bMERB domains are bivalent Rab8 family effectors evolved by gene duplication

Abstract

In their active GTP-bound form, Rab proteins interact with proteins termed effector molecules. In this study, we have thoroughly characterized a Rab effector domain that is present in proteins of the Mical and EHBP families, both known to act in endosomal trafficking. Within our study, we show that these effectors display a preference for Rab8 family proteins (Rab8, 10, 13 and 15) and that some of the effector domains can bind two Rab proteins via separate binding sites. Structural analysis allowed us to explain the specificity towards Rab8 family members and the presence of two similar Rab binding sites that must have evolved via gene duplication. This study is the first to thoroughly characterize a Rab effector protein that contains two separate Rab binding sites within a single domain, allowing Micals and EHBPs to bind two Rabs simultaneously, thus suggesting previously unknown functions of these effector molecules in endosomal trafficking.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18675.001Introduction

Rab proteins, the biggest subfamily within the superfamily of small GTPases, are major regulators of vesicular trafficking in eukaryotic cells (Takai et al., 2001). Like all small GTPases, Rab proteins cycle between an inactive GDP-bound and an active GTP-bound state. The cycling is tightly regulated and mediated by two families of enzymes: guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) that catalyze the GDP/GTP exchange and GTPase activating proteins that stimulate GTP hydrolysis (Stenmark, 2009). Additionally, a variety of different effector proteins interact specifically with GTP-bound Rab proteins and mediate their versatile physiological roles in membrane trafficking, including budding of vesicles from a donor membrane, directed transport through the cell and finally tethering and fusion with a target membrane (Grosshans et al., 2006). Especially in long-distance vesicular transport processes (e.g. in neuronal axons and dendrites), directed vesicular transport along cytoskeletal tracks appears to be an obvious mechanism and, consistently, different effector proteins have been reported to link Rab proteins to the cytoskeleton (Kevenaar and Hoogenraad, 2015; Horgan and McCaffrey, 2011).

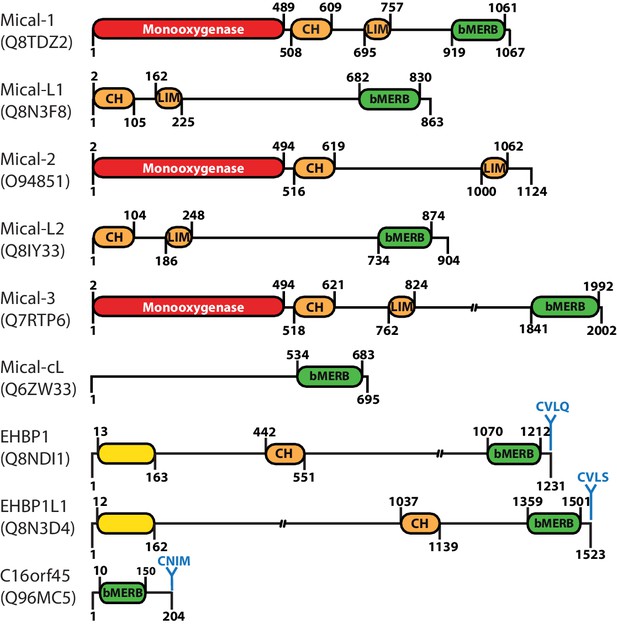

One such family of effector proteins that was reported to link Rab proteins and the cytoskeleton is the Mical (molecules interacting with CasL) family (Figure 1) (Fischer et al., 2005). Most of these Mical proteins contain an N-terminal monooxygenase domain that was reported to regulate actin dynamics via reversible oxidation of a methionine residue (Hung et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013; Hung et al., 2013). Additionally, all Mical proteins except the Mical C-terminal like protein (Mical-cL) contain a calponin homology (CH) and a Lin11, Isl-1 and Mec-3 (LIM) domain that have been reported to assist the interaction with actin and other cytoskeletal proteins, respectively (Giridharan and Caplan, 2014). Finally, all except Mical-2 contain a C-terminal coiled-coil domain that is also termed domain of unknown function (DUF) 3585 and that is known to interact with different Rab proteins (Giridharan and Caplan, 2014) (Figure 1).

Domain architecture of human proteins containing bMERB domains.

Besides their C-terminal RBD (referred to as bivalent Mical/EHBP Rab binding (bMERB) domain), most Mical proteins contain an N-terminal Monooxygenase (red), a CH- and a LIM-domain (both orange). EHBPs also contain an actin binding CH-domain and an N-terminal membrane binding C2-domain (yellow) as well as a C-terminal prenylation motif (CaaX-box) following the bMERB domain. Two proteins predicted to contain only the bMERB domains (Mical-cL and C16orf45) are also shown. For proteins with multiple known splice variants, domain boundaries are indicated for isoform 1 (Mical-1: Uniprot ID Q8TDZ2, genomic location 6q21; Mical-L1: Uniprot ID Q8N3F8, genomic location 22q13.1; Mical-L2: Uniprot ID Q8IY33, genomic location 7p22.3; Mical-3: Uniprot ID Q7RTP6, genomic location 22q11.21; Mical-cL: Uniprot ID Q6ZW33, genomic location 11p15.3; EHBP1: Uniprot ID Q8NDI1, genomic location 2p15; EHBP1L1 Uniprot ID Q8N3D4, genomic location 11q13.1). The reader is referred to the main text for further details.

According to the SMART database (Schultz et al., 1998), this largely uncharacterized DUF3585 domain is present in more than 450 eukaryotic proteins (including 8 human proteins, see Figure 1). In humans, besides the Mical proteins this includes the family of EH (Eps15-homology) domain binding proteins (EHBPs) and one uncharacterized protein (C16orf45; see Figure 1). Interestingly, the EHBPs also contain a CH-domain and have been described to couple vesicular transport to the actin cytoskeleton (Shi et al., 2010; Guilherme et al., 2004).

Hitherto, the structural basis and the specificity of interaction between the Rab binding domains of Micals/EHBPs and Rab proteins remained largely unknown. In this publication, we have characterized the interaction of a number of these domains with Rab proteins extensively. Our results indicate preferential binding of this family of effector proteins to Rab proteins of the Rab8 family. Additionally, the results show that at least some of these effector domains can bind two Rab proteins simultaneously, suggesting a possible role as a Rab hub in vesicular trafficking.

In order to understand the structural basis of the interaction, we solved the first x-ray crystallographic structure of the RBD from the human protein Mical-3 and the first structures of different Rab proteins in complex with the RBDs of Mical-cL in a 1:1 stoichiometry and of Rab10 and the RBD of Mical-1 in a 2:1 stoichiometry.

This study is the first to show the structural basis of Rab proteins interacting with these RBDs and to systematically characterize the interaction with Rab proteins. Analysis of our data suggests that the second Rab binding site of these RBDs has evolved via a gene duplication event, indicating intriguing and hitherto unknown mechanisms of a concerted action of different Rab-regulated trafficking steps connected by these bivalent effector proteins, which we refer to as “bivalent Mical/EHBP Rab binding” (bMERB) domains (Figure 1). The study therefore substantially increases our understanding of Rab:effector interactions and will aid future research regarding the function of this diverse effector family.

