Odd-paired controls frequency doubling in Drosophila segmentation by altering the pair-rule gene regulatory network

Abstract

The Drosophila embryo transiently exhibits a double-segment periodicity, defined by the expression of seven 'pair-rule' genes, each in a pattern of seven stripes. At gastrulation, interactions between the pair-rule genes lead to frequency doubling and the patterning of 14 parasegment boundaries. In contrast to earlier stages of Drosophila anteroposterior patterning, this transition is not well understood. By carefully analysing the spatiotemporal dynamics of pair-rule gene expression, we demonstrate that frequency-doubling is precipitated by multiple coordinated changes to the network of regulatory interactions between the pair-rule genes. We identify the broadly expressed but temporally patterned transcription factor, Odd-paired (Opa/Zic), as the cause of these changes, and show that the patterning of the even-numbered parasegment boundaries relies on Opa-dependent regulatory interactions. Our findings indicate that the pair-rule gene regulatory network has a temporally modulated topology, permitting the pair-rule genes to play stage-specific patterning roles.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18215.001eLife digest

The basic body plan of an animal is set up in the early embryo, where key developmental genes are expressed in specific patterns across the organism. These patterns emerge from the way in which the proteins encoded by these genes act to regulate each other’s expression. The fruit fly Drosophila is often used as a simple model for studying how regulatory interactions between genes lead to the formation of complex developmental patterns.

One example is segmentation, the process by which the trunk (main body) region of the Drosophila embryo is subdivided into 14 segments. A group of transcription factor proteins that are encoded by the so-called “pair-rule” genes play a crucial role in producing the final pattern. Early in development, the pair-rule genes are expressed in patterns of seven stripes, dividing the embryo into double segment units. As the embryo develops, these patterns change to form more precise patterns of 14 stripes, corresponding to single segments. Although many of the regulatory interactions between the pair-rule genes were known, how the system works as a whole to produce this change in expression patterns was not well understood.

Clark and Akam have now examined how the patterns of pair-rule gene expression change over time inside fly embryos. This revealed that a “rewiring” of the network of pair-rule genes occurs at the end of the seven stripe stage to produce fourteen stripes. Further investigation revealed that a transcription factor encoded by the gene odd-paired causes this rewiring, and that the timing of the expression of the Odd-paired protein determines when the rewiring happens.

Further studies could now investigate whether Odd-paired’s role as a timer extends to species where segments emerge sequentially, instead of the simultaneous formation of segments seen in Drosophila. Future challenges will be to find out how Odd-paired interacts with other pair-rule transcription factors, and whether there are other timing factors that help to coordinate embryonic patterning.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18215.002Introduction

Segmentation is a developmental process that subdivides an animal body axis into similar, repeating units (Hannibal and Patel, 2013). Segmentation of the main body axis underlies the body plans of arthropods, annelids and vertebrates (Telford et al., 2008; Balavoine, 2014; Graham et al., 2014). In arthropods, segmentation first involves setting up polarised boundaries early in development to define 'parasegments' (Martinez-Arias and Lawrence, 1985). Parasegment boundaries are maintained by an elaborate and strongly-conserved signalling network of 'segment-polarity' genes (Ingham, 1988; Perrimon, 1994; DiNardo et al., 1994; Sanson, 2001; Janssen and Budd, 2013).

In all arthropods yet studied, the segmental stripes of segment-polarity genes are initially patterned by a group of transcription factors known as the 'pair-rule' genes (Green and Akam, 2013; Peel et al., 2005; Damen et al., 2005). The pair-rule genes were originally identified in a screen for mutations affecting the segmental pattern of the Drosophila melanogaster larval cuticle (Nüsslein-Volhard and Wieschaus, 1980). They appeared to be required for the patterning of alternate segment boundaries (hence 'pair-rule') and were subsequently found to be expressed in stripes of double-segment periodicity (Hafen et al., 1984; Akam, 1987).

Early models of Drosophila segmentation suggested that the blastoderm might be progressively patterned into finer-scale units by some reaction-diffusion mechanism that exhibited iterative frequency-doubling (reviewed in Jaeger, 2009). The discovery of a double-segment unit of organisation seemed to support these ideas, and pair-rule patterning was therefore thought to be an adaptation to the syncytial environment of the early Drosophila embryo, which allows diffusion of gene products between neighbouring nuclei. However, the transcripts of pair-rule genes are apically localised during cellularisation of the blastoderm, and thus pair-rule patterning occurs in an effectively cellular environment (Edgar et al., 1987; Davis and Ish-Horowicz, 1991). Furthermore, double-segment periodicity of pair-rule gene expression is also found in some sequentially segmenting ('short germ') insects (Patel et al., 1994), indicating that pair-rule patterning predates the evolution of simultaneous ('long germ') segmentation (Figure 1).

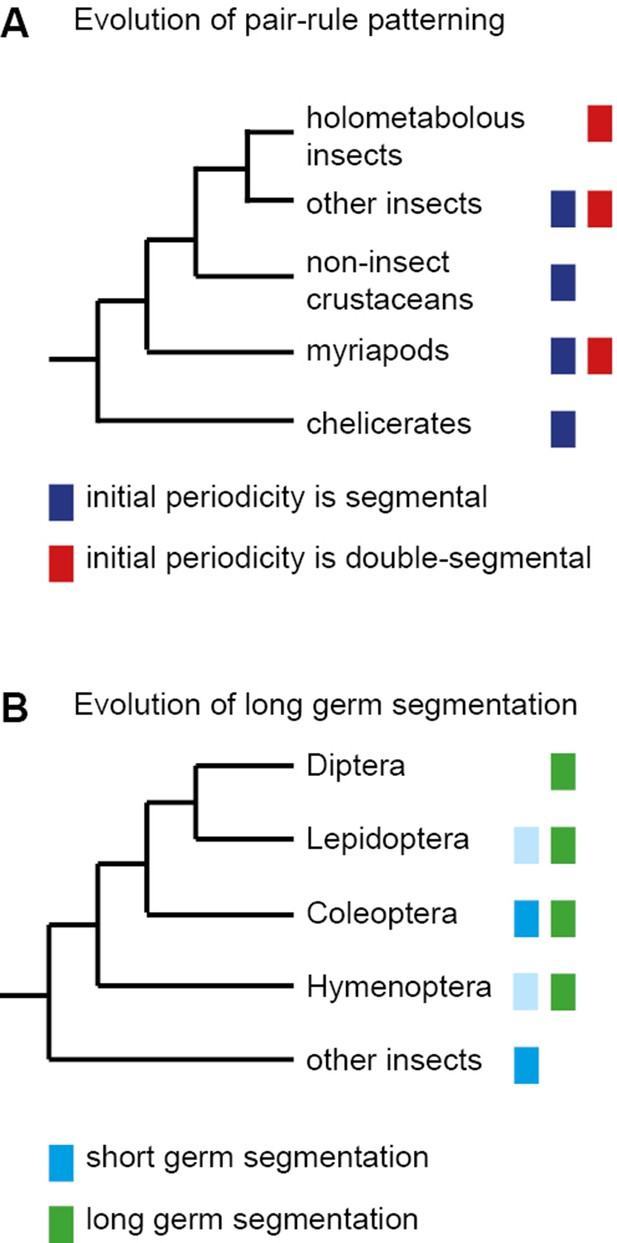

The evolution of pair-rule patterning predates the evolution of long germ segmentation.

(A) Single segment periodicity is ancestral in arthropod segmentation, being found in spiders, millipedes, crustaceans and some insects (Davis et al., 2005; Pueyo et al., 2008). 'Pair-rule' patterning, involving an initial double segment periodicity of pair-rule gene expression, appears to have evolved independently at least twice. It is found in insects and certain centipedes (Davis et al., 2001; Chipman et al., 2004). (B) Long germ segmentation is likely to have evolved independently multiple times within holometabolous insects, from an ancestral short germ state (Liu and Kaufman, 2005). Light blue boxes for the Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera indicate that short germ segmentation is relatively uncommon in these clades.

The next set of models for pair-rule patterning were motivated by genetic dissection of the early regulation of the segment-polarity gene engrailed (en). It was found that odd-numbered en stripes – and thus the anterior boundaries of odd-numbered parasegments (hereafter 'odd-numbered parasegment boundaries') – require the pair-rule gene paired (prd), but not another pair-rule gene fushi tarazu (ftz), while the opposite was true for the even-numbered en stripes and their associated ('even-numbered') parasegment boundaries (DiNardo and O'Farrell, 1987). Differential patterning of alternate segment-polarity stripes, combined with the observation that the different pair-rule genes are expressed with different relative phasings along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis, led to models where static, partially overlapping domains of pair-rule gene expression form a combinatorial regulatory code that patterns the blastoderm with single-cell resolution (DiNardo and O'Farrell, 1987; Gergen and Butler, 1988; Weir et al., 1988; Coulter et al., 1990; Morrissey et al., 1991).

However, pair-rule gene expression domains are not static. One reason for this is that their upstream regulators, the gap genes, are themselves dynamically expressed, exhibiting expression domains that shift anteriorly over time (Jaeger et al., 2004; El-Sherif and Levine, 2016). Another major reason is that, in addition to directing the initial expression of the segment-polarity genes, pair-rule genes also cross-regulate one another. Pair-rule proteins and transcripts turn over extremely rapidly (Edgar et al., 1986; Nasiadka and Krause, 1999), and therefore regulatory feedback between the different pair-rule genes mediates dynamic pattern changes throughout the period that they are expressed. Most strikingly, many of the pair-rule genes undergo a transition from double-segment periodicity to single-segment periodicity at the end of cellularisation. The significance of this frequency-doubling is not totally clear. In some cases, the late, segmental stripes are crucial for proper segmentation (Cadigan et al., 1994b), but in others they appear to be dispensable (Coulter et al., 1990; Fujioka et al., 1995), or their function (if any) is not known (Klingler and Gergen, 1993; Jaynes and Fujioka, 2004).

More recent models of pair-rule patterning recognise that the pair-rule genes form a complex gene regulatory network that mediates dynamic patterns of expression (Edgar et al., 1989; Sánchez and Thieffry, 2003; Jaynes and Fujioka, 2004). However, whereas other stages of Drosophila segmentation have been extensively studied from a dynamical systems perspective (reviewed in Jaeger, 2009; Grimm et al., 2010; Jaeger, 2011), we do not yet have a good systems-level understanding of the pair-rule gene network (Jaeger, 2009). This appears to be a missed opportunity: not only do the pair-rule genes exhibit fascinating transcriptional regulation, but their interactions are potentially very informative for comparative studies with short germ arthropods. These include the beetle Tribolium castaneum, in which the pair-rule genes form a segmentation oscillator (Sarrazin et al., 2012; Choe et al., 2006).

To better understand exactly how pair-rule patterning works in Drosophila, we carried out a careful analysis of pair-rule gene regulation during cellularisation and gastrulation, drawing on both the genetic literature and a newly generated dataset of double-fluorescent in situs. Surprisingly, we found that the majority of regulatory interactions between pair-rule genes are not constant, but undergo dramatic changes just before the onset of gastrulation. These regulatory changes mediate the frequency-doubling phenomena observed in the embryo at this time.

