The viral context instructs the redundancy of costimulatory pathways in driving CD8+ T cell expansion

Figures

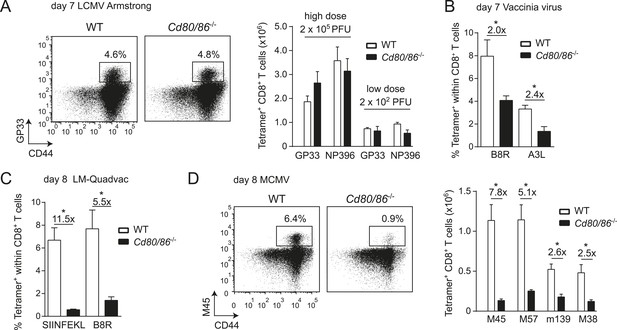

Differential requirements for CD28/B7-mediated costimulation in driving pathogen-specific CD8+ T cell expansion.

(A) Wild-type (WT) and Cd80/86−/− mice were infected with 2 × 102 (low dose) or 2 × 105 (high dose) PFU LCMV-Armstrong. The lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-specific CD8+ T cell response in the spleen was determined 7 days post-infection. Representative flow cytometric plots show CD3+/CD8+ cells that were stained with CD44 antibodies and MHC class I tetramers (high dose infection). Percentages indicate tetramer+ cells within the CD8+ T cell population. Bar graph shows total number of splenic LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells. (B) Mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU vaccinia virus (VV) WR and the percentage of tetramer+ cells within the CD8+ T cell population was determined in the blood 7 days post-infection. (C) The percentage of tetramer+ cells within the CD8+ T cell population was determined in the blood 7 days post-infection with 1 × 106 CFU LM-Quadvac. (D) Flow cytometric plots show a representative M45-specific tetramer staining of cells from WT and Cd80/86−/− mice at day 8 post-infection with 1 × 104 PFU mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV). Cells are gated on CD3+/CD8+ and the percentages indicate tetramer+ cells within the CD3+/CD8+ T cell population. Bar graph indicates the total number of splenic MCMV-specific CD8+ T cells. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 5–12 mice per group) of at least two independent experiments. Fold difference and significance (*p < 0.05) is indicated.

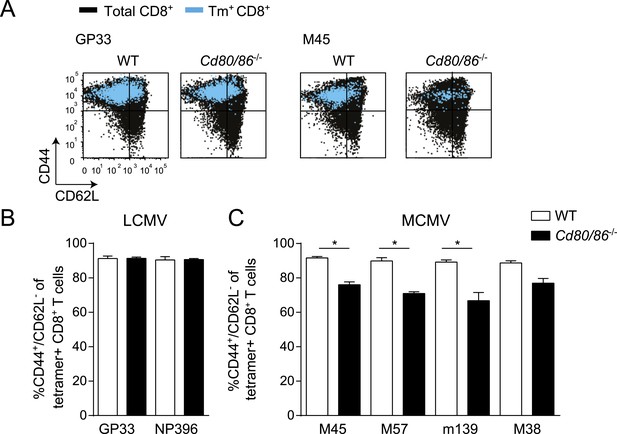

Costimulatory signals program effector cell differentiation of MCMV-specific but not of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells.

WT and Cd80/86−/− mice were infected with either 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong or 1 × 104 PFU MCMV-Smith. (A) Representative flow cytometric plots show cell surface expression of CD44 and CD62L on total CD8+ T cells (black) and on GP33 and M45-specific CD8+ T cells (blue) 7 days post LCMV and 8 days post MCMV infection. (B) Bar graph indicates the percentage of CD44+/CD62L− within the MHC class I tetramer+ population, 7 days post-LCMV infection. (C) The percentage of CD44+/CD62L− within the tetramer+ population was determined 8 days post MCMV infection. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 4–8 mice per group; *p < 0.05) of at least two independent experiments.

