Electrostatics of salt-dependent reentrant phase behaviors highlights diverse roles of ATP in biomolecular condensates

eLife Assessment

In this important study, the authors employed three types of theoretical/computational models (coarse-grained molecular dynamics, analytical theory and field-theoretical simulations) to analyze the impact of salt on protein liquid-liquid phase separation. These different models reinforce each other and together provide convincing evidence to explain distinct salt effects on ATP mediated phase separation of different variants of caprin1. The insights and general approach are broadly applicable to the analysis of protein phase separation. Still, modeling at the coarse-grained level misses key effects that have been revealed by all-atom simulations, including salt-backbone coordination and strengthening of pi-type interactions by salt.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.100284.3.sa0Important: Findings that have theoretical or practical implications beyond a single subfield

- Landmark

- Fundamental

- Important

- Valuable

- Useful

Convincing: Appropriate and validated methodology in line with current state-of-the-art

- Exceptional

- Compelling

- Convincing

- Solid

- Incomplete

- Inadequate

During the peer-review process the editor and reviewers write an eLife Assessment that summarises the significance of the findings reported in the article (on a scale ranging from landmark to useful) and the strength of the evidence (on a scale ranging from exceptional to inadequate). Learn more about eLife Assessments

Abstract

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) involving intrinsically disordered protein regions (IDRs) is a major physical mechanism for biological membraneless compartmentalization. The multifaceted electrostatic effects in these biomolecular condensates are exemplified here by experimental and theoretical investigations of the different salt- and ATP-dependent LLPSs of an IDR of messenger RNA-regulating protein Caprin1 and its phosphorylated variant pY-Caprin1, exhibiting, for example, reentrant behaviors in some instances but not others. Experimental data are rationalized by physical modeling using analytical theory, molecular dynamics, and polymer field-theoretic simulations, indicating that interchain ion bridges enhance LLPS of polyelectrolytes such as Caprin1 and the high valency of ATP-magnesium is a significant factor for its colocalization with the condensed phases, as similar trends are observed for other IDRs. The electrostatic nature of these features complements ATP’s involvement in π-related interactions and as an amphiphilic hydrotrope, underscoring a general role of biomolecular condensates in modulating ion concentrations and its functional ramifications.

Introduction

Broad-based recent efforts have uncovered many intriguing features of biomolecular condensates, revealing and suggesting myriad known and potential biological functions (Shin and Brangwynne, 2017; Tsang et al., 2020; Lyon et al., 2021). These assemblies are underpinned substantially, though not exclusively, by liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) as well as folded domains of proteins and nucleic acids (Cinar et al., 2019; Bremer et al., 2022), while more complex equilibrium and non-equilibrium mechanisms also contribute (Harmon et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Kato and McKnight, 2018; Wurtz and Lee, 2018; McSwiggen et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2022; Mittag and Pappu, 2022; Shen et al., 2023; Pappu et al., 2023).

Electrostatics plays major roles in biophysical and biochemical processes (Honig and Nicholls, 1995; Zhou and Pang, 2018). Because of the relatively high compositions of charge residues in IDRs, electrostatics is particularly important for IDR LLPS (Nott et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016), which is often also facilitated by π-related interactions (Wang et al., 2018; Vernon et al., 2018), hydrophobicity, and hydrogen bonding (Murthy et al., 2019; Cai et al., 2022), and is modulated by temperature (Lin et al., 2018; Dignon et al., 2019a), hydrostatic pressure (Cinar et al., 2019; Cinar et al., 2020), osmolytes (Cinar et al., 2019), RNA (Maharana et al., 2018; Tsang et al., 2019; Dutagaci et al., 2021; Laghmach et al., 2022), salt, pH (Wang et al., 2017), molecular crowding (André and Spruijt, 2020; Patel et al., 2022; Kumari et al., 2024), and post-translational modifications (PTMs; Shin and Brangwynne, 2017; Kim et al., 2019; Owen and Shewmaker, 2019; Snead and Gladfelter, 2019). Multivalency underlies many aspects of IDR properties (Borg et al., 2007; Marsh et al., 2012; Song et al., 2013; Brangwynne et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2015). Here, we focus primarily on how PTM- and salt-modulated multivalent charge-charge interactions might alter IDR condensate behaviors and their possible functional ramifications. In general, electrostatic effects on IDR LLPS (Nott et al., 2015; Dutagaci et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021) are dependent upon their sequence charge patterns (Das and Pappu, 2013; Sawle and Ghosh, 2015; Lin et al., 2017b; Lin and Chan, 2017; Chang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2019a; Amin et al., 2020; Lyons et al., 2023; Pal et al., 2024a; Pal et al., 2024b). Intriguingly, some IDRs undergo reentrant phase separation (Cinar et al., 2019) or dissolution (Banerjee et al., 2017) when temperature, pressure (Cinar et al., 2019), salt (Krainer et al., 2021; Hong et al., 2022), RNA (Banerjee et al., 2017; Alshareedah et al., 2019), or concentrations of small molecules such as heparin (Babinchak et al., 2020) is varied. Reentrance, especially when induced by salt and RNA, suggest a subtle interplay between multivalent sequence-specific charge-charge interactions and hydrophobic, non-ionic (Krainer et al., 2021; Hong et al., 2022), cation-π (Banerjee et al., 2017; Alshareedah et al., 2019), or π-π interactions.

An important modulator of biomolecular LLPS is adenosine triphosphate (ATP). As energy currency, ATP hydrolysis is utilized to synthesize or break chemical bonds and drive transport to regulate ‘active liquid’ properties such as concentration gradients and droplet sizes (Wurtz and Lee, 2018; Bertrand and Lee, 2022). Examples include ATP-driven assembly of stress granules (Jain et al., 2016), splitting of bacterial biomolecular condensates (Guilhas et al., 2020), and destabilization of nucleolar aggregates (Hayes et al., 2018). ATP can also influence biomolecular LLPS without hydrolysis, akin to other LLPS promoters or suppressors (Nguemaha and Zhou, 2018; Ghosh et al., 2019) that are effectively ligands of the condensate scaffold (Ruff et al., 2021), or through ATP’s effect on lowering free [Mg2+] (Wright et al., 2019). Notably, as an amphiphilic hydrotrope (Martins et al., 2022) with intracellular concentrations much higher than that required for an energy source, ATP is also seen to afford an important function independent of hydrolysis by solubilizing proteins, preventing LLPS and destabilizing aggregates, as exemplified by measurements on several proteins including fused in sarcoma (FUS) (Patel et al., 2017).

Subsequent investigations indicate, however, that hydrolysis-independent [ATP] effects on biomolecular LLPS are neither invariably monotonic for a given system nor universal across different systems. For instance, ATP promotes, not suppresses, LLPS of an IgG1 antibody (Tian and Qian, 2021), basic IDPs (Kota et al., 2024), and enhances LLPS of full-length and the C-terminal domain (CTD) of FUS at low [ATP] but prevents LLPS at high [ATP] (Kang et al., 2018). The latter reentrant behavior has been surmised to arise from ATP binding bivalently (Kang et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2019) or trivalently (Ren et al., 2022) to charged residues arginine (R) or lysine (K) by a combination of cation-π and electrostatic interactions, an effect also seen in the ATP-mediated LLPS of basic IDPs (Kota et al., 2024). A similar scenario was invoked for the reentrant phase behavior of transactive response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43; Dang et al., 2021). Most recently, ATP-mediated assembly-disassembly reentrant behavior similar to that of FUS CTD was also observed for the RG/RRG-rich IDR motif with a positive net charge from the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein G (Zhu et al., 2024).

While π-related interactions are important for biomolecular LLPS in general (Wang et al., 2018; Vernon et al., 2018) and their interplay with electrostatics likely underlies reentrant biomolecular phase behaviors modulated by RNA (Banerjee et al., 2017; Alshareedah et al., 2019) or simple salts (Krainer et al., 2021), the degree to which electrostatics alone can, in large measure, rationalize hydrolysis-independent ATP-modulated biomolecular phase reentrance has not been sufficiently appreciated. This question deserves attention. For instance, the suppression of cold-inducible RNA-binding protein condensation by ATP has been suggested to be electrostatically driven (Zhou et al., 2021). The aforementioned ATP-modulated reentrant phase behavior of FUS (Kang et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2019) is reminiscent of the 236-residue N-terminal IDR of DEAD-box RNA helicase Ddx4’s lack of LLPS at low [NaCl] (<15–20 mM), LLPS at higher [NaCl] (Lin et al., 2020) and decreasing LLPS propensity when [NaCl] is further increased (Nott et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016). Indeed, the finding that FUS CTD (net charge per residue (NCPR) = 15/156 = 0.096) exhibits ATP-dependent reentrant phase behaviors while the N-terminal domain (NCPR = 3/267 = 0.011) does not (Kang et al., 2019) is consistent with electrostatics-based theory for the difference in salt-dependent LLPS of polyelectrolytes and polyampholytes (Lin et al., 2020) and a recent atomic simulation study of direct and indirect salt effects on LLPS (MacAinsh et al., 2024).

With this in mind, we seek to delineate the degree to which theories focusing primarily on electrostatics can rationalize experimental ATP-related LLPS data on the 103-residue C-terminal IDR of human cytoplasmic activation/proliferation-associated protein-1 (Caprin1). Full-length Caprin1 (709 amino acid residues) is a ubiquitously expressed phosphoprotein that regulates stress (Solomon et al., 2007; Towers et al., 2011; Vu et al., 2021; Song et al., 2022) and neuronal (El Fatimy et al., 2012) granules, is necessary for normal cellular proliferation (Ellis and Luzio, 1995; Wang et al., 2005), and may be essential for long-term memory (Nakayama et al., 2017). Caprin1 dysfunction leads to multiple diseases such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Yang et al., 2022) as well as language impairment and autism spectrum disorder (Pavinato et al., 2023), via, for example, Caprin1’s modulation of the function of the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP; Tsang et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019; El Fatimy et al., 2012). The C-terminal 607–709 Caprin1 IDR, referred to simply as Caprin1 below, is biophysically and functionally significant: It is sufficient for LLPS in vitro (Kim et al., 2019), important for assembling stress granules in the cell (Solomon et al., 2007; Towers et al., 2011), and has a substantial body of experiments (Kim et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021; Toyama et al., 2022) for comparison with theory. Since tyrosine phosphorylations of Caprin1 in vivo (Hornbeck et al., 2015) may regulate translation in neurons (Kim et al., 2019), the Caprin1 system is also useful for gaining insights into phosphoregulation of biomolecular condensates (Monahan et al., 2017; Dignon et al., 2018; Carlson et al., 2020).

