SPARK regulates AGC kinases central to the Toxoplasma gondii asexual cycle

eLife assessment

This fundamental study identifies protein kinases in the parasitic protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii that are required for parasite invasion of host cells and differentiation to drug-resistant chronic stages. The use of advanced proteomic and functional approaches provides compelling evidence for the proposed signalling pathway, although additional analyses are needed to fully validate some findings. The work will be of broad interest to cell biologists and parasitologists with an interest in cell signalling and environmental sensing.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.93877.3.sa0Fundamental: Findings that substantially advance our understanding of major research questions

- Landmark

- Fundamental

- Important

- Valuable

- Useful

Compelling: Evidence that features methods, data and analyses more rigorous than the current state-of-the-art

- Exceptional

- Compelling

- Convincing

- Solid

- Incomplete

- Inadequate

During the peer-review process the editor and reviewers write an eLife Assessment that summarises the significance of the findings reported in the article (on a scale ranging from landmark to useful) and the strength of the evidence (on a scale ranging from exceptional to inadequate). Learn more about eLife Assessments

Abstract

Apicomplexan parasites balance proliferation, persistence, and spread in their metazoan hosts. AGC kinases, such as PKG, PKA, and the PDK1 ortholog SPARK, integrate environmental signals to toggle parasites between replicative and motile life stages. Recent studies have cataloged pathways downstream of apicomplexan PKG and PKA; however, less is known about the global integration of AGC kinase signaling cascades. Here, conditional genetics coupled to unbiased proteomics demonstrates that SPARK complexes with an elongin-like protein to regulate the stability of PKA and PKG in the model apicomplexan Toxoplasma gondii. Defects attributed to SPARK depletion develop after PKG and PKA are down-regulated. Parasites lacking SPARK differentiate into the chronic form of infection, which may arise from reduced activity of a coccidian-specific PKA ortholog. This work delineates the signaling topology of AGC kinases that together control transitions within the asexual cycle of this important family of parasites.

Introduction

Apicomplexans parasitize a majority of warm-blooded species, including an estimated quarter of the human population (Jones et al., 2014). Central to parasite success is the ability to transition between different life cycle stages to balance proliferation and transmission (Lourido, 2019). The acute phase of infection by Toxoplasma gondii, a model apicomplexan, induces the pathology of disease. Parasites invade host cells, establish an intracellular niche that subverts innate immune responses, replicate, and exit the host via lysis to establish new sites of infection (Blader et al., 2015). These pathogens adapt to the inverted ion and nutrient gradients within and without the host cell in minutes. Such rapid changes in cellular state depend on signal transduction in T. gondii and related apicomplexans. Second messenger cascades within the parasite cytoplasm are especially well-suited to rapidly transduce and amplify signals from a changing environment. Accordingly, apicomplexans—and T. gondii in particular—have a complete repertoire of second messenger signaling components, from kinases to cyclases and phosphodiesterases (Brown et al., 2020; Pace et al., 2020).

The roles of second messenger kinases—collectively referred to as AGC kinases for the founding members protein kinases A, G, and C—in apicomplexan life cycles have been elaborated in candidate-by-candidate approaches. cGMP-dependent protein kinase (or protein kinase G, PKG) is necessary for the secretion of parasite-specific adhesins and perforins, enabling efficient escape and invasion of host cells (Brown et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2016; Wiersma et al., 2004). In apicomplexan cells, PKG operates upstream of calcium release and thus potentiates an orthogonal second messenger signaling network. Consequently, PKG inhibitors have been pursued as anti-parasitic compounds (Baker et al., 2017; Donald et al., 2006; Sidik et al., 2016a). Another cyclic-nucleotide-dependent protein kinase, PKA, similarly promotes parasite spread during infection; in Plasmodium spp. merozoites, PKA function enables parasite invasion of host cells (Flueck et al., 2019; Patel et al., 2019; Wilde et al., 2019), and in T. gondii balanced PKA C1 function is required to ensure that parasites do not exit the host cell prematurely (Jia et al., 2017; Uboldi et al., 2018). T. gondii has an additional ortholog of the PKA catalytic subunit, PKA C3, which maintains parasites in the acute phase of the infection and reduces conversion to a slowly proliferating, chronic infection termed the bradyzoite stage (Sugi et al., 2016).

Several recent studies have sought to characterize the downstream targets of second messenger kinases in apicomplexans, including PKA, PKG, and calcium-dependent protein kinases (Alam et al., 2015; Balestra et al., 2021; Brochet et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2023; Herneisen et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2017; Nofal et al., 2022). The second messenger networks in these parasites are intricately interwoven, with documented crosstalk between parasite cAMP, cGMP, and calcium signaling cascades. Comparatively little work has addressed upstream signal integration in apicomplexans. In metazoans, growth factor kinases such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) prime numerous AGC kinases for further second messenger-based activation (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012; Mora et al., 2004).

We recently identified the Store Potentiating/Activating Regulatory Kinase (SPARK), an apicomplexan ortholog of metazoan PDK1, as a fitness-conferring candidate in pooled screens of the T. gondii kinome. Parasites depleted of SPARK for multiple replication cycles failed to enter and exit host cells upon stimulation with zaprinast, a chemical that elevates cGMP in parasites (Smith et al., 2022). The Plasmodium falciparum ortholog of SPARK has been implicated in invasion and proliferation through the regulation of the PKA pathway (Hitz et al., 2021). Although parasites with disrupted SPARK alleles were characterized phenotypically, evidence for the PDK1 activity of SPARK was indirect. Here, we map the topology of the signaling network regulated by SPARK in T. gondii. SPARK complexes with an elongin-like protein we name SPARKEL. Phenotypic and proteomic experiments show that SPARK dysregulation lessens PKA C1, PKG, and PKA C3 function. Phenotypes attributed to SPARK depletion—reduced invasion, host cell lysis, calcium signaling, and increased differentiation—can be explained by the attenuated activities of SPARK’s client kinases. The proper functioning of SPARK thus ensures that T. gondii progresses through the acute stage of its infection cycle.

Results

SPARK complexes with an elongin-like protein, SPARKEL

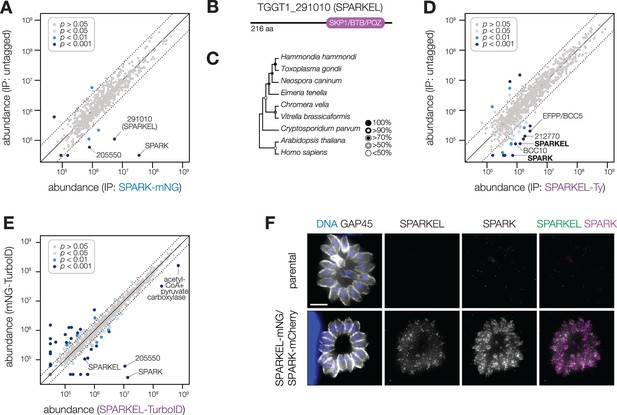

To identify proteins interacting with SPARK, we immunopurified the mNG epitope of the previously described SPARK-mNG-AID strain (Smith et al., 2022) with anti-mNG nanobodies and quantified protein abundance using label-free quantitative proteomics (Figure 1—figure supplement 1 and Supplementary file 1). The immunoprecipitation (IP) successfully enriched SPARK as well as a hypothetical protein, TGGT1_291010. IPs with lysates of parasites expressing SPARK-mNG lacking AID demonstrated that the interaction was not due to the presence of the degron; TGGT1_291010 was once again highly enriched (Figure 1A), along with a putative AGC kinase (TGGT1_205550). The AGC kinase is restricted to coccidians but is dispensable during acute T. gondii infection (Sidik et al., 2016b); we therefore focused our efforts on the hypothetical protein, which contributes to parasite fitness.

SPARK interacts with an Elongin C-like protein.

(A) Protein abundances from immunopurified SPARK-mNG lysates or an untagged control strain. Dotted lines correspond to one modified z-score. Only proteins quantified by greater than one peptide are shown. Proteins identified in only one IP were assigned a pseudo-abundance of 104.5. (B) TGGT1_291010 SPARK elongin-like protein (SPARKEL) gene model. (C) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of SKP1/BTB/POZ domains of TGGT1_291010 orthologs in apicomplexan species along with human and arabidopsis proteins as outgroups. Bootstrap values determined from 1000 replicates. (D) Protein abundances from immunopurified SPARKEL-Ty lysates or an untagged control strain. Dotted lines correspond to one modified z-score. Only proteins quantified by greater than one peptide are shown. Proteins identified in only one IP were assigned a pseudo-abundance of 104.5. (E) Protein abundances following biotinylation and streptavidin enrichment of samples derived from parasites expressing mNG- or SPARKEL-TurboID fusion constructs. A pseudocount of 104.5 was assigned to proteins identified in only one sample. Point colors correspond to significance thresholds. Dotted lines correspond to one median absolute deviation. (F) Immunofluorescence microscopy of intracellular parasites co-expressing SPARKEL-mNG and SPARK-mCherry. Parasites and nuclei were stained with GAP45 and Hoechst 33342, respectively. Scale bar, 5 µm.

TGGT1_291010 is a 23 kDa protein with a C-terminal SKP1/BTB/POZ domain (Figure 1B, Figure 1—figure supplement 1). This domain shares homology with that seen in metazoan Elongin C. For this reason, we named the gene TGGT1_291010 ‘SPARK Elongin-Like protein’ (SPARKEL, Table 1). SPARKEL homologs are found in the free-living alveolates Vitrella brassicaformis and Chromera velia but are absent in Aconoidasida (Figure 1C), suggesting that the gene was present in the ancestor of apicomplexans but was selectively lost in some lineages. The function of proteins with Elongin C-like domains has not been widely investigated in unicellular eukaryotes.

