Genetic determinants facilitating the evolution of resistance to carbapenem antibiotics

Figures

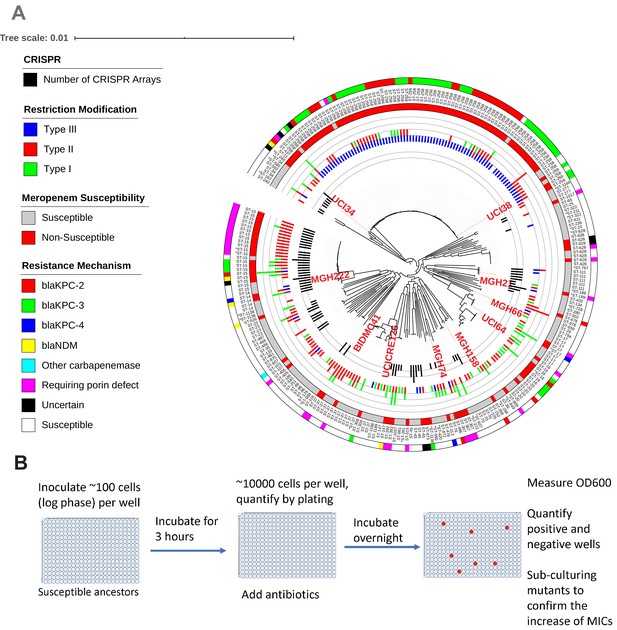

Ten phylogenetically diverse carbapenem-susceptible K. pneumoniae isolates were selected from a collection of 267 K. pneumoniae clinical isolates.

(A) The selected isolates are highlighted in red. In this phylogenetic tree, from inner to outer circles, the content of the CRISPR-Cas systems, restriction–modification systems, susceptibility to carbapenems, and sequence types are indicated. For carbapenem-resistant isolates, the resistance mechanism is also indicated. (B) Scheme of the modified Luria–Delbrück system. Exponential-phase growing cells are diluted and inoculated into 384-well plates, followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 hr. Antibiotics were then added at the concentrations of 1.1× MICs or at specified concentrations, and cultures were incubated at 37°C overnight. OD600 was measured the next day, and positive and negative wells were quantified. Mutants from each plate were sub-cultured in MHB medium supplemented with the same antibiotics at the same concentrations used for the selection, and saved in 25% glycerol stocks for future analysis. Mutants that did not grow up in the sub-culturing were excluded from the calculation of mutation frequencies.

The evolution of carbapenem resistance is affected by genetic background of the isolates.