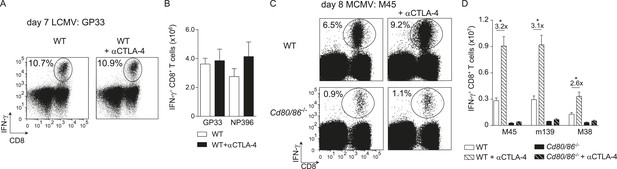

CTLA-4 blockade impacts B7-driven CD8+ T cell responses.

(A) CTLA-4 blocking antibodies were administrated during infection with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong in WT mice. At day 7 post-infection, the splenic LCMV-specific response was analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining. Representative flow cytometric plots show intracellular IFN-γ vs cell-surface CD8 staining after restimulation with GP33-41 peptide. The percentage of IFN-γ+ cells within the CD8+ T cell population is indicated. (B) Total numbers of splenic LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells are shown. (C) CTLA-4 interactions were abrogated by administration of blocking antibodies in WT and Cd80/86−/− mice upon infection with 1 × 104 PFU MCMV, and at day 8 post-infection the virus-specific response was analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining. Representative flow cytometric plots show intracellular IFN-γ vs CD8 staining after restimulation of splenocytes with M45985-993 peptide. The percentage of IFN-γ+ cells within the CD8+ T cell population is indicated. (D) Total numbers of MCMV-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen are shown. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 4–5 mice per group) of at least two independent experiments. Fold difference and significance (*p < 0.05) is indicated.

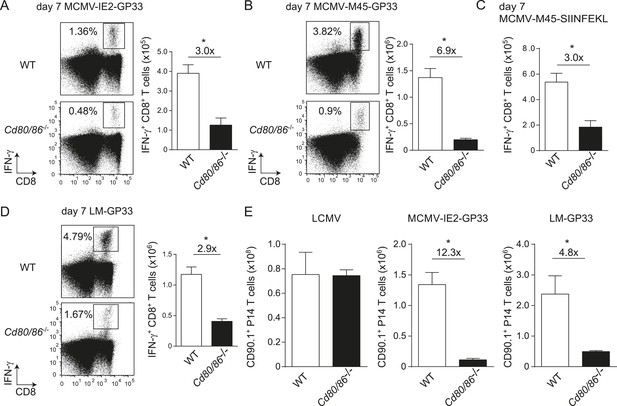

The context of viral epitope expression determines the requirements for B7-mediated costimulation in driving antigen-specific CD8+ T cell expansion.

(A, B) WT and Cd80/86−/− mice were infected with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33 or MCMV-M45-GP33, and 8 days post-infection the splenic GP33-specific CD8+ T cell response was determined by intracellular IFN-γ staining. Representative flow cytometric plots are shown and the percentage of IFN-γ+ cells within the CD8+ T cell population is indicated. Graphs indicate the total number of splenic GP33-specific CD8+ T cells. (C) The splenic SIINFKEL-specific CD8+ T cell response was determined by intracellular IFN-γ staining at day 8 post-infection with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-M45-SIINFEKL. (D) WT and Cd80/86−/− mice were infected with 1.5 × 103 CFU LM-GP33. At day 7 post-infection the splenic GP33-specific response was analyzed by intracellular IFN-γ staining upon restimulation with GP33 peptide. Representative flow cytometric plots are shown. The percentage of GP33-specific CD8+ T cells within the total CD8+ T cell population is indicated. Bar graph shows the total number of splenic GP33-specific CD8+ T cells. (E) 5 × 104 CD90.1+ Ifnar1+/+ P14 cells were adoptively transferred into WT and Cd80/86−/− mice that were subsequently infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong, 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33 or 1.5 × 103 CFU LM-GP33. At day 7 (LCMV, LM-GP33) or 8 (MCMV-IE2-GP33) post-infection, the magnitude of the P14 cell response in the spleen was determined. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 3–5 mice per group) of at least two independent experiments. Fold difference and significance (*p < 0.05) is indicated.