Results

The bMERB domain preferentially binds Rab8 family proteins

Previously reported interactions of different bMERB domain containing proteins with Rab proteins included Rab1, Rab8, Rab10, Rab13, Rab15, Rab35 and Rab36 (Giridharan and Caplan, 2014; Shi et al., 2010), although not all possible combinations of the effectors and the different Rab proteins were tested nor interactions quantified. We therefore set out to systematically confirm and quantify the interaction of 5 of these Rab proteins with the bMERB domains of Mical-1, Mical-3, Mical-cL, EHBP1 and EHBP1L1 via analytical size exclusion chromatography (aSEC) (see Table 1, the aSEC data is shown in Figure 2—figure supplement 1). In these experiments, stable complex formation was detected with Rab8, Rab10, Rab13 and Rab15 (since Rab8, Rab10, Rab13 and Rab15 are closely related in amino acid sequence, we refer to them as the Rab8 family [Klöpper et al., 2012]). Rab1, however, failed to form stable complexes with bMERB-domain proteins, indicating low affinity.

Systematic analysis of interactions between Rab proteins and the bMERB domains of different proteins. Binding was systematically tested by analytical size exclusion chromatography (+ indicates binding in these experiments, − indicates that no complex formation was observed) and affinities were determined by ITC.

| Mical-1 | Mical-3 | Mical-cL | EHBP1 | EHBP1L1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rab1 KD | + 2.2 µM | + 2.6 µM | + 5.2 µM | − > 10 µM | − > 10 µM |

| Rab35 KD | n.d. | n.d | + 1.8 µM | n.d | n.d |

| Rab8 KD,1 KD,2 | + 55.5 nM 480 nM | + 27.9 nM 4.4 µM | + 253 nM | + 397 nM | + 159 nM 159 nM |

| Rab10 KD | + n.d. | + n.d. | + 790 nM | + n.d. | + n.d. |

| Rab13 KD | + n.d. | + n.d. | + 94 nM | + n.d. | + n.d. |

| Rab15 KD | + n.d. | + n.d. | + 33 nM | + n.d. | + n.d. |

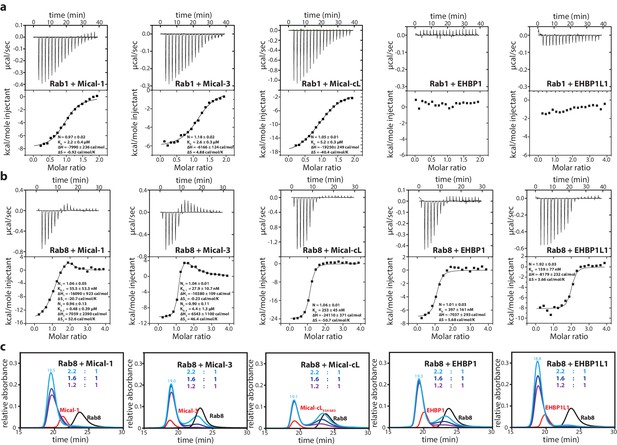

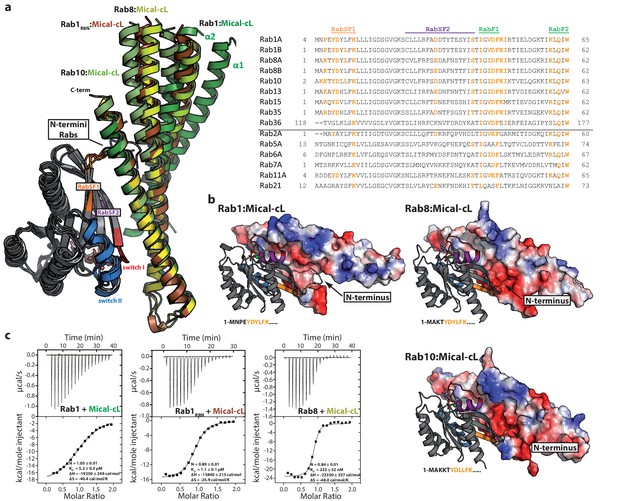

In order to quantitatively verify the preference of the bMERB domain for Rab8 family members rather than Rab1 we performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements comparing the interaction of Rab1 and Rab8 with the different bMERB domains. Whereas we observed KD values of 2.2–5.2 µM for Rab1 binding to the bMERB domains of Mical proteins and no detectable binding of Rab1 to the bMERB domains of EHBPs (Table 1 and Figure 2a), we detected strong binding and ca. 100 nanomolar affinities for Rab8 and the different bMERB domains (see Table 1 and Figure 2b). Using Mical-cL as one representative of the bMERB family, we saw that all members of the Rab8 family bound Mical-cL with high nanomolar affinities, compared to Rab1 (KD = 5.2 µM) and Rab35 (KD = 1.8 µM; Table 1 and Figure 2—figure supplement 2). The highest affinity observed was that of Rab15 and Mical-cL with a KD of 33 nM. In accordance with the strong specificity of EHBPs towards the Rab8 family, Rab1a, Rab1b and Rab35 (a close relative of Rab1 which is also sometimes referred to as Rab1c) were previously shown not to interact with EHBP1/EHBP1L1 (Shi et al., 2010; Nakajo et al., 2016).

The bMERB domains preferentially interact with Rab8-family members.

(a) Whereas Rab1 binds to Mical-1, Mical-3 and Mical-cL with low affinity and does not show detectable binding to EHBPs, (b) Rab8 binds with high affinity to all effector domains tested. Additionally, we observed two separate binding sites in the ITC experiments for Rab8 and Mical-1, Mical-3 and EHBP1L1 (the results of the binding fit including the stoichiometry, the KD, the binding enthalpy and the binding entropy are shown within the ITC spectra). (c) Mixing different ratios of Rab8 and the RBDs (1.2:1, 1.6:1 and 2.2:1), the 2:1 stoichiometry of binding was confirmed by aSEC for Rab8:Mical-1 and Rab8:EHBP1L1, whereas a 1:1 stoichiometry was observed for Rab8:Mical-3, Rab8:Mical-cL and Rab8:EHBP1L1 as indicated by a second peak corresponding to free excess Rab8. Note that the second low affinity binding site present in Mical-3 observed via ITC could not be detected via gel filtration.