We then realised that all the regulatory interactions specific to the late pair-rule gene regulatory network seem to require the non-canonical pair-rule gene odd-paired (opa). opa was identified through the original Drosophila segmentation screen as being required for the patterning of the even-numbered parasegment boundaries (Jürgens et al., 1984). However, rather than being expressed periodically like the rest of the pair-rule genes, opa is expressed ubiquitously throughout the trunk region (Benedyk et al., 1994). The reported appearance of Opa protein temporally correlates with the time we see regulatory changes in the embryo, indicating that it may be directly responsible for these changes. We propose that Opa provides a source of temporal information that acts combinatorially with the spatial information provided by the periodically expressed pair-rule genes. Pair-rule patterning thus appears to be a two-stage process that relies on the interplay of spatial and temporal signals to permit a common set of patterning genes to carry out stage-specific regulatory functions.

Results

High-resolution spatiotemporal characterisation of wild-type pair-rule gene expression

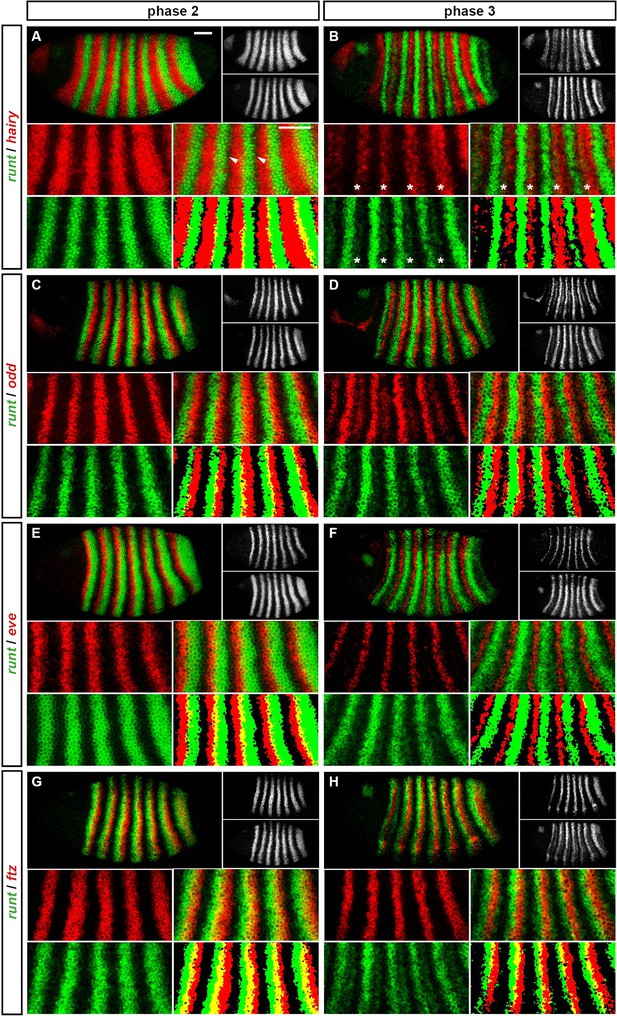

We carried out double fluorescent in situ hybridisation on fixed wild-type Drosophila embryos for all pairwise combinations of the pair-rule genes hairy, even-skipped (eve), runt, fushi tarazu (ftz), odd-skipped (odd), paired (prd) and sloppy-paired (slp). Because the expression patterns of these genes develop dynamically but exhibit little embryo-to-embryo variability (Surkova et al., 2008; Little et al., 2013; Dubuis et al., 2013), we were able to order images of individual embryos by inferred developmental age. This allowed us to produce pseudo time-series that illustrate how pair-rule gene expression patterns change relative to one another during early development (Figure 2).

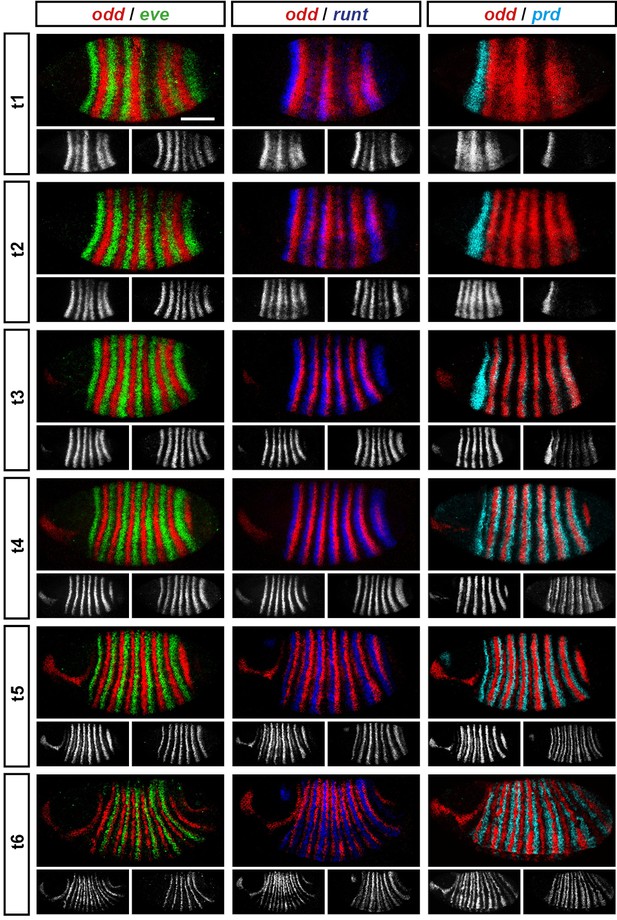

Representative double fluorescent in situ hybridisation data for three combinations of pair-rule genes.

This figure shows a small subset of our wild-type dataset. Each column represents a different pairwise combination of in situ probes, while each row shows similarly-staged embryos of increasing developmental age. All panels show a lateral view, anterior left, dorsal top. Individual channels are shown in grayscale below each double-channel image. For ease of comparison, the signal from each gene is shown in a different colour in the double-channel images. Time classes are arbitrary, meant only to illustrate the progressive stages of pattern maturation between early cellularisation (t1) and late gastrulation (t6). Note that the developing pattern of odd expression in the head provides a distinctive and reliable indicator of embryo age. Scale bar = 100 μm. The complete dataset is available from the Dryad Digital Repository (Clark and Akam, 2016).

The expression profile of each individual pair-rule gene has been carefully described previously (Hafen et al., 1984; Ingham and Pinchin, 1985; Macdonald et al., 1986; Kilchherr et al., 1986; Gergen and Butler, 1988; Coulter et al., 1990; Grossniklaus et al., 1992), and high-quality relative expression data are available for pair-rule proteins (Pisarev et al., 2009). In addition, expression atlases facilitate the comparison of staged, averaged expression profiles of many different blastoderm patterning genes at once (Fowlkes et al., 2008). However, because the pair-rule genes are expressed extremely dynamically and in very precise patterns, useful extra information can be gleaned by directly examining relative expression patterns in individual embryos. In particular, we have found these data invaluable for understanding exactly how stripe phasings change over time, and for interrogating regulatory hypotheses. In addition, we have characterised pair-rule gene expression up until early germband extension, whereas blastoderm expression atlases stop at the end of cellularisation.

Our entire wild-type dataset (32 gene combinations, >600 individual embryos) is available from the Dryad Digital Repository (Clark and Akam, 2016). We hope it proves useful to the Drosophila community.

Three main phases of pair-rule gene expression

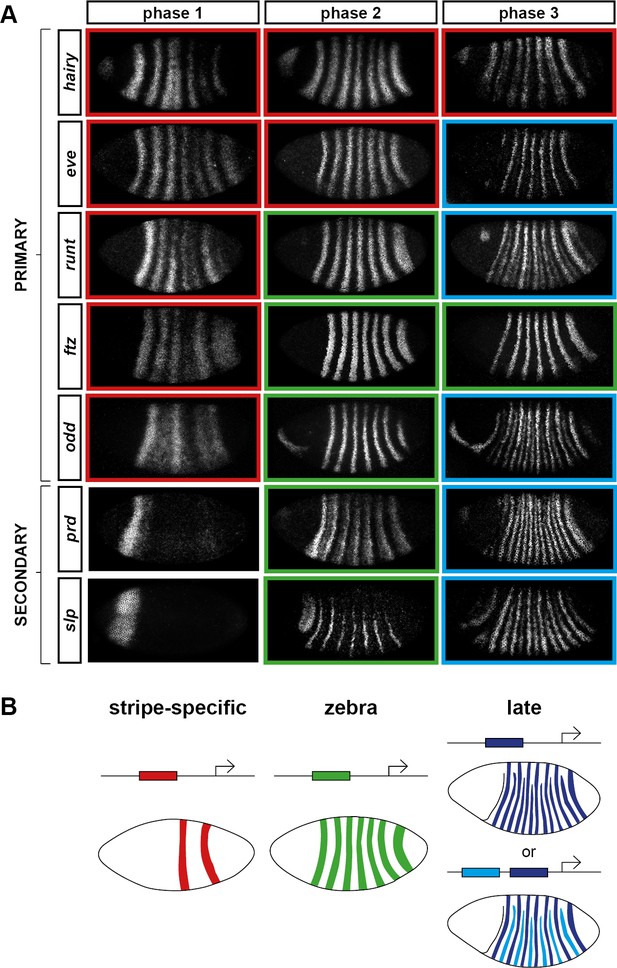

We classify the striped expression of the pair-rule genes into three temporal phases (Figure 3A). Phase 1 (equivalent to phase 1 of Schroeder et al., 2011; timepoint 1 in Figure 2) corresponds to early cellularisation, before the blastoderm nuclei elongate. Phase 2 (spanning phases 2 and 3 of Schroeder et al., 2011; timepoints 2–4 in Figure 2) corresponds to mid cellularisation, during which the plasma membrane progressively invaginates between the elongated nuclei. Phase 3 (starting at phase 4 of Schroeder et al., 2011 but continuing beyond it; timepoints 5–6 in Figure 2) corresponds to late cellularisation and gastrulation. Our classification is a functional one, based on the times at which different classes of pair-rule gene regulatory elements (Figure 3B) have been found to be active in the embryo.

Three phases of pair-rule gene expression, usually mediated by different classes of regulatory element.

(A) Representative expression patterns of each of the seven pair-rule genes at phase 1 (early cellularisation), phase 2 (mid cellularisation) and phase 3 (gastrulation). Pair-rule genes are classified as 'primary' or 'secondary' based on their regulation and expression during phase 1 (see text). All panels show a lateral view, anterior left, dorsal top. Note that the cephalic furrow may obscure certain anterior stripes during phase 3. (B) Illustrative diagrams of the different kinds of regulatory elements mediating pair-rule gene expression. 'Stripe-specific' elements are regulated by gap genes and give rise to either one or two stripes each. 'Zebra' elements are regulated by pair-rule genes and give rise to seven stripes. 'Late' expression patterns may be generated by a single-element generating segmental stripes, or by a combination of two elements each generating a distinct pair-rule pattern. The coloured outlines around the panels in (A) correspond to the colours of the different classes of regulatory elements in (B), and indicate how each phase of expression of a given pair-rule gene is thought to be regulated. See text for details.

