Equity, Diversity and Inclusion: A guide for writing anti-racist tenure and promotion letters

Abstract

In a two-page tenure letter, senior faculty can make or break a career. This power has an outsized impact on Black academics and other scholars with marginalized identities, who are awarded tenure at lower rates than their white colleagues. We suggest that this difference in tenure rates is due to an implicit, overly narrow definition of academic excellence that does not recognize all the contributions that Black scholars make to their departments, institutions and academia in general. These unrecognized contributions include the (often invisible) burdens of mentoring and representation that these scholars bear disproportionately. Here we propose a set of practical steps for writing inclusive, anti-racist tenure letters, including what to do before writing the letter, what to include (and not include) in the letter itself, and what to do after writing the letter to further support the candidate seeking tenure. We are a group of mostly non-Black academics in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) based in the United States who are learning about and working toward Black liberation in academia; we hope these recommendations will help ongoing efforts to move toward an inclusive academia that appreciates and rewards diverse ways of doing, learning and knowing.

Introduction

Senior faculty can make, shape, and – unfortunately – break the careers of junior faculty, especially within the tenure review process. Black scholars, already severely underrepresented as junior faculty, are promoted with tenure at a lower rate than their white colleagues (Frazier, 2011; Herbert, 2012; Stewart, 2012; US Department of Education, 2017). And not because they are not as ‘good’. If anything, Black scholars have had to overcome more hurdles than their white colleagues to become assistant professors (Diep, 2020; Frazier, 2011), surviving and excelling in long and unforgiving training and selection processes that are biased against them. Why, then, are they not being promoted?

We believe this is primarily due to two factors that tenure letter writers can intentionally work to overturn: (i) a narrow definition of ‘excellence’ that encompasses only some forms of contribution to academia, and (ii) the unrecognized invisible burdens of mentoring and representation that fall disproportionately on the shoulders of Black faculty (and more so on Black women, who hold doubly marginalized, intersectional identities).

Here we put forth a set of recommendations for writing inclusive, anti-racist, tenure letters that allow letter-writers to counteract these two factors by adopting an expansive view of how scholars contribute to academia, and by promoting the academic culture we all want to support. Throughout, we will refer specifically to Black faculty, as we are writing from a US-centric vantage point on academia, where anti-Black racism imposes myriad, interacting harms on Black scholars (Bell et al., 2021). However, the issues we discuss and recommendations we make apply to indigenous scholars, scholars of Color, LGBTQ+ scholars, scholars with disabilities, first-generation scholars, scholars from low-income backgrounds, and, in most academic fields, also women. We emphasize that our recommendations by no means ‘lower the bar’ of tenure standards in academia. To the contrary, recognizing the full ways that historically excluded scholars excel and help create an excellent academic culture can help raise the standards across academia.

Academia and ‘white supremacy culture’

The academic profession was developed to have strict boundaries about who is allowed to be a part of the profession and what work is valued. Certain values and qualities (such as objectivity, linearity, generalizability, and detachment) have long been the standard for evaluating academic rigor and granting membership into this highly selective profession (Gonzales, 2018). Thus, Black scholars engaging in community-focused research and racial justice work are often evaluated negatively because their work is viewed as not being objective and their advocacy is viewed as problematic (Gonzales, 2018). Indeed, Black scholars are overrepresented in topics related to racial discrimination and African studies, but often cited less than scholars from other groups (Kozlowski et al., 2022). Therefore, in evaluation processes, like tenure and promotion, their research is often undervalued by evaluators embedded in what Dr. Tema Okun describes as ‘white supremacy culture’ (Okun, 1999; Okun, 2021).

According to Okun, “White supremacy culture is the widespread ideology baked into the beliefs, values, norms, and standards of our groups (many if not most of them), our communities, our towns, our states, our nation, teaching us both overtly and covertly that whiteness holds value, whiteness is value” (https://www.whitesupremacyculture.info/what-is-it.html). Whether we are aware of it or not, academic culture is steeped in the beliefs and values Okun associates with ‘white supremacy culture’, including:

Perfectionism: the belief that there is ‘one right way’ to do things and a false sense that we can be objective, and that mistakes are personal.

Quantity over quality: valuing things that can be measured – publications, grant money – more highly than processes that are harder to quantify (e.g., mentoring relationships, morale).

Individualism: de-emphasis of team-work and collaboration and over-emphasis on individual achievement and competition.

Defensiveness: a tendency to protect current systems of power at the expense of hearing new ideas; perceiving criticisms as threats.

Sense of urgency: an imposed sense of urgency makes it difficult to take time to be inclusive and to reflect on and learn from mistakes, and draws attention away from truly urgent work for racial justice regardless of academic field.

These values are not a necessity in academia. Most of us, having been trained in this culture for years, may not even recognize these invisible but ever-present ‘rules of the game’ despite the fact that these rules limit creativity and inclusion. Naming these values as ones we have adopted makes clear that they are not axioms of academic culture. There are alternatives. Those of us committed to disrupting this implicit and harmful culture have a right and obligation to actively promote an academic community that recognizes and benefits from the expertise of all people who participate in academia. One way to accomplish this on an individual level is to reconsider how we write letters of assessment, including tenure and promotion letters, so that they embody the cultural shift we'd like to see.

What are anti-racist tenure and promotion letters?

Anti-racist tenure and promotion letters provide an avenue of intervention and advocacy to challenge the exclusionary and harmful aspects of academia. In evaluating scholarship that does not necessarily conform to ‘white supremacy culture’ values, we must recognize that our personal biases influence both our scientific practice and our tendency to uphold these values of scientific pursuit. If we are to move beyond these exclusionary practices, we must recognize these biases in all of our academic practices and value other knowledge systems beyond that of the ‘traditional’ epistemology of science.

Academia’s embodiment of ‘white supremacy culture’ diminishes the learning environment in our institutions, limits vital representation of Black scholars and their scholarship, and harms Black faculty wellness and opportunities for advancement (Davis, 2021; Diep, 2020; Mosley et al., 2021; Bell et al., 2021). These harms pervade all aspects of academia and are particularly well-documented for the tenure and promotion process (Frazier, 2011; Jones et al., 2015), where examples include lack of recognition for increased service load (Gewin, 2020; Guarino and Borden, 2017; Hirshfield and Joseph, 2012; Jimenez et al., 2019; McCluney and Rabelo, 2019; Moore, 2017, Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, 2017), marginalization of research (Padilla, 1994; Settles et al., 2022), and lower rates of publication and funding (Taffe and Gilpin, 2021).

