Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity modulates the moment-to-moment probability of reward-related self-timed movements

Peer review process

This article was accepted for publication as part of eLife's original publishing model.

History

- Version of Record updated

- Version of Record published

- Accepted Manuscript published

- Accepted

- Received

- Preprint posted

Decision letter

-

Jesse H GoldbergReviewing Editor; Cornell University, United States

-

Kate M WassumSenior Editor; University of California, Los Angeles, United States

-

Jesse H GoldbergReviewer; Cornell University, United States

In the interests of transparency, eLife publishes the most substantive revision requests and the accompanying author responses.

Decision letter after peer review:

[Editors’ note: the authors submitted for reconsideration following the decision after peer review. What follows is the decision letter after the first round of review.]

Thank you for submitting your work entitled "Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity controls the moment-to-moment decision of when to move" for consideration by eLife. Your article has been reviewed by 3 peer reviewers, including Jesse H Goldberg as the Reviewing Editor and Reviewer #1, and the evaluation has been overseen by a Senior Editor.

Our decision has been reached after consultation between the reviewers. Based on these discussions and the individual reviews below, we regret to inform you that your work will not be considered further for publication in eLife.

All three reviewers appreciated the potential novelty that even baseline dopamine levels could be predictive under the task conditions of when the animal will move. However, as detailed in the reviews below, there were critical concerns regarding the animal's performance in the task, the novelty of pre-movement dopamine ramps relative to prior work, and the single-trial analyses which were not sufficient to convincingly demonstrate that ramps did not result from artifact of averaging across trials with different event timing. Ultimately, it was determined that even if the authors addressed the relationship between ramps and movement on single trials, issues with the behavioral performance and task design make it difficult to infer how signals correspond to internal processes such as reward anticipation, RPE, behavioral inhibition, or – as the manuscript suggests – timing.

Reviewer #1:

Hamilos et al. image DA axonal and neuronal CA signals in mice engaged in a self-timed lick task. They observed a ramping signal prior to lick onset that could predict, on average when a mouse would lick. While ramps in DA Ca signals have been observed as animals locomote towards known rewards (e.g. Howe et al., Hamid et al., Mohebi et al., all cited) and while DA activity is known to exhibit correlations with movement onsets – what's new and potentially important in this paper is how well the DA ramps could predict movement onset time – even on single trials. Complementing this finding were causal experiments where photoactivation or inhibition on single trials could promote or delay movement initiation. Given the amount of effort invested into the relationship between DA activity and upcoming movements – it is surprising that the strong correlation between the DA ramp and movement initiation (or decision, see discussion of Guru et al., paper below) hasn't been so clearly observed before (to my knowledge). This paper links DA activity to the timing of a reward-related decision extremely well.

Figure 3 of Guru et al. (unpublished biorxiv paper from Warden lab, not cited) shows a similar result as this paper except the internally timed action is not to produce movement but rather to terminate movement (stop running on a wheel). The fact that the same ramp is observed in both of these conditions undermines the connection that the authors make about ramping DA and decision to move. Taken together, it seems the DA ramps are more about the timing of a self-paced decision (whether it be to start or to stop doing something) than about movement initiation. The authors may want to re-tweak the interpretations of this paper to allow for this more general perspective.

Reviewer #2:

In this study Hamilos and colleagues measured dopamine signals in mice performing a self-timing task. They took advantage of the variability in the first lick time to study how dopamine signaling preceding the first lick varied with the timing of the first lick. While a number of studies have reported short-latency (<500 ms) increases in dopamine activity immediately preceding movements, the authors make a number of novel findings. First, dopamine photometry signals ramped up over several seconds preceding the first lick. Second, the steepness of this ramping, even the amount of baseline signal predicted the first lick time. Third, optogenetic activation and inhibition reduced or increased the first lick time. The authors are commended for performing several different types of photometry experiments. The authors conclude that dopaminergic signals unfolding over seconds control the timing of movements, but not as much the ability to move itself. While the work is novel and adds an interesting perspective on the function of dopaminergic neurons, there were concerns about some of the evidence for the first two claims, as well as insufficient detail in some of the statistical analysis that make it difficult to fully judge the paper's merits. The main concerns are detailed below.

1. Lines 151-153: "we observed systematic differences in the steepness of ramping that were highly predictive of movement timing (Figure 1D-E)." The reviewer agrees this is quite evident from the ramping curves, but still the authors should formally show the fact that the steepness (i.e., slope) of ramping is predictive of timing. The decoding model in Figure 6 goes some way toward this goal, but it seems Figure 6 uses time to threshold rather than the slope. It would be worthwhile to check in Figure 1 or Figure 2 whether the time to first lick is negatively correlated with slope of ramping.

2. Figure 4: similar to the previous comment. The reviewer found it difficult to interpret Figure 4 and suggests including a more traditional analysis, such as a Pearson correlation between the time to first lick and the level of pre-cue baseline dopamine.

3. Figure 6: the reviewer was confused about the contribution of the pre-cue baseline signal (predictor # 7) to the nested model. From the results in Figure 6B and 6C it appears that the pre-cue signal has almost zero contribution to the model (it was the only predictor with a non-significant weight in 6B). But this seems to contradict the authors' claim that "higher pre-cue, baseline DAN signals are correlated with earlier self-timed movements." If baseline signals do indeed correlate with timing of movements, shouldn't the weight of predictor # 7 be higher? This reviewer may have misunderstood some important detail, so some clarification of this issue in the text would be helpful. The reviewer also requests clarification of the difference between the "offset" (Predictor # 0) and "pre-cue" (Predictor # 7) as they both seem to be referring to some sort of baseline signal.

4. In several figure panels (including 6B, 7C, 7D) stats are either missing or details are too sparse to fully evaluate the significance of the results. The authors are requested to include information about sample size, type of test used, and if possible the exact p value.

Reviewer #3:

Assad and colleagues examined nigrostriatal dopamine signals in head-fixed mice performing a licking task. Reward was available if mice first withheld licking for several seconds after a cue. They observed a ramping increase in dopamine before the time of first lick, that stretched in proportion with this hold interval. Optogenetic increases/decreases of dopamine caused licking to be earlier/later. They conclude that dopamine ramps are involved in controlling the timing of movements.

There are several interesting aspects of this work, including the comparison between different DA signals (Figure 2) and the ramps themselves. Based on prior work in the field I have no problem believing most of the title "…dopaminergic activity controls the moment-to-moment decision of when to move". The problem is that the aspects of this work that are novel are either not well supported by data, or rely on questionable analyses and interpretations. There are also serious problems with the behavioral task and the quality of some recordings.

Main points:

1) The mice are notably bad at the behavioral task. Based on Figure 1B it is rare for them to wait long enough to get the reward. They do wait longer in the 5s condition compared to 3.3s, just not long enough. This general inability to perform the task casts further doubt on what internal representations might be driving dopamine signals and behavior. I'm not sure it's reasonable to describe the behavior as "timing", if the timing is usually wrong. And given that they see the same ramps before spontaneous licks outside the task, the task seems largely irrelevant.

2) Optogenetic manipulation of dopamine made movements more or less likely, as expected from prior studies. But the authors claim more than this – that the optogenetic 'effects were expressed through a "higher-level" process related to the self-timing of movement'. I did not find this claim convincing, even beyond the issue that the mice are very poor at timing. If an action is prepotent in a given behavioral context as the result of training, then increasing dopamine may increase the likelihood of that action being emitted. Giving even more dopamine (higher laser power) may lower the threshold for *any* action being emitted. But this doesn't demonstrate anything much about timing per se.

3) A key claim is that the dopamine signals are "slowly-evolving". This makes it essential to define "slow". In the dopamine field "slow" or "tonic" has often been used to referred to microdialysis signals presumed to change over tens of minutes. Here the authors describe ramping processes that may complete over several seconds, or be done in less than a second. So the kinetics of the signal seem more linked to the (varying) speed of behavioral transitions than to any inherently "slow" process.

