Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorRoshan CoolsDonders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- Senior EditorJonathan RoiserUniversity College London, London, United Kingdom

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

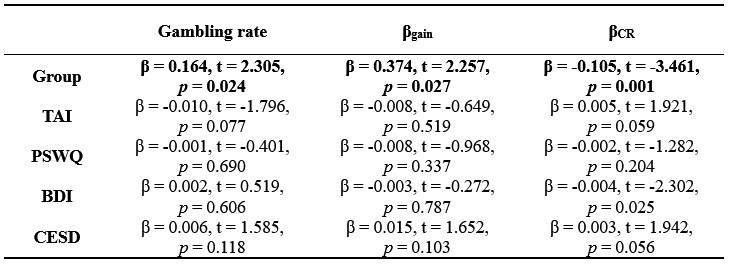

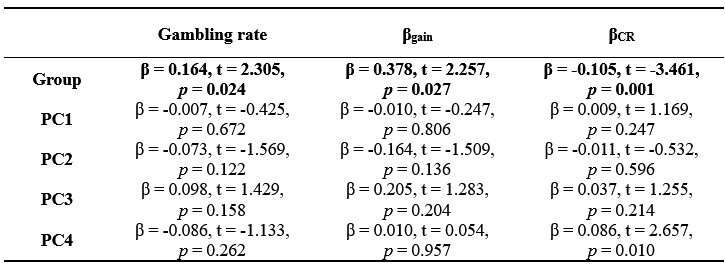

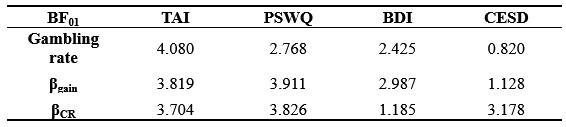

The authors use a gambling task with momentary mood ratings from Rutledge et al. and compare computational models of choice and mood to identify markers of decisional and affective impairments underlying risk-prone behavior in adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STB). The results show that adolescents with STB show enhanced gambling behavior (choosing the gamble rather than the sure amount), and this is driven by a bias towards the largest possible win rather than insensitivity to possible losses. Moreover, this group shows a diminished effect of receiving a certain reward (in the non-gambling trials) on mood. The results were replicated in an undifferentiated online sample where participants were divided into groups with or without STB based on their self-report of suicidal ideation on one question in the Beck Depression Inventory self-report instrument. The authors suggest, therefore, that adolescents with decreased sensitivity to certain rewards may need to be monitored more closely for STB due to their increased propensity to take risky decisions aimed at (expected) gains (such as relief from an unbearable situation through suicide), regardless of the potential losses.

Strengths:

(1) The study uses a previously validated task design and replicates previously found results through well-explained model-free and model-based analyses.

(2) Sampling choice is optimal, with adolescents at high risk; an ideal cohort to target early preventative diagnoses and treatments for suicide.

(3) Replication of the results in an online cohort increases confidence in the findings.

(4) The models considered for comparison are thorough and well-motivated. The chosen models allow for teasing apart which decision and mood sensitivity parameters relate to risky decision-making across groups based on their hypotheses.

(5) Novel finding of mood (in)sensitivity to non-risky rewards and its relationship with risk behavior in STB.

Weaknesses:

(1) The sample size of 25 for the S- group was justified based on previous studies (lines 181-183); however, all three papers cited mention that their sample was low powered as a study limitation.

(2) Modeling in the mediation analysis focused on predicting risk behavior in this task from the model-derived bias for gains and suicidal symptom scores. However, the prediction of clinical interest is of suicidal behaviors from task parameters/behavior - as a psychiatrist or psychologist, I would want to use this task to potentially determine who is at higher risk of attempting suicide and therefore needs to be more closely watched rather than the other way around (predicting behavior in the task from their symptom profile). Unfortunately, the analyses presented do not show that this prediction can be made using the current task. I was left wondering: is there a correlation between beta_gain and STB? It is also important to test for the same relationships between task parameters and behavior in the healthy control group, or to clarify that the recommendations for potential clinical relevance of these findings apply exclusively to people with a diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorder. Indeed, in line 672, the authors claim their results provide "computational markers for general suicidal tendency among adolescents", but this was not shown here, as there were no models predicting STB within patient groups or across patients and healthy controls.

(3) The FDR correction for multiple comparisons mentioned briefly in lines 536-538 was not clear. Which analyses were included in the FDR correction? In particular, did the correlations between gambling rate and BSI-C/BSI-W survive such correction? Were there other correlations tested here (e.g., with the TAI score or ERQ-R and ERQ-S) that should be corrected for? Did the mediation model survive FDR correction? Was there a correction for other mediation models (e.g., with BSI-W as a predictor), or was this specific model hypothesized and pre-registered, and therefore no other models were considered? Did the differences in beta_gain across groups survive FDR when including comparisons of all other parameters across groups? Because the results were replicated in the online dataset, it is ok if they did not survive FDR in the patient dataset, but it is important to be clear about this in presenting the findings in the patient dataset.

