Amoxicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae can be resensitized by targeting the mevalonate pathway as indicated by sCRilecs-seq

Figures

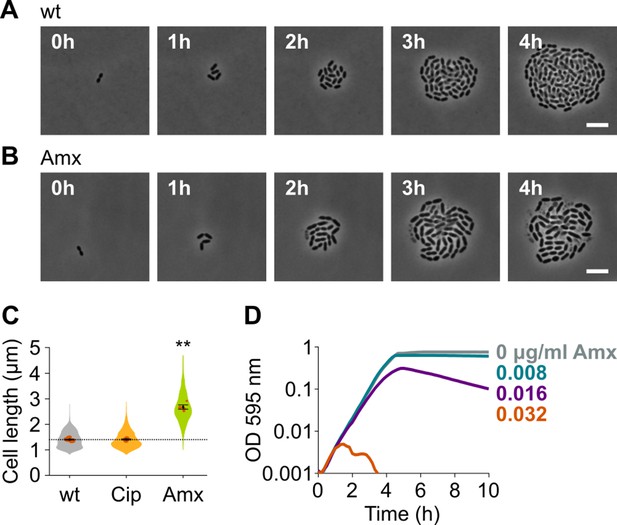

Amoxicillin causes cell elongation before triggering cell lysis.

(A) Snapshots of a time lapse phase contrast microscopy experiment of S. pneumoniae D39V growing in the absence of antibiotics (Video 1). (B) Snapshots of a time-lapse analysis of S. pneumoniae D39V growing in the presence of a sub-MIC concentration of amoxicillin (0.016 µg/ml) (Video 2). (C) The effect of sub-MIC concentrations of ciprofloxacin (0.5 µg/ml) and amoxicillin (0.016 µg/ml) on the cell length of S. pneumoniae D39V was tested by phase contrast microscopy after 2 hr of treatment. Quantitative analysis of micrographs shows that cell length increases upon treatment with amoxicillin. Data are represented as violin plots with the mean cell length of every biological repeat indicated with orange dots. The size of these dots indicates the number of cells recorded in each repeat, ranging from 112 to 1498 cells. Black dots represent the mean ± SEM of all recorded means, n≥3. Two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed against wt without antibiotic as control group (dotted line), and p values were adjusted with a false discovery rate (FDR) correction; ** p<0.01. (D) S. pneumoniae D39V was grown in the presence of different concentrations of amoxicillin, and growth was followed by monitoring OD 595 nm. wt: wildtype; Cip: ciprofloxacin; Amx: amoxicillin.

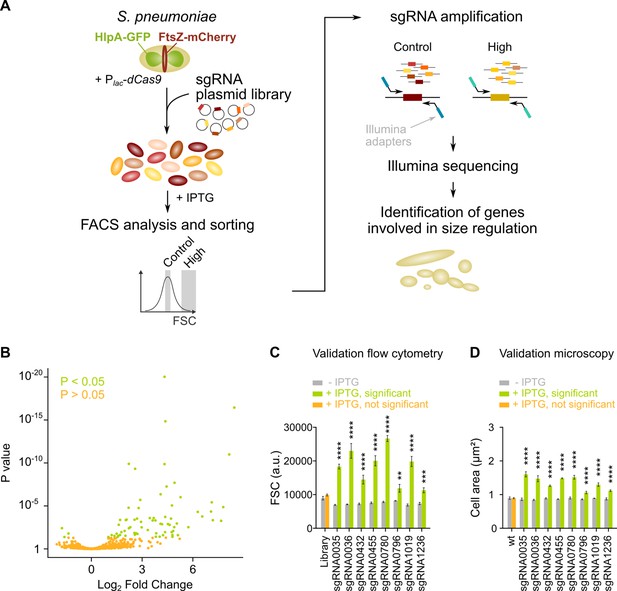

sCRilecs-seq (subsets of CRISPR interference libraries extracted by fluorescence activated cell sorting coupled to next generation sequencing) identifies operons involved in cell size regulation.

(A) A pooled CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) library was constructed in S. pneumoniae D39V Plac-dcas9 lacI hlpA-gfp ftsZ-mCherry (VL3117) by transformation of a plasmid library encoding 1499 constitutively expressed sgRNAs that together target the entire genome. This CRISPRi library was grown in the presence of IPTG for 3.5 hr to induce expression of dCas9, and cultures were sorted based on forward scatter (FSC) as a proxy for cell size. 10% of the population with the highest FSC values was sorted, as well as the centermost 70% of the population which served as a control. sgRNAs from sorted fractions were amplified by PCR using primers that contain Illumina adapters. Amplified sgRNAs were sequenced and mapped to the sgRNA library. sgRNA read counts were compared between the different sorted fractions to identify gene depletions that lead to increases in cell size. (B) A volcano plot shows the statistical significance and enrichment for every sgRNA in the fraction of the population with high FSC values compared to the control with normal FSC values. (C–D) Some of the most strongly enriched significant sgRNA hits were validated by studying individual mutants. (C) Flow cytometry measurements of mutants grown with and without IPTG were performed. The median FSC value for each depletion was recorded and compared to the median value of the same strain without induction of dCas9. Note that the entire CRISPRi library was also included in this experiment (‘Library’) as a control. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n=3. ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, and two-sided t-tests with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. (D) Quantitative analysis of microscopy images of CRISPRi depletion mutants with and without IPTG was performed. The mean of the mean cell area for each depletion was measured and compared to the same strain without induction of dCas9. Data are represented as mean of mean ± SEM, n=3 where each repeat consists of at least 50 cells. **** p<0.0001 and two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank tests with false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons.

