Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorErika BachNYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, United States of America

- Senior EditorFelix CampeloUniversitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

The authors want to determine the role of the sperm hook of the house mouse sperm in movement through the uterus. They use transgenic lines with fluorescent labels to sperm proteins, and they cross these males to C57BL/6 females in pathogen-free conditions. They use 2-photon microscopy on ex vivo uteri within 3 hours of mating and the appearance of a copulation plug. There are a total of 10 post-mating uteri that were imaged with 3 different males. They provide 10 supplementary movies that form the basis for some of the quantitative analysis in the main body figures. Their data suggest that the role of the sperm hook is to facilitate movement along the uterine wall.

Strengths:

Ex vivo live imaging of fluorescently labeled sperm with 2-photon microscopy is a powerful tool for studying the behavior of sperm.

Weaknesses:

The paper is descriptive and the data are correlations.

The authors cannot directly test their proposed function of the sperm hook in sliding and preventing backward slipping.

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Thank you for your time and consideration on our submission. We also thank the reviewers for their consideration and helpful comments. We have revised the introduction, results, and discussion sections of the revised manuscript in accordance with the reviewers’ suggestions, which have enhanced the clarity of our work. Specifically, we have clarified that the aim of the study is to report newly discovered sperm behaviours inside the uterus via high resolution deep tissue live imaging, and to stimulate further studies and discussion in the field of postcopulatory sexual selection in mice based on our observations. To the best of our knowledge, many of the specific sperm behaviours described in our manuscript are being reported for the first time, proven through direct observation inside the living reproductive tract.

We have also restructured our manuscript and moved our hypothetical interpretations based on our experimental observations to the discussion section. We hope that these revisions have clarified our claims and that our revised manuscript effectively communicates the importance of our findings and its values in prompting new questions and insight that encourage further studies. We believe that our work clearly demonstrates the importance of sperm/reproductive tract interaction, which cannot be adequately studied in artificial environments, and may become an important guideline for designing future experiments and studies.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

The authors want to determine the role of the sperm hook of the house mouse sperm in movement through the uterus. The authors are trying to distinguish between two hypotheses put forward by others on the role of the sperm hook: (1) the sperm cooperation hypothesis (the sperm hook helps to form sperm trains) vs (2) the migration hypothesis (that the sperm hook is needed for sperm movement through the uterus). They use transgenic lines with fluorescent labels to sperm proteins, and they cross these males to C57BL/6 females in pathogen-free conditions. They use 2-photon microscopy on ex vivo uteri within 3 hours of mating and the appearance of a copulation plug. There are a total of 10 post-mating uteri that were imaged with 3 different males. They provide 10 supplementary movies that form the basis for some of the quantitative analysis in the main body figures. Their data suggest that the role of the sperm hook is to facilitate movement along the uterine wall.

We thank the reviewer for summarizing our work and the critical review of our paper. As summarized, the sperm hook has been primarily associated with the sperm cooperation (sperm hook) hypothesis and the migration hypothesis. However, we would like to emphasize that the aim of our work is not to cross check between the two hypotheses. Our aim was not to disprove either hypothesis, but rather to develop an experimental platform that enables detailed observation of sperm migration dynamics within the live reproductive tract.

Through live imaging, we observed both the formation of sperm trains as well as interaction between the sperm and female reproductive tract epithelium. However, in our observations, we could not find advantage in terms of faster movement for the rarely observed sperm trains. While these events were infrequent in our experiments, we are not asserting that the sperm train hypothesis is invalid but rather reporting our observations as is.

The main findings of our work lie in the newly observed dynamic behaviours of mouse sperm interacting with the female reproductive tract epithelium. Specifically, tapping and associated guided movement along the uterus wall, anchoring and related resistance to internal fluid flow and migration through the utero-tubal junction, and self-organized behaviour while clinging onto the colliculus tubarius. We have extensively revised the manuscript structure to clarify our findings.

Strengths:

Ex vivo live imaging of fluorescently labeled sperm with 2-photon microscopy is a powerful tool for studying the behavior of sperm.

