Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

In their manuscript, Yu et al. describe the chemotactic gradient formation for CCL5 bound to - i.e. released from - glycosaminoglycans. The authors provide evidence for phase separation as the driving mechanism behind chemotactic gradient formation. A conclusion towards a general principle behind the finding cannot be drawn since the work focuses on one chemokine only, which is particularly prone to glycan-induced oligomerisation.

Strengths:

The principle of phase separation as a driving force behind and thus as an analytical tool for investigating protein interactions with strongly charged biomolecules was originally introduced for protein-nucleic acid interactions. Yu et al. have applied this in their work for the first time for chemokine-heparan sulfate interactions. This opens a novel way to investigate chemokine-glycosaminoglycan interactions in general.

Response: Thanks for the encouragement of the reviewer.

Weaknesses:

As mentioned above, one of the weaknesses of the current work is the exemplification of the phase separation principle by applying it only to CCL5-heparan sulfate interactions. CCL5 is known to form higher oligomers/aggregates in the presence of glycosaminoglycans, much more than other chemokines. It would therefore have been very interesting to see, if similar results in vitro, in situ, and in vivo could have been obtained by other chemokines of the same class (e.g. CCL2) or another class (like CXCL8).

Response: We share the reviewer’s opinion that to investigate more molecules/cytokines that interact with heparan sulfate in the system should be of interesting. We expect that researchers in the field will adapt the concept to continue the studies on additional molecules. Nevertheless, our earlier study has demonstrated that bFGF was enriched to its receptor and triggered signaling transduction through phase separation with heparan sulfate (PMID: 35236856; doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28765-z), which supports the concept that phase separation with heparan sulfate on the cell surface may be a common mechanism for heparan sulfate binding proteins. The comment of the reviewer that phase separation is related to oligomerization is demonstrated in (Figure 1—figure supplement 2C and D), showing that the more easily aggregated mutant, A22K-CCL5, does not undergo phase separation.

In addition, the authors have used variously labelled CCL5 (like with the organic dye Cy3 or with EGFP) for various reasons (detection and immobilisation). In the view of this reviewer, it would have been necessary to show that all the labelled chemokines yield identical/similar molecular characteristics as the unlabelled wildtype chemokine (such as heparan sulfate binding and chemotaxis). It is well known that labelling proteins either by chemical tags or by fusion to GFPs can lead to manifestly different molecular and functional characteristics.

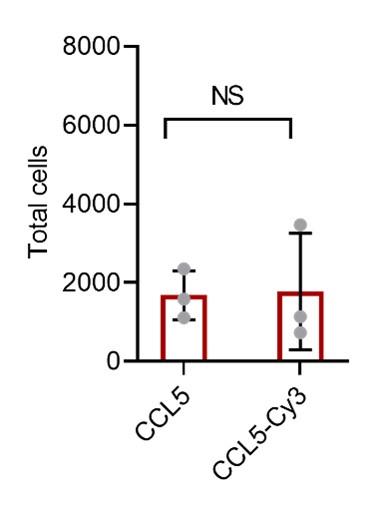

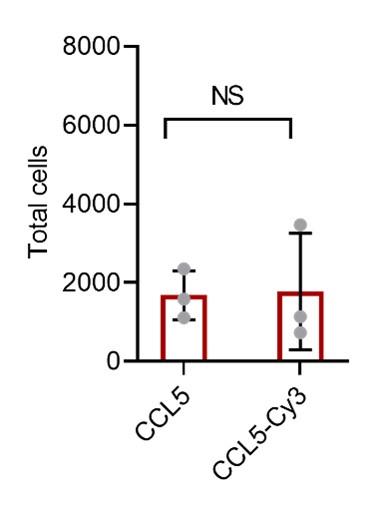

Response: We agree with the reviewer that labeling may lead to altered property of a protein, thus, we have compared chemotactic activity of CCL5 and CCL5-EGFP (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). To further verify this, we performed additional experiment to compare chemotactic activity between CCL5 and Cy3-CCL5 (see Author response image 1). For the convenience of readers, we have combined the original Figure 2—figure supplement 1 with the new data (Figure R1), which replaced original Figure 2—figure supplement 1.