Recent advances in theory and computation enable modeling of sequence-specific IDR LLPS (Lin et al., 2016; MacAinsh et al., 2024; Dignon et al., 2018; Rauscher and Pomès, 2017; Das et al., 2018b; Das et al., 2018c; McCarty et al., 2019; Danielsen et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019; Das et al., 2020; Hazra and Levy, 2020; Joseph et al., 2021). Among the approaches, polymer chain models of IDRs are inherently more realistic in capturing sequence properties than models without a chain description such as patchy particle theory (Nguemaha and Zhou, 2018). For chain models, all-atom simulation offers a high degree of geometric and energetic realism (Rauscher and Pomès, 2017) but its high computational cost often makes it difficult to achieve sufficient sampling and equilibration for the large system sizes that are needed for modeling biomolecular LLPS processes (MacAinsh et al., 2024). However, even coarse-grained explicit-chain simulation affords more realistic geometric and energetic representations than analytical theory, but analytical theory offers significant advantages in numerical tractability (Lin et al., 2023). For our present purposes, the analytical rG-RPA formulation (Lin et al., 2020), which synthesizes Kuhn-length renormalization (renormalized Gaussian, rG) and random phase approximation (RPA; Lin et al., 2016) to treat both high-net-charge polyelectrolytes and essentially net-neutral polyampholytes (Lin et al., 2020), is particularly well suited for Caprin1 and its phosphorylated variant pY-Caprin1. To gain deeper insights into the pertinent physical principles and to assess possible limitations of this analytical approximation, we further leverage a methodological combination of rG-RPA (Lin et al., 2020), field-theoretic simulation (FTS) (McCarty et al., 2019; Pal et al., 2021), and coarse-grained explicit-chain molecular dynamics (MD) (Dignon et al., 2018; Das et al., 2020) to better elucidate the effects of salt, phosphorylation, and ATP on LLPS of Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1.

Results

Overview of key observations from complementary approaches

The complementary nature of our multiple methodologies allows us to focus sharply on the electrostatic aspects of the hydrolysis-independent role of ATP in biomolecular condensation by comparing ATP’s effects with those of simple salt. Here, Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 are modeled minimally as heteropolymers of charged and neutral beads in rG-RPA and FTS. ATP and ATP-Mg are modeled as simple salts (single-bead ions) in rG-RPA, whereas they are modeled with more structural complexity as short charged polymers (multiple-bead chains) in FTS, although the latter models are still highly coarse-grained. Despite this modeling difference, rG-RPA and FTS both rationalize experimentally observed ATP- and NaCl-modulated reentrant LLPS of Caprin1 and a lack of a similar reentrance for pY-Caprin1 as well as a prominent colocalization of ATP with the Caprin1 condensate. Consistently, the same contrasting trends in the effect of NaCl on Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 are also seen in our coarse-grained MD simulations, although polymer field theories tend to overestimate LLPS propensity (Shen and Wang, 2017). The robustness of the theoretical trends across different modeling platforms underscores electrostatics as a significant component in the diverse roles of ATP in the context of its well-documented ability to modulate biomolecular LLPS via hydrophobic and π-related effects (Patel et al., 2017; Kota et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2019). Analyses of these other nonelectrostatic effects are mostly beyond the scope of the present work but their impact is nevertheless illustrated by the Flory-Huggins interactions augmented to rG-RPA to quantitatively account for experimental data and our MD simulation of the arginine-to-lysine Caprin1 mutants. These findings are detailed below.

Physical theories of Caprin1 and phosphorylated Caprin1 LLPSs as those of polyelectrolytes and polyampholytes

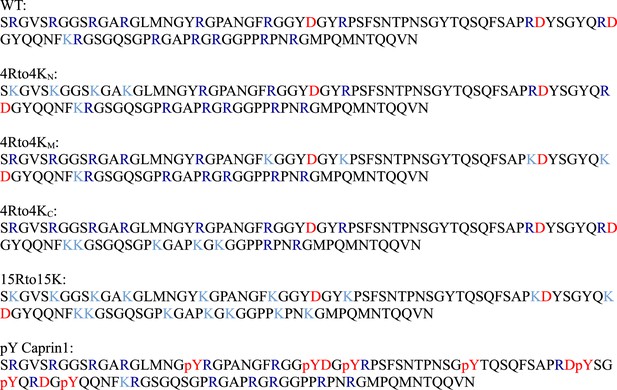

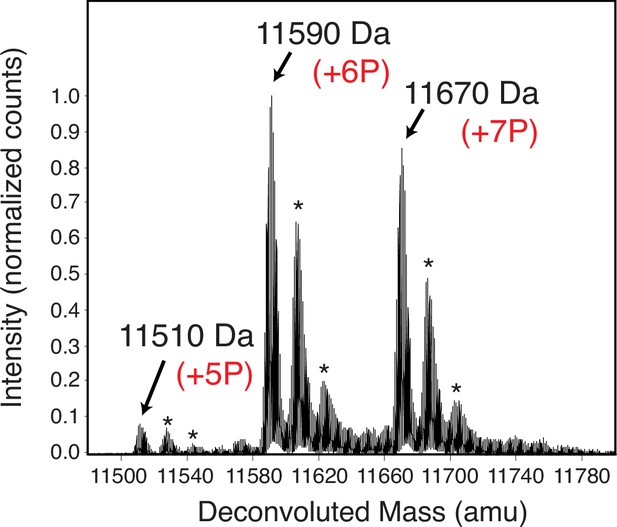

The 103-residue Caprin1 is a highly charged IDR with 19 charged residues [Figure 1a and Appendix 1, Appendix 1—figure 1]: 15 R, 1 K, and 3 aspartic acids (D); fraction of charged residues = 19/103 = 0.184 and NCPR = 13/103 = 0.126. With a substantial positive net charge, Caprin1’s phase behaviors are markedly different from those of polyampholytic IDRs with nearly zero net charge such as Ddx4 to which early sequence-specific LLPS theories were targeted (Nott et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2016). Instead, Caprin1 behaves like chemically synthesized polyelectrolytes (Dobrynin and Rubinstein, 2005). In contrast, when most or all of the 7 tyrosines (Y) in the Caprin1 IDR are phosphorylated (pY), negative charges are added to produce a near-net-neutral polyampholyte. Mass spectrometry indicates that the experimental sample of highly phosphorylated Caprin1 consists mainly of a mixture of IDRs with 6 or 7 phosphorylations (Appendix 1—figure 2). We refer to this experimental sample as pY-Caprin1 below. For simplicity, we use only the Caprin1 IDR with 7 pYs to model the behavior of this experimental sample in our theoretical/computational formulations, partly to avoid the combinatoric complexity of sequences with 5 or 6 pYs. Accordingly, since the charge of a pY is ≈ –2 at the experimental pH = 7.4, –14 charges are added to Caprin1 for our model pY-Caprin1, resulting in a polyampholyte with a very small NCPR = −1/103 = −0.00971 (Figure 1b). Both the experimental pY-Caprin1 (NCPR ≈ ±1/103 = ±0.00971) and model pY-Caprin1 are expected to exhibit phase properties similar to other polyampholytic IDRs.

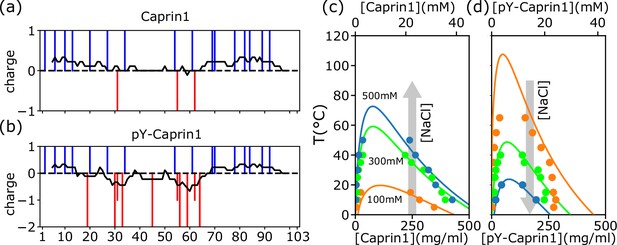

rG-RPA+FH theory predictions rationalize different salt dependence of Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 LLPS.

(a, b) Vertical lines indicate the sequence positions (horizontal variable) of positively charged residues (blue) and negatively charged residues or phosphorylated tyrosines (red) for (a) Caprin1 and (b) pY-Caprin1. (c, d) rG-RPA+FH coexistence curves (phase diagrams, continuous curves color-coded for the NaCl concentrations indicated) agree reasonably well with experiment (dots, same color code). The grey arrows in (c, d) highlight that when [NaCl] increases, LLPS propensity increases for (c) Caprin1 but decreases for (d) pY-Caprin1. As described in our prior RPA+FH and rG-RPA+FH formulations (Lin et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2020), the theoretical coexistence curves shown in (c, d) are determined by fitting an effective relative permittivity as well as the enthalpic and entropic parts of a FH parameter to experimental data. For the present Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 systems, the fitted , which is remarkably close to that of bulk water . The fitted is (1.0, 0.0) for Caprin1 and (1.0, −1.5) for pY-Caprin1. These fitted energetic parameters are equivalent (Lin et al., 2016) to and for forming a residue-residue contact in the Caprin1 system (c) (i.e., it is enthalpically favorable), and and for forming a residue-residue contact in the pY-Caprin1 system (d) (i.e., it is enthalpically favorable and entropically unfavorable).

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Experimental data points and numerical data for the theoretical curves in Figure 1c and d.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/100284/elife-100284-fig1-data1-v1.xlsx

While sequence-specific RPA has been applied successfully to model electrostatic effects on the LLPSs of various polyampholytic IDRs (Lin et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2016; Lin and Chan, 2017; Das et al., 2020; Wessén et al., 2021), RPA is less appropriate for polyelectrolytes with large NCPR (Mahdi and Olvera de la Cruz, 2000; Ermoshkin and Olvera de la Cruz, 2003; Orkoulas et al., 2003) because of its treatment of polymers as ideal Gaussian chains (Muthukumar, 2017). Traditionally, theories for polyelectrolytes tackle their peculiar conformations by various renormalized blob constructs (Dobrynin and Rubinstein, 2005; Mahdi and Olvera de la Cruz, 2000), two-loop polymer field theory (Muthukumar, 1996), modified thermodynamic perturbation theory (Budkov et al., 2015), and renormalized Gaussian fluctuation (RGF) theory (Shen and Wang, 2017; Shen and Wang, 2018), among others. As such, these formulations are mostly designed for homopolymers, making them difficult to apply directly to heteropolymeric biopolymers. In order to analyze Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 LLPSs, we utilize rG-RPA (Lin et al., 2020), which combines Gaussian chains of effective (renormalized) Kuhn length with the key idea of RGF (Sawle and Ghosh, 2015).

Phase properties predicted by rG-RPA theory for Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 with monovalent counterions and salt are in agreement with experiment

Figure 1c and d show that the salt- and temperature ()-dependent phase diagrams predicted by rG-RPA with an augmented Flory-Huggins (FH) mean-field parameter for nonelectrostatic interactions, where and are the enthalpic and entropic contributions, respectively, and is reduced temperature (Lin et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2020; Eq. 10 of Lin et al., 2016 and ‘rG-RPA+FH’ theory in Appendix 1), are in reasonable agreement with experiment using bulk [Caprin1] (initial overall concentration) ≈ 200µM. (Concentrations are provided in molarity and also as mass density in Figure 1 and subsequent figures.) The rG-RPA+FH results in Figure 1c indicate that (i) Caprin1 undergoes LLPS below 20 °C with 100 mM NaCl, and that (ii) LLPS propensity, quantified by the upper critical solution temperature (UCST), increases with [NaCl]. These predictions are consistent with experimental data, including the observation that Caprin1 does not phase separate at room temperature without salt, ATP, RNA, or other proteins, though Caprin1 LLPS can be triggered by adding wildtype (WT) and phosphorylated FMRP and/or RNA (overall [Caprin1] ≳ 10 μM) (Kim et al., 2019), NaCl (Wong et al., 2020), or ATP (overall [Caprin1] = 400 μM) (Kim et al., 2021). The trend here is also in line with other theories of polyelectrolytes (Shen and Wang, 2018). In contrast, rG-RPA+FH results in Figure 1d for pY-Caprin1 shows decreasing LLPS propensity with increasing [NaCl], consistent with experimental data and the expected salt dependence of LLPS of nearly net-neutral polyampholytic IDRs such as Ddx4 (Lin et al., 2016).