During phase 1, expression of specific stripes is established through compact enhancer elements mediating gap gene inputs (Howard et al., 1988; Goto et al., 1989; Harding et al., 1989; Pankratz and Jäckle, 1990). hairy, eve and runt all possess a full set of these 'stripe-specific' elements, together driving expression in all seven stripes, while ftz lacks an element for stripe 4, and odd lacks elements for stripes 2, 4 and 7 (Schroeder et al., 2011). These five genes are together classified as the 'primary' pair-rule genes, because in all cases the majority of their initial stripe pattern is established de novo by non-periodic regulatory inputs. The regulation of various stripe-specific elements by gap proteins has been studied extensively (for example Small et al., 1992, 1996).

Phase 2 is dominated by the expression of so-called 'zebra' (or '7-stripe') elements (Hiromi et al., 1985; Dearolf et al., 1989; Butler et al., 1992). These elements, which tend to be relatively large (Gutjahr et al., 1994; Klingler et al., 1996; Schroeder et al., 2011), are regulated by pair-rule gene inputs and thus produce periodic output patterns. The stripes produced from these elements overlap with the stripes generated by stripe-specific elements, and often the two sets of stripes appear to be at least partially redundant. For example, ftz and odd lack a full complement of stripe-specific elements (see above), while the stripe-specific elements of runt are dispensable for segmentation (Butler et al., 1992). Neither hairy nor eve appears to possess a zebra element, and thus their expression during phase 2 is driven entirely by their stripe-specific elements. (Note that the 'late' (or 'autoregulatory') element of eve (Goto et al., 1989; Harding et al., 1989) does generate a periodic pattern and has therefore been considered to be analogous to the zebra elements of other pair-rule genes. However, because it is not expressed until phase 3 (Schroeder et al., 2011), we do not classify it as such.)

In addition to the five primary pair-rule genes, there are two other pair-rule genes, prd and slp, that turn on after regular periodic patterns of the other genes have been established. These genes possess only a single, anterior stripe-specific element, and their trunk stripes are generated by a zebra element alone (Schroeder et al., 2011). Because (ignoring the head stripes) these genes are regulated only by other pair-rule genes, and not by gap genes, they are termed as the 'secondary' pair-rule genes.

The third, 'late' phase of expression is the least understood. Around the time of gastrulation, most of the pair-rule genes undergo a transition from double-segmental stripes to single-segmental stripes. For prd, this happens by splitting of its early, broad pair-rule stripes. In contrast, odd, runt and slp show intercalation of 'secondary' stripes between their 'primary' 7-stripe patterns. Secondary stripes of eve also appear at gastrulation, but these 'minor' stripes (Macdonald et al., 1986) are extremely weak (usually undetectable in our fluorescent in situs), and not comparable to the rapidly developing segmental expression of prd, odd, runt and slp. Expression of hairy and ftz remains double segmental.

In some cases, discrete enhancer elements have been found that mediate just the secondary stripes (Klingler et al., 1996), while in other cases, all 14 segmental stripes are likely to be regulated coordinately (Fujioka et al., 1995). In certain cases, non-additive interactions between enhancers play a role in generating the segmental pattern (Prazak et al., 2010; Gutjahr et al., 1994). The functional significance of the late patterns is not always clear, since they are usually not reflected in pair-rule gene mutant cuticle phenotypes (Kilchherr et al., 1986; Coulter et al., 1990).

In the remainder of this paper, we investigate the nature and causes of the pattern transitions that occur between the end of phase 2 and the beginning of phase 3. A detailed analysis of the timing and dynamics of pair-rule gene expression during phase 2 will be covered elsewhere.

Frequency-doubling of different pair-rule gene expression patterns is almost simultaneous, and coincides with segment-polarity gene activation

As noted above, four of the seven pair-rule genes undergo a transition from double-segment periodicity to regular single-segment periodicity at the end of cellularisation (Figure 3). These striking pattern changes could be caused simply by feedback interactions within the pair-rule and segment-polarity gene networks. Alternatively, they could be precipitated by some extrinsic temporal signal (or signals).

Comparing between genes, we find that the pattern changes develop almost simultaneously (Figure 4; Figure 4—figure supplement 1), although there are slight differences in the times at which the first signs of frequency-doubling become detectable. (The prd trunk stripes split just before the odd secondary stripes start to appear, while the secondary stripes of slp and runt appear just after). These events appear to be spatiotemporally modulated: they show a short but noticeable AP time lag, and also a DV pattern – frequency-doubling occurs first mid-laterally, and generally does not extend across the dorsal midline. In addition, the secondary stripes of slp are not expressed in the mesoderm, while the ventral expression of odd secondary stripes is only weak.

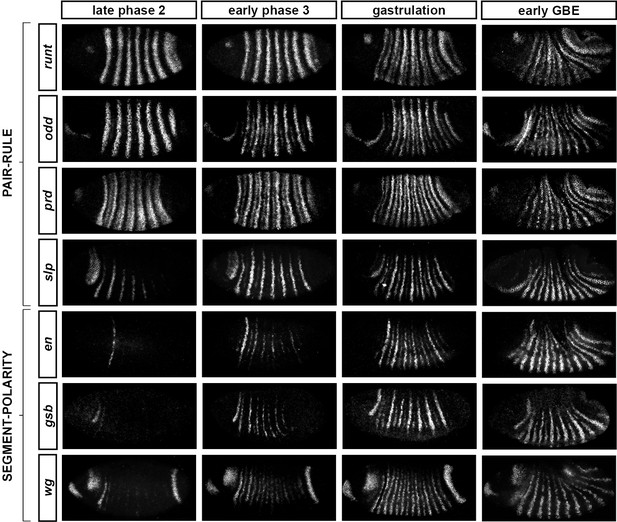

Frequency-doubling of pair-rule gene expression patterns is almost simultaneous and coincides with the first expression of the segment-polarity genes.

Each row shows the expression of a particular pair-rule gene or segment-polarity gene, while each column represents a particular developmental timepoint. Late phase 2 and early phase 3 both correspond to late Bownes stage 5; gastrulation is Bownes stage 6, and early germband extension is Bownes stage 7 (Bownes, 1975; Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein, 1985). All panels show a lateral view, anterior left, dorsal top. GBE = germband extension. The figure represents about 20 min of development at 25°C.

We also investigated the timing of the frequency-doubling events relative to the appearance of expression of the segment-polarity genes en, gooseberry (gsb) and wingless (wg) (Figure 4; Figure 4—figure supplement 2). We find that the spatiotemporal pattern of segment-polarity gene activation coincides closely with that of pair-rule frequency-doubling – starting at the beginning of phase 3, and rapidly progressing over the course of gastrulation. Only around 20 min separate a late stage 5 embryo (with double-segment periodicity of pair-rule gene expression and no segment-polarity gene expression) from a late stage 7 embryo (with regular segmental expression of both pair-rule genes and segment-polarity genes) (Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein, 1985).

We can make three conclusions from the timing of these events. First, segment-polarity gene expression cannot be precipitating the frequency-doubling of pair-rule gene expression, because frequency-doubling occurs before segment-polarity proteins would have had time to be synthesised. Second, the late, segmental patterns of pair-rule gene expression do not play a role in regulating the initial expression of segment-polarity genes, because they are not reflected at the protein level until after segmental patterns of segment-polarity gene transcripts are observed. Third, the synchrony of pair-rule gene frequency-doubling and segment-polarity gene activation is consistent with co-regulation of these events by a single temporal signal.

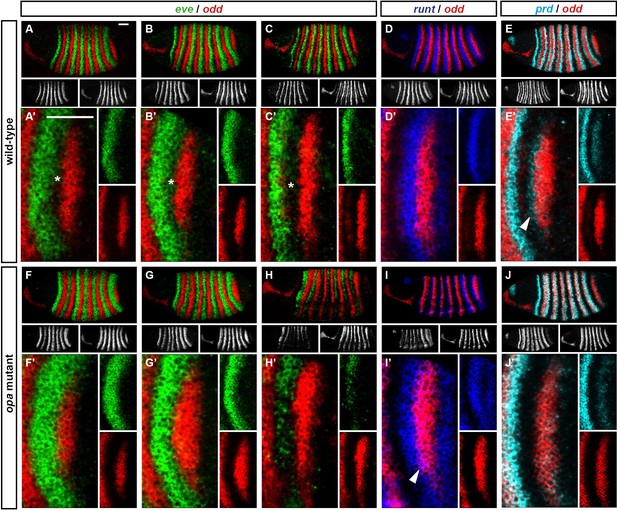

The transition to single-segment periodicity is mediated by altered regulatory interactions

It is clear that a dramatic change overtakes pair-rule gene expression at gastrulation. For a given gene, an altered pattern of transcriptional output could result from an altered spatial pattern of regulatory inputs, or, alternatively, altered regulatory logic. Pair-rule proteins provide most of the spatial regulatory input for pair-rule gene expression at both phase 2 and phase 3. Therefore, the fact that the distributions of pair-rule proteins are very similar at the end of phase 2 and the beginning of phase 3 (Pisarev et al., 2009) suggests that it must be the 'input-output functions' of pair-rule gene transcription that change to bring about the new expression patterns.

For example, consider the relative expression patterns of prd and odd (Figure 5). There is abundant experimental evidence that the splitting of the prd stripes is caused by direct repression by Odd protein. The primary stripes of odd lie within the broad prd stripes, and the secondary interstripes that form within the prd stripes at gastrulation correspond precisely to those cells that express odd (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the prd stripes do not split in odd mutant embryos (Baumgartner and Noll, 1990; Saulier-Le Dréan et al., 1998), and prd expression is largely repressed by ectopically expressed Odd protein (Saulier-Le Dréan et al., 1998; Goldstein et al., 2005).

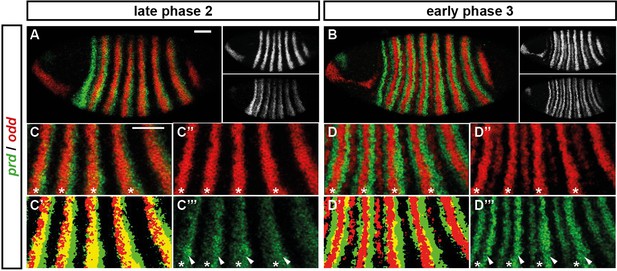

Odd does not repress prd transcription until phase 3.

Relative expression of prd and odd is shown in a late phase 2 embryo (just prior to frequency doubling) and an early phase 3 embryo (showing the first signs of frequency doubling). (A, B) Whole embryos, lateral view, anterior left, dorsal top. Individual channels are shown to the right of each double-channel image, in the same vertical order as the panel label. (C, D) Blow-ups of expression in stripes 2–6; asterisks mark the location of odd primary stripes. Thresholded images (C’, D’) highlight regions of overlapping expression (yellow pixels). Considerable overlap between prd and odd expression is observed at phase 2 but not at phase 3. Note that the prd expression pattern is the combined result of initially broad stripes of medium intensity, and intense two-cell wide 'P' stripes overlapping the posterior of each of the broad stripes (arrowheads in C’’’, D’’’). The two sets of stripes are mediated by separate stretches of DNA (Gutjahr et al., 1994), and must be regulated differently, since the 'P' stripes remain insensitive to ectopic Odd even during phase 3 (Saulier-Le Dréan et al., 1998; Goldstein et al., 2005). Scale bars = 50 μm.