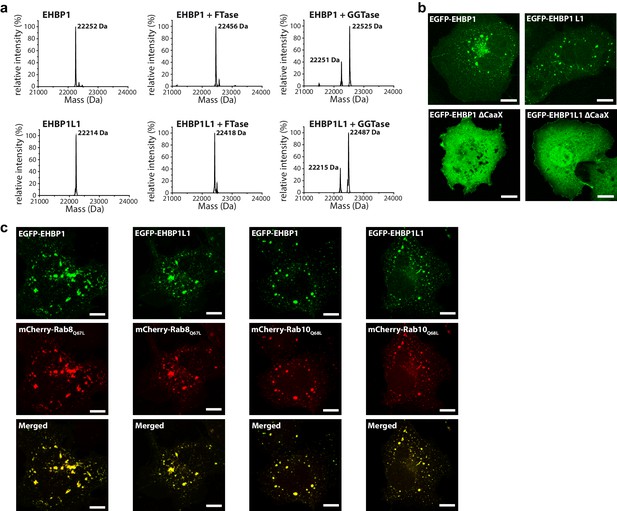

EHBPs colocalize with Rab8-family members

Interestingly, in addition to the RBDs, EHBPs also contain CaaX-boxes at their C-termini (EHBP1: CVLQ; EHBP1L1: CVLS; Figure 1) for posttranslational modification with prenyl-groups. Therefore, we set out to test whether these motifs can be prenylated in vitro and if prenylation is responsible and necessary for correct intracellular localization. In vitro, both proteins can be farnesylated and geranylgeranylated by FTase and GGTase I, respectively. However, in accordance with the C-terminal amino acids of the CaaX-boxes being glutamine or serine (Zhang and Casey, 1996), we observed preferential farnesylation (Figure 3a). Using constructs containing the RBD with or without the CaaX-boxes, we next looked at the intracellular localization. These experiments clearly showed a CaaX-box dependent localization of both proteins to intracellular structures resembling endosomes (Figure 3b), as previously reported for the full length proteins (Shi et al., 2010). Additionally, both proteins showed strong colocalization with constitutively active Rab8 and Rab10 (i.e. Rab8Q67L and Rab10Q68L), both known to act at endosomes (Figure 3c), further supporting the function of this family of effector proteins as Rab8-family binding partners.

Prenylated EHBP1 and EHBP1L1 colocalize with Rab8 and Rab10.

(a) EHBP1 and EHBP1L1 can be prenylated in vitro as shown by mass spectrometry. After incubation of the purified proteins including the CaaX-motifs (theoretical masses of the purified proteins: 22253.3 Da (EHBP1); 22214.0 Da (EHBP1L1); left panel) with Farnesytransferase (FTase, middle panel) or Geranylgeranyltransferase (GGTase, right panel) farnesylation/geranylgeranylation lead to an increase in mass of 205.4/272.5 Da, respectively. Note that farnesylation, in contrast to geranylgeranylation, appears to be more efficient under similar conditions and goes to completion. This is in agreement with the sequence of the CaaX-motifs in both proteins containing a Gln/Ser at their C-terminus which has been shown to favor farnesylation. (b) Whereas the constructs containing the bMERB domain and the CaaX-motif (EHBP11047-1231, EHBP1L11340-1523) localize to intracellular structures resembling endosomes, deletion of the CaaX-motif (∆CaaX) leads to a cytosolic distribution for both EHBP1 and EHBP1L1 (Scale bars: 10 µm). (c) Both EGFP-EHBP11047-1231 and EGFP-EHBP1L11340-1523 (upper panel) show strong colocalisation with mCherry-Rab8Q67L and mCherry-Rab10Q68L (middle panel) as indicated in the merged images (lower panel). The localization pattern resembles that of endosomes (Scale bars: 10 µm).

Some bMERB domains can bind two Rab proteins simultaneously

Besides the specificity of bMERB domains towards the Rab8 family, another interesting observation was made in the ITC experiments comparing the stoichiometry of binding of Rab8 and the different RBDs: Whereas Rab8 bound in a 1:1 stoichiometry to Mical-cL and EHBP1, a 2:1 stoichiometry binding was observed for Mical-1, Mical-3 and EHBP1L1 (Table 1 and Figure 2b). For Rab8 and Mical-1/Mical-3, the ITC experiments show one high-affinity enthalpy-driven and one lower affinity entropy-driven binding site, compared to two binding sites with similar affinity for Rab8 and EHBP1L1.

In order to confirm the observed differences, we repeated the aSEC experiments with varying ratios of Rab8 and the different RBDs of Micals and EHBPs (1.2:1, 1.6:1 and 2.2:1; Figure 2c). These experiments clearly confirmed the aforementioned differences in the stoichiometry of binding with a 2:1 stoichiometry being observed for the Rab8:EHBP1L1 and Rab8:Mical-1 complexes, but not for others tested. The low affinity second binding site of Mical-3 (KD = 4.4 µM as determined by ITC, Table 1) could also not be detected in these experiments, suggesting dynamic complex formation with a large koff. These data show that Mical-1 and EHBP1L1 contain two binding sites that bind Rab8 with high affinity, whereas Mical-3 (and possibly Mical-cL and EHBP1) contain one high affinity and a second lower affinity binding site for Rab8.

The presence of two distinct Rab binding sites on certain bMERB domains was a striking observation pointing towards a possible function of these effector proteins in sorting cargo and/or linking different endosomal trafficking pathways regulated by different Rab proteins. In accordance with this idea, recent studies on Mical-L2 dependent GLUT4 translocation showed that trafficking was dependent on a concerted action of Rab8 and Rab13 (Sun et al., 2010, 2016). We consequently also tested whether the effector proteins might be able to simultaneously bind two different Rab proteins in a 1:1:1 (RabX:effector:RabY) complex using both Rab8 and Rab13 and the corresponding aSEC experiments clearly confirmed the formation of a ternary complex of Rab8:Mical-1:Rab13 as well as Rab8:EHBP1L1:Rab13 (Figure 2—figure supplement 3).

The structural basis of Rab:bMERB interaction

In order to understand the mode of interaction of Rab proteins and the C-terminal Rab-binding domain of Micals/EHBPs, we first aimed at determining the structure of the RBD of one member of these families. We succeeded in crystallizing a selenomethionine derivative of Mical-31841-1990 containing the whole predicted bMERB domain and solved the structure with a resolution of 2.7 Å (data and refinement statistics are shown in Table 2).

Data-collection and processing statistics (values in parentheses are for the outer shell).

| SeMet Mical-31841-19902† | Rab1:Mical-cL534-683 | Rab8:Mical-cL534-683 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection* | |||

| X-Ray Source | X10SA at SLS | X10SA at SLS | X10SA at SLS |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.978956 | 0.99992 | 1.00009 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 47.8–2.7 (2.8–2.7) | 45.8–2.3 (2.4–2.3) | 46.0–2.85 (2.95–2.85) |

| Space group | P 21 21 21 | I 2 2 2 | C 2 2 21 |

| Unit cell a, b, c (Å) α, β, γ (°) | 51.9, 78.8, 95.6 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 61.75, 129.38, 129.85 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 62.4, 122.4, 139.15 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| No. of reflections Total Unique | 272679 (28873) 20544 (2119) | 308332 (36902) 23530 (2760) | 162311 (16579) 12810 (1224) |

| Multiplicity | 13.3 | 13.1 | 12.7 |

| Completeness | 99.1 (98.5) | 100.00 (100.00) | 99.9 (100.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 13.8 (114.6) | 10.5 (74.3) | 8.9 (77.6) |

