Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorC Brandon OgbunugaforYale University, New Haven, United States of America

- Senior EditorDetlef WeigelMax Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Assessment

This study develops a potentially useful metric for quantifying codon usage adaptation – the Codon Adaptation Index of Species (CAIS) – that is intended to allow for more direct comparisons of the strength of selection at the molecular level across species by controlling for interspecies variation in amino acid usage and GC content. As evidence to support there claim CAIS better controls for GC content and amino acid usage across species, they note that CAIS has only a weak positive correlation with GC% (that does not stand up to multiple hypothesis testing correction) while CAI has a clear negative correlation with GC%. Using CAIS, they find better adapted species have more disordered protein domains; however, excitement about these findings is dampened due to (1) this result is also observed using the effective number of codons (ENC) and

(2) concerns over the interpretation of CAIS as a proxy for the effectiveness of selection.

Public Review

Summary

The goal of the authors in this study is to develop a more reliable approach for quantifying codon usage such that it is more comparable across species. Specifically, the authors wish to estimate the degree of adaptive codon usage, which is potentially a general proxy for the strength of selection at the molecular level. To this end, the authors created the Codon Adaptation Index for Species (CAIS) that attempts to control for differences in amino acid usage and GC% across species. Using their new metric, the authors observe a positive relationship between CAIS and the overall “disorderedness” of a species protein domains. I think CAIS has the potential to be a valuable tool for those interested in comparing codon adaptation across species in certain situations. However, I have certain theoretical concerns about CAIS as a direct proxy for the efficiency of selection sNe when mutation bias changes across species.

Strengths

(1) I appreciate that the authors recognize the potential issues of comparing CAI when amino acid usage varies and correct for this in CAIS. I think this is sometimes an under-appreciated point in the codon usage literature, as CAI is a relative measure of codon usage bias (i.e. only considers synonyms). However, the strength of natural selection on codon usage can potentially vary across amino acids, such that comparing mean CAI between protein regions with different amino acid biases may result in spurious signals of statistical significance.

(2) The CAIS metric presented here is generally applicable to any species that has an annotated genome with protein-coding sequences. A significant improvement over the previous version is the implementation of software tool for applying this method.

(3) The authors do a better job of putting their results in the context of the underlying theory of CAIS compared to the previous version.

(4) The paper is generally well-written.

Weaknesses

(1) The previously observed correlation between CAIS and body size was due to a bug when calculating phylogenetic independent contrasts. I commend the authors for acknowledging this mistake and updating the manuscript accordingly. I feel that the unobserved correlation between CAIS and body size should remain in the final version of the manuscript. Although it is disappointing that it is not statistically significant, the corrected results are consistent with previous findings (Kessler and Dean 2014).

(2) I appreciate the authors for providing a more detailed explanation of the theoretical basis model. However, I remain skeptical that shifts in CAIS across species indicates shifts in the strength of selection. I am leaving the math from my previous review here for completeness.

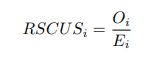

As in my previous review, let’s take a closer look at the ratio of observed codon frequencies vs. expected codon frequencies under mutation alone, which was previously notated as RSCUS in the original formulation. In this review, I will keep using the RSCUS notation, even though it has been dropped from the updated version. The key point is this is the ratio of observed and expected codon frequencies. If this ratio is 1 for all codons, then CAIS would be 0 based on equation 7 in the manuscript – consistent with the complete absence of selection on codon usage. From here on out, subscripts will only be used to denote the codon and it will be assumed that we are only considering the case of r = genome for some species s.

