Distinct subdivisions of human medial parietal cortex support recollection of people and places

Figures

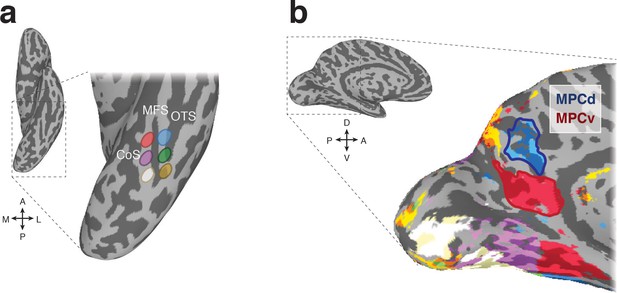

Resting-state functional connectivity seed regions and connectivity-defined regions of interest.

(a) A ventral view of the left hemisphere is shown with the ventral temporal cortex (VTC) highlighted with the dashed-black box, which is enlarged inset. Overlaid onto this enlarged surface are the six anatomically defined regions of interest that divide VTC along both the posterior-anterior and medial-lateral axes with respect to the mid-fusiform sulcus (MFS). The occipitotemporal sulcus (OTC) and collateral sulcus (CoS) are also labeled for reference. (b) A medial view of the left hemisphere is shown with medial parietal cortex (MPC) highlighted by the dashed-black box, which is enlarged inset. Overlaid onto this enlarged surface is the result of the winner-take-all functional connectivity analysis. Colors on the brain correspond to the color of the anatomical ROIs in a. Within MPC, two separate regions are clearly visible. The ventral/posterior region (red-outline) is preferentially connected to anterior medial portions of VTC, whereas the dorsal/anterior region (blue-outline) is preferentially connected to anterior lateral portions of VTC. We define these resting-state ROIs as MPC ventral (MPCv) and MPC dorsal (MPCd), respectively.

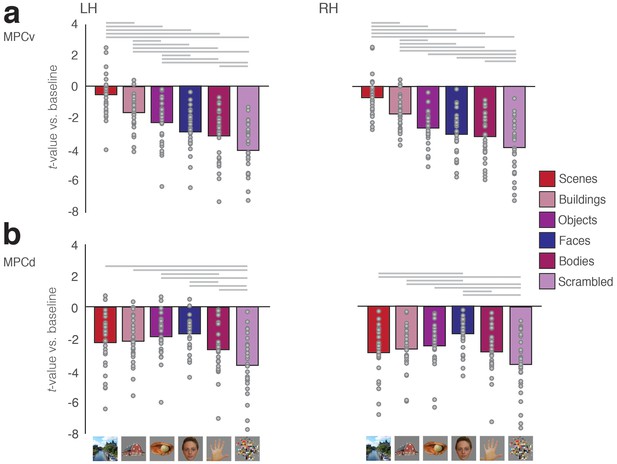

Negative responses in MPC to visually presented stimuli.

(a) Bars represent the mean response magnitude (given by the t-value versus baseline) for all six stimulus categories in MPCv of both hemispheres. These responses have been rank ordered from strongest (i.e. closest to baseline) to weakest. Single participant data points are shown for each category. Gray lines depict pairwise-comparisons that survived Bonferroni correction (p<0.01). The response to scenes was significantly different compared to all other categories in both hemispheres. (b) Bars represent the mean response magnitude for all six stimulus categories in MPCd of both hemispheres. Bars are in the same order as in a, to highlight the different response profiles. Gray lines depict pairwise-comparisons that survived Bonferroni correction (p<0.01). The response to faces was significantly different from the majority of the other categories.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Visually evoked responses in MPCv/MPCd.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.004