| Rmeas (%) | 14.4 (119.1) | 10.9 (77.2) | 9.2 (80.6) |

| I/σ(I) | 16.8 (3.6) | 16.27 (3.89) | 16.45 (3.19) |

| f’ / f’’ | -7.29 / 3.84 | - | - |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 47.8–2.7 (2.77–2.7) | 45.8–2.3 (2.4–2.3) | 46.0–2.85 (3.07–2.85) |

| No. of reflections (work set) | 10553 | 23521 | 12808 |

| Rwork (%) | 25.1 (20.5) | 17.9 (26.9) | 23.7 (31.1) |

| Rfree (%) | 28.2 (36.2) | 20.7 (29.8) | 28.8 (35.0) |

| No. of atoms Protein Ligands Water | 2095 14 - | 2552 33 27 | 2426 33 2 |

| B-factors Protein Ligands Water | 72.9 65.2 - | 76.7 49.8 73.1 | 101.2 111.2 122.6 |

| R.m.s deviations Bond length (Å) Bond angles (°) | 0.016 1.809 | 0.008 1.104 | 0.009 1.175 |

| Ramachandran plot Favored Additionally allowed Outliers | 98.8 1.2 0 | 98.4 1.6 0 | 96.1 3.3 0.7 |

| PDB entry code | 5SZG | 5SZH | 5SZI |

| Rab10:Mical-cL534-683 | Rab101-175:Mical-1918-1067 | Rab1R8N:Mical-cL534-683 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| X-Ray Source | X10SA at SLS | X10SA at SLS | X10SA at SLS |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.00009 | 0.99997 | 0.91908 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 48.2–2.66 (2.7–2.66) | 44.0–2.8 (2.9–2.8) | 44.8–2.8 (2.85–2.8) |

| Space group | P 21 21 2 | P 21 21 21 | C 2 2 21 |

| Unit cell a, b, c (Å) α, β, γ (°) | 153.7, 61.9, 55.6 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 58.4, 59.0, 198.2 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 62.2, 117.0, 139.4 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| No. of reflections Total Unique | 187267 (6488) 15861 (676) | 222905 (21259) 17508 (1689) | 170436 (8892) 12904 (645) |

| Multiplicity | 11.8 | 12.7 | 19.2 |

| Completeness | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.6 (99.9) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 13.7 (158.6) | 11.8 (72.3) | 7.6 (110.6) |

| Rmeas (%) | 14.3 (167.8) | 12.3 (75.4) | 7.9 (114.9) |

| I/σ(I) | 12.2 (1.4) | 14.1 (3.3) | 22.8 (2.45) |

| f’ / f’’ | - | - | - |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 48.2–2.66 (2.83–2.66) | 44.0–2.8 (2.98–2.80) | 44.8–2.8 (3.0–2.80) |

| No. of reflections (work set) | 15857 | 17499 | 12904 |

| Rwork (%) | 22.4 (30.2) | 23.7 (29.4) | 20.8 (30.8) |

| Rfree (%) | 26.6 (36.9) | 28.8 (35.6) | 26.1 (38.4) |

| No. of atoms Protein Ligands Water | 2559 40 39 | 3676 66 4 | 2565 33 3 |

| B-factors Protein Ligands Water | 77.8 77.9 70.2 | 88.6 85.4 68.7 | 86.2 81.2 73.8 |

| R.m.s deviations Bond length (Å) Bond angles (°) | 0.004 0.756 | 0.013 1.506 | 0.010 1.178 |

| Ramachandran plot Favored Additionally allowed Outliers | 98.1 1.9 0 | 96.7 3.3 0 | 98.1 1.6 0.3 |

| PDB entry code | 5SZJ | 5LPN | 5SZK |

-

*All data sets were collected from one single crystal on beamline X10SA of the Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland)

-

†Data collections statistics for SAD data refer to unmerged Friedel pairs.

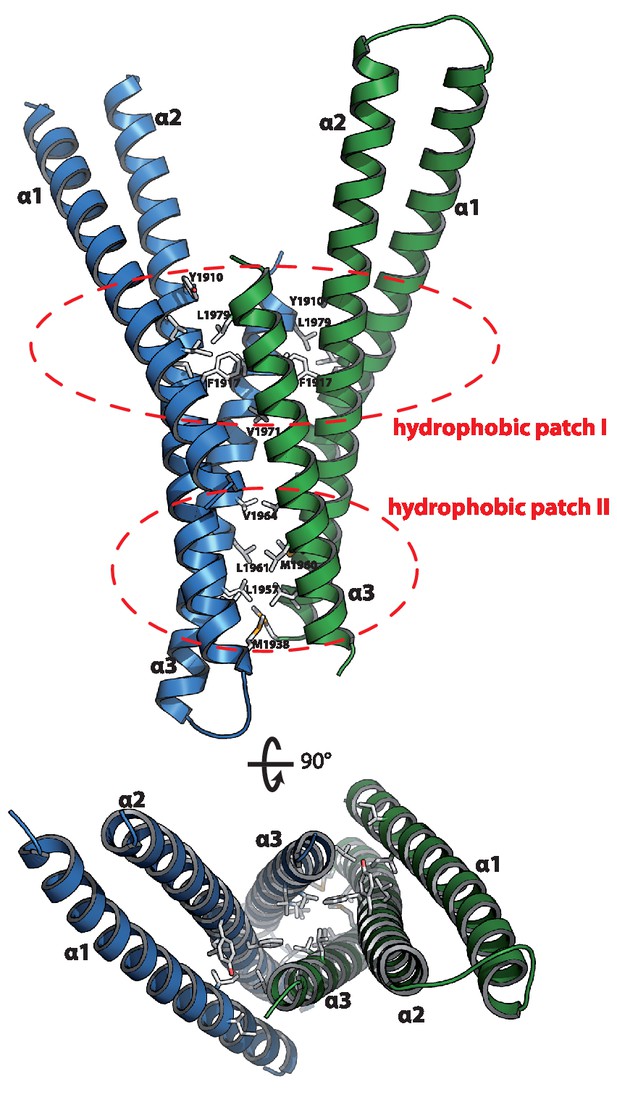

The asymmetric unit contains two copies of Mical-3 that form a central 4-stranded coiled-coil composed of α-helices 2 and 3 of each monomer flanked by α-helices 1 on both sides (Figure 4a). Interactions between the monomers mainly occur via two hydrophobic patches and some additional charged interactions (Figure 2b). Overall, the structure shows that each monomer consists of a central helix (α2, residues K1891-R1937) and N- and C-terminal helices folding back on this central helix.

Structure of the Rab binding domain of Mical-3.

Mical-3 folds into three α-helices, the central α-helix 2 and α-helices 1 and 3 folding back on the central helix. The dimer observed in the asymmetric unit is formed mostly by hydrophobic interactions involving the same hydrophobic patches in both monomers, and α-helices 2 and 3 from each monomer form a central 4-stranded coiled-coil.

