Effectiveness of rapid SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing in supporting infection control for hospital-onset COVID-19 infection: Multicentre, prospective study

Figures

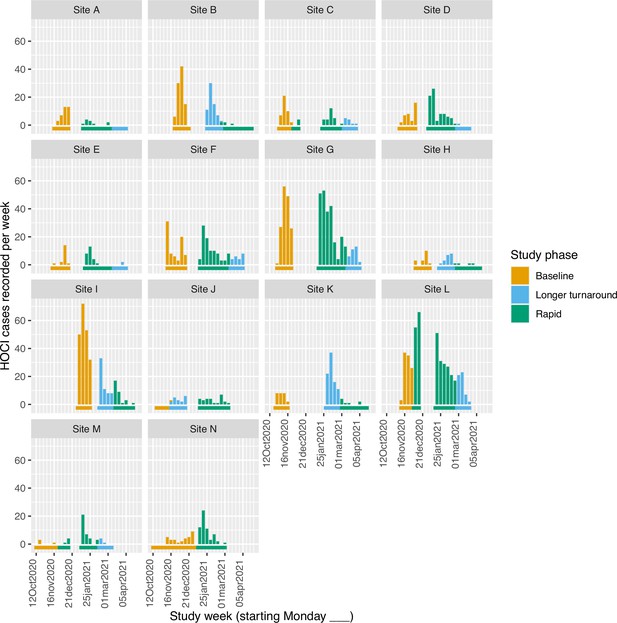

Plots of the median turnaround time against the percentage of hospital-onset COVID-19 infection (HOCI) cases with sequence reporting tool (SRT) reports returned for the rapid (left panel) and longer-turnaround (right panel) sequencing phases across the 14 study sites.

The size of each circle plotted indicates the number of HOCI cases observed within each phase for each site, with letter labels corresponding to study site. The criteria for inclusion in our sensitivity analysis are displayed as the green rectangle in the rapid phase plot, and sites on the longer-turnaround phase plot are colour-coded by their inclusion. In the rapid phase, SRT reports were returned for 0/4 HOCI cases recorded for site H. Site N did not have a longer-turnaround phase, Site A observed 0 HOCI cases, and sites D and E returned SRT reports for 0/1 and 0/2 HOCI cases, respectively, in this phase.

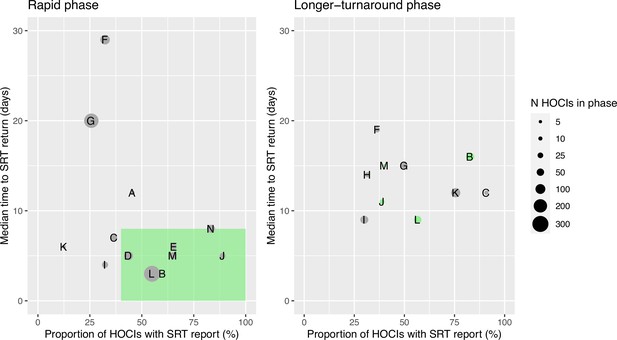

Plots of the proportion of returned sequence reporting tool (SRT) reports that had an impact on infection prevention and control (IPC) actions (a, b) and that were reported to be useful by IPC teams (c, d).

Data are shown for all sites in (a) and (c), and for the seven sites included in the ’per protocol’ sensitivity analysis in (b) and (d). Results are only shown up to turnaround times of ≤28 days, and grouped proportions are shown for ≥9 days because of data sparsity at higher turnaround times. Error bars show binomial 95% CIs. ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ outcomes for individual hospital-onset COVID-19 infection (HOCI) cases are displayed, colour-coded by rapid (red) and longer-turnaround (blue) intervention phases and with random jitter to avoid overplotting. ‘Unsure’ responses were coded as ‘No’ for (c) and (d).

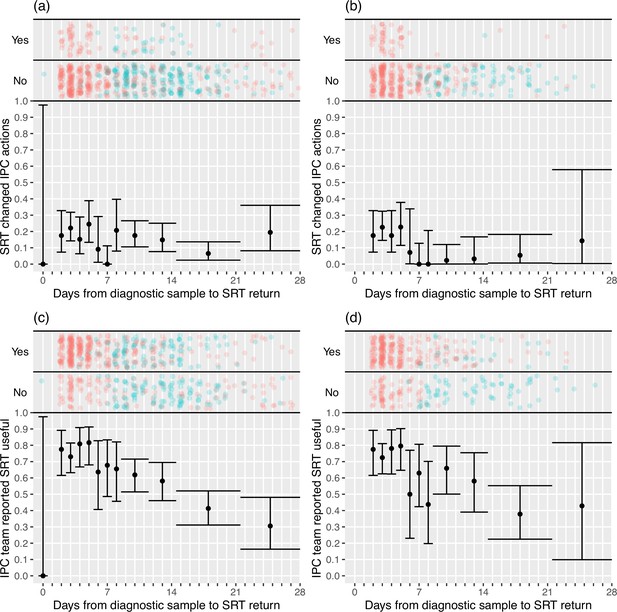

Flow diagram of study site enrolment and intervention implementation.

*Baseline phase extended for one site due to a complete lack of hospital-onset COVID-19 infection (HOCI) cases during the first few weeks of study period and omission of longer-turnaround sequencing phase. †Rapid sequencing phase truncated at one site due to cessation of enrolment at all sites.