Proteins discussed in the text.

| Gene ID | Description | Context in text | Modifications | Reference | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGGT1_268210 | AGC kinase | SPARK | Smith et al., 2022 | ||

| TGGT1_291010 | hypothetical protein | SPARKEL | SPARK IP-MS | ||

| TGGT1_205550 | AGC kinase | AGC kinase | SPARK TurboID, SPARKEL TurboID | ||

| TGGT1_310220 | hypothetical protein | BCC10 | Engelberg et al., 2022 | SPARKEL IP-MS | |

| TGGT1_269460 | Ser/Thr phosphatase family protein | EFPP/BCC5 | S550 | Engelberg et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2021; Roumégous et al., 2022 | SPARKEL IP-MS, SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_311360 | protein kinase G AGC kinase family member PKG | PKG | Brown et al., 2017 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_226030 | AGC kinase | PKA C1 | Jia et al., 2017; Uboldi et al., 2018 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_242070 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunit | PKA R | S27 | Jia et al., 2017; Uboldi et al., 2018 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome, PKA C3 depletion proteome |

| TGGT1_270240 | MAG1 protein | MAG1 | S238 | Parmley et al., 1994 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_314250 | bradyzoite rhoptry protein | BRP1 | Schwarz et al., 2005 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, 24 hr PKA C3 depletion proteome | |

| TGGT1_208740 | putative microneme protein | Waldman et al., 2020 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, 24 hr PKA C3 depletion proteome | ||

| TGGT1_264660 | SAG-related sequence SRS44 | CST1 | Tomita et al., 2013 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, PKA C3 depletion transcriptome | |

| TGGT1_312330 | hypothetical protein | CST10 | Tu et al., 2020; Waldman et al., 2020 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, PKA C3 depletion transcriptome | |

| TGGT1_260190 | microneme protein MIC13 | MIC13 | Fritz et al., 2012 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, PKA C3 depletion transcriptome | |

| TGGT1_311100 | zinc finger (CCCH type) motif-containing protein | BFD2 | S183 | Licon et al., 2023 | 24 hr SPARK depletion proteome, 24 hr PKA C3 depletion proteome, PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_266010 | phosphatidylinositol 3- and 4-kinase | PI3/4 K | S1439 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_202550 | NLI interacting factor family phosphatase | CTD3/BCC6 | T384 and T386 | Engelberg et al., 2022 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_224240 | protein phosphatase 2 C domain-containing protein | PPM1 | S557 | Yang and Arrizabalaga, 2017 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_268770 | dual specificity phosphatase, catalytic domain-containing protein | phosphosite down-regulated with SPARK depletion | S11 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_219682 | putative pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase | S633 | Ferrarini et al., 2021 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_225960 | STE kinase | S2905 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | ||

| TGGT1_305860 | calcium-dependent protein kinase 3 | CDPK3 | T40 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_267580 | cyclin2-related protein | S491 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | ||

| TGGT1_204280 | cell-cycle-associated protein kinase DYRK | T642, S645, and S649 | Smith et al., 2022 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_239885 | hypothetical protein | S933 and S936 | Smith et al., 2022 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_267100 | protein phosphatase 2 C domain-containing protein | PPM2B | S/T778-788 | Yang et al., 2019 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_311310 | protein phosphatase 2B catalytic subunit, calcineurin family phosphatse superfamily protein | CnA | S104 | Paul et al., 2015 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_277895 | ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase | UBP1 | S44, S52, S1691, and S1695 | Koreny et al., 2023; Wan et al., 2023 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_294360 | putative ubiquitin specific protease 39 isoform 2 | USP39 | S20 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_226050 | hypothetical protein | RBR E3 ligase | S319 and S322 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_239410 | hypothetical protein | putative CCR4-NOT complex subunit | S80 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_295658 | zinc finger in N-recognin protein | UBR box E3 ligase | S3335 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_295710 | HECT-domain (ubiquitin-transferase) domain-containing protein | HECT E3 | S2166, S4313 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome, PKA R depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_216130 | putative ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 | putative E2 enzyme | S193 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome, PKA R depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_293670 | transcription elongation factor A TFIIS | TFIIS | S356 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_226810 | histone lysine methyltransferase SET1 | SET1 | S1780 and S1781 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_218070 | hypothetical protein | NOC3p | S1343 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_280800 | SWI2/SNF2 SRCAP/Ino80 | TgSRCAP | S635 and S638 | Sullivan et al., 2003 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_306660 | RNA pseudouridine synthase superfamily protein | PUS1 | S506 | Anderson et al., 2009 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_312370 | RNA pseudouridine synthase superfamily protein | PUS protein | S951 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_231970 | pre-mRNA processing splicing factor PRP8 | PRP8 | T820 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_310820 | putative SLU7 splicing factor | SLU7 | S[516-519] | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_267600 | FHA domain-containing protein | a FHA protein | S406 and S413 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_216670 | FUSE-binding protein 2/KH type splicing regulatory protein | KH protein | S8 | PKA R, PKA C3, and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_241170 | hypothetical protein | KH protein | S362, S368, and S665 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_235930 | domain K- type RNA binding proteins family protein | KH protein | S58 and S59 | Farhat et al., 2021 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_227450 | hydrolase, NUDIX family protein | DCP2 homolog | T1982 and S1985 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_260600 | Pumilio-family RNA binding repeat-containing protein | PUF1 | S225 | Joyce et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_246040 | MIF4G domain-containing protein | MIF4G domain protein | S341 and S383 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_249610 | hypothetical protein | CBP80 | S851 and S853 | Gissot et al., 2013 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_317720 | putative eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit 7 | eIF3 | S587 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_231480 | putative GCN1 | GCN1 | S1100 | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_251630 | slc30a2 protein | TgZnT | S448 | Chasen et al., 2019 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_288540 | nucleoside transporter protein | nucleoside transporter | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | ||

| TGGT1_260310 | ATP-binding cassette transporter ABC.B1 | ABC transporter | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | ||

| TGGT1_318710 | ATP-binding cassette sub-family F member 1 | ABC transporter | SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | ||

| TGGT1_280660 | HECT-domain (ubiquitin-transferase) domain-containing protein | putative HECT-domain E3 ubiquitin ligase | S5275 and S5279 | SPARK TurboID, SPARK depletion timecourse phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_286470 | AGC kinase | PKA C3 | Sugi et al., 2016 | SPARK TurboID | |

| TGGT1_218240 | hypothetical protein | IMC25 | S1231 | Wang et al., 2016 | PKA R and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_220900 | hypothetical protein | AC13 | S101, S220, S659 | Back et al., 2023 | PKA R, PKG, PKA C3, and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_225690 | hypothetical protein | CIP1 | S850 and S851 | Long et al., 2017 | PKA R and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_257300 | hypothetical protein | CIP2 | S26 | Long et al., 2017 | PKA R and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_308860 | hypothetical protein | AC3 | S216 | Chen et al., 2015 | PKA R and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_315150 | putative eukaryotic initiation factor-4E | eIF4E | S1231 | PKA R and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_235930 | domain K- type RNA binding proteins family protein | KH protein | S58 and S59 | Farhat et al., 2021 | PKA R and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_251640 | ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme subfamily protein | E2 protein | S23 | PKA R and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_253700 | transporter, major facilitator family protein | MFS transporter | S144, S1287, S1288 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_312100 | plasma membrane-type Ca(2+)-ATPase A1 PMCAA1 | TgA1 | S444 and S445 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_314780 | myosin G | MyoG | T1300 | Frénal et al., 2017 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_295360 | hypothetical protein | IMC18 | S159, S161, and S165 | Chen et al., 2015 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_239400 | hypothetical protein | IMC28 | S1081 and S1082 | Chen et al., 2017 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_225560 | hypothetical protein | IMC41 | S440 | Back et al., 2023 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_313480 | hypothetical protein | AAP3 | S178 | Engelberg et al., 2020 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_235380 | hypothetical protein | AC5/TLAP3 | S463 | Chen et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2013 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_263520 | microtubule associated protein SPM1 | SPM1 | S54 and S57 | Tran et al., 2012 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_211710 | TB2/DP1, HVA22 family protein | TB2/DP1, HVA22 family proteins | S155 and S177 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_257040 | TB2/DP1, HVA22 family protein | TB2/DP1, HVA22 family proteins | S32 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_229490 | tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein | TPR protein TGGT1_229490 | S456, S570 and S575 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_246600 | ABC1 family protein | ER ABC transporter | T1278 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_232190 | Sec7 domain-containing protein | Sec7 protein | S180 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_224150 | hypothetical protein | TgCOG6 | T533 and T673 | Marsilia et al., 2023 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_203910 | TBC domain-containing protein | TgTBC10 | T254 and S256 | Quan et al., 2023 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_250870 | DHHC zinc finger domain-containing protein | TgDHHC1 | S345 and S348 | Frénal et al., 2013 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_212820 | ubiquitin family protein | ubiquitin family protein with a C-terminal extension | S368 | PKG and SPARK depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_290970 | 8-amino-7-oxononanoate synthase | TgSPT2 | Nyonda et al., 2022 | PKA C3 depletion transcriptome | |

| TGGT1_259020 | bradyzoite antigen BAG1 | BAG1 | Behnke et al., 2008 | PKA C3 depletion transcriptome | |

| TGGT1_253440 | cell-cycle-associated protein kinase SRPK, putative | SRPK | Talevich et al., 2011 | PKA C3 IP-MS | |

| TGGT1_268960 | putative 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase subunit beta-1 family protein | AMPK subunit beta | Yang et al., 2022 | PKA C3 IP-MS | |

| TGGT1_209985 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase | secreted cAMP-dependent protein kinases | PKA C3 depletion proteome | ||

| TGGT1_356400 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase | secreted cAMP-dependent protein kinases | PKA C3 depletion proteome | ||