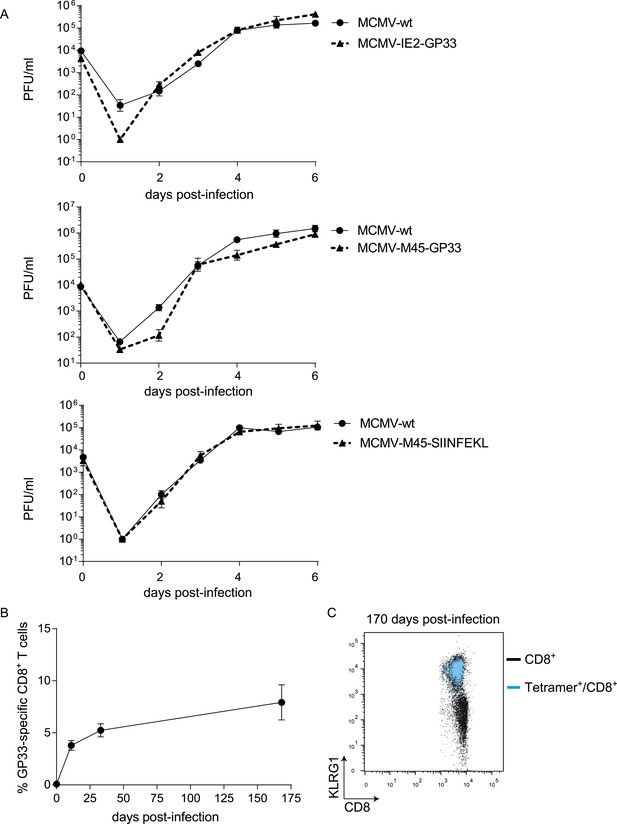

Characteristics of recombinant MCMVs.

(A) Replication kinetics of MCMV-IE2-GP33, MCMV-M45-GP33 and MCMV-M45-SIINFEKL on NIH 3T3 cells. Monolayers of 3T3 cells were infected with an MOI of 0.1. (B) WT mice were infected with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33 and the kinetics of the GP33-specific response was followed in the blood in time. (C) KLRG1 expression of total CD8+ T cells (black) and GP33+ CD8+ T cells (blue) is shown.

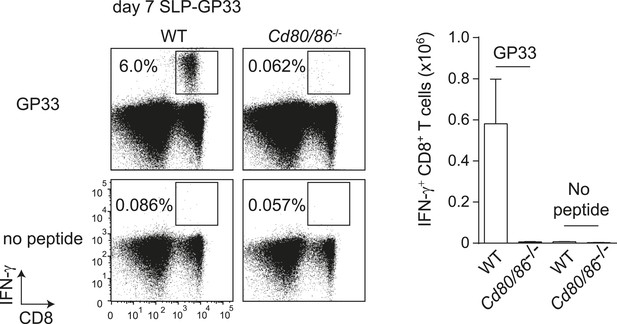

GP33-SLP vaccination is dependent on B7-mediated costimulation.

WT and Cd80/86−/− mice were vaccinated s.c. at the tail base with 75 µg synthetic long peptide (SLP) containing the LCMV-GP33 epitope combined with 20 µg CpG in PBS. The GP33-specific CD8+ T cell response in the spleen was determined 7 days post-vaccination by intracellular cytokine staining after in vitro restimulation with GP33-41 peptide. The percentage of GP33-specific CD8+ T cells within the total CD8+ T cell population is indicated. Graph shows the total number of splenic GP33-specific CD8+ T cells.

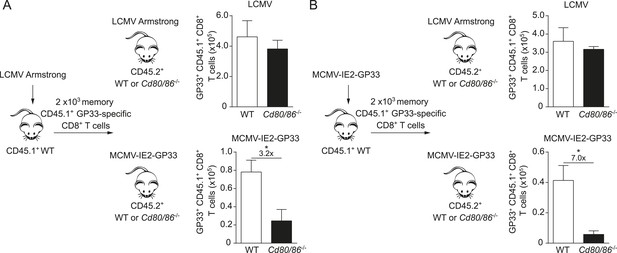

The infectious pathogen during antigenic re-challenge determines the requirements for CD28/B7-mediated costimulation for secondary expansion.