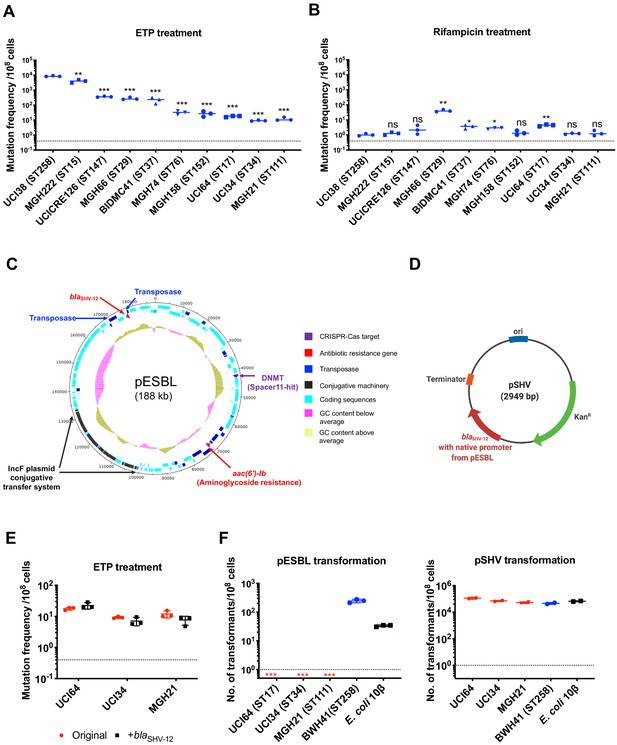

(A) Mutation frequencies of 10 clinical isolates under treatment with ertapenem. Five isolates, UCI38 (ST258), MGH222 (ST15), UCICRE126 (ST147), MGH66 (ST29), and BIDMC41 (ST37), have relatively greater mutation frequencies to ertapenem (>100 mutants per 108 cells) than the other five isolates. Comparing to UCI38 (ST258) that has the highest mutation frequencies to ertapenem, all isolates have significantly different mutation frequencies. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis between UCI38 (ST258) and other isolates. (B) Mutation frequencies of 10 clinical isolates under treatment with rifampicin. Isolates with relatively high-level mutation frequencies to ertapenem do not necessarily have high-level mutation frequencies to rifampicin. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis between UCI38 (ST258) and other isolates. (C) Diagram of pESBL, an ESBL-encoding plasmid isolated from UCI38 (ST258). (D) Diagram of pSHV, a multi-copy laboratory plasmid containing the native promoter and coding region of the ESBL gene blaSHV-12 amplified from pESBL. (E) The ESBL gene, blaSHV-12, was amplified from pESBL and expressed in three isolates lacking an ESBL gene and with relatively low-level mutation frequencies to ertapenem. However, mutation frequencies to ertapenem were not changed compared to the original strains lacking an ESBL gene (red). Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis to compare the original strain with the corresponding strain overexpressing blaSHV-12, with p>0.05 for all three pairs. (F) Transformation efficiencies of pESBL (left) or pSHV (right) in three isolates lacking ESBL genes (red) and with relatively low-level mutation frequencies to ertapenem. As controls, these two plasmids were also transformed into another ST258 strain BWH41 (blue), which does not carry ESBL genes, and a strain of E. coli 10β (black). pESBL could not be transformed into these three isolates but it could be transformed into BWH41 (ST258) and E. coli. In contrast, the laboratory construct pSHV was successfully transformed into all strains tested. For all experiments in (A, B, E, F) two to three independent biological replicates were performed. Data from independent experiments were plotted individually with error bars plotted as the standard deviation. The limit of detection is indicated with a dashed line, and the asterisk (*) under the dashed line indicates frequencies under the limit of detection. *p<0.05; **p<0.005; ***p<0.0005; ns, not significant.

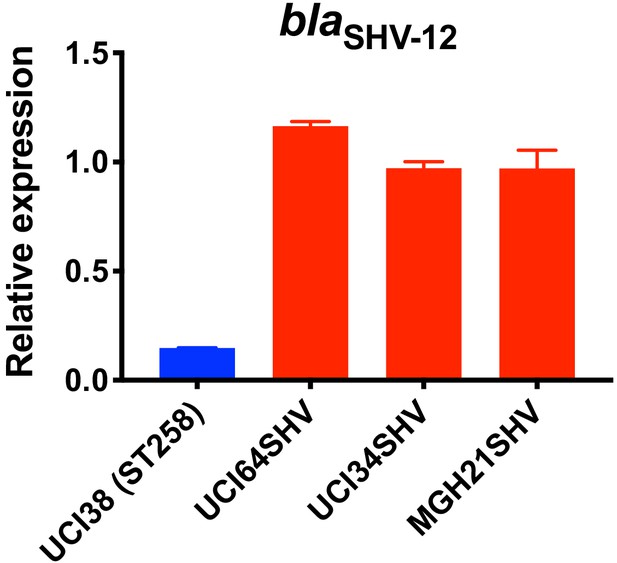

Relative expression of blaSHV-12 in three strains overexpressing blaSHV-12 through pSHV.

BlaSHV-12, including the promoter region, was amplified from UCI38 and expressed in three strains lacking an ESBL gene. The express levels of blaSHV-12 in these overexpression strains were higher than it in UCI38 because pSHV is a multi-copy plasmid. RT-qPCR data was normalized to 16S rRNA. Experiments were repeated three times, and error bars were plotted as standard deviation.

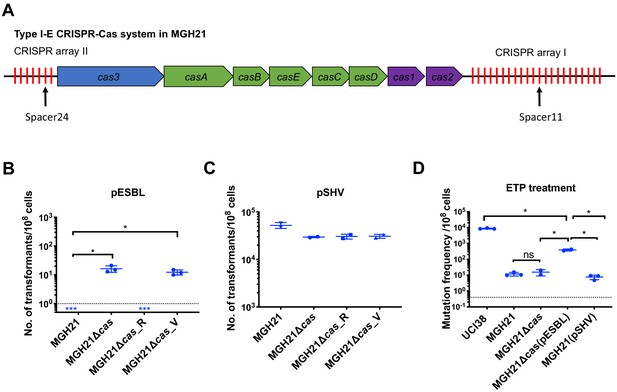

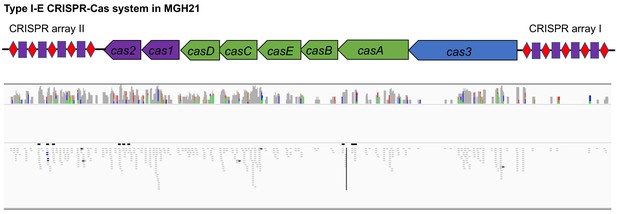

Type I-E CRISPR-Cas system in MGH21 (ST111) prevents the acquisition of pESBL but the presence of pESBL alone does not account for high mutation frequencies.