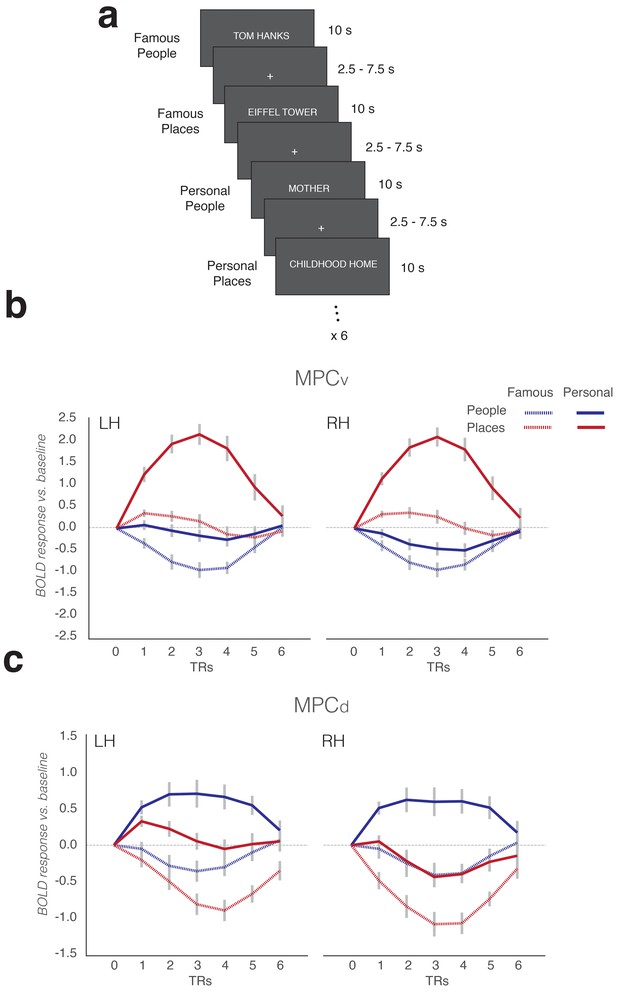

Memory task schematic and average BOLD responses to all conditions in MPC subdivisions.

(a) During the memory task, participants were given trial-wise instructions to recall from memory either famous people, famous places, personally familiar people or personally familiar places, respectively. Participants were asked to visualize the trial target from memory as vividly as possible for the duration of the trial (10 s). Trials were separated by a variable inter-trial-interval (2.5–7.5 s). Participants completed 6 runs of the memory task. Each run contained six randomized trials from each condition. (b) Average response curves from left and right MPCv (relative to baseline) are shown for all conditions in both hemispheres. Response curves were generated by first measuring the average response across the ROI for each trial (6 TR’s from trial onset) and then averaging across trails of the same condition. These responses were then averaged across participants and plotted for each condition separately (Famous people – dashed blue, Famous places – dashed red, Personal people – solid blue and Personal places – solid red). MPCv is maximally recruited during the recall of personal places. The patterns of response are very similar across hemispheres. (c) Same as b, but for MPCd. In contrast to b, MPCd is maximally recruited during the recall of personal people. Again, this pattern is consistent across hemispheres. Response curves were normalized to begin at baseline (zero) for each trial separately. Gray-lines represent the standard error of the mean (sem) across participants for each condition and TR.

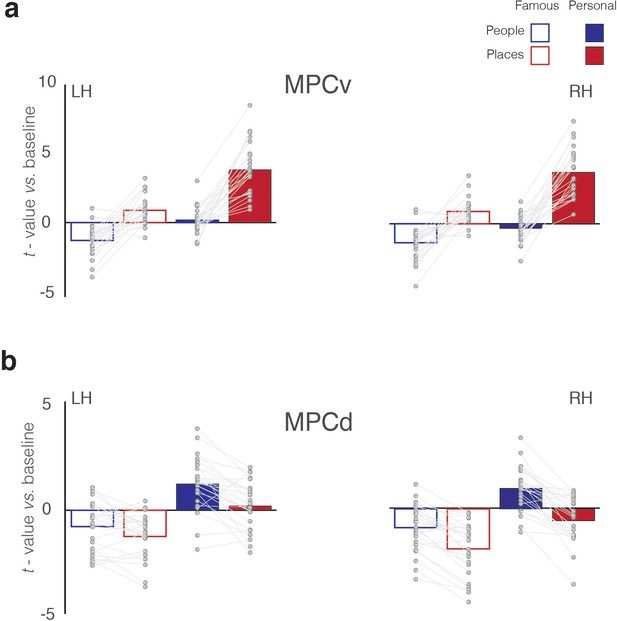

Magnitude of memory recall for all conditions in MPCv and MPCd.

