Cardiovascular disease and subsequent risk of psychiatric disorders: a nationwide sibling-controlled study

Figures

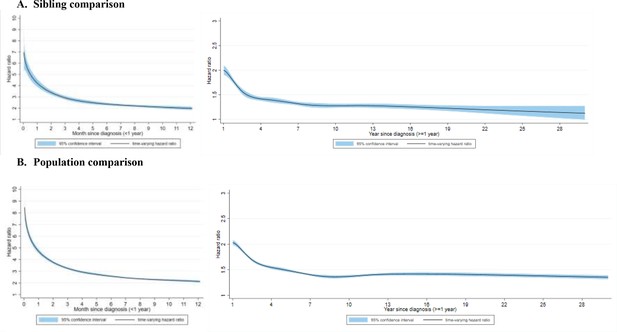

Time-varying hazard ratios for an incident psychiatric disorder among CVD patients, compared with their unaffected full siblings (sibling comparison) or matched population controls (population comparison), by time of follow-up (<1 and ≥1 year from CVD diagnosis)*.

(A) Sibling comparison. (B) Population comparison. *CVD: cardiovascular disease. Time-varying hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were derived from flexible parametric survival models, allowing the effect of psychiatric disorder to vary over time. A spline with 5 df was used for the baseline rate, and 3 df was used for the time-varying effect. All models were adjusted for age at index date, sex, educational level, yearly individualized family income, cohabitation status, history of somatic diseases, as well as family history of psychiatric disorder (for population comparison). P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

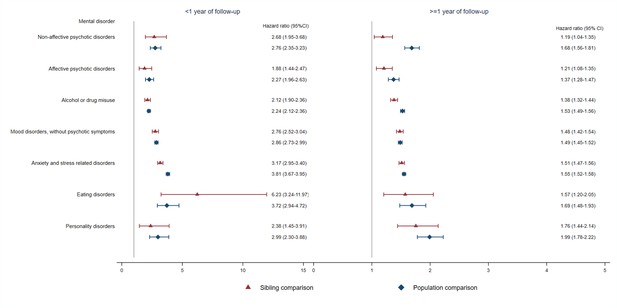

Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for different types of psychiatric disorder among CVD patients compared with their full siblings and matched population controls, by time of follow-up (<1 or ≥ 1 year from CVD diagnosis)*.

*CVD: cardiovascular disease. Cox regression models were stratified by family identifier for sibling comparison or matching identifier (birth year and sex) for population comparison, controlling for age at index date, sex, educational level, individualized family income, cohabitation status, history of somatic diseases, and family history of psychiatric disorder (in population comparison). Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

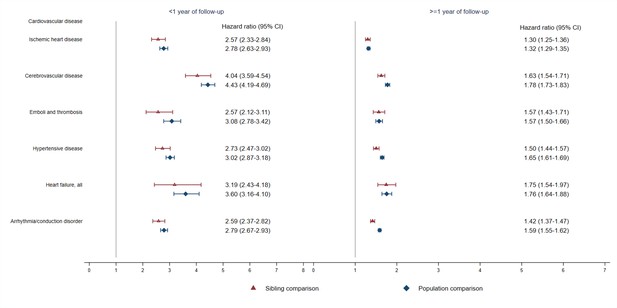

Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for psychiatric disorders among different groups of CVD patients compared with their full siblings and matched population controls, by time of follow-up (<1 or ≥ 1 year from CVD diagnosis)*.

*CVD: cardiovascular disease. Cox regression models were stratified by family identifier for sibling comparison or matching identifier (birth year and sex) for population comparison, controlling for age at index date, sex, education level, individualized family income, cohabitation status, history of somatic diseases, and family history of psychiatric disorder (in population comparison). Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. We identified all cardiovascular diagnoses during follow-up and considered CVD comorbidity as a time-varying variable by grouping the person-time according to each diagnosis. P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

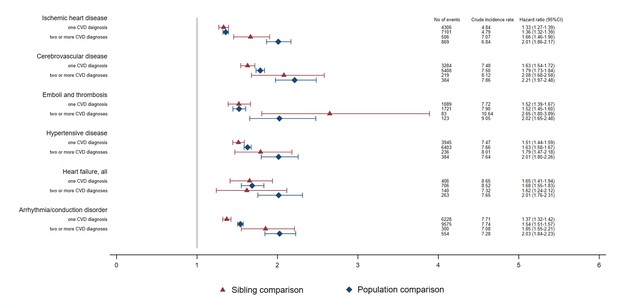

Crude incidence rates and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for an incident psychiatric disorder among different types of CVD patients compared with their full siblings or matched population controls, by number of CVD diagnoses during ≥1 year of follow-upa.