Interestingly, the decrease in some of the condensed-phase [pY-Caprin1]s with decreasing (orange and green symbols for ≲ 20 °C in Figure 1d trending toward slightly lower [pY-Caprin1]) may suggest a hydrophobicity-driven lower critical solution temperature (LCST)-like reduction of LLPS propensity as temperature approaches ∼ 0 °C as in cold denaturation of globular proteins (Lin et al., 2018; Dignon et al., 2019a), though the hypothetical LCST is below 0 °C and therefore not experimentally accessible. If that is the case, the LLPS region would resemble those with both an UCST and an LCST (Cinar et al., 2019). As far as simple modeling is concerned, such a feature may be captured by a FH model wherein interchain contacts are favored by entropy at intermediate to low temperatures and by enthalpy at high temperatures, thus entailing a heat capacity contribution in , with , (Lin et al., 2018; Dill et al., 1989; Kaya and Chan, 2003), beyond the temperature-independent and used in Figures 1c, d , 2. Alternatively, a reduction in overall condensed-phase concentration can also be caused by formation of heterogeneous locally organized structures with large voids at low temperatures even when interchain interactions are purely enthalpic (Figure 4 of Statt et al., 2020).

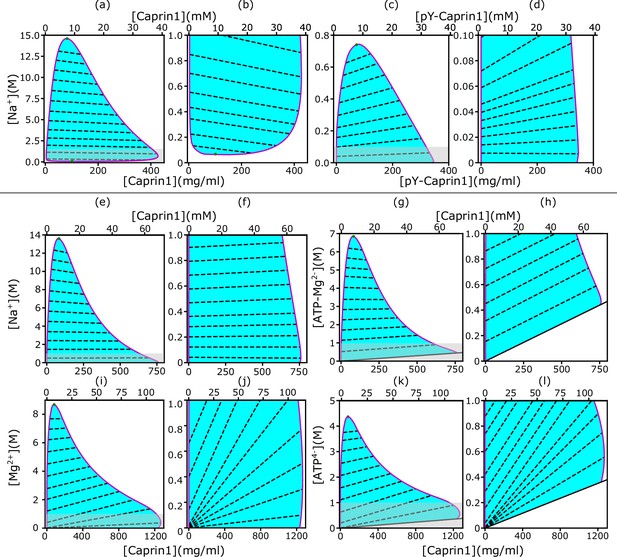

rG-RPA+FH theory rationalizes [NaCl]-modulated reentrant phase behavior of Caprin1.

In each salt-protein phase diagram ( K), tielines (dashed) connect coexisting phases on the boundary (magenta curve) of the cyan-shaded coexistence region. For clarity, zoomed-in views of the grey-shaded part in (a, c, e, g, i, k) are provided by the plots to the right, i.e., (b, d, f, h, j, l), respectively. The solid inclined lines in (g, h, k, l) mark the minimum counterion concentrations required for overall electric neutrality. Results are shown for monovalent cation and anion with Caprin1 (a, b) or pY-Caprin1 (c, d); or monovalent cation and divalent anion with Caprin1 (e–h); or divalent cation and tetravalent anion with Caprin1 (i–l). Cation-modulated reentrant phase behaviors is seen for a wide concentration range for Caprin1 in (a, b) but only a very narrow range of high Caprin1 concentrations in (e, f, i, j). The values for computing the phase diagrams here for Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1, respectively, are the same as those used for Figure 1c and d.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Numerical plotting data for the theory-predicted phase diagrams in Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/100284/elife-100284-fig2-data1-v1.xlsx

Salt-IDR two-dimensional phase diagrams are instrumental for exploring broader phase properties

Figure 1c and d, though informative, are computed by a restricted rG-RPA+FH that assumes a spatially uniform [Na+]. For a more comprehensive physical picture, we now examine possible differences in salt concentration between the IDR-dilute and condensed phases by applying unrestricted rG-RPA+FH to compute two-dimensional salt-Caprin1/pY-Caprin1 phase diagrams (Figure 2).

As stated in Materials and methods and Appendix 1, here we define ‘counterions’ and ‘salt ions’, respectively, as the small ions with charges opposite and identical in sign to that of the net charge, , of a given polymer. For the Caprin1/NaCl system, since Caprin1’s net charge is positive, Na+ is salt ion and Cl– is counterion. Overall electric neutrality of the system implies that the concentrations (’s) of polymer (), counterions (), and salt ions () are related by

where and are, respectively, the valencies of salt ions and counterions. For Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1, and –1, respectively, and are models for different small-ion species in the system. Specifically, in Figure 2, we identify the salt ion as Na+ (Figure 2a–f) and the counterion as Cl– (Figure 2a–d), the counterion as (ATP-Mg)2− (Figure 2g and h), the salt ion as Mg2+ and the counterion as ATP4− (Figure 2i–l). As mentioned above, in the present rG-RPA formulation, (ATP-Mg)2− and ATP4− are modeled minimally as a single-bead ion. They are represented by charged polymer models with more structural complexity in the FTS models below.

Behavioral trends of rG-RPA-predicted Na+-Caprin1 two-dimensional phase diagrams are consistent with experiment

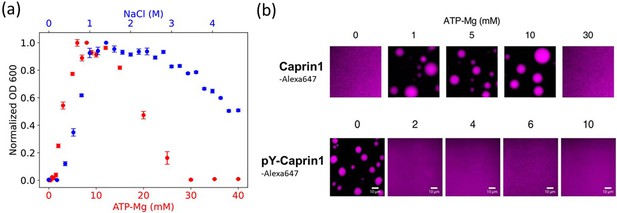

Notably, Figure 2a and b () predicts that Caprin1 does not phase separate without Na+, consistent with experiment, indicating that monovalent counterions alone (Cl– in this case) are insufficient for Caprin1 LLPS. When [Na+] is increased, the system starts to phase separate at a small [Na+] ≲ 0.1 M, with LLPS propensity increasing to a maximum at [Na+] ∼ 1 M before decreasing at higher [Na+], in agreement with experiment (Figure 3a, blue data points) and consistent with Caprin1 LLPS propensity increasing with [NaCl] from 0.1 to 0.5 M (Figure 1c). The predicted reentrant dissolution of Caprin1 condensate at high [Na+] in Figure 2a is consistent with measurement up to [Na+] ≈ 4.6 M indicating a significant decrease in LLPS propensity when [Na+] ≳ 2.5 M (Figure 3a), though the gradual decreasing trend suggests that complete dissolution of condensed droplets is not likely even when NaCl reaches its saturation concentration of ∼6 M.

Experimental demonstration of [ATP-Mg]- and [NaCl]-modulated reentrant phase behavior for Caprin1.

(a) Turbidity quantified by optical density at 600 nm (OD600, normalized by peak value) to assess Caprin1 LLPS propensity at [Caprin1]=200 μM [for ATP-Mg dependence (red), bottom scale] or [Caprin1]=300 μM [for NaCl dependence (blue), top scale], measured at room temperature (∼23 °C). Error bars are one standard deviations of triplicate measurements, which in most cases was smaller than the plotting symbols. The ATP-Mg dependence seen here for 200 μM Caprin1 is similar to the results for 400 μM Caprin1 (Figure 6C of Kim et al., 2021). (b) Microscopic images of Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 at varying [ATP-Mg] at room temperature, showing reentrant behavior for Caprin1 but not for pY-Caprin1. Each sample contains 200 μM of either Caprin1 or pY-Caprin1, with 1% of either Caprin1-Cy5 or pY-Caprin1-Cy5 (labeled with Cyanine 5 fluorescent dye) added for visualization, in a 25 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.4. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Numerical values of the experimental data plotted in Figure 3a.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/100284/elife-100284-fig3-data1-v1.xlsx

The negative tieline slopes in Figure 2a and b predict that Na+ is partially excluded from the Caprin1 condensate. This ‘salt partitioning’ is most likely caused by Caprin1’s net positive charge and is consistent with published research on polyelectrolytes with monovalent salt (Shen and Wang, 2018; Eisenberg and Mohan, 1959; Zhang et al., 2016). Here, the rG-RPA predicted trend is consistent with our experiment showing significantly reduced [Na+] in the Caprin1-condensed phase compared to the Caprin1-dilute phase (Table 1), although the larger experimental reduction of [Na+] in the Caprin1 condensed droplet relative to our theoretical prediction remains to be elucidated. In this regard, a similar experimental trend of Na+ tielines was observed recently for the IDP A1-LCD (WT) with a positive (+8) net charge (Posey et al., 2024). In contrast, for the near-neutral, very slightly negative model pY-Caprin1 (Figure 2c and d), rG-RPA predicts LLPS at [Na+] ≈ 0, and the positive tieline slopes indicate that [Na+] is higher in the condensed than in the dilute phase. Consistent with Figure 1d, Figure 2c shows that pY-Caprin1 LLPS propensity always decreases with increasing [Na+].

Sodium ions are depleted in the Caprin1-condensed phase relative to the Caprin1-dilute phase.

Consistent with theory, [Na+] is consistently lower in the Caprin1-condensed phase for two temperatures at which the measurements were performed.

| Bulk [Na+] (mM) | (°C) | Caprin1-Dilute [Na+] (mM) | Caprin1-Condensed [Na+] (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 25 | 341.3 ± 45.5 | 140.7 ± 6.0 |

| 300 | 35 | 289.5 ± 21.9 | 149.0 ± 2.5 |

-

uncertainty (±) is standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

rG-RPA-predicted salt-IDR two-dimensional phase diagrams underscore effects of counterion valency on LLPS

Interestingly, a different salt dependence of Caprin1 LLPS is predicted when the salt ion remains monovalent but the monovalent counterion Cl− is replaced by a divalent anion modeling (ATP-Mg)2– (as a single-bead ion) under the simplifying assumption that ATP4– and Mg2+ do not dissociate in solution. The corresponding rG-RPA results (Figure 2e–h) indicate that, in the presence of divalent counterions (needed for overall electric neutrality of the Caprin1 solution), Caprin1 can undergo LLPS without the monovalent salt (Na+) ions (LLPS regions extend to [Na+] = 0 in Figure 2e and f; that is, , in Equation 1), because the configurational entropic cost of concentrating counterions in the Caprin1 condensed phase is lesser for divalent () than for monovalent () counterions as only half of the former are needed for approximate electric neutrality in the condensed phase.