| TGGT1_277790 | hypothetical protein | DEP domain protein | S586-600 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_318150 | transporter, major facilitator family protein | TgApiAT3-1 | S54 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion phosphoproteomes | |

| TGGT1_259260 | membrane protein FtsH1 | FtsH1 | S553 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_227280 | dense granule protein GRA3 | GRA3 | S120, T145, S197 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_312420 | hypothetical protein | GRA38 | S457 | Nadipuram et al., 2016 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_204340 | hypothetical protein | CST8 | T601 | Tu et al., 2020 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_230180 | hypothetical protein | GRA24 | T144 | Braun et al., 2013 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_269180 | MIF4G domain-containing protein | eIF4G1 | S1312 | Holmes et al., 2023 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_218300 | zinc finger (CCCH type) motif-containing protein | zinc finger protein | S663 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_209500 | hypothetical protein | DNA repair protein | S619 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_310450 | putative myosin heavy chain | IAP2 | T1269 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_273050 | hypothetical protein | BCC8 | Liang et al., 2021 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_287240 | hypothetical protein | condensin 2 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | ||

| TGGT1_278660 | putative P-type ATPase4 | ATP4 | S83 and T166 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_233130 | nucleoside transporter protein | nucleoside transporter | S6 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_292020 | GCC2 and GCC3 domain-containing protein | CRMPb | S7300, S7303, S7363, and S7365 | Singer et al., 2023; Sparvoli et al., 2022 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_221180 | hypothetical protein | microneme protein | S788 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_304490 | hypothetical protein | microneme protein | S10 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_309590 | rhoptry protein ROP1 | ROP1 | T248 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_211290 | rhoptry protein ROP15 | ROP13 | S312 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_258580 | rhoptry protein ROP17 | ROP17 | T51 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_291960 | rhoptry kinase family protein ROP40 (incomplete catalytic triad) | ROP40 | S98 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_308810 | rhoptry neck protein RON9 | RON9 | S190, S239, S327, and S375 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_310780 | dense granule protein GRA4 | GRA4 | S248 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_275440 | dense granule protein GRA6 | GRA6 | S133 and S134 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_203310 | dense granule protein GRA7 | GRA7 | S62, S72, S77, S135, S153 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_254720 | dense granule protein GRA8 | GRA8 | S198, T202, T262 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_220240 | hypothetical protein | GRA31 | S420 | Nadipuram et al., 2020; Young et al., 2020 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_217680 | hypothetical protein | GRA57 | S806 | Krishnamurthy et al., 2023; Nadipuram et al., 2020; Young et al., 2020 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_215360 | hypothetical protein | GRA62 | S319 | Cygan et al., 2021 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_249990 | hypothetical protein | GRA70 | S436 | Krishnamurthy et al., 2023; Lockyer et al., 2023 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_289540 | hypothetical protein | SFP1 | S897 | Young et al., 2020 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_251740 | AP2 domain transcription factor AP2XII-9 | AP2XII-9 | S1697 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_273870 | SWI2/SNF2 ISWI-like (AT hook) | ISWI protein | T765 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_260240 | hypothetical protein | CAF1 | S272 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_253750 | PLU-1 family protein | PLU-1 | S3874 and S3877 | Wang et al., 2014 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_300330 | hypothetical protein | GCFC | S27 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_223880 | zinc finger, C3HC4 type (RING finger) domain-containing protein | zinc finger protein | S3701 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_288380 | heat shock protein HSP90 | HSP90 | S600 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_321520 | hypothetical protein | p23 | S109 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_225450 | hypothetical protein | CSN3 | S509 and S517 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_242890 | hypothetical protein | PSME4 | S3127 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome | |

| TGGT1_218960 | AP2 domain transcription factor AP2XII-1 | AP2XII-1 | T1697, S1702, T1667, T1703 | Antunes et al., 2024 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_262150 | kelch repeat and K+channel tetramerisation domain containing protein | Kelch13 | S139 | Harding et al., 2020; Koreny et al., 2023; Wan et al., 2023 | PKA C3 depletion phosphoproteome |

| TGGT1_254940 | MIF4G domain-containing protein | eIF4G2 | S985 and S989 | Holmes et al., 2023 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion phosphoproteomes |

| TGGT1_320020 | transporter, major facilitator family protein | TgApiAT2 | S316 and T318 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion phosphoproteomes | |

| TGGT1_233000 | KOW motif domain-containing protein | Spt5 | S1011 and S1014 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion phosphoproteomes | |

| TGGT1_279320 | hypothetical protein | nucleotidyltransferase | S4010 | PKA C3 and SPARK depletion phosphoproteomes | |

| TGGT1_313180 | putative cell-cycle-associated protein kinase PRP4 | PRP4 | S316 | Swale et al., 2022 | |

| TGGT1_214140 | hypothetical protein | associates with AP2IX4/MORC complex | S205 and S212 | ||

| TGGT1_309250 | hypothetical protein | associates with GCN5b complex | PMID: 31381949 and 24391497 |

Immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry of SPARKEL enriched SPARK (Figure 1D and Supplementary file 1) and several putative components of daughter cell replication, including TGGT1_212770 (Dos Santos Pacheco et al., 2021), BCC10, and EFPP/BCC5. To confirm that SPARKEL and SPARK interact in situ, we introduced a C-terminal TurboID fusion at the SPARKEL endogenous locus (Branon et al., 2018). These transgenic parasites were treated with biotin while intracellular, and biotinylated proteins were enriched from lysates via streptavidin affinity purification. As a control, we conducted a parallel experiment with transgenic parasites expressing TurboID fused to a cytosolic mNG fluorophore. SPARK and the AGC kinase TGGT1_205550 were highly enriched in the SPARKEL proximity labeling experiment (Figure 1E and Supplementary file 2). A proximity labeling experiment with parasites expressing TurboID at the N terminus of SPARKEL similarly enriched SPARK and TGGT1_205550 (Figure 1—figure supplement 1 and Supplementary file 2). Thus, the interactions between SPARK, SPARKEL, and TGGT1_205550 were consistently observed across a variety of approaches.

Endogenous tagging of SPARK and SPARKEL in the same parasite strain revealed punctate cytosolic staining for each protein (Figure 1F); however, the low expression level of SPARKEL precluded robust colocalization. Nevertheless, strong mass spectrometry evidence for the physical interaction between SPARK and SPARKEL motivated further analysis of their functional relationship.

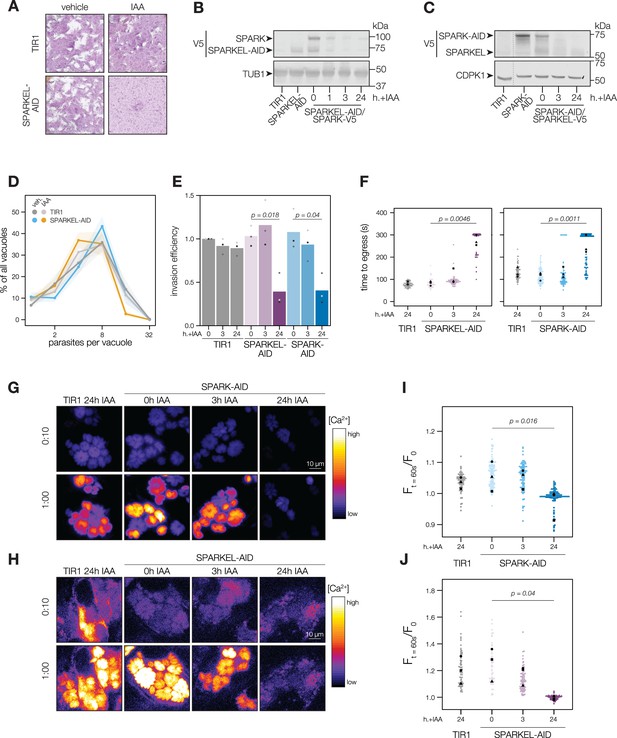

SPARK and SPARKEL depletion phenocopy at multiple steps in the lytic cycle

To determine the regulatory interaction between SPARK and SPARKEL, we first generated a SPARKEL conditional knockdown allele by inserting V5, HaloTag, mini auxin-inducible degron (mAID), and Ty epitopes at the endogenous SPARKEL C terminus. In this strain, we tagged SPARK with a C-terminal V5-mCherry-HA. Parasites treated with auxin (indole-3-acetic acid; IAA) to deplete SPARKEL failed to form plaques in host cell monolayers (Figure 2A). As indicated by immunoblot, IAA treatment led to a reduction in detectable SPARKEL signal within 1 hr, as well as co-depletion of SPARK on a similar time scale (Figure 2B). We next generated a strain expressing SPARK-V5-mAID-HA. Similarly, SPARK levels were reduced within 1 hr of IAA addition (Figure 2—figure supplement 1), as reported for a similar strain previously (Smith et al., 2022). In this genetic background, we tagged SPARKEL endogenously with a C-terminal V5-mNG-Ty. IAA treatment reduced SPARK levels and led to a reduction in SPARKEL abundance (Figure 2C and Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Together, these results suggest that conditional knockdown via the AID system leads to co-depletion of SPARK and SPARKEL. However, SPARK and SPARKEL abundances are low and approach the limit of detection. We could only detect each protein by the V5 epitope. Although our experiments included single-tagged controls, we cannot formally eliminate the possibility that SPARK-AID yields degradation products that run at the expected molecular weight of SPARKEL. More sensitive methods, such as targeted mass spectrometry, may be required to measure the absolute abundance and stoichiometries of SPARK and SPARKEL.

SPARKEL depletion phenocopies the loss of SPARK.