The completely α-helical fold of this protein is common to many Rab effector proteins and most of them bind the interacting Rab proteins via two α-helices (Mott and Owen, 2015). In order to test whether this is also true for the bMERB domains, we screened for crystallization conditions of bMERB:Rab complexes. Well diffracting crystals were found using the RBD of Mical-cL (residues 534–683) in complex with different Rab proteins (Rab1, Rab8 and Rab10). All structures were solved using a single chain of Mical-3 and the structure of Rab1 (pdb id 3nkv) or Rab8 (pdb id 4lhw) as search models for molecular replacement (the data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 2).

In all structures (Rab1:Mical-cL, Rab8:Mical-cL and Rab10:Mical-cL) we found one Rab protein bound to one molecule of Mical-cL (Figure 5a), in agreement with the previous observations that all Rab proteins tested bind only one site in Mical-cL. Most interactions were visible between the Rab proteins and α-helix 3 of Mical-cL with some additional contributing residues from α-helix 2, forming extensive contacts involving residues within switch I and II of the Rab proteins (Figure 5b). In all cases, hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic patch II in Mical-cL and residues from Rabs forming a hydrophobic pocket (residues Ile43, Phe70 and Ile73 in Rab8) and a triad of aromatic amino acids (Phe45, Trp62, Tyr77 in Rab8) known from all Rab:effector complexes solved to date (Itzen and Goody, 2011) were also observed in the Rab:Mical-cL structures.

The specificity of Rab proteins binding to bMERB domains.

(a) A superposition of the complex structures of Rab1:Mical-cL, Rab8:Mical-cL, Rab10:Mical-cL and Rab1R8N:Mical-cL shows that Rabs bind Micals via their N-terminus (including RabSF1), RabSF2 as well as the switch regions (Rabs are shown in cartoon representation, switch I – red, switch II – blue, RabSF1 – orange, RabSF2, magenta; Micals are shown in cartoon representation and colored in dark green (Mical-cL interacting with Rab1), yellow (Mical-cL interacting with Rab8), light green (Mical-cL interacting with Rab10) or brown (Mical-cL interacting with Rab1R8N). The sequence alignments of different Rab proteins clearly shows that the interacting residues of Rab proteins with Micals (red residues) are highly conserved (orange residues) in Rab1 and Rab8 family members (Rab1a, Rab1b, Rab35, Rab8, Rab10, Rab13, Rab15), but not in other Rabs (below the black line). (b) In all structures of Rab proteins in complex with Mical-cL, the N-termini of the Rab proteins point towards a negatively charged patch of Mical-cL (Rabs are shown in cartoon representation as above; the surface of Mical-cL is colored by charge, red – negative charge, blue – positive charge). The sequence of the N-terminal residues of each Rab protein is shown below the corresponding structure: Whereas Rab1 contains a negatively charged glutamate at position 4, Rab8 and Rab10 contain one or two lysine residues at position 3 or at position 3 and 4, respectively. Consistently, the negatively charged N-terminus of Rab1 seems to repel α-helices 1 and 2 of Mical-cL and they adopt a conformation slightly further away from Rab1 compared to Rab8 and Rab10 (also see (a)). However, after mutating the 4 N-terminal residues of Rab1 to the corresponding sequence of Rab8 (the resulting chimera is called Rab1R8N), the structure of Rab1R8N:Mical-cL shows a similar conformation of α-helices 1 and 2 as in the structure of Rab8:Mical-cL. (c) Consistently, ITC measurements show that the affinity of binding increases approximately five-fold after mutating the N-terminal residues (Rab1:Mical-cL: KD = 5.2 µM; Rab1R8N:Mical-cL: KD = 1.1 µM; Rab8:Mical-cL: KD = 0.23 µM).

Interestingly, the Rab-binding interface in Mical-cL has a substantial overlap with the dimer interface observed in the structure of Mical-3 above. Additionally, even though all Mical constructs used have a similar molecular weight of ~18 kDa, whereas Mical-1 runs as an apparent monomer in aSEC and binding of a Rab protein induces a clear shift to higher molecular weight, both Mical-3 and Mical-cL run as apparent dimers in aSEC and binding of a Rab protein disrupts the dimer, thus not leading to a shift in retention time upon complex formation (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). It is however not clear at this point whether the dimer formation of Mical-3 and Mical-cL and the disruption of the dimer upon Rab-binding is of functional significance.

The specificity of effector proteins towards certain Rab families is generally achieved via interaction with regions termed Rab subfamily motifs (RabSFs) 1–4 (Khan and Ménétrey, 2013; Moore et al., 1995; Pereira-Leal and Seabra, 2000). In the Rab:Mical-cL structures, we observed extensive interaction of Mical-cL with RabSF1 (Tyr6, Asp7, Leu9, Lys11 in Rab10) and (less interactions) with RabSF2 (Asp31, Ser40 in Rab10). Accordingly, the sequence alignment of different Rab proteins (Figure 5) shows strong conservation of the interacting amino acids within these motifs amongst Rab1 (Rab1a/b, Rab35) and Rab8 (Rab8a/b, Rab10, Rab13, Rab15) family members that interact with bMERB domains, but not for other Rab proteins (a comparative scheme of the residues involved in interactions in the different complexes is shown in Figure 5—figure supplement 1a). Since the interacting residues in the RabSF1 and RabSF2 regions are strongly conserved between both Rab1 and Rab8 families, this did not explain the observed preference of the RBD towards the Rab8 family. However, we observed that the main chain atoms of the N-terminal residues preceding the RabSF1 motif can be traced in the electron density and seem to interact with amino acids within α-helix 1 and 2 of Mical-cL, even though the electron density in this region did not allow a precise localization of the side chains. In contrast to the main interacting helix α3, which adopts a similar position in all three structures, we observed slightly different orientations of the α-helices 1 and 2, adopting a position slightly further away from Rab1 compared to Rab8 and Rab10 (Figure 5a). Interestingly, whereas Rab1 contains a glutamate near the N-terminus (Glu4), all Rab8 family members contain one or (in the case of Rab10) two lysine residues in this region that point towards a negatively charged patch in Mical-cL (Figure 5b). Additionally, Rab35 contains an Arg residue within this N-terminal region and also displays a slightly higher affinity towards Mical-cL compared to Rab1 (Figure 2—figure supplement 2). We therefore tested whether these N-terminal residues of the Rab proteins might determine the specificity of bMERB domains towards Rab8 and its homologues rather than Rab1. We constructed a chimera of Rab1 containing the 4 N-terminal aa of Rab8, thus exchanging the negatively charged glutamate for a positively charged lysine. The x-ray crystallographic structure of this Rab1 chimera (termed Rab1R8N) in complex with Mical-cL clearly showed that the helices 1 and 2 move closer and adopt a similar conformation as observed in the structures of Rab8:Mical-cL and Rab10:Mical-cL (Figure 5a). Additionally, ITC measurements showed that the chimera had an approximately five-fold increased binding affinity compared to Rab1 (Figure 5c). In contrast to Rab1, the chimera Rab1R8N bound both EHBP1 and EHBP1L1 in aSEC experiments (Figure 5—figure supplement 1b), thus clearly indicating that the N-terminus is important for the interaction and contributes to the observed specificity of bMERB domains towards Rab proteins.