(a) Bars represent the mean response magnitude for each condition (t-value versus baseline) in MPCv of both hemispheres (Famous people – blue open bars, Famous places – red open bars, Personal people – blue closed bars, Personal places – red closed bars). Data points for each participant are connected. In both hemispheres, MPCv is positively recruited during the recall of famous places and personal places, whereas responses during the recall of people (either famous or personal) are largely negative, reflecting a Category preference for places. MPCv also exhibits a familiarity effect and is maximally recruited during the recall of personal places, reflecting the effect of Familiarity. The interaction between Category and Familiarity is also evident. Indeed, there is a larger category difference (places-people) in the personal over famous conditions. (b) Bars represent the mean response magnitude for each condition in MPCd of both hemispheres. Here, MPCd is only positively recruited during recall of personal people, reflecting both a Category preference for people and a Familiarity effect. The interaction between Category and Familiarity is also evident: there is a larger category difference (places-people) in the personal over famous conditions.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Memory recall effects in MPCv/MPCd.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.007

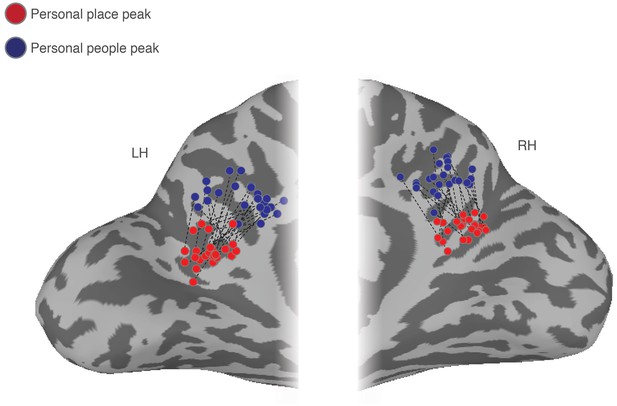

Ventral/posterior – dorsal/anterior shift in peak place memory and peak people memory.

Enlarged partial views of the posterior medial portion of both the left and right hemispheres are shown. Overlaid onto these enlarged surfaces are the locations of the peak responses during recall of personal places (red dots) and recall of personal people (blue dots) for each participant. The corresponding peaks are connected for each participant with a dashed black line. Across participants, there is a consistent ventral/posterior – dorsal/anterior shift in the peak location of memory recall, such that the peak for recall of personal places is never posterior or ventral of the peak for recall of personal people.

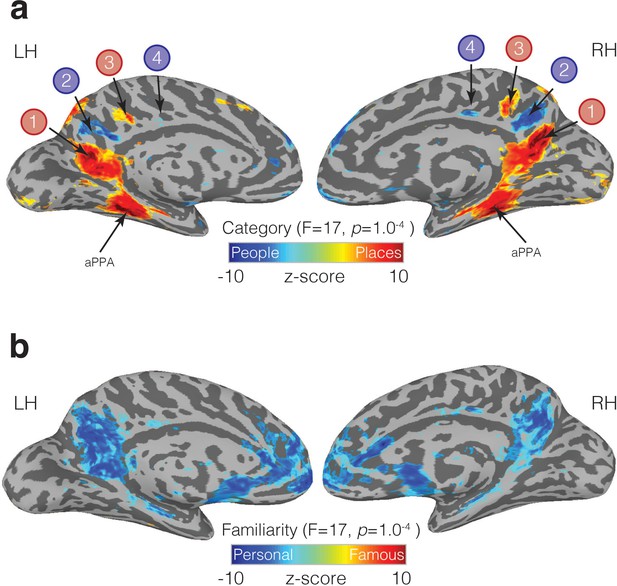

Familiarity and Category-selective recall in MPC.