(A) Plaque assays of 500 TIR1 or SPARKEL-AID parasites inoculated onto host cell monolayers and allowed to undergo repeated cycles of invasion, replication, and lysis for 7 days in media with or without 500 µM IAA. (B) Immunoblot of parasites expressing SPARKEL-V5-AID and SPARK-V5 after the indicated h with IAA. TUB1 serves as a loading control. (C) Immunoblot of parasites expressing SPARK-V5-AID and SPARKEL-V5 after the indicated h with IAA. CDPK1 serves as loading control. (D) The number of parasites per vacuole measured for SPARKEL-AID and the parental strain after 24 hr of 500 µM IAA treatment. Mean counts (n=8) are expressed as a percentage of all vacuoles counted. SEM is shown as shaded area. No comparisons yielded significant p-values using ANOVA and Tukey’s test. (E) Invasion assays SPARKEL-AID, SPARK-AID or TIR1 parental strains treated with IAA or vehicle for 3 or 24 hr. Parasites were incubated on host cells for 20 min prior to differential staining of intracellular and extracellular parasites. Parasite numbers were normalized to host cell nuclei for each field. Different shapes correspond to means of n=3 biological replicates. For clarity, only significant comparisons (Welch’s one-sided t-test) are shown. (F) The time to egress of individual intracellular vacuoles following zaprinast treatment. Points correspond to different vacuoles; shapes to different biological replicates (n = 3). Black shapes are the mean for each replicate. p-Values were calculated from a one-tailed t-test. (G, H) Selected frames from live video microscopy of zaprinast-treated SPARK-AID and SPARKEL-AID parasites, respectively, expressing the calcium indicator GCaMP6f, and the corresponding parental strain, 25 hr after infection and with the indicated IAA treatment period. See also Figure 2—video 1 and Figure 2—video 2. (I, J) Relative GCaMP fluorescence of SPARK-AID or SPARKEL-AID vacuoles, respectively, 60 s following zaprinast treatment. Points correspond to different vacuoles; shapes to different biological replicates (n = 3). Black shapes are the mean for each replicate. p-Values were calculated from a one-tailed t-test.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 2B.

V5, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig2-data1-v1.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 2

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 2B.

TUB1, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig2-data2-v1.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 3

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 2C.

V5, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig2-data3-v1.zip

-

Figure 2—source data 4

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 2C.

CDPK1, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig2-data4-v1.zip

To assess the impact of complex knockdown on parasite replication and transitions between intracellular and extracellular environments, we treated SPARKEL-AID and SPARK-AID parasites with IAA, and performed replication, invasion, and egress assays. SPARKEL-AID parasites exhibited normal replication kinetics after 24 hr of IAA treatment (Figure 2D). Invasion and egress efficiency of the AID-tagged strains were reduced after parasites were treated with IAA for 24 hr (Figure 2E and F), as previously reported for SPARK (Smith et al., 2022). Intracellular calcium measurements of GCaMP-expressing parasites revealed a similar trend, with SPARKEL- and SPARK-depleted cells exhibiting reduced calcium mobilization after 24 hr of IAA treatment when stimulated with zaprinast, a compound that stimulates calcium release from parasite intracellular stores (Brown et al., 2016; Sidik et al., 2016a; Figure 2G–H, and Figure 2—figure supplement 1).

SPARK and SPARKEL depletion phenotypes develop over time

SPARK was previously identified in a genetic screen that distinguished acute and delayed death phenotypes in a pooled population of parasites (Smith et al., 2022). As parasites with conditional SPARK alleles were assessed only in the context of delayed death phenotypes—that is, after an entire lytic cycle with IAA treatment—we characterized the ability of SPARK- and SPARKEL-AID parasites to invade and egress after 3 hr of IAA, which is shorter than the T. gondii cell cycle. In marked contrast to the 24-hr-treatment regime, SPARKEL- and SPARK-AID parasites exhibited no deficits in invasion, egress, or calcium mobilization after 3 hr of depletion (Figure 2E–J). Thus, in all assays performed, mutants lacking SPARK and SPARKEL are phenotypically identical, likely due to reciprocal co-depletion, but such phenotypes develop over time.

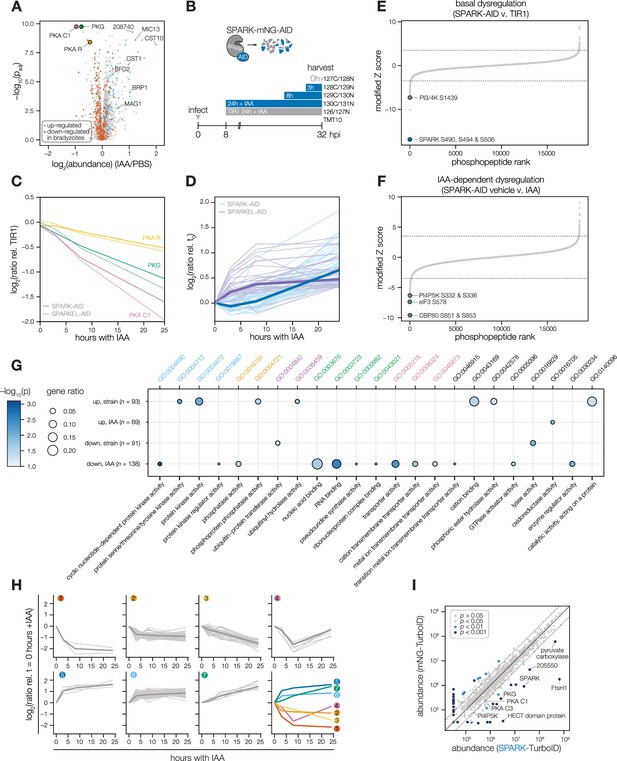

SPARK and SPARKEL depletion leads to AGC kinase down-regulation and up-regulation of bradyzoite-stage proteins

Having verified the interaction between SPARK and SPARKEL, we next investigated pathways regulated by the complex. Initially, we performed a quantitative proteomics experiment following 24 hr of SPARK depletion—the previously described depletion window (Smith et al., 2022). Extended SPARK depletion led to down-regulation of PKG and both the catalytic and regulatory subunits of PKA (Figure 3A and Table 1). We also observed up-regulation of bradyzoite-specific genes upon SPARK depletion (Figure 3A and Table 1), including MAG1, BRP1, TGME49_208740, CST1, CST10, MIC13, and BFD2. We were unable to measure SPARK or SPARKEL abundances in this proteome.

Depletion of SPARK or SPARKEL leads to downregulation of AGC kinases and upregulation of chronic-stage markers.

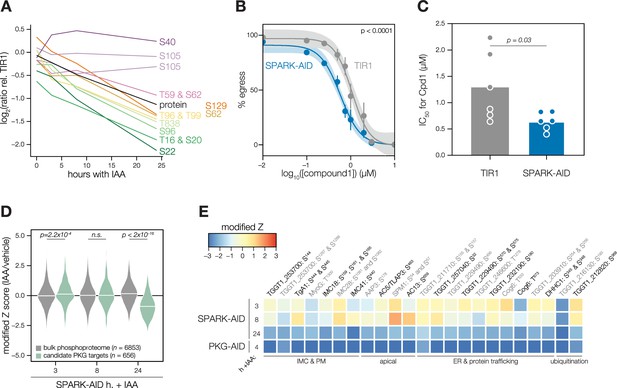

(A) Volcano plot displaying the protein abundance ratios of SPARK-AID parasites treated with IAA or vehicle for 24 hr and adjusted p-values for n = 2 biological replicates. Proteins identified as up- or down-regulated in parasites overexpressing the driver of differentiation (BFD1) (Waldman et al., 2020) are shown in blue and vermilion, respectively. In total, 4474 proteins were quantified, 3847 of which registered more than one peptide. (B) Schematic of the phosphoproteomics experiment following SPARK depletion. Intracellular parasites expressing SPARK-AID were treated with 500 µM IAA for 24, 8, 3, or 0 hr and were harvested at 32 hpi simultaneously with the TIR1 parental strain as a control. Samples were multiplexed with tandem mass tags (TMT). The same experimental design was used for SPARKEL-AID proteomics. Each experiment included two biological replicates. (C) Average protein abundances of PKG, PKA-R, and PKA-C1 relative to the TIR1 parental strain after the indicated period of SPARK (thick lines) or SPARKEL (dotted lines) depletion. (D) Average protein abundances of up-regulated bradyzoite genes relative to the TIR1 parental strain after the indicated period of SPARK (blue lines) or SPARKEL (purple lines) depletion. Up-regulated bradyzoite proteins were defined as those significantly increased in parasites overexpressing BFD1 (Waldman et al., 2020) and two modified Z-scores above the median in the SPARK depletion proteome. Rank-ordered plots of (E) Phosphopeptide basal dysregulation score (peptide abundance in the SPARK-AID strain without IAA treatment relative to the TIR1 parental strain) or (F) IAA-dependent score (summed peptide ratios relative to the SPARK-AID t0 peptide abundance). Dotted lines correspond to 3.5 modified Z scores. Colored points correspond to phosphosites discussed in the main text. (G) Gene ontology (GO) enrichment of phosphoproteins exhibiting SPARK-dependent regulation. Gene ratio is the proportion of proteins with the indicated GO term divided by the total number of proteins. Significance was determined with a hypergeometric test; only GO terms with p<0.05 are shown. Redundant GO terms were removed. Categories discussed in the main text are highlighted with colored text. (H) Gaussian mixture modeling of SPARK-dependent peptides identified by more than one PSM revealed seven kinetically resolved clusters. Individual peptides or the median ratios in each cluster are depicted by light and dark gray lines, respectively. Clusters are numbered according to their discussion in the main text. (I) Protein abundances following biotinylation and streptavidin enrichment of samples derived from parasites expressing mNG- or SPARK-TurboID fusion constructs. A pseudocount of 104.5 was assigned to proteins identified in only one sample. Point colors correspond to significance thresholds for n = 2 biological replicates. Dotted lines correspond to one median absolute deviation.