Other predicted differences between monovalent (Figure 2a and b) and divalent (Figure 2e and f) counterions’ impact on Caprin1 LLPS include: (i) The maximum condensed-phase [Caprin1] at low [Na+] is lower with monovalent than with divalent counterions ([Caprin1] ∼ 40 mM vs. ∼ 70 mM). (ii) The [Na+] at the commencement of reentrance (i.e., at the maximum condensed-phase [Caprin1]) is much higher with monovalent than with divalent counterions ([Na+] ∼ 1 M vs. ∼ 0.1 M). (iii) [Na+] is depleted in the Caprin1 condensate with both monovalent and divalent counterions when overall [Na+] is high (negative tieline slopes for [Na+] ≳ 2 M in Figure 2a and e). However, for lower overall [Na+], [Na+] is slightly higher in the Caprin1 condensate with divalent but not with monovalent counterions (slightly positive tieline slopes for [Na+] ≲ 2 M in Figure 2e and f). This prediction suggests that under physiological [Na+] = 150∼170 mM, monovalent positive salt ions such as Na+ can be attracted, somewhat counterintuitively, into biomolecular condensates scaffolded by positively charged polyelectrolytic IDRs in the presence of divalent counterions. This phenomenon most likely arises from the attraction of the positively charge monovalent salt ions to the negatively charged divalent counterions in the protein-condensed phase because although the three negatively charged D residues in Caprin1 can attract Na+, it is notable that Na+ is depleted in condensed Caprin1 when the counterion is monovalent (Figure 2a).

rG-RPA is consistent with experimental [ATP-Mg]-dependent Caprin1 reentrant phase behaviors

For the , case in Figure 2i–l modeling (ATP-Mg)2− complex dissociating completely in solution into Mg2+ salt ions and ATP4− counterions (modeled as single-bead ions), rG-RPA predicts Caprin1 LLPS with ATP4− (Figure 2k and l) in the absence of Mg2+ (the LLPS region includes the horizontal axes in Figure 2i and j), likely because the configurational entropy loss of tetravalent counterions in the Caprin1 condensate is less than that of divalent and monovalent counterions. Tetravalent counterions also increase the theoretical maximum condensed-phase [Caprin1] to ≳ 120 mM. At the commencement of reentrance (maximum condensed-phase [Caprin1] in Figure 2i and j), [Mg2+] ∼ 0.4 M, which is intermediate between the corresponding [Na+] ∼ 1.0 and 0.1 M, respectively, for monovalent and divalent counterions with and (1, 1). All tieline slopes for Mg2+ and ATP4− in Figure 2i–l are significantly positive, except in an extremely high-salt region with [Mg2+] > 8 M, indicating that [(ATP-Mg)2−] is almost always substantially enhanced in the Caprin1 condensate. These observations from analytical theory will be corroborated by FTS below with the introduction of structurally more realistic models of (ATP-Mg)2−, ATP4− together with the possibility of simultaneous inclusion of Na+, Cl−, and Mg2+ in the FTS models of Caprin1/pY-Caprin1 LLPS systems. Despite the tendency for polymer field theories to overestimate LLPS propensity and condensed-phase concentrations quantitatively because they do not account for ion condensation (Shen and Wang, 2017)—which can be severe for small ions with more than ±1 charge valencies as in the case of condensed [Caprin1] ≳ 120 mM in Figure 2i–l, our present rG-RPA-predicted semi-quantitative trends are consistent with experiments indicating [ATP-Mg]-dependent reentrant phase behavior of Caprin1 (Figure 3a, red data points, and Figure 3b) and that [Mg2+] as well as [ATP4−] are significantly enhanced in the Caprin1 condensate by a factor of ∼5–60 for overall [ATP-Mg] = 3–30 mM (Table 2).

Colocalization of ATP-Mg in the Caprin1-condensed phase.

For three overall ATP-Mg concentrations at room temperature, the concentrations of ATP4− and Mg2+ are all significantly higher in the Caprin1-condensed than in the Caprin1-dilute phase.

| Caprin1-Dilute | Caprin1-Condensed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ATP-Mg] (mM) | [Caprin1] (μM) | [Mg2+] (mM) | [ATP4−] (mM) | [Caprin1] (mM) | [Mg2+] (mM) | [ATP4−] (mM) |

| 3 | 67.7±5.0 | 2.85±0.05 | 2.76±0.07 | 29.9±3.8 | 70.7±6.0 | 143±30 |

| 10 | 26.4±1.2 | 8.57±0.14 | 8.53±0.97 | 35.3±3.5 | 137±12 | 197±11 |

| 30 | 117±3 | 28.2±0.3 | 27.6±0.8 | 28.0±2.0 | 134±7 | 174±22 |

Coarse-grained MD with explicit small ions is useful for investigating subtle salt dependence in biomolecular LLPS

To gain deeper insights, we extend the widely-utilized coarse-grained explicit-chain MD model for biomolecular condensates (Dignon et al., 2018; Das et al., 2020; Silmore et al., 2017) to include explicit small cations and anions (Materials and methods). ATP-mediated LLPS of short basic peptides was studied recently using all-atom simulations indicating ATP engaging in electrostatic and cation-π bridging interactions (Kota et al., 2024). Here, we limit the small ions in our coarse-grained MD simulations of Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 LLPS to Na+ and Cl–, focusing on the physical origins of reentrance or lack thereof as well as the effects of ariginine-to-lysine (RtoK) mutations on Caprin1. Coarse-grained models allow for the study of larger systems (IDPs of longer chain lengths and more IDPs in the system), though they cannot provide insights into more subtle structural and energetic effects as in all-atom simulations (Kota et al., 2024; Krainer et al., 2021; MacAinsh et al., 2024). For computational efficiency, here we neglect solvation effects that can arise from the directional hydrogen bonds among water molecules (see, e.g., Shimizu and Chan, 2001) by treating other aspects of the aqueous solvent implicitly as in most, although not all (Lin et al., 2023; Wessén et al., 2021) applications of the methodology (Dignon et al., 2018). Several coarse-grained interaction schemes were used in recent MD simulations of biomolecular LLPS (Dignon et al., 2018; Das et al., 2020; Joseph et al., 2021; Regy et al., 2021; Dannenhoffer-Lafage and Best, 2021; Tesei et al., 2021; Wessén et al., 2022a; Wessén et al., 2023; Dignon et al., 2019b). Since we are primarily interested in general principles rather than quantitative details of the phase behaviors of Caprin1 and its RtoK mutants, here we adopt the Kim-Hummer (KH) energies for pairwise amino acid interactions derived from contact statistics of folded protein structures (Dignon et al., 2018), which can largely capture the experimental effects of R vs K on LLPS (Das et al., 2020).

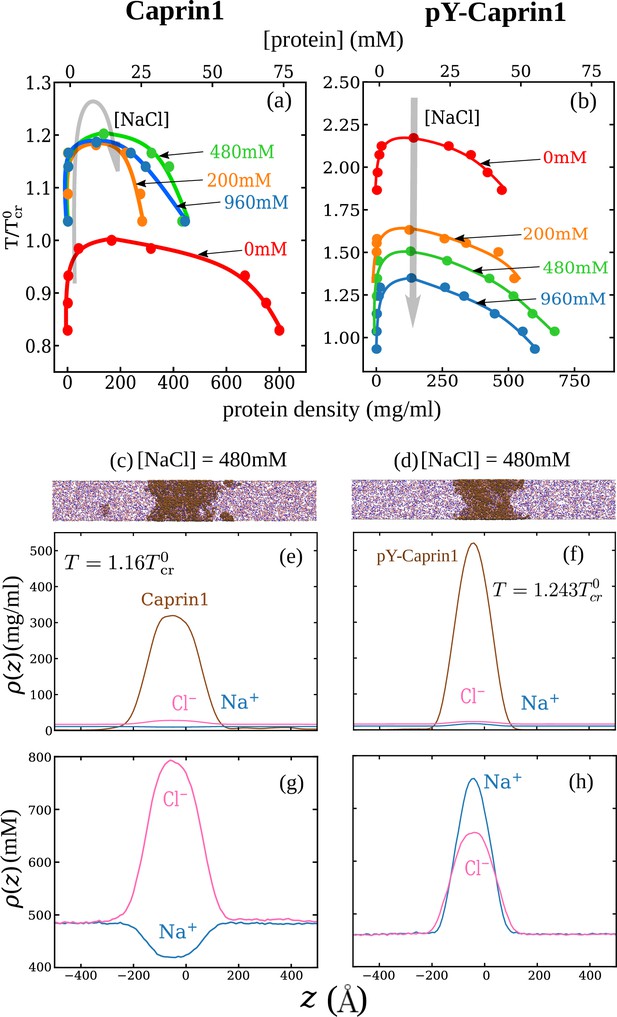

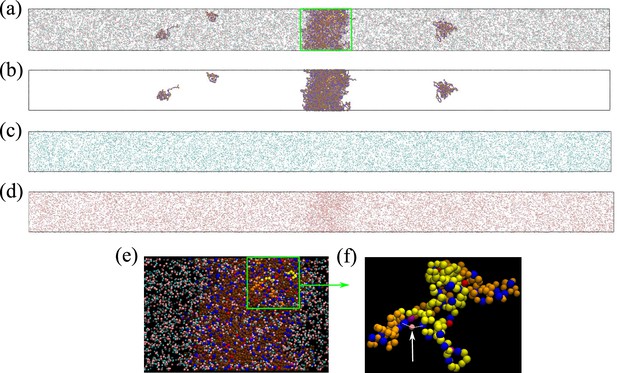

Explicit-ion MD rationalizes experimentally observed [NaCl]-dependent Caprin1 reentrant phase behaviors and depletion of Na+ in Caprin1 condensate

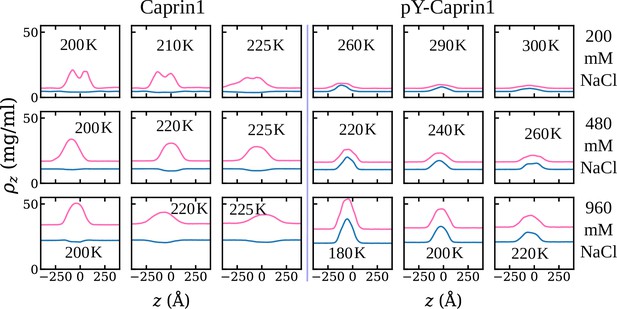

Consistent with experiment (Figure 3) and rG-RPA (Figure 2a–d), explicit-ion coarse-grained MD results in Figure 4 show [NaCl]-dependent reentrant phase behavior for Caprin1 but not for pY-Caprin1 (non-monotonic and monotonic trends indicated, respectively, by the grey arrows in Figure 4a and b). In other words, the critical temperature , which is defined as the maximum temperature (UCST) of a given phase diagram (binodal, or coexistence curve), increases then decreases with addition of NaCl for Caprin1 but always decreases with increasing [NaCl] for pY-Caprin1. Moreover, consistent with the rG-RPA-predicted tielines in Figure 2a–d (negative slopes for Caprin1 and positive slopes for pY-Caprin1), Figure 4e and g show that Na+ is slightly depleted in the Caprin1 condensed droplet, exhibiting the same trend as that in experiment (Figure 3a, blue data points; and Table 1) but is enhanced in the pY-Caprin1 droplet (Figure 4f and h). Because model temperatures in Figure 4a and b and subsequent MD results are given in units of the MD-simulated of WT Caprin1 at [NaCl] = 0 (denoted as here), the ’s of systems with higher or lower LLPS propensities than WT Caprin1 at zero [NaCl] is characterized, respectively, by or < 1.

Explicit-ion coarse-grained MD rationalizes [NaCl]-modulated reentrant behavior for Caprin1 and lack thereof for pY-Caprin1.

