Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Weaknesses:

- The authors should better review what we know of fungal Drosophila microbiota species as well as the ecology of rotting fruit. Are the microbiota species described in this article specific to their location/setting? It would have been interesting to know if similar species can be retrieved in other locations using other decaying fruits. The term 'core' in the title suggests that these species are generally found associated with Drosophila but this is not demonstrated. The paper is written in a way that implies the microbiota members they have found are universal. What is the evidence for this? Have the fungal species described in this paper been found in other studies? Even if this is not the case, the paper is interesting, but there should be a discussion of how generalizable the findings are.

The reviewer inquires as to whether the microbial species described in this article are ubiquitously associated with Drosophila or not. Indeed, most of the microbes described in this manuscript are generally recognized as species associated with Drosophila spp. For example, species such as Hanseniaspora uvarum, Pichia kluyveri, and Starmerella bacillaris have been detected in or isolated from Drosophila spp. collected in European countries as well as the United States and Oceania (Chandler et al., 2012; Solomon et al., 2019). As for the bacteria, species belonging to the genera Pantoea, Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, and Acetobacter have also previously been detected in wild Drosophila spp. (Chandler et al., 2011). These elucidations will be incorporated into our revised manuscript.

Nevertheless, the term “core” in the manuscript title may lead to misunderstanding, as the generality does not ensure the ubiquitous presence of these microbial species in every individual fly. Considering this point, we will replace the term with an expression more appropriate to our context.

- Can the authors clearly demonstrate that the microbiota species that develop in the banana trap are derived from flies? Are these species found in flies in the wild? Did the authors check that the flies belong to the D. melanogaster species and not to the sister group D. simulans?

Can the authors clearly demonstrate that the microbiota species that develop in the banana trap are derived from flies? Are these species found in flies in the wild?

The reviewer asked whether the microbial species identified in the fermented banana samples were derived from flies. To address this question, additional experiments under more controlled conditions, such as the inoculation of specific species of wild flies onto fresh bananas, would be needed. Nevertheless, the microbes may potentially originate from wild flies, as supported by the literature cited in our response to the Weakness 1).

Alternative sources for microbial provenance also merit consideration. For example, microbial entities may be inherently present in unfermented bananas through the infiltration of peel injuries (lines 1141-1142 of the original manuscript). In addition, they could be introduced by insects other than flies, given that both rove beetles (Staphylinidae) and sap beetles (Nitidulidae) were observed in some of the traps. These possibilities will be incorporated into the 'MATERIALS AND METHODS' and 'DISCUSSION' sections of our revised manuscript.

Did the authors check that the flies belong to the D. melanogaster species and not to the sister group D. simulans?

Our sampling strategy was designed to target not only D. melanogaster but also other domestic Drosophila species, such as D. simulans, that inhabit human residential areas. After adult flies were caught in each trap, we identified the species as shown in Table S1, thereby showing the presence of either or both D. melanogaster and D. simulans. We will provide these descriptions in MATERIALS AND METHODS and DISCUSSION.

- Did the microarrays highlight a change in immune genes (ex. antibacterial peptide genes)? Whatever the answer, this would be worth mentioning. The authors described their microarray data in terms of fed/starved in relation to the Finke article. They should clarify if they observed significant differences between species (differences between species within bacteria or fungi, and more generally differences between bacteria versus fungi).

Did the microarrays highlight a change in immune genes (ex. antibacterial peptide genes)? Whatever the answer, this would be worth mentioning.

Regarding the antimicrobial peptide genes, statistical comparisons of our RNA-seq data across different conditions were impracticable because most of them showed low expression levels (refer to Author response table 1, which exhibits the RNA-seq data of the yeast-fed larvae; similar expression profiles were observed in the bacteria-fed larvae). While a subset of genes exhibited significantly elevated expression in the non-supportive conditions relative to the supportive ones, this can be due to intra-sample variability rather than due to distinct nutritional environments. Therefore, it would be difficult to discuss a change in immune genes in the paper. Additionally, the previous study that conducted larval microarray analysis (Zinke et al., 2002) did not explicitly focus on immune genes.