While critical reforms have been identified (e.g., Roadmap for Racial Equity at UNC Chapel Hill) and some institutions – such as, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and University of Oregon – are pursuing structural remedies to some of these problems (Truong, 2021), many scholars who wish to support anti-racist reforms of academia are unable to individually effect such changes in their institutions. Indeed, even scholars who have successfully navigated the tenure process and hold relatively powerful positions in their institutions and disciplines likely still lack the power to change the policies and procedures that harm Black scholars. However, such successful scholars are regularly asked to serve as external evaluators in the tenure process at peer institutions; and it is in this process that individual scholars committed to anti-racism and to an expansive and inclusive academic culture can have a substantial impact on the career trajectories of Black scholars.

Writing tenure/promotion letters is an excellent opportunity to push back against traditional, narrow criteria for promotion and toward a more holistic view of scholarly contributions (for example, see Renwick et al., 2020). Although previous guidelines for writing tenure and promotion letters have been proposed (Goldman, 2016; Goldman, 2017; Kong et al., 2021; Strassman, 2016; Female Science Professor, 2014), they often embrace and perpetuate an academic culture focused on a traditional, narrow understanding of scholarship. Writing a tenure letter purely from one’s own lived experience and expectations can also inadvertently introduce bias and undermine the success of the candidate, as most letter writers have not experienced academia as a racially marginalized scholar.

The current system is a vicious positive feedback cycle: letters written by the majority of faculty (i.e., based on the tacitly accepted values of white men) reify the current culture and squander the opportunity to intentionally recognize its limitations and expand beyond it. The goal of the guidelines below is to bring into the tenure and promotion process a holistic, inclusive, and equitable understanding of what successful scholarship can look like and who can be a successful scholar. We intend to broaden recommenders’ critical awareness of the scope of scholarship and scholarly activities that are often unrecognized and that fall disproportionately on the shoulders of Black scholars. And we encourage recommenders to frame and describe such work for all tenure/promotion candidates, not only Black or other marginalized candidates, so as to align our evaluation criteria with our stated values.

Authors’ positionality statement

To allow readers to best contextualize our recommendations, we would like to explicitly acknowledge our positionality and limitations in putting together the below recommendations. We are a group of mostly non-Black academics in STEM fields, most of us women, who are learning about and working toward Black liberation in academia. We participated in the 2020 and 2021 “Academics for Black Survival and Wellness (A4BL)” courses envisioned and implemented by Dr. Della Mosley and Pearis Bellamy, with shared wisdom from a large number of anti-Black-racism scholars. This set of recommendations arose from a working group formed during the 2021 course.

We recognize that our project represents an incremental challenge to a system in urgent need of major transformations regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion. When contemplating how we could work toward creating a just, equitable, inclusive, and diverse academia, we recognized many limits to our individual and collective knowledge, experiences, and power. This recognition motivated our interest in identifying areas where a single person has an outsized impact on the career trajectory of Black scholars. We therefore offer these recommendations that are based on what we learned from the above coursework, literature on racial and gender bias and equity, and our experiences as largely tenured faculty who are regularly in a position to evaluate fellow scholars.

These recommendations are inspired by the work of Bell et al., 2021, Berhe and Kim, 2019a; Berhe and Kim, 2019b, The University of Arizona Commission on the Status of Women, 2016, Okun, 2021 and Itchuaqiyaq and Walton, 2021. This project is for all academics who are in the position to evaluate Black scholars, and we recommend applying this rubric to letters written on behalf of any scholar in academia.

Practical recommendations for writing anti-racist tenure and promotion letters

Itchuaqiyaq and Walton, 2021 rightly point out that the “act of being called to review is also a call to power”. This is doubly true for tenure review letters, and with that power comes a responsibility to hold both oneself and other power-holders (e.g., letter requesters, evaluation committees) accountable for anti-Black racism and to support the success of marginalized scholars. Here, we provide recommendations for non-Black academics writing letters for Black candidates; however, we believe that these recommendations apply more widely, both to other marginalized scholars and to letter writers of all identities. Based on Okun, 2021 antidotes to ‘white supremacy culture’, we provide the following: (1) preparatory steps before writing a letter, (2) recommendations for writing a letter that recognizes Black excellence and contextualizes achievements within current academic culture, and (3) suggestions for what to do afterward to promote the voices of Black scholars and disrupt anti-Black racism in academia.

The list of recommendations incorporates feedback and reflects substantial contributions from other attendees and leaders of the 2021 Academics for Black Survival and Wellness training and from a diverse group of scholars in our professional networks. We emphasize that these recommendations for critical awareness and intentionality are important even when requested only to evaluate a candidate’s scholarship, and are especially important the more marginalized intersecting identities the candidate holds.

Before writing the letter

First, we encourage you to reflect on your various identities and background, including gender, race, class, sexual orientation, able-bodiedness, culture, ethnicity, religion and nationality. Reflect on both your privileged and marginalized statuses, and use this reflection both to set clear intentions for your letter and to gain a more holistic view on how your identities may impact your letter and your ability to evaluate different aspects of the candidate’s dossier. If you are a white scholar writing a letter for a Black scholar, consider your own racial identity development (see Helms, 2020) and engage with scaffolded anti-racist resources as needed (Stamborski et al., 2020). In what ways does your identity align with the letter readers? In what way does your identity align with the subject of your letter? Why were you asked to write the letter? Clarify your positionality for yourself – what lens do you bring to this evaluation and how do your own identities and backgrounds shape your evaluative process? (See also: Itchuaqiyaq and Walton, 2021; Clemons, 2019; UCLA Library, 2021a; UCLA Library, 2021b; Taylor Institute, 2022; Derry, 2017; Darwin Holmes, 2020 Lacy, 2017).