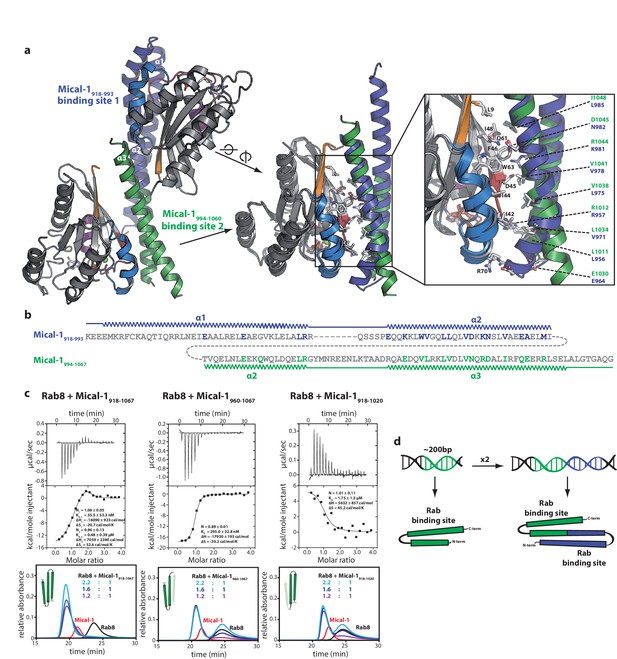

The second Rab binding site has evolved by gene duplication

Stimulated by the evidence for two Rab binding sites in some bMERB domains (Mical-1, Mical-3 and EHBP1L1), we searched for crystallization conditions of these RBDs with Rabs in a 1:2 stoichiometry. Crystallization conditions were found using a complex of Rab101–175 and the RBD of Mical-1 (residues 918–1067), yielding crystals that diffracted to a resolution of 2.8 Angstrom at a synchrotron X-ray source and the resulting structure indeed showed two molecules of Rab10 bound to Mical-1 (Figure 6a). In addition to the binding site corresponding to the one previously observed in Mical-cL, an additional binding site was identified: Whereas this site is composed of the N-terminal half of the bMERB domain (α-helix 1 and the first half of α-helix 2), the Rab binding site observed in both Mical-1 and Mical-cL comprises the C-terminal half (second half of α-helix 2 and α-helix 3).

The two Rab binding sites are highly similar.

(a) The structure of Mical-1 in complex with Rab10 shows two molecules of Rab10 bound to Mical-1 at different sites. Whereas one Rab protein binds to α-helix 1 and the first half of α-helix 2 (Mical-1918-991, binding site 1, blue), the second molecule of Rab10 binds the second half of α-helix 2 and α-helix 3 (Mical-1994-1060, binding site 2, green). Upon superimposition of both binding sites, the strong similarity becomes obvious and the helices from both binding sites adopt very similar positions. Furthermore, the interactions are highly similar in both cases as can be seen in the close-up view on the right (similar Rab-interacting residues within binding site 1 and 2 are shown in blue and green, respectively). (b) The strong conservation of interacting residues within both halves of the Mical-1 bMERB domain can also be seen in the sequence alignment of the N- and C-terminal halves. Additionally, the alignment shows that α-helix 1 and the first half of α-helix 2 (binding site 1) correspond to the second half of α-helix 2 and α-helix 3 (binding site 2), respectively (the secondary structure is indicated above and below the corresponding sequences, interacting and conserved residues within binding site 1 and 2 are highlighted in blue and green). (c) Whereas the whole bMERB domain of Mical-1 can bind two Rab molecules (left), deletion of either α-helix 1 (middle) or α-helix 3 (right) impairs binding to binding site 1 or 2, respectively. This effect could be shown both by aSEC and ITC (note the enthalpy-driven high-affinity binding site 2 and the entropy-driven lower-affinity binding site 1 that can be clearly distinguished, a schematic drawing of the different constructs is shown within the aSEC graphs). (d) Based on the observations made above, we propose that both binding sites must have evolved from a common ancestor by gene duplication of a 200 bp DNA fragment coding for the original gene product, a single α-hairpin. The fusion lead to the arrangement of the α-helices observed in bMERB domains, with the central α-helix 2 as a continuous connecting helix of both repeats, similar to the architecture of spectrin repeats.

Upon closer inspection and alignment, a strong similarity between the two Rab binding sites in Mical-1 became obvious, involving the same/similar residues both within the two different molecules of Rab10 as well as the two binding sites in Mical-1, respectively (Figure 6a). An alignment of the sequences of the corresponding N- and C-terminal halves of all different Micals (Mical-1, Mical-cL, Mical-3, Mical-L1 and Mical-L2), EHBP1 and EHBP1L1 (see Figure 6—figure supplement 1, the example for Mical-1 is shown in Figure 6b) with Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011) highlights the striking similarity between the binding sites and shows the strong conservation of Rab-interacting residues within the two binding sites. A non-exhaustive list and a close-up view of several of these interactions is shown in Table 3 and Figure 6—figure supplement 2, respectively. It should be noted that use of the N- and C-terminal halves of only one of the bMERB domains was not sufficient for Clustal Omega alignment to converge and find the conserved residues within the separate halves. In contrast, the webserver HHrepID (Biegert and Söding, 2008) nicely predicted and aligned the two repeats present in Mical-1 with a p-value of 1.1–5.

Non-exhaustive list of conserved interactions between Rab10 and the separate binding sites in Mical-1.

| Mical-1 | Rab10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Binding site 1 | Binding site 2 | |

| Glu964 | Glu1030 | Arg70 |

| Lys981 | Arg1044 | Asp45 |

| Asn982 | Asp1045 | Gln61 |

| Leu956 | Leu1011 | Ile42 |

| Val971 | Leu1034 | Ile42 |

| Leu975 | Val1038 | Ile44, Ile74 |

| Val978 | Val1041 | Ile44, Phe46, Trp63 |

| Val985 | Ile1048 | Leu9, Phe46, Ile48 |

Consistent with the localization of the two separate binding sites within the N-terminal and the C-terminal half of the bMERB domain, respectively, deletion constructs lacking either α-helix 1 (Mical960–1067) or α-helix 3 (Mical-1918–1020) displayed a clear 1:1 stoichiometry of Rab binding both in aSEC and ITC experiments (Figure 6c). Furthermore, the ITC data allowed us to clearly allocate the high affinity binding to the C-terminal binding site and the lower affinity binding to the N-terminal binding site.

In summary, the strong conservation of interacting residues between both sites as well as the structural conservation of the binding sites lead us to conclude that this family of Rab binding proteins must have evolved via gene duplication (Figure 6d). Furthermore the strong conservation of interacting residues not only between the two separate binding sites in Mical-1, but also between the different bMERB domains (see alignments in Figure 6—figure supplements 1 and 3) suggests that all of these proteins contain a second (possibly low affinity) binding site. Further analysis of the Rab specificity of both sites within these proteins will therefore be of great interest.