(a) Simulated phase diagrams (binodal curves) of Caprin1 at different temperatures plotted in units of (see text). Symbols are simulated data points. Continuous curves are guides for the eye. Grey arrow indicates variation in [NaCl]. (b) Same as (a) but for pY-Caprin1. (c) A snapshot showing phase equilibrium between dilute and condensed phases of Caprin1 (brown chains) immersed in Na+ (blue) and Cl– (red) ions simulated at [NaCl]=480 mM. (d) A similar snapshot for pY-Caprin1. (e, f) Mass density profiles, (in units of mg/ml), of Na+, Cl–, and (e) Caprin1 or (f) pY-Caprin1 along the elongated dimension of the simulation box showing variations of Na+ and Cl– concentrations between the protein-dilute phase (low for protein) and protein-condensed phase (high ρ for protein) at the simulation temperatures indicated. (g, h) Corresponding zoomed-in concentration profiles in units of mM for Na+ and Cl–. Additional mass density profiles for [NaCl]=200 mM and 400 mM are provided in Appendix 1—figure 3.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Numerical plotting data for the coarse-grained molecular dynamics-simulated curves in Figure 4.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/100284/elife-100284-fig4-data1-v1.xlsx

Figure 4e and g show that [Cl–] is enhanced while [Na+] is depleted in the Caprin1 droplet. By comparison, Figure 4f and h show that both [Cl–] and [Na+] are enhanced in the pY-Caprin1 droplet with an excess of [Na+] to balance the negatively charged pY-Caprin1 (Figure 4h). The enhancement of [Cl–] in the Caprin1 condensed phase depicted in Figure 4f and h is further illustrated in Figure 5a–d by comparing the entire simulation box with a condensed droplet in the middle (Figure 5a) with individual distributions of the Caprin1 IDR (Figure 5b), Na+ (Figure 5c), and Cl− (Figure 5d). A similar trend, also attributed to charge effects, was observed in explicit-water, explicit-ion MD simulations in the presence of a preformed condensate of the N-terminal RGG domain of LAF-1 with a positive net charge (Zheng et al., 2020). For Caprin1, Figure 5e and f suggests that, as counterion, Cl– can coordinate two positively charged R residues and thereby stabilize indirect counterion-bridged interchain contacts among polycationic Caprin1 molecules to promote LLPS, consistent with an early lattice-model analysis of generic polyelectrolytes (Orkoulas et al., 2003) and a recent atomic simulation study of A1-LCD (MacAinsh et al., 2024).

Counterions can stabilize Caprin1 condensed phase by favorable bridging interactions.

(a) Snapshot from explicit-ion coarse-grained MD under LLPS conditions for Caprin1, showing the spatial distributions of Caprin1, Na+, and Cl– (as in Figure 4c). The three components of the same snapshot are also shown separately in (b) Caprin1, (c) Na+, and (d) Cl–. (e) A zoomed-in view of the condensed droplet corresponding to the green box in (a), now with a black background and a different color scheme. (f) A further zoomed-in view of the part enclosed by the green box in (e) focusing on two interacting Caprin1 chains. A Cl– ion (pink bead indicated by the arrow) is seen interacting favorably with two arginine residues (blue beads) on the two Caprin1 chains (whose uncharged residues are colored differently by yellow or orange, lysine and aspartic acids in both chains are depicted, respectively, in magenta and red).

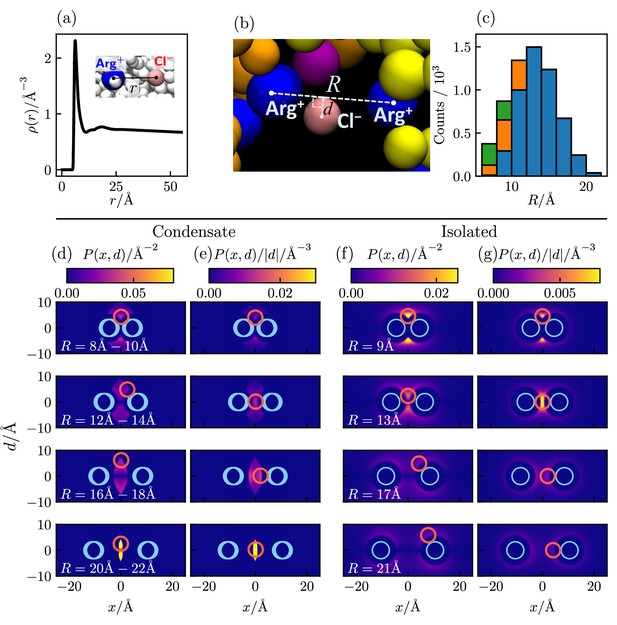

Explicit-ion MD offers insights into counterion-mediated interchain bridging interactions among condensed Caprin1 molecules

To assess the extent to which Cl–-mediated bridging interactions (as illustrated in Figure 5f) contribute to condensation of polyelectrolytic IDRs, we examine the relative positions of positively charged arginine residues (Arg+) and negatively charged counterions (Cl–) of a Caprin1 solution under phase-separation conditions in which essentially all Caprin1 molecules are in the condensed phase, using 4000 frames (MD snapshots) of an equilibrated salt-free ([NaCl] = 0) ensemble of 100 WT Caprin1 chains (net charge per chain = +13) with 1300 Cl– counterions at as an example (Figure 6). For simplicity, we focus on Arg+–Cl– interactions because the overwhelming majority (15/16) of the positively charged residues in Caprin1 are arginines. The computed radial distribution function, , of Cl– around a given Arg+ exhibits a sharp peak at small that drops to a minium at Å (Figure 6a), indicating a strong spatial association between the oppositely charged Arg+ and Cl– as expected. Indeed, within the ensemble we analyze, 5,121,148/(4000×1300) = 98.5% of the Cl– ions are within 11 Å of an Arg+. We next enumerate putative bridging interactions involving two Arg+s on different Caprin1 chains and one Cl– (Figure 6b) by identifying three-bead configurations in which the distance of Cl– to each of the two Arg+ is ≤ 11 Å (within the dominant small-r peak of in Figure 6a), which implies that the distance between the two Arg+s is ≤ 22 Å. In our ensemble, 4,519,387/(4000×1300) = 86.9% of the Cl– counterions are identified to be in one or more of a total of 25,112,331 such putative bridging interaction configurations. This means that, on average, each Cl– is involved in 25,112,331/4,519,387 = 5.56 configurations, and thus are coordinating ≈ 4 Arg+s because there are 6 (≈5.56) ways of pairing 4 Arg+s. Figure 6c shows the distribution of putative bridging configurations with respect to Arg+–Arg+ distance . Spatial distributions of Cl– in these configurations are provided in Figure 6d and e, which are quite similiar to those of isolated Arg+–Cl––Arg+ systems for Å (Figure 6f and g). Among the putative bridging configurations, we make an energetic distinction between true bridging and neutralizing (screening) configurations. Physically, a true bridging configuration may be defined by an overall favorable (< 0) sum of (i) unfavorable Coulomb potential between two Arg+ and (ii) the favorable Coulomb potential between the Cl– and one of the Arg+s that is farther away from the Cl–. By the same token, a neutralizing (screening) configuration may be defined by a corresponding overall unfavorable or neutral (≥ 0) sum of these two Coulomb potentials (i.e., the farther Arg+–Cl– distance is larger than the Arg+–Arg+ distance). In this regard, and in more general terms, Cl– ions in bridging and neutralizing interactions may be considered, respectively, as a ‘strong-attraction promoter’ and a ‘weak-attraction suppressor’ of LLPS (Nguemaha and Zhou, 2018; Ghosh et al., 2019).

Counterion interactions in polyelectrolytic Caprin1.

Shown distributions are averaged from 4000 equilibrated coarse-grained MD snapshots of 100 Caprin1 chains and 1300 Cl– counterions under phase-separation conditions () in a 115×115×1610 Å3 simulation box in which essentially all Caprin1 chains are in a condensed droplet. (a) Radial distribution function of Cl– around a positively charged arginine residue (Arg+). (b) A zoomed-in view of Figure 5f showcasing a putative bridging configuration with a Cl– interacting favorably with a pair of Arg+s on two different Caprin1 chains. Configurational geometry is characterized by Arg+--Arg+ distance and the distance of the Cl– from the line connecting the two Arg+s. (c) Distribution of putative bridging interaction configurations with respect to . Numbers of true bridging, neutralizing, and intermediate configurations are, respectively, in blue, green and orange. (d, e) Heat maps of two-dimensional projections of spatial distributions of Cl– around two Arg+s satisfying the putative bridging interaction conditions among the MD snapshots. (f, g) Corresponding projected distributions of isolated Arg+--Cl–--Arg+ Boltzmann-averaged systems at model temperature . Here, is the total density of Cl– on a circle of radius perpendicular to the heat map at horizontal position (d, f); thus the average Cl– density at a given point is , the patterns of which are exhibited by heat maps in (e, g). is symmetric with respect to by construction, i.e., . In each heat map, the size and (ranges of) positions of model Arg+s are indicated by blue circles; the size and the position or one of two positions (at ±d) of maximum Cl– density is indicated by a magenta circle. The MD-simulated distributions of the condensed system (d, e) are quite similar to the theory-computed isolated system (f, g) for Å, indicating that individual bridging interactions in the crowded Caprin1 condensates may be understood approximately by the electrostatics of an isolated, three-bead Arg+--Cl–--Arg+ system. For larger , the heat maps in (f, g) and (d, e) are not as similar because some of the configurations in the isolated system (f, g) are precluded by the requirement that Arg+--Cl– distance < 11 Å for putative bridging interactions in (d, e).

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Numerical values of the coarse-grained molecular dynamics-simulated data plotted in Figure 6a and c.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/100284/elife-100284-fig6-data1-v1.xlsx

In the present analysis, we group putative bridging configurations by in bins of 2 Å (Figure 6c). Accordingly, we may classify Cl– positions satisfying the above condition of favorable (< 0) sum of Coulomb potentials for all values within the 2 Å range of the bin as in true bridging configurations (79.6%), those Cl– positions satisfying the above condition of unfavorable (≥ 0) sum of Coulomb potentials for all values in the 2 Å range as in neutralizing configurations (7.4%), and those that satisfy neither as ‘intermediate’ configurations (13.0%). Even with this more stringent criterion, ≈80% of putative bridging configurations are true bridging configurations. Because on average a Cl– counterion known to be involved in at least one putative bridging configuration is on average participating in ∼ 5–6 such configurations, the probability that it is involved in at least one true bridging configuration is very high, at ≈ 1.0 − (0.2)5 = 99.97%. Thus, even without taking into consideration bridging interactions involving lysines, we may reasonably conclude that an overwhelming majority (≈ 87%) of Cl− counterions in the coarse-grained MD system considered are engaged in condensation-driving true bridging interactions coordinating pairs of Arg+ on different Caprin1 chains. Similar extensive Cl− and Na+ bridging interactions are observed in a recent all-atom molecular dynamics study of LLPS of short peptides under a variety of overall salt concentrations (MacAinsh et al., 2024).