To determine the critical window of SPARK and SPARKEL function, we performed quantitative proteomics with tandem mass tag multiplexing that included samples with 0, 3, 8, and 24 hr of SPARK or SPARKEL depletion harvested 32 hr post-infection. The experiments included internal TIR1 parental strain controls to account for possible basal downregulation arising from the degron (Figure 3B). We detected 3,333 and 3,880 proteins with quantification values in the SPARK and SPARKEL depletion time courses, respectively (Supplementary file 3). PKA C1, PKA R, and PKG protein abundances only began to drop after 8 hr of IAA treatment (Figure 3C). Globally, these kinase subunits were the most down-regulated proteins following 24 hr of either SPARK or SPARKEL depletion (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Bradyzoite proteins up-regulated upon SPARK depletion primarily increased between 8 and 24 hr of IAA treatment (Figure 3D); the same proteins increased in abundance with 24 hr of SPARKEL depletion (Figure 3D). We were unable to measure SPARK or SPARKEL abundances in either proteome. Nevertheless, depletion of the SPARK-SPARKEL complex consistently leads to up-regulation of proteins associated with the bradyzoite stage of development, as well as down-regulation of PKG and the PKA C1 complex.

A depletion phosphoproteome implicates SPARK in the signaling, gene regulation, and metabolic states of the lytic cycle

To determine SPARK-dependent phosphoregulation, we enriched and analyzed phosphopeptides from the depletion proteome. We identified 18,518 phosphopeptides with quantification values, of which 8867 were measured with more than one peptide-spectrum match (PSM). Principal component analysis (PCA) separated the SPARK-AID samples treated for 24 hr with IAA from all other samples, while closely clustering biological replicates (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Despite the low abundance of SPARK and SPARKEL, individual phosphopeptides were detected for each protein. Likely due to basal degradation, the abundance of the SPARK phosphopeptide was ten-fold lower in SPARK-AID samples compared to the TIR1 control such that further depletion could not be measured (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). The SPARKEL phosphopeptide abundance was also reduced relative to the TIR1 control sample; however, it decreased further between 3 and 8 hr of IAA treatment (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Because no other SPARKEL phosphopeptides were detected, it is not possible to determine whether this decrease is phosphosite-specific or due to a general decrease in SPARKEL protein abundance.

SPARK-regulated phosphopeptides may manifest in a strain-dependent or IAA-dependent manner. To account for basal downregulation, we ranked phosphopeptides by their log2-ratios of altered abundances in the SPARK-AID strain relative to the TIR1 parental strain (Figure 3E). When a cutoff of 3.5 modified Z-scores was used, 91 phosphopeptides (44 with >1 PSMs) and 69 phosphopeptides (19 with >1 PSMs) were down- or up-regulated, respectively. The aforementioned phosphosite belonging to SPARK was the most strongly down-regulated phosphopeptide by this metric. One phosphopeptide belonging to a phosphatidylinositol 3- and 4-kinase (PI3,4K) was also strongly down-regulated (Table 1); however, the protein abundance of this enzyme was not quantified. To identify phosphopeptides most altered by IAA treatment, and hence SPARK depletion, we summed and ranked phosphopeptides by log2-ratios of abundances in the SPARK-AID strain relative to the untreated samples (Figure 3F). By this metric, 138 phosphopeptides (51 with >1 PSMs) and 93 phosphopeptides (36 with >1 PSMs) were down- or up-regulated by more than 3.5 modified Z-scores, respectively. Phosphoproteins belonging to this category are discussed below.

To uncover the molecular pathways regulated by SPARK, we performed enrichment analysis of the phosphopeptides exhibiting the highest degree of altered abundance upon SPARK depletion (Figure 3G). Changes in SPARK function likely alter post-translational modification (PTM) cascades both directly and indirectly. SPARK depletion reduced the abundance of phosphopeptides belonging to cyclic nucleotide-regulated kinases, which was in part driven by a reduction in kinase abundance. SPARK depletion also coincided with a reduction in phosphosites on several phosphatases (Table 1), including BCC6, PPM1, and an uncharacterized dual-specificity phosphatase. By contrast, phosphorylation of other kinases and phosphatases increased upon SPARK depletion, which may arise as an indirect consequence of SPARK function. Upregulated phosphosites were found on pyruvate dehydrogenase and STE kinase, CDPK3, cyclin2-related protein, and the kinases TGGT1_204280 and TGGT1_239885; as well as the protein phosphatases PPM2B, calcineurin, and EFPP. Phosphosites belonging to proteins involved in ubiquitin transfer and hydrolysis also increased in abundance upon SPARK depletion. Examples of this class included UBP1, USP39, an RBR E3 ligase, CCR4-NOT subunit, and UBR box E3 ligase. To a lesser degree, phosphosites on ubiquitin ligases were also down-regulated following SPARK depletion—for example, a HECT E3 and a putative E2 enzyme. Thus, SPARK function has broad implications for PTM cascades.

Additional functional categories enriched for SPARK-dependent regulation included nucleic acid–binding proteins (Figure 3G and Table 1). A number of down-regulated phosphosites belong to proteins involved in DNA accessibility and transcription—for example, TFIIS, SET1, NOC3p, and TgSRCAP. RNA modification enzymes also exhibited phosphoregulation, such as two PUS proteins, PRP8, SLU7, a FHA protein, three KH proteins, and a DCP2 homolog. Other regulated phosphoproteins may function in mRNA cap or untranslated region (UTR) binding, such as TgPUF1, a MIF4G protein, CBP80, eIF3, and GCN1. Some of these proteins have been linked to expression changes during stage conversion, with PUF1 and SRCAP levels having been noted to increase during stress (Joyce et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Sullivan et al., 2003). Moreover, CBP80, eIF3, and the KH protein TGGT1_216670 co-purified with the Alba complex (Gissot et al., 2013), which has been implicated in bradyzoite differentiation. Regulation of these proteins thus may be linked to the elevated expression of bradyzoite-stage proteins upon SPARK depletion.

Several putative transporters also exhibited decreased phosphopeptide abundance upon SPARK knockdown (Figure 3G). Some of these phosphoproteins channel inorganic cations, such as TgZnT (Chasen et al., 2019). Others likely transport small organic molecules—for example, a nucleoside and two ABC transporters. In aggregate, these analyses implicate SPARK in numerous cellular processes, including signaling, gene regulation, and metabolic exchange.

Clustering of phosphopeptide kinetics identifies seven response signatures

We sought to resolve the SPARK phosphoproteome into kinetically distinct clusters. Gaussian mixture-model algorithms heuristically clustered phosphopeptides identified by more than one PSM into seven classes on the basis of their response signatures following SPARK depletion (Figure 3H). Two phosphopeptides in Cluster 1 were distinguished by their rapid and sustained depletion and corresponded to CBP80 and eIF3, both of which function in translation. The second cluster of phosphopeptides was largely down-regulated by 3 hr of IAA treatment and lacked dynamics following this window. PKA and PKG phosphopeptides belonged to Cluster 3, which decreased only after 8 hr of IAA treatment. The final cluster of depleted phosphopeptides, Cluster 4, only exhibits down-regulation at 8 hr of IAA treatment.

Up-regulated phosphopeptides mirrored the dynamics of the down-regulated clusters. Cluster 5 phosphopeptides were elevated within 3 hr of IAA treatment and continued to increase thereafter. Cluster 6 was up-regulated by 3 hr of IAA treatment and was stable thereafter. Cluster 7 increased gradually and predominantly after 8 hr of IAA treatment. Upregulated phosphosites may arise from a number of mechanisms following SPARK depletion. For example, SPARK activity may inhibit downstream kinases or activate downstream phosphatases, sterically block access of serines/threonines to other enzymes, or give rise to crosstalk between PTMs.

Because non-phosphopeptide and phosphopeptide abundances were quantified in different mass spectrometry experiments, it is challenging to compare the rates of phosphopeptide and parent protein abundance changes, especially when phosphorylation status and protein stability are interconnected. In general, both PKA C1, PKA R, and PKG protein and phosphosite abundances decreased following SPARK depletion (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), as discussed below. We also observed down-regulation of phosphopeptide and protein abundances of a MIF4G domain protein. Approaches that take into account subcellular proximity were required to distinguish direct substrates from pathways downstream of SPARK function.

Proximity labeling identifies putative SPARK targets in situ

To gain insight into proximal SPARK interactors in intracellular parasites, we tagged the endogenous C terminus of SPARK with a TurboID domain and carried out proximity labeling experiments, as previously described for SPARKEL. We observed overlap in the phosphoproteomic and proximity labeling experiments. PKG was enriched (Figure 3I and Supplementary file 3), while PKA C1 narrowly missed our cutoffs. A putative HECT E3 ubiquitin ligase (TGGT1_280660) with two phosphosites down-regulated in the SPARK-dependent phosphoproteome was a candidate interactor. We also detected enrichment of PKA C3. PKA C3 is a coccidian-specific ortholog of the apicomplexan PKA catalytic subunit Sugi et al., 2016; however, no PKA C3 phosphopeptides were quantified in our depletion phosphoproteome experiments, likely due to the low abundance of the protein. SPARKEL was not quantified in the proximity labeling experiment, despite prior detection of the reciprocal interaction (Figure 1E). These integrated proteomics approaches hint that the phenotypes associated with SPARK depletion may arise from the altered activity of AGC kinases regulated by SPARK.