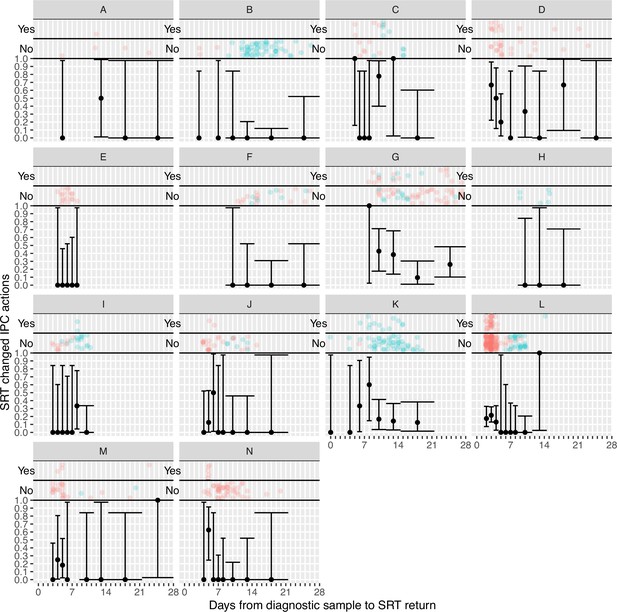

Plots of the proportion of returned sequence reporting tool (SRT) reports that had an impact on infection prevention and control (IPC) actions by study site.

Results are only shown up to turnaround times of ≤28 days, and grouped proportions are shown for ≥9 days because of data sparsity at higher turnaround times. Error bars show binomial 95% CIs. ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ outcomes for individual hospital-onset COVID-19 infection (HOCI) cases are displayed, colour-coded by rapid (red) and longer-turnaround (blue) intervention phases and with random jitter to avoid overplotting.

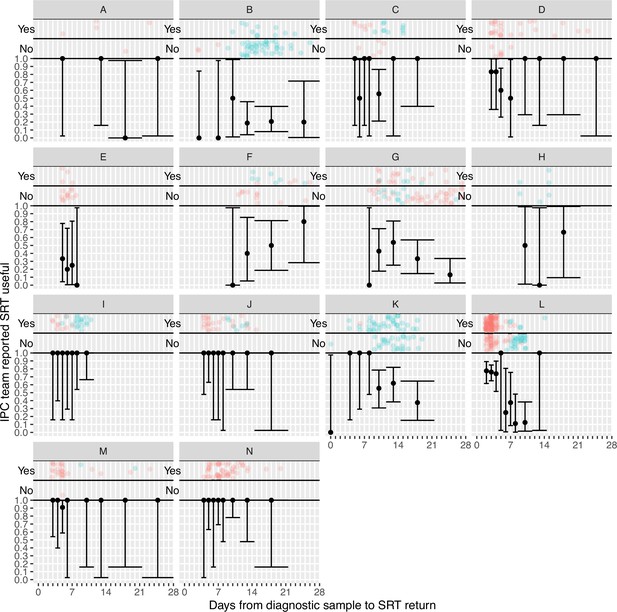

Plots of the proportion of returned sequence reporting tool (SRT) reports that were reported to be useful by infection prevention and control (IPC) teams by study site.

Results are only shown up to turnaround times of ≤28 days, and grouped proportions are shown for ≥9 days because of data sparsity at higher turnaround times. Error bars show binomial 95% CIs. ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ outcomes for individual hospital-onset COVID-19 infection (HOCI) cases are displayed, colour-coded by rapid (red) and longer-turnaround (blue) intervention phases and with random jitter to avoid overplotting. ‘Unsure’ responses were coded as ‘No’.