Explicit-ion MD rationalizes [NaCl]-dependent phase properties of arginine-lysine mutants of Caprin1

We apply our MD methodology also to four RtoK Caprin1 variants, termed 15Rto15K, 4Rto4KN, 4Rto4KM, and 4Rto4KC (Appendix 1—figure 1), which involve 15 or 4 RtoK substitutions (Wong et al., 2020). The simulated phase diagrams in Figure 7 exhibit reentrant phase behaviors for all three 4Rto4K variants. While these results are consistent with experiments showing LLPS of these 4Rto4K variants commencing at different nonzero [NaCl]s (Wong et al., 2020), the simulated reentrant dissolution is not observed experimentally, probably because the actual [NaCl] needed is beyond the experimentally investigated or physically possible range of salt concentration. Simulated reentrant phase behaviors are also seen for 15Rto15K; but as will be explained below, its much lower simulated UCST is consistent with no experimental LLPS for this variant (Wong et al., 2020). Since our main focus here is on general physical principles, we do not attempt to fine-tune the MD parameters for a quantitative match between simulation and experiment. Experimentally, only WT exhibits a clear trend toward reentrant dissolution of condensed droplets (with a LLPS propensity plateau at [NaCl] ≈ 1.55−2.5 M, Figure 3a, blue data points), whereas the LLPS of 4Rto4KM and 4Rto4KC commences at [NaCl] ≈ 1.3 M, LLPS propensity then increases with [NaCl] (a trend consistent with the MD-predicted increasing LLPS propensity at low [NaCl]s in Figure 7b and c), but no sign of reentrant dissolution is seen up to the maximum [NaCl] = 2 M investigated experimentally for the RtoK variants (Figure 9B of Wong et al., 2020). In contrast, the MD phase diagrams in Figure 7 show a maximum LLPS propensity (highest ) at [NaCl] ≈ 0.5 M. This qualitative agreement with quantitative mismatch suggests that real Caprin1 LLPS is somewhat less sensitive to small monovalent ions than that stipulated by the present MD model. This question should be tackled in future studies by considering, for example, alternate pairwise amino acid interaction energies (Das et al., 2020; Dignon et al., 2018; Joseph et al., 2021; Regy et al., 2021; Dannenhoffer-Lafage and Best, 2021; Tesei et al., 2021; Wessén et al., 2022a; Wessén et al., 2023) and their temperature dependence (Cinar et al., 2019; Dignon et al., 2019a).

Explicit-ion coarse-grained MD rationalizes [NaCl]-modulated phase behavior for RtoK variants of Caprin1.

Four variants studied experimentally (Wong et al., 2020) are simulated: (a) 15Rto15K, in which 15 R’s in the WT Caprin1 IDR are substituted by K, (b) 4Rto4KN, (c) 4Rto4KM, and (d) 4Rto4KC, in which 4 R’s are substituted by K in the (b) N-terminal, (c) middle, and (d) C-terminal regions, respectively. Top panels show positions of the R (dark blue) and K (cyan) along the Caprin1 IDR sequence. Lower panels are phase diagrams in the same style as Figure 4. The phase diagrams for WT Caprin1 from Figure 4a are included as continuous curves with no data points in (a) for comparison.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

Numerical values of the coarse-grained molecular dynamics-simulated data points plotted as filled circles in the phase diagrams in Figure 7.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/100284/elife-100284-fig7-data1-v1.xlsx

Limitations notwithstanding, the MD-simulated trend agrees largely with experiment. Predicted LLPS propensities quantified by the in Figure 7 follow the rank order of WT > 4Rto4KM > 4Rto4KN ≈ 4Rto4KC > 15Rto15K, which is essentially identical to that measured experimentally, viz., WT > 4Rto4KM > 4Rto4KC > 4Rto4KN > 15Rto15K (Figure 9B of Wong et al., 2020). In comparing theoretical and experimental LLPS, a low theoretical can practically mean no experimental LLPS when the theoretical is below the freezing temperature of the real system (Lin et al., 2016; Brady et al., 2017). Figure 7a shows that even the highest for 15Rto15K (at model [NaCl] = 480 mM) is essentially at the same level as for WT at [NaCl] = 0 (). This MD prediction is consistent with the combined experimental observations of no LLPS for 15Rto15K up to at least [NaCl] = 2 M and no LLPS for WT Caprin1 at [NaCl] = 0 (Figure 9B and C of Wong et al., 2020).

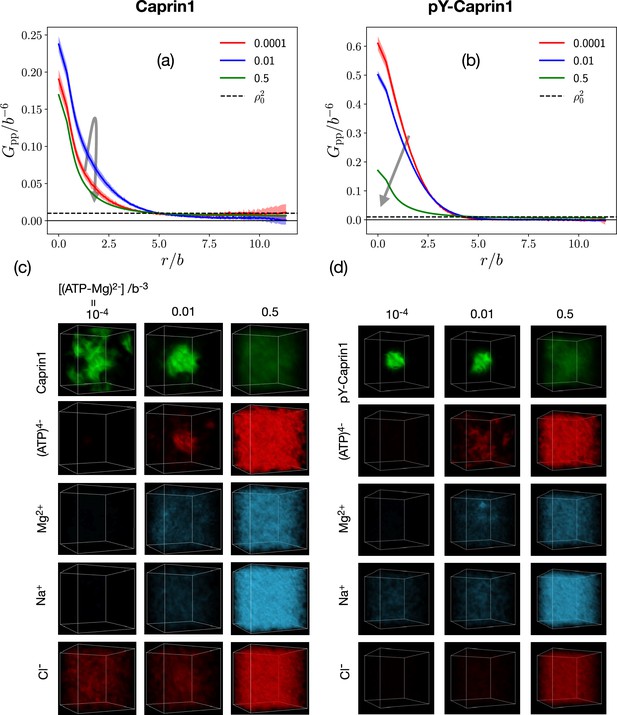

Field-theoretic simulation (FTS) is an efficient tool for studying multiple-component phase properties

We next turn to modeling of Caprin1 or pY-Caprin1 LLPS modulated by both ATP-Mg and NaCl. Because tackling such many-component LLPS systems using rG-RPA or explicit-ion MD is numerically challenging, here we adopt the complementary FTS approach (Fredrickson, 2006) outlined in Materials and methods for this aspect of our investigation. FTS is based on complex Langevin dynamics (Parisi, 1983; Klauder, 1983), which is related to an earlier formulation for stochastic quantization (Parisi and Wu, 1981; Chan and Halpern, 1986) and has been applied extensively to polymer solutions (Fredrickson et al., 2002; Fredrickson, 2006). Recently, FTS has provided insights into charge-sequence-dependent LLPS of IDRs (McCarty et al., 2019; Pal et al., 2021; Wessén et al., 2022a; Lin et al., 2019b; Lin et al., 2023). The starting point of FTS is identical to that of rG-RPA. FTS invokes no RPA and is thus advantageous over rG-RPA in this regard, although it is still limited by the lattice size used for simulation and its restricted treatment of excluded volume (Pal et al., 2021). Here we apply the protocol detailed in Pal et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2023.

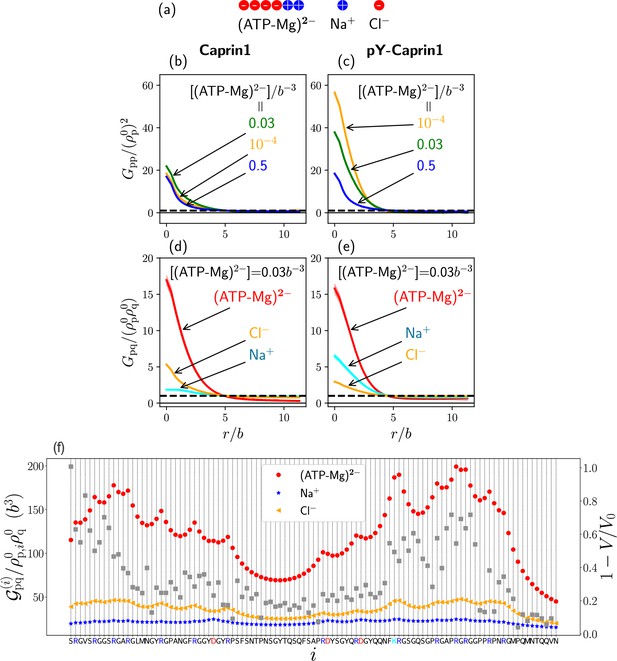

A simple model of ATP-Mg for FTS

Going beyond the single-bead model for (ATP-Mg)2− in our analytical rG-RPA theory (Figure 2), we now adopt a 6-bead polymeric representation of (ATP-Mg)2− (Figure 8a) in which four negative and two positive charges serve to model ATP4− and Mg2+ respectively. Modeling (ATP-Mg)2− as a short charged polymer enables application of existing FTS formulations for multiple charge sequences to systems with IDRs and (ATP-Mg)2−. While the model in Figure 8a does not capture structural details, its charge distribution does correspond roughly to that of the chemical structure of (ATP-Mg)2−. In developing FTS models involving IDR, (ATP-Mg)2−, and NaCl, we first assume for simplicity that (ATP-Mg)2− does not dissociate and consider systems consisting of any given overall concentrations of IDR and (ATP-Mg)2− wherein all positive and negative charges on the IDR and (ATP-Mg)2− are balanced, respectively, by Cl− and Na+ to maintain overall electric neutrality (Figure 8a).

FTS rationalizes experimental observation of Caprin1-ATP interactions.

(a) The 6-bead model for (ATP-Mg)2− and the single-bead models for monovalent salt ions used in the present FTS. (b–e) Normalized protein-protein correlation functions at three [(ATP-Mg)2−] values (b, c) and protein-ion correlation functions (Equation 7) at [(ATP-Mg)2−]/b−3 = 0.03 (d, e) for Caprin1 (b, d) and pY-Caprin1 (c, e), computed for Bjerrum length . Horizontal dashed lines are unity baselines (see text). (f) Values of position-specific integrated correlation (left vertical axis) correspond to the relative contact frequencies between individual residues labeled by i along the Caprin1 IDR sequence with q = (ATP-Mg)2−, Na+, or Cl− under the same conditions as (d) (Equation 9) (color symbols). Included for comparison are experimental NMR volume ratios data on site-specific Caprin1-ATP association (Kim et al., 2021). decreases with increased contact probability, although a precise relationship is yet to be determined. Thus, the plotted (grey data points, right vertical scale) is expected to correlate with contact frequency.