However, prior to prd stripe splitting, prd and odd are co-expressed in the same cells, with no sign that prd is sensitive to repression by Odd (Figure 5C). Because prd expression begins at a time when Odd protein is already present (Pisarev et al., 2009), this co-expression cannot be explained by protein synthesis delays. We therefore infer that Odd only becomes a repressor of prd at gastrulation, consistent with previous observations that aspects of Odd regulatory activity are temporally restricted (Saulier-Le Dréan et al., 1998).

This apparent temporal switch in the regulatory function of Odd is not unique. We have carefully examined pair-rule gene stripe phasings just before and just after the double-segment to single-segment transition, and find that these patterns do indeed indicate significant changes to the control logic of multiple pair-rule genes. The results of this analysis are presented in Appendix 1. In summary, a number of regulatory interactions seem to disappear at the beginning of phase 3: repression of odd by Hairy, repression of odd by Eve, and repression of slp by Runt. These regulatory interactions are replaced by a number of new interactions: repression of prd by Odd, repression of odd by Runt, repression of runt by Eve and repression of slp by Ftz. At the same time that these regulatory changes are observed, new elements for eve and runt turn on and various segment-polarity genes start to be expressed.

The outcome of all these regulatory changes is a coordinated transition to single-segment periodicity. We have schematised this transition in Figure 6. Our diagrams are in broad agreement with the interpretation of Jaynes and Fujioka (Jaynes and Fujioka, 2004), although we characterise the process in greater temporal detail and distinguish between transcript and protein distributions at each timepoint.

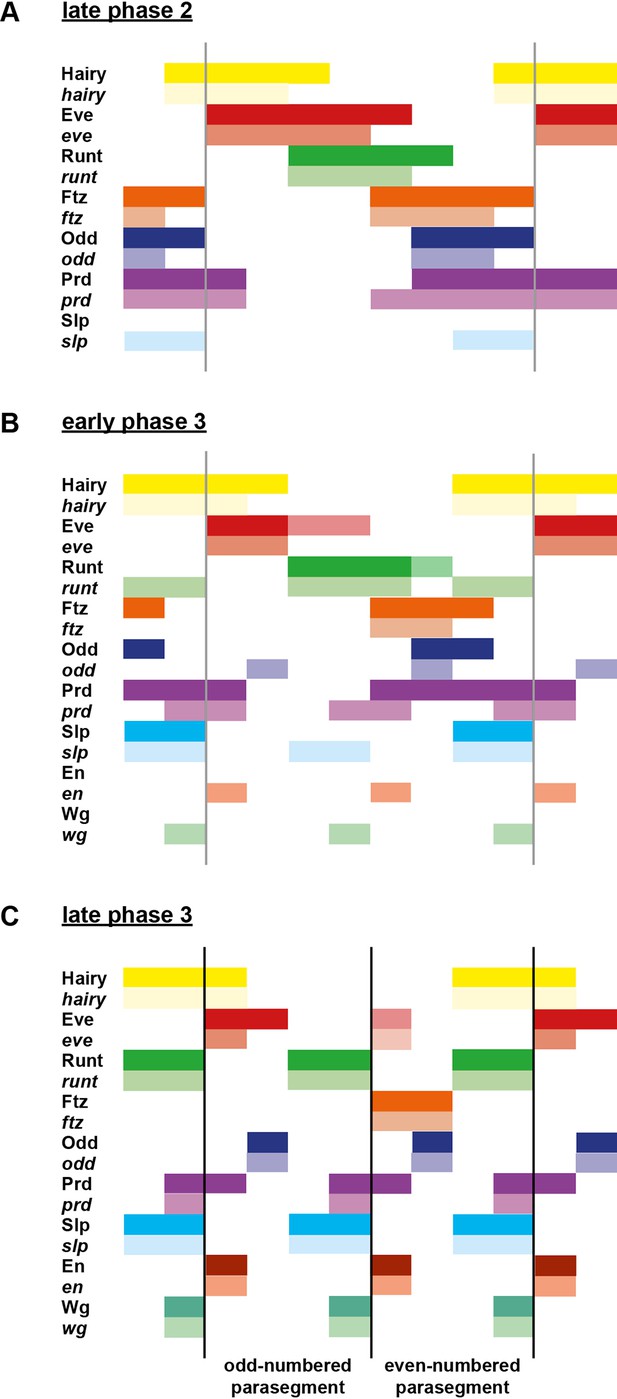

Schematic diagram of the transition to single-segment periodicity.

Schematic diagram showing segmentation gene expression at late phase 2 (A), early phase 3 (B) and late phase 3 (C). The horizontal axis represents an idealised portion of the AP axis (~12 nuclei across). The grey vertical lines in (A,B) demarcate a double parasegment repeat (~8 nuclei across), while black lines in (C) indicate future parasegment boundaries. The patterns of protein expression (intense colours) and transcript expression (paler colours) of the pair-rule genes are shown at each timepoint. Those of the segment-polarity genes en and wg are additionally shown at the later timepoints. Transcript distributions were inferred from our double in situ data, while pair-rule protein distributions were inferred mainly from triple antibody stains in the FlyEx database (Pisarev et al., 2009). Additional protein expression information for late phase 3 (equivalent to the onset of germband extension) was gathered from published descriptions (Frasch et al., 1987; DiNardo et al., 1985; van den Heuvel et al., 1989; Gutjahr et al., 1993; Lawrence and Johnston, 1989; Carroll et al., 1988). Fading expression of Eve and Runt is represented by lighter red and green sections in (B). The transient 'minor' stripes of Eve are represented by faint red in (C). Note that this diagram does not capture the graded nature of pair-rule protein distributions during cellularisation.

A candidate temporal signal: Odd-paired

Having identified the regulatory changes detailed above, we wanted to know how they are made to happen in the embryo. Because they all occur within a very short time window (Figure 4), they could potentially all be co-regulated by a single temporal signal that would instruct a regulatory switch. We reasoned that if this hypothetical signal were absent, the regulatory changes would not happen. This would result in a mutant phenotype in which frequency-doubling events do not occur, and segment-polarity expression is delayed.

We then realised that this hypothetical phenotype was consistent with descriptions of segmentation gene expression in mutants of the non-canonical pair-rule gene, odd-paired (opa) (Benedyk et al., 1994). This gene is required for the splitting of the prd stripes and the appearance of the secondary stripes of odd and slp (Baumgartner and Noll, 1990; Benedyk et al., 1994; Swantek and Gergen, 2004). It is also required for the late expression of runt (Klingler and Gergen, 1993), and for the timely expression of en and wg (Benedyk et al., 1994).

The opa locus was originally isolated on account of its cuticle phenotype, in which odd-numbered segments (corresponding to even-numbered parasegments) are lost (Jürgens et al., 1984). For many years afterwards, opa was assumed to be expressed in a periodic pattern of double-segment periodicity similar to the other seven pair-rule genes (for example, see Coulter and Wieschaus, 1988; Ingham and Baker, 1988; Weir et al., 1988; Baumgartner and Noll, 1990; Lacalli, 1990). When opa, which codes for a zinc finger transcription factor, was finally cloned, it was found – surprisingly – to be expressed uniformly throughout the trunk (Benedyk et al., 1994). Presumed to be therefore uninstructive for spatial patterning, it has received little attention in the context of segmentation since. However, we realised that Opa could still be playing an important role in spatial patterning. By providing temporal information that would act combinatorially with the spatial information carried by the canonical pair-rule genes, Opa might permit individual pair-rule genes to carry out different patterning roles at different points in time.

Expression of opa spatiotemporally correlates with patterning events

We examined opa expression relative to other segmentation genes, and found an interesting correlation with the spatiotemporal pattern of segmentation (Figure 7). As previously reported (Benedyk et al., 1994), the earliest expression of opa is in a band at the anterior of the trunk, which we find corresponds quite closely with the head stripe of prd (data not shown). Expression in the rest of the trunk quickly follows, and persists until germband extension, at which point expression becomes segmentally modulated (Figure 7I).

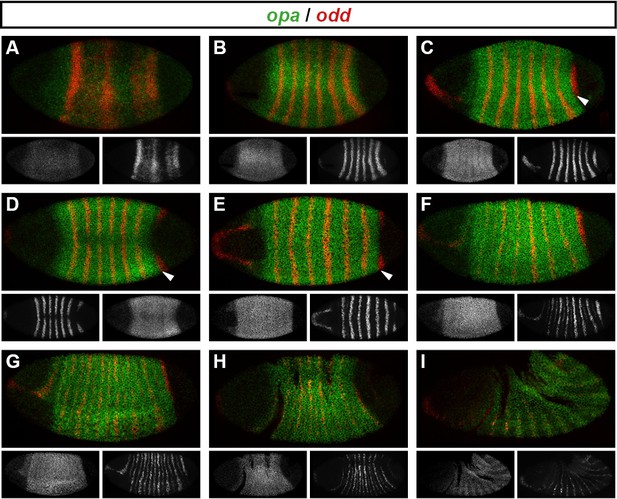

Spatiotemporal expression of opa relative to odd.

Expression of opa relative to odd from early cellularisation until mid germband extension. (A) phase 1, lateral view; (B) early phase 2; (C–E) late phase 2; (F) early phase 3; (G, H) gastrulation; (I) early germband extension. Anterior left; (A, B, C, F, I) lateral views; (D) dorsal view; (E) ventral view; (G) ventrolateral view; (H) dorsolateral view. Single-channel images are shown in greyscale below each double-channel image (opa on the left, odd on the right). Arrowheads in (C–E) point to the new appearance of odd stripe 7, which abuts the posterior boundary of the opa domain. Note that odd stripe 7 is incomplete both dorsally (D) and ventrally (E). By gastrulation, opa expression has posteriorly expanded to cover odd stripe 7 (G, H). opa expression becomes segmentally modulated during germband extension (I).

opa begins to be transcribed throughout the trunk during phase 1, before regular patterns of pair-rule gene expression emerge (Figure 7A). The sharp posterior border of the opa domain at first lies just anterior to odd stripe 7 (Figure 7B–E), but gradually shifts posteriorly over the course of gastrulation to encompass it (Figure 7F–H). Notably, odd stripe 7 is the last of the primary pair-rule gene stripes to appear, and segmentation of this posterior region of the embryo appears to be significantly delayed relative to the rest of the trunk (Kuhn et al., 2000).

The timing of opa transcription has been shown to rely on nuclear / cytoplasmic ratio (Lu et al., 2009), and begins relatively early during cellularisation. However, it takes a while for the opa expression domain to reach full intensity. Unlike the periodically expressed pair-rule genes, which have compact transcription units (all <3.5 kb, FlyBase) consistent with rapid protein synthesis, the opa transcription unit is large (~17 kb, FlyBase), owing mainly to a large intron. Accordingly, during most of cellularisation, we observe a punctate distribution of opa, suggestive of nascent transcripts located within nuclei (Figure 7—figure supplement 1). Unfortunately, the available polyclonal antibody against Opa (Benedyk et al., 1994) did not work well in our hands, so we have not been able to determine precisely what time Opa protein first appears in blastoderm nuclei. However, Opa protein levels have been reported to peak at late cellularisation and into gastrulation (Benedyk et al., 1994), corresponding to the time at which we observe regulatory changes in the embryo, and consistent with our hypothesised role of Opa as a temporal signal.