Author response image 1.

Chemotactic function of CCL5-EGFP and CCL5-Cy3. Cy3-Labeled CCL5 has similar activity as CCL5, 50 nM CCL5 or CCL5-Cy3 were added to the lower chamber of the Transwell. THP-1 cells were added to upper chambers. Data are mean ± s.d. n=3. P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. NS, Not Significant.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Although the study by Xiaolin Yu et al is largely limited to in vitro data, the results of this study convincingly improve our current understanding of leukocyte migration.

(1) The conclusions of the paper are mostly supported by the data although some clarification is warranted concerning the exact CCL5 forms (without or with a fluorescent label or His-tag) and amounts/concentrations that were used in the individual experiments. This is important since it is known that modification of CCL5 at the N-terminus affects the interactions of CCL5 with the GPCRs CCR1, CCR3, and CCR5 and random labeling using monosuccinimidyl esters (as done by the authors with Cy-3) is targeting lysines. Since lysines are important for the GAG-binding properties of CCL5, knowledge of the number and location of the Cy-3 labels on CCL5 is important information for the interpretation of the experimental results with the fluorescently labeled CCL5. Was the His-tag attached to the N- or C-terminus of CCL5? Indicate this for each individual experiment and consider/discuss also potential effects of the modifications on CCL5 in the results and discussion sections.

Response: We agree with the reviewer that labeling may lead to altered property of a protein, thus, we have compared chemotactic activity of CCL5 and CCL5-EGFP (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). To further verify this, we performed additional experiment to compare chemotactic activity between CCL5 and Cy3-CCL5 (see Author response image 1). For the convenience of readers, we have combined the original Figure 2—figure supplement 1 with the new data (Author response image 1), which replaced original Figure 2—figure supplement 1.

The His-tag is attached to the C-terminus of CCL5, in consideration of the potential impact on the N-terminus.

(2) In general, the authors appear to use high concentrations of CCL5 in their experiments. The reason for this is not clear. Is it because of the effects of the labels on the activity of the protein? In most biological tests (e.g. chemotaxis assays), unmodified CCL5 is active already at low nM concentrations.

Response: We agree with the reviewer that the CCL5 concentrations used in our experiments were higher than reported chemotaxis assays and also higher than physiological levels in normal human plasma. In fact, we have performed experiments with lower concentration of CCL5, where the effect of LLPS was not seen though the chemotactic activity of the cytokine was detected. Thus, LLPS-associated chemotactic activity may represent a scenario of acute inflammatory condition when the inflammatory cytokines can increase significantly.

(3) For the statistical analyses of the results, the authors use t-tests. Was it confirmed that data follow a normal distribution prior to using the t-test? If not a non-parametric test should be used and it may affect the conclusions of some experiments.

