Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife assessment

This study has uncovered some important initial findings about how certain extracellular vehicles (EVs) from the mother might impact the energy usage of an embryo. While the study's findings are in general solid, some experiments lack statistical power due to small sample sizes. The study's title might be a bit too assertive as the evidence linking maternal mtDNA transmission to changes in embryo energy use is still correlative.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the editors and reviewers for their invaluable comments on this work. Their feedback has been instrumental in enhancing the quality of our manuscript; we have incorporated their suggestions to the best of our abilities.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Q1. Bolumar et al. isolated and characterized EV subpopulations, apoptotic bodies (AB), Microvesicles (MV), and Exosomes (EXO), from endometrial fluid through the female menstrual cycle. By performing DNA sequencing, they found the MVs contain more specific DNA sequences than other EVs, and specifically, more mtDNA were encapsulated in MVs. They also found a reduction of mtDNA content in the human endometrium at the receptive and post-receptive period that is associated with an increase in mitophagy activity in the cells, and a higher mtDNA content in the secreted MVs was found at the same time. Last, they demonstrated that the endometrial Ishikawa cell-derived EVs could be taken by the mouse embryos and resulted in altered embryo metabolism.

This is a very interesting study and is the first one demonstrating the direct transmission of maternal mtDNA to embryos through EVs.

A1. Thank you for your kind comments.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Q2. In Bolumar, Moncayo-Arlandi et al. the authors explore whether endometrium-derived extracellular vesicles contribute mtDNA to embryos and therefore influence embryo metabolism and respiration. The manuscript combines techniques for isolating different populations of extracellular vesicles, DNA sequencing, embryo culture, and respiration assays performed on human endometrial samples and mouse embryos.

Vesicle isolation is technically difficult and therefore collection from human samples is commendable. Also, the influence of maternally derived mtDNA on the bioenergetics of embryos is unknown and therefore novel. However, several experiments presented in the manuscript fail to reach statistical significance, likely due to the small sample sizes. Additionally, the experiments do not demonstrate a direct effect of mtDNA transfer on embryo bioenergetics. This has the unfortunate consequence of making several of the authors' conclusions speculative.

In my opinion the manuscript supports the following of the authors' claims:

- Different amounts of mtDNA are shed in human endometrial extracellular vesicles during different phases of the menstrual cycle

- Endometrial microvesicles are more enriched for mitochondrial DNA sequences compared to other types of microvesicles present in the human samples

- Fluorescently labelled DNA from extracellular vesicles derived from an endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line can be incorporated into hatched mouse embryos.

- Culture of mouse embryos with endometrial extracellular vesicles can influence embryo respiration and the effect is greater when cultured with isolated exosomes compared to other isolated microvesicles

A2. Thank you for your detailed feedback. We have made every effort to enhance the manuscript in this revised version, ensuring that our conclusions are grounded in solid evidence and that they avoid any speculation.

My main concerns with the manuscript:

Q3. The authors demonstrate that microvesicles contain the most mtDNA, however, they also demonstrate that only isolated exosomes influence embryo respiration. These are two separate populations of extracellular vesicles.

A3. This manuscript focuses on the DNA content secreted by the endometrium and captured by the embryo. We identified both mitochondrial DNA and genomic DNA. We have found that mitochondrial DNA is predominantly secreted and encapsulated within microvesicles, while all three types of vesicles encapsulate genomic DNA. Specifically, based on the results we presented in Response A8 to the reviewers and included in the latest version of the manuscript, we observed that exosomes contain the highest amount of genomic DNA. Furthermore, exosomes have the greatest impact on embryo bioenergetics, suggesting that this DNA content may primarily exert this effect. We have thoroughly revised the manuscript, focusing our message on DNA content.

Q4. mtDNA is not specifically identified as being taken up by embryos only DNA.

