Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorAmy AndreottiIowa State University, Ames, United States of America

- Senior EditorAmy AndreottiIowa State University, Ames, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

Bendzunas, Byrne et al. explore two highly topical areas of protein kinase regulation in this manuscript. Firstly, the idea that Cys modification could regulate kinase activity. The senior authors have published some standout papers exploring this idea of late, and the current work adds to the picture of how active site Cys might have been favoured in evolution to serve critical regulatory functions. Second, BRSK1/2 are understudied kinases listed as part of the "dark kinome" so any knowledge of their underlying regulation is of critical importance to advancing the field.

Strengths:

In this study, the author pinpoints highly-conserved, but BRSK-specific, Cys residues as key players in kinase regulation. There is a delicate balance between equating what happens in vitro with recombinant proteins relative to what the functional consequence of Cys mutation might be in cells or organisms, but the authors are very clear with the caveats relating to these connections in their descriptions and discussion. Accordingly, by extension, they present a very sound biochemical case for how Cys modification might influence kinase activity in cellular environs.

Comments on revised version:

The authors have satisfactorily addressed my concerns.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this study by Bendzunas et al, the authors show that the formation of intra-molecular disulfide bonds involving a pair of Cys residues near the catalytic HRD motif and a highly conserved T-Loop Cys with a BRSK-specific Cys at an unusual CPE motif at the end of the activation segment function as repressive regulatory mechanisms in BSK1 and 2. They observed that mutation of the CPE-Cys only, contrary to the double mutation of the pair, increases catalytic activity in vitro and drives phosphorylation of the BRSK substrate Tau in cells. Molecular modeling and molecular dynamics simulations indicate that oxidation of the CPE-Cys destabilizes a conserved salt bridge network critical for allosteric activation. The occurrence of spatially proximal Cys amino acids in diverse Ser/Thr protein kinase families suggests that disulfide-mediated control of catalytic activity may be a prevalent mechanism for regulation within the broader AMPK family. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying kinase regulation by redox-active Cys residues is fundamental as it appears to be widespread in signaling proteins and provides new opportunities to develop specific covalent compounds for the targeted modulation of protein kinases.

The authors demonstrate that intramolecular cysteine disulfide bonding between conserved cysteines can function as a repressing mechanism as indicated by the effect of DTT and the consequent increase in activity by BSK-1 and -2 (WT). The cause-effect relationship of why mutation of the CPE-Cys only increases catalytic activity in vitro and drives phosphorylation of the BRSK substrate Tau in cells is not clear to me. The explanation given by the authors based on molecular modeling and molecular dynamics simulations is that oxidation of the CPE-Cys (that will favor disulfide bonding) destabilizes a conserved salt bridge network critical for allosteric activation. However, no functional evidence of the impact of the salt-bridge network is provided. If you mutated the two main Cys-pairs (aE-CHRD and A-loop T+2-CPE) you lose the effect of DTT, as the disulfide pairs cannot be formed, hence no repression mechanisms take place, however when looking at individual residues I do not understand why mutating the CPE only results in the opposite effect unless it is independent of its connection with the T+2residue on the A-loop.

Strengths:

This is an important and interesting study providing new knowledge in the protein kinase field with important therapeutic implications for the rationale design and development of next-generation inhibitors.

Comments on revised version:

I have one remark related to question number 5 (my question was not clear enough). I meant if the authors did look at the functional relevance of the residues implicated in the identified salt-bridge network/tethers. What happens to the proteins functionally when you mutate those residues? (represented on Fig. 8).

Otherwise, the authors have satisfactorily addressed my concerns.

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

Bendzunas, Byrne et al. explore two highly topical areas of protein kinase regulation in this manuscript. Firstly, the idea that Cys modification could regulate kinase activity. The senior authors have published some standout papers exploring this idea of late, and the current work adds to the picture of how active site Cys might have been favoured in evolution to serve critical regulatory functions. Second, BRSK1/2 are understudied kinases listed as part of the "dark kinome" so any knowledge of their underlying regulation is of critical importance to advancing the field.

Strengths:

In this study, the author pinpoints highly-conserved, but BRSK-specific, Cys residues as key players in kinase regulation. There is a delicate balance between equating what happens in vitro with recombinant proteins relative to what the functional consequence of Cys mutation might be in cells or organisms, but the authors are very clear with the caveats relating to these connections in their descriptions and discussion. Accordingly, by extension, they present a very sound biochemical case for how Cys modification might influence kinase activity in cellular environs.

