Examining the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cervical cancer screening practices among clinicians practicing in Federally Qualified Health Centers: A mixed methods study

Figures

Tables

Clinician characteristics and screening practices.

| Variable | Frequency | % | Valid N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician characteristics | |||

| Age | 147 | ||

| Less than 30 | 20 | 14 | |

| 30–39 | 56 | 38 | |

| 40–49 | 36 | 24 | |

| 50+ | 35 | 24 | |

| Gender identity | |||

| Female* | 125 | 85 | 148 |

| Male | 22 | 15 | |

| Transgender/gender non-binary | 1 | 0.67 | |

| Race | 148 | ||

| Asian | 13 | 9 | |

| Black/African American | 15 | 10 | |

| Mixed race | 10 | 7 | |

| Other | 7 | 5 | |

| White | 103 | 70 | |

| Ethnicity | 148 | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 21 | 14 | |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 127 | 86 | |

| Clinician Training | 148 | ||

| MD and DO | 67 | 45 | |

| APPs† | 81 | 55 | |

| Clinician Specialty | 148 | ||

| Women’s Health and Ob/GYN | 28 | 19 | |

| Family Medicine | 103 | 70 | |

| Internal Medicine, Pediatric/Adolescent Medicine, and ‘other’ | 17 | 11 | |

| Region | 148 | ||

| Northeast | 93 | 63 | |

| South | 28 | 19 | |

| West & Midwest | 26 | 18 | |

| Non-responders | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Current number of cervical cancer screenings performed per month | |||

| 1–10 | 90 | 61 | |

| 11–20 | 27 | 18 | |

| >20 | 31 | 21 | |

| Pap/HPV co-testing as screening method for patients aged 30–65 | 147 ‡ | 99 | 148 |

| Respondent determines management following abnormal results (yes) | 138 | 93 | 148 |

| Health center provides colposcopy on site (yes) | 115 | 78 | 148 |

| Health center provides treatment (LEEP) on site (yes) | 46 | 31 | 148 |

| PANDEMIC IMPACT ON SCREENING AND MANAGEMENT | |||

| Screening in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic (less) § | 127 | 95 | 134 |

| Screening services stopped at any time during the pandemic (yes) § | 66 | 53 | 125 |

| Colposcopy services stopped at any time during the pandemic (yes) §, ¶ | 36 | 31 | 115 |

| LEEP services stopped at any time during the pandemic (yes) §, ¶ | 8 | 17 | 46 |

| Screening in 2021/now compared to pre-pandemic § | 140 | ||

| Less | 39 | 28 | |

| Same | 65 | 46 | |

| More | 36 | 26 | |

-

*for all percentages included in all tables, when percentages were .6-.9, we rounded up to the next whole number.

-

*

Due to small numbers, transgender/non-binary/other were unable to be analyzed as their own category. They were assigned to female for regression analyses because female was the most common response. No difference was noted when grouped with male.

-

†

APPs included: NPs (52), CNMs (7), PAs (17), and other (5).

-

‡

The remaining respondent used primary HPV testing. No respondents in this sample used cytology alone.

-

§

Participants who selected ‘unsure’ were excluded from the denominator. 14 (9%) participants were unsure whether screening was less in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic, 23 (16%) were unsure whether screening services were stopped at any time, 53 participants (36%) were unsure whether colposcopy practices were stopped, 21 (14%) were unsure whether LEEP services were stopped, and 8 (5%) were unsure whether they were screening more or less in 2021/now compared to pre-pandemic.

-

¶

Participants who did not indicate that they performed colposcopy and LEEP services on site were excluded from the demonimator.

