Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorWenfeng QianChinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- Senior EditorDetlef WeigelMax Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

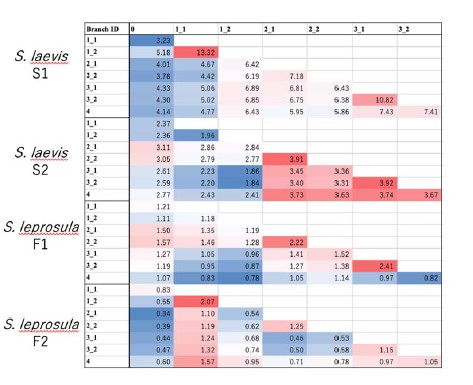

In this study, Satake and colleagues endeavored to explore the rates and patterns of somatic mutations in wild plants, with a focus on their relationship to longevity. The researchers examined slow- and fast-growing tropical tree species, demonstrating that slow-growing species exhibited five times more mutations than their fast-growing counterparts. The number of somatic mutations was found to increase linearly with branch length. Interestingly, the somatic mutation rate per meter was higher in slow-growing species, but the rate per year remained consistent across both species. A closer inspection revealed a prevalence of clock-like spontaneous mutations, specifically cytosine-to-thymine substitutions at CpG sites. The author suggested that somatic mutations were identified as neutral within an individual, but subject to purifying selection when transmitted to subsequent generations. The authors developed a model to assess the influence of cell division on mutational processes, suggesting that cell-division independent mutagenesis is the primary mechanism.

The authors have gathered valuable data on somatic mutations, particularly regarding differences in growth rates among trees. Their meticulous computational analysis led to fascinating conclusions, primarily that most somatic mutations accumulate in a cell-division independent manner. The discovery of a molecular clock in somatic mutations significantly advances our comprehension of mutational processes that may generate genetic diversity in tropical ecosystems. The interpretation of the data appears to be based on the assumption that somatic mutations can be effectively transmitted to the next generation unless negative selection intervenes. However, accumulating evidence suggests that plants may also possess "effective germlines," which could render the somatic mutations detected in this study non-transmittable to progeny. Incorporating additional analyses/discussion in the context of plant developmental biology, particularly recent studies on cell lineage, could further enhance this study.

Specifically, several recent studies address the topics of effective germline in plants. For instance, Robert Lanfear published an article in PLoS Biology exploring the fundamental question, "Do plants have a segregated germline?" A study in PNAS posited that "germline replications and somatic mutation accumulation are independent of vegetative life span in Arabidopsis." A phylogenetic-based analysis titled "Rates of Molecular Evolution Are Linked to Life History in Flowering Plants" discovered that "rates of molecular evolution are consistently low in trees and shrubs, with relatively long generation times, as compared with related herbaceous plants, which generally have shorter generation times." Another compelling study, "The architecture of intra-organism mutation rate variation in plants," published in PLoS Biology, detected somatic mutations in peach trees and strawberries. Although some of these studies are cited in the current work, a deeper examination of the findings in relation to the existing literature would strengthen the interpretation of the data.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, the authors used an original empirical design to test if somatic mutation rates are different depending on the plant growth rates. They detected somatic mutations along the growth axes of four trees - two individuals per species for two dipterocarp tree species growing at different rates. They found here that plant somatic mutations are accumulated are a relatively constant rate per year in the two species, suggesting that somatic mutation rates correlate with time rather than with growth, i.e. the number of cell divisions. The authors then suggest that this result is consistent with a low relative contribution of DNA replication errors (referred to as α in the manuscript) to the somatic mutation rates as compared to the other sources of mutations (β). Given that plants - in particular, trees - are generally assumed to deviate from the August Weismann's theory (a part of the somatic variation is expected to be transmitted to the next generation), this work could be of interest for a large readership interested by mutation rates as a whole, since it has implications also for heritable mutation rates too. In addition, even if this is not discussed, the putatively low contribution of DNA replication errors could help to understand the apparent paradox associated to trees. Indeed, trees exhibit clear signatures of lower molecular evolution (Lanfear et al. 2013), therefore suggesting lower mutation rates per unit of time. Trees could partly keep somatic mutations under control thanks to a long-term evolution towards low α values, resulting in low α/β ratios as compared to short-lived species. I therefore consider that the paper tackles a fundamental albeit complex question in the field.

