Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife assessment

This important study investigates the transcriptional changes in neurons that underlie loss of learning and memory with age in C. elegans, and how cognition is maintained in insulin/IGF-1-like signaling mutants. The presented evidence is convincing, utilizing a cutting-edge method to isolate neurons from worms for genomics that is clearly conveyed with a rigorous experimental approach. Overall, this study supports that older daf-2 worms maintain cognitive function via mechanisms that are unique from younger wild type worms, which will be of interest to neuroscientists and researchers studying ageing.

Thank you, we appreciate the positive comments.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors perform RNA-seq on FACS-isolated neurons from adult worms at days 1 and 8 of adulthood to profile the gene expression changes that occur with cognitive decline. Supporting data are included indicating that by day 7 of adulthood, learning and memory are reduced, indicating that this time point or after represents cognitively aged worms. Neuronal identity genes are reduced in expression within cognitively aged worms, whereas genes involved in proteostasis, transcription/chromatin, and stress response are elevated. A number of specific examples are provided, representing markers of specific neuronal subtypes, and correlating expression changes to the erosion of particular functions (e.g. motor neurons, chemosensory neurons, aversive learning neurons, etc).

To investigate whether the upregulation of genes in neurons with age is compensatory or deleterious, the authors reduced the expression of a set of three significantly upregulated genes and performed behavioral assays in young adults. In each case, reduction of expression improved memory, consistent with a model in which age-associated increases impair neuronal function. This claim would be bolstered by an experiment elevating the expression of these genes in young neurons, which should reduce the learning index if the hypothesis is correct.

This is an interesting suggestion. Our long-term goal is to find ways to improve memory, and to better understand the “rules” that might govern changes with age. In this case, were interested in addressing the hypothesis that genes that rise with age must be compensatory, which is a frequently stated theory that is not often tested. Here we showed that knocking down three genes that are upregulated in aged animals improved memory; our results suggest that the wild-type functions of these genes are likely deleterious for learning and memory functions, and further, that their increased expression with age is not a compensatory function. Certainly for future work, it might be interesting to better understand how and why these specific genes have a deleterious function that increases with age, and whether that function is different in younger animals where they are not highly expressed.

The authors then characterize learning and memory in wild-type, daf-2, and daf-2/daf-16 worms with age and find that daf-2 worms have an extended ability to learn for approximately 10 days longer than wild types. This was daf-16 dependent. Memory was extended in daf-2 as well, and strikingly, daf-2;daf-16 had no short-term memory even at day 1. Transcriptomic analysis of FACS-sorted neurons was performed on the three groups at day 8. The authors focus their analysis on daf-2 vs. daf-2;daf-16 and present evidence that daf-2 neurons express a stress-resistance gene program. One question that remains unanswered is how well the N2 and daf-2;daf-16 correlate overall, and are there differences? This may be informative as wild type and daf-2;daf-16 mutants are not phenotypically identical when it comes to memory, and there may be differences that can be detected despite the overlap in the PCA. This analysis could reveal the daf-16 targets involved in memory.

Re. daf-2;daf-16 vs N2: This is a good suggestion. Our analysis in Fig. S5 showed that the daf-2 vs N2 comparison shows similar results with the daf-2 vs daf-16;daf-2 comparison, but some additional genes are differentially expressed. Interestingly, the daf-2 vs N2 comparison shows that the bZip transcription factors are upregulated in daf-2 compared with N2 worms (Fig. S6f). This may indicate that additional transcription factors are controlled by the daf-2 mutation in the nervous system in addition to the DAF-16/FOXO transcription factor.