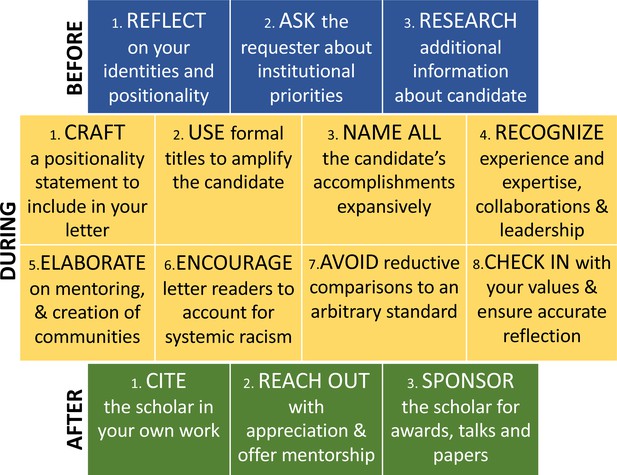

Second, in order to gather relevant information and to encourage reflection on the part of the institution you are writing for, ask the person who requested the letter (e.g., the department chair) about the make-up and perspective of the department and institution (Figure 1 top, box 2). How do they value and weigh research, teaching, and service? What are the faculty and student demographics? How do they account for, support, and evaluate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) work? (See, for example, University of California, Berkeley’s Rubric for Assessing Candidate Contributions to Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging). How do they account for collaborative, ongoing, or community-facing endeavors? Ask for any additional information the person who requested the letter can supply about the candidate so that the candidate’s often invisible and likely uncompensated DEI work can be included in your letter. If the institution or department does not explicitly value such scholarship and/or DEI work, consider how to frame such accomplishments within the institution’s evaluation criteria.

Recommendations for writing anti-racist tenure and promotion letters.

A set of guidelines for what to do before writing the letter (blue boxes), what to include and not include in the letter itself (yellow boxes), and what to do after writing the letter to further support the candidate (green boxes).

As a final preparatory step (Figure 1 top, box 3), research the candidate’s CV, professional website, and public-facing social media to learn more about their influential work inside and outside of academia (e.g., DEI work, collaborative work, leadership). Consider the multiple ways that a research area has been impacted by the presence and contributions of the scholar and how to communicate the importance of work that is not traditionally valued by academia. It may be helpful to familiarize yourself with the embedded values of academia, through reading Okun, 2021 or the work of Dr. Leslie Gonzales (e.g., Gonzales and Waugaman, 2016; Gonzales and Núñez, 2014), in order to recognize the limitations of traditional scholarship as the only currency of contribution to academia. This critical awareness will enable you to write a letter that speaks to those values while challenging tenure and promotion committees to expand their review beyond those values. It may be useful to follow discussions and groups on social media that are outside your immediate community, especially those that include scholars with identities other than your own. This can help to expand your understanding of what is valuable in academia and the hurdles Black scholars may face, and provide you with ideas on how to communicate this new knowledge to others.

When writing the letter

Like we did in this paper, we suggest you include a positionality statement (see Clemons, 2019; UCLA Library, 2021a; UCLA Library, 2021b; Taylor Institute, 2022; Derry, 2017; Darwin Holmes, 2020; Lacy, 2017) or other description of your own backgrounds and experiences and how they shape how you are evaluating the candidate (Figure 1 middle, box 1). It is typical to include a description of one’s academic credentials, but we suggest you also be explicit in sharing the values you hold, as well as other identity factors that may influence your evaluation. Throughout, we recommend you use “I” statements that clarify the subjectivity of your assessments. While all assessment is subjective, an ‘objective’ meritocracy is a tantalizing illusion that is pervasive in academia.

In referring to the candidate, use language that amplifies their formal title or position (e.g., “Assistant Professor”) rather than language that can detract from their credibility (e.g., “junior scholar,” “early-career”). Throughout, we recommend you use “Dr.” or another appropriate title rather than a first name (Figure 1 middle, box 2), and that you consider how the scholar you are evaluating chooses to identify in public forums and refers to themselves professionally, and follow their lead.

The bulk of a tenure and promotion letter rests on the accomplishments of the candidate. Here, it is vitally important that you name all of the candidate’s accomplishments (Figure 1 middle, box 3). That is, in addition to mentioning traditional scholarship (papers, books, citations, invited talks, grants), you can expand your own – and the readers’ – notion of what a scholarly accomplishment is. For example, you should call attention to: grant applications submitted (and re-submitted), symposia organized, spaces and classes created, leadership and service to the department and academic community, leadership to and education of the community outside of academia, creation of public policy and impact on public health, and participation in public relations or recruiting efforts. When possible, frame this as scholarship rather than service, because many of these achievements reflect the scholar’s standing in the field.

We also encourage you to give context to how the scholar provides novel input, lays important groundwork, encourages you to think differently about your work, challenges the field with a different perspective, or moves the field forward. If their contributions are non-traditional and span a wide range, you can highlight the range and quality of the various kinds of work they have completed (however, be careful to not emphasize effort over ability, e.g., “highly motivated”). Highlighting this broad range of accomplishments, even when they do not fit into the traditional metrics or definitions of scholarship, serves both to influence letter readers directly, and to present arguments to be used by internal advocates for the candidate.

For Black and other historically marginalized scholars in particular, recognize explicitly the candidate’s experiences and characteristics that bring wisdom and perspective beyond chronological years and official titles (Figure 1 middle, box 4). Those life experiences and identity characteristics (such as engaging in outreach programs, being an immigrant or international scholar, coming from a disadvantaged, under-resourced, or other path that has been historically underrepresented in academia) provide unique perspectives that enhance their environment. An anti-racist letter should also reflect a broad understanding of academic leadership as including collective and collaborative approaches. You can acknowledge the candidate’s collaborations, the expertise they bring to group projects, and how they connect with the community within and beyond their institution.

An important aspect of contribution to scholarly work and discourse is mentoring, which is often disproportionately done by Black and other historically marginalized scholars. In your letter, elaborate on the candidate’s mentorship (Figure 1 middle, box 5): include the number of mentees (direct and indirect) that rely on the candidate for support and note the contributions and successes of the candidate’s mentees and advisees. You can also include a statement about how the presence and/or work of the candidate creates a space of comfort for trainees and colleagues who do not traditionally feel welcome in academia (Chaudhary and Berhe, 2020). Acknowledge how the presence, actions, and intellectual contributions of the candidate draw developing scholars to the department/institution. Recognize and call attention to the time-consuming, but not consistently valued, public-relations work and other service work often required of marginalized scholars (Gewin, 2020).