-

Figure 8—source data 1

Numerical values of all theoretical and experimental data points plotted in Figure 8.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/100284/elife-100284-fig8-data1-v1.xlsx

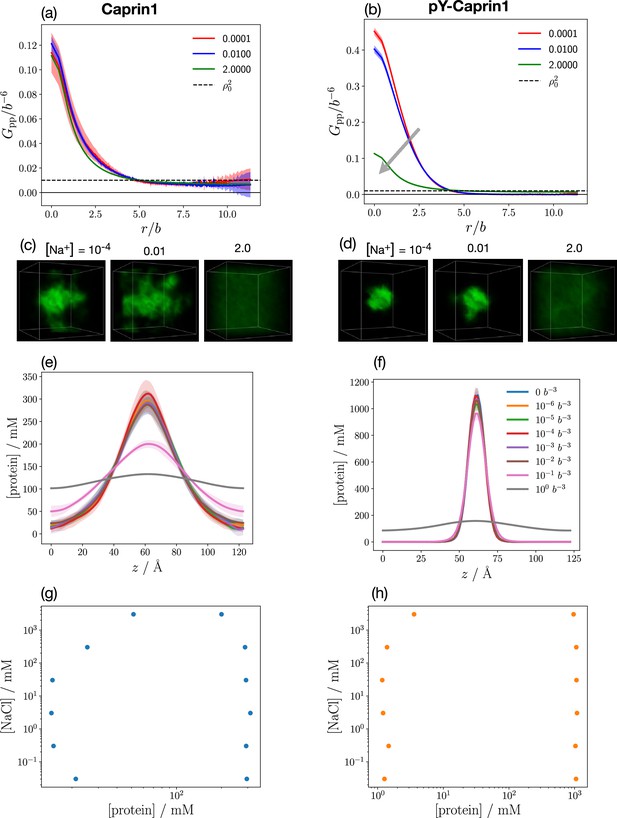

Phase behaviors can be probed by FTS density correlation functions

LLPS of FTS systems can be monitored by correlation functions (Pal et al., 2021). Here, we compute intra-species IDR self-correlation functions (Figure 8b and c) and inter-species cross-correlation functions between the IDR and (ATP-Mg)2− or NaCl (Figure 8d and e) at three different overall [(ATP-Mg)2−] = 10−4b−3, 0.03b−3, and 0.5b−3, where b may be taken as the peptide virtual bond length ≈ 3.8 Å (Materials and methods). The correlation functions in Figure 8b–e are normalized by overall densities of the IDR and for (ATP-Mg)2−, Na+ or Cl−, wherein density is the bead density for the given molecular species in units of . LLPS of the IDR is signaled by in Figure 8b and c dropping below the unity baseline (dashed) at large distance because it implies a spatial region with depleted IDR below the overall concentration, which is possible only if the IDR is above the overall concentration in at least another spatial region. In other words, for large indicates that IDR concentration is heterogeneous and thus the system is phase separated. For small , is generally expected to increase because IDR chain connectivity facilitates correlation among residues local along the chain. On top of this, LLPS propensity may be quantified by for small because a higher value indicates a higher tendency for different chains to associate and thus a higher LLPS propensity (Pal et al., 2021).

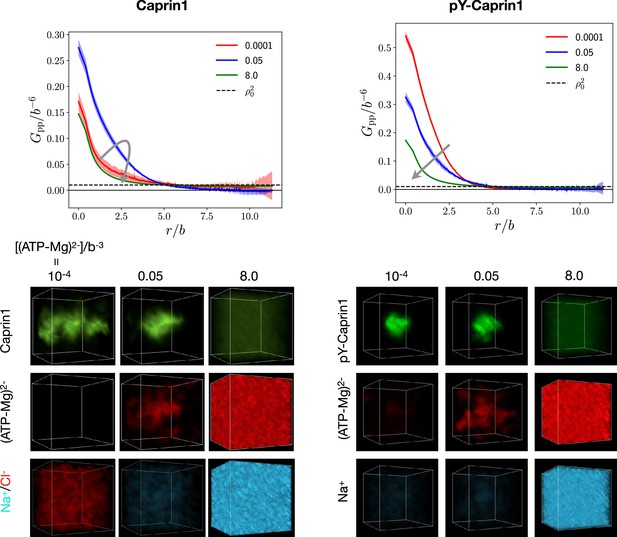

FTS rationalizes [ATP-Mg]-modulated Caprin1 reentrant phase behaviors and their colocalization in the condensed phase

[(ATP-Mg)2−]-modulated reentrance is predicted by FTS for Caprin1 but not for pY-Caprin1: When [(ATP-Mg)2−]/b−3 varies from 10−4 to 0.03 to 0.5, small-r values of the Caprin1 in Figure 8b initially increase then decrease, whereas the corresponding small-r values of the pY-Caprin1 in Figure 8c decrease monotonically, consistent with rG-RPA (Figure 2g, h, k, l) and experiment (Figure 3). The inter-species cross-correlations in Figure 8d, e show further that when an IDR condensed phase is present at [(ATP-Mg)2−] = 0.03b−3 (as indicated by large- behaviors of in Figure 8b, c), (ATP-Mg)2− is colocalized with Caprin1 or pY-Caprin1 (high value of for small ) in the IDR-condensed droplet. By comparison, the variation of [Na+] and [Cl–] is much weaker. For Caprin1, Cl– is enhanced over Na+ in the Caprin1 condensed phase (small- of the former larger than the latter in Figure 8d), but the reverse is seen for pY-Caprin1 (Figure 8e). This FTS-predicted difference, most likely arising from the positive net charge on Caprin1 and the smaller negative net charge on pY-Caprin1, is consistent with the MD results in Figure 4e-h and Appendix 1—figure 3.

FTS rationalizes experimentally observed residue-specific binding of Caprin1 with ATP-Mg

The propensities for (ATP-Mg)2−, Na+, and Cl– to associate with each residue along the Caprin1 IDR () in FTS are quantified by the residue-specific integrated correlation in Figure 8f, which is the integral of the corresponding from to a relative short cutoff distance to provide a relative contact frequency for residue and ionic species q to be in spatial proximity (Materials and methods and Appendix 1). Notably, the residue-position-dependent integrated correlation for (ATP-Mg)2− varies significantly, exhibiting much larger values near the N-terminal and a little before the C-terminal but weaker correlation elsewhere (Figure 8f, red symbols). The two regions of high integrated correlation (i.e., favorable association) coincide with regions with high sequence concentration of positively charged residues. This FTS prediction is remarkably similar to the experimental NMR finding that binding between (ATP-Mg)2− and Caprin1 occurs strongly at the arginine-rich N- and C-terminal regions, as indicated by the volume ratio data in Figure 1C of Kim et al., 2021 that quantifies the ratio of peaks in NMR spectra in the presence and absence of trace amounts of ATP-Mn. For comparison with the FTS results, this set of experimental data is replotted as in Figure 8f (grey symbols, right vertical axis) to illustrate the similarity in experimental and theoretical trends because is expected to trend with contact frequency. Corresponding FTS results for Na+ and Cl− in Figure 8f exhibit much less residue-position-dependent variation, with Cl− displaying only slightly enhanced association in the same arginine-rich regions, and Na+ showing even less variation, presumably because the positive charges on Caprin1 are already essentially neuralized by the locally associated (ATP-Mg)2− or Cl– ions. The theory-experiment agreement in Figure 8f regarding ATP-Caprin1 interactions indicates once again that electrostatics is an important driving force underlying many aspects of experimentally observed Caprin1–(ATP-Mg)2− association.

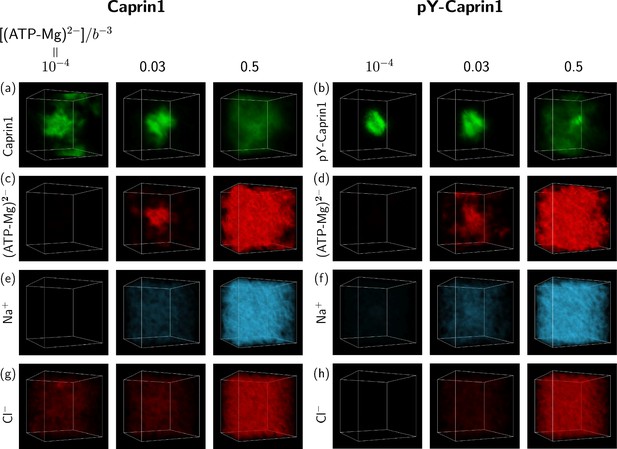

FTS snapshots of [ATP-Mg]-modulated reentrant phase behaviors and Caprin1-ATP-Mg colocalization

The above FTS-predicted trends are further illustrated in Figure 9 by field snapshots. Such FTS snapshots are generally useful for visualization and heuristic understanding (McCarty et al., 2019; Pal et al., 2021; Wessén et al., 2022a), including insights into subtler aspects of spatial arrangements exemplified by recent studies of subcompartmentalization entailing either co-mixing or demixing in multiple-component LLPS that are verifable by explicit-chain MD (Pal et al., 2021; Wessén et al., 2022a). Now, trends deduced from the correlation functions in Figure 8 are buttressed by the representative snapshots in Figure 9: As the bead density of (ATP-Mg)2− is increased from to to , the spatial distribution of Caprin1 evolves from an initially dispersed state to a concentrated droplet to a (reentrant) dispersed state again (Figure 9a), whereas the initial dense pY-Caprin1 droplet becomes increasingly dispersed monotonically (Figure 9b). Colocalization of (ATP-Mg)2− with both the Caprin1 (Figure 9c) and pY-Caprin1 (Figure 9d) droplets is clearly visible at [(ATP-Mg)2−] = 0.03b−3, though the degree of colocalization is appreciably higher for Caprin1 than for pY-Caprin1. This is likely because the positive net charge of Caprin1 is more attractive to (ATP-Mg)2−. By comparison, variations in Na+ and Cl− distribution between Caprin1/pY-Caprin1 dilute and condensed phases are not so discernible in Figure 9e–h, consistent with the small differences in the corresponding FTS correlation functions (Figure 8d and e).

FTS rationalizes colocalization of ATP-Mg with the Caprin1 condensate.

FTS snapshots are from simulations at (same as that for Figure 8). Spatial distributions of real positive parts of the density fields for the protein (a, b), (ATP-Mg)2− (c, d), Na+ (e, f), and Cl– (g, h) components are shown by three snapshots each for Caprin1 (left panels) and pY-Caprin1 (right panels) at different [(ATP-Mg)2−] values as indicated. Colocalization of (ATP-Mg)2− with the Caprin1 condensed droplet is clearly seen in the [(ATP-Mg)2−]/b−3 = 0.03 panel of (c).

Robustness of general trends predicted by FTS

We have also assessed the generality of the results in Figures 8 and 9 by considering three variations in the molecular species treated by FTS: (i) Caprin1 or pY-Caprin1 with only Na+ and Cl– but no (ATP-Mg)2− (Appendix 1—figure 4), (ii) Caprin1 with (ATP-Mg)2− and either Na+ or Cl– (but not both) to maintain overall charge neutrality or pY-Caprin1 with (ATP-Mg)2− and Na+ as counterion but no Cl– (Appendix 1—figure 5), and (iii) Caprin1 or pY-Caprin1 with ATP4−, Mg2+, Na+ and Cl− (Appendix 1—figure 6). Despite these variations in FTS models, Appendix 1—figures 4–6 consistently show reentrant behavior for Caprin1 but not pY-Caprin1 and Appendix 1—figures 5 and 6 both exhibit colocalization of ATP with condensed Caprin1, suggesting that these features are robust consequences of the basic electrostatics at play in Caprin1/pY-Caprin1 + ATP-Mg + NaCl systems.

Discussion

It is reassuring that, in agreement with experiment, all of our electrostatics-based theoretical approaches consistently predict salt-dependent reentrant phase behaviors for Caprin1, whereas pY-Caprin1 LLPS propensity decreases monotonically with increasing salt (Figures 2, 4, 8 and 9). This effect applies to small monovalent salts exemplified by Na+ and Cl– as well as to our electrostatics-based single- and multiple-bead models of (ATP-Mg)2− or ATP4−, with ATP exhibiting a significant colocalization with the Caprin1 condensed phase (Figures 2g, h, k, l , 9c) attributable to the higher valency of (ATP-Mg)2− and ATP4− than that of monovalent ions. As mentioned above, the difference in salt-dependent LLPS of Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 originates largely from the polyelectrolytic nature of Caprin1 and the polyampholytic nature of pY-Caprin1 (Lin et al., 2020) corresponding, respectively, to the ‘high net charge’ and ‘screening’ classes of IDPs in a more recent analysis (MacAinsh et al., 2024).