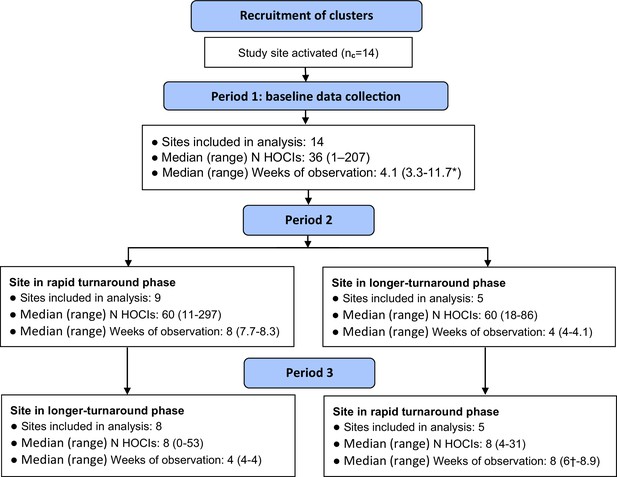

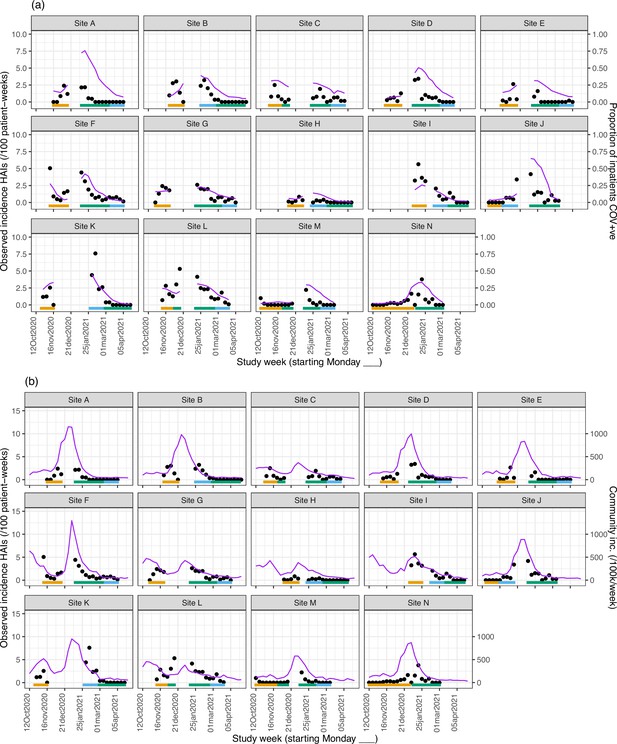

Weekly incidence of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) at each site (●), with (a) proportion of all inpatients SARS-CoV-2+ve and (b) local community incidence of SARS-CoV-2+ve tests also plotted on the y-axis (purple line).

Horizontal bars show the duration of study phases (orange: baseline; blue: longer turnaround; green: rapid).

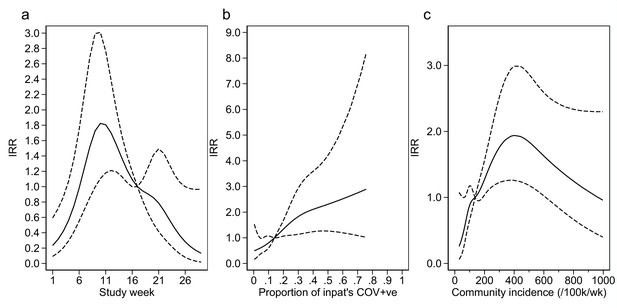

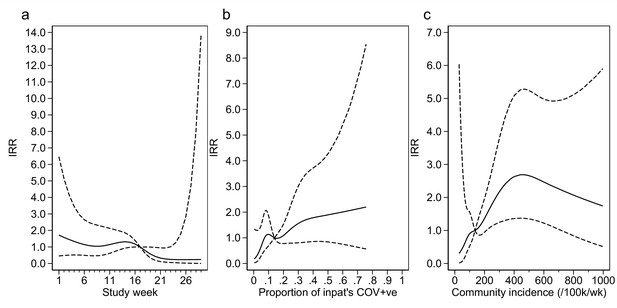

Adustment variables for analysis of weekly incidence of infection prevention and control (IPC)-defined hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) per 100 inpatients, as described in Table 3.

Incidence rate ratios are displayed relative to the median for (a) calendar time expressed as study week from 12 October 2020, (b) proportion of inpatients with positive SARS-CoV-2 test, and (c) local community incidence of SARS-CoV-2 (government surveillance data weighted by total set of postcodes for patients at each site). The spline curves shown are estimated simultaneously within the final analysis model and show how these factors have independent contributions to the prediction of the incidence rate for HAIs. The associations for each covariable indicated by model parameter point estimates are shown as solid lines, with 95% CIs shown as dashed lines. Adjustment for (c) was not pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan (SAP), but adding this variable to the model was associated with a statistically significant improvement in fit (p=0.01). The proportion of community-sampled cases in the region that were found to be the Alpha variant on sequencing was also considered, but adding this as a linear predictor did not lead to a statistically significant improvement in model fit (p=0.78).

Adustment variables for analysis of weekly incidence of infection prevention and control (IPC)-defined outbreak events per 1000 inpatients, as described in Table 3.

Incidence rate ratios are displayed relative to the median for (a) calendar time expressed as study week from 12 October 2020, (b) proportion of inpatients with positive SARS-CoV-2 test, and (c) local community incidence of SARS-CoV-2 (government surveillance data weighted by total set of postcodes for patients at each site). The spline curves shown are estimated simultaneously within the final analysis model and show how these factors have independent contributions to the prediction of the incidence rate for outbreaks. The associations for each covariable indicated by model parameter point estimates are shown as solid lines, with 95% CIs shown as dashed lines. Adjustment for (c) was not pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan (SAP), but adding this variable to the model was associated with a near-statistically significant improvement in fit (p=0.05) and was included for consistency with the analysis of individual hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). The proportion of community-sampled cases in the region that were found to be the Alpha variant on sequencing was also considered, but adding this as a linear predictor did not lead to a statistically significant improvement in model fit (p=0.80).

