Dating the origin and spread of specialization on human hosts in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes

Figures

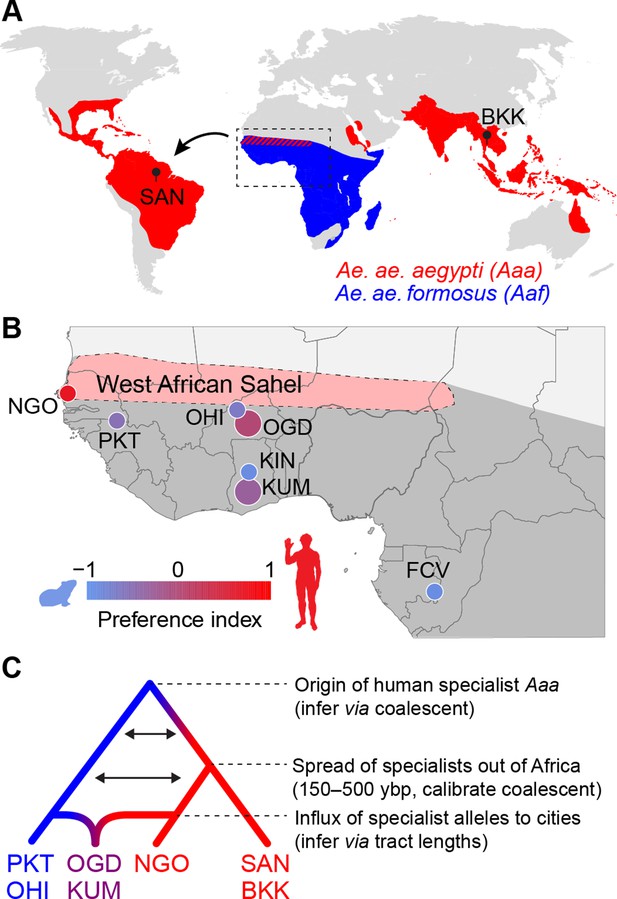

Dating the origin and spread of the human-specialist form of Aedes aegypti.

(A) The human-specialist form of Aedes aegypti aegypti (Aaa) is thought to have originated in West Africa, before invading the Americas in association with the Atlantic Slave Trade and subsequently spreading across the global tropics. (B) Present-day Ae. aegypti populations in West Africa vary in their preference for human hosts. Large cities (e.g. KUM, OGD) are shown as larger circles, while small towns are shown as smaller circles. Map region corresponds to the inset in panel A. Pink shading marks the intensely seasonal Sahel region, where human specialists likely originated. Behavioral data taken from Rose et al., 2020. (C) The timing of major events in the evolutionary history of human-specialist populations (red lineages) can be inferred using population genomic approaches, such as coalescent analysis (for older events) and tract length analysis (for more recent events). SAN, Santarem, Brazil; BKK, Bangkok, Thailand; NGO, Ngoye, Senegal; PKT, PK10, Senegal; OHI, Ouahigouya, Burkina Faso; OGD, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; KUM, Kumasi, Ghana; KIN, Kintampo, Ghana; FCV, Franceville, Gabon.

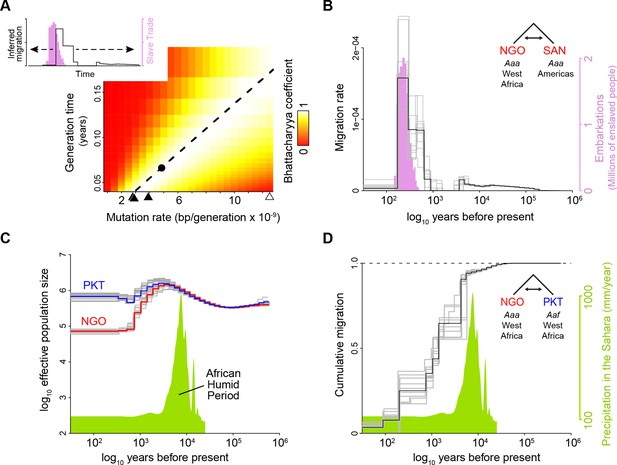

A calibrated coalescent scaling factor for Ae. aegypti suggests rapid evolution of human specialists at the end of the African Humid Period.