(a) Medial views of both the left and right hemispheres of a representative participant are shown. Overlaid onto these surfaces is the main effect of Category from the linear-mixed-effects analysis (node-wise p=1.0−4, q = 5.8−4). Cold colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of people (famous and personal), whereas hot colors represent regions of the brain more active during recall of places (famous and personal). An alternating pattern of memory recall is evident within MPC along the ventral/posterior – dorsal/anterior axis. ROIs 1 and 2, correspond largely to our initial resting-state ROIs (MPCv, MPCd), whereas the anterior pair of regions was not defined initially. We also observe significant place recall in aPPA, and some small clusters of significant people recall in anterior cingulate cortex. (b) The same medial views are shown but overlaid is the main effect of Familiarity (node-wise p=1.0−4, q = 5.8−4). Cold colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of personally familiar stimuli (places and people), whereas hot colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of famous stimuli (places or people). A large swath of MPC exhibits an overwhelming Familiarity effect with greater activity during recall of personal over famous stimuli. Familiarity effects were also present in the anterior cingulate cortex, insula and ventral medial prefrontal cortex.

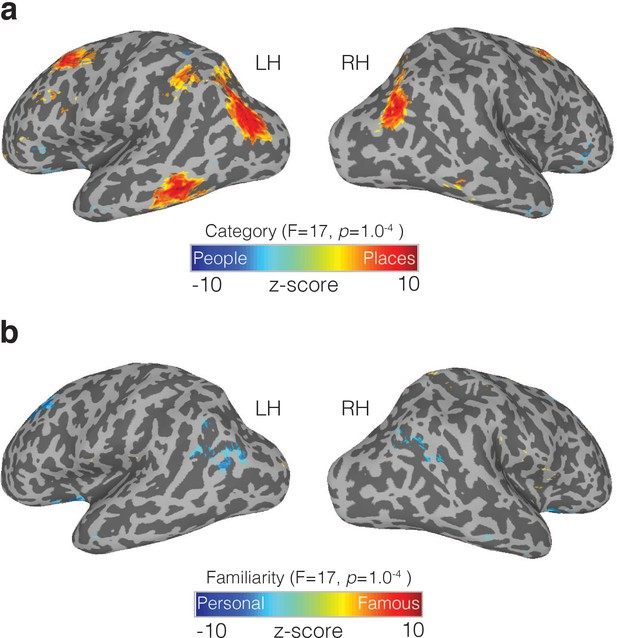

Memory recall effects on the lateral surface.

(a) Lateral views of the left and right hemispheres are shown. Overlaid onto these surfaces is the main effect of Category (p=1.0−4, q = 5.8−4). Cold colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of people (famous and personal), whereas hot colors represent regions of the brain more active during recall of places (famous and personal). Significant responses during place recall were present in the posterior angular gyrus, inferior temporal sulcus and superior frontal regions. In contrast, significant responses to people recall were generally smaller in areal extent but nevertheless present in the insula and anterior temporal regions, particularly in the right hemisphere. (b) Effect of Familiarity (p=1.0−4, q = 5.8−4) overlaid onto the same surfaces. Cold colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of personally familiar stimuli (places and people), whereas hot colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of famous stimuli (places or people). Familiarity effects were present in superior-frontal regions, superior-temporal sulcus and the angular gyrus/caudal inferior parietal lobule.

-

Figure 6—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Memory recall effects in PPA and FFA.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.011