Tables

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the participants by study phase.

| Characteristic at screening | Study phase | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Longer-turnaround | Rapid | ||

| N HOCI cases | 850 | 373 | 947 | 2170 |

| N HOCI cases per site, median (range); N sites | 36 (1–207); 14 | 19 (0–86); 13 | 30.5 (4-297); 14 | 103.5 (40-451); 14 |

| HAI classification, n (%) | ||||

| Indeterminate (3–7 days) | 362 (42.6) | 166 (44.5) | 371 (39.2) | 899 (41.4) |

| Probable (8–14 days) | 236 (27.8) | 121 (32.4) | 270 (28.5) | 627 (28.9) |

| Definite (>14 days) | 252 (29.6) | 86 (23.1) | 306 (32.3) | 644 (29.7) |

| Age (years), median (IQR, range) | 77.5 (65.4–85.6, 0.4–100.5) | 77.6 (64.6–86.7, 0.7–100.7) | 76.4 (62.6–85.5, 0.6–103.5) | 76.7 (64.4–85.6, 0.4–103.5) |

| Age ≥70 years, n/N (%) | 589/850 (69.3) | 240/373 (64.3) | 598/947 (63.1) | 1427/2170 (65.8) |

| Sex at birth: female, n/N (%) | 457/850 (53.8) | 177/372 (47.6) | 460/947 (48.6) | 1094/2169 (50.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 668 (78.6) | 275 (73.7) | 732 (77.3) | 1675 (77.2) |

| Mixed ethnicity | 9 (1.1) | 6 (1.6) | 8 (0.8) | 23 (1.1) |

| Asian | 46 (5.4) | 26 (7.0) | 34 (3.6) | 106 (4.9) |

| Black Caribbean or African | 36 (4.2) | 18 (4.8) | 46 (4.9) | 100 (4.6) |

| Other | 6 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (0.4) | 11 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 85 (10.0) | 47 (12.6) | 123 (13.0) | 255 (11.8) |

| Symptomatic at time of sampling, n/N (%) | 167/739 (22.6) | 58/322 (18.0) | 106/659 (16.1) | 331/1720 (19.2) |

| Significant comorbidity present, n/N (%) | 650/776 (83.8) | 260/323 (80.5) | 574/757 (75.8) | 1484/1856 (80.0) |

| Pregnant, n/N (%) | 6/451 (1.3) | 1/177 (0.6) | 4/445 (0.9) | 11/1073 (1.0) |

| Hospital admission route, n (%) | ||||

| Emergency department | 605 (71.2) | 258 (69.2) | 549 (58.0) | 1412 (65.1) |

| Hospital transfer | 59 (6.9) | 21 (5.6) | 51 (5.4) | 131 (6.0) |

| Care home | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.1) |

| GP referral | 38 (4.5) | 15 (4.0) | 76 (8.0) | 129 (5.9) |

| Outpatient clinic ref. | 27 (3.2) | 20 (5.4) | 30 (3.2) | 77 (3.5) |

| Other | 42 (4.9) | 9 (2.4) | 48 (5.1) | 99 (4.6) |

| Unknown | 76 (8.9) | 50 (13.4) | 193 (20.4) | 319 (14.7) |

-

GP, general practitioner; HAI, hospital-acquired infection; HOCI, hospital-onset COVID-19 infection.

Per hospital-onset COVID-19 infection (HOCI) implementation and outcome summary by study intervention phase, overall and within the 7/14 sites included in the ’per protocol’ sensitivity analysis.

| All study sites | Sensitivity analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study phase | Total | Study phase | |||

| Longer-turnaround | Rapid | Longer-turnaround | Rapid | ||

| N HOCI cases | 373 | 947 | 1320 | 143 | 533 |

| Implementation | |||||

| Sequence returned within expected timeline, n (%)* | 229 (61.4) | 377 (39.8) | 606 (45.9) | 81 (56.6) | 204 (38.3) |

| Sequence returned within study period, n (%)* | 277 (74.3) | 596 (62.9) | 873 (66.1) | 98 (68.5) | 347 (65.1) |

| SRT report returned within target timeline (10 days for longer-turnaround, 2 days for rapid), n (%) | 79 (21.2) | 44 (4.6) | 123 (9.3) | 35 (24.5) | 44 (8.3) |

| SRT report returned within study period, n (%) | 215 (57.6) | 435 (45.9) | 650 (49.2) | 92 (64.3) | 317 (59.5) |

| Time from sample to report return (days), median (IQR, range) [n] | 13 (9–15, 0–36) [215] | 5 (3-11, 2-84) [430] | 9 (4-14, 0-84) [645] | 13 (9–17, 6–29) [92] | 4 (3-6, 2-64) [312] |

| Sequencing results | |||||

| SRT-suggestive patient acquired infection post-admission, n/N (%) | 196/212 (92.5) | 384/423 (90.8) | 580/635 (91.3) | 85/92 (92.4) | 287/311 (92.3) |

| SRT-suggestive patient is part of ward outbreak, n/N (%) | 151/212 (71.2) | 260/423 (61.5) | 411/635 (64.7) | 65/92 (70.7) | 202/311 (65.0) |

| Linkage identified not suspected at initial IPC investigation: | |||||

| All HOCIs in phase n/N (%†, 95% CI) | 24/348 (6.8, 1.7–11.8) | 46/915 (6.7, 2.0–11.3) | 70/1263 (5.5) | 11/139 (7.9, 3.4–12.4) | 39/512 (7.6, 5.3–9.9) |

| When SRT returned n/N (%) | 24/190 (12.6) | 46/403 (11.4) | 70/593 (11.8) | 11/88 (12.5) | 39/296 (13.2) |