Weaknesses:

The paper is descriptive and the data are correlations.

The data are not properly described in the figure legends.

When statistical analyses are performed, the authors do not comment on the trend that sperm from the three males behave differently from each other. This weakens confidence in the results. For example, in Figure 1 the sperm from male 3613 (blue squares) look different from male 838 (red circles), but all of these data are considered together. The authors should comment on why sperm across males are considered together when the individual data points appear to be different across males.

Thank you for your comments and suggestions. We have revisited all figure legends and made the necessary amendments (shown in the red-lined manuscript). Please note that, for a better flow of the paper, the previous Figure 1 has been changed to Figure 2 in the revised manuscript.

Regarding the analysis using different males, we would like to explain the statistics used. We used generalized linear mixed models to test the effect of the Angle and Distance to the wall on the migration kinetic parameters. The advantage of the generalized linear mixed models is that they consider individual variations in the data as an error term, thereby controlling such individual variations.

There are two main factors contributing to individual variations. One is, as you pointed out, the difference in sperm from different males. However, we used genetically similar mice, so genetical variations must be minimal. Nonetheless, there must be individual differences that caused variations including age, stress level as well as body conditions. As these factors cannot be controlled, we used the mixed model approach where individual variations are grouped within the individual. This approach enabled us to test the effect of each explanatory variable (Angle and Distance) within an individual.

The second factor that could cause variations is the female oestrous status. To avoid artifacts that could influence sperm behaviour, we did not use any invasive methods, such as hormone injections, to control or induce female oestrus. We controlled for this possible effect by including the mating date as a random effect. Since each female was used only once, the mating date reflects the variation caused by each female.

To provide further verification that the variation between individual males do not affect our results, we conducted analysis per individual male and mating dates (per each female). As clearly shown, sperm data points from individual males or female also show consistent clear correlations with the distance from the uterus wall. As pointed out, while the mean sperm speed could be different between individuals, they are not the topic we are interested in here. Our interest here is the effect of the distance between sperm and the uterine wall. Additionally, the variation between males is not always larger than those effect of the day (female), which in total suggest that integrating male variation is not essential. We have added this information to Supplementary Figure (Fig. S3) of the revised supplementary materials.

Moving forward, we can also consider the same analysis for the effects of the distance from wall on sperm SWR and LIN (linearity of forward progression) where no statistical significance was found. As see in the following figures, no statistically significant effect of the distance to wall on SWR and LIN are seen in that the regression lines drawn for each male and mating dates.

In summary, the statistical approach we used here has successfully reflected variations in sperm kinetics from different males as well as the variance from different females. We hope that our explanations and additional analysis answer your concerns.

Movies S8-S10 are single data points and no statistical analyses are performed. Therefore, it is unclear how penetrant the sperm movements are.

With respect to Movie S8, Figure 4A and B (Figure 5A and B in the current revised manuscript) depict the trajectories of accumulated spermatozoa (sperm trains) in the female uterus, as shown in Movie S8. We have added this information to the revised figure legend (L 293) for clarity. We could not observe sperm trains that moved faster than single sperms during over 100 hours of observation and collection of over 10TB of images. The three sperm trains presented in Fig. 5B were the sperm trains that moved in the head-forward direction. Most other identifiable trains, or clusters, did not move or could not move forward as their heads were entangled randomly. Although we of course agree that a statistical test for Movie S8 (also Fig. 5B) would be great, due to the small number of sperm trains we found, we could not perform meaningful statistical tests. Instead, we provided all data in the box plots in Fig. 5C so that readers can evaluate and understand our points. We believe that this is a more neutral way of presenting our data rather than providing statistical significance.