4) Furthermore, in the Discussion the authors describe the instantaneous state of the dopamine signal at trial onset as "tonic", which seems like a mistake: they demonstrate that this signal has been immediately "reset" and cares more about the upcoming behavior than the immediately preceding trial just a few seconds earlier. This is not how "tonic" is used in the dopamine literature (e.g. Niv/Daw/Dayan describing tonic dopamine as integrating reward rate over prior recent trials).

5) The ramp-like pattern is interesting and may indeed be comparable to dopamine ramps previously reported in other tasks. But ramps can arise as an artifact of averaging across trials in which events have different timing. To avoid this problem the authors examined single-trials (Figure 6). But the analysis employed does not actually measure ramping on single trials. Instead, they examine the timing of crossing an artificial threshold, and they see that this threshold crossing time predicts lick time well when the threshold is high. This seems equivalent to noting that dopamine increases shortly before licking, which we already knew from movement-aligned averages; it doesn't seem to demonstrate the point the authors wish to make.

6) The authors note correctly that the signals they observe "could reflect the superposition of dopaminergic responses to multiple task events, including the cue, lick, ongoing spurious body movements, and hidden cognitive processes like timing." But I wasn't convinced that the regression models provided much insight into those hidden processes. Adding a "stretch" parameter felt merely like a descriptive fit to the observed data than a process-based model.

7) It is not uncommon to see neural activity evolving between cues and movements in a manner that scales with the interval between these events (e.g. Renoult et al. 2006, Time is a rubberband: neuronal activity in monkey motor cortex in relation to time estimation). It is interesting that dopamine can do something similar, but that doesn't seem to support a special role for dopamine.

8) The figures are not well organized at all. Figs1 and 2 seem partly redundant, and are often referred to together. Figure 3 is mentioned only in passing to say that an accelerometer was present, without describing the Figure 3 results or why they are important (perhaps should be a supplemental figure after clarification).

9) line234: "(highest S:N sessions plotted for clarity, 4 mice, 4-5 sessions/mouse, 17 total)". This seems weird and concerning. If signals were good enough to use for other analyses, why not this one?

10) Fig6, what does it mean that the tdt (control) signal is also a significant predictor of first-lick time? This seems like a serious problem for a control signal.

[Editors’ note: further revisions were suggested prior to acceptance, as described below.]

Thank you for choosing to send your work entitled "Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity controls the moment-to-moment decision of when to move" for consideration at eLife. Your letter of appeal has been considered by a Senior Editor and a Reviewing editor, and we are prepared to consider a revised submission with no guarantees of acceptance.

This resubmission may go back to all of the same and/or new reviewers. To ensure your revision has the best chance possible, we encourage you to well address each of the prior concerns in both the manuscript and in the response to review. Below are a few key concerns that we think are especially important for you to address.

1. It will be key to nail down the legitimacy of the claim that dopamine ramps and amplitudes at movement onsets on single trials. The main concerns (points 1-4) of R2 and point 5 of R3 well-articulate this concern.

2. Well justify and better explain the task (as was partly done in the appeal). The idea of the dopamine signal as playing any role in 'timing' was problematic because there was not a stringent control that timing was necessary in the task.

We encourage you to clarify that the task was not designed to specifically rule in or out the many models of what dopamine encodes and rather clarify that the goal of the study is to identify dopamine relationship to upcoming movements or behavioral transitions. Fully addressing R3 comment 1 is necessary.

We also encourage you to address the statement that ramps existed before licks outside the task, which shows the irrelevance of the task for the finding. Showing examples of this phenomenon might help. And we encourage you to consider how this finding relates to the central claim of 'timing.'

Please be aware that the revision requirements outlined above, along with your response to these comments, will be published should your article be accepted for publication, subject to author approval. In this event you acknowledge and agree that the these will be published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license.

[Editors’ note: further revisions were suggested prior to acceptance, as described below.]

Thank you for resubmitting your article "Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity modulates the moment-to-moment probability of movement initiation." for consideration by eLife. Your revised article has been reviewed by 3 peer reviewers, including Jesse H Goldberg as the Reviewing Editor and Reviewer #1, and the evaluation has been overseen by Kate Wassum as the Senior Editor.

The reviewers have discussed their reviews with one another, and the Reviewing Editor has drafted this to help you prepare a revised submission.

Essential revisions:

1) Please address this concern regarding 'baseline" predictors: The authors have made significant improvements in describing the task, but there remained a lack of information about behavior in the lamp-off period before the cue was turned on (the baseline). The main concern is that this delay period is technically not a baseline because the lamp-off serves as an additional predictive cue. The authors tried to prevent this by randomizing the delay time (0.4-1.5 s), but this range looks comparable or even smaller than the variability in first-lick time shown in Figure 2B. They also did a control experiment without a lamp and showed qualitatively similar performance, but I didn't find the data very convincing (for some reason the data shown in figure supplement 1C does not have clear peaks at 3.3 s). Knowing whether this is a real baseline is important because the authors set cue-on as t=0, and do not consider behavior prior to that. This would not be a big concern if the authors can show that there is no statistically significant relationship between the lamp-off to cue-on delay and the lick onset on that trial. Otherwise, the concern is that their finding that higher baseline fluorescence predicts earlier licks may have a trivial explanation.

2) Address comments re: Figure 7, where there is still some confusion about the description of the sample size. For example, line 339 lists 12 mice but I think the correct variable is number of trials. The text should thus include the size of the actual variable used in the plots (listing the number of mice as well is ok, but this is not sufficient on its own). Furthermore, the results would more convincing if this figure included single-animal comparisons rather than just pooled data or across-session comparisons. Basically, could the authors please include a panel similar in style to Figure 7C but where individual points represent single animals, not sessions? This would be more consistent with other optogenetic-behavioral studies in rodents.

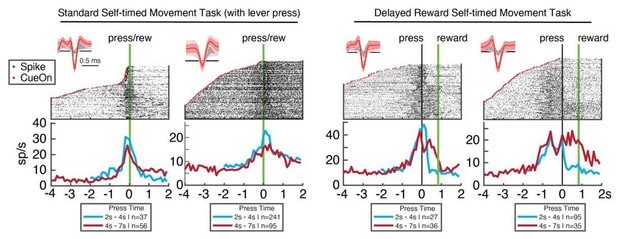

3) Please better address an issue with interpretation of results, specifically regarding movement timing versus reward expectation: The authors claim that their results mean a causal role for the level of dopamine ramps in modulating the probability of action initiation, but that interpretation seems strange given that these ramps are often observed when animals are already moving (Howe et al., 2013; Hamid et al., 2016; Engelhard et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Guru et al., 2020). In common with all these papers, dopamine ramps seem to be related to the temporal prediction of when reward will be available. This was shown nicely by Kim et al., 2020, where they showed that regardless of the movements performed by the mice, ramps are elicited in relation to when the animal expects the rewards to arrive (see especially their moving bar experiments). In the present work, this interpretation is also consistent with the results (and more consistent with previous works): when animals decide to move early, the DA system receives this information and that results in a more steeply rising ramp, while when animals decide to move late, the same thing occurs, and the ramp rises more slowly. The issue at hand is that the initiation of movement (licking) is strongly correlated with reward delivery (or with the time of expected reward delivery in case of failed trials) and thus it is not possible to distinguish between these interpretations. So, in summary, the authors should address the concern that the interpretation of dopamine ramps modulating the moment-to-moment probability of action initiation is unwarranted. Results should be reframed to make it clear that this claim cannot be supported given the possible alternative explanations (such as the one suggesting that DA ramps reflect a prediction of the time of upcoming reward delivery, which is more consistent with the previous literature).