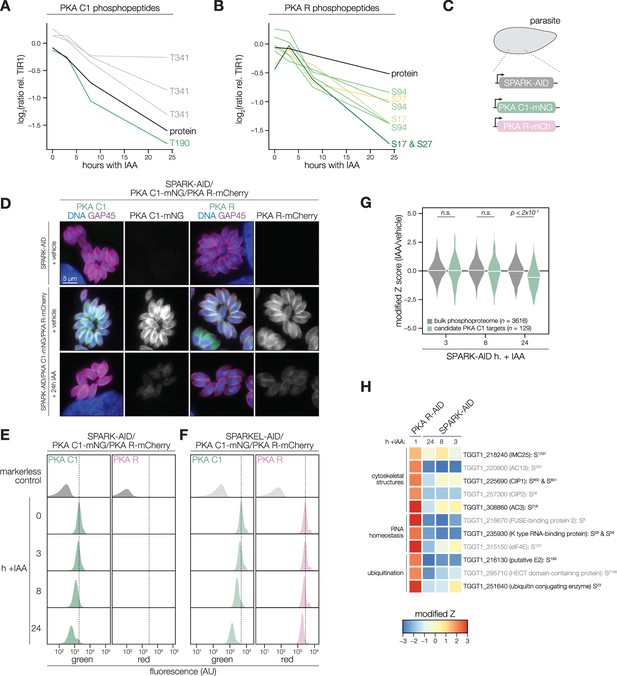

SPARK functionally interacts with PKA and PKG

The SPARK depletion time course phosphoproteome showed a reduction in the abundance of PKA C1 T190 and T341, which are located in the activation loop and C-terminal tail, respectively (Figure 4A). Several phosphosites residing in the N terminus of PKA R (e.g. S17, S27, and S94) also decreased following SPARK depletion (Figure 4B). Transcript levels for PKA C1, and two other AGC kinases tested, remained unchanged following 3 or 24 hr of SPARK depletion (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). To confirm the depletion kinetics of PKA, we tagged the kinase subunits with fluorophores in the SPARK-AID parasite strain (Figure 4C). Prolonged SPARK depletion (24 hr) reduced PKA C1 and PKA R immunofluorescence signals in intracellular parasites (Figure 4D). To monitor kinase levels kinetically, we performed flow cytometry at several time points following the addition of IAA (Figure 4E). PKA C1 and PKA R fluorophore intensity decreased predominantly after 8 hr of IAA treatment, consistent with proteomic results. In parallel experiments, we tagged PKA C1 and PKA R in the SPARKEL-AID strain, revealing a comparable loss of the two markers following SPARKEL depletion (Figure 4F).

PKA C1 levels are down-regulated upon SPARK depletion.

(A–B) Average protein and phosphopeptide abundances of PKA C1 (A) and PKA R (B) following SPARK depletion. (C) Schematic of the genetic strategy used to monitor PKA C1 and PKA R abundances following SPARK (or SPARKEL) down-regulation with IAA. (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy of parasites expressing SPARK-AID, PKA C1-mNG, and PKA R-mCherry after 0 or 24 hr of IAA treatment to degrade SPARK. Parasites and nuclei were stained with GAP45 and Hoechst 33342, respectively. GAP45 staining and mNG or mCherry staining were normalized to vehicle-treated tagged samples. (E, F) Flow cytometry analysis of parasites expressing PKA C1-mNG, PKA R-mCherry, and SPARK-AID or SPARKEL-AID, respectively, after the indicated period of IAA treatment. The dotted line centers the mode of the vehicle-treated sample. Traces were normalized by unit area. (G) Violin plots displaying the distribution of phosphopeptide abundance values following SPARK depletion. The distributions of candidate PKA C1 targets, as defined in the text and methods, are shown in green. The distributions and p-values (KS test) were derived from the overlapping subset of phosphopeptides identified in each dataset. (H) Heat map of the abundance ratios of candidate PKA C1 targets following SPARK depletion. PKA R depletion results in up-regulation of PKA C1, and candidate PKA C1 targets therefore have positive abundance ratios following PKA R down-regulation.

We considered the possibility that the SPARK depletion phosphoproteome represents a convolution of phosphoproteomes arising from broader AGC kinase down-regulation. We systematically tested this possibility by generating phosphoproteomes of parasites depleted of PKA R and PKG (Supplementary file 4). As association with PKA R inhibits PKA C1 activity (Jia et al., 2017), we reasoned that phosphosites up-regulated after a short window of PKA R depletion represent candidate PKA C1 targets. Similarly, phosphosites down-regulated after PKG depletion represent candidate PKG substrates (Brown et al., 2017). Phosphopeptides above two modified Z-scores were considered candidate targets of each kinase.

Compared to the bulk phosphoproteome, the PKA C1-dependent phosphopeptides significantly decreased in abundance between 8 and 24 hr of SPARK depletion (Figure 4G). When we applied the same analysis to a similarly acquired PP1-dependent phosphoproteome (Herneisen et al., 2022), we found no significant relationship to the SPARK phosphoproteome (Figure 4—figure supplement 1), suggesting that the association with PKA C1 is specific. Several of the overlapping SPARK and PKA C1–dependent phosphoproteins localized to the parasite periphery and apex (Figure 4H), for example, IMC25, AC13, CIP1, CIP2, and AC3. Others are putatively involved in RNA-binding functions, such as eIF4E and two KH proteins, including a component of the METTL3/METTL14 core (Farhat et al., 2021). We also observed regulation of phosphoproteins involved in ubiquitin transfer, including the aforementioned E2 and HECT E3 proteins (Table 1). Regulation of these proteins may account for both the kinetic- and replicative-phase phenotypes attributed to perturbed PKA C1 activity (Jia et al., 2017; Uboldi et al., 2018).

We carried out related experiments to validate that SPARK regulates PKG function. The SPARK depletion time course phosphoproteome showed a reduction in the abundance of several phosphosites residing in the N terminus of PKG as well as T838, which corresponds to the activation loop (Figure 5A). By contrast, S105 did not greatly decrease, and S40 abundance increased slightly. Attempts to tag PKG with a fluorophore in a functional SPARK-AID background were unsuccessful. Global genetic screens have indicated that parasites with hypomorphic PKG—as can arise through endogenous tagging—are rapidly outcompeted by wildtype parasites (Fang et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2022). Therefore, we instead relied on chemical-genetic interactions to validate the relationship between PKG and SPARK. We reasoned that parasites with down-regulated PKG activity might be sensitized to the specific PKG inhibitor Compound 1 (Donald et al., 2002). Previous studies had shown that SPARK is dispensable for A23187-induced egress Smith et al., 2022; however, PKG function is required for ionophore-induced egress (Brown et al., 2017; Lourido et al., 2012). We performed egress assays using parasites depleted of SPARK for 24 hr and treated with different concentrations of Compound 1. As anticipated, SPARK depletion sensitized parasites to inhibition with Compound 1, as assessed by A23187-induced egress (Figure 5B–C), suggesting that PKG activity is decreased in the absence of SPARK.

Characterization of PKG function during SPARK depletion.

(A) Protein and phosphopeptide abundances of PKG following SPARK depletion. (B) A23187-stimulated egress assays performed at different concentrations of compound 1 after TIR1 and SPARK-AID parasites had been treated with IAA for 24 hr. Curves were fit to the average values of six replicates and were compared with an extra sum of squares F test. (C) The IC50 values of each strain for compound 1; each point represents a biological replicate (n = 6). Significance was assessed with a two-tailed t-test. (D) Violin plots displaying the distribution of phosphopeptide abundance values following SPARK depletion. The distributions of candidate PKG targets are shown in green. The distributions and p-values (KS test) were derived from the overlapping subset of phosphopeptides identified in each dataset. (E) Heat map of the abundance ratios of candidate PKG targets following SPARK depletion.

As with PKA, we quantified the behavior of putative PKG substrates in the SPARK-AID phosphoproteome. Compared to the bulk phosphoproteome, the PKG-dependent phosphopeptides significantly decreased in abundance between 8 and 24 h of SPARK depletion (Figure 5D). Several overlapping SPARK- and PKG-dependent phosphoproteins localized to the parasite periphery, including an MFS transporter, TgA1, MyoG, IMC18, IMC28, and IMC41. Other PKG/SPARK-dependent sites were found in the apical proteins AAP3, AC5/TLAP3, AC13, and SPM1; while several other proteins localized to the ER, including two TB2/DP1, HVA22 family proteins, a TPR protein, and an ABC transporter (Figure 5E). Others function in the secretory or protein trafficking pathways, such as Sec7, COG6, TgTBC10, and TgDHHC1. We also observed down-regulation of phosphosites belonging to proteins involved in ubiquitin transfer, such as an E2 enzyme and a ubiquitin family protein with a C-terminal extension. The precise pathways regulated by TgPKG remain to be defined; however, recent studies triggering PKG activity in T. gondii (Chan et al., 2023; Herneisen et al., 2022) or related Plasmodium spp. (Alam et al., 2015; Balestra et al., 2021; Brochet et al., 2014) suggest that PKG substrates relevant for egress reside at the parasite periphery and ER, as observed for the overlapping PKG and SPARK targets here.