Regarding Movies S9 and S10, we are not entirely sure whether we understood your comments clearly. It would be very helpful if you could point out more specifically to the manuscript with line numbers as we would like to address your concerns and suggestions, and we believe that your input will improve our manuscript. We did not describe the penetration of sperm in these movies. Movies S9 and S10 are newly found sperm behaviours inside the UTJ and Isthmus. We observed that sperm beating is influenced by the width of luminal space as well as internal flow as see in Movies S9 and S10. As our animal model only expresses red fluorescence in the midpiece, accurate beating frequency measurement cannot be performed. However, we can clearly observe that beating is not continuous and almost results in a halt with respect to reproductive tract variations. We revised our description about the findings about beating speed changes in the revised manuscript (LL 305-335).

Movies S1B - did the authors also track the movement of sperm located in the middle of the uterus (not close to the wall)? Without this measurement, they can't be certain that sperm close to the uterus wall travels faster.

We revised the new Movie S1B to include videos that were used for the sperm migration kinetics analysis in Figure 2 (previously Figure 1). As you can see in the movies, the graph, and statistical analysis, there is a clear trend showing spermatozoa migration is slower as a function of distance from the uterus wall. Regarding your comment with respect to the middle of the uterus (not close to the wall), we have added another movie (Movie S1C) that was acquired at different depths from the wall (going towards the centre of the uterus). As clearly seen in Movie S1c, when imaging deeper into the uterus, there are an increasing number of inactive or slow-moving spermatozoa. Since the diameter of the uterus is easily over 2mm, we currently do not have optical access to exactly the centre of the uterus, but for all depths that are observable, spermatozoa near the wall were clearly faster.

Movie S5A - is of lower magnitude (200 um scale bar) while the others have 50 and 20 uM scale bars. Individual sperm movement can be observed in the 20 uM (Movie 5SC). If the authors went to prove that there is no upsucking movement of sperm by the uterine contractions, they need to provide a high magnification image.