(A) Experimental setup: CD45.1+ WT mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong. After 4 months GP33-specific memory CD8+ T cells were sorted and 2 × 103 cells were adoptively transferred into CD45.2+ WT and Cd80/86−/− mice that were subsequently infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong or 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33. The total number of transferred GP33-specific CD8+ T cells was determined 6 days post re-challenge. (B) Similar experimental setup as described in (A), except CD45.1+ WT mice were infected with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 5 mice per group). Fold difference and significance (*p < 0.05) is indicated.

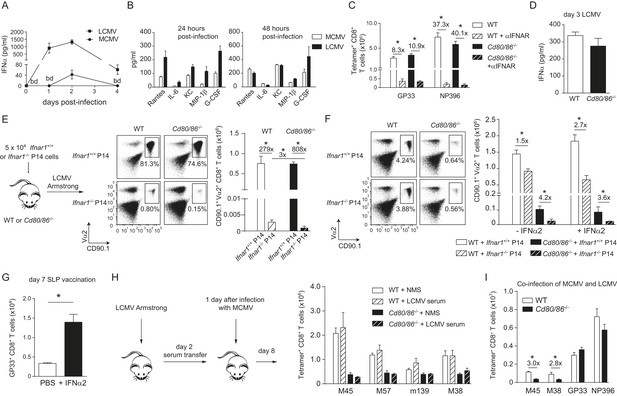

Influence of type I IFN signaling on the requirement of CD28/B7-mediated costimulation.

WT mice were infected with 1 × 104 PFU MCMV-Smith or 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong and at indicated times post-infection serum was collected. (A) Levels of IFNα in serum in time are shown (bd = below detection limit). (B) Concentrations of different pro-inflammatory cytokines as determined 24 and 48 hr post-infection. (C) Type I interferon receptor (IFNAR) blocking antibodies were administrated during LCMV infection in WT and Cd80/86−/− mice. The magnitude of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell response determined by MHC class I tetramer binding at day 7 post-infection is shown. Fold difference and significance (*p < 0.05) is indicated. (D) IFNα levels in serum are shown 3 days post LCMV infection. (E) Experimental setup: 5 × 104 CD90.1+ Ifnar1+/+ and Ifnar1−/− P14 cells were adoptively transferred in WT and Cd80/86−/− mice that were subsequently infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong. 7 days post-infection the total numbers of splenic P14 cells was determined. Representative flow cytometric plots show gated CD3+/CD8+ T cells stained for cell surface expression of CD90.1 and Vα2. Fold difference and statistical significance (*p < 0.05) between groups is indicated in the bar graphs. (F) Similar setup as in (E) except mice were infected with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33. In addition, on day 1 and 2, half of the mice received 1 × 105 units IFNα. 8 days post-infection the magnitude of the P14 cells in the spleen was determined. Representative flow cytometric plots show gated CD3+/CD8+ cells stained for cell surface expression of CD90.1 and Vα2. Bar graph shows total number of P14 cells in WT and Cd80/86−/− mice, and fold difference and statistical significance (*p < 0.05) between groups is indicated. (G) Mice were vaccinated with 75 µg SLP containing the GP33 epitope in PBS. 1 × 105 units IFNα was administrated after 18 and 48 hr. At day 7 post-vaccination, GP33-specific CD8+ T cell responses were analyzed. Significance between groups is indicated (*p < 0.05). (H) Experimental setup: WT mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong and 2 days post-infection serum was collected and transferred to mice that were infected 1 day prior with 1 × 104 PFU MCMV. The MCMV-specific CD8+ T cell response was determined 8 days post-infection by MHC class I tetramer binding. (I) WT and Cd80/86−/− mice were co-infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong and 1 × 104 PFU MCMV, and virus-specific responses were analyzed 7 days post-infection by MHC class I tetramer binding. Fold difference and significance (*p < 0.05) is indicated. Data in all bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 4–8 mice per group) of at least two independent experiments.