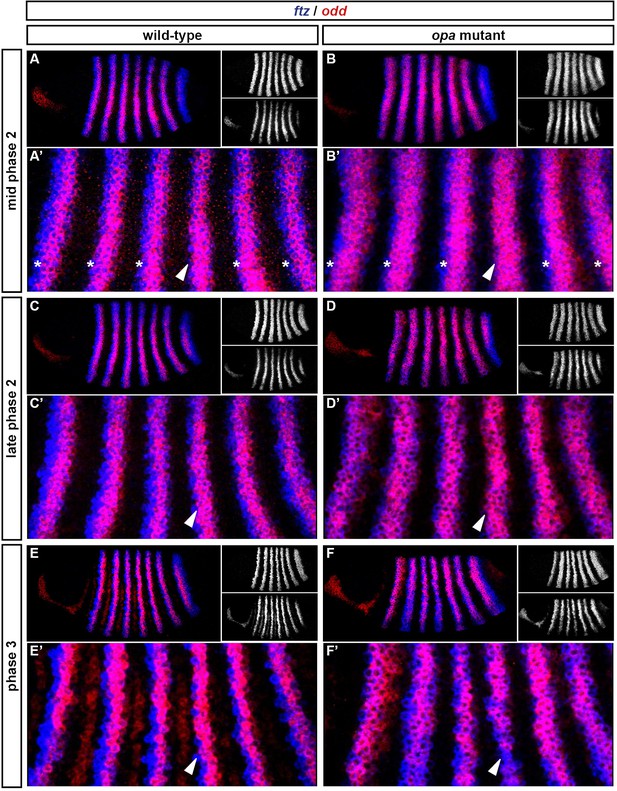

opa mutant embryos do not transition to single-segment periodicity at gastrulation

If our hypothesised role for Opa is correct, patterning of the pair-rule genes should progress normally in opa mutant embryos up until the beginning of phase 3, but not undergo the dramatic pattern changes observed at this time in wild-type. Instead, we would expect that the double-segmental stripes would persist unaltered, at least while the activators of phase 2 expression remain present. The pair-rule gene expression patterns that have been described previously in opa mutant embryos (see above) seem consistent with this prediction; however, we wanted to characterise the opa mutant phenotype in more detail to be sure.

Throughout cellularisation, we find that pair-rule gene expression is relatively normal in opa mutant embryos (Figure 8; Figure 8—figure supplement 1), consistent with our hypothesis that Opa function is largely absent from wild-type embryos during these stages. During late phase 2, we observe only minor quantitative changes to the pair-rule stripes: the odd primary stripes seem wider than normal, the prd primary stripes seem more intense than normal, and the slp primary stripes – which normally appear at the very end of phase 2 – are weakened and delayed.

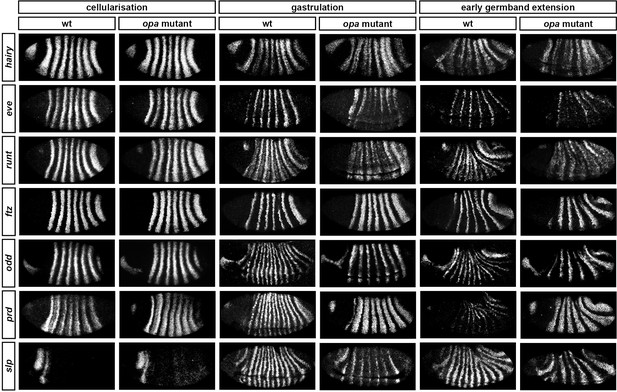

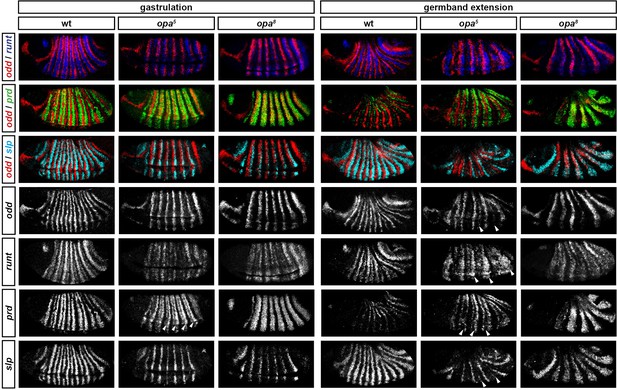

Pair-rule gene expression is perturbed from gastrulation onwards in opa mutant embryos.

Pair-rule gene expression in wild-type and opa mutant embryos at late cellularisation, late gastrulation, and early germband extension. During cellularisation, pair-rule gene expression in opa mutant embryos is very similar to wild-type. Expression from gastrulation onwards is severely abnormal; in particular, note that single-segment patterns do not emerge. All panels show a lateral view, anterior left, dorsal top.

In contrast, pair-rule gene expression becomes dramatically different from wild-type at gastrulation (Figure 8; Figure 8—figure supplement 2). Most notably, the transition from double-segment to single-segment periodicity is not observed for any pair-rule gene – for example, the secondary stripes of odd and slp do not appear, and the prd stripes do not split. In addition, the primary stripes of ftz and odd remain broad, similar to their expression during phase 2, rather than narrowing from the posterior as in wild-type.

Not all the pair-rule genes remain expressed in pair-rule stripes. Except for stripes 6 and 7, the runt primary stripes are lost, replaced by fairly ubiquitous weak expression which nevertheless retains a double-segmental modulation. eve expression – which has not to our knowledge been previously characterised in opa mutant embryos – fades from stripes 3–7, with no sign of the sharpened 'late' expression normally activated in the anteriors of the early stripes (Figure 8—figure supplement 5). hairy expression fades much as it does in wild-type, except that there is reduced separation between certain pairs of stripes.

The expression patterns seen at gastrulation persist largely unaltered into germband extension (Figure 8; Figure 8—figure supplement 3), with the exception that the slp stripes expand anteriorly, overlapping the domains of odd expression. The persistence of the intense prd stripes (which overlap those of ftz, odd and slp, and remain strongly expressed throughout germband extension) is especially notable given that prd expression fades from wild-type embryos soon after gastrulation.

Opa accounts for the regulatory changes observed at gastrulation

In summary, in opa mutant embryos odd, prd and slp remain expressed in pair-rule patterns after gastrulation, while expression of eve and runt is largely lost (schematised in Figure 8—figure supplement 4). The aberrant expression patterns of odd, prd and slp appear to directly reflect an absence of the regulatory changes normally observed in wild-type at phase 3. For example, the altered prd pattern is consistent with Odd failing to repress prd, indicating that Odd only acts as a repressor of prd in combination with Opa. Similarly, the expression pattern of slp is consistent with continued repression from Runt (a phase 2 interaction) and an absence of repression from Ftz (a phase 3 interaction), indicating that Runt only represses slp in the absence of Opa, while the opposite is true for Ftz. In Appendix 2, we demonstrate how an Opa-dependent switch from repression of odd by Eve (phase 2) to repression of odd by Runt (phase 3) is important for the precise positioning of the anterior borders of the odd primary stripes, in addition to being necessary for the emergence of the odd secondary stripes.

The loss of eve and runt expression in opa mutant embryos indicates first that the activators that drive expression of eve and runt during phase 2 do not persist in the embryo after the end of cellularisation, and second that the expression of these genes during phase 3 is activated by the new appearance of Opa. The inference of different activators at phase 2 and phase 3 is not too surprising for eve, which has phase 2 expression driven by stripe-specific elements and phase 3 expression driven by a separate 'late' element (see below). Indeed, expression of stripe-specific elements is known to fade away at gastrulation, as seen for endogenous expression of hairy (Ingham et al., 1985; Figure 8), for stripe-specific reporter elements of eve (Bothma et al., 2014), or for transgenic embryos lacking eve late element expression (Fujioka et al., 1995). However, a single stretch of DNA drives runt primary stripe expression at both phase 2 and phase 3 (Klingler et al., 1996). This suggests that the organisation and regulatory logic of this element may be complex, as it is evidently activated by different factors at different times.

Opa is also likely to contribute to the activation of the slp primary stripes, explaining why they are initially weaker than normal in opa mutant embryos. (However, in this case Opa must act semi-redundantly with other activators, in contrast to its effects on eve and runt.) A resulting delay in the appearance of Slp protein in opa mutant embryos could account for the broadened stripes of ftz and odd, which normally narrow during phase 3 in response to repression from Slp at the posterior. Alternatively, these regulatory functions of Slp could themselves be directly Opa-dependent.

Opa activates the eve 'late' element

Our discovery that Opa was required for late eve expression (Figure 8—figure supplement 5) was surprising, because the enhancer element responsible for this expression has been studied in detail (Goto et al., 1989; Harding et al., 1989; Jiang et al., 1991; Fujioka et al., 1996; Sackerson et al., 1999), and Opa has not previously been implicated in its regulation. The eve 'late' element is sometimes referred to as the eve 'autoregulatory' element, because expression from it is lost in eve mutant embryos (Harding et al., 1989; Jiang et al., 1991). However, the observed 'autoregulation' appears to be indirect (Goto et al., 1989; Manoukian and Krause, 1992; Fujioka et al., 1995; Sackerson et al., 1999). Instead of being directly activated by Eve, the element mediates regulatory inputs from repressors such as Runt and Slp, which are ectopically expressed in eve mutant embryos (Vavra and Carroll, 1989; Klingler and Gergen, 1993; Riechmann et al., 1997; Jaynes and Fujioka, 2004). The element is thought to be directly activated by Prd, and functional Prd-binding sites have been demonstrated within it (Fujioka et al., 1996). However, while Prd protein appears at roughly the right time to activate the eve late element (Pisarev et al., 2009), activation by Prd cannot explain all the expression generated from this element, because during early phase 3 it drives expression in many cells that do not express prd (Figure 8—figure supplement 6).

Instead, it seems that the eve late element is directly activated by Opa. The lack of late eve expression in opa mutant embryos cannot be explained by the ectopic expression of repressive inputs, since none of runt, odd or slp are ectopically expressed in the domains where eve late element expression would normally be seen (Figure 8; Figure 8—figure supplement 4). Furthermore, the total loss of eve expression in certain stripes despite the presence of appropriately positioned prd expression indicates that Prd alone is not sufficient to drive strong eve expression. Activation of en expression by Prd also requires the presence of Opa (Benedyk et al., 1994), suggesting that cooperative interactions between Prd and Opa might be common.

Opa regulatory activity may be concentration-dependent

Not all the Opa-dependent expression pattern changes we identified through our analysis of opa mutant embryos happen at exactly the same time in wild-type embryos. Specifically, the splitting of the prd stripes and the appearance of the slp primary stripes occur a few minutes earlier than the other changes, such as the appearance of the secondary stripes of odd and slp, and the late expression of eve. If we assume that Opa concentration increases in the embryo over time as more protein is synthesised, these timing discrepancies could be explained by the former events being driven a lower level of Opa activity than required for the latter events.