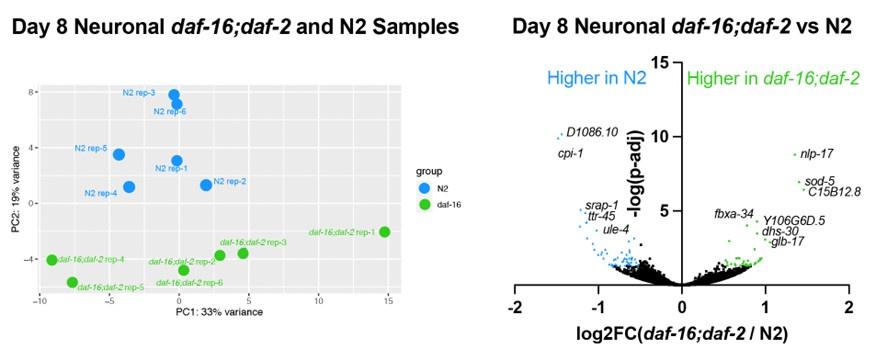

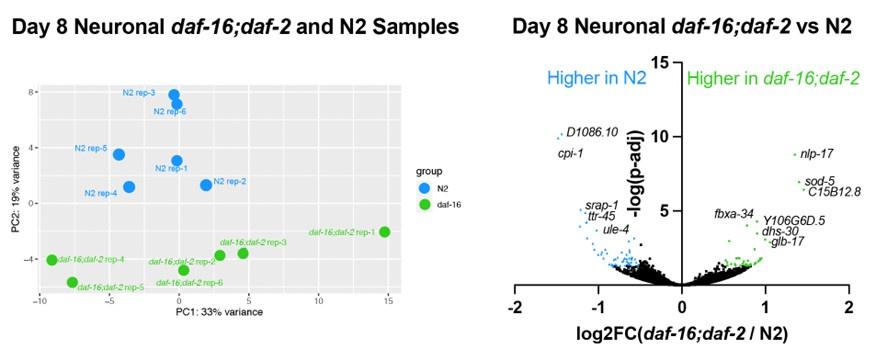

Author response image 1.

We also identified the differentially expressed genes in the Day 8 neuronal daf-16;daf-2 to N2 comparison, as the reviewer is asking about. The samples from different genotypes do separate from one another in the PCA plot, indicating there are differences between daf-16,daf-2 and N2 neurons. However, the difference is smaller and there are fewer genes differentially expressed between daf-16;daf-2 and N2: only 38 genes are significantly higher in daf-16;daf-2, and only 53 genes are significantly higher in N2 (log2FC > 0.5, p-adj<0.05). The genes higher in N2 are enriched in endopeptidase inhibitors, and the genes higher in daf-16;daf-2 are not enriched in any gene ontology terms. These results indicate that there are some differences between daf-16;daf-2 and N2 neurons, which correlates with the behavioral differences we see, but the difference is small compared to daf-2 neurons. We have added these data to the paper (Fig. S4e,f); thank you for the suggestion.

The authors tested eight candidate genes that were more highly expressed in daf-2 neurons vs. daf-2;daf-16 and showed that reduction of 2 and 5 of these genes impaired learning and memory, respectively, in daf-2 worms. This finding implicates specific neuronal transcriptional targets of IIS in maintaining cognitive ability in daf-2 with age, which, importantly, are distinct from those in young wild type worms.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Weng et al. perform a comprehensive study of gene expression changes in young and old animals, in wild-type and daf-2 insulin receptor mutants, in the whole animal, and specifically in the nervous system. Using this data, they identify gene families that are correlated with neuronal ageing, as well as a distinct set of genes that are upregulated in neurons of aged daf-2 mutants. This is particularly interesting as daf-2 mutants show both extended lifespans and healthier neurons in aged animals, reflected by better learning/memory in older animals compared with wild-type controls. Indeed, the knockdown of several of these upregulated genes resulted in poorer learning and memory. In addition, the authors showed that several genes upregulated during ageing in wild-type neurons also contribute to learning and memory; specifically knockdown of these genes in young animals resulted in improved memory. This indicates that (at least in this small number of cases), genes that show increased transcript levels with age in the nervous system somehow suppress memory, potentially by having damaging effects on neuronal health.

Finally, from a resource perspective, the neuronal transcriptome provided here will be very useful for C. elegans researchers as it adds to other existing datasets by providing the transcriptome of older animals (animals at day 8 of adulthood) and demonstrating the benefits of performing tissue-specific RNAseq instead of whole-animal sequencing.

Thank you!

The work presented here is of high quality and the authors present convincing evidence supporting their conclusions.

Thanks!

I only have a few comments/suggestions:

(1) Do the genes identified to decrease learning/memory capacity in daf-2 animals (Figure 4d/e) also impact neuronal health? daf-2 mutant worms show delayed onset of age-related changes to neuron structure (Tank et al., 2011, J Neurosci). Does knockdown of the genes shown to affect learning also affect neuron structure during ageing, potentially one mechanism through which they modulate learning/memory?