Alternatively, if the authors can find an experimental way to dissociate the expected time for reward delivery from the moment of action initiation, then that would be one way to make a decisive conclusion. For example, the water dispensation could occur at a fixed time relative to the cue – even as the mouse can initiate licking whenever it wants. If DA dynamics still predict initiation time, then the authors' perspective is supported. Yet if the DA dynamics no longer predict initiation time, and instead simply ramp to the reward time, then reviewer 4's perspective is supported. Either result would be interesting. Performing these experiments would be ideal, but not necessary for publication. If the authors do not wish to conduct new experiments along these lines, they should – throughout the manuscript – modify their text to include this alternative interpretation (reward expectation) – or offer in rebuttal a convincing argument as to why the logic of reviewer 4's (and the BRE's) thinking is not sound.

[Editors’ note: further revisions were suggested prior to acceptance, as described below.]

Thank you for submitting your article "Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity modulates the moment-to-moment probability of movement initiation." for consideration by eLife. Your article has been reviewed by 3 peer reviewers, including Jesse H Goldberg as the Reviewing Editor and Reviewer #1, and the evaluation has been overseen by Kate Wassum as the Senior Editor.

The reviewers have discussed their reviews with one another, and the Reviewing Editor has drafted this to help you prepare a revised submission.

Essential revisions:

1) 2/3 reviewers were not persuaded by the author's rebuttal arguments that DA ramps reflect movement initiation and not reward expectation, resulting in an enduring concern that the main message of the paper, evident even in the title, is not watertight. All reviewers still think the paper's findings are timely and important – so a tempering / adjustment of the claims is a reasonable path forward to publication. The change in 'pitch' of this paper would need to include changes to title, abstract, and discussion. While some specific recommendations are included in the full reviews pasted below, the authors are in the best position to truly internalize reviewer's four's sound arguments to transform the message of the paper into one that allows for reward expectation to be the variable that DA ramps reflect, that optogenetic experiments manipulate, and that ultimately affects movement timing.

If you have not already done so, please ensure that your manuscript complies with eLife's policies for statistical reporting: https://reviewer.elifesciences.org/author-guide/full "Report exact p-values wherever possible alongside the summary statistics and 95% confidence intervals. These should be reported for all key questions and not only when the p-value is less than 0.05."

Reviewer #1:

I am satisfied with the responses to points 1 and 2.

I am not completely persuaded by the author's arguments in revision point 3. First, their argument starts with the statement that "dopamine ramps have not, in fact, been observed in relation to passive temporal expectation of reward – except when some kind of external sensory indicator of proximity to reward was provided." They further argue that DA ramps have not been observed in Pavlovian conditioning – citing many classic Schults papers and more recent rodent work. But Figure 3b of Fiorillo, Tobler, Schultz, Science 2003 clearly shows ramps when rewards are uncertain even in a Pavlovian task. The first section of their argument was based on the absence of ramps in Pavlovian tasks, so this falls apart on scrutiny. There is more going on here than the authors are noting. Also, it's strange that in discussion the authors invoke an 'operant' nature of their task – based on the idea that the animal must move to earn reward. With this definition one wonders what constitutes a non-operant task – even the classic Schultz papers on DA signals during Pavlovial conditioning require tongue extension to retrieve water.

In revision, I recommend the following:

1) In abstract, the word 'controls' (line 20) seems potentially overstated. Please change to 'predicts' or 'is associated with'

2) In Discussion, line 456, I think the authors should include an expanded (~2-3 sentence) consideration that their signals that predict movement are expected value signals – essentially including Rev 4's interpretation as a plausible one.

Overall, this is an important paper suitable for eLife.

Reviewer #2:

The authors have addressed all my comments and I have no further concerns.

Reviewer #4:

I don't find the authors response to my comment satisfactory. Given that the paper title is "Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity modulates the moment-to-moment probability of movement initiation" and that if published as is, this would constitute peer-reviewed evidence that dopamine ramps modulate movement timing, the relationship between the ramps and movement initiation should be ironclad. Yet from the presented data as well as the authors comments, it still seems to me more likely that these ramps represent an internal measure of reward expectation/ expected time of reward delivery. Specifically, the authors state (in bold font) that "dopaminergic ramps have not, in fact, been observed in relation to passive temporal expectation of reward-except when some kind of external sensory indicator of proximity to reward was provided". However, that is not the case, see for example the science paper by Fiorillo, Tobler and Schultz, 2003, as well as their follow-up paper in 2005. Thus, we have evidence that these ramps occur A- when animals are moving (see all the references in my previous comment). B- when animals are not moving and don't intend to, where the time to reward is signaled to them externally (kim et al.). C- When animals are not moving and don't intend to, where the time to reward is not signaled to them externally (Fiorillo et al). D- when animals are not moving but do intend to (present manuscript). Given all these conditions where we see ramping, ascribing them to movement initiation does not seem warranted, especially when we have a parsimonious alternative explanation (Reward expectation).

It may seem at first glance that the optogenetic experiments performed by the authors would counter my point, because they had an effect in modulating the timing of movement initiation. However, these manipulations could just be changing the motivation or reward expectation of the animals, which would make them move earlier or later. The authors agree with this, and then gave the following strange (to me) response: "…reward expectation may be the very force that propels movement in our task. In this view, reward expectation is intrinsically intertwined with movement initiation. Our point is that whatever the dopaminergic signal is tracking, it can be harnessed to influence the probability of movement onset."

This point seems very strange to me because under this view, any type of brain signal related to any external variable that ends up modulating an animal's movement would be ascribed as a movement signal. For example, sensory signals in visual cortex in a perceptual task would be classified as movement initiation signals, because they end up making the animal move (e.g. if we inhibit visual cortex the animals can't perceive the stimulus and won't move correctly). The whole point of claiming that a particular neural signal is related to movement initiation is that it is NOT related to other signals: sensory, reward or others, even as those other variables typically have an end effect of modulating an animal's movement. To take this point further, behavior itself is ultimately about generating movements, and so any behaviorally relevant signal will ultimately affect movements. The authors' claim here is much more specific, and in my view not supported.

To conclude, I'm uncomfortable with the paper keeping its current title and conclusions. It seems to me much more correct to conclude that dopamine ramps reflect reward expectation, and that (of course!) reward expectation can end up influencing movements. This is much more in line with all the previous literature of dopamine and I don't think the authors made a compelling case of abandoning this view. To reiterate what I previously wrote, I do think this is a good paper that should be published, but not under the current framing. I would suggest the following title: "Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity reflects reward expectation and can modulate the moment-to-moment probability of movement initiation". I know it is not as catchy, but I think it's much more correct given what we know, and I don't want to give my stamp of approval to a conclusion which I think is unwarranted.

[Editors’ note: further revisions were suggested prior to acceptance, as described below.]

Thank you for resubmitting your work entitled "Slowly evolving dopaminergic activity modulates the moment-to-moment probability of reward-related self-timed movements" for further consideration by eLife. Your revised article has been evaluated by Kate Wassum (Senior Editor) and a Reviewing Editor.

The manuscript has been improved but there are some remaining issues that need to be addressed, as outlined below:

Your revised manuscript does not fully comply with eLife's requirements for statistical reporting. Please ensure all statistics are included in full in the main manuscript. "Report exact p-values wherever possible alongside the summary statistics and 95% confidence intervals. These should be reported for all key questions and not only when the p-value is less than 0.05." more details can be found here:

https://reviewer.elifesciences.org/author-guide/full

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62583.sa1Author response

[Editors’ note: The authors appealed the original decision. What follows is the authors’ response to the first round of review.]

We will look forward to receiving a revised article and a file describing the changes made in response to the decision and review comments for further consideration.

This resubmission may go back to all of the same and/or new reviewers. To ensure your revision has the best chance possible, we encourage you to well address each of the prior concerns in both the manuscript and in the response to review. Below are a few key concerns that we think are especially important for you to address.

Editor point 1. Well justify and better explain the task (as was partly done in the appeal). The idea of the dopamine signal as playing any role in 'timing' was problematic because there was not a stringent control that timing was necessary in the task.