A4. We agree with the reviewer; as we mention in answer A9, EdU does not specifically label mitochondrial DNA. To solve this issue, we incubated a synthetic molecule of labeled mtDNA with embryos and analyzed mtDNA incorporation using confocal microscopy. We co-cultured hatched mouse embryos (3.5 days) with an ATP8 sequence conjugated with Biotin overnight at 37ºC and 5% CO2. We then permeabilized embryos, incubated them with Streptavidine-Cy3 for 45 min, and visualized the results using an SP8 confocal microscope (Leica). We observed mtDNA internalization by cells of the hatched embryos; please see new supplementary Figure 7 and lines 234-237 on page 9 and lines 583-592 M&M on page 21.

Q5. The authors do not rule out that other components packaged in extracellular vesicles could be the factors influencing embryo metabolism.

A5. The vesicular subtypes contain molecules beyond DNA, such as microRNAs, proteins, or lipids. Our laboratory has studied the transmission of vesicles and their relationship with their contents (particularly microRNAs) and their connection to maternal-fetal communication. In this study, we focused on genomic/mitochondrial DNA. We cannot exclude the possibility that other molecules may influence metabolism; this statement is already noted in the discussion section on lines 328-331 on page 12.

Q6. Taken together, these concerns seem to contradict the implication of the title of the manuscript – the authors do not demonstrate that inheritance of maternal mtDNA has a direct causative effect on embryo metabolism.

A6. We have modified the title to better align with the manuscript’s results. The proposed new title for the manuscript is “Vertical transmission of maternal DNA through extracellular vesicles modulates embryo bioenergetics during the periconceptional period.”

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for The Authors):

Q7. Would it be possible to validate the mtDNA content and mitophagy activity in different periods using the Ishikawa cells?

A7. Unfortunately, this validation cannot be achieved with in vitro cultures of cell lines, especially with a cell line such as the endometrial adenocarcinoma-derived Ishikawa cell line. While mimicking the menstrual cycle (as observed in Figure 3 of the manuscript) is entirely artificial, we believe that the statistically significant results obtained in human samples faithfully represent the biological processes involved. Using a cell line, in our opinion, would not provide us with novel information.

Q8. Characterization of the EVs subpopulations from Ishikawa cells and direct evidence to show the EdU labeled DNA is contained in the EVs are necessary.

A8. To address this concern, we designed a novel experiment. We cultured Ishikawa cells in the presence of Edu, isolated the three types of vesicles, and evaluated labeled DNA content by flow cytometry (as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 5). All three types of vesicles exhibited positive EdU-DNA labeling; notably, the exosomal fraction demonstrated substantially higher DNA content than the other vesicle populations. Please see new supplementary Figure 5 and lines 217-218 on page 9, and lines 576-582 of the M&M on pages 20-21.

Q9. Would EdU incorporate into the genomic DNA or mitochondrial DNA?

A9. EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) is a nucleoside analog of thymidine and becomes incorporated into DNA during active DNA synthesis. EdU labels all newly synthesized DNA, both genomic and mitochondrial; however, we cannot differentiate between them with this technique.

Q10. It is difficult to assess whether the EV-derived DNA was taken by the TE or ICM without immunostaining of cell lineage markers in mouse embryos.

A10. We did not aim to label the inner cell mass, as the vesicles primarily enter through trophectodermal cells. The images presented in Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 5 depict trophectoderm cells.

Q11. It is also valuable to perform co-staining of Mitotracker to show the co-localization of EdU labelled DNA and the mitochondrial.