We encourage you to add literature-supported encouragement for evaluators to account for systemic racism in academia (Figure 1 middle, box 6). For example, you can include “Given the known racial disparities in grant funding (Taffe and Gilpin, 2021) and publication rates (Lerback et al., 2020), and the epistemic exclusion of minoritized faculty (Settles et al., 2022),...” to provide context for your statements. It is important here to account for the many interpersonal and institutional barriers experienced by Black scholars, and to critique the devaluation of their work that provides tangible benefits to the university but is often unappreciated (Rodríguez et al., 2015). It may be helpful to explicitly state “even though the evaluation criteria do not consider [service/outreach/etc.], I include my assessment in this area given the vital importance of these contributions to the department and the field, and research on disproportionate service done by scholars of Color.” We recommend emphasizing that achievement in spite of the systemic barriers enhances the value of the scholar’s accomplishments rather than offering such barriers as a rationale for any potential perceived weaknesses.

We recommend you avoid (and ignore requests for) reductive comparisons to an arbitrary standard, a model/prototype, or a scholar at another institution (Figure 1 middle, box 7). Such comparisons cannot account for the varied intersecting identities and experiences of different scholars.

Finally, check-in with yourself about your goals in taking an anti-racist approach to letter-writing, and ensure that you reflected them well in your letter (Figure 1 middle, box 8). This approach is not about diluting the quality of tenured faculty or lowering the bar for promotion, but rather critiquing the devaluation of many types of scholarly contributions and recognizing the importance of such work both to the scholar’s institution and to their field of study.

After writing the letter

You can still do more. First, now that you are familiar with the work of this scholar in your field, make sure to cite them in your own work wherever appropriate (Figure 1 bottom, box 1). Racial disparities in whose work is cited persist across a variety of disciplines (Ray, 2018; Shirani, 2021). As you might do for junior scholars you already know well, you can also reach out to the candidate to convey your appreciation of their scholarly work and offer specific support or mentorship, such as inviting them to give a talk at your department (Figure 1 bottom, box 2). Do be attentive and respect their preferences if they decline your offer. If the junior scholar holds a marginalized identity and does take you up on the offer, educate yourself on how to mentor them in a way that supports and respects their goals and values rather than suggest they adopt yours (a great starting point is Fryberg and Gerken, 2012; Fryberg and Martínez, 2014; Martinez-Cola, 2020).

Regardless of whether you connect directly, you can support the candidate through sponsorship and nominations (Figure 1 bottom, box 3). For instance, you may identify an award for which you can nominate them based on all you learned while preparing your letter, or invite them to contribute a paper to a journal in which you are an editor. Additionally, you can broaden the network of people who are familiar with their scholarship, by inviting them to participate in a colloquium or to present their work at a conference you are organizing, including their work for discussion in a local journal club, and/or recommending their research group to graduate students and postdocs.

These actions on your part will not only benefit the scholar, they will also serve to educate your colleagues on the scholarship of this particular person, and on similar types of work they may be unfamiliar with (and might be called upon to evaluate in tenure and promotion letters in the future). Additionally, after following these suggestions for writing anti-racist tenure letters, consider expanding your anti-racism work by advocating for changes to the promotion criteria at your own institution drawing on the considerations outlined here.

Finally, as an intentionally anti-racist letter writer, we hope you will join a list of letter writers who have committed to using these guidelines (to join, fill in this form: https://forms.gle/4F4hBb9MNsrwdEDz6). This list (bit.ly/TenureEquity) will serve as a public resource for candidates and universities looking for anti-racist letter-writers.

We note that these ‘after writing’ steps are appropriate not only for scholars at the tenure/promotion career stage. Many early-career scholars who are marginalized in their field do not have a ‘natural’ mentoring and support network and could benefit from proactive acknowledgment and support.

Conclusion

The guidance we provided above is based on our current best understanding of the nature of ‘white supremacy culture’ in academia and how to counteract it within the tenure recommendation letter. While our process is based on strong theoretical foundations (Okun, 2021) and shaped by the input of a diverse range of scholars and the leadership of the Academics for Black Survival and Wellness organization, these guidelines cannot perfectly apply to all situations and will need revision and reimagining over time. We recognize that the role of an external evaluator for a tenure candidate is one in which faculty have substantial freedom to adopt an anti-racist approach. We further suggest that scholars consider the many ways their anti-racist commitments can inform all aspects of their scholarly work (e.g., conducting peer review, see Itchuaqiyaq and Walton, 2021) and can be expanded to bring about systemic changes in their institutions.

To be sure, anti-racist tenure letters may be met with resistance and even backlash by tenure committees, as many academics are (implicitly) committed to maintaining power structures that are familiar to them, and that confer them with outsized power and privilege. We suggest to directly rebut, in your letter, what might traditionally be considered ‘weaknesses’ in the applicant’s file, by explicitly addressing why you do not consider these as weaknesses. This can be done throughout your letter (and we have suggested specific ideas for how to do this in the above recommendations), as well as in an explicit rebuttal paragraph, as we are doing here. Such resistance-anticipating arguments will provide much needed ammunition for other advocates involved in the tenure process at the candidate’s home institution.

Unfortunately, our suggestions cannot ameliorate the persistent opportunity gaps and discrimination that Black scholars face in their educational and professional careers. We offer these recommendations as one avenue for resisting ‘white supremacy culture’ in academia with the understanding that such resistance must be accompanied by systemic reforms. Even as some institutions introduce diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) requirements for tenure or forge new DEI-focused pathways to tenure, the success of such projects in creating an inclusive and equitable academic culture will require openly acknowledging racism in academia (Gosztyla et al., 2021), taking a proactive approach to an inclusive workplace culture and retaining Black scholars (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022), and introducing changes to tenure evaluation policies (e.g. recognizing the myriad biases in student evaluations of teaching) and practices (e.g, nomination and selection of letter writers, instructions provided to letter writers, how evaluators are trained).

While individual letter writers have substantial input in the tenure process, tenure decisions ultimately rest with deans, provosts, presidents, and boards. These power-holders are uniquely situated to reimagine and advocate for a tenure process that centers equity, inclusion, and justice rather than a process that reproduces ‘white supremacy culture’. In addition to writing anti-racist letters, we encourage you to advocate that the power-holders in your own institution reimagine tomorrow’s academia and proceed with haste to make that dream a reality. It is in their – and all of our – hands.

Data availability

No data were generated for this study.

References

-

WebsiteUnconscious racial bias can creep into recommendation letters – here’s how to avoid itThe Muse. Accessed October 12, 2022.