Thank you for this suggestion, which would be good for a future direction, particularly for genes that might have some relationship to previously-identified cellular structural process. The genes we tested here include dod-24, alh-2, mtl-1, F08H9,4, C44B7.5, hsp-12.3, hsp-12.6, and cpi-1, which are related to stress response, proteolysis inhibitor, metabolic, and innate immunity GO categories, thus associated with stress resistance, proteolysis, lipid metabolism processes; none are obvious choices for morphological effects.

However, it is worth noting that learning and memory decline much faster (Days 4-8) than morphological differences are observed (generally after Day 12-15). Moreover, those morphological differences have been studied primarily in mechanosensory neurons (touch neurons) rather than the chemosensory neurons that are involved in learning and memory, so additional genes may be required for those differences that we were not focusing on in thisi study.

(2) The learning and memory assay data presented in this study uses the butanone olfactory learning paradigm, which is well established by the same group. Have the authors tried other learning assays when testing for learning/memory changes after the knockdown of candidate genes? Depending on the expression pattern of these genes, they may have more or less of an effect on olfactory learning versus for example gustatory or mechanosensory-based learning.

The reason that we use the butanone olfactory learning paradigm is because it is more similar to learning of information (neutral odorant association with positive cue (food)) – the kind of memory we would like to preserve in humans - rather than a stress-induced memory, such as starvation or pathogenesis-associated aversive learning paradigms, which are more like PTSD. (There is likely to be quite a bit of overlap in mechanism, however, including the role of genes such as magi-1 and casy-1, so it would not be surprising if many of these genes also were required for other learning paradigms.)

(3) I have a comment on the 'compensatory vs dysregulatory' model as stated by the authors on page 7. I understand that this model presents the two main options, but perhaps this is slightly too simplistic: the gene expression that rises during ageing may be detrimental for memory (= dysregulatory), but at the same time may also be beneficial for other physiological roles in other tissues (=compensatory).

This is a good point, and we made the clarification that in the text: “There may be other scenarios in which a gene with multiple functions may be detrimental for some behaviors but beneficial for other physiological roles.”

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, Weng et al. detect a neuron-specific transcriptome that regulates aging. The authors first profile neuron-specific responses during aging at a time point where a loss in memory function is present. They discover signatures unique to neurons which validate their pipeline and reveal the loss of neuron identity with age. For example, old neurons reduce the expression of genes related to synaptic function and neuropeptide signaling and increase the expression of chromatin regulators, insulin peptides, and glycoproteins. The authors discover the detrimental effect of selected upregulated genes (utx-1, ins-19, and nmgp-1) by knocking them down in the whole body and detecting improvement of short memory functions. They then use their pipeline to test neuronal profiles of long-lived insulin/IGF mutants. They discover that genes related to stress response pathways are upregulated upon longevity (e.g. dod-24, F08H9.4) and that they are required for improved neuron function in long-lived individuals.

Strengths:

Overall, the manuscript is well-written, and the experiments are well-described. The authors take great care to explain their reasoning for performing experiments in a specific way and guide the reader through the interpretation of the results, which makes this manuscript an enjoyable and interesting read. Using neuron-specific transcriptomic analysis in aged animals the authors discover novel regulators of learning and memory, which underlines the importance of cell-specific deep sequencing. The time points of the transcriptomic profiling are elegantly chosen, as they coincide with the loss of memory and can be used to specifically reveal gene expression profiles related to neuron function. The authors showcase on the dod-24 example how powerful this approach is. In long-lived insulin/IGF-1 receptor mutants body-wide dod-24 expression differs from neuron-specific profiles. Importantly, the depletion of dod-24 has an opposing effect on lifespan and learning memory. The dataset will provide a useful resource for the C. elegans and aging community.

Thank you, we do hope people will find the data useful.

Weaknesses:

While this study nicely describes the neuron-specific profiles, the authors do not test the relevance in a tissue-specific way. It remains unclear if modifying the responses only in neurons has implications for either memory or potentially for lifespan. The authors point to this in the text and refer to tissue-specific datasets. However, it is possible that the tissue-specific profile changes with age. The authors should consider mining publicly available cell-specific aging datasets and performing neuron-specific RNAi to test the functional relevance of the neuron-specific response. This would strengthen the importance of cell-specific profiling.