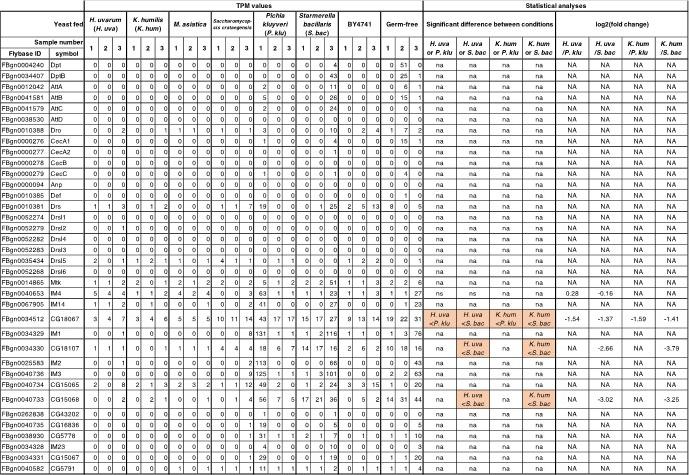

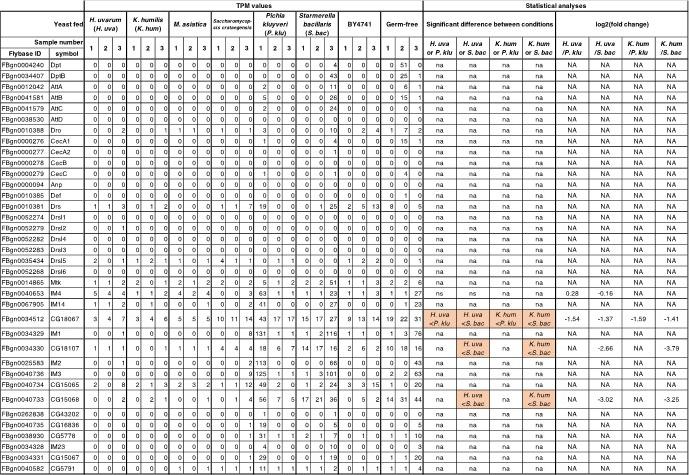

Author response table 1.

Antimicrobial peptide genes are not up-regulated by any of the microbes. Antimicrobial peptides gene expression profiles of whole bodies of first-instar larvae fed on yeasts. TPM values of all samples and comparison results of gene expression levels in the larvae fed on supportive and non-supportive yeasts are shown. Antibacterial peptide genes mentioned in Hanson and Lemaitre, 2020 are listed. NA or na, not available.

They should clarify if they observed significant differences between species (differences between species within bacteria or fungi, and more generally differences between bacteria versus fungi).