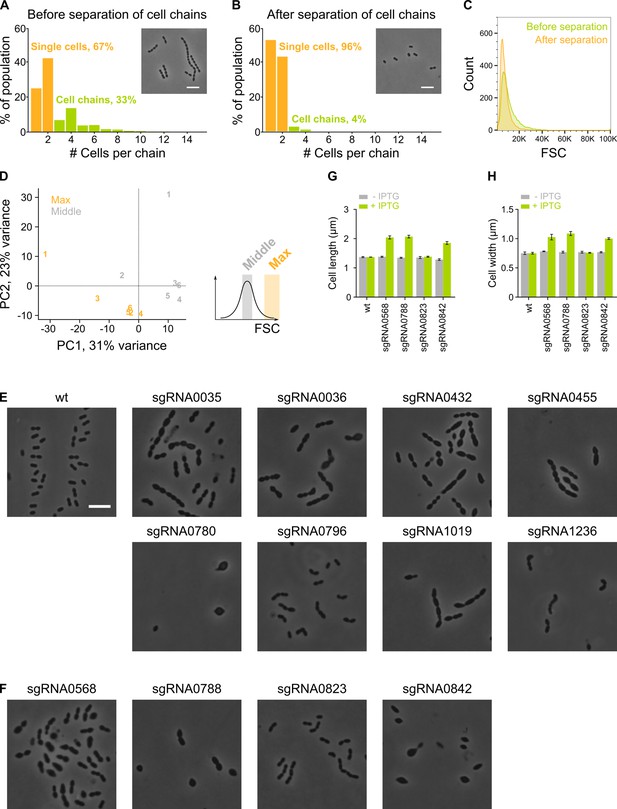

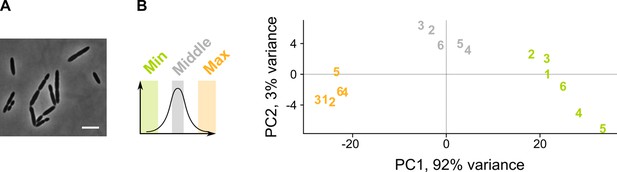

The sCRilecs-seq (subsets of CRISPR interference libraries extracted by fluorescence activated cell sorting coupled to next generation sequencing) screen started from mechanically separated single cells and displayed a high amount of variation.

(A–B) The amount of cell chains of VL3117 was determined by quantitative analysis of microscopy pictures before (A) and after (B) cell chains were mechanically disrupted. Cell chains were defined as containing more than two cells. Insets of microscopy pictures and quantitative analysis show that our cell chain disruption protocol is able to eliminate almost all chains. More than 400 cell chains were analyzed per condition. (C) Before and after mechanical disruption of S. pneumoniae cell chains, the forward scatter (FSC) of these cultures was determined by flow cytometry. FSC is indeed increased by the presence of cell chains. (D) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the sorted fractions with normal and high FSC values of the VL3117 CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) library shows that there is considerable variation between different repeats but different conditions are still well separated. Repeats are indicated with their assigned number. (E–F) Representative cells from individual CRISPRi depletions are shown. CRISPRi depletion strains with sgRNAs shown in (E) were among the most significantly enriched in the fraction of the population with increased cell length and were chosen for validation. sgRNAs shown in (F) were investigated because of their unexpected enrichment in the fraction of the population with the largest cell sizes. (G–H) The effect of selected individual CRISPRi depletions (shown in panel F) on cell length (G) and cell width (H) was determined by quantitative microscopy. Scale bar, 5 µm.

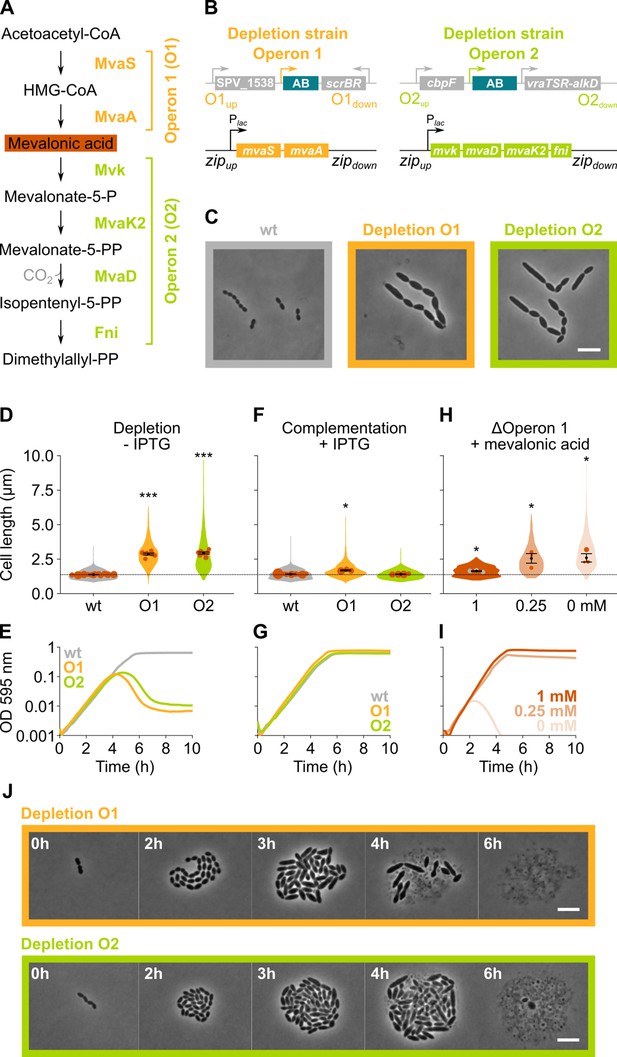

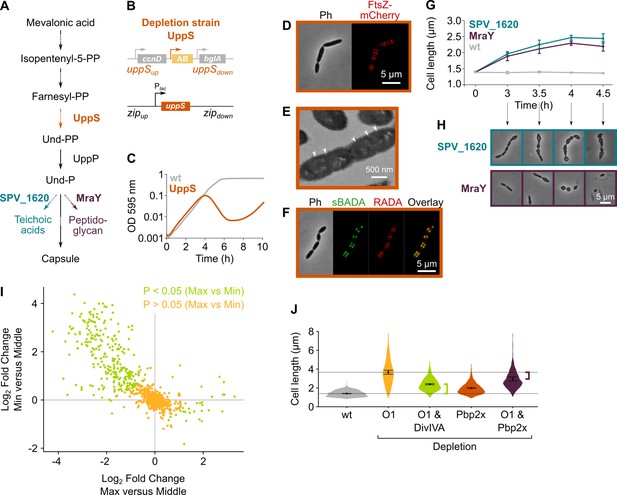

The mevalonate pathway is essential for S. pneumoniae and leads to cell elongation upon depletion.