-

Ten simple rules for building an antiracist labPLOS Computational Biology 16:e1008210.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008210

-

BookBlack feminist thought and qualitative research in educationOxford Research Encyclopedia of Education.https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1194

-

Researcher positionality - a consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research - a new researcher guideShanlax International Journal of Education 8:1–10.https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

-

Anti-Black practices take heavy toll on mental healthNature Human Behaviour 5:410.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01058-z

-

WebsiteWriting strategies: What’s your positionalityThe Weingarten Blog. Accessed October 12, 2022.

-

Website'I was fed up’: How #BlackInTheIvory got started, and what its founders want to see nextThe Chronicle of Higher Education. Accessed October 12, 2022.

-

Academic bullying: A barrier to tenure and promotion for African-American facultyFlorida Journal of Educational Administration & Policy 5:1–13.

-

BookTwins separated at birth? critical moments in cross-race mentoring relationshipsIn: Dace KL, editors. Unlikely Allies in the Academy: Women of Color and White Women in Conversation. Routledge. pp. 1–216.

-

BookThe truly diverse facultyIn: Fryberg SA, Martínez EJ, editors. The Future of Minority Studies. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 4–34.https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137456069

-

The ranking regime and the production of knowledge: implications for academiaEducation Policy Analysis Archives 22:31.https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22n31.2014

-

BookEmbedded colonial power: how global ranking systems set parameters for the recognition of knowers, knowledge, and the production of knowledgeIn: Gonzales LD, editors. In World University Rankings and the Future of Higher Education. IGI Global. pp. 302–327.https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0819-9.ch016

-

Subverting and minding boundaries: the intellectual work of womenThe Journal of Higher Education 89:677–701.https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1434278

-

Responses to 10 common criticisms of anti-racism action in STEMMPLOS Computational Biology 17:e1009141.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009141

-

Faculty service loads and gender: are women taking care of the academic family?Research in Higher Education 58:672–694.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-017-9454-2

-

BookA Race Is A Nice Thing to Have: A Guide to Being A White Person or Understanding the White Persons in Your LifeCognella.

-

What have you done for me lately? Black female faculty and ‘talking back’ to the tenure process at PWIsWomen & Language 35:99–102.

-

Underrepresented faculty play a disproportionate role in advancing diversity and inclusionNature Ecology & Evolution 3:1030–1033.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0911-5

-

African American female professors’ strategies for successful attainment of tenure and promotion at predominately white institutions: it can happenEducation, Citizenship and Social Justice 10:133–151.https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197915583934

-

Ten simple rules for writing compelling recommendation lettersPLOS Computational Biology 17:e1008656.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008656

-

Intersectional inequalities in sciencePNAS 119:e2113067119.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2113067119

-

Association between author diversity and acceptance rates and citations in peer‐reviewed earth science manuscriptsEarth and Space Science 7:e2019EA000946.https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EA000946

-

Collectors, nightlights, and allies, oh myUnderstanding and Dismantling Privilege 10:61–82.

-

Conditions of visibility: an intersectional examination of Black women’s belongingness and distinctiveness at workJournal of Vocational Behavior 113:143–152.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.09.008

-

Critical consciousness of anti-Black racism: a practical model to prevent and resist racial traumaJournal of Counseling Psychology 68:1–16.https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000430

-

ReportPromotion, tenure, and advancement through the lens of 2020: Proceedings of a workshop—in briefWashington, DC, United States: The National Academies Press.

-

Community engagement is …: revisiting boyer’s model of scholarshipHigher Education Research & Development 39:1232–1246.https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1712680

-

Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax?BMC Medical Education 15:1–5.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

-

It is time to stop racial exclusion in scholarly citationsJournal of Bioethical Inquiry 18:547–548.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-021-10137-9

-

The burden of invisible work in academia: social inequalities and time use in five university departmentsHumboldt Journal of Social Relations 39:228–245.

-

The uphill climb: scholars see little progress in efforts to diversify faculty ranksDiverse Issues in Higher Education 29:16–17.

-

WebsiteThe condition of education 2017 (NCES 2017-144). Characteristics of postsecondary facultyAccessed October 12, 2022.

Decision letter

-

Julia DeathridgeReviewing Editor; eLife, United Kingdom

-

Peter RodgersSenior Editor; eLife, United Kingdom

In the interests of transparency, eLife publishes the most substantive revision requests and the accompanying author responses.

Decision letter after peer review:

Thank you for submitting your article "A guide for writing anti-racist tenure and promotion letters" to eLife for consideration as a Feature Article. Your article has been reviewed by two peer reviewers, and the evaluation has been overseen by two members of the eLife Features Team (Julia Deathridge and Peter Rodgers). The following individual involved in the review of your submission has agreed to reveal their identity: Isis Settles.

We have drafted this decision letter to help you prepare a revised submission.

Summary

This article provides a well-thought-out set of recommendations for how senior academics can write anti-racist tenure letters that better recognize the contributions of Black scholars. The authors – a group of researchers who took part in an Academics for Black Survival and Wellness workshop – advise what academics should do before writing the letter, what should (and should not be) included, and what letter writers can do after to continue to support faculty from marginalized groups. The manuscript brings much-needed attention to the power senior academics hold when writing these documents and avoids deficit framing, which is critical for an anti-racist approach. If widely adopted, these guidelines could have an incredible impact and lead to a more inclusive academic culture. However, there are a few points that need to be addressed before the article can be accepted for publication.

Essential Revisions

1) The authors introduce white supremacy culture as a cultural force that requires disrupting and introduce reconsidering tenure letters as a mechanism to do so. I'm concerned that this section seems too abstract, particularly given the concrete suggestions provided later. Could the authors ground this section further? For example, the last sentence currently reads: "We have a right to shape our shared culture and to promote an academic community that recognizes and benefits from the wisdom of all people who participate in academia." Can I suggest changing this to: "Those of us committed to disrupting this implicit and harmful culture have a right and obligation to actively promote an academic community that recognizes and benefits from the expertise of all people who participate in academia. One way to accomplish this on an individual level is to reconsider how we write letters of assessment, including tenure letters, so that they embody the cultural shift we'd like to see."

2) In the Okun (2021) framework, perfectionism includes the idea that there is one way of doing things and objectivity is possible. I wonder if there is value in tying this to the positivist and post-positivist values of science that have been adopted by many fields. I think the values of science are invisible to most scholars so it could be helpful to discuss how these are just types of epistemologies of science but there are other knowledge systems that exist and are used.