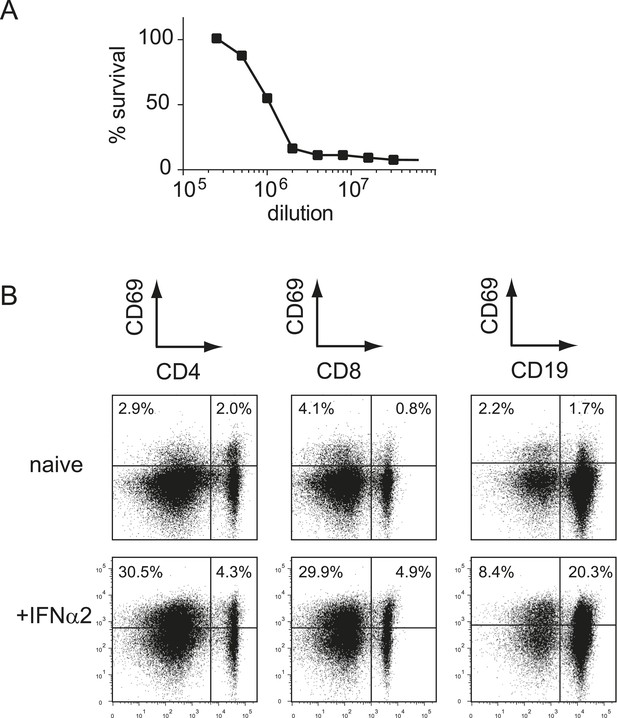

Recombinant type I IFN is functional in vitro and in vivo.

(A) L929 cells were pre-incubated with different concentrations of recombinant IFNα2 before addition of mengovirus. After 2 days of incubation, the survival of L929 cells was determined using the MTT assay. One unit was defined as the concentration at which 50% of the cells survived. (B) WT mice received 1 × 105 units of IFNα2 via i.p. injection. The expression of CD69 on splenic T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) and B cells (CD19+) was determined 18 hr after IFNα2 administration.

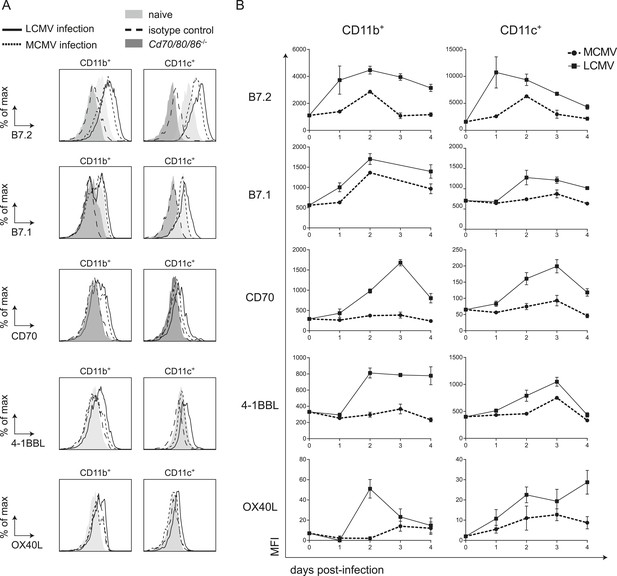

LCMV infection induces high expression of costimulatory ligands.

(A) Mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong or 1 × 104 PFU MCMV and costimulatory ligand expression was determined in the spleen. Histograms show cell surface expression of indicated costimulatory molecules on CD11b+ or CD11c+ cells at day 2 post-infection with either MCMV or LCMV. Representative staining of CD11b+ and CD11c+ cells from naive WT and Cd70/80/86−/− mice are depicted for comparison. Staining with an isotype control antibody is indicated as well. (B) Graphs depict mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of costimulatory ligand expression on CD11b+ or CD11c+ cells in time. For each sample the MFI of the corresponding isotype control was subtracted from the MFI for each costimulatory ligand. Graphs are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice per group) of at least two independent experiments.