(A) The mevalonate pathway and its genetic organization in S. pneumoniae is depicted. (B) A genetic representation of the mevalonate depletion strains are shown. The native mevalonate operons were deleted and replaced by an antibiotic marker (AB), and a complementation construct under control of the Plac promoter was inserted at the zip locus (Keller et al., 2019) in the S. pneumoniae genome. (C) Phase contrast microscopy images of liquid cultures of S. pneumoniae wildtype (wt) or upon depletion of one of the mevalonate operons for 4 hr in VL3565 and VL3567 are shown. Scale bar, 5 µm. (D) Quantitative analysis of phase contrast micrographs shows that cell length increased when mevalonate operons were depleted. Data are represented as violin plots with the mean cell length of every biological repeat indicated with orange dots. The size of these dots indicates the number of cells recorded in each repeat, ranging from 100 to 2626 cells. Black dots represent the mean ± SEM of all recorded means, n≥3. (E) Depletion of mevalonate operons led to a severe growth defect. Data are represented as the mean, n≥3. (F) The elongated phenotype upon depletion of mevalonate operons could be complemented by inducing their expression with IPTG. Data are represented as violin plots with the mean cell length of every biological repeat indicated with orange dots. The size of these dots indicates the number of cells recorded in each repeat, ranging from 100 to 2626 cells. Black dots represent the mean ± SEM of all recorded means, n≥3. (G) The growth defect associated with depletion of mevalonate operons could be fully complemented by inducing their expression with IPTG. Data are represented as the mean, n≥3. (H) A mutant in which the first mevalonate operon was deleted (VL3702, no complementation construct) displayed increased cell length when the concentration of mevalonic acid added to the growth medium was decreased. Data are represented as violin plots with the mean cell length of every biological repeat indicated with orange (or gray) dots. The size of these dots indicates the number of cells recorded in each repeat, ranging from 100 to 2626 cells. Black dots represent the mean ± SEM of all recorded means, n≥3. (I) Growing the mutant in which the first mevalonate operon is deleted (no complementation construct) with decreasing concentrations of external mevalonic acid led to an increasing growth defect, resulting in full extinction of the culture when no mevalonic acid was provided. Data are represented as the mean, n≥3. (J) Snapshot images of phase contrast time lapse experiments with mutants in which the first or second mevalonate operon was depleted (VL3565 and VL3567) are shown. Strains were grown on agarose pads of C+Y medium without the inducer IPTG. Scale bar, 5 µm. Two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed against wt – IPTG as control group (dotted line) and p values were adjusted with a false discovery rate (FDR) correction; * p<0.05 and *** p<0.001.

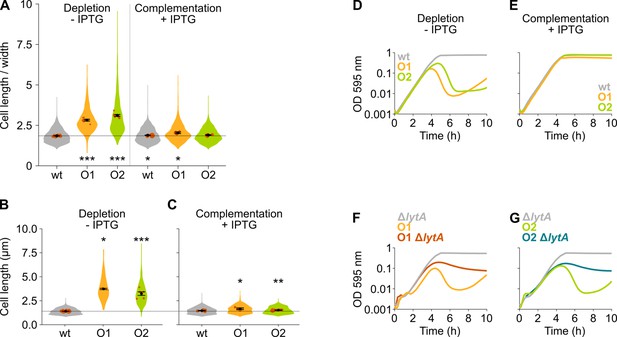

The mevalonate pathway is essential for S. pneumoniae and leads to cell elongation upon depletion.

(A) This panel shows the ratio of the cell length to cell width of S. pneumoniae hlpA-gfp ftsZ-mCherry (VL3404, wildtype [wt]) and depletion mutants of the first and second operon involved in mevalonate synthesis (O1/VL3567 and O2/VL3565, respectively). The mean cell length recorded in every biological repeat is indicated with orange dots. The size of these dots indicates the number of cells recorded in each repeat, ranging from 100 to 2626 cells. The black dots and error bars indicate the average of the mean cell lengths from different repeats ± SEM, n≥3. (B–C) Quantitative analysis of microscopy images of S. pneumoniae without the hlpA-gfp and ftsZ-mCherry fusion proteins (VL333, VL3708, and VL3709) shows that cell length increases when mevalonate operons are depleted (B) and that normal cell length is restored by complementation (C). Data are represented as violin plots with the mean cell length from every biological repeat indicated with orange dots. The size of these dots indicates the number of cells recorded in each repeat, ranging from 15 to 1498 cells. The average of the mean cell lengths from different repeats ± SEM, n≥3 is indicated with a black dot and error bars. (D) Depletion of mevalonate operons in VL3708 and VL3709 led to a severe growth defect. Data are represented as the mean, n≥3. (E) The growth defect associated with depletion of mevalonate operons could be fully complemented by inducing their expression with IPTG. Data are represented as the mean, n≥3. (F–G) Lysis upon depletion of the mevalonate operon 1 (F) or 2 (G) was investigated in the presence and absence of the lytA gene. Data are represented as the mean, n=3. Two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed against wt – IPTG as control group and p values were adjusted with a false discovery rate (FDR) correction; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001.

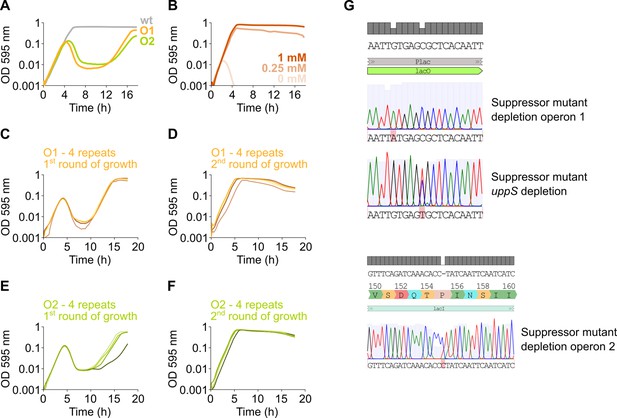

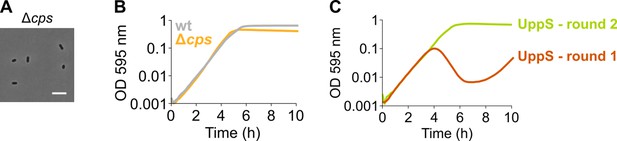

Suppressor mutants arise due to mutations in lacI or Plac.