Discussion

In this publication, we present a thorough biochemical and structural analysis of a Rab effector domain termed bivalent Mical/EHBP Rab binding (bMERB) domain. The results show that the domains probably constitute a Rab8-effector family involved in endosomal trafficking, and the Rab-binding specificity can be well explained from the 3-dimensional structures of complexes determined in this work. Furthermore, we show that at least some of these domains contain two separate binding sites for Rab-proteins, suggesting previously unknown functions, as discussed below. The strong similarity between the 2 binding sites within one effector domain strongly suggests an evolutionary development via gene duplication.

The high specificity of the effector domains towards Rab8 family members can be well explained from the structural analysis of Rab:bMERB complexes. Specificity-determining interactions were seen between the effector domains and the RabSF1 and RabSF2 motifs. However, additional interactions were required to increase the specificity even further, thus allowing the proteins to distinguish Rab1- and Rab8-family members. In this regard, we showed that the N-terminal residues preceding the RabSF1 motif contribute to this specificity, an observation that has previously not been made in other Rab:effector interactions. However, as alluded to in the introduction, the presence of multiple isoforms (e.g. Mical-1, Mical-L1 etc.) of the proteins, as well as the demonstrated presence of two separate binding sites, might also point towards a broader and more diverse Rab-binding spectrum and is the subject of ongoing research in our work.

The 3-dimensional structures of the effector domains solved in this work showed a solely α-helical fold common to many other Rab effector proteins (Oesterlin et al., 2014). Further comparison with other known Rab:effector structures showed that the main interacting helix in Rab:bMERB complexes (e.g. α-helix 3 in Mical-cL) adopts a similar position to that of the main interacting helix in the structures of Rab27:Slp2-a (Chavas et al., 2008), Rab27:Slac2a/melanophilin (Kukimoto-Niino et al., 2008) and Rab3:Rabphilin-3a (Ostermeier and Brunger, 1999) (see Figure 5—figure supplement 2 for a comparison). Interestingly, in all three examples, the Arg/Lys contacting Asp45 in our Mical:Rab structures is also conserved in these effector proteins, and the Asp/Asn following this basic residue and contacting Gln61 in Rabs is conserved in both Slp2-a and Slac2a. Intriguingly, these effector domains also display similar binding affinities as bMERB domains towards their cognate Rabs (KD = 13.4 nM for Rab27:Slp2-a, KD = 112 nM for Rab27:Slac2-a/melanophilin) (Fukuda, 2006), and these are amongst the highest affinities observed for Rab:effector interactions.

Both the biochemical as well as the structural analysis identified a second binding site in Mical-1, Mical-3 and EHBP1L1, thus allowing these effectors to bind Rab proteins in a 1:2 stoichiometry. In contrast to the bMERB domain proteins, Rab:effector complexes that were previously characterized display either a 1:1 or 2:2 stoichiometry, where the 2:2 complexes are usually formed by a central effector dimer with symmetrical binding interfaces on both sites (Oesterlin et al., 2014). On the other hand, multivalent Rab effector proteins have been described previously (examples are Rab4 and Rab5 binding to Rabaptin-5 (Vitale et al., 1998), Rab6 and Rab11 binding to Rab6IP1 (Miserey-Lenkei et al., 2007) or the extreme case of Gcc185 with five sites binding to Rab1a/b, Rab2a/b, Rab6a/b, Rab9a/b, Rab15, Rab27, Rab30, Rab33, Rab35 and Rab36 (Hayes et al., 2009). However, all of these effectors contain separate Rab-binding domains, each in turn only binding one Rab protein. The work presented constitutes the first description of two Rab proteins binding a single effector domain.

The separate binding sites within one domain not only represent a novel finding for Rab effector molecules, but also suggest intriguing and hitherto unknown functions of these proteins. Such functions could include linking Rab-decorated vesicles to a target membrane or other vesicles via a central bivalent effector. On the other hand, concerted Rab cascades and feedback loops have been observed with effector domains fused to GEFs or GAPs of one Rab acting upstream or downstream of a second Rab, helping to recruit or remove Rab proteins from a certain membrane (Pfeffer, 2013). Bivalent effectors could act in a similar manner in a positive feedback loop, initially being recruited by activated Rab proteins and subsequently helping in the recruitment and stabilization of further Rabs at this site to establish Rab membrane microdomains (Pfeffer, 2013). In fact, the presence of one high affinity and one low affinity Rab binding site as observed in some bMERB effectors could further enhance the formation of Rab microdomains: Whereas the Rab bound to the high affinity site would essentially stay bound within physiologically relevant timescales, the additional Rab protein recruited by the low affinity site could dissociate again and recruit another effector molecule via the high affinity site, thus helping to concentrate Rabs within small areas on the membrane.

Additionally and similar to the suggested function of Rab6IP linking Rab6 and Rab11 mediated vesicular trafficking events (Miserey-Lenkei et al., 2007), bMERB domain containing effectors might fulfill analogous functions in vesicular trafficking and act as effector Rab hubs. The possible importance of such concerted membrane recruitment cascades of Rabs and other proteins involved in membrane trafficking has been previously highlighted for Mical-L1 connecting Rab35 and Rab8, and this was aptly referred to as a membrane hub (Rahajeng et al., 2012; Giridharan et al., 2012). Furthermore, recent studies on Mical-L2 dependent GLUT4 translocation showed that trafficking was dependent on a concerted action of Rab8 and Rab13 (Sun et al., 2010, 2016). In another study it was shown that Mical-L1 is recruited to recycling endosomes by Rab35 and subsequently recruits other Rab proteins (Rab8, Rab13 and Rab36) (Kobayashi et al., 2014). In this work, the authors concluded that dimerization of Mical-L1 allows a concerted recruitment and binding of two separate Rabs to an effector dimer. However, our data now show how the 2 separate binding sites presumably also present in Mical-L1 and Mical-L2 (see Figure 6—figure supplement 1) could help in establishing this concerted action of two Rabs by connecting them via one bivalent effector protein in an (intermediate) 1:1:1 complex, thus explaining for the first time the structural and biochemical basis of the Rab hub function. The strong sequence homology of different bMERB domains including both binding sites and the fact that all Rab8 family proteins reported to interact with Micals/EHBPs are implicated in different steps of endocytic trafficking (Wandinger-Ness and Zerial, 2014) as well as previously published data thus points towards an important function of Micals/EHBPs in sorting of endocytic cargo with different destinations in the cell.

Another possible functional implication of the separate binding sites follows from the observation of an auto-inhibited state within Micals. Previous studies have shown that the bMERB domains in Micals can bind to their CH/LIM domains, forming an auto-inhibited intramolecular interaction that can be released by competitive binding of Rab proteins, thus allowing for the interaction with actin only after binding of Rabs (Sun et al., 2016; Sakane et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2008). The structural basis as well as the functional significance of this competitive binding will be an interesting topic for future research, especially regarding the binding region at the RBD responsible for auto-inhibition. The two binding sites might therefore also have separate functions, serving as a membrane recruitment site by Rabs via one site (presumably the high-affinity binding site) and release of the auto-inhibition due to competitive binding of the CH/LIM domains and Rabs at the second binding site.