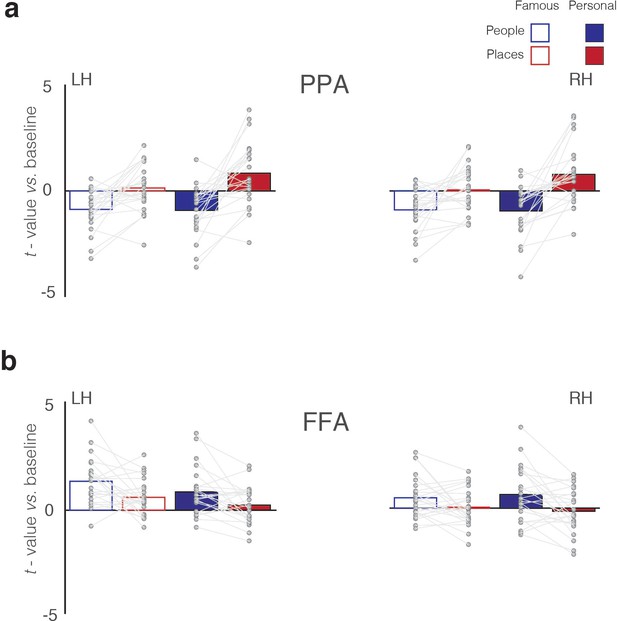

Memory recall effects in PPA and FFA.

(a) Bars represent the mean magnitude of response (t-value versus baseline) for all conditions in PPA of both the left and right hemispheres. Single participant data points and are shown and are connected for each participant. PPA is positively engaged during the recall of famous places and personal places, whereas responses during the recall of people (either famous or personal) are negative, reflecting a Category preference for places. PPA also exhibits a familiarity effect and is maximally engaged during the recall of personal places. The interaction between Category and Familiarity is also evident. Indeed, there is a larger category difference (places-people) in the personal over famous conditions. (b) Same as a, but for FFA in both hemispheres. Unlike PPA, FFA is driven mostly by the recall of people but shows little to no effect of familiarity. Indeed, the response to famous and personal people is largely equivalent.

-

Figure 6—figure supplement 2—source data 1

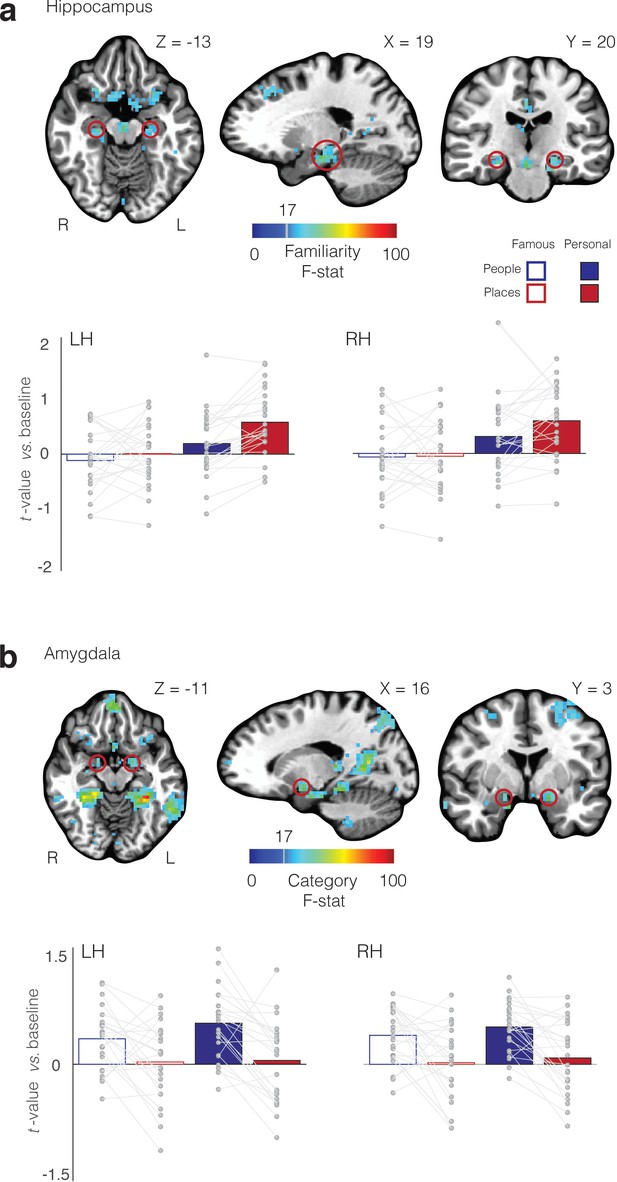

Memory recall effects in Hippocampus and Amygdala.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.013

Memory recall effects in the Hippocampus and Amygdala.