Cervical cancer screenings performed monthly by clinician specialty and clinician training.

| 1–5 patients per monthN=47 | 6–10 patients per monthN=43 | 11–20 patients per monthN=27 | >20 patients per monthN=31 | TotalN=148 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician Training | |||||

| MD/DO | 25 (37%) | 20 (30%) | 10 (15%) | 12 (18%) | 67 |

| APPs | 22 (27%) | 23 (28%) | 17 (21%) | 19 (23%) | 81 |

| Clinician Specialty | |||||

| OBGYN/Women’s Health | 2 (7%) | 4 (14%) | 6 (21%) | 17 (59%) | 29 |

| Family Medicine | 39 (38%) | 34 (33%) | 19 (18%) | 11 (11%) | 103 |

| IM, Peds/Adol. Med. | 6 (38%) | 5 (31%) | 2 (13%) | 3 (19%) | 16 |

-

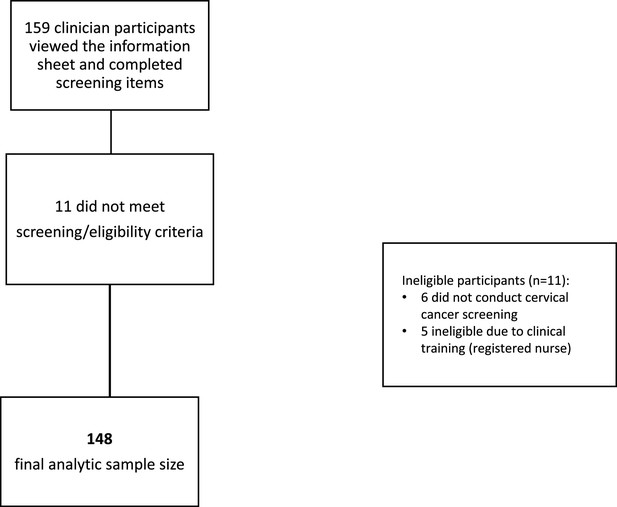

Placeholder for Figure 1*Study flow chart depicting participant exclusions and final analytic sample.

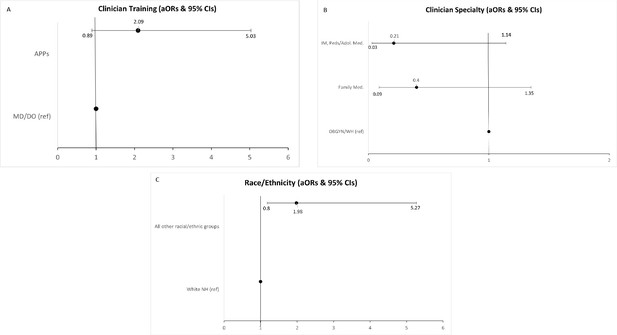

Final model of clinician and practice characteristics associated with odds of reporting conducting the same amount or more cervical cancer screening now/in 2021 than before the COVID-19 pandemic (N=140).

Manual forwards selection was utilized and the following variables were not selected for the final model (p>0.10): (1) region (2) gender and (3) age.

| Overall p | B | SE | Adjusted odds ratio | p | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician training | 0.0605 | |||||

| APPs | 0.7676 | 0.4089 | 2.155 | 0.0605 | 0.967–4.802 | |

| MD/DO | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Clinician specialty | 0.0364 | |||||

| Family Medicine | –1.2214 | 0.6594 | 0.295 | 0.0640 | 0.081–1.07 | |

| Int. Med., Peds/Adol. Med. | –2.0996 | 0.8159 | 0.123 | 0.0101 | 0.025-.606 | |

| Women’s Health/OBGYN | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Clinician race/ethnicity | 0.0873 | |||||

| All other races/ethnicities | 0.7694 | 0.4500 | 2.1159 | 0.0873 | 0.894–5.214 | |

| White non-Hispanic | - | - | - | - | - |

-

*CI reported is for OR.

-

*Placeholder for Figure 2* Forest plots depicting clinician and practice characteristics associated with odds of reporting conducting the same or more cervical cancer screening now/in 2021 vs. before the pandemic.