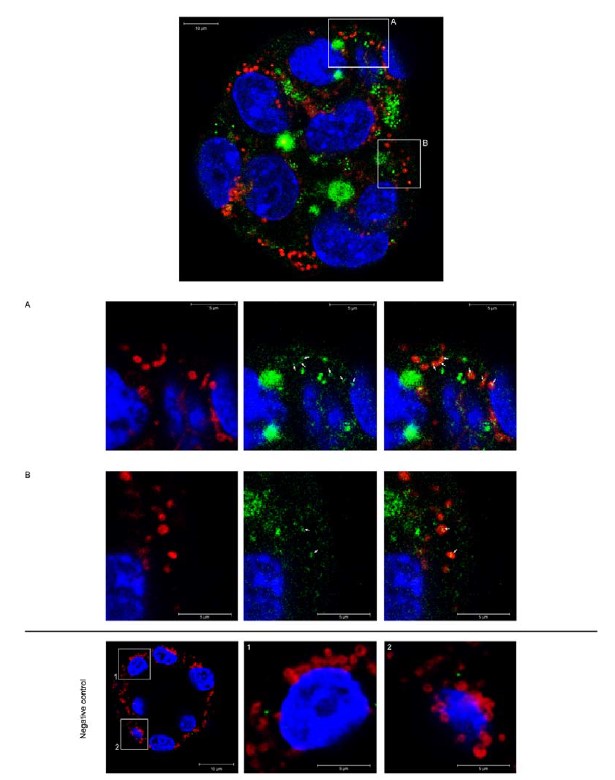

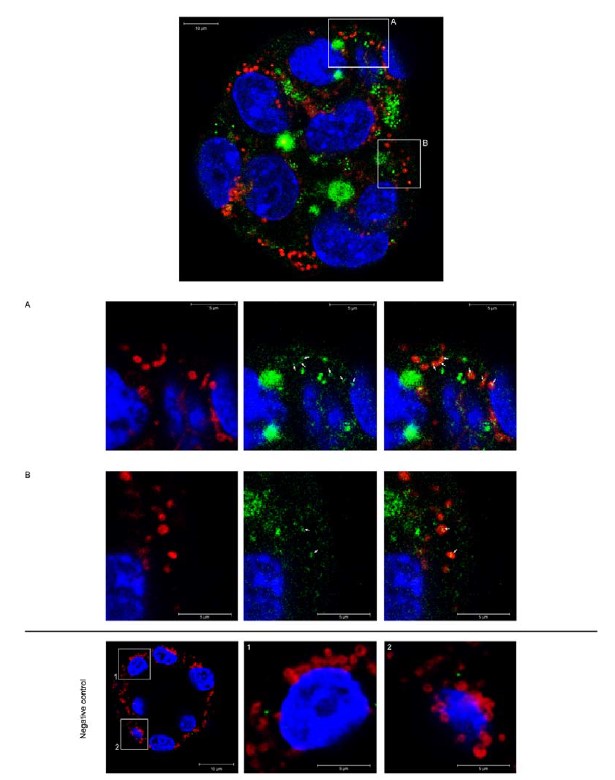

A11. Per the reviewer's suggestion, we conducted an experiment as described in the following text. We isolated MVs from the culture media of EdU-treated Ishikawa cells and co-incubated them with embryos overnight. The resulting images (See Author response image 1) show an embryo subjected to staining with EdU-tagged DNA labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (green), Mitotracker Deep Red (red), and nuclei (blue). Detailed views of the embryo are presented in panels A and B. Notably, we observed co-localization of mitochondria and EdU-tagged DNA, as indicated by the white arrows. Despite this intriguing finding, we chose not to include these results in the initial version of the manuscript; however, if the editor deems it appropriate, we would be delighted to incorporate them into the final version. The experimental procedure for co-localization of EdU DNA-tagged with mitochondria involved the following steps: Mitotracker Deep Red FM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, M22426) was added to the embryo media at a final concentration of 200 nM, and the embryos were subsequently incubated for 45-60 minutes prior to fixation.

Author response image 1.

Co-localization of mitochondria and EdU-tagged DNA in mouse embryos. Representative micrograph of an embryo co-incubated with MVs isolated from the culture media of Ishikawa cells treated with EdU. EdU-tagged DNA was labeled with Alexa Fluro 488 (green). Mitotracker Deep Red (mitochondria; red) and nuclei (blue). A and B) magnified images of the embryo show detailed co-localization of mitochondria and EdU-tagged DNA (white arrows). Negative control) Embryos incubated with MVs isolated from control Ishikawa cells (without EdU incubation) and stained with the click-it reaction cocktail. A and B showed magnified images of the embryo. Notice the absence of EdU-Alexa Fluro 488 signals (green).