(A) Type I-E CRISPR-Cas system in MGH21 (ST111). The two CRISPR arrays and the position of two spacers (Spacer11 and Spacer24) that align to plasmids encoding resistance genes are indicated. Spacer11 aligns to the DNMT gene located on pESBL _(Figure 2C). (B, C) Transformation efficiencies of pESBL (B) or the lab construct pSHV (C) in MGH21, MGH21∆cas, MGH21∆cas_R with CRISPR-Cas complementation, and MGH21∆cas_V with control vector complementation. pESBL could only be transformed into MGH21 strains in which the CRISPR-Cas system was deleted (MGH21∆cas and MGH21∆cas_V), whereas pSHV could be transformed into all strains at similar efficiencies. (D) Mutation frequencies of UCI38 (ST258), MGH21, MGH21∆cas, MGH21∆cas(pESBL), and MGH21(pSHV) with ertapenem treatment. The deletion of the CRISPR-Cas system (MGH21∆cas) and the introduction of pSHV (MGH21(pSHV)) did not affect the mutation frequencies. In contrast, the introduction of pESBL (MGH21∆cas(pESBL)) increased mutation frequencies, indicating that some factors on pESBL other than the ESBL gene affect the mutation frequencies. However, mutation frequencies of MGH21∆cas(pESBL) were still significantly lower than these of UCI38, indicating that more factors in the genetic background of UCI38 contribute to the high-level mutation frequencies. All experiments were performed in triplicate and data were plotted individually. Error bars were plotted as standard deviation. The limit of detection of each assay is indicated with a dashed line, and the asterisk (*) under the dashed line indicates that the transformation efficiencies are below the limit of detection. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for all statistical analysis; an asterisk marking a pair-wise comparison denotes a p<0.05.

RNA-seq data shows that cas genes and most spacers are expressed in MGH21.

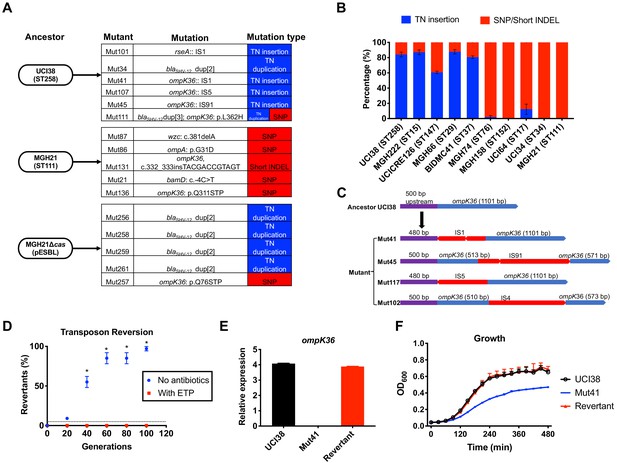

Transposon insertional mutagenesis causes frequent and reversible inactivation of porin genes in isolates with high-level mutation frequencies to ertapenem.

(A) Mutation types (transposon insertion/duplication [blue] vs. SNP [red]) identified via WGS in ertapenem resistant mutants of UCI38 (ST258), MGH21 (ST111), and MGH21∆cas(pESBL). The majority of mutants that carry pESBL (UCI38 and MGH21∆cas(pESBL)) have transposon-mediated mutations, while only SNPs or short insertion/deletions were observed in mutants of MGH21. (B) Relative quantification of the propensity of 10 selected isolates to undergo transposon insertion (blue) versus SNP acquisition (red) in ompK36 during ertapenem treatment. For each of these strains, 50–100 mutants were isolated, and the types of mutation in ompK36 locus, if any, was determined via Sanger sequencing. Transposon insertions occurred at ~10 times higher frequencies than the acquisition of SNPs or short insertion/deletion in strains with higher level of mutation frequencies to ertapenem. (C) Illustration of ompK36 inactivation by four transposons in UCI38. Four representative mutants derived from UCI38 were selected and the insertion sites were determined by Sanger sequencing. (D) Transposon disruption of ompK36 was reversible. A representative ertapenem resistant mutant with an IS1 insertion in ompK36, Mut41, was cultured in the presence or absence of ertapenem. Every 20 generations, colony PCR targeting ompK36 locus was performed on the culture to quantify the percentage of the population that had lost the transposon insertion at this locus. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis at each time point to compare the cultures with and without antibiotics. (E, F) The relative expression of ompK36 (E) and growth curves (F) of UCI38 (black), Mut41 (red), and one representative revertant of Mut41 (blue). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars are plotted as the standard deviation.