We addressed this point in our initial appeal, which we reproduce here in case the reviewers didn’t see the appeal. We have added a paragraph to the Results sections of the revised manuscript summarizing these arguments, as well as a new main-text figure (New Manuscript Figure 1) summarizing these results.

Reviewer 3 was critical of the animals’ performance on the self-timed movement task. On reading the reviewer’s comments, we immediately realized that we should have included more discussion of the rich empirical history of timing tasks to contextualize and justify the behavior that we observed in our self-timed movement task. We did not think we had room for this discussion in the manuscript, but this was clearly a mistake! In fact, the behavior of the animals in our specific task was much “better” than the reviewer realized, and our observations were absolutely in line with previous findings in timing tasks. Below, we offer what we believe is overwhelming evidence on this point.

However, before we outline this evidence, we stress that we did not intend to study precise timing behavior. Rather, we set out to determine whether dopaminergic activity could explain when a movement would occur. We focused on self-timed movements, i.e., movements that are not abrupt, temporally-stereotyped reactions to external cues (in contrast to standard stimulus-response paradigms used in the vast majority of studies of the motor system; see Lee and Assad (2003) for discussion of this key distinction). We used self-timed movements as a strategy to induce animals to produce movements with seconds of variability (relative to a reference cue) from trial-to-trial – but we were not overly concerned whether the animal timed “accurately.” In fact, the high degree of variability in movement time from trial-to-trial (from ~1 s to >6 s post-cue) was precisely the handle we needed to address our question: what happens differently in the dopaminergic system when animals move early versus late relative to an initial “reset” cue? If we had omitted the initial cue and allowed the animals to self-initiate movements whenever they pleased, we would not have had a reference to align neural signals, and thus could not have categorized movements as “early” or “late”. Our ability to categorize the movement time relative to the cue allowed us to discover that dopaminergic signals were highly predictive of the movement time. (That is, movement time implies time relative to something.) In this light, early (unrewarded) trials were just as informative as late (rewarded) trials. Thus, the percentage of rewarded trials was not at stake in this manuscript – although we clearly need to explain this logic better.

Nevertheless, there is strong evidence that our animals did, in fact, time well, and their behavior was consistent with the well-established body of findings on timing in animals and humans. We didn’t present this evidence in the original manuscript because we thought it was tangential to our main points and would require too much space. However, we clearly confused the reviewers, so we have addressed these issues in detail in the revised manuscript.

We presume that Reviewer 3 was critical of the task performance because (1) the animals’ movement times were highly variable, and/or (2) the peak of the movement-time distributions preceded the criterion time. We’ll address both issues in turn.

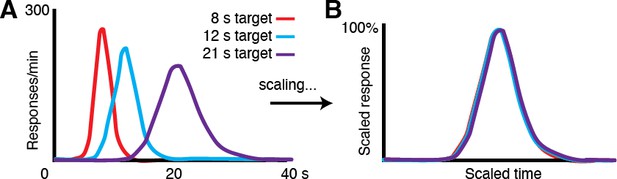

1) Variability in movement time. An observation across timing tasks and species is that the distribution of estimated time intervals has substantial variability. Moreover, that variability (measured by standard deviation) scales proportionally to the length of the timed interval, such that rescaling one interval by the peak time of another will result in overlapping distributions (Author response image 1; human self-timing data). This property is formalized by Weber’s Law (σ = k*T), where the standard deviation of the distribution for a given subject is a product of the subject’s Weber fraction (k, an empirically measured quantity) and the criterion time, T (Gallistel and Gibbon, 2000). The 3.3 s and 5 s task distributions in our task exhibit this scalar property of timing, following Weber’s Law (New Manuscript Figure 1B). This observation alone provides evidence that the animals were timing.

2) Animals’ and humans’ distributions of timed intervals invariably tend to anticipate the criterion interval, even at the expense of reward. The degree to which the distributions anticipate the criterion interval depends on the specific timing task. Most common, time-interval reproduction tasks in animals can be divided into two categories: “peak-procedure” or “differential reinforcement of low response rates” (DRL). Some years ago, our lab introduced a third category into animal studies, “self-timed movement tasks,” which have key features in common with DRL tasks. We will examine these in turn:

Performance in timing tasks follows the scalar property.

(A) Human response-time distributions for three different criterion times, 8, 12 and 21 s (Figure adapted from Allman et al., 2014 (Figures 2 and 3).; data from (Rakitin et al., 1998)). (B) When the distributions in A are scaled by the time of the peaks, they closely overlap, demonstrating the scalar property canonical to timing tasks across species.

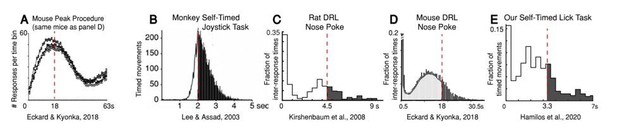

Peak procedure (Author response image 2A): In peak-procedure timing tasks, subjects are allowed to respond as often as they want, but are only rewarded for the first movement after the criterion time has elapsed (relative to a start-timing cue). Like an impatient passenger pressing a door-close button in the elevator, subjects in these tasks begin responding substantially earlier than the criterion time, and their response frequency increases monotonically as the target time approaches. To define the timing performance of the subject, occasional probe trials are included in which reward is not given at the criterion time. On probe trials, subjects continue to respond beyond the criterion time, but their rate of responding gradually wanes. It is well-known that the peak response-frequency typically occurs at or near the criterion time in these tasks (see Author response image 2A for an example from mice and Author response image 1A for an example from humans). Importantly, given the broad timing distributions, there are still many premature responses in peak procedures, observed in all species, from rodents to birds to primates (Gallistel and Gibbon, 2000).

Although peak procedures generally reveal timing peaks at or near the criterion time, we chose not to use a peak procedure in our study for a crucial reason: timing in peak procedures is explicitly manifested as an accelerating sequence of motor responses; thus, the responses themselves could drive motor-related neuronal activity that could mimic or obscure a neural timing signal, such as a ramping timing signal.

Differential Reinforcement of Low Response Rates (DRL): Historically, the most common alternative to peak procedures for studying operant timing in rodents has been DRL tasks. In typical DRL tasks, rats or mice are rewarded if they wait to respond for at least a criterion time after their last response. If the animal responds prematurely, it is not rewarded, and the response/reward-clock resets (unlike peak procedures).

Self-timed movement tasks: We used a self-timed movement task in our study. Like DRL tasks, reward was given only if the first movement occurred after a criterion time. Unlike DRL tasks however, our selftimed movement was referenced to a start-timing cue rather than the animal’s last response, and thus incorporated an explicit inter-trial period. To keep the animal performing briskly, we also enforced a maximal response window (7 s following the cue) to receive reward. Our lab pioneered self-timed movement tasks in monkeys (Lee and Assad, 2003; Lee et al., 2006), and we believe our mouse study is the first use of a self-timed movement task in rodents.

Animals across species frequently move before the criterion time during timing tasks, even at the expense of reward.

As in the peak procedure, subjects executing DRL or self-timed movement tasks tend to anticipate the criterion time, even though they receive less overall reward. For example, in Lee and Assad (2003), monkeys executing the self-timed movement task had first-movement-time distributions that peaked near the criterion time (2 s), but ~1/3 of trials were premature, and thus unrewarded (Author response image 2B). Rats show a similar anticipatory pattern on DRL tasks (Author response image 2C), although rats tend to move even earlier than monkeys, and on some trials, they are also unable to withhold short-latency reactions to the initial start-timing cue, producing an initial “spike” in the movement-time distributions (Kirshenbaum et al., 2008; Schuster and Zimmerman, 1961).