(A) After an extended period of growth, depletion strains of mevalonate operon 1 and 2 (native operon deleted and replaced by an IPTG-inducible copy elsewhere in the genome) display growth after an initial phase of lysis, indicating the presence of suppressor mutants. (B) No growth occurs when assessing an operon 1 deletion strain (native operon deleted, no inducible copy elsewhere in the genome), even after an extended period of growth, indicating that no suppressor mutations occur. (C–F) To confirm the presence of suppressor mutations that alleviate the dependency of growth on the presence of IPTG, depletion strains of mevalonate operon 1 (C–D) and 2 (E–F) were grown for two consecutive rounds without IPTG. In the first round of growth (C, E), for all four independent repeats, lysis occurs due to the depletion of the respective operons and is followed by growth. Next, resulting cultures were diluted 100× and subjected to a second round of growth (D, F). Here, lysis no longer occurs indicating that these cultures are no longer dependent on IPTG for growth and have obtained suppressor mutations. (G) Sequencing of some of these suppressors revealed mutations in the lacO operator of the Plac promoter or the lacI repressor.

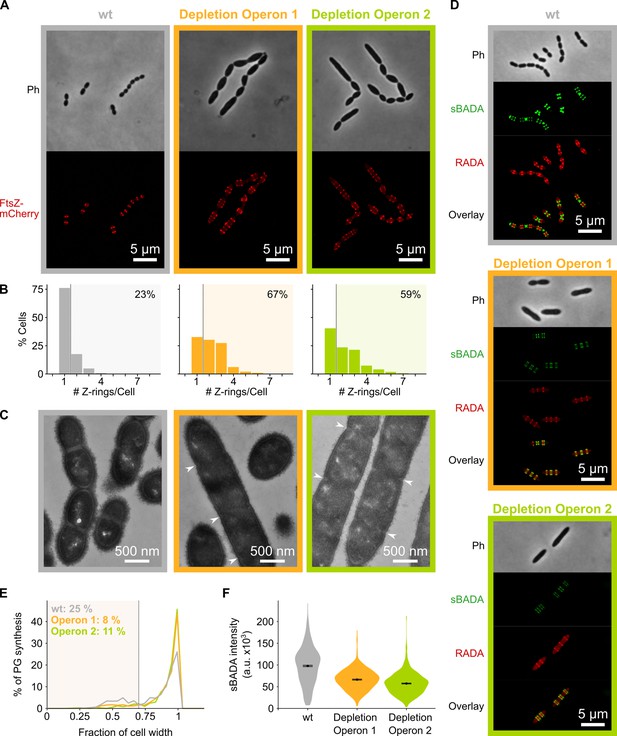

Depletion of mevalonate operons prevents cell division.

(A) While S. pneumoniae wild-type (wt) cells typically contain one FtsZ ring at the cell center, depletion of either one of the mevalonate operons led to strongly elongated cells with multiple unconstricted FtsZ rings. Images were obtained using strains VL3404, VL3565, and VL3567 that encode the ftsZ-mCherry fusion. (B) Quantitative analysis of microscopy pictures was used to determine the number of Z-rings per cell. Pictures from at least six independent repeats were analyzed, each including over 100 cells. (C) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show that elongated cells contained many initiated septa that appear to be blocked in further progression of constriction (white arrow heads). Images were obtained using strains VL333, VL3708, and VL3709 that do not encode fluorescent fusion proteins. (D) Pulse labeling S. pneumoniae with the green fluorescent D-amino acid (FDAA), sBADA, and 15 min later with the red RADA shows sites of active peptidoglycan synthesis involved in either elongation or constriction. Images were obtained using strains VL333, VL3708, and VL3709 that do not encode fluorescent fusion proteins. In overlay images, sBADA and RADA intensities were freely adjusted to produce the clearest images. Intensities in individual channels were not manipulated. (E–F) Quantitative image analysis of sites of active peptidoglycan synthesis labeled with FDAAs shows that depletion of mevalonate operons eliminated septal peptidoglycan synthesis since virtually no narrow sBADA or RADA bands can be found (E) and that the intensity of FDAA labeling decreased upon mevalonate depletion, indicating that peripheral peptidoglycan synthesis was slowed down (F). sBADA intensity is represented as the total intensity per cell. Number of sBADA bands analyzed for each condition >400.

Depletion of the mevalonate pathway likely prevents cell division by decreasing the amount of peptidoglycan precursors available for cell wall synthesis.