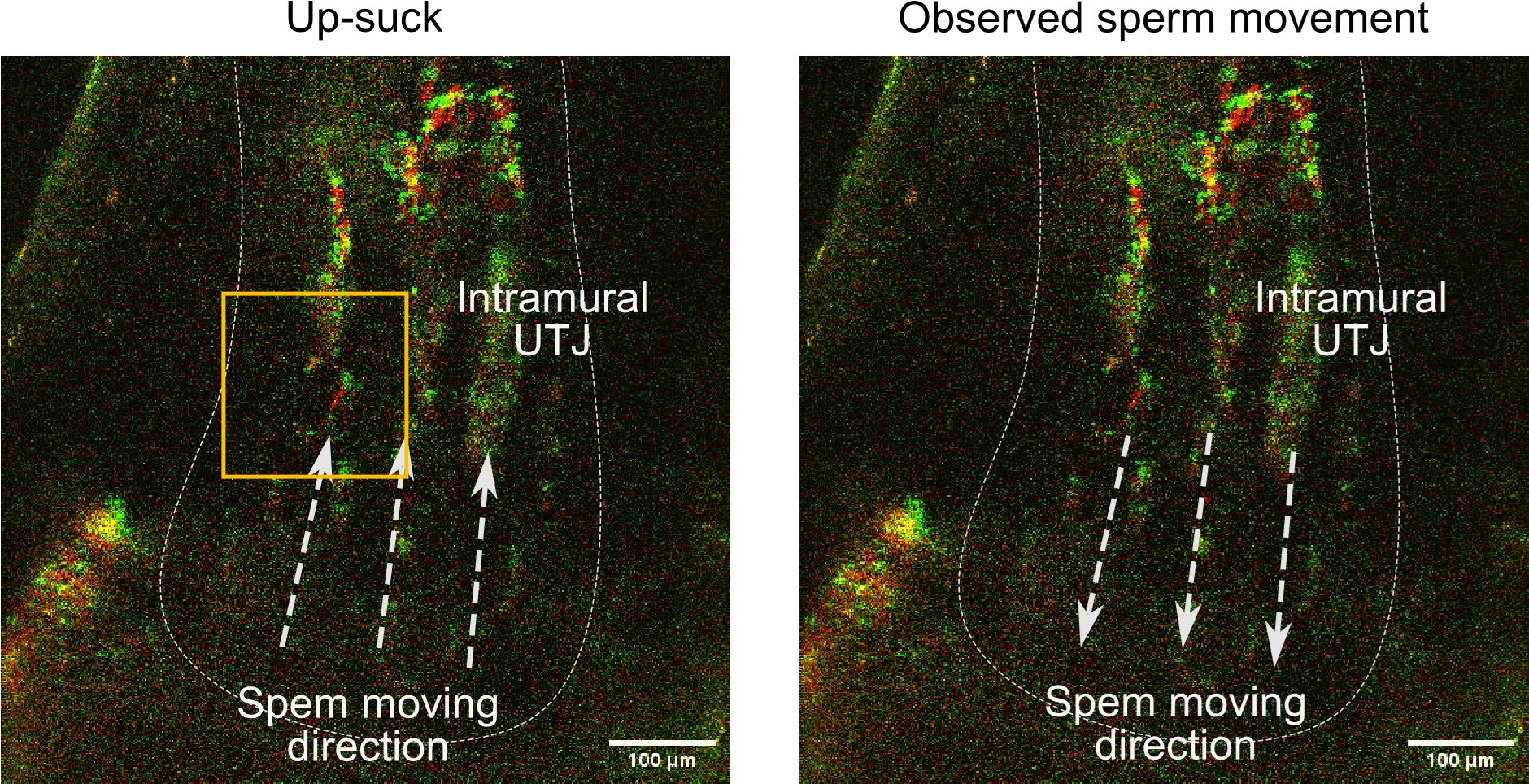

The main focus of video S5A, is the intramural UTJ where spermatozoa are located in rows within narrow luminal space (see Author response image 1). When there is up-suck like sperm passive carriage, there must be sperm movement from the uterus to intramural UTJ as in Author response image 1 left. However, there is no such sperm movement could be seen in our observations, as shown in Movie 5A. Importantly, as you can see in Movie 5A, indicated by an arrow from 5 sec to 6 sec, some spermatozoa are moving downward (see also Author response image 1 right). This is the opposite direction of movement with respect to possible up-suck like sperm carriage.

Genetical evidence also support up-suck like passive sperm carriage is not the case for sperm migration from the uterus to UTJ. If environmental up-suck like passive transfer plays an important role, it is unlikely that genetically modified spermatozoa cannot pass the entrance of the intramural UTJ (Nakanishi et al., 2004, Biol. Reprod.; Li et al., 2013, J. Mol. Cell Biol.; Larasati et al., 2020, Biol. Reprod.; Qu et al., 2021, Protein Cell).

Author response image 1.

The left image represents what is expected when up-suck like passive sperm carriage occurs. The right image represents what is actually experimentally observed in the intramural UTJ (see Movie S5A). The direction of the arrowheads indicates the direction of sperm movement.

Movie S8 - if the authors want to make the case that clustered sperm do not move faster than unclustered sperm, then they need to show Movie S8 at higher magnification. They also need to quantify these data.

We understand your concern. As shown in Figure 5B, we included all sperm kinetics data of each sperm train and unlinked spermatozoon around the trains as individual dots. The only analysis we did not conduct was a statistical test with the data as it could be erroneous due to the large sample size difference (3 trains vs 181 unlinked spermatozoa). As the medians of the four sperm kinetic parameters are similar except SWR, we concluded that they are not necessarily faster than unlinked single spermatozoa. Since there is no known advantage to spermatozoa (including sperm trains) with intermediate moving speeds for sperm competition – for example in IVF, success fertilization rate is high when faster and active spermatozoa with normal shape are selected (Vaughan & Sakkas, 2019, Biol. Reprod.) – it is questionable whether there can be an advantage to the formation of sperm trains whose speed is not faster than unlinked spermatozoa in our data.