(a) Axial, sagittal and coronal slices are shown. Overlaid onto these slices is the magnitude of the main effect of Familiarity. The red-circles highlight the approximate location of the Hippocampus in both hemispheres. Images are in radiological convention. Bars represent the mean magnitude of response to all conditions (versus baseline) in the Hippocampus of both the left and right hemispheres. Single participant data points and are shown and are connected for each participant. In both hemispheres, the Hippocampus shows larger positive responses on average during the recall of places over people, as well as, a familiarity effect with larger responses during recall of personal over famous stimuli. (b) Axial, sagittal and coronal slices are shown. Overlaid onto these slices is the magnitude of the main effect of Category. The red-circles highlight the approximate location of the Amygdala in both hemispheres. Images are in radiological convention. Bars represent the mean magnitude of response to all conditions (versus baseline) in the Amygdala of both the left and right hemispheres. Unlike the Hippocampus, the Amygdala shows only the effect of Category with positive responses to the recall of famous and personal people, but little to no effect of Familiarity.

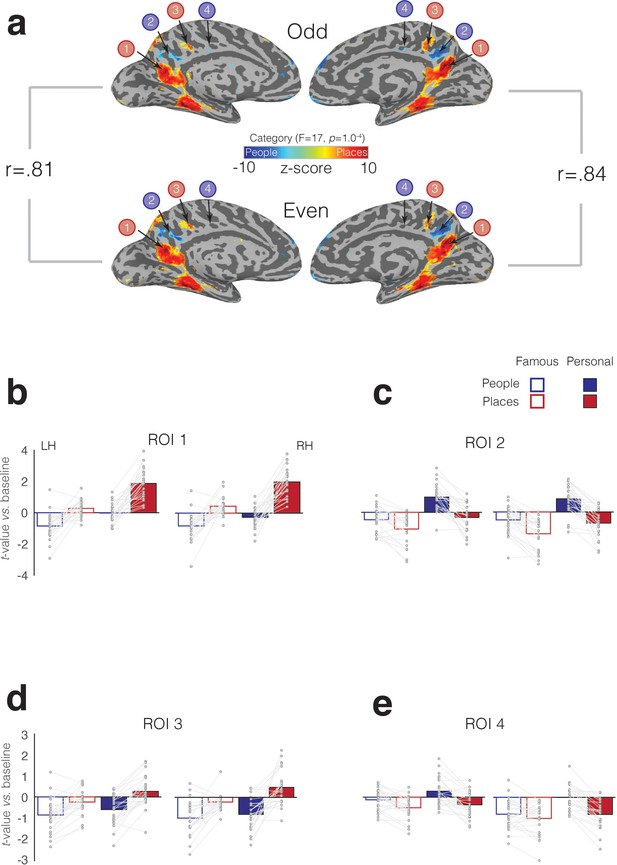

Split-half analysis and memory recall effects in four MPC subdivisions.

(a) The effect of Category (node-wise p=1.0−4, q = 5.8−4) is overlaid onto medial views of both the left and right hemispheres for both independent halves of the data separately (Odd – top row, Even – bottom row). Cold colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of people, whereas hot colors represent regions of the brain more active during recall of places. Despite having half the amount of data, the alternating pattern of category-selectivity within MPC is present in both halves and hemispheres, respectively. The magnitude of the category effect (F-stat) was highly correlated across splits. The reported rho-values correspond to the correlation of the node-wise F-statistic for the effect of category in each hemisphere across the two splits. (B) Bars represent the mean response magnitude for each condition (t-value versus baseline) from ROI 1. Single participant data points are shown and are connected for each participant. (c-e) same as (a), but for ROIs 2–4.