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for The Authors):

Q12. It would be helpful if the authors could provide citations and rationale for why they chose specific molecular markers to validate the different population of extracellular vesicles.

A12. Different extracellular populations are defined by molecular marker signatures that reflect their origin.

VDAC1 forms ionic channels in the mitochondrial membrane, has a role in triggering apoptosis, and has been described as characteristic of ABs.[1]

The ER protein Calreticulin has also been used as an AB marker [2]; however, other studies have noted the presence of Calreticulin in MVs. [1] This apparent non-specificity may derive from apoptotic processes, during which the ER membrane fragments and forms vesicles smaller than ABs, which would contain Calreticulin and sediment at higher centrifugal forces.[3,4] In fact, proteomic studies have linked the presence of Calreticulin with vesicular fractions of a size range relevant for MVs [5] and ABs [6].

ARF6, a GTP-binding protein implicated in cargo sorting and promoting MV formation, has been proposed as an MV marker. [7,8]

Classic markers of EXOs include molecules involved in biogenesis, such as tetraspanins (CD63, CD9, CD81), Alix, TSG101, and flotillin-1.[9,10] Nonetheless, studies have recently reported the widespread nature of such markers among various EV populations, although with different relative abundances (such as is the case for CD9, CD63, HSC70, and flotillin-1[11]). Notably, certain molecular markers (such as TSG101[1,11]) have been ratified as specific to EXOs.

References

D. K. Jeppesen, M. L. Hvam, B. Primdahl-Bengtson, A. T. Boysen, B. Whitehead, L. Dyrskjøt, T. F. Orntoft, K. A. Howard, M. S. Ostenfeld, J. Extracell. Vesicle. 2014, 3, 25011, doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.25011.

J. van Deun, P. Mestdagh, R. Sormunen, V. Cocquyt, K. Vermaelen, J. Vandesompele, M. Bracke, O. De Wever, A. Hendrix, J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2014, 3:24858, doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.24858.

L. Abas, C. Luschnig, Anal. Biochem. 2010, 401, 217-227, doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.02.030.

C. Lavoie, J. Lanoix, F. W. Kan, J. Paiement, J. Cell Sci. 1996, 109(6), 1415-1425.

M. Tong, T. Kleffmann, S. Pradhan, C. L. Johansson, J. DeSousa, P. R. Stone, J. L. James, Q. Chen, L. W. Chamley, Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31(4), 687-699, doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew004.

P. Pantham, C. A. Viall, Q. Chen, T. Kleffmann, C. G. Print, L. W. Chamley, Placenta. 2015, 36, 1463e1473, doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.10.006.

V. Muralidharan-Chari, J. Clancy, C. Plou, M. Romao, P. Chavrier, G. Raposo, C. D'Souza-Schorey, Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1875-1885.

C. Tricarico, J. Clancy, C. D'Souza-Schorey, Small GTPases. 2016, 0(0), 1-13.

M. Colombo, G. Raposo, C. Théry, Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255-289, doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326.

S. Mathivanan, H. Ji, R. J. Simpson, J. Proteomics. 2010, 73(10), 1907-1920.

J. Kowal, G. Arras, M. Colombo, M. Jouve, J. P. Morath, B. Primdal-Bengtson, F. Dingli, D. Loew, M. Tkach, C. Théry, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113(8), E968-77.

Q13. The PCA analysis in supplementary figure 4 A&B needs more explanation for why they think separation of the two conditions based on principal component 1 is sufficient. The small number of replicates makes me concerned because principal component 2 does not show similarity of replicates for the DNase treated samples. Also, 4C has no description in the figure legend.

A13. The PCA results show a clear separation between the two conditions; we believe this separation is primarily driven by the differences observed in principal component 1 (PC1). We would like to address the concerns raised by the reviewer with the following points:

Interpretation of PCs: In PCA, the principal components represent orthogonal axes capturing the highest variance in the data. PC1 accounts for 56% and 57% of the variance in the two conditions, respectively. The significant variance explained by PC1 suggests that it effectively captures the major sources of variation between the samples.