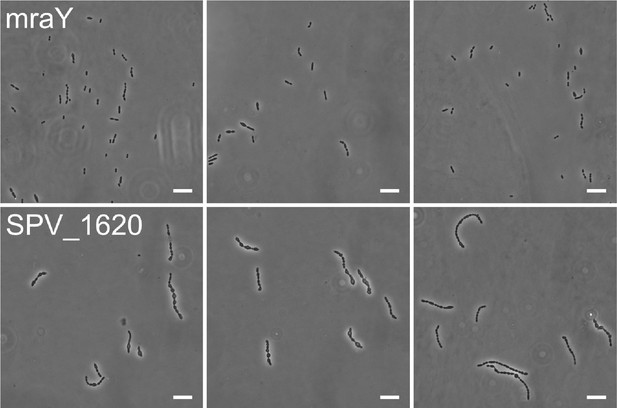

(A) After conversion of mevalonic acid into the basic isoprenoid building block isopentenyl-5-PP in the mevalonate pathway, this building block is condensed into the C15 molecule farnesyl-PP. Farnesyl-PP can be used by undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (UppS) for the production of undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (Und-PP), which after dephosphorylation to undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P) by UppP acts as the lipid carrier for the transport of precursors of peptidoglycan, the capsule, and teichoic acids across the cell membrane. (B) A genetic overview of the UppS depletion strains is shown. The native uppS gene was replaced by an antibiotic marker (AB), and a complementation construct under control of the Plac promoter was inserted at the zip locus in the S. pneumoniae genome. (C) Depletion of UppS in VL3584 caused a growth defect similar to depletion of the mevalonate operons. We confirmed that the growth observed after an initial phase of lysis was due to suppressor mutants that are no longer sensitive to UppS depletion (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C). Data are represented as averages, n≥3. (D) Like depletion of the mevalonate operons, depletion of UppS caused an elongated phenotype where cells contained multiple unconstricted FtsZ rings. Images were obtained using strain VL3585 which encodes ftsZ-mCherry. (E) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show that cells elongated due to UppS depletion contained many initiated septa that appeared to be blocked in further progression of constriction (white arrow heads). Images were obtained using strain VL3710 that does not encode fluorescent fusion proteins. (F) Pulse labeling S. pneumoniae depleted for UppS with the green FDAA, sBADA, and subsequently with the red RADA dye showed sites of active peptidoglycan synthesis, which are in this case all directed at cell elongation. Images were obtained using strain VL3710 that does not encode fluorescent fusion proteins. In the overlay, sBADA and RADA intensities were freely adjusted to produce the clearest image. Intensities in individual channels were not manipulated. (G) The effect of the depletion of MraY and SPV_1620 on cell length was followed through time using quantitative image analysis. For each biological repeat (n≥3), more than 50 cells were used to calculate the average cell length. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM of these averages. (H) Representative morphologies of VL3585 and VL3586 corresponding to the analysis from panel G are shown. (I) A pooled CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) library was constructed in VL3834 (S. pneumoniae D39V Plac-dCas9 ΔmvaA-mvaS). This CRISPRi library was grown in the presence of the dCas9 inducer, IPTG, and limiting amounts of mevalonic acid (100 µM). Cultures were sorted based on cell size (forward scatter [FSC]); 10% of the population with the highest and lowest values were sorted, as well as the centermost 70% of the population, which served as a control. sgRNAs from the sorted fractions were sequenced, and read counts were compared to identify gene depletions that led to changes in cell size. This plot shows the log2 fold change of sgRNAs in different conditions and their statistical significance when the fraction with the highest FSC values (Max) was compared to the fraction of the population with the lowest FSC values (Min). (J) Quantitative analysis of microscopy images shows the changes in cell length upon single or double depletions of the first mevalonate operon (O1, mvaS-mvaA), DivIVA, or Pbp2x. Data are represented as violin plots with the mean ± SEM indicated, n≥3, with each repeat containing >90 cells except for the double O1 Pbp2x depletion where not enough surviving cells could be visualized and the threshold was put at 10 cells.

An S. pneumoniae Δcps mutant that is unable to produce capsule does not display an elongated phenotype nor a growth defect.

(A) S. pneumoniae Δcps (VL567) has a normal morphology, although chaining is strongly decreased as expected. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) A strain unable to produce any capsule does not show a growth defect. (C) A growth curve of a undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (UppS) depletion strain (VL3584, round 1) shows an increase in OD at late time points due to suppressor mutants taking over. The existence of suppressor mutants was confirmed by re-inoculating cells from round 1 for a second round of growth under the same conditions. Data are represented as averages, n≥3.

A sCRilecs-seq (subsets of CRISPR interference libraries extracted by fluorescence activated cell sorting coupled to next generation sequencing) screen on mevalonate depleted cells to study the underlying genetic network.

(A) A pooled CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) library of S. pneumoniae D39V Plac-dCas9 Δoperon 1 (ΔmvaS-mvaA, VL3834) was grown in the presence of limiting amounts of mevalonic acid (100 µm) which leads to the elongated phenotype imposed by mevalonate deficiency. Scale bar, 5 µm. (B) Principle component analysis (PCA) of the sorted fractions of the population (fractions with the lowest and highest forward scatter [FSC] values, and a control with intermediate values) shows that different conditions are well separated. Repeats are indicated with their assigned number.

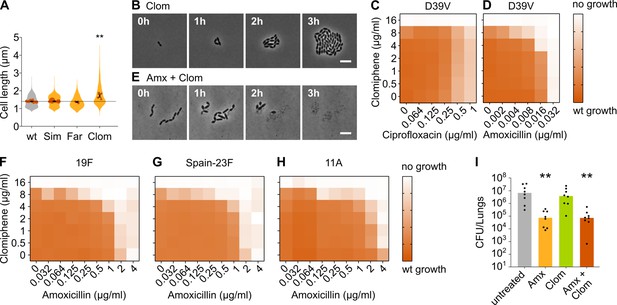

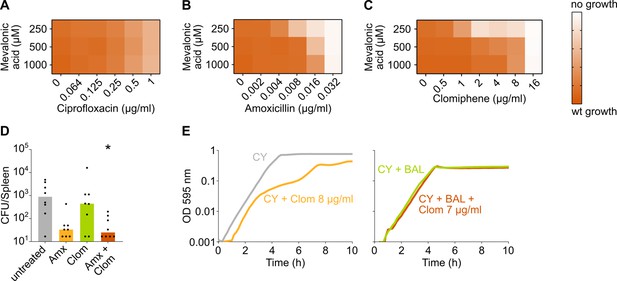

Clomiphene, an inhibitor of undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P) production, potentiates amoxicillin.

(A) The effect of several potential inhibitors of Und-P production on the cell length of S. pneumoniae D39V (VL333) was tested (Sim 4 µg/ml, Far 4 µg/ml, and Clom 8 µg/ml). Quantitative analysis of microscopy images shows that cell length increased upon treatment with clomiphene. Data are represented as violin plots with the mean cell length of every biological repeat indicated with orange dots. The size of these dots indicates the number of cells recorded in each repeat, ranging from 177 to 6464 cells. Black dots represent the mean ± SEM of all recorded means, n≥3. Two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed against wt without treatment as control group (dotted line), and p values were adjusted with a false discovery rate (FDR) correction; ** p<0.01. (B) Snapshot images of phase contrast time-lapse microscopy of S. pneumoniae D39V (VL333) in the presence of clomiphene (8 µg/ml). Scale bar, 5 µm. (C–D) OD595nm growth curves were constructed for S. pneumoniae D39V (VL333) in the presence of different concentrations of clomiphene and ciprofloxacin (C) or amoxicillin (D). Heatmaps of the area under the resulting growth curves are shown. Number of biological repeats for all experiments, n≥3. (E) Snapshot images of phase contrast time-lapse microscopy of S. pneumoniae D39V (VL333) in the presence of clomiphene (8 µg/ml) and amoxicillin (0.016 µg/ml). Scale bar, 5 µm. (F–H) OD595nm growth curves were constructed for S. pneumoniae 19F (F), Spain-23F (G), and 11A (H) in the presence of different concentrations of clomiphene and amoxicillin. Heatmaps of the area under the resulting growth curves are shown. Number of biological repeats for all experiments, n≥3. (I) The effect of the combination treatment with amoxicillin and clomiphene was tested in vivo using a pneumonia superinfection model with a clinical isolate of S. pneumoniae serotype 19F. Mice (n=8 per group) were infected intranasally first with H3N2 virus and then 7 days later with pneumococcus 19F. Mice were treated at 8 hr and 12 hr with clomiphene, amoxicillin, combination of both, or left untreated. Lungs were collected 24 hr post-infection to measure the bacterial load. CFU counts for individual mice are shown, and the bars represent the median value. The data were compared in a Kruskall-Wallis test (one-way ANOVA), ** p<0.01. wt: wildtype; Sim: simvastatin; Far: farnesol; Clom: clomiphene; Amx: amoxicillin.