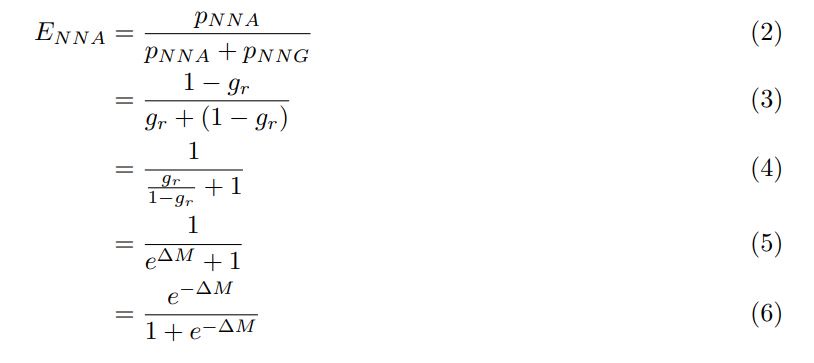

I think what the authors are attempting to do is “divide out” the effects of mutation bias (as given by Ei), such that only the effects of natural selection remain, i.e. deviations from the expected frequency based on mutation bias alone represents adaptive codon usage. Consider Gilchrist et al. GBE 2015, which says that the expected frequency of codon i at selection-mutation-drift equilibrium in gene g for an amino acid with Na synonymous codons is

where ∆M is the mutation bias, ∆η is the strength of selection scaled by the strength of drift, and φg is the gene expression level of gene g. In this case, ∆M and ∆η reflect the strength and direction of mutation bias and natural selection relative to a reference codon, for which ∆M,∆η = 0. Assuming the selection-mutation-drift equilibrium model is generally adequate to model of the true codon usage patterns in a genome (as I do and I think the authors do, too), the Ei,g could be considered the expected observed frequency codon i in gene g

E[Oi,g].

Let’s re-write the  in the form of Gilchrist et al., such that it is a function of mutation bias ∆M. For simplicity we will consider just the two codon case and assume the amino acid sequence is fixed. Assuming GC% is at equilibrium, the term gr and 1 − gr can be written as

in the form of Gilchrist et al., such that it is a function of mutation bias ∆M. For simplicity we will consider just the two codon case and assume the amino acid sequence is fixed. Assuming GC% is at equilibrium, the term gr and 1 − gr can be written as

where µx→y is the mutation rate from nucleotides x to y. As described in Gilchrist et al. MBE 2015 and Shah and Gilchrist PNAS 2011, the mutation bias  . This can be expressed in terms of the equilibrium GC content by recognizing that

. This can be expressed in terms of the equilibrium GC content by recognizing that

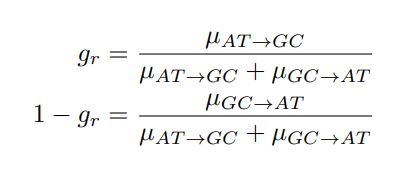

As we are assuming the amino acid sequence is fixed, the probability of observing a synonymous codon i at an amino acid becomes just a Bernoulli process.

If we do this, then

Recall that in the Gilchrist et al. framework, the reference codon has ∆MNNG,NNG = 0 =⇒ e−∆MNNG,NNG =

(1) Thus, we have recovered the Gilchrist et al. model from the formulation of Ei under the assumption that natural selection has no impact on codon usage and codon NNG is the pre-defined reference codon. To see this, plug in 0 for ∆η in equation (1).

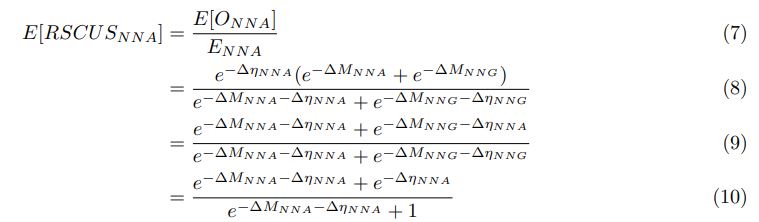

We can then calculate the expected RSCUS using equation (1) (using notation E[Oi]) and equation (6) for the two codon case. For simplicity assume, we are only considering a gene of average expression (defined as  ). Assume in this case that NNG is the reference codon (∆MNNG,∆ηNNG = 0).

). Assume in this case that NNG is the reference codon (∆MNNG,∆ηNNG = 0).

This shows that the expected value of RSCUS for a two codon amino acid is expected to increase as the strength of selection ∆η increases, which is desired. Note that ∆η in Gilchrist et al. is formulated in terms of selection against a codon relative to the reference, such that a negative value represents that a codon is favored relative to the reference. If ∆η = 0 (i.e. selection does not favor either codon), then E[RSCUS] = 1. Also note that the expected RSCUS does not remain independent of the mutation bias. This means that even if sNe (i.e. the strength of natural selection) does not change between species, changes to the strength and direction of mutation bias across species could impact RSCUS. Assuming my math is right, I think one needs to be cautious when interpreting CAIS as representative of the differences in the efficiency of selection across species except under very particular circumstances.