Depletion of SPARK, SPARKEL, or PKA C3 promotes chronic differentiation

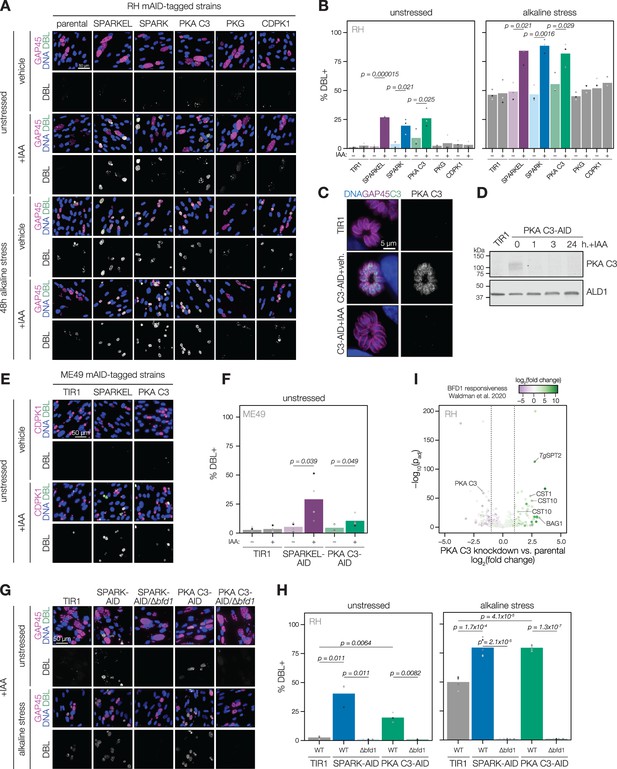

Several pieces of evidence suggested that SPARK and SPARKEL depletion may prompt differentiation from the tachyzoite to bradyzoite state through dysregulation of another AGC kinase, PKA C3. First, down-regulation of SPARK and SPARKEL coincided with up-regulation of bradyzoite markers (Figure 3A and D). Second, SPARK proximity labeling resulted in enrichment of PKA C3 (Figure 3I)—a negative regulator of the bradyzoite stage (Sugi et al., 2016) and, to date, the only AGC kinase characterized with a function in differentiation (Augusto et al., 2021). Prolonged SPARK and SPARKEL depletion indeed elevated differentiation under normal culture conditions, as measured by staining of the cyst walls with dolichos binding lectin, a characteristic of chronic-stage bradyzoite vacuoles (Figure 6A–B). N-terminal tagging of SPARKEL with AID similarly elevated differentiation upon IAA treatment (Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Alkaline media in combination with serum starvation and low carbon dioxide is commonly used to induce bradyzoite transformation in cell culture. SPARK and SPARKEL down-regulation enhanced differentiation under such conditions (Figure 6A–B).

SPARK, SPARKEL, and PKA C3 are negative regulators of differentiation.

(A) Immunofluorescence differentiation assays following knockdown of the indicated AID strains for 48 hr under standard growth conditions (unstressed) or alkaline stress. GAP45 was used to stain parasite vacuoles. Differentiated vacuoles were stained with biotinylated DBA/streptavidin-APC. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst. (B) Quantification of the number of DBL +vacuoles expressed as a percentage of the total stained vacuoles is shown for parasites grown under unstressed or stressed conditions. One-sided t-test, n=3 biological replicates. (C) Fixed, intracellular PKA C3-mNG-AID parasites visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy using the mNG epitope after 1 hr of vehicle or IAA treatment. The mNG signal was internally normalized to the TIR1 parental strain. (D) Immunoblot of PKA C3-AID parasites following the addition of vehicle or 500 µM IAA for 1, 3, or 24 hr. TIR1 was included as an untagged control. PKA C3-AID was detected with V5, and ALD1 was probed as a loading control. (E) Immunofluorescence differentiation assays following knockdown of the indicated ME49/AID-tagged strains under unstressed conditions for 48 hr. Staining was performed as described above, except CDPK1 was used as a parasite vacuole marker. (F) Quantification of the number of DBL +vacuoles expressed as a percentage of the total stained vacuoles in (E). Two-sided t-test, n=5 biological replicates. (G) Immunofluorescence differentiation assays of parasite strains with or without BFD1, depleted of PKA C3 or SPARK with 500 µM IAA and grown under unstressed conditions or alkaline stress for 48 hr. (H) The percentage of DBL +vacuoles corresponding to (G). One-sided t-test. Three biological replicates were quantified under unstressed conditions; five replicates were performed under alkaline stress (I) Effects of 24 hr of PKA C3 knockdown on the transcriptome relative to the untagged strain. Dotted lines correspond to an absolute log2 change of 1. Genes significantly affected by BFD1 overexpression p-value <0.001 as previously defined (Waldman et al., 2020) are colored according to log2 change in the chronic-stage transcriptome. Highlighted points are discussed in the text. P-values were determined from a Wald test implemented in DESeq2.

-

Figure 6—source data 1

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 6D.V5, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig6-data1-v1.zip

-

Figure 6—source data 2

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 6D.

ALD1, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig6-data2-v1.zip

To dissect the hypothesized PKA C3–dependent arm of SPARK regulation, we altered the PKA C3 genomic locus with a V5-mAID-mNG-Ty tagging payload. Addition of IAA to the culture medium resulted in down-regulation of PKA C3 levels to below the detection limit within one hour (Figure 6C–D). PKA C3 exhibited low expression levels in cytoplasmic puncta (Figure 6C), as previously reported (Sugi et al., 2016). We confirmed that prolonged PKA C3 depletion led to elevated differentiation rates under normal and alkaline-stress culture conditions (Figure 6A–B) and observed that the effect was similar to SPARK or SPARKEL knock-down. Given that SPARK also regulates PKG and PKA C1, we considered the possibility that differentiation may be linked to a block in motility. However, the inability to egress is not sufficient for differentiation, as conditional knockdown of PKG or CDPK1 (Brown et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2023; Shortt et al., 2023) did not enhance the frequency of differentiation markers (Figure 6A–B). We did not assess differentiation in PKA C1 knockdown parasites, as these mutants spontaneously egress from host cells (Jia et al., 2017; Uboldi et al., 2018).

The RH strain in which we generated mutants is reported to be refractory to differentiation into the bradyzoite form (Dubey et al., 1999), likely due to defects downstream of the pathways that lead to the initial synthesis of the cyst wall. We generated SPARKEL- and PKA C3-AID strains in the ME49 background (Figure 6—figure supplement 1), which readily undergoes differentiation in tissue culture and mice, and confirmed that depletion of either prompts spontaneous differentiation in tissue culture (Figure 6E–F). We did not assess alkaline-induced differentiation, as this stress treatment results in near-complete differentiation in the ME49 strain (Waldman et al., 2020), which complicates measurement of enhanced differentiation.

To assess whether excess differentiation caused by SPARK and PKA C3 depletion is dependent on a previously characterized transcriptional regulator of differentiation, BFD1 (Waldman et al., 2020), we replaced the BFD1 CDS with a sortable dTomato cassette in the SPARK- and PKA C3-AID strains (Figure 6—figure supplement 1). The resulting SPARK- and PKA C3-AID/∆bfd1 mutants failed to undergo differentiation as measured by cyst wall staining (Figure 6G–H), suggesting that differentiation caused by depletion of these kinases depends on the BFD1 circuit. We additionally profiled transcriptomic remodeling in PKA C3-AID parasites that had been depleted of the kinase for 24 hr and compared these changes to the chronic-stage transcriptome of parasites overexpressing BFD1 (Waldman et al., 2020). We observed up-regulation of several chronic-stage proteins upon PKA C3 depletion (Figure 6I), including BAG1, CST1, CST10, MIC13, and TgSPT2 (Licon et al., 2023). PKA C3 mRNA abundance was down-regulated, suggesting that tagging may alter steady-state transcript levels. Together, these results suggest that the bradyzoite stage conversion induced by knockdown of PKA C3 and SPARK proceeds through the canonical transcriptional pathway.

PKA C3 interacts with the SPARK complex

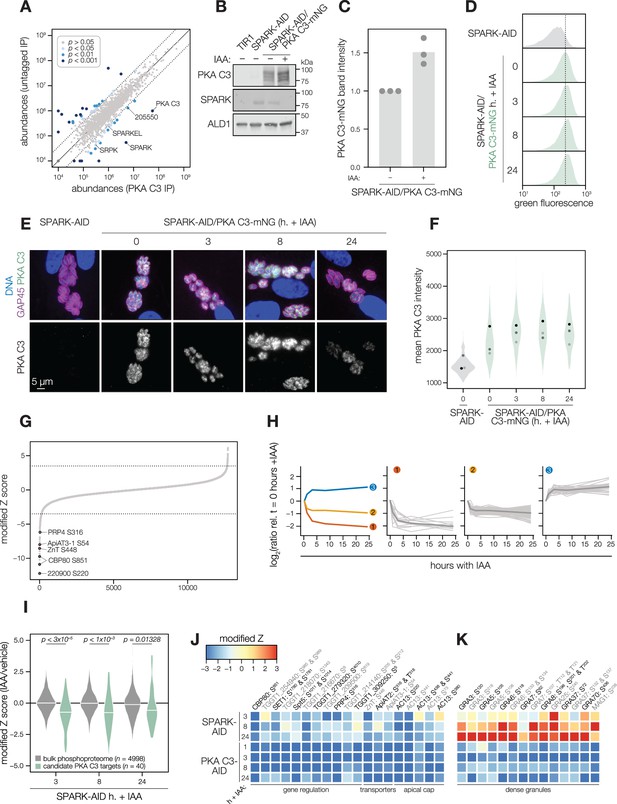

Several AGC kinases, including PKA C3, share the activation loop motif TLC/VGTxxY, which displayed SPARK-dependent phosphorylation in PKA C1 and PKG. PKA C3 was not detected in our SPARK depletion proteomics experiments (Figure 3). To determine whether SPARK and PKA C3 interact, we immunopurified PKA C3 lysates, using the mNG epitope as a handle. The immunoprecipitated PKA C3 was highly enriched for SPARK (Figure 7A), and to a lesser extent, other protein kinases including TGGT1_205550, SRPK, and AMPK subunit beta. The latter has recently been characterized as a key metabolic regulator that enhances differentiation when knocked out (Yang et al., 2022). To a lesser extent, SPARKEL was also significantly co-purified with PKA C3 (Supplementary file 1). Our results are consistent with other reports that PKA C3 does not interact with the canonical PKA regulatory subunit in T. gondii (Jia et al., 2017; Uboldi et al., 2018) and, in conjunction with TurboID data presented in Figure 3I, provide support for a strong physical interaction between SPARK and PKA C3.

SPARK and PKA C3 physically and genetically interact.