Sample Replicates and Variability: The concern regarding the small number of replicates is acknowledged, and we understand its impact on the analysis. Despite the limited number of replicates, the consistent pattern of separation in PC1 between the two conditions provides confidence in the observed separation. We also agree that PC2 does not show an apparent similarity among the DNase-treated samples; however, this does not diminish the significance of PC1, which robustly separates the two conditions.

We include the Figure legend for 4C: “C) Principal component analysis shows EV sample grouping due to specificity in coding-gene sequences.

Q14. I am confused by the phrasing in the last two sentences of the top paragraph on page 7. Why would apoptotic bodies all have similar content if they encapsulate a greater amount of material making their contents less specific? Please clarify.

A14. This sentence intended to convey the fact that apoptotic bodies (ABs) are formed from apoptotic cells, they are larger in size, and their content is more non-specific - this non-specific nature arises as they do not encapsulate molecules specifically, unlike the other two types of vesicles. For more detailed information on ABs in human reproduction, we published an extensive review in 2018 (see below).

Simon C, Greening DW, Bolumar D, Balaguer N, Salamonsen LA, Vilella F. Extracellular Vesicles in Human Reproduction in Health and Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2018 Jun 1;39(3):292-332. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00229. PMID: 29390102.

Q15. The first and last sentences of the last paragraph of page 8 seem to contradict each other. Please clarify.

A15. We observe an enrichment in the amount of mitochondrial DNA in samples during the receptive and post-receptive phases. While the data may not show statistical significance, we observed a trend towards greater enrichment in receptivity compared to pre-receptivity. The lack of significant differences could be attributed to inherent variability among patients. We have also altered the text on page 8 to avoid confusion.

Q16. Quantification of the rates of DNA incorporation into embryos would strengthen Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 5.

A16. We acknowledge the reviewer's feedback, and in response, we conducted an assay to quantify the total DNA incorporated into the embryos. We isolated EVs from the control Ishikawa cell culture media and EdU-treated Ishikawa cell culture media to achieve this. Subsequently, we co-incubated both types of EVs with ten embryos overnight in G2 plus media at 37ºC and 5% CO2.

After co-incubation, we collected embryos and the culture media containing co-incubated EVs. We then isolated total DNA using the QIAamp® DNA Mini kit (Qiagen; 51304). To label the EdU-DNA particles, we performed a click-it reaction using the Click-iT™ EdU Alexa Fluor™ 488 flow cytometry assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ref: C10420) per the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, we cleaned and purified DNA using AMPure beads XP (Beckman Coulter, A63882) and eluted DNA in 150 L of 0.1 M Tris-EDTA. Finally, we measured the fluorescence of each sample using a Victor3 plate reader (PerkinElmer). To ensure accuracy, we subtracted the background signal from non-labeled DNA-derived EVs and embryos incubated without EVs for each sample. Despite conducting the experiment twice, we encountered challenges in obtaining clear results, possibly due to the limitation of the technique's resolution.

Q17. If mtDNA is most enriched in MVs but only embryos cultured with Exos demonstrated differences in respiration the authors need to comment on this discrepancy.

A17. We ask the reviewer to refer to Answer A3; we have thoroughly revised the manuscript, focusing our message on DNA content.

Q18. The authors should change the definitive language in the title of the manuscript because all evidence presented is correlative.

A18.We have modified the title to better align with the manuscript's results. The proposed new title for the manuscript is “Vertical transmission of maternal DNA through extracellular vesicles modulates embryo bioenergetics during the periconceptional period.”

Q19. I realize this is beyond what the authors intend for the scope of this paper, however, on page 6 the authors describe membranous structures within the ABs but say they couldn't study their presence with organelle-specific markers. Why? Presence of organelles in these vesicles is very interesting!

A19. As the reviewer rightly points out, we did not study ABs in this manuscript. Analysis of the electron microscopy images suggests the presence of fragments of organelles, most likely originating from apoptotic processes; however, we did not use any specific markers to confirm our assertion. We have modified the text to avoid any confusion. Please see Page 6, Lines 120-121, for further details.