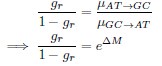

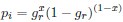

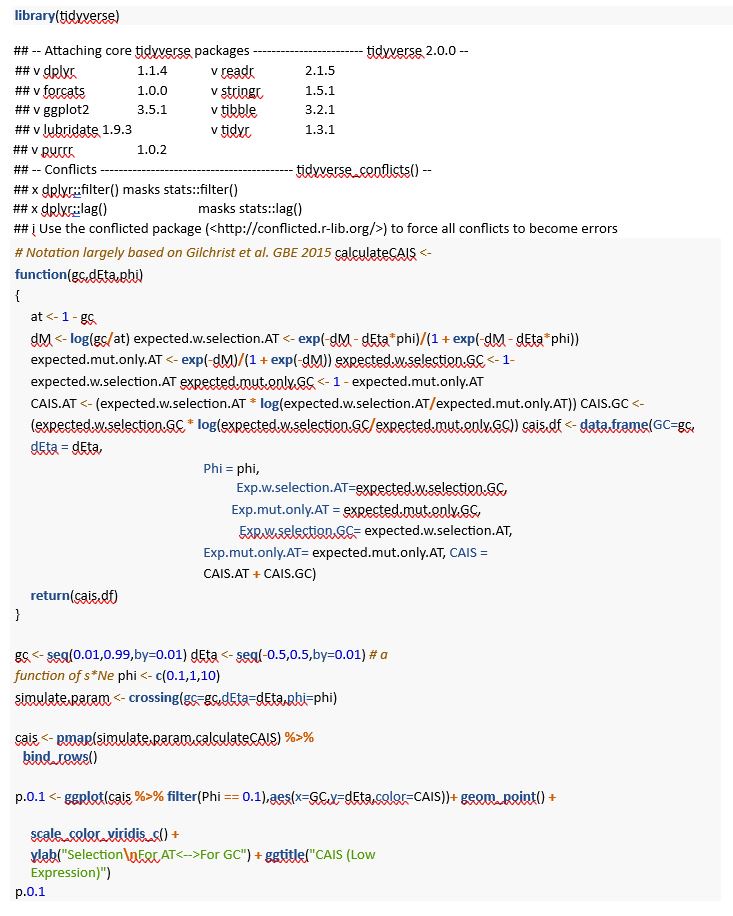

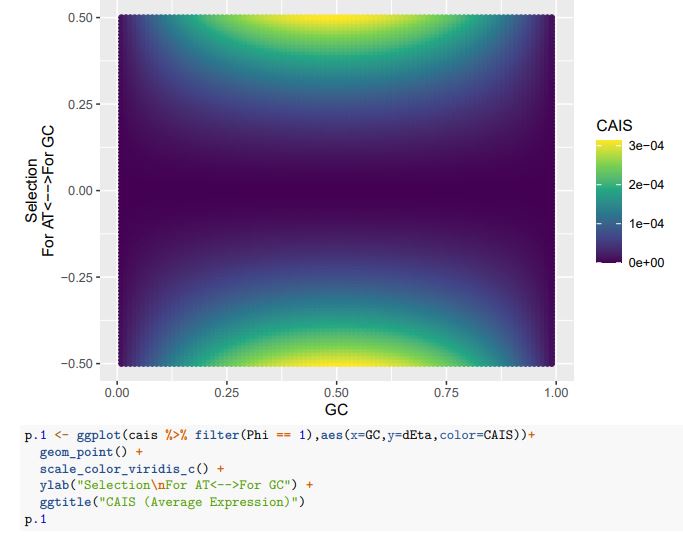

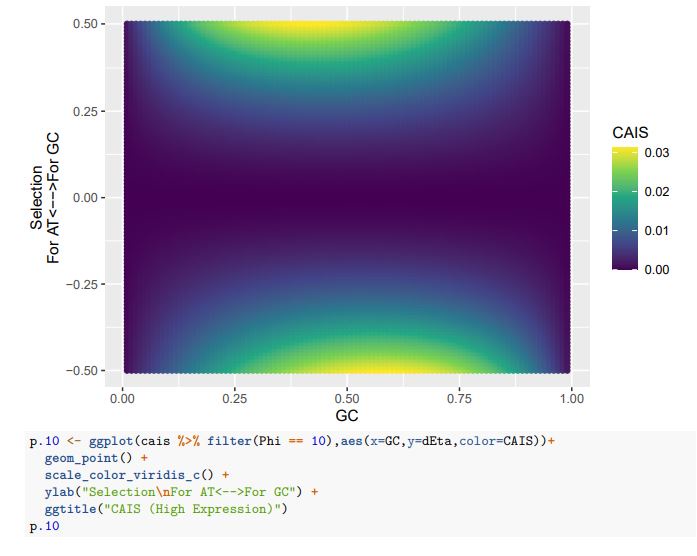

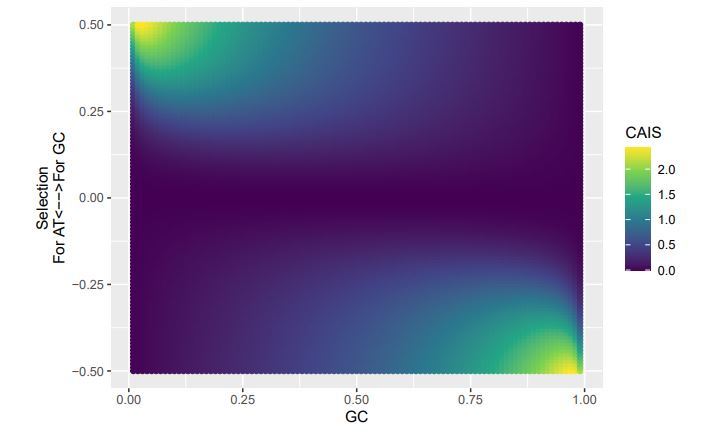

Consider our 2-codon amino acid scenario. You can see how changing GC content without changing selection can alter the CAIS values calculated from these two codons. Particularly problematic appears to be cases of extreme mutation biases, where CAIS tends toward 0 even for higher absolute values of the selection parameter. Codon usage for the majority of the genome will be primarily determined by mutation biases,

with selection being generally strongest in a relatively few highly-expressed genes. Strong enough mutation biases ultimately can overwhelm selection, even in highly-expressed genes, reducing the fraction of sites subject to codon adaptation.

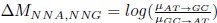

Peer review image 1.

Peer review image 2.

CAIS (Low Expression)

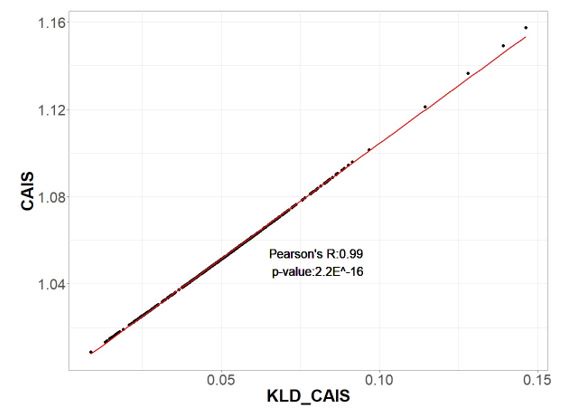

Peer review image 3.

CAIS (Average Expression)

Peer review image 4.

CAIS (High Expression)

If we treat the expected codon frequencies as genome-wide frequencies, then we are basically assuming this genome made up entirely of a single 2-codon amino acid with selection on codon usage being uniform across all genes. This is obviously not true, but I think it shows some of the potential limitations of the CAIS approach. Based on these simulations, CAIS seems best employed under specific scenarios. One such case could be when it is known that mutation bias varies little across the species of interest. Looking at the species used in this manuscript, most of them have a GC content around 0.41, so I suspect their results are okay (assuming things like GC-biased gene conversion are not an issue). Outliers in GC content probably are best excluded from the analysis.

Although I have not done so, I am sure this could be extended to the 4 and 6 codon amino acids. One potential challenge to CAIS is the non-monotonic changes in codon frequencies observed in some species (again, see Shah and Gilchrist 2011 and Gilchrist et al. 2015).