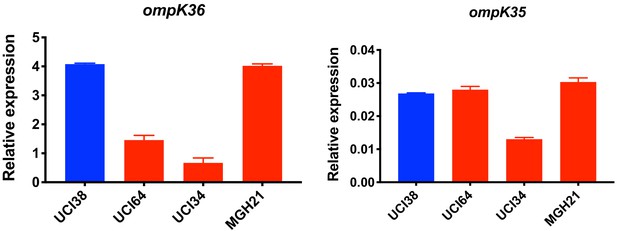

Relative expression of ompK36 and ompK35.

RT-qPCR data was normalized to 16S rRNA. Experiments were repeated three times and error bars were plotted as standard deviation.

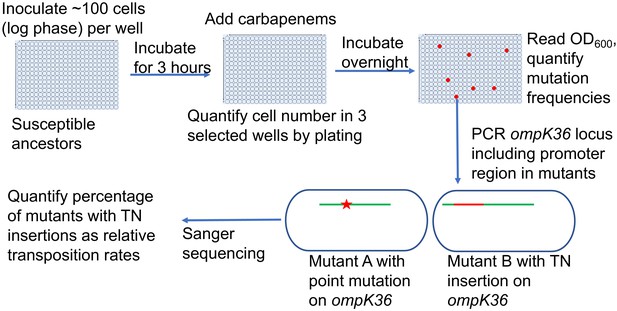

Scheme of the assay for quantification of transposon insertions and SNPs in ompK36.

Following the isolation of resistant mutants from the modified Luria–Delbrück system, PCR targeting ompK36 locus, including the upstream 500 bp region, was performed and the PCR products were Sanger sequenced to determine whether there were mutations in the targeted region and the types of mutations. Numbers of mutants carrying transposon insertions or SNPs in ompK36 locus and promoter regions were recorded, and the percentages of mutants with TN insertions or SNP/short INDEL were calculated.

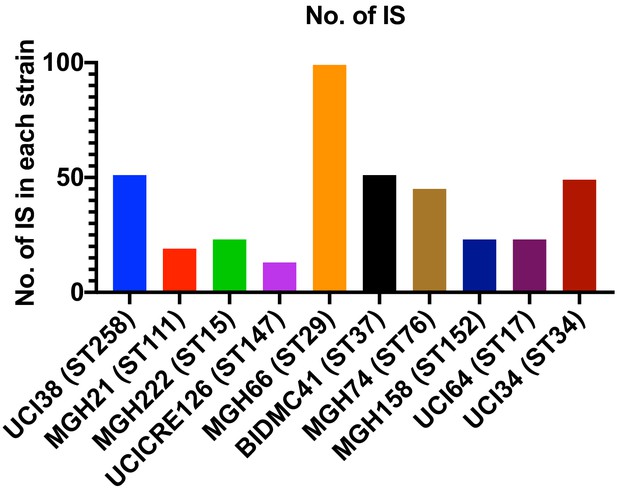

Copy number of ISs in each strain.

There is no correlation between the copy number of ISs and the relative level of transposon insertion in ompK36 locus.

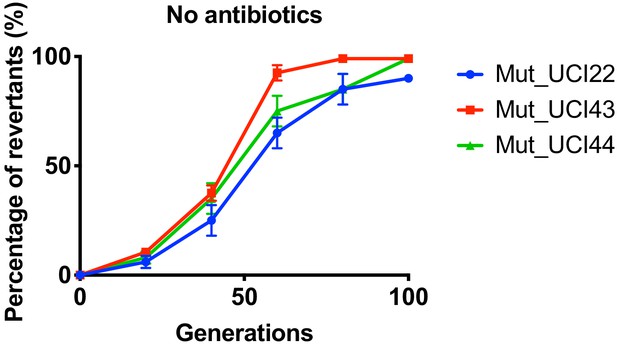

Reversion of TN-insertion mutants derived from UCI22, MGH66 and BIDMC41.

In the absence of antibiotics, mutants carrying transposon insertion in the ompK36 locus and derived from UCI22, MGH66, and BIDMC41 could loss the transposon insertion over ~100 generations. Experiments were repeated three times, and error bars were plotted as standard deviation.

