Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorJennifer GrohDuke University, Durham, United States of America

- Senior EditorJoshua GoldUniversity of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Most studies in sensory neuroscience investigate how individual sensory stimuli are represented in the brain (e.g., the motion or color of a single object). This study starts tackling the more difficult question of how the brain represents multiple stimuli simultaneously and how these representations help to segregate objects from cluttered scenes with overlapping objects.

Strengths:

The authors first document the ability of humans to segregate two motion patterns based on differences in speed. Then they show that a monkey's performance is largely similar; thus establishing the monkey as a good model to study the underlying neural representations.

Careful quantification of the neural responses in the middle temporal area during the simultaneous presentation of fast and slow speeds leads to the surprising finding that, at low average speeds, many neurons respond as if the slowest speed is not present, while they show averaged responses at high speeds. This unexpected complexity of the integration of multiple stimuli is key to the model developed in this paper.

One experiment in which attention is drawn away from the receptive field supports the claim that this is not due to the involuntary capture of attention by fast speeds.

A classifier using the neuronal response and trained to distinguish single speed from bi-speed stimuli shows a similar overall performance and dependence on the mean speed as the monkey. This supports the claim that these neurons may indeed underlie the animal's decision process.

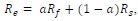

The authors expand the well-established divisive normalization model to capture the responses to bi-speed stimuli. The incremental modeling (eq 9 and 10) clarifies which aspects of the tuning curves are captured by the parameters.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This study concerns how macaque visual cortical area MT represents stimuli composed of more than one speed of motion.

Strengths:

The study is valuable because little is known about how the visual pathway segments and preserves information about multiple stimuli. The study presents compelling evidence that (on average) MT neurons shift from faster-speed-takes-all at low speeds to representing the average of the two speeds at higher speeds. An additional strength of the study is the inclusion of perceptual reports from both humans and one monkey participant performing a task in which they judged whether the stimuli involved one vs two different speeds. Ultimately, this study raises intriguing questions about how exactly the response patterns in visual cortical area MT might preserve information about each speed, since such information is potentially lost in an average response as described here.

Reviewing Editor comment on revised version:

The remaining concern was resolved.