| SRT excluded IPC-identified hospital outbreak, n/N (%) | 14/213 (6.6) | 27/428 (6.3) | 41/641 (6.4) | 9/92 (9.8) | 25/310 (8.1) |

| Impact on IPC | |||||

| SRT changed IPC practice: | |||||

| All HOCIs in phase n/N (%†, 95% CI) | 25/373 (7.4, 1.1–13.6) | 74/941 (7.8, 2.4–13.2) | 99/1314 (7.5) | 1/143 (0.7, 0.0–2.1) | 52/527 (9.9, 7.3–12.4) |

| When SRT returned n/N (%) | 25/215 (11.6) | 74/429 (17.2) | 99/644 (15.4) | 1/92 (1.1) | 52/311 (16.7) |

| SRT changed IPC practice for ward, n/N (%) | 13/215 (6.0) | 31/429 (7.2) | 44/644 (6.8) | 0/92 (0.0) | 28/311 (9.0) |

| SRT used in IPC decisions beyond ward, n/N (%) | 12/215 (5.6) | 45/428 (10.5) | 57/643 (8.9) | 1/92 (1.1) | 27/310 (8.7) |

| IPC team reported SRT to be useful, n/N (%) | |||||

| Yes | 107/215 (49.8) | 303/428 (70.8) | 410/643 (63.8) | 25/92 (27.2) | 245/310 (79.0) |

| No | 67/215 (31.2) | 71/428 (16.6) | 138/643 (21.5) | 50/92 (54.3) | 57/310 (18.4) |

| Unsure | 41/215 (19.1) | 54/428 (12.6) | 95/643 (14.8) | 17/92 (18.5) | 8/310 (2.6) |

| HCW absence on ward | |||||

| Proportion of HCWs on sick leave due to COVID-19, median (IQR, range) [n] | 0.09 (0.00–0.15, 0.00–0.30) [49] | 0.13 (0.07–0.29, 0.00–1.00) [162] | 0.13 (0.04–0.27, 0.00–1.00) [321] ‡ | 0.09 (0.00–0.15, 0.00–0.30) [49] | 0.13 (0.08–0.29, 0.00–1.00) [143] |

-

HCW, healthcare worker; HOCI, hospital-onset COVID-19 infection; IPC, infection prevention and control; IQR, interquartile range; SRT, sequence reporting tool.

-

*

As recorded by site, not based on recorded date or availability on central CLIMB server.

-

†

Estimated marginal value from mixed effects model, not raw %, evaluated on intention-to-treat basis with lack of SRT report classified as ‘no’.

-

‡

Includes data for baseline phase: 0.13 (0.00–0.30, 0.00–0.88) [110].

Incidence outcomes by study intervention phase, overall and within the 7/14 sites included in the ’per protocol’ sensitivity analysis.

| Study phase | IRR† (95% CI, p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Longer-turnaround | Rapid | Longer-turnaround vs. baseline | Rapid vs. baseline | |

| All sites | |||||

| n HOCI cases | 850 | 373 | 947 | – | – |

| n IPC-defined HAIs | 488 | 207 | 576 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC-defined HAIs per 100 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* [primary outcome] | 1.0 (0.5, 0.0–1.4, 0.0–5.6) | 0.7 (0.3, 0.0–0.7, 0.0–7.6) ‡ | 0.6 (0.3, 0.0–0.8, 0.0–5.3) ‡ | 1.60 (0.85–3.01; 0.14) | 0.85 (0.48–1.50; 0.54) |

| n IPC-defined outbreak events | 129 | 33 | 114 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC-defined outbreak events per 1000 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* | 2.7 (1.1, 0.0–4.1, 0.0–23.0) | 0.8 (0.0, 0.0–1.0, 0.0–8.9) ‡ | 0.7 (0.0, 0.0–0.0, 0.0–8.9) ‡ | 1.09 (0.38–3.16; 0.86) | 0.58 (0.24–1.39; 0.20) |

| n IPC + sequencing-defined outbreak events | – | 40 | 133 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC + sequencing-defined outbreak events per 1000 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* | – | 1.1 (0.0, 0.0–1.5, 0.0–13.4) ‡ | 0.9 (0.0, 0.0–1.4, 0.0–7.6) ‡ | – | – |

| Sensitivity analysis | |||||

| n HOCI cases | 290 | 143 | 533 | – | – |

| n IPC-defined HAIs | 179 | 91 | 337 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC-defined HAIs per 100 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* [primary outcome] | 0.3 (0.0, 0.0–0.3, 0.0–3.0) | 0.3 (0.0, 0.0–0.0, 0.0–3.4) ‡ | 0.4 (0.0, 0.0–0.3, 0.0–5.3) ‡ | 2.21 (0.82–5.92; 0.10) | 1.75 (0.75–4.08; 0.16) |

| n IPC-defined outbreak events | 58 | 14 | 55 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC-defined outbreak events per 1000 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* | 1.1 (0.0, 0.0–1.3, 0.0–12.9) | 0.3 (0.0, 0.0–0.0, 0.0–5.7) ‡ | 0.4 (0.0, 0.0–0.0, 0.0–8.9) ‡ | 0.83 (0.14–4.93; 0.80) | 0.46 (0.11–1.86; 0.21) |

| n IPC + sequencing-defined outbreak events | – | 14 | 67 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC + sequencing-defined outbreak events per 1000 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* | – | 0.3 (0.0, 0.0–0.0, 0.0–5.7) ‡ | 0.5 (0.0, 0.0–0.0, 0.0–7.6) ‡ | – | – |

-

IPC-defined HAIs are considered to be ‘probable’ or ‘definite’ HAIs.