(A–B) Calibration of a coalescent scaling factor for Ae. aegypti. (A), The Bhattacharyya coefficient reveals the extent of overlap between the timing of the Atlantic Slave Trade (based on historical records Slave Voyages, 2023, pink distribution in inset) and inferred migration of Aaa out of Africa (based on cross-coalescent analysis, black line in inset) for given combinations of the mutation rate (μ) and generation time (g). A value of one indicates perfect correspondence through time and 0 indicates no overlap. Estimated mutation rates for three other insects (see Results) and Homo sapiens are marked along x-axis with closed and open triangles, respectively. y-axis ranges from the shortest to longest reasonable generation times for Ae. aegypti. The dashed line indicates the μ/g ratio that provides the strongest match between genomic and historical data. The dot marks the exact calibration used in the other panels (g=0.067, μ=4.85 × 10–9), but any combination of μ and g that falls along the line would produce identical results. (B) The inferred timecourse of migration of Aaa from West Africa to the Americas shown alongside the historical record of the Atlantic Slave Trade that was used for calibration. When populations first split, the MSMC-IM model infers an instantaneous ‘migration’ of haplotypes to the new population. Older migration events may correspond to older coalescent events due to recent admixture in NGO. (C–D). Cross-coalescent analysis of the timing of human specialization.(C) Inferred effective population sizes for West African Aaa (NGO) and Aaf (PKT) superimposed on Saharan rainfall data (inferred from Atlantic marine sediments Beserra et al., 2006). (D) Estimated cumulative migration between Aaa (NGO) and Aaf (PKT) is expected to plateau at 1 going backwards in time, when populations have merged into a single ancestral population. Populations diverged rapidly at the end of the African Humid Period. In all panels, gray lines represent bootstrap replicates. This figure highlights analyses relevant to key questions (migration rate for the invasion process, cumulative migration for the original split of specialists and generalists). Full analyses for all population pairs are shown in Figure 2—figure supplement 1.

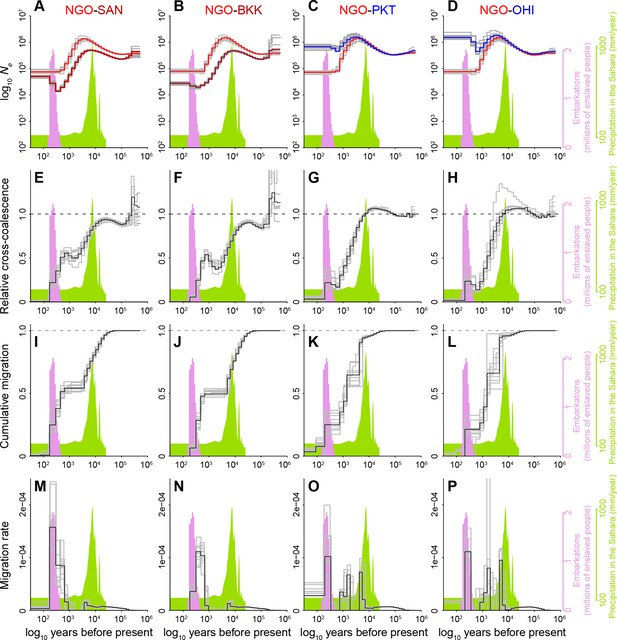

Full detail of cross-coalescent analyses comparing the Sahelian human specialists to invasive human specialists or nearby generalists.

For each population pair (i.e. column), we show MSMC2-inferred changes in effective population size over time (A–D), MSMC2-inferred relative cross-coalescence (expected to plateau at 1 when populations have merged into a single ancestral population) (E–H), MSMC-IM-inferred cumulative migration (also expected to plateau at one when populations have merged into a single ancestral population) (I–L), and MSMC-IM-inferred migration rate (fraction per generation) (M–P). First two columns show results for the Sahelian human-specialist population NGO compared to invasive human-specialist populations from Brazil (SAN; panels A, E, I, M) or Thailand (BKK; panels B, F, J, N). Note that invasive populations have both recent (hundreds of years, as expected) and much older (thousands of years) pulses of coalescence with NGO. The older signals likely arise from the fact that both NGO and invasives have somewhat mixed ancestry. NGO has experienced substantial admixture from nearby generalists in recent years and is, therefore, an imperfect proxy for the African human-specialists that gave rise to invasive populations. Likewise, invasive populations have likely experienced gene flow from other African generalist populations (e.g. in Angola, a major slave trading hub) (Schiffels and Wang, 2020) that diverged from West African generalists long before they gave rise to specialists. The last two columns show results for the Sahelian human-specialist population NGO compared to nearby generalist populations from Senegal (PKT; panels C, G, K, O) or Burkina Faso (OHI; panels D, H, L, P). In addition to the signal of rapid divergence/migration ~5000 years ago, we also observe increased divergence/migration during the Atlantic Slave Trade – this signal may reflect increased movement within the continent also associated with the Atlantic Slave Trade, or could reflect other changes in patterns of gene flow during this period of time.