CVD: cardiovascular disease. aCox regression models, stratified by family identifier for sibling comparison or matching identifier (birth year and sex) for population comparison, and controlled for educational level, individualized family income, cohabitation status, as well as sex and birth year (in sibling comparison). Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. For patients with two or more CVD diagnoses, follow-up time started from diagnosis of that cardiovascular comorbidity. P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

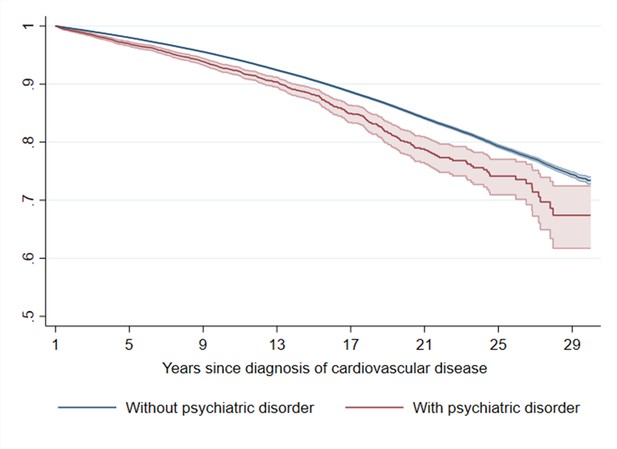

Estimated Kaplan–Meier curves of CVD death in CVD patients with and without incident psychiatric disorder during the first year of follow-upa.

aCVD: cardiovascular disease. Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. 90.4% of CVD patients (N = 785,287) survived the first year of follow-up and included in this analysis. P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

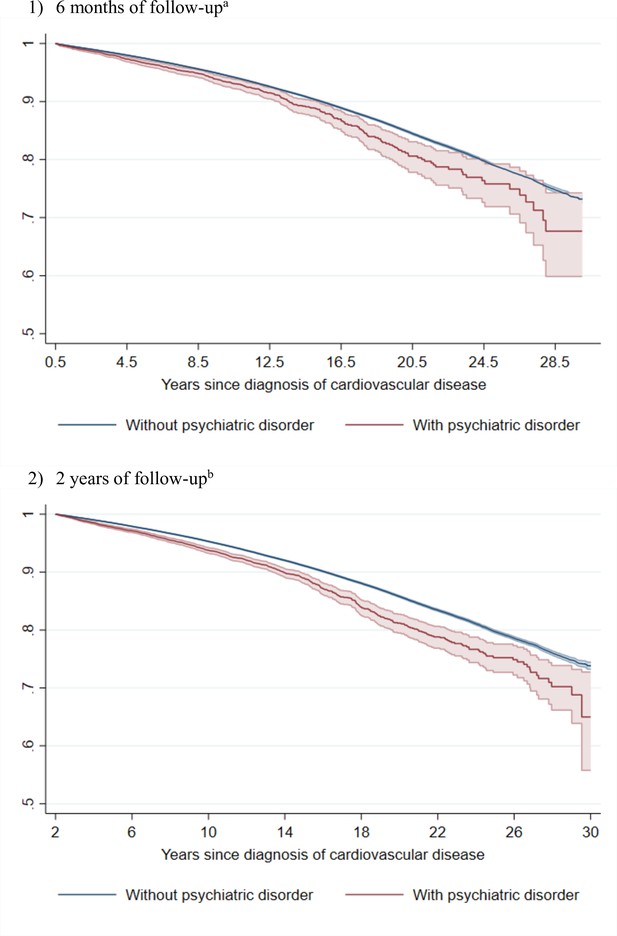

Estimated Kaplan–Meier curves of CVD death in CVD patients with and without incident psychiatric disorder during (1) 6 months or (2) 2 years of follow-up.

CVD: cardiovascular disease. aTime since index date was used as underlying time scale. 94.1% of CVD patients (N = 817,748) survived the 6 months of follow-up and included in this analysis. The hazard ratio of cardiovascular death was 1.40 (95% confidence interval, 1.27–1.54) when comparing CVD patients with psychiatric disorder to patients without such a psychiatric diagnosis (mortality rate, 8.1 and 7.0 per 1000 person-years, respectively). bTime since index date was used as underlying time scale. 83.8% of CVD patients (N = 728,179) survived the 2 years of follow-up and included in this analysis. The hazard ratio of cardiovascular death was 1.52 (95% confidence interval, 1.43–1.62) when comparing CVD patients with psychiatric disorder to patients without such a psychiatric diagnosis (mortality rate, 9.1 and 7.4 per 1000 person-years, respectively). P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

