Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorFelix CampeloUniversitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

- Senior EditorFelix CampeloUniversitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

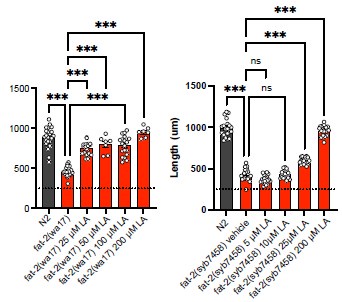

This study addresses the roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal physiology and membrane function. A C. elegans strain carrying the fat-2(wa17) mutation possess a very limited ability to synthesize PUFAs and there is no dietary input because the E. coli diet consumed by lab grown C. elegans does not contain any PUFAs. The fat-2 mutant strain was characterized to confirm that the worms grow slowly, have rigid membranes, and have a constitutive mitochondrial stress response. The authors showed that chemical treatments or mutations known to increase membrane fluidity did not rescue growth defects. A thorough genetic screen was performed to identify genetic changes to compensate for the lack of PUFAs. The newly isolated suppressor mutations that compensated for FAT-2 growth defects included intergenic suppressors in the fat-2 gene, as well as constitutive mutations in the hypoxia sensing pathway components EGL-9 and HIF-1, and loss of function mutations in ftn-2, a gene encoding the iron storage protein ferritin. Taken together, these mutations lead to the model that increased intracellular iron, an essential cofactor for fatty acid desaturases, allows the minimally functional FAT-2(wa17) enzyme to be more active, resulting in increased desaturation and increased PUFA synthesis.

Strengths:

(1) This study provides new information further characterizing fat-2 mutants. The authors measured increased rigidity of membranes compared to wild type worms, however this rigidity is not able to be rescued with other fluidity treatments such as detergent or mutants. Rescue was only achieved with polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation.

(2) A very thorough genetic suppressor screen was performed. In addition to some internal fat-2 compensatory mutations, the only changes in pathways identified that are capable of compensating for deficient PUFA synthesis was the hypoxia pathway and the iron storage protein ferritin. Suppressor mutations included an egl-9 mutation that constitutively activates HIF-1, and Gain of function mutations in hif-1 that are dominant. This increased activity of HIF conferred by specific egl-9 and hif-1 mutations lead to decreased expression of ftn-2. Indeed, loss of ftn-2 leads to higher intracellular iron. The increased iron apparently makes the FAT-2 fatty acid desaturase enzyme more active, allowing for the production of more PUFAs.

(3) The mutations isolated in the suppressor screen show that the only mutations able to compensate for lack of PUFAs were ones that increased PUFA synthesis by the defective FAT-2 desaturase, thus demonstrating the essential need for PUFAs that cannot be overcome by changes in other pathways. This is a very novel study, taking advantage of genetic analysis of C. elegans, and it confirms the observations in humans that certain essential PUFAs are required for growth and development.

(4) Overall, the paper is well written, and the experiments were carried out carefully and thoroughly. The conclusions are well supported by the results.

Weaknesses:

Overall, there are not many weaknesses. The main one I noticed is that the lipidomic analysis shown in Figs 3C, 7C, S1 and S3. Whie these data are an essential part of the analysis and provide strong evidence for the conclusions of the study, it is unfortunate that the methods used did not enable the distinction between two 18:1 isomers. These two isomers of 18:1 are important in C. elegans biology, because one is a substrate for FAT-2 (18:1n-9, oleic acid) and the other is not (18:1n-7, cis vaccenic acid). Although rarer in mammals, cis-vaccenic acid is the most abundant fatty acid in C. elegans and is likely the most important structural MUFA. The measurement of these two isomers is not essential for the conclusions of the study, but the manuscript should include a comment about the abundance of oleic vs vaccenic acid in C. elegans (authors can find this information, even in the fat-2 mutant, in other publications of C. elegans fatty acid composition). Otherwise, readers who are not familiar with C. elegans might assume the 18:1 that is reported is likely to be mainly oleic acid, as is common in mammals.

Other suggestions to authors to improve the paper:

(1) The title could be less specific; it might be confusing to readers to include the allele name in the title.

(2) There are two errors in the pathway depicted in Figure 1A. The16:0-16:1 desaturation can be performed by FAT-5, FAT-6, and FAT-7. The 18:0-18:1 desaturation can only be performed by FAT-6 and FAT-7

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors use a genetic screen in C. elegans to investigate the physiological roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). They screen for mutations that rescue fat-2 mutants, which have strong reductions in PUFAs. As a result, either mutations in fat-2 itself, or mutations in genes involved in the HIF-1 pathway, were found to rescue fat-2 mutants. Mutants in the HIF-1 pathway rescue fat-2 mutants by boosting its catalytic activity (via upregulated Fe2+). Thus, the authors show that in the context of fat-2 mutation, the sole genetic means to rescue PUFA insufficiency is to restore PUFA levels.

Strengths:

As C. elegans can produce PUFAs de novo as essential lipids, the genetic model is well suited to study the fundamental roles of PUFAs. The genetic screen finds mutations in convergent pathways, suggesting that it has reached near-saturation. The authors extensively validate the results of the screening and provide sufficient mechanistic insights to show how PUFA levels are restored in HIF-1 pathway mutants. As many of the mutations found to rescue fat-2 mutants are of gain-of-function, it is unlikely that similar discoveries could have been made with other approaches like genome-wide CRISPR screenings, making the current study distinctive. Consequently, the study provides important messages. First, it shows that PUFAs are essential for life. The inability to genetically rescue PUFA deficiency, except for mutations that restore PUFA levels, suggests that they have pleiotropic essential functions. In addition, the results suggest that the most essential functions of PUFAs are not in fluidity regulation, which is consistent with recent reviews proposing that the importance of unsaturation goes beyond fluidity (doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2023.08.004 and doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a041409). Thus, the study provides fundamental insights about how membrane lipid composition can be linked to biological functions.

Weaknesses:

The authors did a lot of efforts to answer the questions that arose through peer review, and now all the claims seem to be supported by experimental data. Thus, I do not see obvious weaknesses. Of course, it remains still unclear what PUFAs do beyond fluidity regulation, but this is something that cannot be answered from a single study. I just have one final proposition to make.

I still do not agree with the answer to my previous comment 6 regarding Figure S2E. The authors claim that hif-1(et69) suppresses fat-2(wa17) in a ftn-2 null background (in Figure S2 legend for example). To claim so, they would need to compare the triple mutant with fat-2(wa17);ftn-2(ok404) and show some rescue. However, we see in Figure 5H that ftn-2(ok404) alone rescues fat-2(wa17). Thus, by comparing both figures, I see no additional effect of hif-1(et69) in an ftn-2(ok404) background. I actually think that this makes more sense, since the authors claim that hif-1(et69) is a gain-of-function mutation that acts through suppression of ftn-2 expression. Thus, I would expect that without ftn-2 from the beginning, hif-1(et69) does not have an additional effect, and this seems to be what we see from the data. Thus, I would suggest that the authors reformulate their claims regarding the effect of hif-1(et69) in the ftn-2(ok404) background, which seems to be absent (consistently with what one would expect).