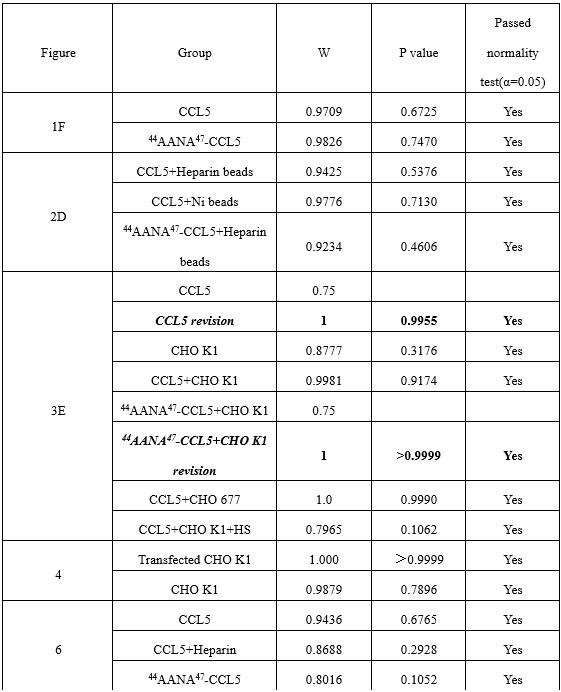

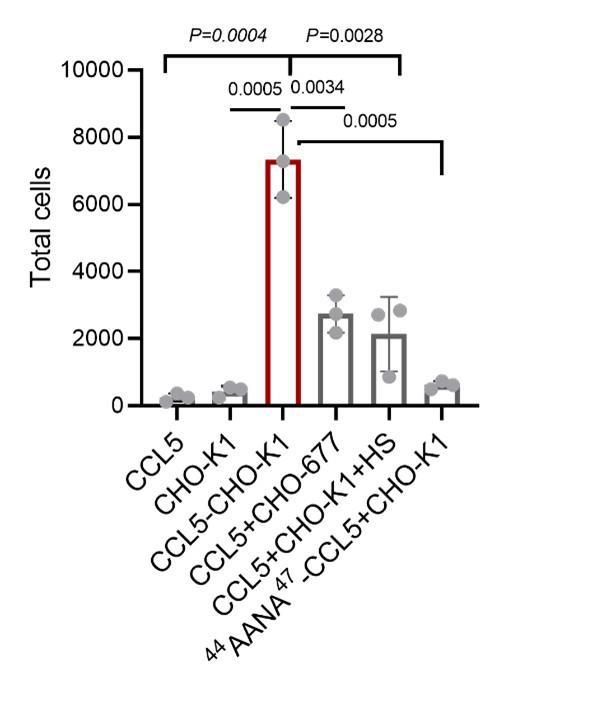

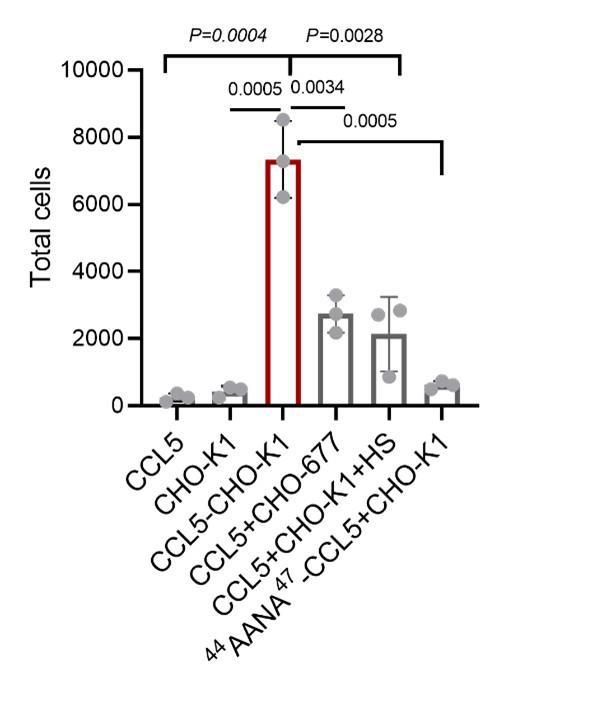

Response: We thank the reviewer for pointing out this issue. As shown in Author response table 1, The Shapiro-Wilk normality test showed that only two control groups (CCL5 and 44AANA47-CCL5+CHO K1) in Figure 3 did not conform to the normal distribution. The error was caused by using microculture to count and calculate when there were very few cells in the microculture. For these two groups, we re-counted 100 μL culture medium to calculate the number of cells. The results were consistent with the positive distribution and significantly different from the experimental group (Author response image 3). The original data for the number of cells chemoattractant by 500 nM CCL5 was revised from 0, 247, 247 to 247, 123, 370 and 500 nM 44AANA47 +CHO-K1 was revised from 1111, 1111, 98 to 740, 494, 617. The revised data does not affect the conclusion.