In order to investigate this hypothesis, we examined pair-rule gene expression in mutants for a 'weak' allele of opa (opa5, also known as opa13D92) which we presume to represent an opa hypomorph. Whereas mutants for the null allele we investigated (opa8, also known as opa11P32) develop cuticles with complete pairwise fusion of adjacent denticle belts, mutants for opa5 develop less severe patterning defects where denticle belts remain separate or only partially fuse (Baumgartner et al., 1994).

Figure 9 compares expression patterns in opa hypomorphic embryos to both the wild-type and null situations. At cellularisation, expression patterns are similar for all three genotypes (data not shown). At gastrulation, expression patterns in the hypomorphic embryos tend to resemble those in the null embryos. However, there are two significant differences, corresponding to the two Opa-dependent patterning events that occur first in wild-type embryos. First, the slp primary stripes are expressed more strongly in the hypomorphic embryos than in the null embryos (although their appearance is still slightly delayed), and second, the prd stripes in the hypomorphic embryos show weak expression in the centre of the stripes (arrowheads in Figure 9), a situation intermediate between the wild-type situation of full splitting, and the null situation of completely uniform stripes. Later, during germband extension, expression patterns in the hypomorphic embryos diverge further from the null situation, with multiple genes exhibiting evidence of Opa-dependent regulation (arrowheads in Figure 9). For example, the prd stripes fully split, some evidence of odd and slp secondary stripes can be seen, and strong runt expression is reinitiated.

Opa-dependent expression pattern changes are delayed in opa hypomorphic embryos.

Expression of selected pair-rule genes compared between embryos wild-type, hypomorphic (opa5), or null mutant (opa8) for opa. Arrowheads mark evidence of Opa-dependent regulatory interactions in opa5 embryos (see text for details). All panels show a lateral view, anterior left, dorsal top.

Together, this evidence suggests that different regulatory targets of Opa respond with differential sensitivity. As the level of Opa increases over time, 'sensitive' targets would show expression changes as soon as a low threshold of Opa activity was reached, whereas other targets would respond later, when a higher threshold was reached. In wild-type embryos, the low threshold events occur slightly earlier than the high threshold events, at late phase 2 rather than early phase 3. In opa hypomorphic embryos, in which the rate of increase in Opa activity would be slower, these events happen later but still in the same temporal sequence, with the low threshold events occurring at gastrulation, and the high threshold events not detected until germband extension. In opa null embryos, both classes of events of course do not happen at all.

opa mutant embryos fail to pattern the even-numbered parasegment boundaries

Explaining the aetiology of the opa pair-rule phenotype requires understanding why the loss of Opa activity results in the mispatterning of parasegment boundaries by segment-polarity genes. In wild-type embryos, en and wg are initially regulated cell-autonomously by pair-rule proteins (for example, see Ingham and Baker, 1988; Weir et al., 1988; Manoukian and Krause, 1993; Mullen and DiNardo, 1995). During germband extension, they become dependent on intercellular signalling for their continued expression, with the Wingless and Hedgehog signalling pathways forming a positive feedback loop that maintains each parasegment boundary (DiNardo et al., 1988, 1994; Perrimon, 1994; von Dassow et al., 2000).

Expression of en and wg has previously been characterised in opa mutant embryos, demonstrating that the even-numbered parasegment boundaries fail to establish properly (Benedyk et al., 1994; Ingham, 1986; DiNardo and O'Farrell, 1987; see also Figure 10—figure supplement 1). To summarise, although their initial appearance is somewhat delayed, the even-numbered wg stripes (which normally contribute to the odd-numbered parasegment boundaries) and some of the even-numbered en stripes (which normally contribute to the even-numbered parasegment boundaries) become established in their normal locations by the beginning of the germband extension. Later on in germband extension, odd-numbered en stripes become established adjacent to the even-numbered wg stripes, leading to the formation of the odd-numbered parasegment boundaries. In contrast, the odd-numbered wg stripes never appear, the even-numbered en stripes eventually fade away, and the even-numbered parasegment boundaries are not established.

Our characterisation of pair-rule gene expression in opa mutant embryos enables us to make sense of these patterns. First, Opa appears to regulate slp and wg in a very similar way (Figure 10—figure supplement 1). The even-numbered wg stripes overlap with the primary stripes of slp and show the same expression delays in opa mutant embryos, while the odd-numbered wg stripes and the slp secondary stripes, which would normally be activated at the same time and in the same places, both fail to appear. Second, the activation of en by Prd seems to strictly require Opa activity, whereas the activation of en by Ftz does not. Therefore, while the odd-numbered (Prd-activated) en stripes are initially absent in opa mutant embryos, some of the even-numbered (Ftz-activated) stripes do appear, although this is compromised by ectopic expression of Odd (Benedyk et al., 1994, Appendix 2). Third, the capacity for a partially specified parasegment boundary to later recover depends on the presence of an appropriate segmental pattern of pair-rule gene expression, despite these patterns arising too late to regulate the initial expression of segment-polarity genes at gastrulation.

For example, the Slp stripes play an important segment-polarity role during germband extension, defining the posterior half of each parasegment. They repress en expression and are also necessary for the maintenance of wg expression (Cadigan et al., 1994b). In the case of the odd-numbered parasegment boundaries, slp and wg are properly patterned in opa mutant embryos, but the en stripes are absent (Figure 10—figure supplement 1). However, repressors of en such as Odd and Slp are not ectopically expressed in their place. Therefore, the odd-numbered en stripes are able to be later induced in their normal positions, presumably in response to Wg signalling coming from the Slp primary stripes, and therefore properly patterned boundaries eventually emerge. However, in the case of the even-numbered parasegment boundaries, while the en stripes are usually present in opa mutant embryos, both the slp stripes and the wg stripes are not (Figure 10—figure supplement 1). The absence of the Slp secondary stripes means that the cells anterior to the even-numbered En stripes are not competent to express wg. Hedgehog signalling from the even-numbered En stripes is therefore unable to induce the odd-numbered wg stripes, and consequently the boundaries do not recover.

Based on regulatory interactions analysed in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2, we present an updated model for how the even-numbered parasegment boundaries are specified in wild-type embryos (Figure 10). We propose that the spatial information directly responsible for patterning these boundaries derives from overlapping domains of Runt and Ftz activity (Appendix 1—figure 3G,H). Ftz and Runt combinatorially specify distinct expression domains of slp, en and odd, by way of late acting, Opa-dependent regulatory interactions. As described above, the loss of these interactions in opa mutant embryos results in mispatterning of slp and odd (Figure 8—figure supplement 4), which later has significant repercussions for segment-polarity gene expression.

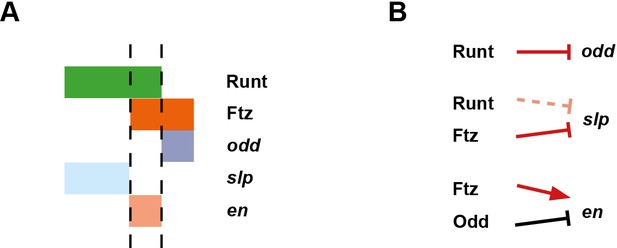

Model for the Opa-dependent patterning of the even-numbered parasegment boundaries.

(A) Schematic showing the phasing of odd, slp and en relative to Runt and Ftz protein at phase 3. The horizontal axis represents part of a typical double-segment pattern repeat along the AP axis of the embryo (~4 nuclei across, centred on an even-numbered parasegment boundary). (B) Inferred regulatory interactions governing the expression of odd, slp and en at phase 3. Regular arrows represent activatory interactions; hammerhead arrows represent repressive interactions. Solid arrows represent interactions that are currently in operation; pale dashed arrows represent those that are not. Red arrows represent interactions that depend on the presence of Opa protein. Overlapping domains of Runt and Ftz expression (A) subdivide this region of the AP axis into three sections (black dashed lines). Opa-dependent repression restricts odd expression to the posterior section, resulting in offset anterior boundaries of Ftz and Odd activity (Appendix 2—figure 1; Appendix 2—figure 1—figure supplement 2). slp expression is restricted to the anterior section by the combination of Opa-dependent repression from Ftz and Opa-dependent de-repression from Runt (Appendix 1—figure 2—figure supplement 1). en is restricted to the central section by the combination of activation from Ftz (likely partially dependent on Opa), and repression by Odd. Later, mutual repression between odd, slp and en will maintain these distinct cell states. The even-numbered parasegment boundaries will form between the en and slp domains. Note that, in this model, Eve has no direct role in patterning these boundaries.

Discussion

Opa alters the pair-rule network and temporally regulates segmentation

We have found that many regulatory interactions between the pair-rule genes are not constant over the course of Drosophila segmentation, but instead undergo coordinated changes at the end of cellularisation. We are not the first to notice that certain regulatory interactions do not apply to all stages of pair-rule gene expression (Baumgartner and Noll, 1990; Manoukian and Krause, 1992; Manoukian and Krause, 1993; Fujioka et al., 1995; Saulier-Le Dréan et al., 1998). However, cataloguing and analysing these changes for the whole pair-rule system led us to the realisation that they are almost simultaneous and mediate the transition from double-segment to single-segment periodicity. We propose that the product of the non-canonical pair-rule gene opa acts as a temporal signal that mediates these changes, and simultaneously activates the expression of segment-polarity genes. Analysis of pair-rule gene expression patterns in opa mutant embryos indicates that the phase-specific regulatory interactions we inferred from wild-type embryos appear to be modulated by Opa, and thus explained by the onset of Opa regulatory activity at gastrulation.

We argue that the pair-rule system should not be thought of as a static gene regulatory network, but rather two temporally and topologically distinct networks, each with its own dynamical behaviour and consequent developmental patterning role. Pair-rule patterning can therefore be thought of as a two-stage process. In the absence of Opa, the early network patterns the template for the odd-numbered parasegment boundaries. Then, when Opa turns on, Opa-dependent regulatory interactions lead to the patterning of the even-numbered parasegment boundaries. Each stage of patterning uses the same source of positional information (the primary stripes of the pair-rule genes), but uses different sets of regulatory logic to exploit this information in different ways.

Opa thus plays a crucial timing role in segmentation, orchestrating the transition from pair-rule to segmental patterning. Notably, the role of Opa in activating the initial stages of segment-polarity gene expression demonstrates that segment-polarity gene expression is not simply induced by the emergence of an appropriate pattern of pair-rule proteins, as in textbook models of hierarchical gene regulation. The necessity for an additional signal had been surmised previously, based on the delayed appearance of odd-numbered en stripes in cells already expressing Eve and Prd (Manoukian and Krause, 1993).

Because correct segmentation depends upon the initial expression of segment-polarity genes being precisely positioned, it is imperative that a regular pair-rule pattern is present before the segment-polarity genes first turn on. Therefore, explicit temporal control of segment-polarity gene activation by Opa makes good sense from a patterning perspective. There are likely to be a number of analogous regulatory signals that provide extrinsic temporal information to the Drosophila segmentation cascade. For example, a ubiquitously expressed maternal protein, Tramtrack, represses pair-rule gene expression during early embryogenesis, effectively delaying pair-rule gene expression until appropriate patterns of gap gene expression have been established (Harrison and Travers, 1990; Read et al., 1992; Brown and Wu, 1993).