However, we do not agree with your comment regarding the need for higher magnification. Measurement of the sperm migration speeds (kinetic parameters) does not require measurement of exact tail movements in this study. Only sperm heads were tracked to measure their trajectory and such tracking was better done at low mag. For example, measuring the speed of a car does not need higher magnifications to visualize the rotation of the wheels. Additionally, including the effect of observation magnification on the sperm kinetic parameters for all 4 GLMM models for Figure 2 (Table S3) does not change the result, which shows that magnification is not a factor that influences our analysis.

Movie S9C - what is the evidence that these sperm are dead or damaged?

Thank you for your valid comment. We tracked sperm movements for at least 10 minutes and such entangled spermatozoa in the UTJ never became re-active. As you can see in the new Movie S9b, entangled spermatozoa were also acrosome re-acted (green acrosome head is gone) while active spermatozoa are responding to peristaltic movement by exhibiting movements within the same video. However, as you pointed out, we did not measure their viability with appropriate dyes. Although we also considered about extracting these spermatozoa and performing viability tests, we could not come up with a way to specifically extract the exact spermatozoa that were imaged. Considering your comments, we changed the term damaged or dead to inactive in the revised manuscript (LL 313-316, Legend Figure 6D. LL 380-384).

Movie S10 - both slow- and fast-moving sperm are seen throughout the course of the movie, which does not support the authors' conclusion that sperm tails beat faster over time.

There must have been a misunderstanding. We did not indicate that sperm beating got faster over time anywhere in the main manuscript, including the figure legend and related movie captions. As correctly pointed out, the sperm beating speed changes over time (not getting faster over time) and shows a correlation with internal fluid flow and width of luminal space (LL 320-332). Please let us know if you meant something else.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

The specific objective of this study was to determine the role of the large apical hook on the head of mouse sperm (Mus musculus) in sperm migration through the female reproductive tract. The authors used a custom-built two-photon microscope system to obtain digital videos of sperm moving within the female reproductive tract. They used sperm from genetically modified male mice that produce fluorescence in the sperm head and flagellar midpiece to enable visualization of sperm moving within the tract. Based on various observations, the authors concluded that the hook serves to facilitate sperm migration by hooking sperm onto the lining of the female reproductive tract, rather than by hooking sperm together to form a sperm train that would move them more quickly through the tract. The images and videos are excellent and inspirational to researchers in the field of mammalian sperm migration, but interpretations of the behaviors are highly speculative and not supported by controlled experimentation.

Thank you for your critical review and valuable comments on our manuscript. As pointed out, some of our findings and suggestions were largely observation based. However, to the best of our knowledge, many of our observations are novel, particularly in the context of live imaging inside the female uterus and reproductive tract. We believe these observations open doors to many questions and follow up studies that can be envisioned based on our findings, which is what drives science forward.

That being said, we entirely agree that many follow up experiments need to be designed and performed, especially to validate the exact molecular mechanisms of the observed dynamics. We acknowledge that it is unfortunate we currently lack the proper molecular experimental toolsets to perform further tests. We have removed much of the hypothetical discussions from the results section and moved them to the discussion section. We hope that our revision more clearly defines the observed experimental data and our interpretations.

Strengths:

The microscope system developed by the authors could be of interest to others investigating sperm migration.

The new behaviors shown in the images and videos could be of interest to others in the field, in terms of stimulating the development of new hypotheses to investigate.

Weaknesses:

The authors stated several hypotheses about the functions of the sperm behaviors they saw, but the hypotheses were not clearly stated or tested experimentally.

The hypothesis statements were weakened by the use of hedge words, such as "may".

We appreciate your helpful comments and have revised our hypotheses and suggestions accordingly. We have removed instances of “may” or revised it to be more direct. We have also moved most of our interpretations and hypotheses from the results to the discussion section.

It is important to note that experimental approaches to test what we suggested from our findings in the current ex-vivo observation platform are not trivial and require extensive investigation of several unknown factors of the female reproductive tract. For instance, obtaining detailed information on the chemical characteristics and fluid dynamics in the female reproductive tract is essential to build a microfluidic channel that accurately resembles the uterus and oviduct, replicating what we found in an extracted living entire organ. This poses a significant challenge and requires collaborative expertise from many labs, which we hope to build in the near future.