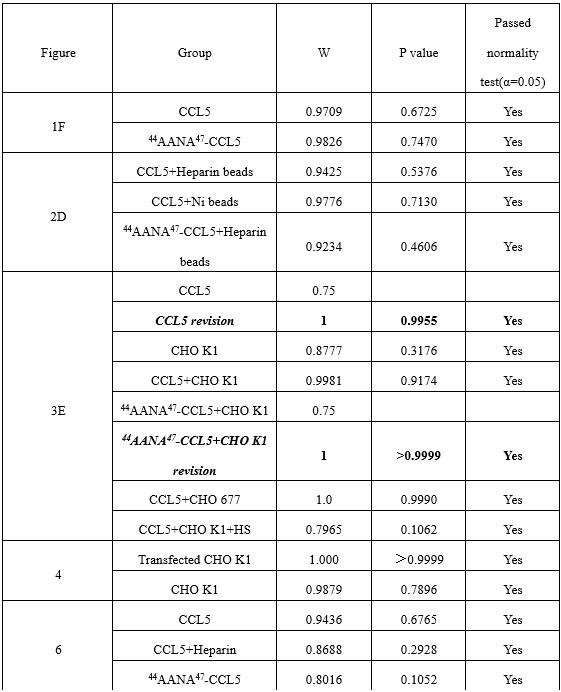

Author response table 1.

Table R1 Shapiro-Wilk test results of statistical data in the manuscript

Author response image 3.

Quantification of THP-1collected from the lower chamber. Data are mean ± s.d. n=3. P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed t-tests.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1:

See the weaknesses section of the Public Review. In addition, the authors should discuss the X-ray structure of CCL5 in complex with a heparin disaccharide in comparison with their docked structure of CCL5 and a heparin tetrasaccharide.

Response: Our study, in fact, is strongly influenced by the report (Shaw, Johnson et al., 2004) that heparin disaccharide interaction with CCL5, which is highlighted in the text (page5, line100-102).

Reviewer #2:

(1) Clearly indicate in the results section and figure legends (also for the supplementary figures) which form and concentration of CCL5 is used.

Response: The relevant missing information is indicated across the manuscript.

(2) Clearly indicate which GAG was used. Was it heparin or heparan sulfate and what was the length (e.g. average molecular mass if known) or source (company?)?

Response: Relevant information is added in the section “Materials and Methods.

(3) Line 181: What do you mean exactly with "tiny amounts"?

Response: “tiny amounts” means 400 transfected cells. This is described in the section of Materials and Methods. It is now also indicated in the text and legend to the figure.

(4) Lines 216-217: This is a very general statement without a link to the presented data. No combination of chemokines is used, in vivo testing is limited (and I agree very difficult). You may consider deleting this sentence (certainly as an opening sentence for the Discussion).

Response: We appreciate very much for the thoughtful suggestion of the reviewer. This sentence is deleted in the revised manuscript.

(5) Why was 5h used for the in vitro chemotaxis assay? This is extremely long for an assay with THP-1 cells.

Response: We apologize for the unclear description. The 5 hr includes 1 hr pre- incubation of CCL5 with the cells enable to form phase separation. After transferring the cells into the upper chamber, the actual chemotactic assay was 4 hr. This is clarified in the Materials and Methods section and the legend to each figure.

(6) Define "Sec" in Sec-CCL5-EGFP and "Dil" in the legend of Figure 4.

Response: The Sec-CCL5-EGFP should be “CCL5-EGFP’’, which has now been corrected. Dil is a cell membrane red fluorescent probe, which is now defined.

(7) Why are different cell concentrations used in the experiment described in Figure 5?

Response: The samples were from three volunteers who exhibited substantially different concentrations of cells in the blood. The experiment was designed using same amount of blood, so we did not normalize the number of the cell used for the experiment. Regardless of the difference in cell numbers, all three samples showed the same trend.

(8) Check the text for some typos: examples are on line 83 "ratio of CCL5"; line 142 "established cell lines"; line 196 "peripheral blood mononuclear cells"; line 224 "to mediate"; line 226 "bind"; line 247 "to form a gradient"; line 248 "of the glycocalyx"; line 343 and 346 "tetrasaccharide"; line 409-410 "wild-type"; line 543 "on the surface of CHO-K1 and CHO-677"; line 568 "white".

Response: Thanks for the careful reading. The typo errors are corrected and Manuscript was carefully read by colleagues.