-

Figure 7—source data 1

Split-half analysis and memory recall effects in four MPC subdivisions.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.018

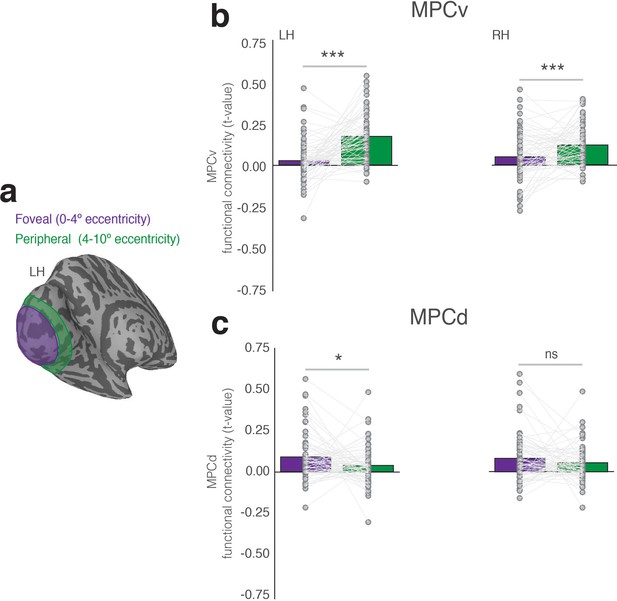

Functional connectivity between MPC subdivisions and foveal/peripheral early visual cortex.

(a) A posterior-medial view of the left hemisphere is shown with the foveal (purple) and peripheral (green) portions of early visual cortex highlighted. (b) Bars represent the average functional connectivity between MPC places and both eccentricity representations in both hemispheres. Single participant data points and are shown and are connected for each participant. As predicted, MPC places shows on average stronger functional connectivity with peripheral over foveal portions of early visual cortex. (c) same as (b), but for MPC people. In contrast, MPC people shows on average stronger functional connectivity with foveal over peripheral portions of early visual cortex. ns = p > 0.05, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

-

Figure 7—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Functional connectiviy values between MPC subdivisions and foveal/peripheral early visual cortex.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.017

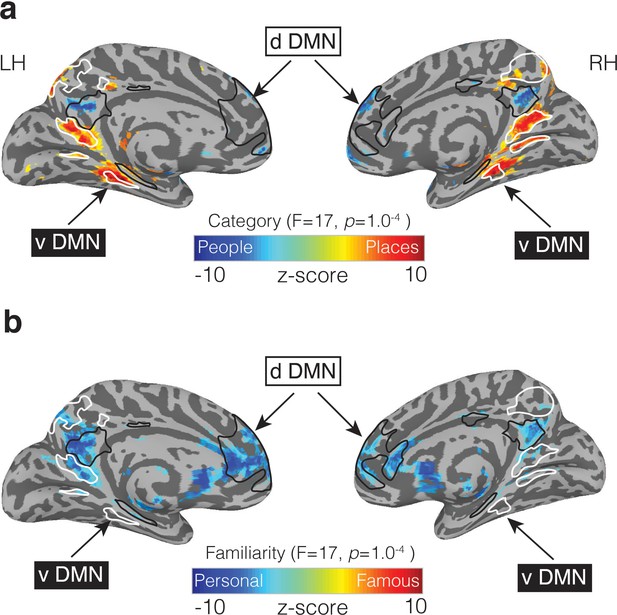

People and Place memory areas of MPC correspond to the dorsal and ventral DMN subnetworks.

(a) Medial views of both the left and right hemispheres are shown (TT n27 surface). Overlaid onto these surfaces is the effect of Category (p=1.0−4, q = 5.8−4). Cold colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of people (famous and personal), whereas hot colors represent regions of the brain more active during recall of places (famous and personal). Masks of the dorsal DMN (dDMN) are outlined in black and show a striking spatial correspondence to regions more active during recall of people. In contrast, masks of the ventral DMN (vDMN) are outlined in white and correspond to regions more active during recall of places. DMN masks were taken from 38. (b) The effect of Familiarity is overlaid onto the same surfaces (p=1.0−4, q = 5.8−4). Cold colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of personally familiar stimuli (places and people), whereas hot colors represent regions of the brain more active during the recall of famous stimuli (places or people). Unlike in (a), regions showing a Familiarity effect overlap with regions from both the dDMN and vDMN.

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Full statistical breakdown of behavioral and functional data.

