We have previously described two sets of results from a peer-review trial in which 313 authors opted in to a process that gave them greater control over the decision to publish. If the editors agreed to review the work in depth, eLife was then committed to publishing the work, unless the authors decided to withdraw the paper. Early in the trial, we reported on the encouragement rate and the time to first decision (see ‘First results from a trial at eLife’). Then, we shared results from the peer-review process itself for 70 trial papers that had been peer reviewed in depth and 162 papers that went through the regular review process during the same period of time (see ‘Further results from a trial at eLife’). Of the papers reviewed in depth in the regular process, 94 were invited for revisions, 66 were rejected after review, one was accepted outright, and one was withdrawn. Using a cut-off point of one year since closing for submissions (August 8, 2019), we now present the final outcomes covering resubmission and acceptance. In the trial process, 65 papers have been accepted, two were withdrawn by the authors, and three remain pending (at the cut-off point). The papers in the trial have been published as Research Communications. Out of 94 revised submissions in the regular process, 91 have been accepted and three ended up being rejected after revisions.

Acceptance rates

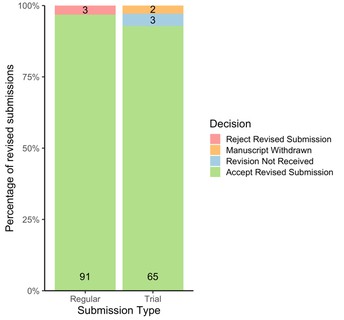

Figure 1. Decisions after resubmission in the regular and trial processes. Black numbers in bars show the number of submissions.

Figure 1 shows decision outcomes for revised submissions. In the regular process, 97% of revised submissions went on to be accepted.

In the trial process, one manuscript was withdrawn after the peer-review process, and one was withdrawn after the final rating was decided. Whereas all papers in the regular process had reached a final decision at the cut-off point, there were three trial papers where a final decision was pending (“Revision Not Received”).

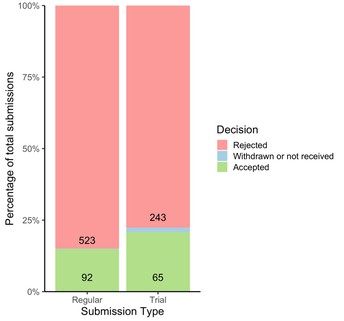

Figure 2 shows the overall acceptance rates, with 14.9% of papers in the regular process accepted, compared with 20.8% in the trial process. This means that despite a higher proportion of papers being rejected before peer review in the trial (see ‘First results from a trial at eLife’), a greater percentage end up being published overall.

Figure 2. Final decision outcomes in the regular and trial processes. Black numbers indicate the number of submissions. One submission in the regular process was withdrawn, with five cases in the trial process withdrawn or pending. One submission in the regular process was accepted outright after review, without asking for revisions.

Editorial ratings

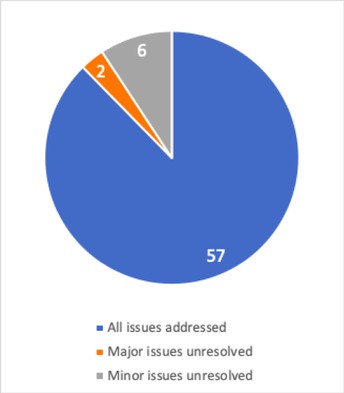

Papers in the trial process received an editorial rating from the Reviewing Editor. Three ratings were available: i) all the issues raised in the review process have been addressed in the revised version; ii) minor issues raised in the review process remain unresolved; iii) major issues raised in the review process remain unresolved. Figure 3 shows that 88% of trial submissions (57/65) were considered to have addressed all the issues raised during the review process, with minor issues unresolved in 9% of cases (n=6) and major issues unresolved in 3% (n=2).

Figure 3. Editorial ratings for accepted trial submissions.

Time to acceptance

Figure 4 shows the time to acceptance for submissions going through one, two and three rounds of revision. For the majority of papers, accepted after one round of revision, the median time to acceptance in the regular process was 129 days, shorter than the trial process at 157 days.

It is important to note the differences in the process here: in the regular process, reviewers are asked to consider whether the work they are requesting can be completed within two months, whereas reviewers in the trial process are asked to comment on the strengths and weaknesses of the study, and the authors then decide what revisions to undertake without a suggested time frame for resubmission.

Figure 4. Days from submission to acceptance, broken down by the number of rounds of revision. Black numbers depict the number of submissions. One paper, which was accepted without requesting revisions in the regular process, is not shown.

When accounting for all rounds of revision, Table 1 shows that the median time to acceptance was 138 days in the regular process overall and 175 days in the trial process. Longer revision times in the trial process account for much of this difference, although in previous blogposts we observed slightly longer initial decision times and slightly longer review times for papers in the trial process.

| Submission type | Median | Q1 | Q3 | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | 138 | 113 | 168 | 55 |

| Trial | 175 | 129 | 230 | 101 |

Table 1. Overall days from submission to acceptance.