Weaknesses:

I have very few critiques for this study, and my major points are barely major.

Major points

(1) My sense is that the influence of Cys mutation on dimerization is going to be one of the first queries readers consider as they read the work. It would be, in my opinion, useful to bring forward the dimer section in the manuscript.

We agree that the influence of Cys on BRSK dimerization is a topic of significant interest. Our primary focus was to explore oxidative regulation of the understudied BRSK kinases as they contain a conserved T-loop Cys, and we have previously demonstrated that equivalent residues at this position in related kinases were critical drivers of oxidative modulation of catalytic activity. We have demonstrated here that BRSK1 & 2 are similarly regulated by redox and this is due to oxidative modification of the T+2 Cys, in addition to Cys residues that are conserved amongst related ARKs as well as BRSK-specific Cys. Although we also provide evidence for limited redox-sensitive higher order BRSK species (dimers) in our in vitro analysis, these represent a small population of the total BRSK protein pool (this was validated by SEC-MALs analysis). As such, we do not have strong evidence to suggest that these limited dimers significantly contribute to the pronounced inhibition of BRSK1 & 2 in the presence of oxidizing agents, and instead believe that other biochemical mechanisms likely drive this response. This may result from oxidized Cys altering the conformation of the activation loop. Indeed, the formation of an intramolecular disulfide within the T-loop of BRSK1 & 2, which we detected by MS, is one such regulatory modification. It is noteworthy, that intramolecular disulfide bonds within the T-loop of AKT and MELK have already been shown to induce an inactive state in the kinase, and we posit a similar mechanism for BRSKs.

While we recognize the potential importance of dimerization in this context, our current data from in vitro and cell-based assays do not provide substantial evidence to assert dimerization as a primary regulatory mechanism. Hence, we maintained a more conservative stance in our manuscript, discussing dimerization in later sections where it naturally followed from the initial findings. That being said, we acknowledge the potential significance of dimerization in the regulation of the BRSK T-loop cysteine. We believe this aspect merits further investigation and could indeed be the focus of a follow-up study.

(2) Relatedly, the effect of Cys mutation on the dimerization properties of preparations of recombinant protein is not very clear as it stands. Some SEC traces would be helpful; these could be included in the supplement.

In order to determine whether our recombinant BRSK proteins (and T-loop mutants) existed as monomers or dimers, we performed SDS-PAGE under reducing and non-reducing conditions (Fig 7). This unambiguously revealed that a monomer was the prominent species, with little evidence of dimers under these experimental conditions (even in the presence of oxidizing agents). Although we cannot discount a regulatory role for BRSK dimers in other physiological contexts, we could not produce sufficient evidence to suggest that multimerization played a substantial role in modifying BRSK kinase activity in our assays. We note that our in vitro analysis was performed using truncated forms of the protein, and as such it is entirely possible that regions of the protein that flank the kinase domain may serve additional regulatory functions that may include higher order BRSK conformations. In this regard, although we have not included SEC traces of our recombinant proteins, we have included analytical SEC-MALS of the truncated proteins (Supplementary Figure 6) which we believe to be more informative. We have also now included additional SEC-MALS data for BRSK2 C176A and C183A (Supplementary Figure 6d and e), which supports our findings in Fig 7, demonstrating the presence of limited dimer species under non-reducing conditions.

(3) Is there any knowledge of Cys mutants in disease for BRSK1/2?

We have conducted an extensive search across several databases: COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer), ProKinO (Protein Kinase Ontology), and TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas). These databases are well-regarded for their comprehensive and detailed records of mutations related to cancer and protein kinases. Our analysis using the COSMIC and TCGA databases focused on identifying any reported instances of Cys mutations in BRSK1/2 that are implicated in cancer. Additionally, we utilized the ProKinO database to explore the broader landscape of protein kinase mutations, including any potential disease associations of Cys mutations in BRSK1/2. However, we found no evidence to indicate the presence of Cys mutations in BRSK1/2 that are associated with cancer or disease. This lack of association in the current literature and database records suggests that, as of our latest search, Cys mutations in BRSK1/2 have not been reported as significant contributors to pathogenesis.

(4) In bar charts, I'd recommend plotting data points. Plus, it is crucial to report in the legend what error measure is shown, the number of replicates, and the statistical method used in any tests.

We have added the data points to the bar charts and included statistical methods in figure legends.