Mice executing DRL tasks behave very similarly to mice performing our self-timed movement task (Author response image 2D, (Eckard and Kyonka, 2018)). Like rats, mice sometimes react quickly to the cue. They are also “less patient” than the rats: the peak of their timing distribution tends to anticipate the criterion time even more. Our mice showed similar behavior in our self-timed movement task (Author response image 2E). Importantly, in the Eckard and Kyonka study, the same mice were also trained on a peak procedure task with the same criterion interval (18 s), in which the peak frequency of probe-trial responses occurred close to the criterion time (Author response image 2A). This demonstrated that these same mice were capable of accurately estimating the criterion interval and suggested that the difference in peak position between the timing tasks was not the result of poor timing behavior. Rather, it has been emphasized since the 1950s that the “premature” response-peaks found in the DRL tasks belie a more accurate latent timing process, as follows:

Anger (1956) pointed out that if the animal responds early on a trial, it obviously eliminates the opportunity to respond later on that trial (Anger, 1956). The raw frequency of a particular response time is thus “distorted” by how often the animal has the chance to respond at that time. In other words, timing distributions from DRL or self-timed movement tasks – in which only one movement is allowed per trial – should take into account the number of response opportunities the animal had at each timepoint. This is accomplished by computing the hazard function, which is defined as the conditional probability of moving at a time, T, given that the movement has not yet occurred. (The hazard function was referred to as “IRT/Op” analysis in the old DRL literature.) In practice, the hazard function (HF) is computed by dividing the number of first-movements in each bin of the histogram by the total number of first-movements occurring at that bin-time or later – the total “opportunities.” The HF effectively captures the instantaneous probability of moving at a given time. In the peak procedure, that instantaneous probability can be read out directly from the rate of response itself, but in DRL/selftimed movement tasks, the instantaneous probability is a latent variable that must be derived by computing the HF.

To ground discussion of the HF, first consider a “null hypothesis” case: that the animal does not time its response, but rather has a uniform instantaneous probability (over time) of moving after the cue. This equates to a flat hazard function and manifests as an exponential movement-time distribution (modeled in New Manuscript Figure 1C). Indeed, for first training sessions, when the animals were not yet aware of the timing contingency of the task, we found a flat HF on average (following the typical “spike” of short-latency reactions to the cue, New Manuscript Figure 1D).

Next, we computed the hazard functions from our data after the animals had been trained for at least a week in the self-timed movement task. As Reviewer 3 pointed out, the raw first-movement-time distributions in our manuscript showed anticipatory peaks for both the 3.3 s and 5 s criterion times (New Manuscript Figure 1E top). However, HFs computed from those distributions reveal peaks close to the criterion times (New Manuscript Figure 1E bottom). This indicates that the instantaneous probability of moving in our task was maximal near the criterion time, demonstrating that the animals’ behavior was accurately tuned to the target-timing interval. We stress that this HF property is implicit in the shape of the first-movement-time histogram, but is not obvious if one considers that histogram’s peak alone. New Manuscript Figure 1E bottom-right shows average HFs for all 12 GCaMP6f photometry animals, revealing that the peak instantaneous probability of movement was close to the 3.3 s criterion.

In summary, these combined data indicate that after training, the animals “understood” the timing contingencies of the task, in that their instantaneous probability of moving peaked close to the criterion time. In the revised Results section, we have summarized these arguments and also present the hazard functions as evidence that the animals indeed were able to well-estimate the timing contingencies (New Manuscript Figure 1E bottom-right).

Notwithstanding the hazard-function analysis, it might seem surprising that our animals did not adopt a more patient strategy in an effort to receive more rewards. One possibility is that the animals were under-trained. This is unlikely, however, because the animals’ movement-time distributions evolved over the first 4-7 days of training but then were stable over months. Moreover, the animals were indeed capable of being more patient: the mice tested with the 5 s criterion time were first trained for weeks with the 3.3 s criterion, but within only one session of switching to the 5 s task, the mode of the movement-times distribution shifted later. If the mice had adopted that later mode for the 3.3 s task, they would have received rewards at a much higher rate (e.g., New Manuscript Figure 1E top). Clearly, during training, the animals “sought” to maximize the instantaneous movement probability near the criterion time (as revealed by the hazard function), rather than to optimize average reward rate. We can only speculate as to the cognitive pressures driving this strategy, but this behavioral pattern may reflect particularly strong temporal discounting of reward value, driving the animals to acquire rewards as quickly as possible when they become available.

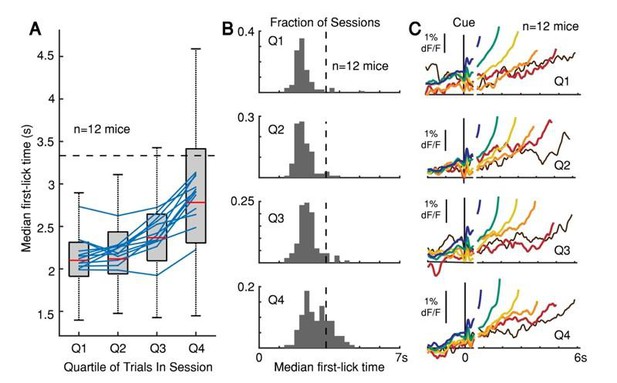

Although previous rodent DRL studies invariably found frequent movements before the criterion time, there are two additional reasons why our mice might have been even “jumpier”:

First, we imposed a maximum movement-time window (unlike DRL studies), which may have added additional temporal urgency that drove earlier responses. We have anecdotal evidence from early training without the maximum movement-time window that is consistent with that possibility.

Second, our animals were water deprived, and their thirst-urgency may have driven them to move at earlier times, even at the expense of fewer rewards. Our mice presumably sated over the course of a session; for example, as sessions progressed, animals also licked less frequently during the inter-trial interval and made shorter lick bouts in response to reward. We also noticed that (unsurprisingly) animals tended to move progressively later over the course of a daily session, presumably as their thirst-urgency eased with accumulated rewards (Author response image 3A-B). We were initially concerned that this non-stationarity could artifactually produce differences in dopaminergic signals on early- vs. late movement trials, based on the different proportion of trial outcomes over the course of a session. In our original manuscript, we addressed this concern by dividing sessions into quartiles and comparing the dopaminergic signals (as a function of first-movement-time) within and across each quartile. (We discussed this analysis in our “dF/F Validation Methods” section of the original and revised manuscripts.) We detected no differences in the relative pattern of ramping or baseline offset over the course of sessions (Author response image 3C). For example, the relative difference in average ramping slope for trials with a first-lick-time at 2 s vs. 4 s was similar regardless of whether those trials occurred at the beginning or end of the session.

This inter-quartile comparison also helps to address Reviewer 3’s concerns about interpretability. First, the basic pattern of dopaminergic signals was similar whether the animals had fewer “correct” trials (beginning of the session) or more correct trials (toward the end of the session). Second, because many variables are presumably changing over the course of a session (e.g., thirst, motivation, vigor/fatigue, etc.), the consistency in the dopaminergic signal across the session suggests these signals are related instead to what is the same across the session – that the animal has to time its movement relative to the cue on a given trial.

In their summary, the editors stated, “Issues with the behavioral performance and task design make it difficult to infer how signals correspond to internal processes such as reward anticipation, RPE, behavioral inhibition, or—as the manuscript suggests—timing.” As we have shown here, the behavior we observed is consistent and interpretable in the context of behavioral timing. However, we reiterate this really wasn’t the point we were trying to make! Given the vigorous debate in the literature about “what dopamine signals represent,” it is likely that many different motivating factors (anticipation, RPE, value, etc.) are multiplexed into creating the dopaminergic signals that we observed during selftimed movements. (We have posted a BiorXiv manuscript showing how RPE signals could explain premovement ramping in our task, based on a theory developed by our colleague Sam Gershman; see (Hamilos and Assad, 2020).) But we are not asking about the (undoubtedly complex) origin of the dopaminergic signals, but rather how dopaminergic signals influence behavior in real-time.

Specifically, we desired to relate trial-by-trial differences in dopaminergic signaling to the timing of the animal’s movement, and to relate causal manipulations of dopaminergic activity to movement timing. As Reviewer 1 noted, we have “link[ed] DA activity to the timing of a reward-related decision extremely well.” That was exactly our goal.