Thank you for your suggestions. As we have mentioned in the text, our candidate genes are either (1) only expressed in the neurons (alh-2 and F08H9.4), or they are only more highly expressed in daf-2 compared to wild type only in the nervous system (C44B7.5 or dod-24). Thus, the effect we see from knocking down these genes in daf-2 are likely neuron-specific. Additionaly, we performed our assays with neuron-sensitive RNAi strain CQ745: daf-2(e1370) III; vIs69 [pCFJ90(Pmyo-2::mCherry + Punc-119::sid-1)] V. It has been previously shown that neuronal expression of sid-1 decreases non-neuronal RNAi, suggesting that neurons expressing transgenic sid-1(+) served as a sink for dsRNA (Calixto et al., 2010). Thus, this neuron-sensitive RNAi is likely neuron-specific and our results is unlikely from knocking down these genes in non-neuronal tissues. However, we do acknowledge this issue.

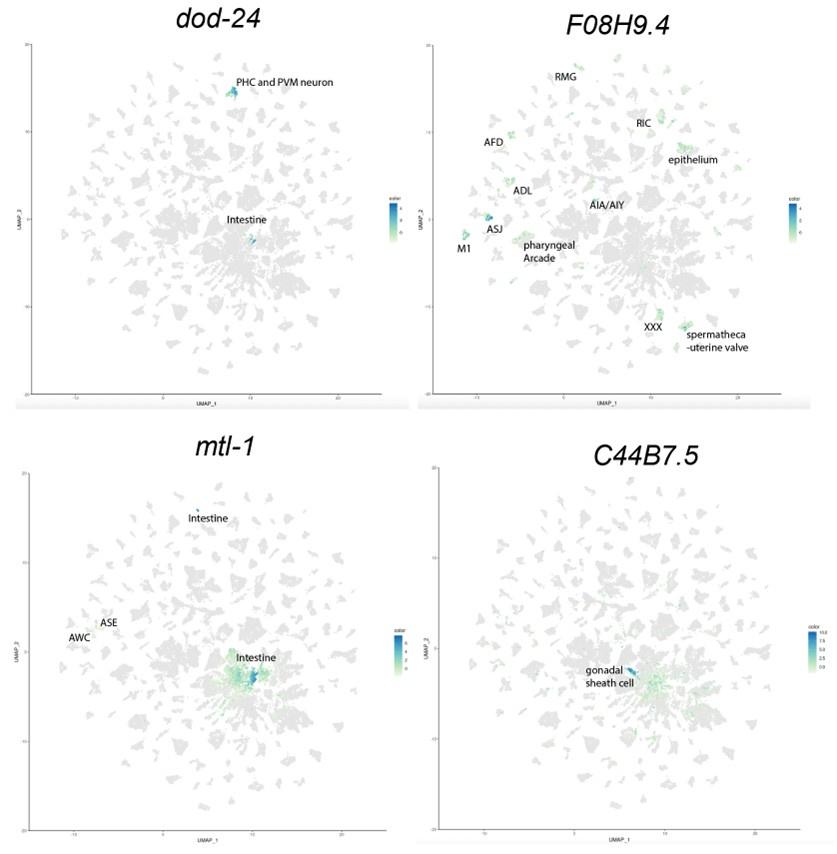

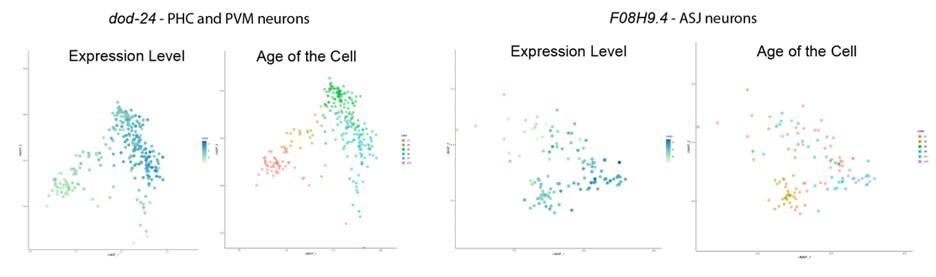

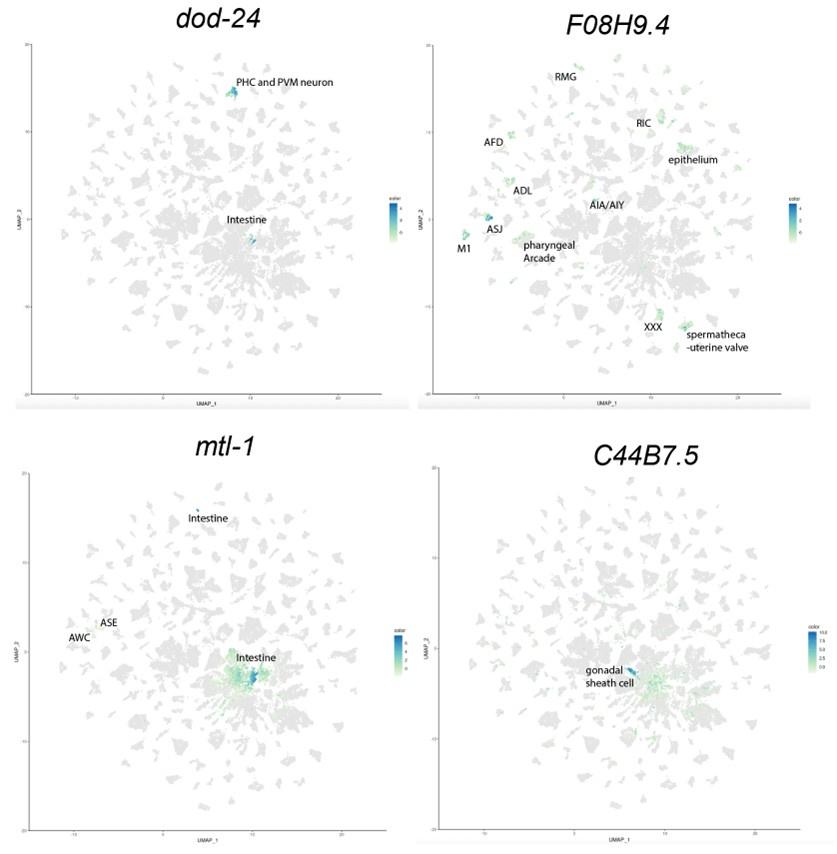