-

HAI, hospital-acquired infection; HOCI, hospital-onset COVID-19 infection; IPC, infection prevention and control; IQR, interquartile range; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

-

*

Descriptive data over all week-long periods at all study sites.

-

†

Adjusted for proportion of current inpatients at site that are COVID-19 cases, community incidence rate, and calendar time (as displayed in Appendix 1—figure 5 and Appendix 1—figure 6 for all sites).

-

‡

Not including data from the first week of each intervention period or in the week following any break in the intervention period.

Per outbreak event outcomes by study intervention phase.

| Study phase | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Longer-turnaround | Rapid | ||

| IPC-defined outbreak events | ||||

| n outbreak events | 129 | 33 | 114 | 276 |

| n/N (%) of HOCI cases part of outbreak event | 682/850 (80.2) | 314/373 (84.2) | 763/947 (80.6) | 1759/2170 (81.1) |

| Number of HOCIs per outbreak event, median (IQR, range) | 5.0 (3–8, 2–43) | 5.0 (3–9, 2–24) | 4.0 (2–7, 2–31) | 4.0 (2–8, 2–43) |

| Proportion of HCWs on sick leave due to COVID-19, median (IQR, range) [n] | 0.13 (0.00–0.35, 0.00–0.50) [13] | 0.05 (0.00–0.18, 0.00–0.30) [7] | 0.20 (0.08–0.33, 0.00–0.89) [14] | 0.13 (0.00–0.31, 0.00–0.89) [34] |

| IPC + sequencing-defined outbreak events | ||||

| n outbreak events | – | 41 | 135 | 176 |

| n/N (%) of HOCI cases part of outbreak event | – | 292/373 (78.3) | 705/947 (74.4) | 997/1320 (75.5) |

| Number of HOCIs per outbreak event, median (IQR, range) | – | 5.0 (2-8, 2-23) | 3.0 (2-6, 2-29) | 3.0 (2-7, 2-29) |

| For first HOCI in outbreak: | ||||

| SRT changed IPC practice, n/N (%, 95% CI) | – | 4/41 (10.4, 0–21.0) | 19/133 (14.9, 6.6–23.2) | 23/174 (13.2) |

| SRT changed IPC practice for ward, n/N (%) | – | 2/35 (5.7) | 6/82 (7.3) | 8/117 (6.8) |

| SRT used in IPC decisions beyond ward, n/N (%) | – | 2/35 (5.7) | 10/82 (12.2) | 12/117 (10.3) |

| IPC team reported SRT to be useful, n/N (%) | ||||

| Yes | – | 20/35 (57.1) | 51/82 (62.2) | 71/117 (60.7) |

| No | – | 9/35 (25.7) | 15/82 (18.3) | 24/117 (20.5) |

| Unsure | – | 6/35 (17.1) | 16/82 (19.5) | 22/117 (18.8) |

| SRT would ideally have changed IPC practice, n/N (%*, 95% CI) | – | 4/41 (9.8) | 19/133 (14.3) | 23/174 (13.2) |

-

Odds ratio of SRT changed IPC practice for ‘rapid vs. longer-turnaround’ phases 1.54 (95% CI 0.37–6.44; p=0.52).

-

HCW, healthcare worker; HOCI, hospital-onset COVID-19 infection; IPC, infection prevention and control; IQR, interquartile range; SRT, sequence reporting tool.

-

*

Estimated marginal value from mixed effects model, not raw %, evaluated on intention-to-treat basis with lack of SRT report classified as ‘No’.

Descriptive summary of impact of sequencing on IPC actions implemented during study intervention phases, as recorded on pre-specified study reporting forms.

| Study phase | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longer-turnaround sequencing | Rapid turnaround sequencing | |||||

| N HOCI cases | 373 | 947 | ||||

| Review of IPC actions already taken | Support | Refute | Missing | Support | Refute | Missing |

| SRT results support or refute IPC actions already taken* | 200/213 (93.9) | 7/213 (3.3) | 2 | 389/428 (90.9) | 9/428 (2.1) | 7 |

| Changes to IPC practice following SRT | To enhanced | To routine | No change | To enhanced | To routine | No change |

| Change to cleaning protocols on ward | 2/185 (1.1) | 0/185 (0.0) | 183/185 (98.9) | 7/341 (2.1) | 0/341 (0.0) | 334/341 (97.9) |

| To greater | To fewer | No change | To greater | To fewer | No change | |

| Change to visitor restrictions | 1/186 (0.5) | 0/186 (0.0) | 185/186 (99.5) | 1/340 (0.3) | 0/340 (0.0) | 339/340 (99.7) |

| To ‘cohort nursing’ | To ‘other restrictions’ | No change | To ‘cohort nursing’ | To ‘other restrictions’ | No change | |

| Change to staffing restrictions on ward | 0/186 (0.0) | 1/186 (0.5) | 185/186 (99.5) | 0/336 (0.0) | 1/336 (0.3) | 335/336 (99.7) |