The peak of the timing distribution becomes later over the course of a behavioral session, but the pattern of dopaminergic responses as a function of movement time does not change.

(A) Median first-lick time divided into quartiles across sessions (only first-licks between 0.7-7 s considered to exclude rapid reactions and licks occurring after end-of-trial). Boxplot shown for individual photometry sessions with at least 100 first-licks (102 sessions total, red line: median, box: 25-75th percentiles, whiskers: 1.5 IQR). Blue lines: individual animal averages across sessions; n=12 mice. (B) Histograms of median first-lick time for each of the 102 sessions shown in A. (C) Corresponding SNc GCaMP6f signals from DAN cell bodies averaged separately for each quartile, aligned both on cue onset (left) and first-lick-time (right). Traces plotted to 150 ms before first-lick to exclude movement-related response. Trials pooled into bins of 1 s each, e.g., blue: 1-2 s, green: 2-3 s… etc.

Editor point 2. It will be key to nail down the legitimacy of the claim that dopamine ramps and amplitudes at movement onsets on single trials. The main concerns (points 1-4) of R2 and point 5 of R3 well-articulate this concern.

This point was extremely useful, because it led us to consider in much greater depth questions of (i) single-trial dopaminergic dynamics, and (ii) how this signal may be influencing movement timing. We have added several major new analyses to the revised manuscript to address these points, culminating in a critical new analysis that revealed a more nuanced, probabilistic interpretation of the role of dopaminergic signals in movement timing.

(i) Are single-trial dopaminergic dynamics slow ramps, or are they better explained by discrete steps? In the original manuscript, our single-trial analyses consisted of a movement-time decoding model that incorporated GCaMP6f-signal threshold-crossing time as a predictor. This model was based on well-established diffusion-to-threshold models that have been extensively used by Shadlen and colleagues (and many others) to characterize ramping neural signals in the context of perceptual decision-making tasks (e.g., (Roitman and Shadlen, 2002)). Nevertheless, Reviewer 3 (R3) correctly pointed out that slow ramping signals on average could be due to slow ramping on single trials, or could be due to discrete steps on single trials that are distributed throughout the timed interval from trial-to-trial. Either underlying single-trial dynamic could result in slow ramping when averaged across trials.

R3 is probably aware that this question of “ramping vs. stepping” has been vigorously debated in the perceptual decision-making field. Alex Huk and Jonathan Pillow first suggested that average ramping dynamics (in single-unit recordings from monkey parietal cortex) could instead be explained by discrete step-functions occurring at different times from trial-to-trial (Latimer et al., 2015). Shadlen et al. (2016) immediately challenged this interpretation on analytical grounds – and the debate has continued to simmer (Latimer et al., 2016; Shadlen et al., 2016; Zoltowski et al., 2019; Zylberberg and Shadlen, 2016). However, Sahani and colleagues have argued that the step vs. ramp question may be fundamentally non-resolvable (Chandrasekaran et al., 2018). They showed that classification models are extremely sensitive to model parameterization, to the extent that different data-supported model parameterizations can produce opposite classification results when applied to the same simulated, ground-truth datasets. This confusion may be due to contamination of signals by ongoing neural activity unrelated to the decision process, as well as detection noise (Chandrasekaran et al., 2018).

Nonetheless, prompted by R3, we decided to take a stab at the “step vs. ramp” question in our data set. At the outset, we note that for single-trial steps to produce average ramping dynamics, the steptimes must be randomly distributed across the timed interval from trial-to-trial. A consistent, perimovement step (as R3 seemed to suggest) would not produce slow ramping on average, but rather a sharp jump at the time of movement – and that was not what we observed. However, we agree that a simple threshold-crossing analysis might not be able to distinguish a single-trial ramp vs. step process, because relatively late threshold-crossing times are only possible on trials with relatively late movements (e.g., a 3 s step-time cannot occur on a 2 s trial, by definition). To wit, our original singletrial threshold-crossing analysis made no assumptions about the underlying trial dynamics (step vs. ramp). However, we see R3’s point that the title “slowly-evolving dopaminergic activity determines the timing of self-timed movement” would not necessarily be uniquely supported by a simple thresholdcrossing analysis.

Caveats aside, with advice from Josh Tenenbaum at MIT, we implemented a single-trial hierarchical Bayesian model to analyze our single-trial GCaMP6f signals, using probabilistic programs in the novel probabilistic programming language, Gen.jl (Cusumano-Towner et al., 2019). These analyses are summarized in New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 2. These programs infer underlying signal dynamics and return a probabilistic classification of single trials as either linear ramps or discrete steps. Both the step and ramp models were individually optimized to fit single-trial data, and both models were capable of capturing intuitive step and ramp fits for ambiguous signals that, by eye, could have “gone either way.” However, like previous efforts, our model returned inconclusive results, with about half of trials being better classified by a ramp and half by a step function. Given the findings of Chandrasekaran et al. (2018), this ambiguity was perhaps not surprising.

We thus took a step back and examined three additional, complementary approaches to tease the two models apart:

Multiple threshold levels. Although a simple threshold-crossing analysis does not definitively distinguish between underlying step vs. ramp dynamics, the two types of dynamics will have a distinct relationship with respect to different threshold levels, as our lab previously showed (Maimon and Assad, 2006). Consider the idealized simple ramp and step dynamics shown in New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 3A. If we draw three arbitrary thresholds across each dataset, the thresholdcrossing time will always be the same for the discrete step model, regardless of threshold level (New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 3B, blue lines). But the ramp model will have a thresholdcrossing time progressively closer to the first-lick time as the threshold is increased (New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 3B, red lines). That is, for single-trial ramping, the slope of the thresholdcrossing vs. movement time relationship will increase as the threshold is increased (New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 3B). In the original manuscript, we showed that the slope of the relationship between threshold-crossing time and first-lick time increased with increasing threshold level for a single behavioral session, consistent with the ramp model, but inconsistent with the step model. In the revised manuscript, we performed the same multiple-threshold analysis for all SNc GCaMP6f sessions in our 12 mice. Across animals and sessions, we found the slope of the relationship increased markedly from low to high as threshold level is increased, supporting the slow-ramp model on single trials (New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 3C).

Aligning trials on step. If single trials involve a step change occurring at different times from trial-totrial, then aligning trials on that step should produce a clear step on average, rather than a ramp (Latimer et al., 2015). We thus used the Bayesian step model to find the optimal step position for each trial, and then aligned single-trial signals to that optimal step position. However, GCaMP6f signals aligned to the fitted step position and averaged did not yield a step function, but rather detected an apparent transient superimposed on a “background” ramping signal (New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 4A). Step-aligned tdTomato and EMG averages showed a small inflection starting at the time of the step, but neither signal showed a background of ramping, unlike the GCaMP6f signal. This suggests that the detected “steps” were likely transient movement artifacts superimposed on the slower ramping dynamic, rather than bona fide steps.

Variance analysis. The ideal step model holds that steps occur at different times from trial-to-trial, producing a ramping signal when averaged together. In this view, the trial-by-trial variance of the signal across trials should be maximal at the time at which 50% of the steps have occurred among all trials, and minimal at the beginning and end of the interval (when no steps and all steps have occurred, respectively). To examine this, we derived the optimal step time for each trial using the Bayesian step model, and then calculated variance as a function of time within pools of trials with similar movement times (pooled at 1 s intervals). Rather than exhibiting an inverted “U” shape with respect to cumulative probability of when the steps occurred, the signal variance showed a monotonic downward trend during the timed interval, with minimal variance at the time of the movement, rather than at the point at which 50% of steps had occurred among trials (New Manuscript Figure 6—figure supplement 4B). This is inconsistent with a step model but consistent with a ramp-to-bound model, in which signals trend toward a similar level just before movement onset (Roitman and Shadlen, 2002).