(5) In Figure 5b, the GAPDH loading control doesn't look quite right.

The blot has been repeated and updated.

(6) In Figure 7 there is no indication of what mode of detection was used for these gels.

We have updated the figure legend to confirm that the detection method was western blot.

(7) Recombinant proteins - more detail should be included on how they were prepared. Was there a reducing agent present during purification? Where did they elute off SEC... consistent with a monomer of higher order species?

We have added ‘produced in the absence of reducing agents unless stated otherwise’ in the methods section to improve clarity. Although we have not added additional sentences to describe the elution profile of the BRSK proteins by SEC during purification, we believe that the inclusion of analytical SEC-MALS data is sufficient evidence that the proteins are largely monomeric under non-reducing conditions.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this study by Bendzunas et al, the authors show that the formation of intra-molecular disulfide bonds involving a pair of Cys residues near the catalytic HRD motif and a highly conserved T-Loop Cys with a BRSK-specific Cys at an unusual CPE motif at the end of the activation segment function as repressive regulatory mechanisms in BSK1 and 2. They observed that mutation of the CPE-Cys only, contrary to the double mutation of the pair, increases catalytic activity in vitro and drives phosphorylation of the BRSK substrate Tau in cells. Molecular modeling and molecular dynamics simulations indicate that oxidation of the CPE-Cys destabilizes a conserved salt bridge network critical for allosteric activation. The occurrence of spatially proximal Cys amino acids in diverse Ser/Thr protein kinase families suggests that disulfide-mediated control of catalytic activity may be a prevalent mechanism for regulation within the broader AMPK family. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying kinase regulation by redox-active Cys residues is fundamental as it appears to be widespread in signaling proteins and provides new opportunities to develop specific covalent compounds for the targeted modulation of protein kinases.

The authors demonstrate that intramolecular cysteine disulfide bonding between conserved cysteines can function as a repressing mechanism as indicated by the effect of DTT and the consequent increase in activity by BSK-1 and -2 (WT). The cause-effect relationship of why mutation of the CPE-Cys only increases catalytic activity in vitro and drives phosphorylation of the BRSK substrate Tau in cells is not clear to me. The explanation given by the authors based on molecular modeling and molecular dynamics simulations is that oxidation of the CPE-Cys (that will favor disulfide bonding) destabilizes a conserved salt bridge network critical for allosteric activation. However, no functional evidence of the impact of the salt-bridge network is provided. If you mutated the two main Cys-pairs (aE-CHRD and A-loop T+2-CPE) you lose the effect of DTT, as the disulfide pairs cannot be formed, hence no repression mechanisms take place, however when looking at individual residues I do not understand why mutating the CPE only results in the opposite effect unless it is independent of its connection with the T+2residue on the A-loop.

Strengths:

This is an important and interesting study providing new knowledge in the protein kinase field with important therapeutic implications for the rationale design and development of next-generation inhibitors.

Weaknesses:

There are several issues with the figures that this reviewer considers should be addressed.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for The Authors):

Major points

Page 26 - the discussion could be more concise. There's an element of recapping the results, which should be avoided.

Regarding the conciseness of the discussion section, we have thoroughly revised it to ensure a more succinct presentation, deliberately avoiding the recapitulation of results. The revised discussion now focuses on interpreting the findings and their implications, steering clear of redundancy with the results section.

Figure 1b seems to be mislabeled/annotated. I recommend checking whether the figure legends match more broadly. Figure 1 appears to be incorrectly cited throughout the results.

Thank you for pointing out the discrepancies in the labeling and citation of Figure 1b. We have carefully reviewed and corrected these issues to ensure that all figure labels, legends, and citations accurately reflect the corresponding data and illustrations. We appreciate your attention to detail and the opportunity to improve the clarity and accuracy of our presentation.

Figure 6 - please include a color-coding key in the figure. Further support for these simulations could be provided by supplementary movies or plots of the interaction. Figure 4 colour palette should be adjusted for the spheres in the Richardson diagrams to have greater distinction.

As suggested, we have amended the colour palette in Figure 4 to improve conformity throughout the figure.

Minor points

Figure 2 - it'd be helpful to know what the percentage coverage of peptides is.

We have updated the figure legend to include peptide coverage for both proteins

Some typos - Supp 2 legend "Domians".

Fixed

Figure 6 legend - analyzed by needs a space;

Fixed

Fig 8 legend schematic misspelled.