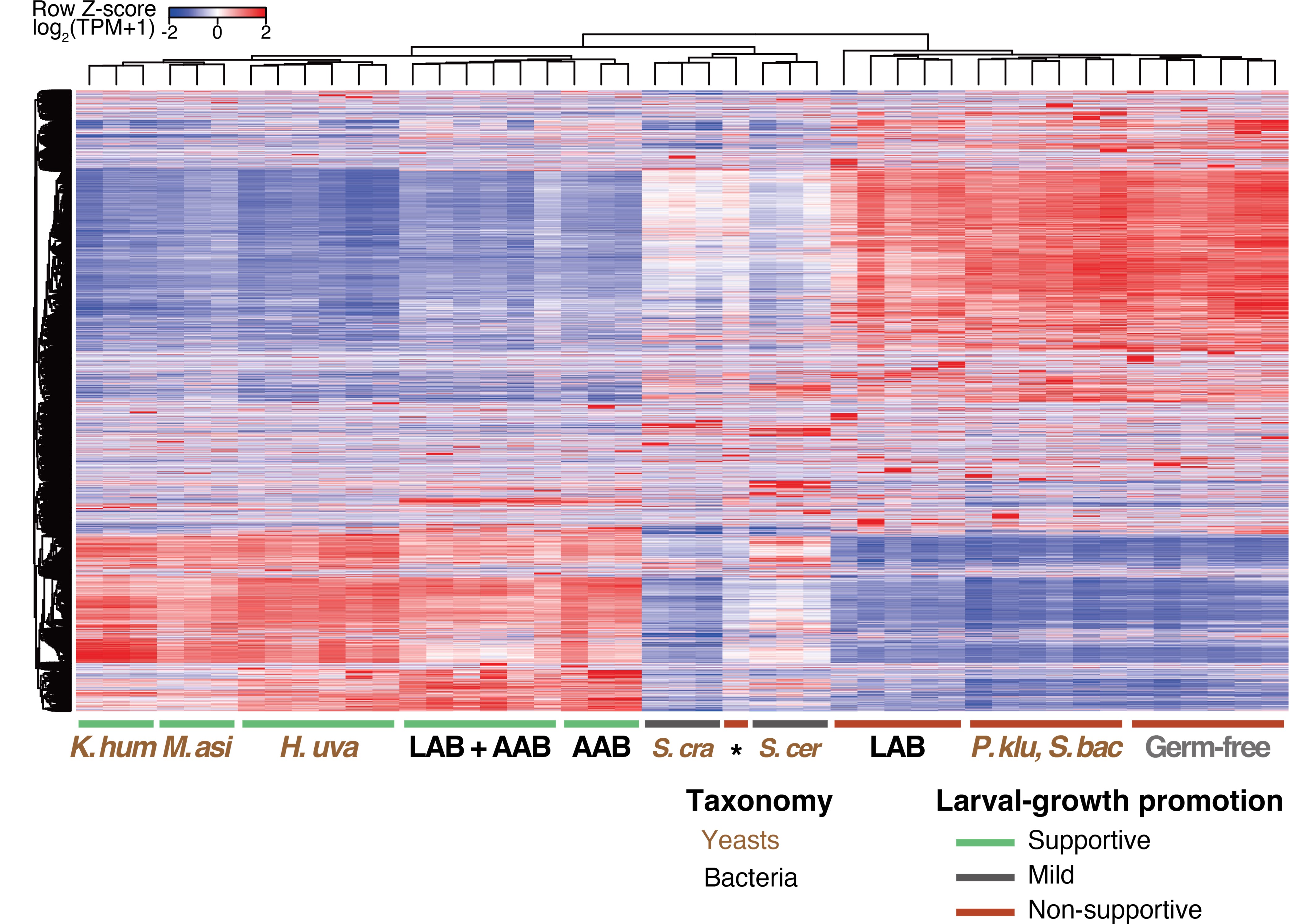

We did not observe significant differences between species within bacteria or fungi, or between bacteria and fungi. For example, the gene expression profiles of larvae fed on the various supporting microbes showed striking similarities to each other, as evidenced by the heat map showing the expression of all genes detected in larvae fed either yeast or bacteria (Author response image 1). Similarities were also observed among larvae fed on distinct non-supporting microbes.