The negative effect of clomiphene, methicillin, and amoxicillin on growth is exacerbated by mevalonate depletion.

(A–C) OD595nm growth curves were constructed for S. pneumoniae D39V in which the first mevalonate operon was deleted (VL3702). Cultures were grown in the presence of different amounts of externally added mevalonic acid and ciprofloxacin (A), amoxicillin (B), or clomiphene (C). Heatmaps of the area under the resulting growth curves are shown. Number of biological repeats, n≥3. (D) The effect of the combination treatment with amoxicillin and clomiphene was tested in vivo using a pneumonia superinfection model with a clinical isolate of S. pneumoniae serotype 19F. Mice (n=8 per group) were infected intranasally first with H3N2 virus and then 7 days later with pneumococcus 19F. Mice were treated at 8 hr and 12 hr with clomiphene, amoxicillin, combination of both, or left untreated. The spleen was collected 24 hr post-infection to measure the bacterial load. CFU counts for individual mice are shown, and the bars represent the median value. The data were compared in a Kruskall-Wallis test (one-way ANOVA), * p<0.05. (E) In vitro growth curves of S. pneumoniae D39V were constructed in C+Y medium (CY) or in C+Y medium supplemented with BAL fluid from mice treated with clomiphene (1:4). The amount of additional clomiphene added is indicated. Since adding 7 µg/ml clomiphene to S. pneumoniae growing in C+Y medium supplemented with 1:4 BAL fluid does not result in the same growth defect as adding 8 µg/ml clomiphene, we can conclude that the active concentration of clomiphene in undiluted BAL fluid is lower than 4 µg/ml. wt: wildtype; Amx: amoxicillin; Clom: clomiphene; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage.

Videos

Streptococcus pneumoniae D39V (VL333) growing on agarose pads of C+Y medium without added compounds.

Streptococcus pneumoniae D39V (VL333) growing on agarose pads of C+Y medium supplemented with 0.016 µg/ml amoxicillin.

An S. pneumoniae mutant strain where the first mevalonate operon was depleted (VL3709) growing on agarose pads of C+Y medium without the inducer IPTG.

An S. pneumoniae mutant strain where the second mevalonate operon was depleted (VL3708) growing on agarose pads of C+Y medium without the inducer IPTG.

An S. pneumoniae D39V (VL333) growing on agarose pads of C+Y medium supplemented with 8 µg/ml clomiphene.

An S. pneumoniae D39V (VL333) growing on agarose pads of C+Y medium supplemented with 0.016 µg/ml amoxicillin (left), 8 µg/ml clomiphene (middle), or both 0.016 µg/ml amoxicillin and 8 µg/ml clomiphene (right).

Tables

MIC values for amoxicillin/clomiphene and ciprofloxacin/clomiphene drug combinations (µg/ml).

| Clomiphene | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 µg/ml | 4 µg/ml | 8 µg/ml | |

| S. pneumoniae D39V | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Amoxicillin | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.004 |

| S. pneumoniae 19F | |||

| Amoxicillin | 2 | 1 | 0.125 |

| S. pneumoniae Spain-23F | |||

| Amoxicillin | 2 | 1 | 0.032 |

| S. pneumoniae 11A | |||

| Amoxicillin | 4 | 2 | 0.125 |

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain and strain background (S. pneumoniae) | D39V | doi:10.1093/nar/gky725 | VL001 | Serotype 2 and wildtype |

| Strain and strain background (S. pneumoniae) | 19F | This paper | VL4303 | Serotype 19F and clinical isolate |

| Strain and strain background (S. pneumoniae) | Spain-23F | German National Reference Center for Streptococci | VL1306 | Serotype 23F, PMEN1, and clinical isolate |

| Strain and strain background (S. pneumoniae) | 11A | German National Reference Center for Streptococci, doi:10.1093/jac/dky305 | VL1313 | Serotype 11A, PMEN3, and clinical isolate |

| Strain and strain background (Mus musculus) | C57BL/6JRj, male, 8 weeks old | Janvier Laboratories, Saint Berthevin, France | ||