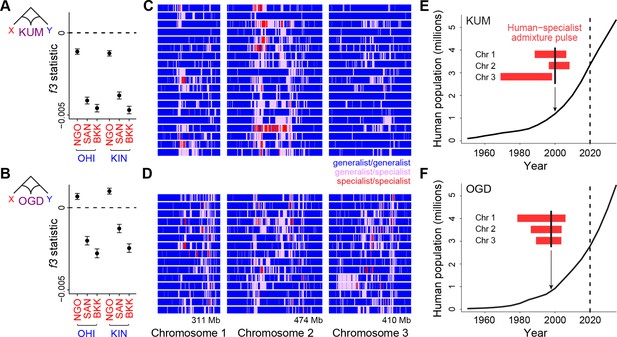

Long tracts of human-specialist ancestry in rapidly growing cities suggest a recent influx associated with modern urbanization.

(A–B) f3 analysis confirming that Kumasi, Ghana (A, KUM) and Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso (B, OGD) can be modeled as a product of admixture between generalist and human-specialist Ae. aegypti populations. Νegative values provide evidence of admixture. Εrror bars show 95% jackknife confidence intervals. (C–D) Distribution of tracts of human-specialist ancestry (purple, heterozygous; red, homozygous) across 19 unrelated KUM genomes (C) and 15 unrelated OGD genomes (D). (E–F) The inferred timing of human-specialist admixture (red bars) overlaid on publicly available human population growth data and near-future growth projections for KUM (E) and OGD (F). Red bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals for each chromosome, and thick black lines mark the mean for all three chromosomes. Dashed lines mark the date when human population data were collected.

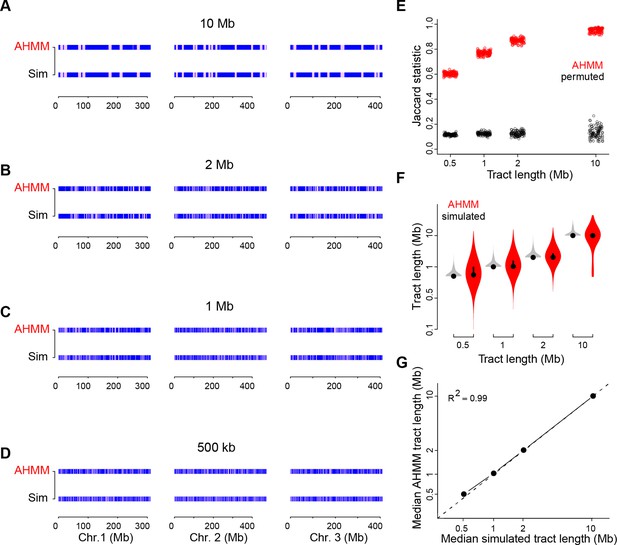

Simulations confirm the reliability of admixture analyses in West African cities.

(A–D) AncestryHMM (AHMM) analysis (top row of each panel) reliably detected simulated tracts of BKK ancestry (bottom row of each panel) in a OHI background with tract lengths of 500 kb (A), 1 Mb (B), 2 Mb (C), and 10 Mb (D). (E), Overlap between simulated and AHMM-inferred tracts as measured by the Jaccard statistic, which should take a value of zero in the case of no overlap and one in the case of perfect overlap. Overlap was strong for all four tract lengths (all permutation p<0.01), though longer tracts were more accurately detected. (F), AHMM-inferred tracts show a similar mean length to simulated tracts, though AHMM showed a broader distribution of tract lengths overall. Simulated tracts (gray) were all the same length, but overlapping tracts were merged, leading to some longer tracts. (G), Median simulated and AHMM-inferred tract lengths are concordant.