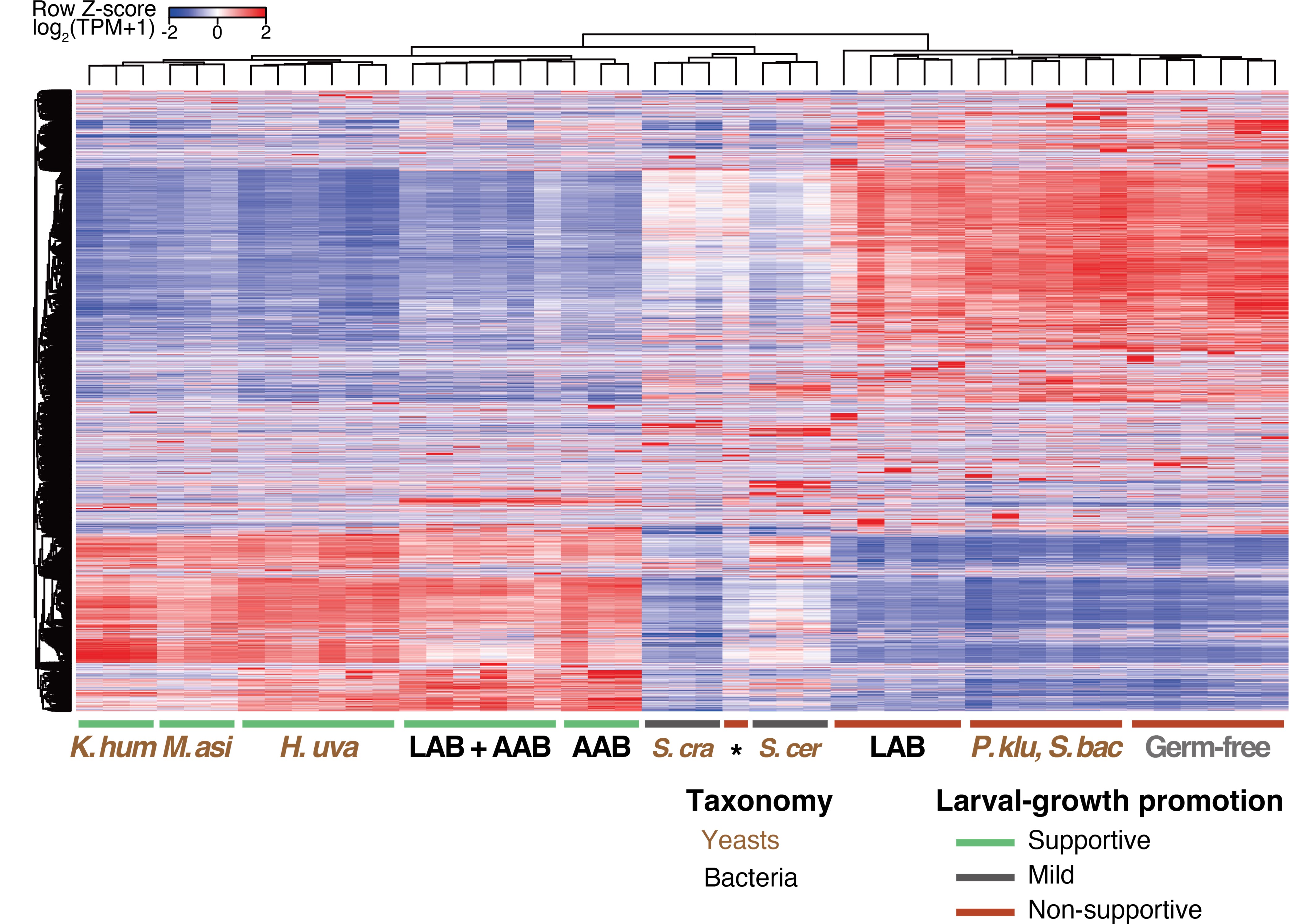

Author response image 1.

Gene expression profiles of larvae fed on the various supporting microbes show striking similarities to each other. Heat map showing the gene expression of the first-instar larvae that fed on yeasts or bacteria. Freshly hatched germ-free larvae were placed on banana agar inoculated with each microbe and collected after 15 h feeding to examine gene expression of the whole body. Note that data presented in Figures 3A and 4C in the original manuscript, which are obtained independently, are combined to generate this heat map. The labels under the heat map indicate the microbial species fed to the larvae, with three samples analyzed for each condition. The lactic acid bacteria (“LAB”) include Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Leuconostoc mesenteroides, while the lactic acid bacterium (“AAB”) represents Acetobacter orientalis. “LAB + AAB” signifies mixtures of the AAB and either one of the LAB species. The asterisk in the label highlights a sample in a “LAB” condition (Leuconostoc mesenteroides), which clustered separately from the other “LAB” samples. Brown abbreviations of scientific names are for the yeast-fed conditions. H. uva, Hanseniaspora uvarum; K. hum, Kazachstania humilis; M. asi, Martiniozyma asiatica; S. cra, Saccharomycopsis crataegensis; P. klu, Pichia kluyveri; S. bac, Starmerella bacillaris; S. cer, S. cerevisiae BY4741 strain.

Only a handful of genes showed different expression patterns between larvae fed on yeast and those fed on bacteria, without any enrichment for specialized gene functions. Thus, it is challenging to discuss the potential differential impacts, if any, of yeast and bacteria on larval growth.

- The whole paper - and this is one of its merits - points to a role of the Drosophila larval microbiota in processing the fly food. Are these bacterial and fungal species found in the gut of larvae/adults? Are these species capable of establishing a niche in the cardia of adults as shown recently in the Ludington lab (Dodge et al.,)? Previous studies have suggested that microbiota members stimulate the Imd pathway leading to an increase in digestive proteases (Erkosar/Leulier). Are the microbiota species studied here affecting gut signaling pathways beyond providing branched amino acids?

The whole paper - and this is one of its merits - points to a role of the Drosophila larval microbiota in processing the fly food. Are these bacterial and fungal species found in the gut of larvae/adults? Are these species capable of establishing a niche in the cardia of adults as shown recently in the Ludington lab (Dodge et al.,)?