Barriers to cervical cancer screening and strategies for tracking patients.

| BARRIERS | Rarelyn (%) | Sometimesn (%) | Oftenn (%) | Unsuren (%) | Valid N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systems barriers | 148 | ||||

| Limited in-person appointment availability at our health center | 24 (16) | 53 (36) | 66 (45) | 5 (3) | |

| Patients not scheduling appointments | 5 (3) | 50 (34) | 85 (57) | 8 (6) | |

| Patients not attending appointments (no shows) | 8 (6) | 73 (49) | 62 (42) | 5 (3) | |

| Patient lack of health insurance or limited coverage* | 83 (56) | 36 (24) | 18 (12) | 11 (8) | |

| Inability to track patients who are due for screening | 58 (39) | 46 (31) | 32 (22) | 12 (8) | |

| Health center (or providers) not prioritizing screening due to need to address more acute health problems | 34 (23) | 61 (41) | 46 (31) | 7 (5) | |

| Switched to telemedicine visits so screening not available | 34 (23) | 59 (40) | 48 (33) | 6 (4) | |

| Staffing barriers | Frequency | Percent | 148 | ||

| COVID-related staffing changes impacted ability to screen or track abnormal results (yes) | 67 | 45 | |||

| Current health center staffing compared to pre-pandemic | Decreased n (%) | Stayed the same n (%) | Increased n (%) | Unsure n (%) | 148 |

| Physician (MD, DO) | 52 (35) | 80 (54) | 6 (4) | 10 (7) | |

| Nurse practitioner, Physician Assistant, Certified Nurse Midwife, other Advanced Practice Provider | 42 (28) | 71 (48) | 22 (15) | 13 (9) | |

| Nurse (RN, LPN) | 42 (28) | 71 (48) | 22 (15) | 13 (9) | |

| Medical Assistant | 83 (56) | 45 (30) | 8 (6) | 12 (8) | |

| Office Staff | 64 (43) | 64 (43) | 6 (4) | 14 (10) | |

-

*

Participants were also asked what proportion of patients were unable to obtain treatment (LEEP) due to financial issues, 70% (n=102) answered 0–20%.

Strategies for tracking patients and catching up on missed screenings*.

| STRATEGIES | Frequency | Percent | Valid N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policies or plans for catching up on screenings that were missed due to the pandemic | 148 | ||

| Patients seen via telemedicine are scheduled for future screening visits | 110 | 74 | |

| Electronic medical record is queried to identify patients who are overdue | 92 | 62 | |

| Added dedicated cervical cancer screening days/hours | 32 | 22 | |

| Try to perform cervical cancer screening at acute problem visits/take advantage of opportunities to screen during unrelated visits | 90 | 61 | |

| System for tracking patients overdue for screening | 148 | ||

| No, unaware of any system | 29 | 20 | |

| Paper log of patients | 5 | 3 | |

| Each dept. has its own system | 5 | 3 | |

| Electronic medical record tracker | 94 | 63 | |

| Dedicated staff person/team member to review records and contact patients | 37 | 25 | |

| Other | 16 | 11 | |

| System for tracking abnormal results (e.g., colposcopy referrals) | 148 | ||

| Paper log of patients | 8 | 5 | |

| Each dept. has its own system | 7 | 5 | |

| I am not aware of any system/each provider tracks own results | 56 | 38 | |

| Electronic medical record tracker | 50 | 34 | |

| Dedicated staff person to review records and contact patients | 53 | 36 | |

| Other | 16 | 11 |

-

Note, participants were asked to check all that apply therefore answers sum to >100%.

HPV self-sampling perceptions and practices.

| Frequency | % | Valid N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helpfulness of HPV self-sampling to catch up patients overdue for screening due to COVID-19 pandemic | 147 | ||||

| Not helpful | 12 | 8 | |||

| Somewhat helpful | 89 | 61 | |||

| Very helpful | 46 | 31 | |||

| Would recommend HPV self-sampling instead of clinician-collected sample for cervical cancer screening | 148 | ||||

| All patients | 9 | 6 | |||

| Any patient who preferred a self-sample over a clinician-collected sample | 52 | 35 | |||

| Only pts. who couldn’t have screening in clinic because of transportation issues, fear of coming to clinic, difficulty with speculum exams | 72 | 49 | |||

