The forgotten people: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection as a priority for the inclusion health agenda

Figures

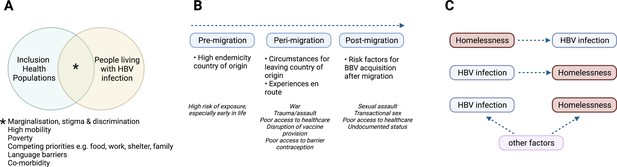

Characteristics of HBV in inclusion health populations.

(A) Illustration of the overlapping characteristics that may be present among different inclusion populations and people living with HBV infection. (B) Relationship between migrancy and asylum-seeking status as a risk factor for HBV infection. (C) Representation of complex relationship between HBV infection and PEH, where other factors include for example injecting drug use, transactional sex, mental illness (Freeland et al., 2021; Ly et al., 2021a). HBV – hepatitis B virus; PEH - People experiencing homelessness. Figure created in BioRender.com with a licence to publish.

Solutions for service development to overcome barriers for people living with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in inclusion health populations, applying framework suggested by Charania et al., 2020.

Figure created in BioRender.com with a licence to publish.

Tables

Top 20 origins of international migrants in 2020 (millions), HBV prevalence and progress towards SDG 30 goals for elimination of HBV as a public health threat.

Data - United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2020b). International Migrant Stock 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock; The Polaris Observatory, CDA Foundation; https://cdafound.org/polaris-countries-compare/. HBV – Hepatitis B virus. SDG – Sustainable Development Goal.

| Country of Origin | Number of International Migrants (millions) | HBV Prevalence* | 90% Diagnosed† | 80% Treated† | 65% Reduction in Mortality† | Reduced Prevalence in 5 year olds† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 17.9 | 3% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2032 |

| Mexico | 11.2 | 0% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2015 |

| Russia | 10.8 | 1% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2015 |

| China | 10.5 | 6% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2021 |

| Syria | 8.5 | 6% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 |

| Bangladesh | 7.4 | 5% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2043 |

| Pakistan | 6.3 | 1% | 2042 | 2051 | 2051 | 2036 |

| Ukraine | 6.1 | 1% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2030 |

| Philippines | 6.1 | 10% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 |

| Afghanistan | 5.9 | 3% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2045 |

| Venezuela | 5.4 | 1% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2031 |

| Poland | 4.8 | 1% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2015 |

| United Kingdom | 4.7 | 1% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2020 |

| Indonesia | 4.6 | 7% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 |

| Kazakhstan | 4.2 | 4% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2027 |

| Palestine | 4.0 | 2% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2015 |

| Romania | 4.0 | 3% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2025 |

| Germany | 3.9 | 0% | 2039 | 2051 | 2051 | 2015 |

| Myanmar | 3.7 | 8% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 |

| Egypt | 3.6 | 1% | 2051 | 2051 | 2051 | 2018 |

-

*

Green -Low HBV prevalence (<2%); Amber - intermediate HBV prevalence (2–8%); Red - high HBV (prevalence >8%).

-

†

Green - HBV SDG reached before 2030; Amber - SDG reached 2031–50; Red - SDG reached >2050.

Key review and study observations pertinent to HBV infection among inclusion health populations.

| Inclusion health population | Citation | Study type | Country | Key observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEH, PWID, Incarcerated individuals, sex workers | Aldridge et al., 2018 | Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | High-income countries |

|

| PWID, PEH, Previous incarceration | Taylor et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional | UK |

|

| Migrants | Prestileo et al., 2022 | Cross-sectional | Italy |

|

| Colucci et al., 2022 | Cross-sectional | Italy | Increased risk of BBV acquisition persisted after arrival in Italy, possibly due to living conditions, sex work, lack of access to healthcare and social support | |

| Mazzitelli et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional | Italy |

| |

| Armitage et al., 2022 | Cross-sectional | UK |

| |

| Williams et al., 2020a | Cross-sectional | UK |

| |

| Eborall et al., 2020 | Qualitative | UK |

| |

| Tasa et al., 2021 | Retrospective cohort | Finland |

| |

| Bierhoff et al., 2021 | Mixed-methods | Thailand |

| |

| PEH | Ly et al., 2021a | Narrative review | Global |

|

| Al Shakarchi et al., 2020 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Global |

| |

| PWID | Degenhardt et al., 2017 | Multistage systematic review | Global |

|

| People who misuse alcohol | Magri et al., 2020 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Global |

|

| Incarcerated people | Dolan et al., 2016 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Global |

|

| Nakitanda et al., 2021 | Descriptive analysis | Europe |

| |

| Kamarulzaman et al., 2016 | Narrative review | Global |

| |

| Dana et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | Iran |

| |

| Sex workers | Schuelter-Trevisol et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | Brazil |

|

| Miranda et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional | Brazil |

| |

| Matos et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional | Brazil |

| |

| Leuridan et al., 2005 | Cross-sectional | Belgium |

| |

| Mak et al., 2003 | Cross-sectional | Belgium |

| |

| Dos Ramos Farías et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional | Argentina |

| |

| Todd et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | Afghanistan |

| |

| Jeal and Salisbury, 2004 | Cross-sectional | UK |

| |

| Bitty-Anderson et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional | Togo |

| |

| Roma and Traveller populations | Macejova et al., 2020 | Cross-sectional | Slovakia |

|

| Gregory et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional | UK |

| |

| Veselíny et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional | Slovakia |

| |

| Indigenous Populations | Davies et al., 2019 | Cross-sectional | Australia |

|

| Qama et al., 2021 | Retrospective cohort | Australia |

| |

| Einsiedel et al., 2013 | Retrospective cohort | Australia |

| |

| Osiowy et al., 2013 | Narrative review | USA, Canada, Greenland |

| |

| Russell et al., 2019 | Systematic review | Latin America |

|

-

SMR Standardised Mortality Ratio; aOR adjusted odds ratio; OR odds ratio; RR relative risk; CI confidence interval; HBV hepatitis B virus; UI Uncertainty Interval; MSM men who have sex with men; PEH people experiencing homelessness, PWID people who inject drugs; UASC unaccompanied asylum-seeking children; HBsAg Hepatitis B surface antigen (active HBV infection); HBc Hepatitis B core antibody