Overall, I consider that the authors should clearly indicate the weaknesses of the studies. For instance, because of the bioinformatic tools used, they have reasonably detected a small part of the somatic mutations, those that have reached a high allele frequency in tissues. Mutation counts are known to be highly dependent on the experimental design and the methods used. Consequently, (i) this should be explicit and (ii) a particular effort should be made to demonstrate that the observed differences in mutation counts are robust to the potential experimental biases. This is important since, empirically, we know how mutation counts can vary depending on the experimental designs. For instance, a difference of an order of magnitude has been observed between the two papers focusing on oaks (Schmid-Siegert et al. 2017 and Plomion et al. 2018) and this difference is now known to be due to the differences in the experimental designs, in particular the sequencing effort (Schmitt et al. 2022).

Having said that, my overall opinion is that (i) the authors have worked on an interesting design and generated unique data, (ii) the results are probably robust to some biases and therefore strong enough (but see my comments regarding possible improvements), (iii) the interpretations are reasonable and (iv) the discussion regarding the source of somatic mutations is valuable (even if I also made some suggestions here also).

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In animals, several recent studies have revealed a substantial role for non-replicative mutagenic processes such as DNA damage and repair rather than replicative error as was previously believed. Much less is known about how mutation operates in plants, with only a handful of studies devoted to the topic. Authors Satake et al. aimed to address this gap in our understanding by comparing the rates and patterns of somatic mutation in a pair of tropical tree species, slow-growing Shorea lavis and fast-growing S. leprosula. They find that the yearly somatic mutation rates in the two species is highly similar despite their difference in growth rates. The authors further find that the mutation spectrum is enriched for signatures of spontaneous mutation and that a model of mutation arising from different sources is consistent with a large input of mutation from sources uncorrelated with cell division. The authors conclude that somatic mutation rates in these plants appears to be dictated by time, not cell division numbers, a finding that is in line with other eukaryotes studied so far.

In general, this work shows careful consideration and study design, and the multiple lines of evidence presented provide good support for the authors' conclusions. In particular, they use a sound approach to identify rare somatic mutations in the sampled trees including biological replicates, multiple SNP-callers and thresholds, and without presumption of a branching pattern.

Inter-species comparisons of absolute mutation rates is challenging. This is largely due to differences in SNP-calling methods and reference genome quality leading to variable sensitivity and specificity in identifying mutations. By applying their pipeline consistently across both species, the authors provide confidence in the comparative mutation rate results. Moreover, the presented false negative and false positive rate estimates for each species would apparently have minimal impact on the overall findings.

Despite the overall elegance of the authors' experimental setup, one methodological wrinkle warrants consideration. The authors compare the mutation rate per meter of growth, demonstrating that the rate is higher in slow-growing S. laevis: a key piece of evidence in favor of the authors' conclusion that somatic mutations track absolute time rather than cell division. To estimate the mutation rate per unit distance, they regress the per base-pair rate of mutations found between all pairwise branch tips against the physical distance separating the tips (Fig. 2a). While a regression approach is appropriate, the narrowness of the confidence interval is overstated as the points are not statistically independent: internal branches are represented multiple times. (For example, all pairwise comparisons involving a cambium sample will include the mutations arising along the lower trunk.) Regressing rates and lengths of distinct branches might be more appropriate. Judging from the data presented, however, the point estimates seem unlikely to change much.

This work deepens our understanding of how mutation operates at the cellular level by adding plants to the list of eukaryotes in which many mutations appear to derive from non-replicative sources. Given these results, it is intriguing to consider whether there is a fundamental mechanism linking mutation across distantly related species. Plants, generally, present a unique opportunity in the study of mutation as the germline is not sequestered, as it is in animals, and thus the forces of both mutation and selection acting throughout an individual plant's life could in principle affect the mutations transmitted to seed. The authors touch on this aspect, finding no evidence for a reduction in non-synonymous somatic mutations relative to the background rate, but more work-both experimental and observational-is needed to understand the dynamics of mutation and cell-competition within an individual plant. Overall, these results open the door to several intriguing questions in plant mutation. For example, is somatic mutation age-dependent in other species, and do other tropical plants harbor a high mutation rate relative to temperate genera? Any future inquiries on this topic would benefit from modeling their approach for identifying somatic mutations on the methods laid out here.