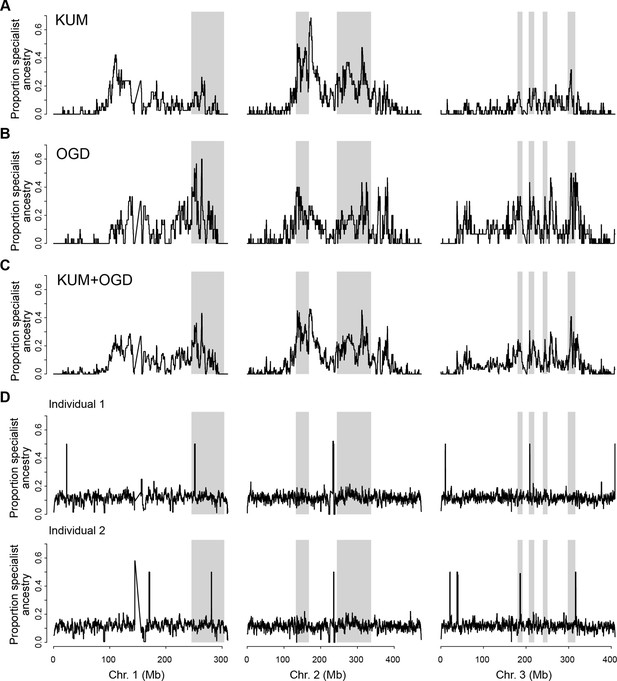

Tracts of human-specialist ancestry are concentrated in similar parts of the genome in Kumasi and Ouagadougou.

(A–B) Local fraction of ancestry derived from human specialists across the genome in KUM (A) and OGD (B) (using BKK and OHI as specialist and generalist reference panels, respectively). (C) As in panel A, but averaging across KUM and OGD. (D) Randomly simulated tracts of human-specialist ancestry (160 tracts of 2 Mb length per simulation, similar to the conditions observed in KUM and OGD) are evenly detected across the genome of two OHI individuals. A few small heterozygous tracts are detected across all simulations regardless of whether simulated tracts were placed in these locations, likely representing rare human-specialist tracts present in this otherwise unadmixed individual. The tracts detected across all simulations are in different locations in the two different individuals, providing further evidence that these signals are caused by rare human-specialist tracts in OHI and do not reflect a systematic feature of the analysis or reference panels. Gray shading represents the outlier regions previously identified as involved in human specialization (Rose et al., 2020).

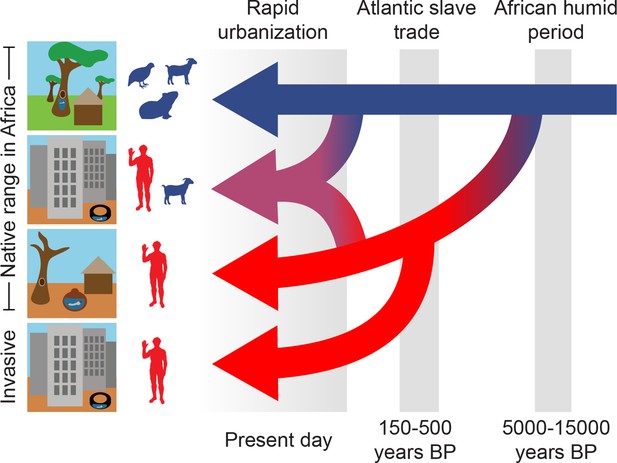

Three epochs define the origin and spread of the human-specialist form of Ae. aegypti.

Our analyses suggest that human-specialized Ae. aegypti rapidly diverged from their generalist counterparts after the end of the African Humid Period, with the emergence of settled human societies in intensely seasonal habitats with long, hot dry seasons. Human specialists then migrated from West Africa to the Americas during the Atlantic Slave Trade. Finally, we find evidence of a recent influx of human-specialist ancestry into the rapidly growing cities consistent with an ongoing shift in the ecology of Ae. aegypti in present-day Africa.