Ertapenem and faropenem treatment are not only associated with higher mutation frequencies, but they also promote the evolution of meropenem resistance.

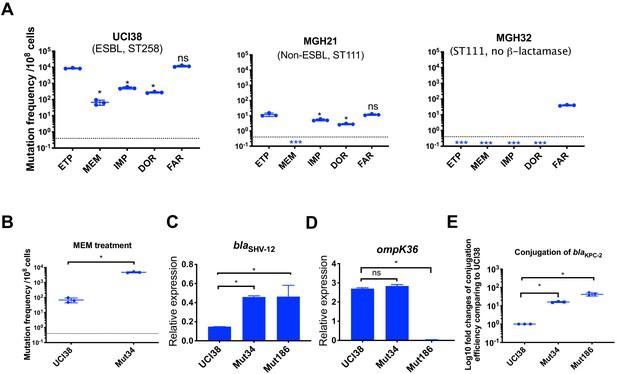

(A) Mutation frequencies of three representative isolates, UCI38 (ST258), MGH21 (ST111), and MGH32 (ST111, no β-lactamase), under separate treatment with ertapenem (ETP), meropenem (MEM), imipenem (IMP), doripenem (DOR), or faropenem (FAR). Higher mutation frequencies are associated with ertapenem and faropenem treatment, while lower mutation frequencies are observed with meropenem treatment. In MGH32, an isolate without β-lactamase genes, only faropenem resistant mutants were isolated. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis to compare between ertapenem treatment and other carbapenems or faropenem. (B) Mutation frequencies of UCI38 and Mut34, an ertapenem-restricted-resistant mutant derived from UCI38, under treatment with meropenem. Despite having the same MIC of meropenem as UCI38, Mut34 had higher mutation frequencies than UCI38. (C, D) Relative expression levels of blaSHV-12 (C) or ompK36 (D) in UCI38, Mut34, and Mut186 (an ertapenem and meropenem-resistant mutant derived from Mut34) show the progressive acquisition of mutations to achieve meropenem resistance. Mut34 has increased blaSHV-12 relative to its parent UCI38; Mut186 has disrupted ompK36, relative to its parent Mut34. (E) Conjugation efficiencies of UCI38, Mut34, and Mut186 with K. pneumoniae clinical isolate BIDMC45 carrying blaKPC-2. In the presence of meropenem, Mut186 had the highest conjugation efficiency with UCI38 having the lowest. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis to compare UCI38 with other strains. Error bars are plotted as standard deviation. The limit of detection is indicated with a dashed line, and the asterisk (*) under the dashed line indicates frequencies under the limit of detection.

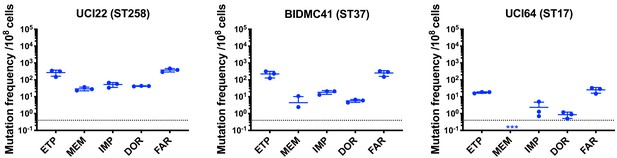

Mutation frequencies of three other isolates under separate treatment with ertapenem (ETP), meropenem (MEM), imipenem (IMP), doripenem (DOR), or faropenem (FAR).

Experiments were repeated three times, and error bars were plotted as standard deviation.

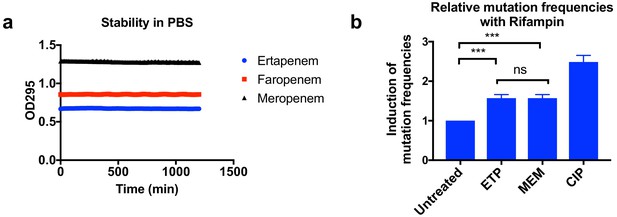

Higher mutation frequencies associated with ertapenem were not due to stability of these drugs or to the induction of mutagenesis.

(a) Stability of ertapenem (ETP), faropenem, and meropenem (MEM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Antibiotics were diluted to 0.5 mM in PBS, and 100 µl of each antibiotic was used for the assay. OD295 was measured every 10 min for 20 hr. These three antibiotics are stable for at least 20 hr in our assay condition. (b) Induction of mutation frequencies under treatment with rifampicin. Bacterial cultures of UCI38 in 384-well plates were pre-treated with ETP, MEM, or ciprofloxacin (CIP) at 0.1× MICs of each drug for 2 hr, then mutation frequencies with rifampicin treatment (50 µg/ml) were measured using the modified Luria–Delbrück system. ETP and MEM induced mutagenesis to the same degree. Data is plotted as the average of three experiments. Error bars are plotted as the standard deviation. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis to compare the untreated cultures with cultures treated with ETP or MEM.