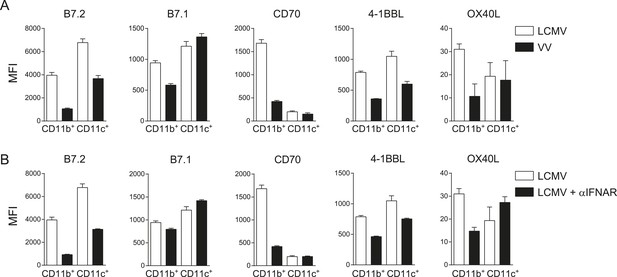

Costimulatory ligands are highly induced in LCMV infection.

(A) Mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong or 2 × 105 PFU VV-WR, and the expression of indicated costimulatory ligands was determined in the spleen on CD11b+ and CD11c+ cells 3 days post-infection. (B) IFNAR blocking antibodies were administrated during LCMV infection and the expression of indicated costimulatory ligands was determined in the spleen on CD11b+ and CD11c+ cells 3 days post-infection. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean +SEM (n = 4 mice per group).

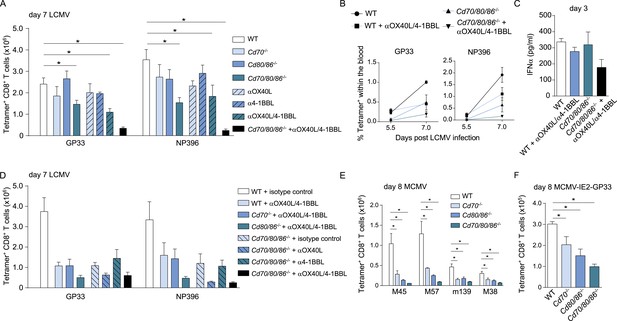

Redundant roles for costimulatory molecules in driving LCMV-specific CD8+ T cell expansion.

(A) WT and costimulation deficient (i.e., Cd70−/−, Cd80/86−/− and Cd70/80/86−/−) mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong. OX40L and/or 4-1BBL-mediated costimulation was abrogated by administration of blocking antibodies. The LCMV-specific CD8+ T cell response was determined 7 days post-infection using MHC class I tetramers. (B) The percentage of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the blood within the live gate at day 5.5 and day 7 post LCMV infection is shown as mean ± SEM. (C) IFNα levels in serum are shown 3 days post LCMV infection (n = 4 mice per group). (D) OX40L and/or 4-1BBL-mediated costimulation was abrogated by administration of blocking antibodies in WT and costimulation deficient mice that were subsequently infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV Armstrong. The LCMV-specific CD8+ T cell response was determined 7 days post-infection using MHC class I tetramers. All responses in mice receiving blocking antibodies to costimulatory molecules were significantly decreased (p < 0.05) compared to WT mice receiving isotype control antibodies. (E) The magnitude of splenic MCMV-specific CD8+ T cell pools determined by MHC class I tetramer staining after infection with 1 × 104 PFU MCMV-Smith is indicated. (F) The magnitude of the splenic GP33-specific CD8+ T cell response at day 8 post-infection with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33 is shown. All data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 5–12 mice per group of at least two independent experiments; *p < 0.05).

