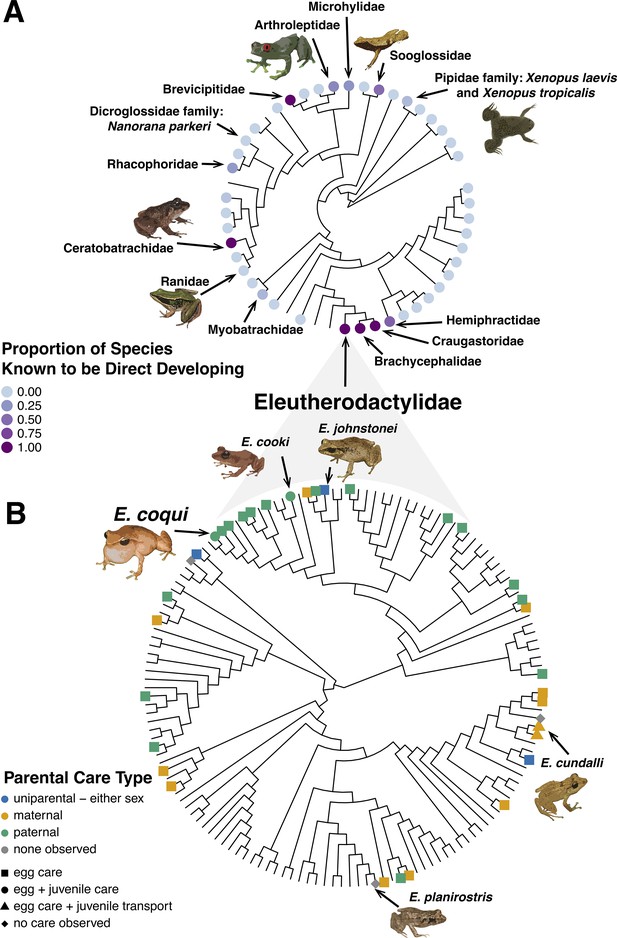

Evolution of direct development and parental care type.

(A) Phylogenetic tree showing that, across Anura, there have been 11 independent evolutionary occurrences of direct development. Evidence suggests that the clade that includes Eleutherodactylidae, Craugastoridae, and Hemiphractidae is one of the oldest direct developing lineages, having evolved ~71–108 MYA (see Heinicke et al., 2009 and Gomez-Mestre et al., 2012 more details on the evolution of direct development). Other instances of direct development appear to have emerged more recently. (B) Phylogenetic tree showing that, across the family Eleutherodactylidae, there is variation in parental care strategies, including maternal, paternal, and amphisexual. E. coqui sits within a larger clade with mostly paternal egg care; additionally, male coquí care for froglets. E. coqui is one of two Eleutherodactylid species known to show paternal egg and juvenile care (Furness and Capellini, 2019). Currently, data is too sparse and varied to determine what specific parental care strategy was used by the ancestor of Eleutherodactylids; however, parental care is generally associated with direct development and a terrestrial life history (Gomez-Mestre et al., 2012; Vági et al., 2019). Phylogenetic clade relationships created from Pyron, 2014 time tree data. Direct development and behavior traits mapped on phylogenies with data from Furness and Capellini, 2019.

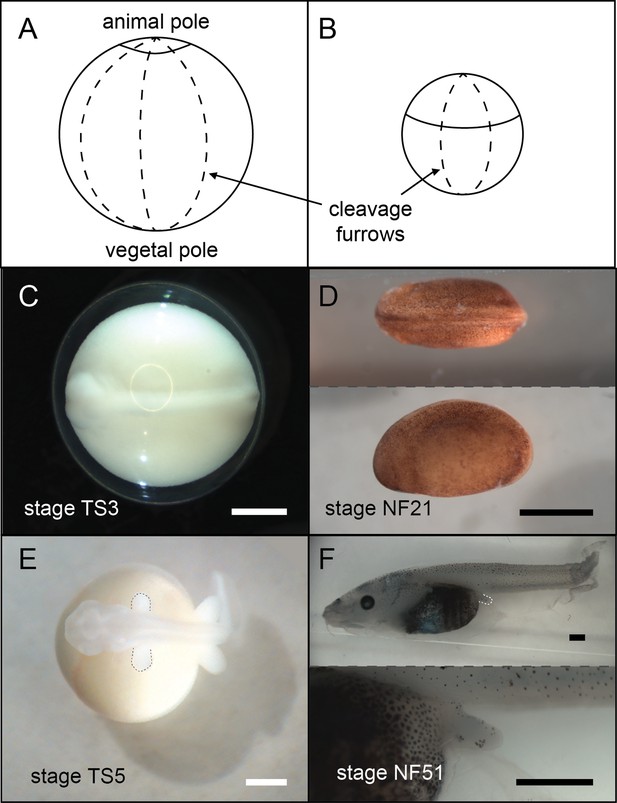

A comparison of E.coqui (A, C, E) and X. laevis (B, D, F) development.

(A–B) Drawings of embryos after the first horizontal division. This horizontal division divides the embryo into animal (top) and vegetal (bottom) cells. The cap of E. coqui animal cells is much smaller than the animal cells in the early X. laevis embryo. (C) Dorsal view of the E. coqui neurula, which is shifted towards the animal pole compared to the X. laevis neurula (D; dorsal and lateral views shown). (E–F) Morphologically equivalent limb bud stages of the coquí embryo (E) and the X. laevis embryo (F). The coquí embryo is atop a large yolk mass, while limb buds emerge from a free-swimming X. laevis tadpole. Scale bars are 1 mm.

Image credit: M Laslo.

Videos

Coquí are notorious in Puerto Rico for their loud vocalizations at night.

Video credit: K Harmon.