Fixed

Broadly, if you Google T-loop you get a pot pourri of enzyme answers. Why not just use Activation loop?

The choice of "T-loop" over "Activation loop" in our manuscript was made to maintain consistency with other literature in the field, and in particular our previous paper “Aurora A regulation by reversible cysteine oxidation reveals evolutionarily conserved redox control of Ser/Thr protein kinase activity” where we refer to the activation loop cysteine as T-loop + 2. We acknowledge the varied enzyme contexts in which "T-loop" is used and agree on the importance of clarity. To address this, we made an explicit note in the manuscript that the "T-loop" is also referred to as the "Activation loop", ensuring readers are aware of the interchangeable use of these terms. Additionally, this nomenclature facilitates a more straightforward designation of cysteine residues within the loop (T+2 Cysteine). We believe this approach balances adherence to established conventions with the need for clarity and precision in our descriptions.

Methods - what is LR cloning. Requires some definition. Some manufacturer detail is missing in methods, and referring to prior work is not sufficient to empower readers to replicate.

We agree, and have added the following to the methods section:

“BRSK1 and 2 were sub-cloned into pDest vectors (to encode the expression of N-terminal Flag or HA tagged proteins) using the Gateway LR Clonase II system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. pENtR BRSK1/2 clones were obtained in the form of Gateway-compatible donor vectors from Dr Ben Major (Washington University in St. Louis). The Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix mediates recombination between the attL sites on the Entry clone and the attR sites on the destination vector. All cloned BRSK1/2 genes were fully sequenced prior to use.”

Page 7 - optimal settings should be reported. How were pTau signals quantified and normalised?

We have added the following to the methods section:

“Two-color Western blot detection method employing infrared fluorescence was used to measure the ratio of Tau phospho serine 262 to total Tau. Total GFP Tau was detected using a mouse anti GFP antibody and visualized at 680 nm using goat anti mouse IRdye 680 while phospho-tau was detected using a Tau phospho serine 262 specific antibody and visualized at 800 nm using goat anti rabbit IRdye 800. Imaging was performed using a Licor Odessey Clx with scan control settings set to 169 μm, medium quality, and 0.0 mm distance. Quantification was performed using Licor image studio on the raw image files. Total Tau to phospho Tau ratio was determined by measuring the ratio of the fluorescence intensities measured at 800 nm (pTau) to those at 680 nm (total tau).”

In the Figure 6g-j legend, the salt bridge is incorrectly annotated as E185-R248 rather than 258.

Fixed

Lines 393-395 provides a repeat statement on BRSKs phosphorylating Tau (from 388-389).

We have removed the repetition and reworded the opening lines of the results section to improve the overall flow of the manuscript.

Supp. Figure 1 is difficult to view - would it be possible to increase the size of the phylogenetic analysis?

We thank the reviewer for this observation. We have rotated (90°) and expanded the figure so that it can be more clearly viewed

Supp. Figure 2 - BRSK1/2 incorrectly spelled.

Fixed

Please check the alignment of labels in Supp. Figure 3e.

Fixed

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

(1) In Figure 1, current panel b is not mentioned/described in the figure legend and as a consequence, the rest of the panels in the legends do not fit the content of the figure.

Reviewer 1 also noted this error, and we have amended the manuscript accordingly.

What is the rationale for using the HEK293T cells as the main experimental/cellular system? Are there cell lines that express both proteins endogenously so that the authors can recapitulate the results obtained from ectopic overexpression?

The selection of HEK-293T cells was driven by their well-established utility in overexpression studies, which make them ideal for the investigation of protein interactions and redox regulation. This cell line's robust transfection efficiency and well-characterized biology provide a reliable platform for dissecting the molecular mechanisms underlying the redox regulation of proteins. Furthermore, the use of HEK-293T cells aligns with the broader scientific practice, serving as a common ground for comparability with existing literature in the field of BRSK1/2 signaling, protein regulation and interaction studies.

The application of HEK-293T cells as a model system in our study serves as a foundational step towards eventually elucidating the functions of BRSK1/2 in neuronal cells, where these kinases are predominantly expressed and play critical roles. Given the fact that BRSKs are classed as ‘understudied’ kinases, the choice of a HEK-293T co-overexpression system allowed us to analyze the direct effects of BRSK kinase activity (using phosphorylation of Tau as a readout) in a cellular context and in more controlled manner. This approach not only aids in the establishment of a baseline understanding of the redox regulation of BRSK1/2, but also sets the stage for subsequent investigations in more physiologically relevant neuronal models

In current panel d, could the authors recapitulate the same experimental conditions as in current panel c?