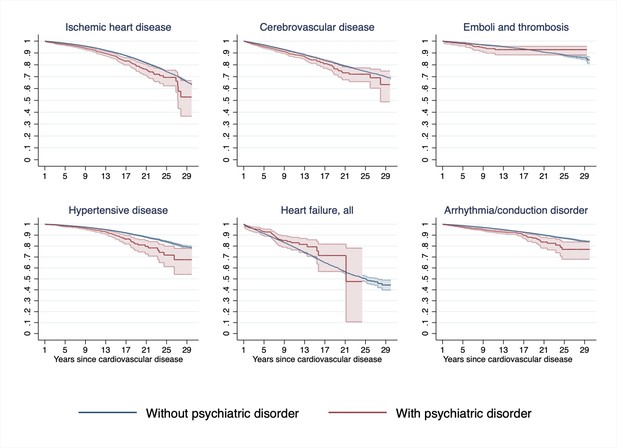

Estimated Kaplan–Meier curves of CVD death in CVD patients with and without incident psychiatric disorder during the first year of follow-up, according to types of first CVD diagnosisa.

CVD: cardiovascular disease. aTime since index date was used as underlying time scale. 90.4% of CVD patients (N = 785,287) survived the first year of follow-up and included in this analysis. P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

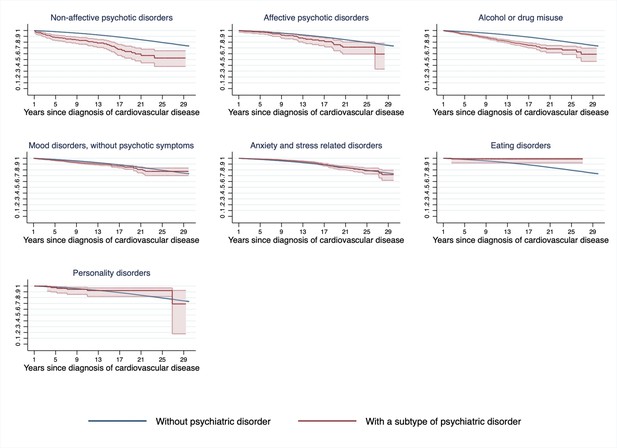

Estimated Kaplan–Meier curves of CVD death in CVD patients with and without incident psychiatric disorder during the first year of follow-up, according to types of incident psychiatric disordera.

CVD: cardiovascular disease. aTime since index date was used as underlying time scale. 90.4% of CVD patients (N = 785,287) survived the first year of follow-up and included in this analysis. P<0.05 was considered level of significance.

Tables

Characteristics of CVD patients diagnosed in Sweden between 1987 and 2016, their unaffected siblings and matched population controls.

| Characteristics | Sibling comparison | Population comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD patients (N = 509,467) | Unaffected full siblings (N = 910,178) | CVD patients (N = 869,056) | Matched population controls (N = 8,690,560) | |

| Median age at index date in years (IQR) | 57 (48–65) | 55 (46–63) | 60 (51–68) | 60 (51–68) |

| Median follow-up time in years (IQR) | 8.1 (3.7–13.7) | 8.1 (3.8–13.7) | 7.7 (3.3–13.2) | 7.1 (3.2–12.4) |

| Male sex | 308,203 (60.5) | 440,177 (48.4) | 514,388 (59.2) | 5,143,880 (59.2) |

| Educational level | ||||

| <9 years | 149,555 (29.4) | 261,752 (28.8) | 272,960 (31.4) | 2,294,482 (26.4) |

| 9–12 years | 225,548 (44.3) | 413,702 (45.5) | 376,917 (43.4) | 3,548,338 (40.8) |

| >12 years | 134,364 (26.4) | 234,724 (25.8) | 219,179 (25.2) | 2,847,740 (32.8) |

| Yearly individualized family income level | ||||

| Top 20% | 107,990 (21.2) | 175,658 (19.3) | 139,098 (16.0) | 1,757,726 (20.2) |

| Middle | 301,706 (59.2) | 549,842 (60.4) | 535,109 (61.6) | 5,152,938 (59.3) |

| Lowest 20% | 99,485 (19.5) | 184,588 (20.3) | 192,858 (22.2) | 1,706,931 (19.6) |

| Unknown | 286 (0.1) | 90 (0.0) | 1991 (0.2) | 72,965 (0.8) |

| Cohabitation status | ||||

| Non-cohabitating | 223,134 (43.8) | 392,256 (43.1) | 373,337 (43.0) | 3,744,116 (43.1) |

| Cohabitating | 286,047 (56.2) | 517,832 (56.9) | 493,728 (56.8) | 4,873,479 (56.1) |

| Missing | 286 (0.1) | 90 (0.0) | 1991 (0.2) | 72,965 (0.8) |

| History of somatic disease* | 71,273 (14.0) | 79,679 (8.8) | 135,473 (15.6) | 955,030 (11.0) |

| Family history of psychiatric disorder† | 133,094 (26.1) | 251,237 (27.6) | 209,957 (24.2) | 2,003,161 (23.1) |