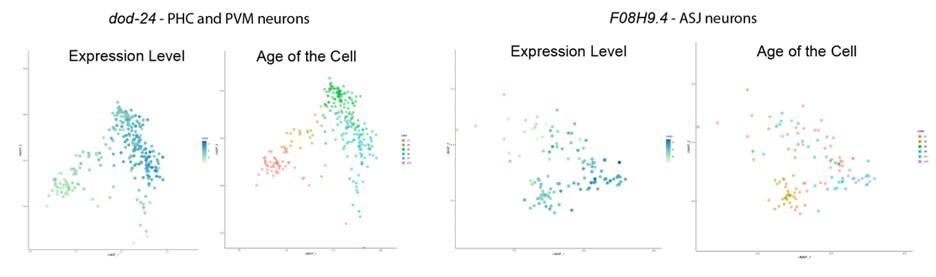

To identify the expression pattern of these genes in a more cell-specific way in the adults, we examined the expression of our candidate genes that affected learning and memory, namely dod-24, F08H9.4, C44B7.9, alh-2, and mtl-1, in the Calico database (Roux et al., 2023). From that database, we can see that dod-24 is mainly expressed in the PHC and PVM neurons, and F08H9.4 is largely expressed in various neurons. Both have only slight expression outside the nervous system. C44B7.5 and mtl-1 are more broadly expressed, but C44B7.5 was not found to be differentially expressed in other tissues in daf-2, and mtl-1 only had a slight effect on learning and memory. Perhaps due to their sequencing depth and detection limit, Roux et al. didn’t detect alh-2 expression anywhere in their data.

Thus, the neuron-specific expression and daf-2 differential expression pattern of these genes indicate that the learning and memory improvement in aged daf-2 is unlikely due to neuronal non-autonomous effects.