Although we did not investigate the microbiota in the gut of either larvae or adults, we did compare the microbiota within surface-sterilized larvae or adults with those in food samples. We found that adult flies and early-stage food sources, as well as larvae and late-stage food sources, harbor similar microbial species (Figure 1F). Additionally, previous examinations of the gut microbiota in wild adult flies have identified microbial species or taxa congruent with those we isolated from our foods (Chandler et al., 2011; Chandler et al., 2012). We have elaborated on this in our response to Weakness 1).

While we did not investigate whether these species are capable of establishing a niche in the cardia of adults, we will cite the study by Dodge et al., 2023 in our revised manuscript and discuss the possibility that predominant microbes in adult flies may show a propensity for colonization.

Previous studies have suggested that microbiota members stimulate the Imd pathway leading to an increase in digestive proteases (Erkosar/Leulier). Are the microbiota species studied here affecting gut signaling pathways beyond providing branched amino acids?

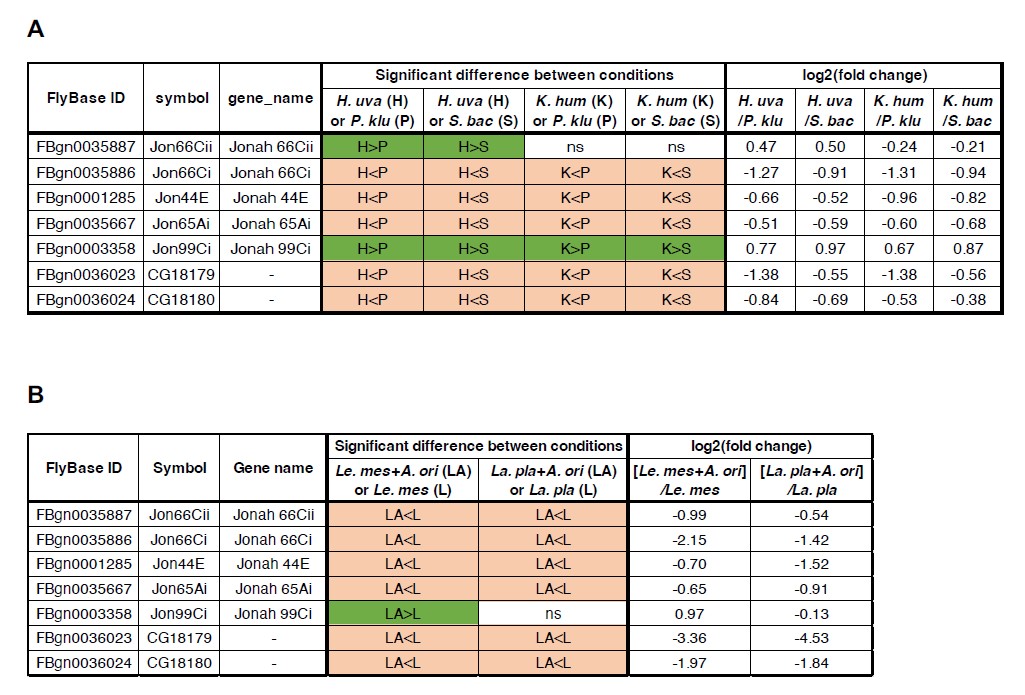

The reviewer inquires whether the supportive microbes in our study stimulate gut Imd signaling pathways and induce the expression of digestive protease genes, as demonstrated in a previous study (Erkosar et al., 2015). According to our RNA-seq data, it seems unlikely that the supportive microbes stimulate the signaling pathway. Figures contained in Author response image 2 provide the statistical comparisons of expression levels for seven protease genes between the supportive and the non-supportive conditions. These genes did not exhibit a consistent upregulation in the presence of the supportive microbes (H. uva or K. hum in Author response image 2A; Le mes + A. ori in Author response image 2B). Rather, they exhibited a tendency to be upregulated under the non-supportive microbes (St. bac or Pi. klu in Author response image 2A; La. pla in Author response image 2B).