Figure 1 panel c shows that both BRSK1 and 2 are reversibly inhibited by oxidizing agents such as H2O2, whilst panels d and e show the concentration dependent activation and inhibition of the BRSKs with increasing concentrations of DTT and H2O2 respectively. The experimental conditions were identical, other than changing amounts of reducing and oxidizing agents, and used the same peptide coupled assays. Data for all experiments were originally collected in ‘real time’ as depicted in Fig 1c (increase in substrate phosphorylation over time). However, to aid interpretation of the data, we elected to present the latter two panels as dose response curves by calculating the change in the rate of enzyme activity (shown as pmol phosphate incorporated into the peptide substrate per min) for each condition. To aid the reader, we now include an additional supplementary figure (new supplementary figure 2) depicting BRSK1 and 2 dependent phosphorylation of the peptide substrate in the presence of different concentrations of DTT and H2O2 in a real time (kinetic) assay. The new data shown is a subset of the unprocessed data that was used to calculate the rates of BRSK activity in Fig 1d & e.

Why did the authors use full-length constructs in these experiments and did not in e.g. Figure 2 where they used KD constructs instead?

In the initial experiments, illustrated in Figure 1, we employed full-length protein constructs to establish a proof of concept, demonstrating the overall behavior and interactions of the proteins in their full-length form. This confirmed that BRSK1 & 2, which both contain a conserved T + 2 Cys residue that is frequently prognostic for redox sensitivity in related kinases, displayed a near-obligate requirement for reducing agents to promote kinase activity.

Subsequently, in Figure 2, our focus shifted towards delineating the specific regions within the proteins that are critical for redox regulation. By using constructs that encompass only the kinase domain, we aimed to demonstrate that the redox-sensitive regulation of these proteins is predominantly mediated by specific cysteine residues located within the kinase domain itself. This strategic use of the kinase domain of the protein allowed for a more targeted investigation. Furthermore, in our hands these truncated forms of the protein were more stable at higher concentrations, enabling more detailed characterization of the proteins by DSF and SEC-MALS. We predict that the flanking disordered regions of the full-length protein (as predicted by AlphaFold) contribute to this effect.

(2) In Figure 2, Did the authors try to do LC/MS-MS in the same experimental conditions as in Figure 1 (e.g. buffer minus/plus DTT, H2O2, H2O2 + DTT)?

We would like to clarify that the mass spectrometry experiments were conducted exclusively on proteins purified under native (non-reducing) conditions. We did not extend the LC/MS-MS analyses to include proteins treated with various buffer conditions such as minus/plus DTT, H2O2, or H2O2 + DTT as used in the experiments depicted in Figure 1. Given that we could readily detect disulfides in the absence of oxidizing agents, we did not see the benefit of additional treatment conditions as peroxide treatment of protein samples can frequently complicate interpretation of MS data. However, it should be noted that prior to MS analysis, tryptic peptides were subjected to a 50:50 split, with one half alkylated in the presence of DTT (as described in the methods section) to eliminate disulfides and other transiently oxidized Cys forms. Comparative analysis between reduced and non-reduced tryptic peptides improved our confidence when assigning disulfide bonds (which were eliminated in identical peptides in the presence of DTT).

On panel b, why did the authors show alphafold predictions and not empiric structural information (e.g. X-ray, EM,..)?

The AlphaFold models were primarily utilized to map the general locations of redox-sensitive cysteine pairs within the proteins of interest. Although we have access to the crystal structure of mouse BRSK2, they do not fully capture the active conformation seen in the Alphafold model of the human version. The use of AlphaFold models for human proteins in this study aids in consistently tracking residue numbering across the manuscript, offering a useful framework for understanding the spatial arrangement of these critical cysteine pairs in their potentially active-like states. This approach facilitates our analysis and discussion by providing a reference for the structural context of these residues in the human proteins.

What was the rationale for using the KD construct and not the FL as in Figure 1?