Furthermore, our biggest concern is that, even if we were to construct the appropriate microfluidic channel to test sperm migration, it is very likely that the sperm behaviours that we observed under natural conditions may not be replicated in artificial environments. This raises questions about whether in-silico or in-vitro findings can truly resemble what we reported here using the ex-vivo observation inside a living organ.

To share our experience related to this difficulty, at the initial stage of our study, we attempted sperm injection combined with fluorescent beads to visualize the fluid flow, as well as dyeing the female reproductive tract and spermatozoa after mating. However, none of these resulted in meaningful results. Another potential approach to perform similar research regarding our claims is using genetical engineering to indirectly confirm the influence of the sperm hook morphology on sperm behaviour. However, such an approach lacks a mechanical demonstration about how the sperm hook interacts with the female reproductive tract.

It is unfortunate that the sperm behaviours that we found and reported here are considered as highly speculative. The main findings of our work lie in the newly observed dynamic behaviours of mouse sperm interacting with the female reproductive tract epithelium. Specifically, these behaviours include tapping and associated guided movement along the uterus wall, anchoring and related resistance to internal fluid flow and migration through the utero-tubal junction, and self-organized behaviour while clinging onto the colliculus tubarius.

We have extensively revised the manuscript structure to clarify our findings and integrated our points in the introduction. Although we understand our following hypotheses may be considered speculative and the causative relationship between the sperm hook and its role in sperm migration requires further experimental approaches, we believe that the image-based observation of dynamic behaviours of spermatozoa are solid. We believe our findings will facilitate further studies and discussion in the field of studies on postcopulatory sexual selection in rodents.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

The manuscript is written for an expert in a fairly small field. I recommend that the authors rewrite the manuscript to make it more accessible to people outside of the field. These suggestions include

(1) Provide a diagram of the female reproductive tract in Figure 1.

a. Indicate where sperm enter the tract and the location of the oocyte they are trying to reach.

b. Label all areas of the uterus that are mentioned in this study and be consistent about the label.

(2) All movies should have a diagram of the location of the uterus that is being imaged.

Thank you for the great suggestion. We have added a diagram of the female reproductive tract in the revised Figure 1A. In response to your comments 1a and b, we have indicated such information by including eggs in the ampulla and arrows that indicate sperm migration direction. We have also labelled the name of the specific areas that were studied in the manuscript.

We are unsure how to integrate the diagram in all movies without reframing the videos, which could cause serious corruption of the files. More importantly, we think that adding the same diagram to all movies may complicate the visuals and disrupt indications and subject in the movie. Instead, we have referred to the common diagram (Figure 1A) in each movie caption, specifying where the video was taken. Thank you for the suggestion. With this information, we hope readers can now more easily understand where we made the observations.

(3) The major questions in the field need to be better described in the introduction.

Thank you for your valuable suggestions and specific comments which have greatly helped improve our manuscript. We have revised our introduction and discussion sections by adding more literature reviews and integrating studies across a wider range of the postcopulatory sexual selection, as per your suggestion (LL 34-57, LL 385-398).

(4) The major question that the authors are trying to address should be described in the introduction.

Thank you for the helpful suggestion. We have clarified in the introduction that our aim was to contribute to the field of postcopulatory sexual selection in rodents by advancing methodological progress and to stimulate discussion and future research on the function of the sperm hook in murine rodents (LL 76-94) based on our observations.

(5) A discussion of the sperm hook should be provided. How many species have this structure (or similar structure)?

We have integrated your point into the revised discussion section. Essentially, most murine rodent species have sperm hooks (while their exact shapes differ). However, as there are over 500 species and not all of them have been tested, we do not know exactly how many of them have this structure. Therefore, we included paper references that examined species variations in sperm hook characteristics and their possible correlation with sperm competition (LL 385417) in the discussion. Additionally, we also included papers by Breed (2004) and by Roldan et al (1992) that investigated murine rodents with a sperm hook in the introduction section as well (LL 58-61).