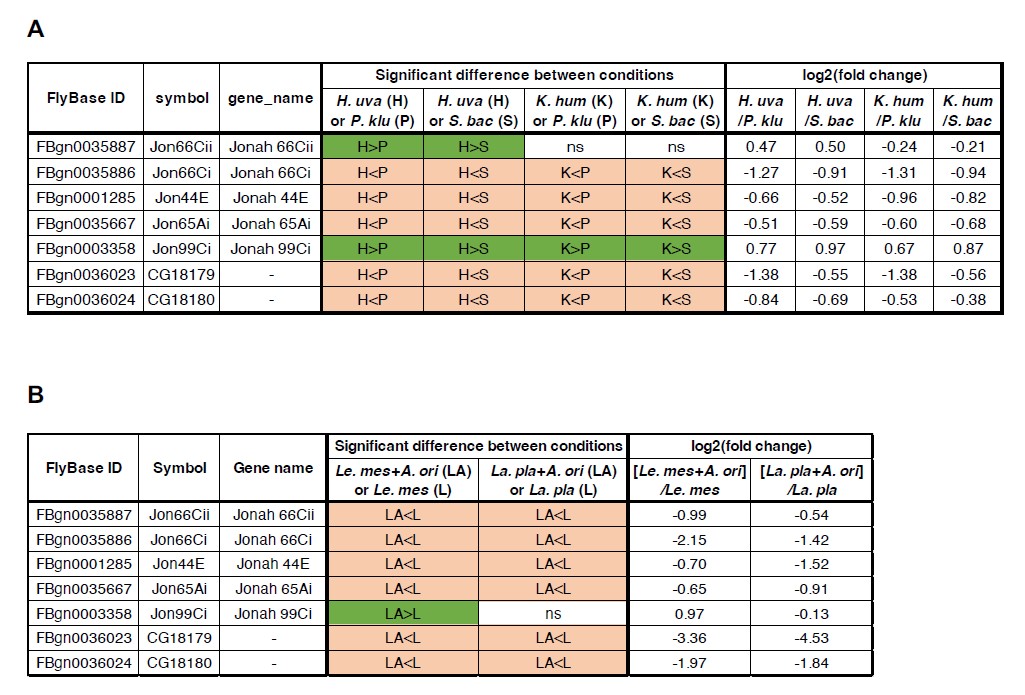

Author response image 2.

Most of the peptidase genes reported by Erkosar et al., 2015 are more highly expressed under the non-supportive conditions than the supportive conditions. Comparison of the expression levels of seven peptidase genes derived from the RNA-seq analysis of yeast-fed (A) or bacteria-fed (B) first-instar larvae. A previous report demonstrated that the expression of these genes is upregulated upon association with a strain of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, and that the PGRP-LE/Imd/Relish signaling pathway, at least partially, mediates the induction (Erkosar et al., 2015). H. uva, Hanseniaspora uvarum; K. hum, Kazachstania humilis; P. klu, Pichia kluyveri; S. bac, Starmerella bacillaris; La. pla, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum; Le. mes, Leuconostoc mesenteroides; A. ori, Acetobacter orientalis; ns, not significant.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Weaknesses:

The experimental setting that, the authors think, reflects host-microbe interactions in nature is one of the key points. However, it is not explicitly mentioned whether isolated microbes are indeed colonized in wild larvae of Drosophila melanogaster who eat bananas. Another matter is that this work is rather descriptive and a few mechanical insights are presented. The evidence that the nutritional role of BCAAs is incomplete, and molecular level explanation is missing in "interspecies interactions" between lactic acid bacteria (or yeast) and acetic acid bacteria that assure their inhabitation. Apart from these matters, the future directions or significance of this work could be discussed more in the manuscript.

The experimental setting that, the authors think, reflects host-microbe interactions in nature is one of the key points. However, it is not explicitly mentioned whether isolated microbes are indeed colonized in wild larvae of Drosophila melanogaster who eat bananas.

The reviewer asks whether the isolated microbes were colonized in the larval gut. Previous studies on microbial colonization associated with Drosophila have predominantly focused on adults (Pais et al. PLOS Biology, 2018), rather than larval stages. Developing larvae continually consume substrates which are already subjected to microbial fermentation and abundant in live microbes until the end of the feeding larval stage. Therefore, we consider it difficult to discuss microbial colonization in the larval gut. We will add this point in the DISCUSSION of the revised manuscript.

Another matter is that this work is rather descriptive and a few mechanical insights are presented. The evidence that the nutritional role of BCAAs is incomplete, and molecular level explanation is missing in "interspecies interactions" between lactic acid bacteria (or yeast) and acetic acid bacteria that assure their inhabitation.

While recognizing the importance of comprehensive mechanistic analysis, this study includes all experimentally feasible data. Elucidation of more detailed molecular mechanisms lies beyond the scope of this study and will be the subject of future research.