| Increase | Decrease | No change | Increase | Decrease | No change | |

| Hand hygiene audit frequency | 1/185 (0.5) | 0/185 (0.0) | 184/185 (99.5) | 10/335 (3.0) | 0/335 (0.0) | 325/335 (97.0) |

| IPC staff visits to ward | 1/185 (0.5) | 0/185 (0.0) | 184/185 (99.5) | 14/335 (4.2) | 0/335 (0.0) | 321/335 (95.8) |

| Assessment of alcogel stocks | 0/185 (0.0) | 0/185 (0.0) | 185/185 (100.0) | 2/335 (0.6) | 0/335 (0.0) | 333/335 (99.4) |

| Assessment of soap stocks | 0/185 (0.0) | 0/185 (0.0) | 185/185 (100.0) | 2/334 (0.6) | 0/334 (0.0) | 332/334 (99.4) |

| Assessment of aseptic non-touch technique compliance | 0/185 (0.0) | 0/185 (0.0) | 185/185 (100.0) | 8/335 (2.4) | 0/335 (0.0) | 327/335 (97.6) |

| Assessment of PPE supply | 1/185 (0.5) | 0/185 (0.0) | 184/185 (99.5) | 9/336 (2.7) | 0/336 (0.0) | 327/336 (97.3) |

| Availability of doffing and donning buddy | 0/185 (0.0) | 0/185 (0.0) | 185/185 (100.0) | 1/333 (0.3) | 0/333 (0.0) | 332/333 (99.7) |

| IPC signage assessment | 1/185 (0.5) | 0/185 (0.0) | 184/185 (99.5) | 12/336 (3.6) | 0/336 (0.0) | 324/336 (96.4) |

| IPC signage implementation | 1/185 (0.5) | 0/185 (0.0) | 184/185 (99.5) | 11/336 (3.3) | 0/336 (0.0) | 325/336 (96.7) |

| Training on IPC procedures | 0/185 (0.0) | 0/185 (0.0) | 185/185 (100.0) | 8/336 (2.4) | 0/336 (0.0) | 328/336 (97.6) |

-

Data shown as n or n/N (%). Overall impact on IPC actions per HOCI case is given in Table 2.

-

HOCI, hospital-onset COVID-19 infection; IPC, infection prevention and control; PPE, personal protective equipment; SRT, sequence reporting tool.

-

*

Sites could select ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ for both ‘Support’ and ‘Refute’ as these were entered as separate data items.

Descriptive summary of impact of sequencing on IPC actions implemented during study intervention phases, only including the first HOCI in each IPC+sequencing-defined outbreak event, as recorded on pre-specified study reporting forms.

| Study phase | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longer-turnaround sequencing | Rapid turnaround sequencing | |||||

| N HOCI cases | 41 | 135 | ||||

| Review of IPC actions already taken | Support | Refute | Missing | Support | Refute | Missing |

| SRT results support or refute IPC actions already taken* | 30/35 (85.7) | 3/35 (8.6) | 0 | 71/82 (86.6) | 5/82 (6.1) | 2 |

| Changes to IPC practice following SRT | To enhanced | To routine | No change | To enhanced | To routine | No change |

| Change to cleaning protocols on ward | 1/34 (2.9) | 0/34 (0.0) | 33/34 (97.1) | 1/70 (1.4) | 0/70 (0.0) | 69/70 (98.6) |

| To greater | To fewer | No change | To greater | To fewer | No change | |

| Change to visitor restrictions | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 1/70 (1.4) | 0/70 (0.0) | 69/70 (98.6) |

| To ‘cohort nursing’ | To ‘other restrictions’ | No change | To ‘cohort nursing’ | To ‘other restrictions’ | No change | |

| Change to staffing restrictions on ward | 0/34 (0.0) | 1/34 (2.9) | 33/34 (97.1) | 0/70 (0.0) | 1/70 (1.4) | 69/70 (98.6) |

| Increase | Decrease | No change | Increase | Decrease | No change | |

| Hand hygiene audit frequency | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 3/70 (4.3) | 0/70 (0.0) | 67/70 (95.7) |

| IPC staff visits to ward | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 5/70 (7.1) | 0/70 (0.0) | 65/70 (92.9) |

| Assessment of alcogel stocks | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 2/70 (2.9) | 0/70 (0.0) | 68/70 (97.1) |

| Assessment of soap stocks | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 2/70 (2.9) | 0/70 (0.0) | 68/70 (97.1) |

| Assessment of aseptic non-touch technique compliance | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 3/70 (4.3) | 0/70 (0.0) | 67/70 (95.7) |

| Assessment of PPE supply | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 3/70 (4.3) | 0/70 (0.0) | 67/70 (95.7) |

| Availability of doffing and donning buddy | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 1/70 (1.4) | 0/70 (0.0) | 69/70 (98.6) |

| IPC signage assessment | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 4/70 (5.7) | 0/70 (0.0) | 66/70 (94.3) |

| IPC signage implementation | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 4/70 (5.7) | 0/70 (0.0) | 66/70 (94.3) |

| Training on IPC procedures | 0/34 (0.0) | 0/34 (0.0) | 34/34 (100.0) | 4/70 (5.7) | 0/70 (0.0) | 66/70 (94.3) |

-

Data shown as n or n/N (%). Overall impact on IPC actions per HOCI case is given in Appendix 1—table 1.