What is the mechanism of Opa regulatory activity?

opa is the Drosophila ortholog of zinc finger of the cerebellum (zic) (Aruga et al., 1994). zic genes encode zinc finger transcription factors closely related to Gli proteins that have many important developmental roles.

In the Drosophila embryo, in addition to its role in segmentation, Opa is also involved in the formation of visceral mesoderm (Cimbora and Sakonju, 1995; Schaub and Frasch, 2013). Opa is later highly expressed in the larval and adult brain (FlyAtlas – Chintapalli et al., 2007) and is likely to be involved in neuronal differentiation (Eroglu et al., 2014). It is also involved in the regulation of adult head development (Lee et al., 2007).

The neuronal function is likely to reflect an ancestral role of Zic, as involvement of Zic genes in nervous system development and neuronal differentiation is pervasive throughout metazoans (Layden et al., 2010). Lineage-specific duplications have resulted in five zic genes in most vertebrate taxa, and seven in teleosts (Aruga et al., 2006; Merzdorf, 2007). While partial redundancy between these paralogs complicates the interpretation of mutant phenotypes, it is clear that in vertebrates Zic proteins play crucial roles in early embryonic patterning, neurogenesis, left-right asymmetry, neural crest formation, somite development, and cell proliferation (reviewed in Merzdorf, 2007; Houtmeyers et al., 2013).

Zic proteins have been shown to act both as classical DNA-binding transcription factors, and as cofactors that modulate the regulatory activity of other transcription factors via protein-protein interactions (reviewed in Ali et al., 2012; Winata et al., 2015). They show context-dependent activity and can both activate and repress transcription (Yang et al., 2000; Salero et al., 2001). In particular, they appear to be directly involved in the modulation and interpretation of Wnt and Hedgehog signalling (Murgan et al., 2015; Pourebrahim et al., 2011; Fujimi et al., 2012; Koyabu et al., 2001; Chan et al., 2011; Quinn et al., 2012). Finally, they may play a direct role in chromatin regulation (Luo et al., 2015).

The roles that Opa plays in the Drosophila segmentation network appear to be consistent with the mechanisms of Zic regulatory activity that have been characterised in vertebrates. Opa appears to transcriptionally activate a number of enhancers, including those driving late expression of eve, runt and slp. In the case of the slp enhancer, this has been verified experimentally (Sen et al., 2010). In other cases, the role of Opa is likely to be restricted to modulating the effect of other regulatory inputs, such as mediating the repressive effect of Odd on prd expression, or the activatory effect of Prd on en expression. It will be interesting to investigate the enhancers mediating late pair-rule gene expression and early segment polarity gene expression, and to determine how Opa interacts with them to bring about these varied effects.

Is Opa sufficient for the regulatory changes we observe at gastrulation?

Our data seem consistent with Opa being 'the' temporal signal that precipitates the 7 stripe to 14 stripe transition. However, it remains possible that Opa acts in conjunction with some other, as yet unidentified, temporally patterned factor, or has activity that is overridden during cellularisation by some maternal or zygotic factor that disappears at gastrulation. Indeed, combinatorial interactions with DV factors do seem likely to be playing a role in restricting the effects of Opa: despite the opa expression domain encircling the embryo, many Opa-dependent patterning events do not extend into the mesoderm or across the dorsal midline. Identification of these factors should yield insights into cross-talk between the AP and DV patterning systems of the Drosophila blastoderm.

The activity of Opa has previously been suggested to be concentration-dependent (Swantek and Gergen, 2004). By comparing pair-rule gene expression in embryos with varying levels of Opa activity, we found evidence that different enhancers show different sensitivity to the concentration of Opa in a nucleus, explaining why different Opa-dependent regulatory events happen at slightly different times in wild-type embryos.

One of the earliest responses to Opa regulatory activity is the appearance of the slp primary stripes. However, we note that while Opa may contribute to their timely activation, these stripes still emerge in opa null mutant embryos. This is not surprising, as the slp locus has been shown to possess multiple partially redundant regulatory elements driving spatially and temporally overlapping expression patterns (Fujioka and Jaynes, 2012). From our own observations, we have found multiple cases where mutation of a particular gene causes the slp primary stripes to be reduced in intensity, but not abolished (data not shown), suggesting that regulatory control of these expression domains is redundant at the trans level as well as at the cis level. Partially redundant enhancers that drive similar patterns, but are not necessarily subject to the same regulatory logic, appear to be very common for developmental transcription factors (Cannavò et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2008; Perry et al., 2011; Staller et al., 2015; Wunderlich et al., 2015).

General regulatory principles of the pair-rule network

By carefully analysing pair-rule gene expression patterns in the light of the experimental literature (Appendix 1), we have clarified our understanding of the regulatory logic responsible for generating them. In particular, we propose significantly revised models for the patterning of odd, slp and runt. Because the structure of a regulatory network determines its dynamics, and its structure is determined by the control logic of its individual components, these subtleties are not merely developmental genetic stamp-collecting. Our reappraisal of the pair-rule gene network allows us to re-evaluate some long-held views about Drosphila blastoderm patterning.

First, pair-rule gene interactions are combinatorially regulated by an extrinsic source of temporal information, something not allowed for by textbook models of the Drosophila segmentation cascade. We have characterised the role of Opa during the 7 stripe to 14 stripe transition, but there may well be other such signals acting earlier or later. Indeed, context-dependent transcription factor activity appears to be very common (Stampfel et al., 2015).

Second, our updated model of the pair-rule network is in many ways simpler than previously thought. While we do introduce the complication of an Opa-dependent network topology, this effectively streamlines the sub-networks that operate early (phase 2) and late (phase 3). At any one time, each pair-rule gene is only regulated by two or three other pair-rule genes. We do not see strong evidence for combinatorial interactions between these inputs (cf. DiNardo and O'Farrell, 1987; Baumgartner and Noll, 1990; Swantek and Gergen, 2004). Instead, pair-rule gene regulatory logic seems invariably to consist of permissive activation by a broadly expressed factor (or factors) that is overridden by precisely positioned repressors (Edgar et al., 1986; Weir et al., 1988). This kind of regulation appears to typify other complex patterning systems, such as the vertebrate neural tube (Briscoe and Small, 2015).

Finally, pair-rule gene cross-regulation has traditionally been thought of as a mechanism to stabilise and refine stripe boundaries (e.g. Edgar et al., 1989; Schroeder et al., 2011). Consistent with this function, as well as with the observed digitisation of gene expression observed at gastrulation (Baumgartner and Noll, 1990; Pisarev et al., 2009), we find that the late network contains a number of mutually repressive interactions (Eve/Runt, Eve/Slp, Ftz/Slp, Odd/Runt, Odd/Slp, and perhaps Odd/Prd). However, the early network does not appear to utilise these switch-like interactions, but is instead characterised by unidirectional repression (e.g. of ftz and odd by Eve and Hairy, or of runt by Odd). Interestingly, pair-rule gene expression during cellularisation has been observed to be unexpectedly dynamic (Keränen et al., 2006; Surkova et al., 2008), something that is notable given the oscillatory expression of pair-rule gene orthologs in short germ arthropods (Sarrazin et al., 2012; El-Sherif et al., 2012; Brena and Akam, 2013).

Why do pair-rule genes show a late phase of expression?

We have shown that for the pair-rule genes, the transition to single-segment periodicity is mediated by substantial re-wiring of regulatory interactions. In addition, we have shown that this re-wiring is controlled by the same signal, Opa, that activates segment-polarity gene expression. We propose that Opa's effective role is to usher in a 'segment-polarity phase' of expression, in which both canonical segment-polarity factors, and erstwhile pair-rule factors, work together to define cell states. This hypothesis is consistent with the spatial patterns and regulatory logic of late pair-rule gene expression: most pair-rule genes become expressed in narrow segmental stripes, and partake in switch-like regulatory interactions consistent with segment-polarity roles. Furthermore, regulatory feedback from segment-polarity genes suggests the pair-rule genes become integrated into the segment-polarity network: for example, En protein is involved in patterning the late expression of eve, odd, runt and slp (Harding et al., 1986; Mullen and DiNardo, 1995; Klingler and Gergen, 1993; Fujioka et al., 2012).

However, the hypothesis that pair-rule factors perform segment-polarity roles is at odds with that fact that their mutants generally do not exhibit segment-polarity defects. We argue that this discrepancy can be resolved by accounting for partial redundancy with paralogous factors. For example, slp has a closely linked paralog, slp2, expressed almost identically, (Grossniklaus et al., 1992), and simultaneous disruption of both genes is required in order to reveal that the Slp stripes are a critical component of the segment-polarity network (Cadigan et al., 1994a; 1994b). prd and odd also have paralogs, expressed in persistent segmental stripes coincident with their respective phase 3 expression patterns (Baumgartner et al., 1987; Hart et al., 1996). The prd paralog, gsb, gives a segment-polarity phenotype if mutated, but Prd and Gsb are able to substitute for each other if expressed under the control of the other gene's regulatory region (Li and Noll, 1993, 1994; Xue and Noll, 1996), indicating that the same protein can fulfil both pair-rule and segment-polarity functions. Moreover, we have found that a deficiency removing both odd and its closely linked paralogs, sob and drm, gives a cuticle phenotype that shows segment-polarity defects corresponding to the locations of odd secondary stripes, in addition to the pair-rule defects characteristic of odd mutants (data not shown).

We envisage that ancestrally, the orthologs of prd/gsb and odd/sob/drm would have sequentially fulfilled both pair-rule and segment-polarity functions, employing different regulatory logic in each case. Later, these roles would have been divided between different paralogs, leaving the transient segmental patterns of prd and odd as evolutionary relics. Consistent with this hypothesis, the roles of prd and gsb seem to be fulfilled by a single co-ortholog, pairberry1, in grasshoppers, with a second gene, pairberry2, expressed redundantly (Davis et al., 2001).

Therefore, of the four pair-rule factors expressed in segmental patterns after gastrulation (Runt, Odd, Prd, Slp), at least three appear to have segment-polarity functions, although they may perform these roles only transiently before handing over the job to their paralogs. (No function has as yet been assigned to late Runt expression.) Because Hairy expression fades away after phase 2, that leaves only the functions of the late, double-segmental expression patterns of Eve and Ftz to be accounted for. Both these factors partake in the segment-polarity network by repressing slp and wg (Fujioka et al., 2002; Swantek and Gergen, 2004; Copeland et al., 1996). However, unlike canonical segment-polarity factors, their expression fades during germband extension. Functional equivalence with each other explains why, from a patterning perspective, they need not be expressed in every segment. Functional redundancy with En (Fujioka et al., 2012) explains why they need not be persistently expressed (indeed, En is the factor responsible for switching off late eve expression [Harding et al., 1986]). Given that eve shows a phase of single-segment periodicity in many pair-rule insects (Patel et al., 1994; Binner and Sander, 1997; Rosenberg et al., 2014; Mito et al., 2007), (although not in Bombyx mori [Nakao, 2010]), it will be interesting to investigate whether a loss of regular segmental eve expression in the lineage leading to Drosophila is associated with changes to the roles of Ftz (and/or its cofactor, Ftz-F1) in segment patterning (Heffer et al., 2013, 2011).