3) On p. 4, you note that writers should "Consider how to communicate the importance of such work that is not traditionally valued by academia." I wonder if you have ideas about how letter writers can educate themselves in this area – both in the traditional values of academia (Leslie Gonzales at Michigan State University has done work in this area) and the specific contributions of a scholar's work. For individuals doing more traditional or mainstream work, they may not have considered the contributions of work on the margins which will make it challenging for them to communicate those things effectively.

4) On page 5 (lines starting at 183) where you talk about accomplishments, I suggest two additions. First, broadening notions of impact and contribution beyond the usual metrics to include things like impact on public policy, public health, community engagement, teaching, and education, etc. Second, when scholars do public or engaged scholarship, it is often considered to be service. Where possible, writers should frame this as scholarship because it is and that's where it usually counts most for promotion.

5) Although you recommend that writers not feel tied to only addressing the criteria shared by the institution requesting the letter (page 5 – line 222), I would state this more explicitly. In my letters for scholars from marginalized groups, I often will say something like "even though the evaluation criteria don't consider X (e.g., service), I include my assessment in this area given the research on disproportionate service labor done by scholars of color."

6) Although I appreciate the framing of letter writers as individuals who may not be able to change the broader system, I encourage the authors to include some advice about making structural changes in the "after the letter" section. For example, individuals could seek to educate their colleagues about the scholarship of the person they evaluated and similar types of work (through invited speakers, journal club selections, etc.). You have suggested that they bring in scholars as speakers to benefit the scholar's career, but I'm suggesting using these activities to educate others who may find themselves in a position to also write letters for scholars from marginalized groups. Individuals could also work to change their internal promotion criteria through their roles as senior scholars. This combination of individual and structural changes may allow for change to (hopefully) happen on a wider and faster scale.

7) I think the authors have to confront the very real possibility of resistance and backlash these letters may come up against. In the sections called Before Writing the Letter and When Writing the Letter, I'd recommend adding suggestions for how to directly rebut what might be considered "weaknesses" in the applicant's file by detractors insistent upon maintaining academia's current culture. Explicitly addressing why the letter writer does not consider these weaknesses provides much-needed ammunition for other advocates involved in the tenure process at the applicant's home institution.

8) Please consider including the following citations:

a) The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Promotion, Tenure, and Advancement through the Lens of 2020: The next normal for the advancement of tenure and non-tenure-track faculty (https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26405/promotion-tenure-and-advancement-through-the-lens-of-2020-proceedings) – this series of papers may offer additional ideas for advice for equitable evaluations

b) Intersectional inequalities in science (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2113067119) talks about gender and racial bias in citation practices

c) Gonzales, L. D. (2018). Subverting and minding boundaries of knowledge production in academe: The intellectual work of women. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(3) 1-25. – Describes values in academia from a historical perspective.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79892.sa1Author response

Essential Revisions

1) The authors introduce white supremacy culture as a cultural force that requires disrupting and introduce reconsidering tenure letters as a mechanism to do so. I'm concerned that this section seems too abstract, particularly given the concrete suggestions provided later. Could the authors ground this section further? For example, the last sentence currently reads: "We have a right to shape our shared culture and to promote an academic community that recognizes and benefits from the wisdom of all people who participate in academia." Can I suggest changing this to: "Those of us committed to disrupting this implicit and harmful culture have a right and obligation to actively promote an academic community that recognizes and benefits from the expertise of all people who participate in academia. One way to accomplish this on an individual level is to reconsider how we write letters of assessment, including tenure letters, so that they embody the cultural shift we'd like to see."

Thank you for identifying that this section was too abstract. We have adopted your suggestion verbatim, but also rewrote the section introducing White Supremacy Culture and tried to make it more explicit, give a concrete example, and be more prescriptive about what is needed:

“These “White Supremacy Culture” values (Okun, 2021) are not a necessity in academia. Most of us, having been trained and steeped in this culture for years, may not even recognize these invisible but ever-present “rules of the game” despite the fact that these rules limit creativity and inclusion. Naming these values as ones we have adopted makes clear that they are not axioms of academic culture. There are alternatives. Those of us committed to disrupting theis implicit and harmful culture have a right and obligation to actively promote an academic community that recognizes and benefits from the expertise of all people who participate in academia. One way to accomplish this on an individual level is to reconsider how we write letters of assessment, including tenure letters, so that they embody the cultural shift we'd like to see.

In particular, the academic profession was developed to have strict boundaries about who is allowed to be a part of the profession and what work is valued. Western scientific approaches (i.e.g., objectivity, linearity, generalizability, and detachment) have long been the standard for evaluating academic rigor and membership into this highly selective profession. Thus, Black scholars engaging in community- focused research and racial- justice work are often evaluated negatively because their work is viewed as not being objective and their advocacy is viewed as problematic (Gonzales, 2018). Indeed, Black scholars are overrepresented in topics related to racial discrimination and African studies but often cited less than other racial groups of scholars (Kozlowski et al., 2022). Therefore, in evaluation processes, like tenure and promotion, their research is often already being undervalued by evaluators enmeshed in “White Supremacy Culture.” Anti-racist tenure and promotion letters provide an avenue of intervention and advocacy to challenge the exclusionary and harmful aspects of academia. In evaluating scholarship that does not necessarily conform to “White Supremacy Culture” values, we must recognize that our personal biases influence both our scientific practice and our tendency to uphold these values of scientific pursuit. If we are to move beyond these exclusionary practices, we must recognize these biases in all of our academic practices and value other knowledge systems beyond that of the ‘traditional’ epistemology of science.” (pp. 2)

2) In the Okun (2021) framework, perfectionism includes the idea that there is one way of doing things and objectivity is possible. I wonder if there is value in tying this to the positivist and post-positivist values of science that have been adopted by many fields. I think the values of science are invisible to most scholars so it could be helpful to discuss how these are just types of epistemologies of science but there are other knowledge systems that exist and are used.

We wholeheartedly agree, and our impetus in introducing Okun’s framework is to clarify that there are alternatives – we can adopt other values, we can value other ways of knowing, and other knowledge systems. We have now tried to say this more explicitly when introducing White Supremacy Culture (see the text reproduced above). In particular, our call to “recognize that our personal biases influence both our scientific practice and our tendency to uphold these values of scientific pursuit. If we are to move beyond these exclusionary practices, we must recognize these biases in all of our academic practices and value other knowledge systems beyond that of the ‘traditional’ epistemology of science.” is trying to explicitly name the work that must be done, in terms of being aware of these biases, recognizing their possible effects, and working to counteract them, as per the post-positivism framework (we decided to not explicitly name post-positivism as readers may not be familiar with that term).