Gender and career stage

In earlier blogposts we considered decision outcomes by both the gender and career stage of the last author. In ‘First results from a trial at eLife’, we reported that the encourage rate (proportion of submissions sent for in-depth review) was similar for male and female last authors (22.6% and 22.1% respectively), but that there was a slightly bigger difference for regular submissions (with 31% of submissions with male last authors encouraged for review compared with 28.8% of submissions with a female last author). In Figure 5, we show the overall acceptance rates for male and female last authors. In the trial process, again there is very little difference in the acceptance rates for male and female last authors (21% and 20.6% respectively). In the regular process, we see a slightly higher acceptance rate of 16.8% for female last authors (n=24) compared with 14.9% for male last authors (n=67), although the small sample size means that this should be treated with caution.

Figure 5. Final decision outcomes by gender of the last author. Black numbers in bars indicate the number of submissions for each decision, submission type and gender combination. One trial submission with a female last author remains pending at the time of publication; for male last authors, one submission was withdrawn in the regular process, while two were withdrawn and two remain pending in the trial process.

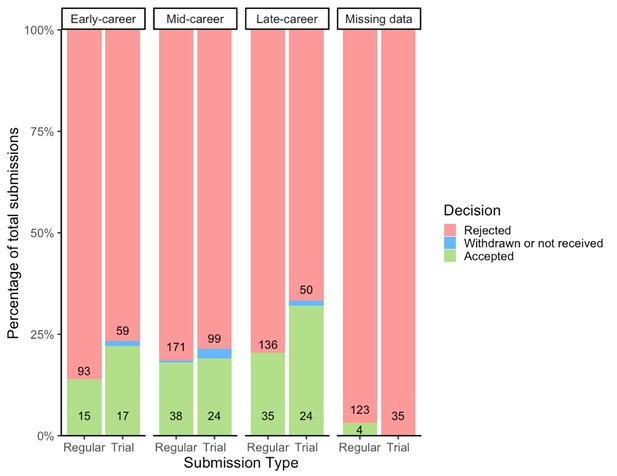

Figure 6 shows the final decision outcomes by career stage of the last author. In ‘First results from a trial at eLife’, we reported that papers were less likely to be encouraged for in-depth review in the trial process compared with the regular process. This was particularly true for early- and mid-career last authors, where the difference in encouragement rate was -7.1% for early-career last authors and -14.9% for mid-career last authors. By the end of the trial process, we ended up with an acceptance rate of 22% for early-career researchers (compared with 14% in the regular process), 19% for mid-career researchers (compared with 18% in the regular process), and 32% for late-career last authors (compared with 20.5% in the regular process). For reasons we do not fully understand, late-career authors have better acceptance rates than authors from the other career stages, and this difference is more pronounced for papers in the trial process.

Figure 6. Final decision outcomes by career stage of the last author. Numbers in bars indicate the number of submissions for each decision, career stage and submission type. As before, for the purposes of this trial, an early-career submission is one where the last author had been independent for five years or less, a mid-career submission is one where the last author had been independent for six–15 years, and a late-career submission is where the last author had been independent for more than 15 years. In the regular process, one paper was withdrawn (mid-career last author). In the trial process, three manuscripts are pending at the time of publication (one early-career, one mid-career and one late-career last author) and two manuscripts were withdrawn (both from mid-career last authors).

Summary

There are still three papers in the trial that have not reached a final decision. Nevertheless, we have already gained valuable insights into eLife’s regular and trial peer-review processes, based on the 665 regular submissions and 313 papers in the trial process. The trial process appears to have taken longer at each stage, although that is to some extent to be expected as it was unfamiliar to editors and reviewers. The trial process ended up with a moderately higher acceptance rate (20.8% compared with 14.9% in the regular process). We have also seen that earlier-career labs tended to have lower acceptance rates in both processes. Since the last blogpost in July, we have started to collect information about the career stage of the last author during submission so that we can see if this remains true with a larger dataset.

One of the initial concerns about the trial process was the additional pressure on the initial decision to reject or review a paper in depth, given that the paper would then be published subject to the approval of the authors. At the end of the trial process, we have seen the full range of possible outcomes once the decision to publish has passed to the authors: a small number of authors withdrew after the first or second round of review, but the vast majority decided to proceed with publication, including some where the editors determined that major issues remained unresolved.

By removing the decision to reject after review in the trial process, and by publishing the peer reviews, author responses and editorial ratings, we have begun to show how the peer-review process does not need to end with a binary outcome of acceptance or rejection, and we have started to expose some of its nuances more effectively. We therefore plan to build upon what we have learned with upcoming initiatives to show how the results of the review process can be published in an informative way. eLife’s editorial leadership will shortly share their views on the lessons learned from the trial and the next steps that we will take.

#

We welcome comments/questions from researchers as well as other journals. Please annotate publicly on the article or contact us at hello [at] elifesciences [dot] org.

For the latest in published research sign up for our weekly email alerts. You can also follow @eLife on Twitter.