Regarding the nutritional role of BCAAs, the incorporation of BCAAs enabled larvae fed with the non-supportive yeast to grow to the second instar. This observation suggests that consumption of BCAAs upregulates diverse genes involved in cellular growth processes in larvae. We have discussed the hypothetical interaction between lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and acetic acid bacteria (AAB) in the manuscript (lines 402-405): LAB may facilitate lactate provision to AAB, consequently enhancing the biosynthesis of essential nutrients such as amino acids. To test this hypothesis, future experiments will include the supplementation of lactic acid to AAB culture plates and the co-inoculating LAB mutant strains defective in lactate production with AABs, to assess both larval growth and continuous larval association with AABs. With respect to AAB-yeast interactions, metabolites released from yeast cells might benefit AAB growth, and this possibility will be investigated through the supplementation of AAB culture plates with candidate metabolites identified in the cell suspension supernatants of the late-stage yeasts.

Apart from these matters, the future directions or significance of this work could be discussed more in the manuscript.

We appreciate the reviewer's recommendations and will include additional descriptions regarding these aspects in the DISCUSSION section.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Weaknesses:

Despite describing important findings, I believe that a more thorough explanation of the experimental setup and the steps expected to occur in the exposed diet over time, starting with natural "inoculation" could help the reader, in particular the non-specialist, grasp the rationale and main findings of the manuscript. When exactly was the decision to collect early-stage samples made? Was it when embryos were detected in some of the samples? What are the implications of bacterial presence in the no-fly traps? These samples also harbored complex microbial communities, as revealed by sequencing. Were these samples colonized by microbes deposited with air currents? Were they the result of flies that touched the material but did not lay eggs? Could the traps have been visited by other insects? Another interesting observation that could be better discussed is the fact that adult flies showed a microbiome that more closely resembles that of the early-stage diet, whereas larvae have a more late-stage-like microbiome. It is easy to understand why the microbiome of the larvae would resemble that of the late-stage foods, but what about the adult microbiome? Authors should discuss or at least acknowledge the fact that there must be a microbiome shift once adults leave their food source. Lastly, the authors should provide more details about the metabolomics experiments. For instance, how were peaks assigned to leucine/isoleucine (as well as other compounds)? Were both retention times and MS2 spectra always used? Were standard curves produced? Were internal, deuterated controls used?

When exactly was the decision to collect early-stage samples made? Was it when embryos were detected in some of the samples?

We collected traps and early-stage samples 2.5 days after setting up the traps. This time frame was determined by pilot experiments. A shorter collection time resulted in a greater likelihood of obtaining no-fly traps, whereas a longer collection time caused larval overcrowding, as well as adults’ deaths from drowning in the liquid seeping out of fruits. These procedural details will be delineated in the MATERIALS AND METHODS section of the revised manuscript.

What are the implications of bacterial presence in the no-fly traps? These samples also harbored complex microbial communities, as revealed by sequencing. Were these samples colonized by microbes deposited with air currents? Were they the result of flies that touched the material but did not lay eggs? Could the traps have been visited by other insects?

We assume that the origins of the microbes detected in the no-fly trap foods vary depending on the species. For instance, Colletotrichum musae, the fungus that causes banana anthracnose, may have been present in fresh bananas before trap placement. The filamentous fungi could have originated from airborne spores, but they could also have been introduced by insects that feed on these fungi. We will include these possibilities in the DISCUSSION section of the revised manuscript.

Another interesting observation that could be better discussed is the fact that adult flies showed a microbiome that more closely resembles that of the early-stage diet, whereas larvae have a more late-stage-like microbiome. It is easy to understand why the microbiome of the larvae would resemble that of the late-stage foods, but what about the adult microbiome? Authors should discuss or at least acknowledge the fact that there must be a microbiome shift once adults leave their food source.

We are grateful for the reviewer's insightful suggestions regarding shifts in the adult microbiome. We plan to include in the DISCUSSION section of the revised manuscript the possibility that the microbial composition may change substantially during pupal stages and that microbes obtained after eclosion could potentially form the adult gut microbiota.

Lastly, the authors should provide more details about the metabolomics experiments. For instance, how were peaks assigned to leucine/isoleucine (as well as other compounds)? Were both retention times and MS2 spectra always used? Were standard curves produced? Were internal, deuterated controls used?

We appreciate the reviewer's advice. Detailed methods of the metabolomic experiments will be included in our revised manuscript.