| Type of first-onset CVD | ||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 122,084 (24.0) | – | 212,737 (24.5) | – |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 71,030 (13.9) | – | 126,860 (14.6) | – |

| Emboli and thrombosis | 25,338 (5.0) | – | 42,857 (4.9) | – |

| Hypertensive disease | 89,818 (17.6) | – | 150,337 (17.3) | – |

| Heart failure | 15,726 (3.1) | – | 30,469 (3.5) | – |

| Arrhythmia/conduction disorder | 126,738 (24.9) | – | 210,654 (24.2) | – |

| Others | 58,733 (11.5) | – | 95,142 (11.0) | – |

| Number of cardiovascular diagnoses during follow-up | ||||

| One | 365,266 (71.7) | – | 605,615 (69.7) | – |

| Two | 99,921 (19.6) | – | 179,472 (20.7) | – |

| Three or more | 44,280 (8.7) | – | 83,969 (9.7) | – |

-

*

History of somatic diseases included chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, diabetes, renal diseases, liver diseases, ulcer diseases, and HIV infection/AIDS that diagnosed before index date.

-

†

The difference between exposed patients and unaffected full siblings was due to different number of siblings for exposed patients. The family history of psychiatric disorder was constant within each family.

-

IQR: interquartile range. CVD: cardiovascular disease.

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

(a) Summary of prospective cohort studies addressing the association between various indications of cardiovascular disease and risk of psychiatric disorders/psychiatric symptoms. (b) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for exposure, outcome, and covariates identifications. (c) Crude incidence rates (IRs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incident psychiatric disorder among CVD patients compared with their full siblings or matched population controls, by patient characteristics. CVD: cardiovascular disease. aCox regression models, stratified by family identifier for sibling comparison or matching identifier (birth year and sex) for population comparison, adjusting for sex, birth year, educational level, individualized family income, cohabitation status, history of somatic disease, and family history of psychiatric disorder. Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. (d) Crude incidence rates (IRs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incident psychiatric disorders among CVD patients compared with their full siblings or matched population controls, by time of follow-up (<1 or ≥ 1 year from CVD diagnosis). CVD: cardiovascular disease. aCox regression models, stratified by family identifier for sibling comparison or matching identifier (birth year and sex) for population comparison. Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. (e) Crude incidence rates (IRs) of different types of psychiatric disorder among CVD patients, their full siblings, and matched population controls, by time of follow-up (<1 or ≥ 1 year from CVD diagnosis). CVD: cardiovascular disease. (f) Crude incidence rates (IRs) for psychiatric disorders among different groups of CVD patients, their full siblings and matched population controls, by time of follow-up (<1 or ≥ 1 year from CVD diagnosis)a. CVD: cardiovascular disease. aWe identified all cardiovascular diagnoses during follow-up and considered CVD comorbidity as a time-varying variable by grouping the person-time according to each diagnosis. (g) Crude incidence rates (IRs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for psychiatric disorders among CVD patients compared with their full siblings or matched population controls, excluding CVD patients medicated with psychotropic drugs, by time of follow-up (<1 or ≥1 year from CVD diagnosis)a. CVD: cardiovascular disease. aCVD patients diagnosed during 2006–2016 were included in this analysis due to the availability of data on prescribed drug. In sibling comparison, 27.8% CVD patients and 23.5% siblings were excuded due to prior medicaiton of psychotropic drugs before index date. In population comparison, 30.6% CVD patients and 25.0% population controls were excluded due to prior medicated with psychotropic drugs before index date. bCox regression models, stratified by family identifier for sibling comparison or matching identifier (birth year and sex) for population comparison. Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. Definition of psychiatric disorder included hospital visits as well as use of psychotropic drugs during follow-up. (h) Crude incidence rates (IRs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incident psychiatric disorder among CVD patients compared with their full siblings or matched population controls, restricting study period to 2001–2016 and excluding individuals with a history of alcoholic cirrhosis of liver or COPD, by time of follow-up (<1 or ≥1 year from CVD diagnosis). COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. §In sibling comparison, 1.14% exposed patients and 0.55% siblings were excluded due to a history of alcoholic cirrhosis or COPD before index date. In population comparison, 1.44% exposed patients and 1.01% population controls were excluded due to having a history of alcoholic cirrhosis or COPD before index date. *Cox regression models, stratified by family identifier for sibling comparison or matching identifier (birth year and sex) for population comparison. Time since index date was used as underlying time scale. Definition of psychiatric disorder included hospital visits as well as use of psychotropic drugs during follow-up.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/80143/elife-80143-supp1-v2.docx

-

Supplementary file 2

Study design.

CVD: cardiovascular disease. *67,745 families had more than one sibling affected by CVD.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/80143/elife-80143-supp2-v2.docx

-

MDAR checklist

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/80143/elife-80143-mdarchecklist1-v2.docx