Overall, we did not find evidence for a step dynamic on single trials; on the contrary, our combined observations concord with slow ramping dynamics on single trials. This indeed suggests that “slow dopaminergic dynamics” are informative of movement time. However, we again stress that our decoding models (New Manuscript Figure 6 and New Manuscript Figure 8) make no assumptions about the underlying single-trial dynamics.

(ii) Do dopaminergic signals encode the moment-to-moment probability of movement initiation? Reviewer 2 (R2) was concerned that our original movement time decoding model used only one point in the signal – a threshold crossing. We chose the threshold-crossing model based on common drift-diffusion-to-threshold models used to effectively describe the timing of perceptual decisions (see section (i) above).

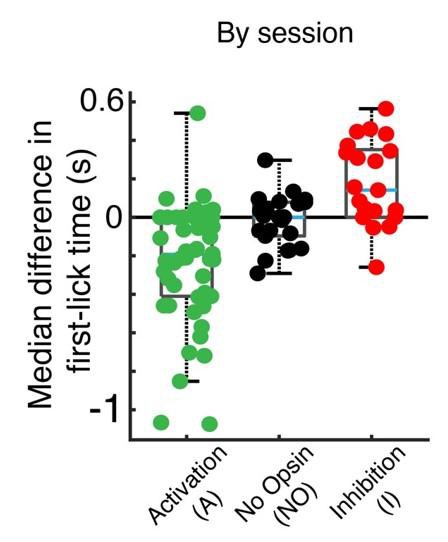

However, R2’s comment really got us thinking. As described above, our evidence suggests that a slowly-changing dynamic characterizes single-trial dopaminergic signals—but what is the actual link to movement initiation? Our optogenetic stimulation and inhibition results suggested that dopaminergic signaling influences the moment-to-moment probability of movement onset: stimulation/inhibition shifted the probability distributions of movement times to earlier/later times, rather than immediately triggering or inhibiting movement (New Manuscript Figure 7B). Thus, in addition to trying to predict the exact movement time from single trial dynamics (which we already knew we could do to some extent from the threshold-crossing GLM), we asked whether we could predict the moment-to-moment probability of movement from the dopaminergic signals. In this view, we would take into account the full time-course of the dopaminergic signals, not just the single threshold crossing, which also addresses R2’s original suggestion.

As described in our response to Editor point #1, we showed that the hazard function – the probability of movement initiation given that movement has not yet occurred -- reveals the animals’ (accurate) latent timing process. The hazard function, by definition, defines the instantaneous probability of movement initiation; thus, if dopaminergic signals are predictive of the moment-to-moment probability of movement initiation, we should be able to reproduce the behavioral hazard function from the dopaminergic signals.

To test this hypothesis, we derived a nested probabilistic movement-state decoding model (New Manuscript Figure 8A). We applied a GLM based on logistic regression, in which each moment of time is classified as either a non-movement (0) or movement (1) state (New Manuscript Figure 8A-B). The model allows us to examine whether various measured parameters are good predictors for the probability of transitioning from the non-movement state to the movement state. In our initial model selection, we found that the instantaneous dopaminergic signal itself was a robustly significant predictor of movement state, whereas previous trial outcomes were insignificant contributors to the model (New Manuscript Figure 8—figure supplement 1).

The continuous dopaminergic signal was indeed predictive of current movement state at any time t – and up to 2 seconds in the past (New Manuscript Figure 8C). However, remarkably, the signals became progressively more predictive of the current movement state at t as time approached t. That is, the dopaminergic signal levels closer to time t tended to absorb the behavioral variance explained by more distant, previous signal levels (New Manuscript Figure 8C). (Note also that this observation is consistent with a diffusion-like ramping process on single trials – in which the most recent measurement gives the best estimate of whether there will be a transition to the movement state – but this finding is difficult to relate to a step process on single trials.)

We applied the fitted probabilities of being in the movement state to derive the fitted hazard function for each behavioral session. The dopaminergic signals were remarkably predictive of the hazard function, both for individual sessions and on average, explaining 65% of the variance on average (New Manuscript Figure 8D). Conversely, when the model was fit on the same data in which the timepoint identifiers were shuffled, this predictive power was essentially abolished, with only 5% variance explained on average (New Manuscript Figure 8E). These results of these analyses are included in (entirely new) New Manuscript Figure 8 in the revised manuscript.

Together, these results demonstrate that slowly-evolving dopaminergic signals are predictive of the moment-to-moment probability of movement initiation. When combined with the optogenetics results, they demonstrate that dopaminergic signals causally set this moment-to-moment probability of movement. To our knowledge, this is a completely novel view of how dopaminergic signals can influence movement initiation. Moreover, because this analysis takes into account the entire timecourse of dopaminergic signals, the probabilistic decoding model also addresses R2’s suggestion. (Thanks R2 – that was an incredibly useful suggestion!)

Editor point 3. We also encourage you to address the statement that ramps existed before licks outside the task, which shows the irrelevance of the task for the finding. Showing examples of this phenomenon might help. And we encourage you to consider how this finding relates to the central claim of 'timing.'

We set out to determine how dopaminergic signaling influences the timing of “self-initiated” movements, movements that, by definition, depend on some internal cognitive process to determine when they are initiated (rather than occurring in response to abrupt external sensory input; (Lee and Assad, 2003; Lee et al., 2006)). However, to detect whether that internal process unfolds relatively quickly or slowly, we required some reference event to align both behavior and neural signals. Our self-timed movement task does exactly that: it provides a visual/auditory cue-event that presumably “starts the clock”. Having an unambiguous time-reference point was the key element that allowed us to relate variations in dopaminergic signaling to variations in the timing of movement initiation.

Indeed, we found striking evidence that dopaminergic signals were informative of the timing process, both on average and from trial-to-trial (New Manuscript Figures 1,6, and 8). However, it is not clear that the specific processes we observed in the context of the self-timed movement task can be generalized to all “self-initiated” movements. Animals obviously also make “spontaneous” movements outside the context of contrived behavioral tasks in a lab. For example, our animals made exploratory licks between trials, when there was no explicit timing requirement governing these movements. We asked whether similar ramping might be present before these spontaneous licks precisely because we were curious whether the slow dopaminergic dynamics may be generalizable to all spontaneous movements –or rather are specific to our behavioral task, with its explicit timing requirement.

For the spontaneous licks, one approach could have been to just globally average the dopaminergic activity preceding every spontaneous lick during the inter-trial period, as done in previous studies that allowed animals to initiate movements ad libitum (da Silva et al., 2018; Howe and Dombeck, 2016). But at best, this global averaging could only provide evidence that activity ramps up before spontaneous licks. Obviously, global averaging throws away potential variation in dopaminergic dynamics that might be related to variation in movement time (and remember, such variation was the crux of our self-timed movement task!). So instead of globally averaging signals before spontaneous licks, we decided to pool spontaneous lick events with respect to the only possible reference we had – the time elapsed since the previous spontaneous lick (example shown in New Manuscript Figure 8—figure supplement 2). We didn’t expect this to be a great reference point, but it was the only reference available. Although the patterns were noisy and quite variable between animals, we did find variation in ramping in some animals that was indeed related to the elapsed time since the previous lick. To be clear, it is not surprising that these patterns were less stereotyped and well-formed—there is no strong reason a priori to believe that the previous lick would serve as a “good” reference event for the next spontaneous lick. What was surprising was that we found any differences in the ramping slope at all. Previous studies have reported short-latency increases in dopaminergic signaling within 500 ms of spontaneous movement initiation (Coddington and Dudman, 2018; da Silva et al., 2018; Dodson et al., 2016; Howe and Dombeck, 2016; Wang and Tsien, 2011), but never tried to relate that activity to the elapsed time since the last spontaneous movement.