(A) Protein abundances from immunopurified PKA C3-mNG-AID lysates or an untagged control strain from n = 2 biological replicates. Dotted lines correspond to one modified z-score. Only proteins quantified by greater than one peptide are shown. Proteins identified in only one IP were assigned a pseudo-abundance of 104.5. Point colors correspond to significance thresholds. (B) Immunoblot of parasites expressing SPARK-V5-AID-HA and PKA C3-mNG after 24 hr of IAA treatment. ALD1 serves as a loading control. Band intensity normalized to the dual-tagged strain is shown in (C) from three replicates. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of SPARK-AID parasites expressing PKA C3-mNG treated with IAA for the indicated number of h. Traces are representative of two biological replicates. The dotted line centers the mode of the vehicle-treated sample. Traces were normalized by unit area. (E–F) Fixed, intracellular SPARK-AID/PKA C3-mNG parasites visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy using the mNG epitope after the indicated period of IAA treatment (E). The mNG signal was internally normalized to the SPARK-AID parental strain. Quantification of the PKA C3 signal intensity of three replicates is shown in (F). (G) Phosphopeptide IAA-dependent score (summed peptide ratios relative to the PKA C3-AID t0 peptide abundance). Dotted lines correspond to 3.5 modified Z scores. Colored points correspond to phosphosites discussed in the main text. (H) Gaussian mixture modeling of PKA C3-dependent peptides identified by more than one PSM revealed three kinetically resolved clusters. Individual peptides or the median ratios in each cluster are depicted by light and dark gray lines, respectively. Clusters are numbered according to their discussion in the main text. (I) Violin plots displaying the distribution of phosphopeptide abundance values following SPARK depletion. The distributions of candidate PKA C3 targets are shown in green. The distributions and p-values (KS test) were derived from the overlapping subset of phosphopeptides identified in each dataset. (J) Heat map of the abundance ratios of candidate PKA C3 targets following SPARK depletion. (K) Heat map of the abundance ratios of dense granule proteins following SPARK depletion, as discussed in the text.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 7D.

mNG, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig7-data1-v1.zip

-

Figure 7—source data 2

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 7D.

V5, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig7-data2-v1.zip

-

Figure 7—source data 3

This file contains source data that was used to generate the blot in Figure 7D.

ALD1, LICOR.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/93877/elife-93877-fig7-data3-v1.zip

SPARK down-regulation does not reduce PKA C3 protein levels

To determine whether SPARK activity affects PKA C3 abundance, as for PKA C1 and PKG, we tagged the endogenous PKA C3 C terminus with an mNG fluorophore in the SPARK-AID background. After 24 hr of IAA treatment, PKA C3 levels were unaltered or slightly elevated, as measured by immunoblot (Figure 7B–C). Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry measurements of mNG intensity after 0, 3, 8, and 24 hr of IAA treatment revealed a trend towards increasing PKA C3 abundance, although this difference was not significant (Figure 7D–F). Thus, unlike PKA C1, PKA C3 does not exhibit down-regulation following SPARK depletion. We considered the possibility that SPARK function could instead alter PKA C3 activity.

The PKA C3 phosphoproteome identifies candidates regulating the transition to the bradyzoite state

To pursue the functional consequences of PKA C3 inhibition, we performed a depletion phosphoproteomics time course experiment with the PKA C3-AID strain following 1, 3, 8, or 24 hr of IAA treatment (Supplementary file 3). PKA C3-dependent phosphopeptides were identified as for the SPARK depletion proteome (Figure 7G). The resulting proteome identified 4792 proteins and 12,721 phosphopeptides, of which 9576 were quantified with more than one PSM. PCA separated the 24 hr IAA samples from all others (Figure 7—figure supplement 1). Similar to the SPARK depletion proteome, several of the up-regulated proteins were reported to be transcriptional signatures of the bradyzoite stage, including BRP1, TGGT1_208740, two secreted cAMP-dependent protein kinases, and BFD2 (Figure 7—figure supplement 1).

To identify phosphopeptides most altered by IAA treatment, we summed and ranked phosphopeptides by log2-ratios of abundances in the PKA C3-AID strain relative to the untreated (0 hr) samples (Figure 7G). By this metric, 129 phosphopeptides (94 with >1 PSMs) and 49 phosphopeptides (31 with >1 PSMs) were down- or up-regulated by more than 3.5 in the modified Z-scores, respectively. Gaussian mixture-model algorithms heuristically clustered phosphopeptides identified by more than one PSM into three classes (Figure 7H). Cluster 1 contained 12 phosphopeptides that rapidly decreased within 1–3 hr of PKA C3 depletion and continued to decrease thereafter. This cluster includes CBP80, a DEP domain protein, TgZnT, TgApiAT3-1, AC13, and FtsH1 (Table 1).

Cluster 2 comprised 82 phosphopeptides that also decreased within 1–3 hr of IAA treatment, after which their abundances remained stable, overall decreasing to a lesser extent than cluster 1 (Figure 7H). Cluster 2 included genes putatively involved in gene regulation, including eIF4G1, NOC3p, a zinc finger protein, a DNA repair protein, SET1, and a nucleotidyltransferase (Table 1). Several phosphosites belonging to proteins involved in daughter cell biogenesis were also down-regulated, including AC13, IAP2, BCC8, and condensin 2. We also observed down-regulated phosphosites for transporters in this cluster—for example, TgApiAT2, ATP4, and a nucleoside transporter. The early events in bradyzoite differentiation have not been extensively characterized but involve translational regulation of BFD1 enhanced by a BFD1/BFD2 feed-forward loop (Licon et al., 2023; Waldman et al., 2020). Down-regulation of PKA C3 may enhance conditions that activate this loop, for example due to global down-regulation of cap-dependent translation (CBP80, eIF4G1) or alteration of the replicative cycle (Radke et al., 2003).

Cluster 2 also contains numerous proteins trafficking through secretory organelles, including the micronemes, rhoptries, and dense granules. Modified phosphosites belonging to micronemal proteins included CRMPb, TGGT1_221180, and TGGT1_304490 (Table 1). The rhoptry proteins ROP1, ROP13, ROP17, ROP40, and RON9 were also differentially regulated. Modified dense granule/parasitophorous vacuole proteins included GRA3, GRA4, GRA6, GRA7, GRA8, GRA31, GRA57, GRA62, GRA70, SFP1, and MAG1. Many of these proteins are lumenal within their respective organelles, and regulation by PKA C3 is therefore likely indirect. Nonetheless, each of the secretory organelles contain stage-specific subproteomes with implications for metabolism and protein complex assembly in bradyzoites (Sinai et al., 2020); the regulation observed here may reflect such early stages of proteomic remodeling.

The 31 phosphopeptides belonging to cluster 3 increased in abundance following PKA C3 depletion and therefore are likely indirect targets of the kinase. This cluster contained phosphoproteins involved in gene regulation (Table 1), such as AP2XII-9, an ISWI protein, CAF1, PLU-1, GCFC, and two zinc finger proteins: TGGT1_223880 and BFD2. We also identified several candidates involved in proteostasis, including HSP90, p23, CSN3, PSME4. Regulation of such proteins may be related to the transition to the bradyzoite state, albeit not as a direct consequence of PKA activity.

The protein phosphatase PP2A has recently been characterized as a regulator of bradyzoite differentiation (Wang et al., 2022). We therefore analyzed proteins that exhibited both PKA C3- and PP2A-dependent phosphoregulation. Several candidates in this category were identified as differentially important in interferon-stimulated cells, including TGGT1_209500, GRA57, and GRA70. Numerous phosphosites belonging to AC13 were differentially regulated in both phosphoproteomes. Some proteins involved in endo- and exocytosis also exhibited dynamic phosphoregulation, including CRMPb and Kelch13. PKA R S27 was up-regulated upon PKA C3 depletion and was also up-regulated in ∆pp2a mutants. Finally, nucleic-acid-binding proteins exhibited differential phosphoregulation, including BFD2, a KH protein, eIF4G2, and AP2XII-1. Given the stage conversion phenotypes of parasites lacking PKA C3 or PP2A, the phosphoregulation of overlapping targets may be functionally important in the context of bradyzoite differentiation.

The SPARK phosphoproteome shares signatures with the PKA C3–depletion phosphoproteome

We systematically compared the abundances of candidate PKA C3 targets (as defined above) to overlapping phosphosites in the SPARK phosphoproteome. Compared to the bulk phosphoproteome, the PKA C3–dependent phosphopeptides significantly decreased in abundance within three h of SPARK depletion (Figure 7I). Several of the phosphoproteins found to be altered by both PKA C3 and SPARK depletion belonged to proteins involved in gene regulation (Figure 7J and Table 1), including CBP80, eIF4G2, SET1, NOC3p, Spt5, a KH protein, a nucleotidyltransferase, and PRP4. Some of these proteins associate with large transcription factor assemblies, including the AP2IX4/MORC and GCN5b complexes. Transporters also overlapped between the two phosphoproteomes, including ZnT, TgApiAT2, and TgApiAT3-1. Several phosphosites belonging to apical cap proteins were also shared between the phosphoproteomes, including numerous AC13 phosphopeptides.

The SPARK and PKA C3 phosphoproteomes notably diverged with regards to regulation of dense granule proteins, which was observed as a subpopulation of PKA C3–dependent phosphopeptides that increased in abundance upon SPARK depletion (Figure 7I and K). This effect was specific to the indicated phosphopeptides, as corresponding protein levels of the dense granule proteins were not changed (Supplementary file 4). The differentially regulated dense granule proteins include many of those belonging to cluster 2 of the PKA C3 depletion proteome (Figure 7H and K). The phosphoproteome of SPARK shares signatures of reduced PKA C3 activity; however, due to concomitant down-regulation of other AGC kinases, the phosphoproteomes of SPARK and PKA C3 depletion diverge in ways that remain to be explored.

Discussion