The rationale to use the kinase domain was primarily based on the significantly lower confidence in the structural predictions for regions outside the kinase domain (KD). Our experimental focus was to investigate the role of conserved cysteine residues within the kinase domain, which are critical for the protein's function and regulation. This targeted approach allowed us to concentrate our analyses on the most functionally relevant and structurally defined portion of the protein, thereby enhancing the precision and relevance of our findings. As is frequently the case, truncated forms of the protein, consisting only of the kinase domain, are much more stable than their full length counterparts and are therefore more amenable to in vitro biochemical analysis. In our hands this was true for both BRSK1 and 2, and as such much of the data collected here was generated using kinase-domain (KD) constructs. Simulations using the KD structures are therefore much more representative of our original experimental setup.

The BSK1 KD construct appears to be rather inactive and not responsive to DTT treatment. Could the authors comment on the differences observed with the FL construct of Figure 1

It is important to note that BRSK1, in general, exhibits lower intrinsic activity compared to BRSK2. This reduced activity could be attributed to a range of factors, including the need for activation by upstream kinases such as LKB1, as well as potential post-translational modifications (PTMs) that may be absent in the bacterially expressed KD construct. The full-length forms of the protein were purified from Sf21 cells, and as such may have additional modifications that are lacking in the bacterially derived KD counterparts. We also cannot discount additional regulatory roles of the regions that flank the KD, and these may contribute in part to the modest discrepancy observed between constructs. Despite these differences, it is crucial to emphasize that both the KD and FL constructs of BRSK1 are regulated by DTT, indicating a conserved redox-dependent activation for both of the related BRSK proteins.

(3) In Figure 4, on panel A wouldn´t the authors expect that mutating on the pairs e.g. C198A in BSK1 would have the same effect as mutating the C191 from the T+2 site? Did they try mutating individual sites of the aE/CHRD pair? The same will apply to BSK2

We appreciate the insightful comment. It's important to clarify that the redox regulation of these proteins is influenced not solely by the formation of disulfide bonds but also by the oxidation state of individual cysteine residues, particularly the T+2 Cys. This nuanced mechanism of regulation allows for a diverse range of functional outcomes based on the specific cysteine involved and its state of oxidation. This aspect forms a key finding of our paper, highlighting the complexity of redox regulation beyond mere disulfide bond formation. For example, AURA kinase activity is regulated by oxidation of a single T+2 Cys (Cys290, equivalent to Cys191 and Cys176 of BRSK1 and 2 respectively), but this regulation can be supplemented through artificial incorporation of a secondary Cys at the DFG+2 position (Byrne et al., 2020). This targeted genetic modification or AURA mirrors equivalent regulatory disulfide-forming Cys pairs that naturally occur in kinases such as AKT and MELK, and which provide an extra layer of regulatory fine tuning (and a possible protective role to prevent deleterious over oxidation) to the T+2 Cys. We surmise that the CPE Cys is also an accessory regulatory element to the T+2 Cys in BRSK1 +2, which is the dominant driver of BRSK redox sensitivity (as judged by the fact that CPE Cys mutants are still potently regulated by redox [Fig 4]), by locking it in an inactive disulfide configuration.

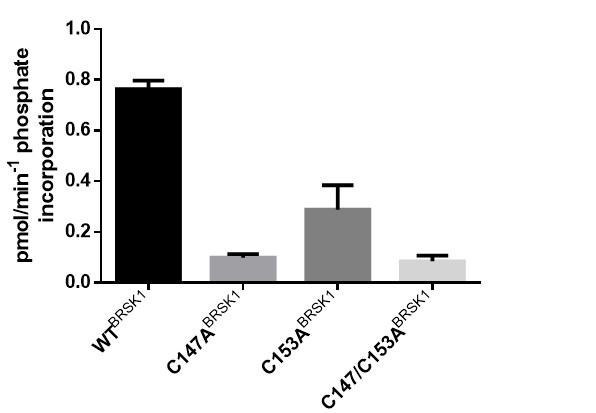

In our preliminary analysis of BRSK1, we observed that mutations of individual sites within the aE/CHRD pair was similarly detrimental to kinase activity as a tandem mutation (see reviewer figure 1). As discussed in the manuscript, we think that these Cys may serve important structural regulatory functions and opted to focus on co-mutations of the aE/CHRD pair for the remainder of our investigation.

Author response image 1.

In vitro kinase assays showing rates of in vitro peptide phosphorylation by WT and Cys-to-Ala (aE/CHRD residues) variants of BRSK1 after activation by LKB1.

In panels C and D, the same experimental conditions should have been measured as in A and B.