3) On p. 4, you note that writers should "Consider how to communicate the importance of such work that is not traditionally valued by academia." I wonder if you have ideas about how letter writers can educate themselves in this area – both in the traditional values of academia (Leslie Gonzales at Michigan State University has done work in this area) and the specific contributions of a scholar's work. For individuals doing more traditional or mainstream work, they may not have considered the contributions of work on the margins which will make it challenging for them to communicate those things effectively.

You are correct, and this is a tough one. Most of us have been learning about these issues for years – from social media, as well as more formal training (A4BL) and readings. In the spirit of acknowledging multiple ways of learning and knowing, we have added pointers both to scholarly work (thank you for pointing out Leslie Gonzalez, who we now refer to) as well as other sources of knowledge (Twitter, Facebook):

“As a final preparatory step (Figure 1 top, box 3), research the candidate’s CV, professional website, and public-facing social media to learn more about the candidate’s influential work inside and outside of academia (e.g., DEI work, collaborative work, leadership). Consider the multiple ways that a research area has been impacted by the presence and contributions of the scholar and how to communicate the importance of any work that is not traditionally valued by academia. It may be helpful to familiarize yourself with the embedded values of academia, through reading Okun (2021) or the work of Dr. Leslie Gonzales (e.g., Gonzales and Waugman, 2016; Gonzales and Núñez, 2014), in order to recognize the limitations of traditional scholarship as the only currency of contribution to academia. This critical awareness will enable you to write a letter that speaks to those values while challenging tenure and promotion committees to expand their review beyond those values. It may be useful to follow discussions and groups on social media (Twitter, Facebook) that are outside your immediate community, especially of scholars with identities other than your own. This can help to expand your understanding of what is valuable in academia and the hurdles Black scholars may face, and provide you with ideas on how to communicate this new knowledge to others.” (pp. 5)

Inspired by your suggestion, and in response to comment 7 below, we also note, in a later section, how this self-education can translate to wording in the letter that will help advocates in the committee argue for inclusion of not-traditionally-valued work and achievements as part of the candidate’s recognized scholarship:

“Highlighting this broad range of accomplishments, even when they do not fit into the traditional metrics or definitions of scholarship, serves both to influence letter readers directly, and to present arguments to be used by internal advocates for the candidate.” (pp. 5)

4) On page 5 (lines starting at 183) where you talk about accomplishments, I suggest two additions. First, broadening notions of impact and contribution beyond the usual metrics to include things like impact on public policy, public health, community engagement, teaching, and education, etc. Second, when scholars do public or engaged scholarship, it is often considered to be service. Where possible, writers should frame this as scholarship because it is and that's where it usually counts most for promotion.

Thank you for these excellent suggestions. We have now added these to the text as follows:

“The bulk of a tenure and promotion letter rests on the accomplishments of the candidate. Here, it is vitally important that you name all of the candidate’s accomplishments (Figure 1 middle, box 3). That is, in addition to mentioning traditional scholarship (papers, books, citations, invited talks, grants), you can expand your own – and the readers’ – notion of what a scholarly accomplishment is. Grant applications submitted (and re-submitted), symposia organized, spaces and classes created, leadership and service to the department, profession, and academic community, leadership to and education of the community outside of academia, creation of public policy and impact on public health, and participation in public relations or recruiting efforts are all important accomplishments that you should call attention to. When possible, frame this as scholarship, rather than service, because many of these achievements reflect the scholar’s standing in the field.” (pp. 5)

5) Although you recommend that writers not feel tied to only addressing the criteria shared by the institution requesting the letter (page 5 – line 222), I would state this more explicitly. In my letters for scholars from marginalized groups, I often will say something like "even though the evaluation criteria don't consider X (e.g., service), I include my assessment in this area given the research on disproportionate service labor done by scholars of color."

This is a great way of framing your comments in letters. We have now added this sentence as part of step 6 “during”, on page 7:

“It is important here to account for the many interpersonal and institutional barriers experienced by Black scholars, and to critique the devaluation of their work that provides tangible benefits to the university but is often unappreciated (e.g., Rodríguez, Campbell, and Pololi, 2015). It may be helpful to explicitly state “even though the evaluation criteria do not consider [service/outreach/etc.], I include my assessment in this area given the vital importance of these contributions to the department and the field, and research on disproportionate service done by scholars of Color.” (pp. 7)

6) Although I appreciate the framing of letter writers as individuals who may not be able to change the broader system, I encourage the authors to include some advice about making structural changes in the "after the letter" section. For example, individuals could seek to educate their colleagues about the scholarship of the person they evaluated and similar types of work (through invited speakers, journal club selections, etc.). You have suggested that they bring in scholars as speakers to benefit the scholar's career, but I'm suggesting using these activities to educate others who may find themselves in a position to also write letters for scholars from marginalized groups. Individuals could also work to change their internal promotion criteria through their roles as senior scholars. This combination of individual and structural changes may allow for change to (hopefully) happen on a wider and faster scale.

Yes! Ideally all this would happen. We would love it if these recommendations had impact beyond individual letters and careers, to more systemic change and wider education. This is a great suggestion. We have now added a paragraph that explicitly discusses this at the end of the “after the letter” section, in addition to the relevant text we already had in the conclusion section:

“These actions on your part will not only benefit the scholar, they will also serve to educate your colleagues on the scholarship of this particular person, and on similar types of work they may be unfamiliar with (and might be called upon to evaluate in tenure and promotion letters in the future). Indeed, after following these suggestions for writing anti-racist tenure letters, consider expanding your anti-racism work by advocating for changes to the promotion criteria at your own institution drawing on the considerations outlined here.“ (pp. 7)

“We recognize that the role of an external evaluator for a tenure candidate is one in which faculty have substantial freedom to adopt an anti-racist approach. We further suggest that scholars consider the many ways their anti-racist commitments can inform all aspects of their scholarly work (e.g., conducting peer reviews, see Itchuaqiyaq and Walton, 2021), and can be expanded to bring about systemic changes in their institutions.” (pp. 8)

Previous relevant text in our conclusions section:

“Even as some institutions introduce diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) requirements for tenure or forge new DEI-focused pathways to tenure, the success of such projects in creating an inclusive and equitable academic culture will require openly acknowledging racism in academia (Gosztyla et al., 2021), taking a proactive approach to an inclusive workplace culture and to retaining Black scholars (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022), and instituting changes to tenure evaluation policies (e.g., recognizing the importance of community-based scholarship, recognizing the myriad biases in student evaluations of teaching) and practices (e.g., nomination and selection of letter writers, instructions provided to letter writers, how evaluators are trained). While individual letter writers have substantial input in the tenure process, tenure decisions ultimately rest with deans, provosts, presidents, and boards. These power-holders are uniquely situated to reimagine and advocate for a tenure process that centers equity, inclusion, and justice rather than a process that reproduces “White Supremacy Culture.” In addition to writing anti-racist letters, we encourage you to advocate that the power-holders in your own institution reimagine tomorrow’s academia and proceed with haste to make that dream a reality. It is in their – and all of our – hands.” (pp. 8)

7) I think the authors have to confront the very real possibility of resistance and backlash these letters may come up against. In the sections called Before Writing the Letter and When Writing the Letter, I'd recommend adding suggestions for how to directly rebut what might be considered "weaknesses" in the applicant's file by detractors insistent upon maintaining academia's current culture. Explicitly addressing why the letter writer does not consider these weaknesses provides much-needed ammunition for other advocates involved in the tenure process at the applicant's home institution.

This is, in many senses, the elephant in the room. We have intentionally chosen to write from a positive perspective that assumes that letter writers (or at least, those reading our paper) are well-intentioned but ill-equipped to act on their intentions. However, not everyone is, and as pointed out implicitly in some of the above comments, even if the letter-writer is doing anti-racist work, the committee reading the letter may not be on board with these values (yet). As such, the letter writer themselves may have to confront the very real possibility of resistance and backlash.

To address this, and through that model to letter writers what they can do as well, we have added what is known as a “To be sure” paragraph in op eds – a direct address to the most commonly heard criticism of what we are arguing for. If this is not what you had in mind, or if you have additional suggestions for how to address resistance and backlash, we are happy to add to this:

“To be sure, anti-racist tenure letters may be met with resistance and even backlash by tenure committees, as many academics are (implicitly) committed to maintaining power structures that are familiar to them, and that confer them with outsized power and privilege. We suggest to directly rebut, in your letter, what might traditionally be considered "weaknesses" in the applicant's file, by explicitly addressing why you do not consider these as weaknesses. This can be done throughout your letter (and we have suggested specific ideas for how to do this in the above recommendations), as well as in an explicit rebuttal paragraph, as we are doing here. Such resistance-anticipating arguments will provide much-needed ammunition for other advocates involved in the tenure process at the candidate's home institution.” (pp. 8)

In addition, in reply to the above comments, in several places we have buffered up suggestions for explicitly addressing why issues that are traditionally considered weaknesses, are not, and how this can help internal advocates.

8) Please consider including the following citations:

a) The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Promotion, Tenure, and Advancement through the Lens of 2020: The next normal for the advancement of tenure and non-tenure-track faculty (https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26405/promotion-tenure-and-advancement-through-the-lens-of-2020-proceedings) – this series of papers may offer additional ideas for advice for equitable evaluations

b) Intersectional inequalities in science (https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2113067119) talks about gender and racial bias in citation practices

c) Gonzales, L. D. (2018). Subverting and minding boundaries of knowledge production in academe: The intellectual work of women. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(3) 1-25. – Describes values in academia from a historical perspective.

Thank you for these excellent suggestions. We have now incorporated citations (b) and (c) in our introduction and discussion of White Supremacy Culture, as a practical example of how this culture harms Black scholars and how anti-racist tenure and promotion practices may help, and cite (a) in the conclusion paragraph:

In particular, the academic profession was developed to have strict boundaries about who is allowed to be a part of the profession and what work is valued. Western scientific approaches (i.e.g., objectivity, linearity, generalizability, and detachment) have long been the standard for evaluating academic rigor and membership into this highly selective profession. Thus, scholars of Color engaging in community- focused research and racial- justice work are often evaluated negatively because their work is viewed as not being objective and their advocacy is viewed as problematic (Gonzales, 2018). Indeed, Black scholars are overrepresented in topics related to racial discrimination and African studies but often cited less than other racial groups of scholars (Kozlowski et al., 2022). Therefore, in evaluation processes, like tenure and promotion, their research is often already being undervalued by evaluators enmeshed in “White Supremacy Culture.” Anti-racist tenure and promotion letters provide an avenue of intervention and advocacy to challenge the exclusionary and harmful aspects of academia. In evaluating scholarship that does not necessarily conform to “White Supremacy Culture” values, we must recognize that our personal biases influence both our scientific practice and our tendency to uphold these values of scientific pursuit. If we are to move beyond these exclusionary practices, we must recognize these biases in all of our academic practices and value other knowledge systems beyond that of the ‘traditional’ epistemology of science.” (pp. 2)

“Even as some institutions introduce diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) requirements for tenure or forge new DEI-focused pathways to tenure, the success of such projects in creating an inclusive and equitable academic culture will require openly acknowledging racism in academia (Gosztyla et al., 2021), taking a proactive approach to an inclusive workplace culture and to retaining Black scholars (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022), and instituting changes to tenure evaluation policies (e.g., recognizing the importance of community-based scholarship, recognizing the myriad biases in student evaluations of teaching) and practices (e.g., nomination and selection of letter writers, instructions provided to letter writers, how evaluators are trained).” (pp. 8)

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79892.sa2Article and author information

Author details

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the creators and participants of the 2020, 2021 and 2022 Academics for Black Survival and Wellness trainings, particularly the teachings and inspirational anti-racist activism of Dr. Della Mosley, Dr. Carlton Green, and Adania Flemming. We look forward to furthering our learning at future A4BL trainings and encourage new participants to join us. This manuscript is the culmination of work by a working group that formed in the 2021 training. We thank Aditi Jayarajan and Dr. Caroline Storer for their recommendations and support in the initial stages of this project. We are also grateful to our reviewers and editors at eLife for their excellent suggestions for improving this manuscript. We acknowledge that the lands we inhabit were previously occupied by indigenous peoples who were, in many cases, forcibly removed, and that the physical academic spaces in which we work and from which we generated this collaborative product were built, in large part, using uncompensated and often forced labor of Black people.

Publication history

- Received:

- Accepted:

- Version of Record published:

Copyright

© 2022, The A4BL Anti-racist Tenure Letter Working Group

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 5,830

- views

-

- 528

- downloads

-

- 7

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 7

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.79892