Related studies of electrostatic effects on biomolecular condensates

Our theoretical predictions are also largely in agreement with recent computational studies on salt concentrations in the dilute versus condensed phases (Zheng et al., 2020) and salt-dependent reentrant behaviors (Krainer et al., 2021) of other biomolecular condensates, including explicit-water, explicit-ion atomic simulations with preformed condensates of the N-terminal RGG domain of LAF-1 (Zheng et al., 2020) and of the highly positive proline-arginine 25-repeat dipeptide PR25 (Garaizar and Espinosa, 2021).

A recent study examines salt-dependent reentrant LLPSs of full-length FUS (WT and G156E mutant), TDP-43, bromodomain-containing protein 4 (Brd4), sex-determining region Y-box 2 (Sox2), and annexin A11 (Krainer et al., 2021). Unlike the requirement of a nonzero monovalent salt concentration for Caprin1 LLPS, LLPS is observed for all these six proteins with KCl, NaCl, or other salts at concentrations as low as 50 mM. Also unlike Caprin1, their protein condensates dissolve at intermediate salt then re-appear at higher salt, a phenomenon the authors rationalize by a tradeoff between decreasing favorability of cation-anion interactions and increasing favorability of cation-cation, cation-π, hydrophobic, and other interactions with increasing monovalent salt (Krainer et al., 2021).

Two reasons may account for this difference. First, Caprin1 does not phase separate at low salt because it is a relatively strong polyelectrolyte (NCPR = +13/103 = +0.126). By comparison, five of the six proteins in Krainer et al., 2021 are much weaker polyelectrolytes or not at all, with NCPR = +14/526 = +0.0266, +13/526 = +0.0247, −7/80 = −0.0875, 0, and +3/326 = +0.00920, respectively, for FUS (WT, mutant), TDP-43, Brd4, and A11. Apparently, their weak electrostatic repulsions can be overcome by favorable nonelectrostatic interactions alone to enable LLPS.

Second, compared to Caprin1, the proteins in Krainer et al., 2021 are either significantly larger (WT and mutant FUS) or significantly more hydrophobic and aromatic (the other four proteins), both properties are conducive to LLPS. For instance, although Sox2’s NCPR = +14/88 = +0.159 is higher than that of Caprin1, among Sox2’s amino acid residues, 21/88 = 23.9% are large hydrophobic or aromatic residues leucine (L), isoleucine (I), valine (V), methionine (M), phenylalanine (F), or tryptophan (W), and 17/88 = 19.3% are large aliphatic residues L, I, V, or M. This amino acid composition suggests that hydrophobic or π-related interactions in Sox2 can be sufficient to overcome electrostatic repulsion to effectuate LLPS at zero salt. In contrast, the Caprin1 IDR contains merely one L; only 10/103 = 9.7% of the residues of Caprin1 are in the L, I, V, M, F, W hydrophobic/aromatic category and only 6/103 = 5.8% are in the L, I, V, M aliphatic category. The corresponding aliphatic fractions of TDP-43, Brd4 and A11, at 21/80 = 26.3%, 33/132 = 25%, and 90/326 = 27.6%, respectively, are also significantly higher than that of Caprin1.

Effects of salt on biomolecular LLPS

Effects of salts on LLPS, including partitioning of salt into polymer-rich phases, are of long-standing interest in polymer physics (Jedlinska and Riggleman, 2023). In the biomolecular condensate context, the versatile functional roles of salts are highlighted by the interplay between electrostatic and cation-π interactions (Hazra and Levy, 2023; Kim et al., 2017), salts’ modulating effects on heat-induced LLPSs of RNAs (Wadsworth et al., 2023), their regulation of condensate liquidity (Morishita et al., 2023), and even their potential impact in extremely high-salt exobiological environments (Fetahaj et al., 2021). While some of these recent studies focus primarily on salts’ electrostatic screening effects without changing the signs of the effective polymer charge-charge interaction (Hazra and Levy, 2023), effective attractions between like charges bridged by salt or other oppositely-charged ions (Orkoulas et al., 2003) as illustrated by Caprin1 (Figures 5f and 6) and a recent study of A1-LCD (MacAinsh et al., 2024) are likely needed to account for phenomena such as salt-induced dimerization of highly charged, medically relevant arginine-rich cell-penetrating short peptides (Tesei et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022). In this regard, it should be noted that positively and negatively charged salt ions can also coordinate with backbone carbonyls and amides, respectively, in addition to coordinating with charged amino acid sidechains (MacAinsh et al., 2024). The impact of such effects, which are not considered in the present coarse-grained models, should be ascertained by further investigations using atomic simulations (MacAinsh et al., 2024; Rauscher and Pomès, 2017; Zheng et al., 2020).

Tielines in protein-salt phase diagrams

In view of Caprin1’s polyelectrolytic nature, the mildly negative tieline slopes in Figure 2a and b are consistent with rG-RPA predictions for a fully charged polyelectrolyte (Figure 10a of Lin et al., 2020). This depletion of monovalent salt in the condensed phase is similar to that observed in the complex coacervation of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes (Radhakrishna et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Herrera et al., 2023). By comparison, the positive rG-RPA tieline slopes for polyampholytic pY-Caprin1 (Figure 2c and d), confirmed by MD in Figure 4f and h, are appreciably steeper than that predicted for fully charged (±1) diblock polyampholytes by rG-RPA and the essentially flat tielines predicted by FTS (Fig. 10b of Lin et al., 2020 and Figure 7 of Danielsen et al., 2019). Whether this difference originates from the presence of divalently charged (−2) phosphorylated sites in pY-Caprin1 remains to be elucidated. In any event, tieline analysis is generally instrumental for revealing details, such as stoichiometry, of the interactions driving multiple-component biomolecular (Lin et al., 2022; Posey et al., 2024; Qian et al., 2022); rG-RPA should be broadly useful as a computationally efficient tool for this purpose (Lin et al., 2020).

Counterion valency

Our rG-RPA prediction that the maximum condensed-phase [Caprin1] at low [Na+] is substantially higher with divalent than with monovalent counterions is in line with early findings that higher-valency counterions are more effective in bridging polyelectrolyte interactions to favor LLPS (Olvera de la Cruz et al., 1995) and recent observations that salt ions with higher valencies enhance biomolecular LLPS (Lenton et al., 2021; Crabtree et al., 2023). The possibility that this counterion/salt effect on LLPS may be exploited more generally for biological functions and/or biomedical applications remains to be further explored. In this regard, while recognizing that ATP can engage in π-related interactions (Kota et al., 2024; Kang et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2019), our electrostatics-based perspective of ATP-dependent reentrant phase behaviors is consistent with recent observations on polylysine LLPS modulated by enzymatically catalyzed ATP turnovers (Herrera et al., 2023; Nakashima et al., 2018). More broadly, differential effects of salt ions on biomolecular LLPS can also arise from the sizes and charge densities of the ions—properties related to the Hofmeister phenomena (Hribar et al., 2002; Lo Nostro and Ninham, 2012)—even for ions with the same valency (Posey et al., 2024). These features should be addressed in future theoretical models as well.

Prospective extensions of the present theoretical methodology

Beyond the above comparisons, further experimental testing of other aspects of our theoretical predictions should be pursued, especially those pertaining to pY-Caprin1. Future theoretical efforts should address a broader range of scenarios by independent variations of [ATP4−], [Mg2+], [Na+], [Cl−] and to account for nonelectrostatic aspects of ATP-Mg dissociation (Wessén et al., 2022b) with predictions such as tieline slopes analyzed in detail to delineate effects of sizes, charge densities (Posey et al., 2024), and configurational entropy of salt ions (Adhikari et al., 2018) as well as solvent quality (Li et al., 2021). In addition to our basic modeling constructs, the impact of excluded volume and solvent/cosolute-mediated temperature-dependent effective interactions should be incorporated. Excluded volume is known to affect LLPS (Danielsen et al., 2019), demixing of IDP species in condensates (Pal et al., 2021), and partition of salt ions in polymer LLPS (Li et al., 2018). Moreover, LCST can be driven not only by hydrophobicity (Cinar et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2018; Dignon et al., 2019a) but also by electrostatics, as suggested by experiment on complex coacervates of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes (Ali et al., 2019). Bringing together these features into a comprehensive formulation will afford a more accurate physical picture.

Summary

To recapitulate, we have employed three complementary theoretical and computational approaches to account for the interplay between sequence pattern, phosphorylation, counterion, and salt in the phase behaviors of IDPs. Application to the Caprin1 IDR and its phosphorylated variant pY-Caprin1 provides physical rationalization for a variety of trends observed in experiments, including reentrance behaviors and very substantial ATP colocalization. These findings support a significant—albeit not exclusive—role of electrostatics in these biophysical phenomena, providing physical insights into effects of sequence-specific charge-charge interactions on ATP-modulated physiological functions of biomolecular condensates such as regulation of ion concentrations. The approach developed here should be of general utility as a computationally efficient tool for hypothesis generation, design of new experiments, exploration and testing of biophysical scenarios, as well as a starting point for more sophisticated theoretical/computational modeling.

Materials and methods

Further details of the experimental and theoretical/computational methodologies outlined below are provided in Appendix 1.

Experimental sample preparation

Request a detailed protocolThe low complexity 607–709 domain of Caprin1 was expressed and purified as before (Kim et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021). WT Caprin1 was used in all experiments except those on [NaCl] dependence reported in Table 1 and Figure 3a, for which a double mutant was used because residue pairs N623-G624 and N630-G631 in WT Caprin1 form isoaspartate (IsoAsp) glycine linkages over time which alters the charge distribution of the IDR (Wong et al., 2020).

Phosphorylation of the Caprin1 IDR

Request a detailed protocolPhosphorylation of the WT Caprin1 IDR was performed as described in our prior study (Kim et al., 2019) by using the kinase domain of mouse Eph4A (587-896) (Wiesner et al., 2006) with an N-terminal His-SUMO tag.

Determination of phase diagrams

Request a detailed protocolWe established phase diagrams for Caprin1 and pY-Caprin1 by measuring the protein concentrations in dilute and condensed phases across a range of [NaCl]s (Figure 1c and d). Initially homogenizing the two phases of the demixed samples into a milky dispersion through vortexing, ∼200 μL aliquots were then incubated in a PCR thermocycler with a heated lid at 90 °C, in triplicate, for a minimum of one hour. During incubation, the condensed phase settled and formed a clear phase at the bottom. For concentration measurements, the samples were diluted in 6 M GdmCl and 20 mM NaPi (pH 6.5). The dilute phase (top layer) was analyzed through a tenfold dilution of 10 μL samples, and the condensed phase (bottom layer) was analyzed through 250- to 500-fold dilution of 2 or 10 μL samples. Notably, using a positive displacement pipettor (Eppendorf) and tips was essential for accurately pipetting the viscous condensed phase.

Concentrations of salt and ATP-Mg in dilute and condensed phases

Request a detailed protocolInductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) measurements of [Na+] were performed using a Thermo Scientific iCAP Pro ICP-OES instrument in axial mode. ICP-OES was also used to determine [ATP] and [Mg2+] (Table 2). The detection of phosphorus and magnesium served as proxies for quantifying ATP and Mg2+ levels, respectively. Standard curves were prepared using solutions with known [ATP] and [Mg2+], ranging from 0 to 90 ppm for ATP and 0–25 ppm for Mg2+.

Caprin1 phase separation propensity at high-salt concentrations