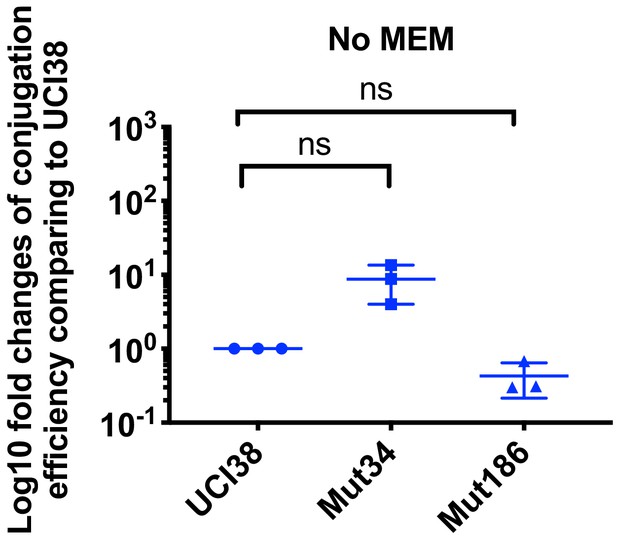

Conjugation efficiencies of UCI38, Mut34, and Mut186 (derived from Mut101 with meropenem treatment) with a K. pneumoniae clinical isolate BIDMC45 carrying blaKPC-2.

The conjugation process was conducted in the absence of meropenem. No significant difference was observed in the absence of meropenem between UCI38 and Mut34 (p=0.11) or between UCI38 and Mut186 (p=0.16). All experiments were repeated three time. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis to compare between the mutant and the ancestor strain UCI38. Error bars are plotted as standard deviation.

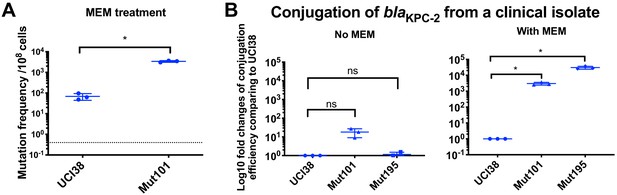

Prior exposure to faropenem promotes the evolution of meropenem resistance.

(A) Mutation frequencies of UCI38 and Mut101 under treatments with meropenem at the concentration of 1.1× MIC (0.067 g/ml). Mut101 is a mutant of UCI38 derived from faropenem treatment with the same MIC of meropenem as UCI38 and increased MIC of ertapenem. Mut101 showed significantly higher mutation frequencies than these of the UCI38 with meropenem treatment. (B) Conjugation efficiencies of UCI38, Mut101and Mut195 (derived from Mut101 with meropenem treatment) with a K. pneumoniae clinical isolate BIDMC45 carrying blaKPC-2. The conjugation process was conducted in the absence or presence of meropenem (0.003 g/ml). In the presence of meropenem, Mut101 and Mut196 showed higher conjugation efficiencies than these of UCI38. No significant difference was observed in the absence of meropenem between UCI38 and Mut101 (p=0.08) or between UCI38 and Mut195 (p=0.5). All experiments were repeated three time. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis to compare the mutation frequencies (A) or conjugation efficiencies (B) between the mutant and the ancestor strain UCI38. Error bars are plotted as standard deviation.

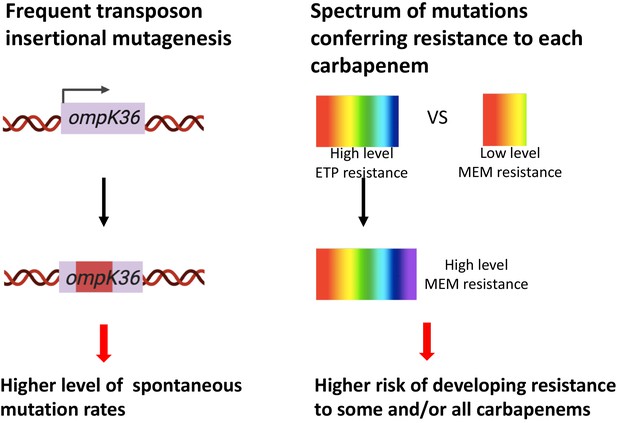

Two genetic determinants of the evolution of carbapenem resistance were identified from this study.

On the one hand, high-level transposon insertional mutagenesis facilitates the inactivation of porin genes. On the other hand, a broader spectrum of genetic mutation conferring resistance to ertapenem leads to higher rates of developing resistance with ertapenem treatment; these ertapenem-restricted resistance mutations can serve as stepping-stones to facilitate the development of high-level resistance to all carbapenems.