(4) There is a lack of explicit mention when replication analyses differ from the analyses in the patient sample. For instance, the mediation model is different in the two samples: in the patient sample, it is only tested in S+ and S- groups, but not in healthy controls, and the model relates a dimensional measure of suicidal symptoms to gambling in the task, whereas in the online sample, the model includes all participants (including those who are presumably equivalent to healthy controls) and the predictor is a binary measure of S+ versus S- rather than the response to item 9 in the BDI. Indeed, some results did not replicate at all and this needs to be emphasized more as the lack of replication can be interpreted not only as "the link between mood sensitivity to CR and gambling behavior may be specifically observable in suicidal patients" (lines 582-585) - it may also be that this link is not truly there, and without a replication it needs to be interpreted with caution.

(5) In interpreting their results, the authors use terms such as "motivation" (line 594) or "risk attitude" (line 606) that are not clear. In particular, how was risk attitude operationalized in this task? Is a bias for risky rewards not indicative of risk attitude? I ask because the claim is that "we did not observe a difference in risk attitude per se between STB and controls". However, it seems that participants with STB chose the risky option more often, so why is there no difference in risk attitude between the groups?

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This article addresses a very pertinent question: what are the computational mechanisms underlying risky behaviour in patients who have attempted suicide? In particular, it is impressive how the authors find a broad behavioural effect whose mechanisms they can then explain and refine through computational modeling. This work is important because, currently, beyond previous suicide attempts, there has been a lack of predictive measures. This study is the first step towards that: understanding the cognition on a group level. This is before being able to include it in future predictive studies (based on the cross-sectional data, this study by itself cannot assess the predictive validity of the measure).

Strengths:

(1) Large sample size.

(2) Replication of their own findings.

(3) Well-controlled task with measures of behaviour and mood + precise and well-validated computational modeling.

Weaknesses:

I can't really see any major weakness, but I have a few questions:

(1) I can see from the parameter recovery that the parameters are very well identified. Is it surprising that this is the case, given how many parameters there are for 90 trials? Could the authors show cross-correlations? I.e., make a correlation matrix with all real parameters and all fitted parameters to show that not only the diagonal (i.e., same data is the scatter plots in S3) are high, but that the off-diagonals are low.

(2) Could the authors clarify the result in Figure 2B of a correlation between gambling rate and suicidal ideation score, is that a different result than they had before with the group main effect? I.e., is your analysis like this: gambling rate ~ suicide ideation + group assignment? (or a partial correlation)? I'm asking because BSI-C is also different between the groups. [same comment for later analyses, e.g. on approach parameter].

(3) The authors correlate the impact of certain rewards on mood with the % gambling variable. Could there not be a more direct analysis by including mood directly in the choice model?

(4) In the large online sample, you split all participants into S+ and S-. I would have imagined that instead, you would do analyses that control for other clinical traits. Or, for example, you have in the S- group only participants who also have high depression scores, but low suicide items.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This manuscript investigates computational mechanisms underlying increased risk-taking behavior in adolescent patients with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Using a well-established gambling task that incorporates momentary mood ratings and previously established computational modeling approaches, the authors identify particular aspects of choice behavior (which they term approach bias) and mood responsivity (to certain rewards) that differ as a function of suicidality. The authors replicate their findings on both clinical and large-scale non-clinical samples.

The main problem, however, is that the results do not seem to support a specific conclusion with regard to suicidality. The S+ and S- groups differ substantially in the severity of symptoms, as can be seen by all symptom questionnaires and the baseline and mean mood, where S- is closer to HC than it is to S+. The main analyses control for illness duration and medication but not for symptom severity. The supplementary analysis in Figure S11 is insufficient as it mistakes the absence of evidence (i.e., p > 0.05) for evidence of absence. Therefore, the results do not adequately deconfound suicidality from general symptom severity.

The second main issue is that the relationship between an increased approach bias and decreased mood response to CR is conceptually unclear. In this respect, it would be natural to test whether mood responses influence subsequent gambling choices. This could be done either within the model by having mood moderate the approach bias or outside the model using model-agnostic analyses.

Additionally, there is a conceptual inconsistency between the choice and mood findings that partly results from the analytic strategy. The approach bias is implemented in choice as a categorical value-independent effect, whereas the mood responses always scale linearly with the magnitude of outcomes. One way to make the models more conceptually related would be to include a categorical value-independent mood response to choosing to gamble/not to gamble.

The manuscript requires editing to improve clarity and precision. The use of terms such as "mood" and "approach motivation" is often inaccurate or not sufficiently specific. There are also many grammatical errors throughout the text.

Claims of clinical relevance should be toned down, given that the findings are based on noisy parameter estimates whose clinical utility for the treatment of an individual patient is doubtful at best.