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL333 | Veening lab collection | VL333 | D39V prs1::lacI-tetR-Gm |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL567 | doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00903-y | VL567 | D39V Δcps::Cm |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL1630 | Veening lab collection | VL1630 | D39V ftsZ-mCherry-Ery bgaA::Pzn-gfp-stkP |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL1998 | doi:10.15252/msb.20167449 | VL1998 | D39V prs1::F6-lacI-Gm bgaA::Plac-dCas9-Tc |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL2226 | doi:10.1128/JB.02221-14 | VL2226 | D39V hlpA-gfp-Cm |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3117 | This paper | VL3117 | VL1998 hlpA-gfp-Cm ftsZ-mCherry-Ery |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3404 | This paper | VL3404 | VL333 hlpA-gfp-Cm ftsZ-mCherry-Ery |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3565 | This paper | VL3565 | VL3404 zip::Plac-mvk-mvaD- mvaK2-fni-Spec Δmvk-mvaD-mvaK2-fni::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3567 | This paper | VL3567 | VL3404 zip::Plac-mvaS- mvaA-Spec ΔmvaS-mvaA::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3584 | This paper | VL3584 | VL3404 zip::Plac-uppS- Spec ΔuppS::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3585 | This paper | VL3585 | VL3404 zip::Plac-mraY-Spec ΔmraY::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3586 | This paper | VL3586 | VL3404 zip::Plac-SPV_1620- Trm ΔSPV_1620::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3671 | This paper | VL3671 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA035 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3672 | This paper | VL3672 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA036 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3673 | This paper | VL3673 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA046 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3674 | This paper | VL3674 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA087 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3675 | This paper | VL3675 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA100 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3676 | This paper | VL3676 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA121 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3677 | This paper | VL3677 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA135 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3678 | This paper | VL3678 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA355 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3679 | This paper | VL3679 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA432 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3680 | This paper | VL3680 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA455 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3681 | This paper | VL3681 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA460 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3682 | This paper | VL3682 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA461 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3683 | This paper | VL3683 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA503 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3684 | This paper | VL3684 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA573 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3685 | This paper | VL3685 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA583 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3686 | This paper | VL3686 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA590 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3687 | This paper | VL3687 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA628 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3688 | This paper | VL3688 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA673 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3689 | This paper | VL3689 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA757 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3690 | This paper | VL3690 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA780 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3691 | This paper | VL3691 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA785 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3692 | This paper | VL3692 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA796 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3693 | This paper | VL3693 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA813 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3694 | This paper | VL3694 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA822 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3695 | This paper | VL3695 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA824 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3696 | This paper | VL3696 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA900 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3697 | This paper | VL3697 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA1019 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3699 | This paper | VL3699 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA1064 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3700 | This paper | VL3700 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA1236 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3701 | This paper | VL3701 | VL3117 zip::P3-sgRNA1240 |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3702 | This paper | VL3702 | VL333 ΔmvaS-mvaA::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3708 | This paper | VL3708 | VL333 zip::Plac-mvk-mvaD- mvaK2-fni-Spec Δmvk- mvaD-mvaK2-fni::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3709 | This paper | VL3709 | VL333 zip::Plac-mvaS- mvaA-Spec ΔmvaS-mvaA::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3710 | This paper | VL3710 | VL333 zip::Plac-uppS- Spec ΔuppS::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3711 | This paper | VL3711 | VL333 zip::Plac-mraY-Spec ΔmraY::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3712 | This paper | VL3712 | VL333 zip::Plac-SPV_1620- Trm ΔSPV_1620::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL3834 | This paper | VL3834 | VL1998 ΔmvaS-mvaA::Km |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL4273 | This paper | VL4273 | VL333 bgaA::Ptet-pbp2x-Tc Δpbp2x::Ery |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | VL4274 | This paper | VL4274 | VL3709 bgaA::Ptet-pbp2x-Tc Δpbp2x::Ery |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | LD0001 | This paper | LD0001 | VL333 bgaA::Ptet-divIVA-Tc ΔdivIVA::Cm |

| Genetic reagent (S. pneumoniae) | LD0002 | This paper | LD0002 | VL3709 bgaA::Ptet-divIVA-Tc ΔdivIVA::Cm |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL47 | This paper | PCR primer | GATTGTAACCGATTCATCTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL48 | This paper | PCR primer | GGAATGCTTGGTCAAATCTA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL898 | This paper | PCR primer | CCAACAAGCTTCA CAAAATAAACCG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL901 | This paper | PCR primer | CTTATCCGTTGCACGCTGACTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL1369 | This paper | PCR primer | GTCTTCTTTTTTACCTT TAGTAACTACTAATCCTGCAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL2077 | This paper | PCR primer | ATTCCTTCTTAA CGCCCCAAGTTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL2181 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCA GCATTATTTTTC CTCCTTATTTAT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL2182 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCACG GATCCCTCCAGT AACTCGAGAA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL2933 | This paper | PCR primer | GATCGGTCTCGAG GAATTTTCATATGAA CAAAAATATAAAATATTCTCAA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL2934 | This paper | PCR primer | GATCGGTCTCGTT ATTTCCTCCCGTTAA ATAATAGATAAC TATTAAAAAT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3493 | This paper | PCR primer | GCCAATAAATTGC TTCCTTGTTTT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3496 | This paper | PCR primer | ATGACACGGATTTT AAGAATAATTCTTTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3649 | This paper | PCR primer | TGTGTGGCTCTTCG AGAACTCGAGAAAA AAAAACCGCGCCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3650 | This paper | PCR primer | TGTGTGGCTCTTCG GTTTCATTATTTTT CCTCCTTATTTATTT AGATCTTAATTGTGAGC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3671 | This paper | PCR primer | CTGGTAGCTCTTCCA ACATGCTGAAATGGG AAGACTTGCCTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3672 | This paper | PCR primer | CTGGTAGCTCTTCCT CTTTATTTTAGTACCT CAAACACGGTT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3677 | This paper | PCR primer | GTATAGTAAGCTGG CAGAGAATATC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3680 | This paper | PCR primer | ATACTTTTTAGGGA CAGGATCAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3958 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAT GCTCGTCTAGTAAAA GGAAAAAATGACAAAAAAA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3959 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATC CGTTACGCCTTTTTC ATCTGATCATTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3962 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAATG CAGTATAGAACGATTTT TTACATGAATGATAAAACAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3963 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATCC GTTATGATCTTAAATTT TCGAGATAGCGCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3981 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAT GGCTAAAATGAGAA TATCACCGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3982 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCACTA AAACAATTCATCCAGTA AAATATAATATTTTATTTTCTCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL3983 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAGA GGACGCGCAAGCTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4061 | This paper | PCR primer | CACTACCAATTGG TGAAGTTGCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4062 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCACCT CTTTTTCCTTTTACTA GACGAAAAAACGTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4063 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAT TAGGGCGTAACCAGCGCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4064 | This paper | PCR primer | TACAGGTACGAT GATTTTGGTCGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4069 | This paper | PCR primer | AGCTGAAGATAAA GCCTGTAACCA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4070 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAC CATGTAAAAAATCGT TCTATACTATTTT ATCACAAATGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4071 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATT AGCATAAAAACTCA GACGAATCGGTCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4072 | This paper | PCR primer | ACAGCGCCGATTATTTCCTTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4341 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAT TTATTTAGATCTTAA TTGTGAGCGCTC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4583 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAAA TTTTTGAATAGGAATAA GATCATGTTTGGATTTT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4584 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATCC GCTAAACTCCTCCA AATCGGCG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4585 | This paper | PCR primer | TCCAGATTTTTCTTAT GAGGAAACCTTATT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4586 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAC CATGATCTTATTCCT ATTCAAAAATCTA TCGTTTCATT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4587 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATT AGGGAGGAGTTTAG GAGGAAATATGACC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4588 | This paper | PCR primer | CTGTACTGTCAACT ATCATAAAGATAATGGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4595 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAA ATATTAACTTTAGGAG ACTAATATGTTTATTTCCATCAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4596 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATC CGTTACATCAAATAC AAAATTGCGAGGGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4597 | This paper | PCR primer | AGATTGCTGACGA GAAAAATGGTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4598 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCACC ATATTAGTCTCCTAAA GTTAATGTAATTTT TTTAATGTCC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4599 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATT AGGAATGGCACCC TGATGTTTCA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4600 | This paper | PCR primer | AATAAATCATCCATG TTGTTAAAATTATT AAAATTGTTGT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4601 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAC CATGCTGTTCTCC TTTGTTTTTATTATAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL4602 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCATT AGAGTAGTCATAAG AAAATGAGTACAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5705 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCAAT TTATTTAGATCTACTCT ATCAATGATAGAG TTATTATACTCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5706 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCAGC GTAAGGAAATCCATTA TGTACTATTTCTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5707 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCAAAA TTTAAGTAAGTGAGGA ATAGAATGCCAATTACA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5708 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCAAC GCCTACTTCTGGTTC TTCATACATTGGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5717 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAT TTATTTAGATCTACTCT ATCAATGATAGAG TTATTATACTCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5718 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAGC GTAAGGAAATCCATT ATGTACTATTTCTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5727 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCAAT GAACTTTAATAAAATT GATTTAGACAATTGGAAGAG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5728 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCAT TATAAAAGCCAGTC ATTAGGCCTATCT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5729 | This paper | PCR primer | CTCCTTTTTTAACTCC TTTTATCAATCCTCA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5730 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCATCAT TCTATTCCTCACTTACT TAATAATAACTGGACG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5731 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCAGGTCTCAATAA CTCCAGTGCATCCGACAGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL5732 | This paper | PCR primer | ACCAAGTCCATTTCTTTACGTTTGAC |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL6214 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGCGTAAGATTGAGCAA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL6215 | This paper | PCR primer | GATCGGTCTCATCCT ATCTTACTCCGCT ATTCTAATATTTTCA |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL6216 | This paper | PCR primer | GATCGGTCTCGATAAAT CAAGGACATTAAAAA AATTACATTAACTT |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL6217 | This paper | PCR primer | ACATCACCCATAAAGACCTTG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL6276 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAAA TTTAGAATAGCGGAG TAAGATATGAAGTGG |