Our findings for spontaneous licks suggest that slow dopaminergic dynamics may occur before any self-initiated movement, whether or not there is an explicit timing requirement. (An important caveat is that it is possible that our highly trained animals may have been “practicing” their timed movements between trials.) Thus, we are not concluding that the signals we observed are specific to explicit timing tasks – but nor was that the goal of our paper! But it is critical to emphasize that our findings for the spontaneous licks are far less conclusive than for our self-timed movement task. The presence of an unambiguous timing reference in the self-timed movement task (the visual/auditory start-timing cue) was the critical design feature that allowed us to detect the fine-grained relationship between the dynamics of dopaminergic signal and the dynamics of movement. We have made this point more clearly in the revised manuscript.

Editor point 4. We encourage you to clarify that the task was not designed to specifically rule in or out the many models of what dopamine encodes and rather clarify that the goal of the study is to identify dopamine relationship to upcoming movements or behavioral transitions. Fully addressing R3 comment 1 is necessary.

We believe we have fully addressed R3 Comment 1 in Editor points #1 and #3. We will simply add here that the key finding of our study is that dopaminergic signals predict movement timing remarkably well and are also causal to behavioral output—both of which are novel findings. Put differently, our study is concerned with the downstream (behavioral) impact of dopaminergic signals, and we remain agnostic to the origin(s) of the dopaminergic signal itself. Whether dopaminergic signals encode value, ongoing RPE, vigor or otherwise, our results demonstrate that these signals can causally influence behavior, potentially by modulating the instantaneous probability of initiating a movement. Moreover, the specific temporal variation of the dopaminergic signals was the key observation: regardless of their origin, the signals were excellent predictors of the (highly variable) timing of movement. To our knowledge, this is an entirely novel view, although it accords with the longstanding view (mainly from the clinical perspective – Parkinson’s disease, etc.) that dopamine somehow influences movement initiation.

[Editors’ note: what follows is the authors’ response to the second round of review.]

Reviewer #1:

Hamilos et al. image DA axonal and neuronal CA signals in mice engaged in a self-timed lick task. They observed a ramping signal prior to lick onset that could predict, on average when a mouse would lick. While ramps in DA Ca signals have been observed as animals locomote towards known rewards (e.g. Howe et al., Hamid et al., Mohebi et al., all cited) and while DA activity is known to exhibit correlations with movement onsets – what's new and potentially important in this paper is how well the DA ramps could predict movement onset time – even on single trials. Complementing this finding were causal experiments where photoactivation or inhibition on single trials could promote or delay movement initiation. Given the amount of effort invested into the relationship between DA activity and upcoming movements – it is surprising that the strong correlation between the DA ramp and movement initiation (or decision, see discussion of Guru et al., paper below) hasn't been so clearly observed before (to my knowledge). This paper links DA activity to the timing of a reward-related decision extremely well.

Figure 3 of Guru et al. (unpublished biorxiv paper from Warden lab, not cited) shows a similar result as this paper except the internally timed action is not to produce movement but rather to terminate movement (stop running on a wheel). The fact that the same ramp is observed in both of these conditions undermines the connection that the authors make about ramping DA and decision to move. Taken together, it seems the DA ramps are more about the timing of a self-paced decision (whether it be to start or to stop doing something) than about movement initiation. The authors may want to re-tweak the interpretations of this paper to allow for this more general perspective.

This is a great catch! Guru et al.’s work was pre-printed about a week after our own, and we took the opportunity to read it carefully. We were very comfortable re-tweaking our interpretation to allow for this more general perspective. We note an exciting connection to our initial motivation by movement disorders like Parkinson’s—patients not only have difficulty initiating movement, but also with changing movement (e.g., perseveration), implying a more general need for dopamine to flexibly transition between behavioral and possibly cognitive states. We’ve always liked this idea, but with our movement task alone, we were not in a position to make that argument. In the revised Discussion, we now suggest that our results may apply more generally to behavioral transitions, which would encompass both movement initiation and changing to a different movement, like stopping. We note that we are not entirely convinced that stopping isn’t in of itself a kind of movement initiation— counterbalancing musculature must be invoked to stop the momentum of the body and the running wheel that is different from the ongoing movement of running. But “behavioral transition” seems a good way to describe both the self-initiated lick and the stopping behavior.

Reviewer #2:

In this study Hamilos and colleagues measured dopamine signals in mice performing a self-timing task. They took advantage of the variability in the first lick time to study how dopamine signaling preceding the first lick varied with the timing of the first lick. While a number of studies have reported short-latency (<500 ms) increases in dopamine activity immediately preceding movements, the authors make a number of novel findings. First, dopamine photometry signals ramped up over several seconds preceding the first lick. Second, the steepness of this ramping, even the amount of baseline signal predicted the first lick time. Third, optogenetic activation and inhibition reduced or increased the first lick time. The authors are commended for performing several different types of photometry experiments. The authors conclude that dopaminergic signals unfolding over seconds control the timing of movements, but not as much the ability to move itself. While the work is novel and adds an interesting perspective on the function of dopaminergic neurons, there were concerns about some of the evidence for the first two claims, as well as insufficient detail in some of the statistical analysis that make it difficult to fully judge the paper's merits. The main concerns are detailed below.

1. Lines 151-153: "we observed systematic differences in the steepness of ramping that were highly predictive of movement timing (Figure 1D-E)." The reviewer agrees this is quite evident from the ramping curves, but still the authors should formally show the fact that the steepness (i.e., slope) of ramping is predictive of timing. The decoding model in Figure 6 goes some way toward this goal, but it seems Figure 6 uses time to threshold rather than the slope. It would be worthwhile to check in Figure 1 or Figure 2 whether the time to first lick is negatively correlated with slope of ramping.

We did not quantify the average slopes in New Manuscript Figure 2 for two reasons: First, Stimulated by R2’s feedback, we derived a new logistic regression analysis to characterize single-trial dynamics that takes into account the entire time-course of dopaminergic signaling on single trials (See Editor point #2), not just a single threshold crossing (New Manuscript Figure 8). This model suggests a more nuanced view of dopaminergic dynamics in which dopaminergic signaling sets a moment-to-moment probability of unleashing a prepotent movement. We also quantitatively analyzed the dynamics on single trials, but we could not definitively characterize those dynamics as linear ramps vs. discrete steps, as others have found (see Editor point #2). Because we did not find definitive evidence for sloping on single trials, we focused on movement-time decoding models that make no assumptions about the specific shape of single-trial dynamics (New Manuscript Figures 6 and 8). In this light, we felt that quantifying the slope of the average ramping responses would distract from the larger point.

We think these new analyses and interpretations will satisfy R2. However, if R2 feels strongly that we should quantify the average slopes in New Manuscript Figure 2, we can do so; it’s easy enough! But we would have to immediately add a caveat about the complexity of the underlying single-trial dynamics. In the revised manuscript, we have added a line at the end of the section describing the qualitative shapes of the average signals to let readers know we will be quantitatively addressing single-trial dynamics in a subsequent section of the paper.

2. Figure 4: similar to the previous comment. The reviewer found it difficult to interpret Figure 4 and suggests including a more traditional analysis, such as a Pearson correlation between the time to first lick and the level of pre-cue baseline dopamine.

We have eliminated this figure and focused on simpler analyses in the text, as per your suggestions. We also added the Pearson correlation coefficient for the relationship between baseline-signal amplitude and movement times in the Results text when referencing New Manuscript Figure 2 (r = -0.89).

3. Figure 6: the reviewer was confused about the contribution of the pre-cue baseline signal (predictor # 7) to the nested model. From the results in Figure 6B and 6C it appears that the pre-cue signal has almost zero contribution to the model (it was the only predictor with a non-significant weight in 6B). But this seems to contradict the authors' claim that "higher pre-cue, baseline DAN signals are correlated with earlier self-timed movements." If baseline signals do indeed correlate with timing of movements, shouldn't the weight of predictor # 7 be higher? This reviewer may have misunderstood some important detail, so some clarification of this issue in the text would be helpful. The reviewer also requests clarification of the difference between the "offset" (Predictor # 0) and "pre-cue" (Predictor # 7) as they both seem to be referring to some sort of baseline signal.