To better address this concern (that for the genes that we found only expressed in the neurons, the neuron-confined expression may change with age) we examined the expression pattern change of these genes with age. As is shown below, from the Calico database, we can see that the expression in the nervous system persists, and even slightly increases, with age, thus age-related expression pattern change is not a concern to our analysis.

Author response image 2.

Author response image 3.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Most of my comments are in the public section. A few additional recommendations for the authors regarding the formatting/presentation:

The presentation of Figure S6e-h in the introduction is somewhat confusing and feels out of order. If presented first, it should be S1. Otherwise, discussion of this figure should go at the end of the results section or in the discussion if appropriate.

Thank you for pointing this out. We have moved the discussion of this figure to the Discussion section.

I do not see Figure S5 described in the text.

Good catch, thank you. We have added the descriptions for Figure S5 in the text.

In general, check the figures, figure legends, and how they are referenced in the text, particularly the supplemental figures and legends.

Minor comments:

There is a typo in the Figure 4 legend: Neuronal IIX should be IIS.

Thanks for pointing this out. We have corrected it in the text.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

• There are multiple instances throughout the manuscript where there are statements in brackets that provide justification or explanation for some of the approaches used. There is no reason for 'side note' brackets to be used. I suggest removing them and incorporating these statements into the narrative.

Thank you, we have now incorporated these points into the main text.

• Introduction: page 4 "here we RNA-sequenced FACS-isolated neurons" should be "here we performed RNA sequencing on FACS-isolated neurons...".

Thank you, we have changed the text accordingly.

• Figure 2A: I do not understand the legend for this panel "Tissue Query for wild-type genes expressed at higher levels in aged worms show lower nervous system and neuron prediction score." Please clarify.

We have clarified the Figure 2A legend:

(A) Tissue prediction score for wild-type genes expressed at higher levels in aged worms.

• Page 8: "We previously observed that loss of single genes that play a role in complex behaviors like learning and memory can have a large impact on function 60, unlike the additive roles of longevity-promoting genes 11." - a large impact on what function?

Thank you for noting, we have clarified it in the text accordingly:

“We previously observed that for genes that play a role in complex behaviors like learning and memory, the loss of single genes can have a large impact on these complex behaviors 60, unlike the additive roles of longevity-promoting genes 11.”

• Next line "Therefore, one mechanism by which wild-type worms lose their function with age..." - again, what function?

Thank you for noting this, we have clarified the text to say we refer to the learning and memory functions.

• Page 9: "Thus, daf-2 mutants maintain their higher cognitive quality of life longer than wild-type worms, while daf-16;daf-2 mutants spend their whole lives without memory ability (Figure 3d), in contrast to claims that daf-2 mutants are less healthy than wild-type or daf-16 worms23." - since ref 23 did not perform any learning/memory tests, the definition of 'health' in ref 23 is different to 'cognitive health' as studied here. So the findings in this study are not 'in contrast' to ref 23 but rather add to these findings.

Learning and memory ability is an important function for a healthy individual, thus we would assert that indeed, cognitive health is an important part of the “health” of daf-2 worms. In ref 23, Bansal et al. claim that daf-2 worms are less healthy without assessing their learning and memory ability; their lack of data is an insufficient reason for us to remove our statement, as cognitive health is part of healthspan. Here we find that the “learning span” of daf-2 lasts at least proportionally if not longer than that of wild type. We have also previously shown that daf-2 worms also have longer maximum velocity span with age (Hahm et al., 2015), in direct contrast with Bansal et al.’s claim that daf-2 worms move less well and thus are less healthy – daf-2 worms simply stop sooner when presented with food and switch to feeding, due to their higher odr-10 levels. The Bansal paper continues to be frequently cited as finding that daf-2 mutants are less healthy than wild type, a claim for which we can still find no experimental evidence to support. Therefore, it is important that we make the point that daf-2 worms have extended cognitive health, which is part of health span.

• Page 13: I feel like the sentence "Furthermore, memory maintenance with age might require additional functions that were not previously uncovered in analyses of young animals" is both vague (what functions are referred to?) and a little bit obvious (obvious that age-related changes would not be revealed in analyses of young animals). Perhaps rephrase to make the desired point clearer?

We have clarified the sentence in the text:

“Furthermore, memory maintenance with age might require additional genes that function in promoting stress resistance and neuronal resilience, which were not previously uncovered in analyses of young animals.”