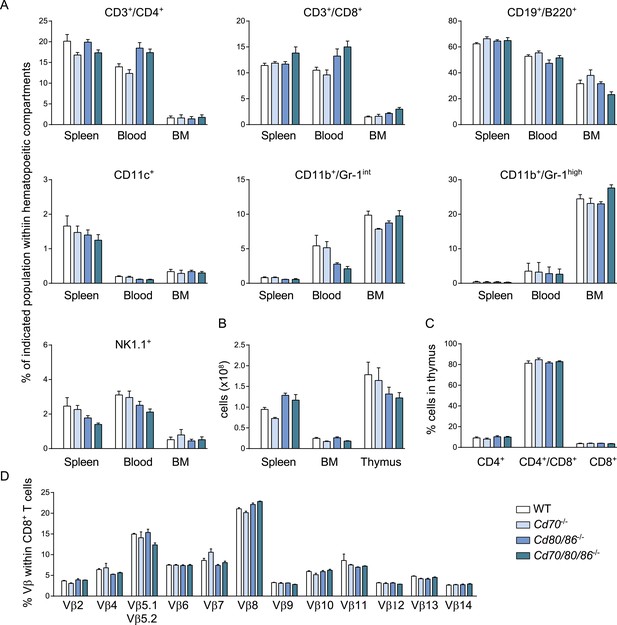

Cd70/80/86−/− mice have no defects in development of different hematopoietic populations.

(A) The percentage of different hematopoietic populations in naive WT, Cd70−/−, Cd80/86−/− and Cd70/80/86−/− mice in spleen, blood and bone marrow (BM) is shown. (B) The total number of cells in spleen, BM and thymus is indicated. (C) Percentages of thymocyte subsets are shown. (D) The percentage of different Vβ chains within the total CD8+ T cell pool in the spleen of naive WT and costimulation deficient mice is indicated. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 4–5 mice per group) of at least two independent experiments.

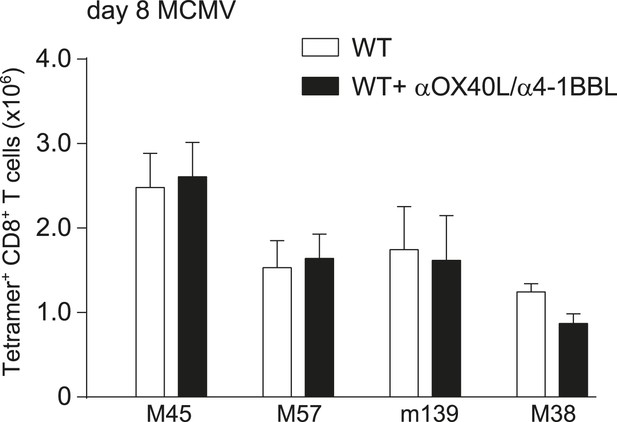

OX40L- and 4-1BBL-mediated costimulation is dispensable for primary expansion of MCMV-specific CD8+ T cells.

MCMV-specific CD8+ T cell responses were determined by MHC class I tetramer staining after infection with 1 × 104 PFU MCMV-Smith and upon dual blockade of OX40L and 4-1BBL interactions. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 4 mice per group).

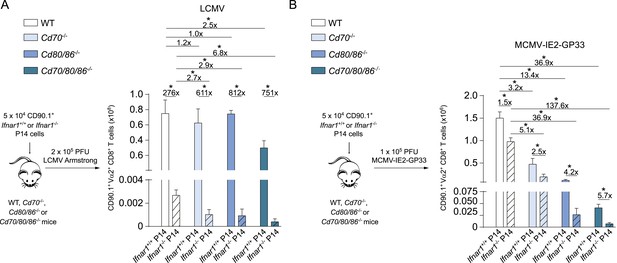

Type I IFN signaling in viral-specific CD8+ T cells is slightly redundant with costimulatory signals.

(A) Schematic of experimental setup: Ifnar1+/+ and Ifnar1−/− P14 cells were adoptively transferred in WT, Cd70−/−, Cd80/86−/− and Cd70/80/86−/− mice that were subsequently infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV. 7 days post-infection the total numbers of P14 cells was determined in the spleen. (B) Similar setup as in (A) except mice were infected with 1 × 105 PFU MCMV-IE2-GP33. 8 days post-infection the magnitude of the P14 cells was determined. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean + SEM (n = 4–8 mice per group) and representative of two independent experiments. The fold difference and significance (*p < 0.05) is indicated.