| Sequence-based reagent | OVL6277 | This paper | PCR primer | GCGTCACGTCTCAAC GCTTAGTCTCCTAAAGT TAATGTAATTTTTTTAATGTCC |

| Chemical compound and drug | Mevalonic acid lithium salt | Bio-Connect BV (BIPP) | HY-113071A | |

| Chemical compound and drug | Clomiphene citrate salt | Sigma - Aldrich | C6272 | |

| Chemical compound and drug | Clomid | Sanofi-Aventis | Clomiphene citrate tablets USP, 50 mg tablets, used for in vivo assays | |

| Chemical compound and drug | Amoxicillin | GlaxoSmithKline | Clamoxyl for injection, used for in vivo assays | |

| Chemical compound and drug | sBADA | Tocris Bioscience | 6659 | Work concentration 250 µM |

| Chemical compound and drug | RADA | Tocris Bioscience | 6649 | Work concentration 250 µM RRID:SCR_014237 |

| Software and algorithm | 2FAST2Q | doi:10.1101/2021.12.17.473121 | https://github.com/veeninglab/2FAST2Q; Veening Lab, 2022a | |

| Software and algorithm | DESeq2 | doi:10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html | |

| Software and algorithm | Fiji (Fiji Is Just ImageJ) | doi:10.1038/nmeth.2019 | https://imagej.net/software/fiji/downloads | |

| Software and algorithm | Huygens software | Scientific Volume Imaging | https://svi.nl/Huygens-Software | |

| Software and algorithm | MicrobeJ | doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.77 | https://www.microbej.com/ | |

| Software and algorithm | BactMAP | doi:10.1111/mmi.14417 | https://github.com/veeninglab/BactMAP; Veening Lab, 2022b |

| sgRNA | Target | Log2FC | Adjusted P value | Screen | Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA0557 | relA | -1,611951038 | 0,188689 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA | Target | Log2FC | Adjusted P value | Screen | Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA0688 | SPV_2427, comGG, comGF, comGE, comGD, comGC, comGB, comGA | -0,54399 | 0,817735 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA0764 | tRNA-Glu-5, comE, comD, comC1 | -1,16648 | 0,134294 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA0863 | comX2, comX1 | -0,07914 | 0,963779 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA0868 | SPV_1623, srf-03, comA, comB | 0,74547 | 0,677056 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA | Target | Log2FC | Adjusted P value | Screen | Contrast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sgRNA1362 | SPV_1931 | 4,237775065 | 0,025273781 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA0046 | SPV_0131 | 3,45244365 | 0,000257296 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA0872 | SPV_0010 | 2,89001648 | 1,99841E-06 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA0943 | SPV_0418 | 2,646042226 | 0,01539123 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

| sgRNA0606 | SPV_1594, SPV_1595 | 1,544551591 | 0,041585927 | 1st, wt | Max_vs_Middle |

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

TableS1: sCRilecs-seq results.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75607/elife-75607-supp1-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 2

TableS2: GO enrichment of sCRilecs-seq hits.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75607/elife-75607-supp2-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 3

Table S3: sCRilecs-seq results for mevalonate mutant.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75607/elife-75607-supp3-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 4

Table S4: GO enrichment of sCRilecs-seq hits of mevalonate mutant.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75607/elife-75607-supp4-v2.xlsx

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/75607/elife-75607-transrepform1-v2.docx