(6) The figure legends must describe everything in the figure or movie.

Thank you for the helpful suggestion. We previously thought that our figure legends may be too long. We have included further information in the figure legends and movie captions. We have also revised the movies by adding some clips following our revision (Movie S1).

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Here are some specific concerns I had about the clarity of approach to experiments and interpretations of results.

In the Introduction, the authors stated that the study was intended to determine the function of the hooks on the mouse sperm heads. However, in the Results section, the authors did not explain the rationale for the first set of experiments with respect to the overall objective of the study. In this experiment, the authors measured the velocities of sperm swimming in the uterus and found that the sperm moved faster when closer to the uterine wall (VCL, VSL). They concluded that migration along the uterine wall "may" be an efficient strategy for reaching the entrance to the uterotubal junction (UTJ) and did not explain how this related to the function of the hooks.

Thank you for your critical comment and guidance. We have changed the order of Figure 1 and Figure 2 and revised the result section to integrate your points. At the initial stage of the study, we expected to find evidence of the function of sperm trains in aiding sperm migration in the female uterus (which has not been observed in the live uterus; previous works were done invitro with extracted sperm from epididymis or uterus after mating). However, what we found was something unexpected: dynamic sperm hook related movements facilitating sperm migration inside the female uterus by playing a mechanical role in sperm interaction with the uterine wall. These results that were presented in the previous Figure 2 has been reorganized as the new Figure 1.

Based on this observation, our research later moved to clarify whether such sperm-epithelium interaction indeed helps sperm migration. This led us to measure sperm kinetics in relation to their distance and angle to the uterine wall. We have revised our introduction and result parts by integrating these points. We hope that our revision will answer your questions. We have also reduced the use of ‘may’ or ‘can’ in the results section. In the revised manuscript, we have moved such hypotheses to the discussion section and focused on what we observed in the results section.

The authors proposed that the sperm hook "may" play a crucial role in determining the direction of migration. When sperm encountered a uterine wall, significantly more changed migration direction toward the pro-hook direction than toward the anti-hook direction. In Figure 2B, sperm behavior is not visually understandable nor clearly explained.

Thank you for the helpful comments. We have removed “may” and “might” to make our claim clearer and more concise. We have also revised the previous Figure 2B by combining it with the previous Figure 2C (they have been combined into Figure 1C now). We have also revised Figure 1B by increasing the line thickness of the sperm trajectory of the pro-wall-hook direction and added the anti-wall-hook trajectory. We hope that these revisions make the figure easier to understand.

In Figure 2E, are the authors showing that the tip of the hook is caught between two epithelial cells? Please clarify the meaning of this figure.

Please clarify the difference between "tapping" and "anchoring".

Thank you for the detailed comments. As you pointed out, we currently have no evidence whether sperm can be caught in epithelia inter-cellular gaps. We have revised this source of confusion by removing the gap in the revised figure (Figure 1E). We have also included the definition of anchoring (LL 142-143) and tapping (LL 128-130). Anchoring facilitates the attachment of sperm to the uterine epithelia. Such anchoring also involves the catching of the sperm head in the inter-mucosal fold or gap, particularly at the entrance of the intramural UTJ at the end of the uterus. Tapping is the interaction between the head hook and epithelia in which the sperm hook is tapping (or patting) on the surface. Sperm tapping can be a byproduct that results from flagella beating when spermatozoa migrate toward the pro-wall-hook direction along the uterine wall (epithelia) or can play some role in sperm migration. As we currently cannot draw a conclusion, we did not integrate the possible function of the tapping in the manuscript.

The authors proposed that opposite sliding of neighboring mucosal folds lining the UTJ would cause small openings to form, through which only perhaps one sperm at a time could enter and pass through the UTJ into the uterus. This hypothesis was not actually tested.