-

HOCI, hospital-onset COVID-19 infection; IPC, infection prevention and control; PPE, personal protective equipment; SRT, sequence reporting tool.

-

*

Sites could select ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ for both ‘Support’ and ‘Refute’ as these were entered as separate data items.

Per-sample costs of SARS-CoV-2 genome rapid and longer-turnaround sequencing.

| Laboratories | Lab 1 | Lab 2 | Lab 3 | Lab 4 | Lab 5 | Lab 6 | Lab 7 | Lab 8 | Lab 9 | Lab 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid turnaround sequencing | |||||||||||

| Sequencing platform | Illumina MiSeq | Nanopore MinION/ GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore MinION/ GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Illumina MiSeq | Illumina MiSeq | Mean |

| Batch size | 24 | 24 | 24 | 96 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 96 | 96 | |

| Equipment | £45.11 | £26.06 | £19.34 | £4.38 | £12.38 | £24.66 | £11.99 | £11.26 | £5.91 | £6.13 | £16.72 |

| Consumables | £69.14 | £54.56 | £87.07 | £31.11 | £79.06 | £28.84 | £62.09 | £46.02 | £14.37 | £39.63 | £51.19 |

| Staff | £6.11 | £20.25 | £24.66 | £7.93 | £11.16 | £5.66 | £12.16 | £8.45 | £2.20 | £3.45 | £10.20 |

| Total per-sample cost | £120.36 | £100.87 | £131.07 | £43.43 | £102.60 | £59.17 | £86.23 | £65.73 | £22.48 | £49.21 | £78.11 |

| Total cost (including overheads calculated at 20%) | £144.43 | £121.04 | £157.28 | £52.11 | £123.12 | £71.01 | £103.48 | £78.88 | £26.97 | £59.05 | £93.74 |

| Longer-turnaround sequencing | |||||||||||

| Sequencing platform | Illumina MiSeq | Nanopore MinION/ GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore MinION/ GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore GridiON | Nanopore MinION | Illumina MiSeq | Mean |

| Batch size | 24 | 24 | 24 | 96 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 96 | 24 | 96 | |

| Equipment | £40.60 | £22.15 | £17.02 | £3.94 | £11.88 | £22.44 | £11.27 | £2.81 | £2.54 | £5.76 | £14.04 |

| Consumables | £61.53 | £48.56 | £77.49 | £27.69 | £70.36 | £25.67 | £55.26 | £11.51 | £33.75 | £35.27 | £44.71 |

| Staff | £4.95 | £15.19 | £16.52 | £2.78 | £2.23 | £4.53 | £12.04 | £8.45 | £11.85 | £3.32 | £8.19 |

| Total per-sample cost | £107.08 | £85.89 | £111.03 | £34.41 | £84.48 | £52.65 | £78.56 | £22.77 | £48.13 | £44.34 | £66.94 |

| Total cost (including overheads calculated at 20%) | £128.50 | £103.07 | £133.24 | £41.29 | £101.38 | £63.18 | £94.28 | £27.33 | £57.76 | £53.21 | £80.32 |

Incidence outcomes by study intervention phase with unadjusted IRR.

| Study phase | IRR† (95% CI, p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Longer-turnaround | Rapid | Longer-turnaround vs. baseline | Rapid vs. baseline | |

| All sites | |||||

| n HOCI cases | 850 | 373 | 947 | – | – |

| n IPC-defined HAIs | 488 | 207 | 576 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC-defined HAIs per 100 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* [primary outcome] | 1.0 (0.5, 0.0–1.4, 0.0–5.6) | 0.7 (0.3, 0.0–0.7, 0.0–7.6) ‡ | 0.6 (0.3, 0.0–0.8, 0.0–5.3) ‡ | 0.49 (0.21–1.19, 0.12) | 0.47 (0.21–1.08, 0.07) |

| n IPC-defined outbreak events | 129 | 33 | 114 | – | – |

| Weekly incidence of IPC-defined outbreak events per 100 inpatients, mean (median, IQR, range)* | 0.3 (0.1, 0.0–0.4, 0.0–2.3) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.0–0.1, 0.0–0.9) ‡ | 0.1 (0.0, 0.0–0.0, 0.0–0.9) ‡ | 0.25 (0.10–0.66, 0.005) | 0.23 (0.10–0.54, 0.001) |

-

IPC-defined HAIs are considered to be ‘probable’ or ‘definite’ HAIs.

-

HAI, hospital-acquired infection; HOCI, hospital-onset COVID-19 infection; IPC, infection prevention and control; IQR, interquartile range; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

-

*

Descriptive data over all week-long periods at all study sites.

-

†

Without adjustment for proportion of current inpatients at site that are COVID-19 cases, community incidence rate, and calendar time.

-

‡

Not including data from the first week of each intervention period, or in the week following any break in the intervention period.

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

List of COG-UK HOCI investigators.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78427/elife-78427-supp1-v2.docx

-

Supplementary file 2

Member list for the COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78427/elife-78427-supp2-v2.docx

-

MDAR checklist

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/78427/elife-78427-mdarchecklist1-v2.docx