| N/A I would not offer HPV self-sampling | 8 | 5 | |||

| Other | 7 | 5 | |||

| Location to perform self-sample HPV tests | 148 | ||||

| In clinic | 8 | 6 | |||

| At home | 9 | 6 | |||

| Either in clinic or home, depending on pt. preference | 120 | 86 | |||

| Other | 3 | 2 | |||

| Benefits/advantages of self-sampled HPV testing | Not a benefit n (%) | Small benefit n (%) | Moderate benefit n (%) | Large benefit n (%) | 147 |

| Screen patients who have difficulty accessing screening due to lack of qualified providers, distance to clinic, or logistical barriers (e.g., childcare or work schedules) | 7 (5) | 32 (22) | 50 (34) | 58 (39) | |

| Screen patients via telemedicine | 10 (7) | 50 (34) | 44 (30) | 43 (29) | |

| Screen patients who would prefer not to have speculum exams (e.g. mobility issues or history of trauma) | 3 (2) | 23 (16) | 38 (26) | 83 (56) | |

| Concerns about self-sampled HPV testing | Not a concern | Small concern | Moder-ate concern | Large concern | 147 |

| A pelvic exam by a clinician should be part of cervical cancer screening | 20 (13) | 57 (39) | 38 (26) | 32 (22) | |

| Patients may not collect adequate specimens | 4 (3) | 45 (31) | 49 (33) | 49 (33) | |

| Patient may not return specimen in a timely manner | 3 (2) | 37 (25) | 51 (35) | 56 (38) | |

| If performed at home, patients may not present for routine primary care or follow-up for abnormal test results | 13 (9) | 39 (27) | 49 (33) | 46 (31) |

Qualitative themes with exemplar quotes.

| Theme | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|

| Initial pandemic-associated barriers | “I would say it definitely disrupted all the cancer screenings, the mammo[gram]’s, the colonoscopies, the pap smears, I would say for the whole year of 2020 into about March of 2021.” (APP, Family Medicine) “We were only doing acute visits… everything else was by phone.” (MD, Family Medicine) |

| Ongoing barriers (system and staffing) | System-related: “We have the EMR triggering, and we have active tracking of abnormal Paps. But as far as getting people in for their routine screening, I don't believe we have someone actively tracking that. I feel like it’s more on the provider picking it up as they open the chart.” (APP, Family Medicine) Staffing-related: “We are still working with reduced staff in the office. So, there are definitely still much fewer appointments available.” (APP, Family Medicine) “We realized … we really need to start doing colposcopy again. But unfortunately, that’s also when our physician colposcopy provider left.” (MD/DO, Family Medicine) “Rates of burnout, and then the competition from other systems, hiring people away was pretty debilitating at times.” (APP, Family Medicine) |

| Facilitators and strategies for catching up on cervical cancer screening | Staffing and tracking: “Patients get reminders… the health center as a whole has been trying to run lists of people that are due and bring them in.” (APP, Family Medicine) “If they had an abnormal PAP, the nursing staff would have ticklers [in the EMR] created as a reminder that it’s time for the patient to have a PAP… We have two nurses who are dedicated not for just PAP tracking but for general ticklers.” (MD/DO, Internal Medicine). HPV self-sampling benefits: “It decreases any concerns for like privacy, for discomfort, you know, patients who have trauma histories, maybe patients who are transgender, patients who, you know, like I said, work schedules don't allow them to get in on time, um, it just opens up a way for them to still all be screened in a way that can hopefully feel comfortable and accessible.” (APP, OBGYN/Women’s Health) “I think it could be [useful to address pandemic-related screening deficits]. Especially if we don't have, um, as many in-person appointments available.” (APP, Family Medicine) HPV self-sampling concerns: Inadequate sample: “Making sure that people you know, kind of collect it correctly, mostly just because in my experience, people have not great knowledge about their own anatomy sometimes… if somebody accidentally puts the swab in their rectum, instead of the vagina, you would probably get an HPV result, because you can do HPV testing in the rectum, but you're not getting a, a cervical cancer screening.” (APP, OBGYN/Women’s Health) Kits will not be returned: “We do our –occult blood sampling with home tests, and sometimes –many times, those kits go home and never come back. We're always chasing a patient to kind of get them to bring it back or mail it back.” (APP, Family Medicine) |