Imaging inside deep tissue is challenging due to light scattering as it penetrates through biological tissue. While this is also true for the uterus, the intramural UTJ is especially difficult to image because the UTJ consists of several thick muscle and cell layers (see Movie S5A). Another challenge is that the peristaltic movement of the UTJ results in constant movement, making continuous tracking of single sperms while passing through the entirety of the UTJ impossible in our current experiments. We have moved this hypothesis to the discussion section and restated that this is a pure hypothetical model (LL 399-406). We hope that our model encourages the community in designing or establishing an improved ex-vivo observation system that may be able to test this hypothetical model in the near future.

Next, the authors hypothesized that sperm that encounter the small openings in the UTJ may then be guided onward and the hooks could prevent backward slipping. This was also not tested.

As you’ve noted, the function of the sperm hook that aids in sliding and preventing backward slipping could not be tested directly in our ex-vivo observation platform that relies on natural movement of the living organ. However, we believe that these limitations also highlight the importance of continued research and the development of more advanced methodologies in this field.

We would also like to note that we provide direct observations of spermatozoa resisting internal flow due to reproductive tract contractions in Movie S3A, B as well as Movie S5B. We referred to these movies and pointed out the role of anchoring (sperm attachment) in preventing sperm from being squeezing out (LL 140-149, LL 224-241). Unfortunately, we cannot conceive of how this behaviour can be tested additionally in any uterus-resembling microfluidic device or ex-vivo systems. In line with your suggestion, we have rewritten the related result section and moved our related discussions in the result part to the discussion section (LL 224-241, LL 399-417).

The authors observed that large numbers of uterine sperm are attached to the entrance of the UTJ. Some sperm clustered and synchronized their flagellar beating. The authors speculated that this behavior served to push sperm in clusters onward through the UTJ.

We would like to note that we did not speculate that sperm clustering and their synchronization could serve to push spermatozoa in a cluster to move onward through the UTJ. We only pointed out our observation in recorded videos, that generative flow from the clustered spermatozoa pushed away other spermatozoa as seen in Movie S7 (LL 261-264). Although such sperm cooperation is possible (blocking passage of later sperm), we cannot draw that conclusion from our observation. The possibility you pointed out (pushing sperm onward through the UTJ) was suggested by Qu et al in 2021 [Cooperation-based sperm clusters mediate sperm oviduct entry and fertilization, Protein & Cell] based on their observations on cleared dead reproductive tracts.

The authors found only a few sperm trains in the uterus, UTJ, and oviduct, so they could not measure sufficient numbers of samples to test whether sperm trains swim faster than single sperm. Without sufficient data, they concluded that the "sperm trains did not move faster than unlinked single spermatozoa."

We would like to take this opportunity to clarify our claims. We do not claim that our current experiments can give the final verdict on whether the sperm train hypothesis for faster swimming is correct or not. The phrase “sperm trains did not move faster” was not intended to mean that the sperm train hypothesis is invalid. We did not draw a conclusion but dryly described the experimental data that we observed (LL 279-286). We would once again like to emphasize that the main claim of our manuscript is not to rule out the sperm train hypothesis, but to present the various dynamic interactions of the sperm head with the female reproductive tract. To make the statement more balanced, we revised the sentence as “observed sperm trains did not move faster or slower than unlinked single spermatozoa” (LL 281-282).

The authors hypothesized that the dense sperm clusters at the entrance into the UTJ could prevent the rival's sperm from entering the UTJ (due to plugging entrance and/or creating an outward flow to sweep back the rival's sperm), but they did not test it.

We agree that we were not able to test such possible function of the sperm cluster at UTJ entrance. Following your concerns, we revised the result part (LL 256-264) by removing most of our discussions related to the observed phenomena. We also integrated some interpretation rather to the discussion section (LL 421-437) and suggested that future works using appropriate microfluidic channel designs or sequential double mating experiments may be performed for additional tests (LL 443-447). However, we would like to point out that Movie S7C clearly shows surrounding sperms that are swept away from the sperm clusters. Since the sperm density is high, this is almost equivalent to a particle image velocimetry experiment, and we can clearly see the effect of the outward flow generated by the sperm clusters.