Tables

Genetic features of 10 selected carbapenem-susceptible clinical isolates.

| Strains | ST | MIC (µg/ml) of | Narrow-spectrum β-lactamase | ESBL | Carbapenemase | ompK36 | Accession no. | CRISPR system | R-M system | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETP | MEM | |||||||||

| UCI38 | ST258 | 0.25 | 0.06 | None | blaSHV-12 | None | Intact | GCA_000566805.1 | No | Type II; Type III |

| MGH222 | ST15 | 0.03 | 0.03 | None | blaSHV-28 | None | Intact | GCA_014902955.1 | Yes | None |

| UCICRE126 | ST147 | 0.03 | 0.25 | blaSHV-11 | None | None | Intact | GCA_014902315.1 | Yes | Type I |

| MGH66 | ST29 | 0.06 | 0.03 | blaSHV-187 | None | None | Intact | GCA_000694555.1 | No | Type II |

| BIDMC41 | ST37 | 2 | 0.06 | blaTEM-1 | blaSHV-12 | None | Intact | GCA_000492195.1 | No | Type II |

| MGH74 | ST76 | 0.03 | 0.06 | blaSHV-1 | None | None | Intact | GCA_000694715.1 | No | Type I; Type II |

| MGH158 | ST152 | 0.03 | 0.06 | blaSHV-1 | None | None | Intact | GCA_002152555.1 | No | None |

| UCI64 | ST17 | 0.03 | 0.03 | blaSHV-11 | None | None | Intact | GCA_000688175.1 | No | Type I |

| UCI34 | ST34 | 0.06 | 0.03 | blaSHV-26 | None | None | Intact | GCA_000566845.1 | Yes | None |

| MGH21 | ST111 | 0.03 | 0.03 | blaSHV-11 | None | None | Intact | GCA_000492915.1 | Yes | None |

Characterization of representative mutants resistant to both ertapenem and meropenem or to ertapenem alone.

| Mutant ID | Ancestor | Mutations causing decreased susceptibility | Gene function | Fold changes of MICs compared to ancestor strains | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETP | MEM | ||||

| Mutants resistant to ertapenem alone | |||||

| Mut87 | MGH21 | wzc (L367_02683): c.381delA | Exopolysaccharide biosynthesis | 2 | 1 |

| Mut86 | MGH21 | ompA (L367_001084): p.G31D | Porin | 2 | 1 |

| Mut131 | MGH21 | ompK36 (L367_002817), c.332_333insTACGACCGTAGT | Porin | 256 | 1 |

| Mut101 | UCI38 | rseA (P841_001338):: IS1 | Anti-sigma E factor, involved in maintaining cell envelope integrity | 8 | 1 |

| Mut34 | UCI38 | blaSHV-12 (P841_005417) dup[2] | ESBL | 8 | 1 |

| Mutants resistant to ertapenem and meropenem | |||||

| Mut21 | MGH21 | bamD (L367_003146): c.-4C > T | Outer membrane protein assembly factor | 8 | 2 |

| Mut136 | MGH21 | omp36K (L367_002817): p.Q311STP | Porin | 64 | 8 |

| Mut41 | UCI38 | ompK36 (P841_001022):: IS1 | Porin | 64 | 8 |

| Mut107 | UCI38 | ompK36 (P841_001022):: IS5 | Porin | 64 | 16 |

| Mut45 | UCI38 | ompK36 (P841_001022):: IS91 | Porin | 64 | 16 |

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCI38 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000566805.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH222 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_014902955.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCICRE126 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_014902315.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH66 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000694555.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH74 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000694715.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH158 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_002152555.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH21 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000492915.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH32 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000493075.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate in which the native blaSHV-1 was inactivated by a point mutation (Leu88STP) |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCI43 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000566745.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCI22 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000566925.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCI44 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000566725.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCI34 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000566845.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH30 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000492935.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | BIDMC40 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000492215.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCI64 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000688175.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | BIDMC41 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000492195.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | BWH41 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000567545.1 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH21SHV | This study, available upon request | MGH21SHV | MGH21(pSHV), MGH21 expressing blaSHV-12 |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH21∆cas | This study, available upon request | MGH21∆cas | MGH21 in which the operon encoding the CRISPR-Cas system was deleted |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH21∆cas(pESBL) | This study, available upon request | MGH21∆cas(pESBL) | MGH21Δcas carrying pESBL isolated from UCI38 |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH21∆cas(pCas) | This study, available upon request | MGH21∆cas(pCas) | MGH21Δcas expressing CRISPR-Cas system through two lab constructs |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | MGH21∆cas(pVector) | This study, available upon request | MGH21∆cas(pVector) | MGH21Δcas carrying two empty vectors |