Is the role of Opa conserved?

In light of our data, it will be interesting to characterise the role of Opa in other arthropod model organisms. The best studied short germ insect is the beetle Tribolium castaneum, which also exhibits pair-rule patterning. An RNAi screen of pair-rule gene orthologs reported no segmentation phenotype for opa knock-down, and concluded that opa does not function as a pair-rule gene in Tribolium (Choe et al., 2006). However, the authors also state that opa knock-down caused high levels of lethality and most embryos did not complete development, indicating that this conclusion may be premature. In contrast to this study, iBeetle-Base (Dönitz et al., 2015) reports a segmentation phenotype for opa knock-down (TC number: TC010234; iBeetle number: iB_04791). The affected cuticles show a reduced number of segments including the loss of the mesothorax (T2). This could indicate a pair-rule phenotype in which the even-numbered parasegment boundaries are lost, similar to the situation in Drosophila. If true, this suggests that at least some aspects of the role of Opa are conserved between long germ and short germ segmentation.

Material and methods

Drosophila mutants and husbandry

Request a detailed protocolWild-type embryos were Oregon-R. The pair-rule gene mutations used were opa5 (Bloomington stock no. 5334), opa8 (Bloomington stock no. 5335) and ftz11 (gift of Bénédicte Sanson). These mutations were balanced over TM6C Sb Tb twi::lacZ (Bloomington stock no. 7251) to allow homozygous mutant embryos to be easily distinguished. Two to four hours old embryos were collected on apple juice agar plates at 25°C, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min according to standard procedures, and stored at -20°C in methanol until required.

RNA probes

Request a detailed protocolDigoxigenin- (DIG) and fluorescein (FITC)-labelled riboprobes were generated using full-length pair-rule gene cDNAs from the Drosophila gene collection (Stapleton et al., 2002) and either DIG or fluorescein RNA labelling mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The clones used were RE40955 (hairy); MIP30861 (eve); GH02614 (runt); IP01266 (ftz); GH22686 (prd); GH04704 (slp); LD30441 (opa); LD16125 (en); FI07617 (gsb); RE02607 (wg).

Whole mount double fluorescent in situ hybridisation

Request a detailed protocolEmbryos were post-fixed in 4% PFA then washed in PBT (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) prior to hybridisation. Hybridisation was performed at 56°C overnight in hybridisation buffer (50% formamide, 5x SSC, 5x Denhardt’s solution, 100 μ g/ml yeast tRNA, 2.5% w/v dextran sulfate, 0.1% Tween-20), with at least 1 hr of prehybridisation before introducing the probes. Embryos were simultaneously hybridised with one DIG probe and one FITC probe to different segmentation genes. Embryos from mutant crosses were additionally hybridised with a DIG probe to lacZ. Post-hybridisation washes were carried out as in Lauter et al., 2011. Embryos were then incubated in peroxidase-conjugated anti-FITC and alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) diluted 1:4000. Tyramide biotin amplification (TSA biotin kit, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) followed by incubation in streptavidin Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used to visualise the peroxidase signal. A Fast Red reaction (Fast Red tablets, Kem-En-Tec Diagnostics, Taastrup, Denmark) was subsequently used to visualise the AP signal. Embryos were mounted in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (ThermoFisher Scientific) before imaging.

Microscopy and image analysis

Request a detailed protocolEmbryos were imaged on a Leica SP5 Upright confocal microscope, using a 20x objective. For each pairwise combination of probes, a slide of ~100 embryos was visually examined, and around 20 images taken for further analysis. Occasional embryos with severe patterning abnormalities were discounted from analysis. Minor brightness and contrast adjustments were carried out using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012, 2012). Thresholded images were produced using the 'Make Binary' option in Fiji. Our full wild-type dataset of over 600 double channel confocal images is available from the Dryad Digital Repository (Clark and Akam, 2016).

Appendix 1

Regulatory changes between phase 2 and phase 3

In the main text, we presented phenomenological evidence for a change to the regulatory effect of Odd protein on prd transcription at the transition between phase 2 and phase 3. In this Appendix, we analyse the expression of the other six pair-rule genes before and after this transition, with particular focus on the inferred regulatory changes involved in mediating the altered expression patterns of odd, slp, runt and eve. Note that throughout what follows, italicised names (e.g. eve) are used to refer to genes and to the distributions of their transcript, whereas capitalised plain text (e.g. Eve) is used to refer to proteins and their distributions. Note also that primary pair-rule stripes shift anteriorly over the course of cellularisation (Surkova et al., 2008), and protein distributions lag slightly behind transcript distributions due to time delays inherent in protein synthesis and decay. This means that slight gaps tend to be present between the anterior border of a stripe and the transcripts of its anterior repressor (e.g. Appendix 1—figure 1A, Appendix 1—figure 2C), whereas slight overlaps may be seen between the posterior border of a stripe and the transcripts of its posterior repressor (e.g. Appendix 1—figure 1C, Appendix 1—figure 3C).

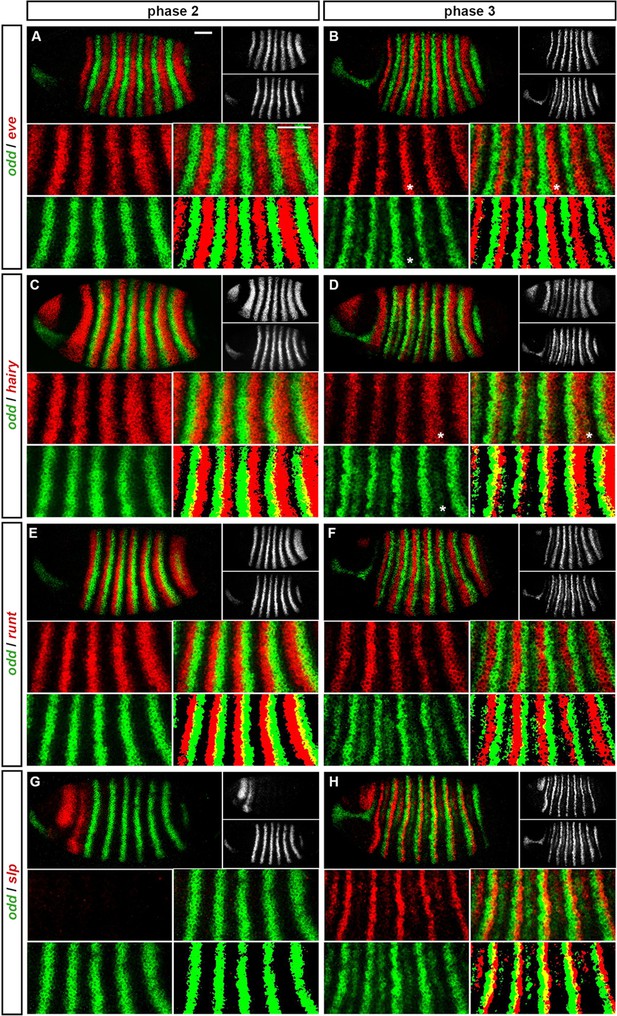

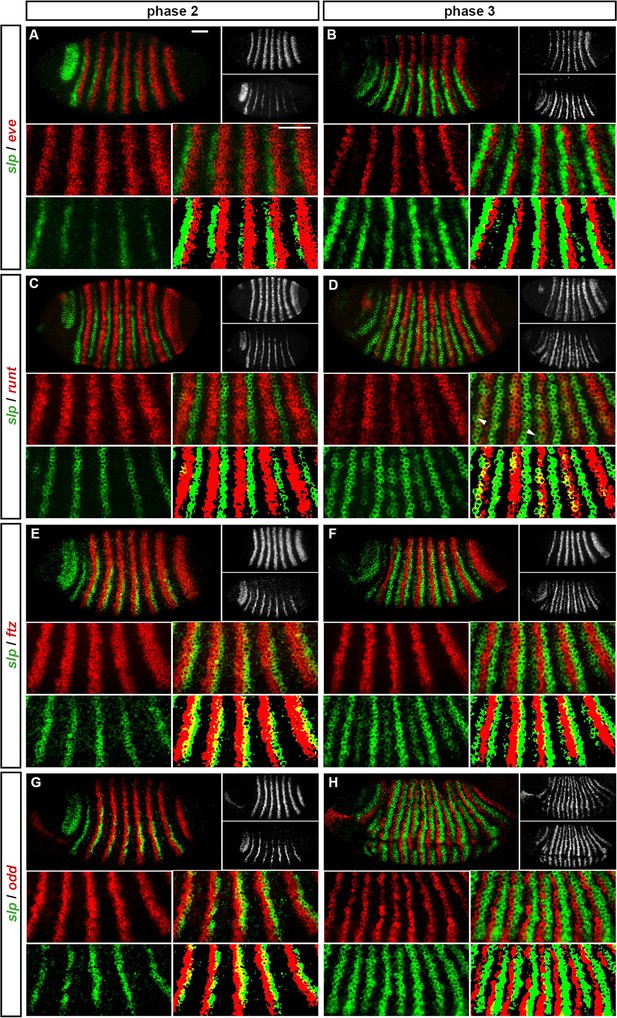

odd-skipped (Appendix 1—figure 1; Appendix 1—figure 1—figure supplement 1)

During phase 2, the primary stripes of odd have anterior boundaries defined by repression by Eve, and posterior boundaries defined by repression by Hairy (Manoukian and Krause, 1992; Jiménez et al., 1996; Appendix 1—figure 1A,C). The primary stripes of odd narrow during phase 3, mainly from the posterior, and secondary stripes intercalate between them. It is not known whether all components of the single-segmental pattern observed at phase 3 are driven by a single enhancer, but we think it likely. The following analysis assumes that primary and secondary stripes of odd are governed by identical regulatory logic during phase 3.

The secondary stripes arise within cells expressing both Eve and Hairy (Appendix 1—figure 1B,D), indicating that repression of odd by these proteins is restricted to phase 2. A loss of repression by Hairy during phase 3 is also supported by increased overlaps between hairy and the odd primary stripes (Appendix 1—figure 1D). The posterior boundaries of the odd secondary stripes appear to be defined by repression by Runt. In wild-type embryos, these boundaries precisely abut the anterior boundaries of the runt primary stripes (Appendix 1—figure 1F), whereas in runt mutant embryos they expand posteriorly (Jaynes and Fujioka, 2004). However, odd is evidently not repressed by Runt during phase 2, because the odd primary stripes overlap with the posterior of the runt stripes (Appendix 1—figure 1E). The anterior boundaries of the odd secondary stripes appear to be defined by repression from Prd (Figure 5D), consistent with the observation that these stripes expand anteriorly in prd mutant embryos (Mullen and DiNardo, 1995). Since the odd primary stripes overlap with prd expression during phase 2 (Figure 5C), it is possible that repression of odd by Prd is restricted to phase 3. However, Prd protein appears relatively late during phase 2 (Pisarev et al., 2009), and Prd protein degradation is upregulated specifically in the region of the odd primary stripes (Raj et al., 2000), suggesting that Prd would have little effect on odd expression during phase 2 either way.

Expression of odd at phase 2 versus phase 3.