Panels A and B were designed to demonstrate the enzymatic activity and the response to DTT treatment to establish the baseline redox regulation of the kinase and a panel of Cys-to-Ala mutant variants. In contrast, panels C and D were specifically focused on rescue experiments with mutants that showed a significant effect under the conditions tested in A and B. These panels were intended to further explore the role of redox regulation in modulating the activity of these mutants, particularly those that retained some level of activity or exhibited a notable response to redox changes.

The rationale for this experimental design was to prioritize the investigation of mutants, such as those at the T+2 and CPE cysteine sites, which provided the most insight into the redox-dependent modulation of kinase activity. Other mutants, which resulted in inactivation, were deprioritized in this context as they offered limited additional information regarding the redox regulation mechanism. This focused approach allowed us to delve deeper into understanding how specific cysteine residues contribute to the redox-sensitive control of kinase function, aligning with the overall objective of elucidating the nuanced roles of redox regulation in kinase activity.

(4) In figure 5: Why did the authors use reduced Glutathione instead of DTT? The authors should have recapitulated the same experimental conditions as in Figure 4 and not focused only on the T+2 or the CPE single mutants but using the double and the aE/CHRD mutants as well, as internal controls and validation of the enzymatic assays using the modified peptide

Regarding the use of reduced glutathione (GSH) instead of DTT in Figure 5, we chose GSH for its well characterized biological relevance as an antioxidant in cellular responses to oxidative stress. Furthermore, while DTT has been widely used in experimental setups, it is also potentially cytotoxic at high concentrations.

Addressing the point on experimental consistency with Figure 4, we appreciate the suggestion and indeed had already conducted such experiments (Previously Supp Fig 3, now changed to current Supp Fig 4). These experiments include analyses of BRSK mutant activity in a HEK-293T model. However, we chose not to focus on inactivating mutants (such as the aE/CHRD mutants which had depleted expression levels possibly as a consequence of compromised structural integrity) or pursue the generation of double mutant CMV plasmids, as these were deemed unlikely to add significant insights into the core narrative of our study. Our focus remained on the mutants that yielded the most informative results regarding the redox regulation mechanisms in the in vitro setting, ensuring a clear and impactful presentation of our findings.

A time course evaluation of the reducing or oxidizing reagents should have been performed. Would we expect that in WT samples, and in the presence of GSH, and also in the case of the CPE mutant, an increment in the levels of Tau phosphorylation as a readout of BSK1-2 activity?

We acknowledge the importance of such analyses in understanding the dynamic nature of redox regulation on kinase activity and have included a time course (Supp Fig 2 e-g). These results confirm a depletion of Tau phosphorylation over time in response to peroxide generated by the enzyme glucose oxidase.

(5) In Figure 6, did the authors look at the functional impact of the residues with which interact the T+2 and the CPE motifs e.g. T174 and the E185-R258 tether?

Our primary focus was on the salt bridges, as this is a key regulatory structural feature that is conserved across many kinases. Regarding the additional interactions mentioned, we have thoroughly evaluated their roles and dynamics through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations but did not find any results of significant relevance to warrant inclusion.

(6) In Figure 7: Did the author look at the oligomerization state of the BSK1-2 multimers under non-reducing conditions? Were they also observed in the case of the FL constructs? What was the stoichiometry?

Our current work indicates that the kinase domain of BRSK1-2 primarily exists in a monomeric state, with some evidence of dimerization or multimer formation under specific conditions. Our SEC-MALS (Supp Fig 6) and SDS-PAGE analysis (Figure 7) clearly demonstrates that monomers are overwhelmingly the dominant species under non-reducing conditions (>90 %). We also conclude that these limited oligomeric species can be removed by inclusion of reducing agents such as DTT (Figure 7), which may suggest a role for a Cys residue(s). Notably, removal of the T+2 Cys was insufficient to prevent multimerization.

We were unable to obtain reliable SEC-MALS data for the full-length forms of the protein, likely due to the presence of disordered regions that flank the kinase domain which results in a highly heterodispersed and unstable preparation (at the concentrations required for SEC-MALS). Although we are therefore unable to comment on the stoichiometry of FL BRSK dimers, we can detect BRSK1 and 2 hetero- and homo-complexes in HEK-293T cells by IP, which supports the existence of limited BRSK1 & 2 dimers (Supp Fig 6a). However, we were unable to detect intermolecular disulfide bonds by MS, although this does not necessarily preclude their existence. The physiological role of BRSK multimerization (if any) and establishing specifically which Cys residues drive this phenomenon is of significant interest to our future investigations.