| Strain, strain background (E. coli) | E. coli 10ß | NEB (C3020) | Cat # C3020 | E. coli strain from NEB |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut34 | This study, available upon request | Mut34 | Mutant of UCI38 from ertapenem treatment, with the blaSHV-12 duplication |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut101 | This study, available upon request | Mut101 | Mutant of UCI38 from faropenem treatment, ompK36 is down-regulated due to the inactivation of rseA |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut186 | This study, available upon request | Mut186 | Mutant of Mut34 from meropenem treatment, with both blaSHV-12 duplication and ompK36 inactivation |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut195 | This study, available upon request | Mut195 | Mutant of Mut101 from meropenem treatment, with both blaSHV-12duplication and ompK36 down-regulation |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | UCI38R | This study, available upon request | UCI38R | Rifampin resistant version of UCI38 |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut34R | This study, available upon request | Mut34R | Rifampin resistant version of Mut34 |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut101R | This study, available upon request | Mut101R | Rifampin resistant version of Mut101 |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut186R | This study, available upon request | Mut186R | Rifampin resistant version of Mut186 |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | Mut195R | This study, available upon request | Mut195R | Rifampin resistant version of Mut195 |

| Strain, strain background (K. pneumoniae) | BIDMC45 | Cerqueira et al., 2017 | GCA_000567025 | A K. pneumoniae clinical isolate carrying blaKPC-2 |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pSHV (plasmid) | This study, available upon request | pSHV | blaSHV-12, including upstream 500 bp, was amplified from UCI38, and blunt ligated into pSmart_LCKN (KanamycinR) |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pKOV (plasmid) | Addgene | RRID:Addgene_25769 | The plasmid used for gene knockout though homologous recombination, ChloramphenicolR |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pKOV-casKO (plasmid) | This study, available upon request | pKOV-casKO | A 2 kb DNA fusion containing 1 kb upstream and 1 kb downstream of cas operon in MGH21 was ligated into pKOV using BamHI and NotI sites, ChloramphenicolR |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pBAD33Gm (plasmid) | This study, available upon request | pBAD33Gm | pBAD33 with Gentamycin resistance, a gentamycin resistance gene was ligated into HindIII cloning site on pBAD33 (GentamycinR, ChloramphenicolR) |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pBAD33Gm_CasCRISPR1 (plasmid) | This study, available upon request | pBAD33Gm_CasCRISPR1 | CasABECD, cas1, cas2 operon, and CRISPR array I was amplified from MGH21, a SD sequence was incorporated upstream of ATG of casA, then this piece of DNA was ligated into KpnI and XbaI sites on pBAD33Gm (GentamycinR, ChloramphenicolR) |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pCas3CRISPR2 (plasmid) | This study, available upon request | pCas3CRISPR2 | Cas3 gene, including the upstream 500 bp region and CRISPR array II region, was amplified from MGH21 and ligated into pSmart LC KN, KanamycinR |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pBAD33 (plasmid) | Guzman et al., 1995 | pBAD33 | Cloning vector, ChloramphenicolR |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | pSmart LC KN (vector) | Lucigen | Cat. # 40821 | Cloning vector, KanamycinR |

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp1-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 2

Number of beta-lactamase genes in 267 K. pneumoniae.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp2-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 3

CRISRP-Cas systems and R-M systems in 267 K. pneumoniae.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp3-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 4

The presence or absence of CRISPR-Cas systems in 2453 K. pneumoniae strains.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp4-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 5

Spacer sequences in MGH21.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp5-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 6

Prevalence of spacer-hit genes in plasmid sequences.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp6-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 7

ResFinder results of plasmids containing spacer11-hit gene.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp7-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 8

ResFinder results of plasmids containing spacer24-hit gene.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp8-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 9

Numbers of mutants with mutations (SNP/Short INDEL vs. TN insertion) in ompK36.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp9-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 10

ISs involved in inactivating ompK36 in UCI38.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp10-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 11

MICs and fold changes of MICs measured from 90 mutants.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp11-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 12

Validation of mutations causing decreased susceptibility.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp12-v2.xlsx

-

Supplementary file 13

Primers used in this study.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-supp13-v2.xlsx

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/67310/elife-67310-transrepform-v2.docx