Supplementary file 1a: Statistical analysis of behavioral responses collected directly after the memory experiment. Data are provided for both subjective vividness and the proportion of missed trials. Table includes F-values, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. In each case, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted with Category (Places, People) and Familiarity (Famous, Personal) as within-participant factors. In the case of vividness ratings, both main effects of Category and Familiarity were significant, reflecting on average higher vividness ratings for the recall of people over places and for personal over famous stimuli. The significant Category by Familiarity interaction reflects a larger familiarity difference (Personal >Famous) during recall of places over people. For the proportion of missed trials, neither main effect was significant, but their interaction was. This interaction is driven by more missed trials for famous places than people, but fewer missed trials for personal scenes than people. Supplementary file 1b: Statistical analysis of memory effects in MPCv and MPCd. Table includes Fvalues, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. MPCv showed significant main effects of Category, Familiarity and Hemisphere. These were qualified by a significant three-way interaction, reflecting a larger familiarity difference (Personal >Famous) between categories (Places > People) in the right over left hemisphere. MPCd also showed significant main effects but did not show a significant three-way interaction. Importantly, however, MPCd did show the predicted Category by Familiarity interaction, which reflects a larger familiarity difference for the recall of people over places. Supplementary file 1c: Statistical analysis of memory effects in ROI 1. Table includes Fvalues, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. ROI one showed significant main effects of Category, Familiarity and Hemisphere. These were qualified by a significant three-way interaction, reflecting a larger familiarity difference (Personal >Famous) between categories (Places > People) in the right over left hemisphere. Supplementary file 1d: Statistical analysis of memory effects in ROI 2. Table includes Fvalues, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. ROI two showed significant main effects of Category, Familiarity and Hemisphere, but did not show a significant three-way interaction. Importantly, however, ROI two did show the predicted Category by Familiarity interaction, which reflects a larger familiarity difference for the recall of people over places. Supplementary file 1e: Statistical analysis of memory effects in ROI 3. Table includes Fvalues, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. ROI three showed significant main effects of Category, Familiarity, but not Hemisphere. Although ROI three did not show a significant three-way interaction, ROI three did show the predicted Category by Familiarity interaction, which reflects a larger familiarity difference for the recall of places over people. Supplementary file 1f: Statistical analysis of memory effects in ROI 4. Table includes Fvalues, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. ROI four showed significant main effects of Category, Familiarity and Hemisphere. These were qualified by a significant three-way interaction, reflecting a larger familiarity difference (Personal >Famous) between categories (People > Places) in the right over left hemisphere. Supplementary file 1g: Statistical analysis of memory effects in PPA and FFA. Table includes Fvalues, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. PPA showed significant main effects of Category and Familiarity, but not Hemisphere. PPA only showed a significant Category by Familiarity interaction, reflecting a larger familiarity difference (Personal >Famous) between categories (Places > People) with no clear difference between hemispheres. In contrast, FFA showed significant main effects of Category and Hemisphere, but not Familiarity. These were qualified by a significant three-way interaction, which reflects the presence of category and familiarity in the left hemisphere, but only the effect of category in the right hemisphere. Supplementary file 1h: Statistical analysis of memory effects in the Hippocampus and Amygdala Table includes Fvalues, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. The Hippocampus showed significant main effects of Category and Familiarity, but not Hemisphere. Only the Category by Hemisphere interaction was significant. The Amygdala showed only a significant effect of Category, with larger responses for the recall of people irrespective of the level of familiarity. Supplementary file 1i: Statistical analysis of the resting-state functional connectivity between MPCv, MPCd and Foveal, Peripheral portions of early visual cortex (EVC). Table includes F-values, degrees of freedom (df), p-values and estimates of effect size using partial eta squared. The main effects of ROI and Hemisphere were not significant, but the main effect of Eccentricity was reflecting on average stringer connectivity with peripheral than foveal portions of EVC. These were qualified however by a significant three-way interaction, reflecting on average stronger connectivity between MPCv and peripheral EVC, but stronger connectivity between MPCd and foveal EVC in the left over right hemispheres.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.020

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.47391.021