In the last part of the study, we have shown that the two binding sites share a strong similarity and bind Rab proteins via similar residues within the interaction surfaces, thus indicating that the RBD have evolved via duplication of a common ancestor supersecondary structure element (Figure 6d) (Söding and Lupas, 2003). The underlying single α-hairpin motifs making up the separate Rab-binding sites are known from other Rab-effectors such as Rabenosyn-5 (Khan and Ménétrey, 2013; Eathiraj et al., 2005), and the resulting fused α-hairpins observed in Micals and EHBPs strongly resemble the architecture of spectrin repeats, each being connected via one continuous helix (Han et al., 2007; Pascual et al., 1997). Because of the strong similarity between the repeats of the different isoforms of Micals and EHBPs, but less similarity between both repeats within the bMERB domains (Figure 6—figure supplement 1b), we suggest that the duplication must have occurred early in evolution in one common ancestor bMERB domain. The two repeats have since diverged in terms of overall sequence, but the ability to bind Rab proteins has remained in at least some cases, as shown in this study. Exploration of the binding specificity of both binding sites of the bMERB proteins towards Rabs (and possibly other GTPases [Rahajeng et al., 2012]) will therefore be of great interest.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

Request a detailed protocolRab proteins were expressed and purified as described previously (Rab1 [Schoebel et al., 2009] and other Rab proteins [Bleimling et al., 2009]) and preparatively loaded with GppNHp (Guanosine-5’-[β-γ-Imido]-triphosphat) for interaction studies with their effector proteins. For this purpose, the proteins were incubated in the presence of 5 mM EDTA, 5–10% glycerol, three-fold molar excess of GppNHp over the Rab protein and 0.5 units alkaline phosphatase per mg Rab protein for 2 hr at 20°C or at 4°C overnight. Subsequently the proteins were purified via gel filtration in a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTE, 2 mM MgCl2 and 10 µM GppNHp. bMERB domains (amino acid boundaries and Uniprot accession IDs are shown in Figure 6—figure supplement 3) were cloned into a modified pET19 expression vector and proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 DE3 RIL cells (growth at 37°C to OD600 nm = 0.8–1.0, stored at 4°C for 30 min, expression was induced by addition of 0.3–0.5 mM IPTG and cells were grown for 14–18 hr at 20°C). Subsequently the proteins were purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography, cleavage of the His6-tag with TEV-protease and a second Ni2+-affinity purification. Final purification was achieved by gel filtration (Rabs: 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTE, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 µM GDP or GppNHp; Micals: 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 50 or 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTE). In order to express the selenomethionine labeled version of the coiled coil domain of Mical-3, the methionine biosynthesis inhibition method (Van Duyne et al., 1993) was used. The labeled protein was purified as described above. FTase and GGTase I were purified as described previously (Dursina et al., 2006; Kalinin et al., 2001).

For prenylation, EHBP11047-1231/EHBP1L11340-1523, substrate (farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) or geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP); Sigma) and prenyltransferase (FTase or GGTase I) were mixed in a 1:5:0.5 ratio in buffer containing 25 mM Hepes pH 7.2, 40 mM NaCl and 2 mM MgCl2 and incubated for 3 hr at room temperature. To check the extent of prenylation, samples were analyzed by ESI-MS.

Analytical size exclusion chromatography

Request a detailed protocolComplex formation of Rab proteins preparatively loaded with GppNHp and the bMERB effector domains was assessed by analytical size exclusion chromatography (aSEC). The effector domains were used at a concentration of 113 µM, Rab proteins were used at concentrations of 130 µM (Rab:effector stoichiometry of 1.2:1), 180 µM (1.6:1) or 250 µM (2.2:1) and 30 µl of the protein solutions were injected into a Superdex S75 10/300 GL gel filtration column (flow rate 0.5 ml/min, detection of absorption at 280 nm, buffer: 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTE, 2 mM MgCl2).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Request a detailed protocolProtein-protein interaction was studied by ITC using an iTC200 microcalorimeter (MicroCal). Measurements were performed in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM tris (2-carboxymethyl) phosphine (TCEP) at 25°C and for every experiment a technical replicate was performed. 400 µM Rab was titrated into the cell containing 20–40 µM of Mical. Data were analyzed with Origin (Version 7.0, MicroCal).

X-ray crystallography

Request a detailed protocolInitial crystallization conditions for single effector proteins and all protein complexes described here were determined with the JSG Core I-IV, Pact and Protein Complex suites from Qiagen. The sitting-drop vapor diffusion method was used, with a reservoir volume of 70 μl and a drop volume of 0.1 μl protein (15–25 mg ml−1) and 0.1 μl reservoir solution at 20°C. The best conditions were then optimized using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method in order to obtain well diffracting crystals. The seleno-L-methionine labelled Mical-31841–1990 was finally crystallized in 0.1 M Tris pH 7.0 und 45 – 50% PEG 200 (protein concentration 5.5 – 11 mg/ml). Mical-cL534–683 in a 1 to 1 complex ratio with all tested Rab proteins crystallized in similar conditions. The complex with Rab1bFl was crystallized in 0.1 M bis-tris-propane pH 8.4–8.6, 0.2 M tri-sodium citrate and 20–22% (w/v) PEG 3350, with Rab8aFl in 0.1 M bis-tris-propane pH 8.3–8.7, 0.2 M tri-sodium citrate and 18–20% (w/v) PEG 3350 and finally with Rab10Fl in 0.2–0.3 M sodium acetate and 18–22% (w/v) PEG 3,350. The hybrid Rab1bR8N (chimera) in complex with Mical-cL534–683 was crystallized in 0.1 M bis-tris pH 7.5, 0.2 M sodium malonate and 20% (w/v) PEG3350. Mical-1918–1067 crystallized with Rab101-175 in a 1 to 2 ratio under the following conditions: 0.1 M imidazole pH 7.6–8.0 and 6–10% (w/v) PEG 8,000.

Best diffracting crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen and diffraction data were collected on beamline X10SA at the Swiss Light Source (Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland) and processed with XDS (Kabsch, 2010). The structure of Mical-31841–1992 was solved by the single anomalous diffraction method using data collected at the selenium absorption edge. Initial phases and an initial model were obtained with PHENIX AutoSol (Adams et al., 2010). All protein complex structures were solved by the maximum likelihood molecular replacement method using the structures of Mical-31841–1992, Mical-cL534–683, Rab1b (pdb id 3nkv) and Rab8a (pdb id 4lhw) as search models. The initial structure models were completed by hand in Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and refined with phenix.refine (Adams et al., 2010) or Refmac5 (Murshudov et al., 1997) of the CCP4 package (Winn et al., 2011) using the TLS option. Data collection and refinement statistics, as well the Protein Data Bank accession numbers of each presented structure are summarized in Table 1.

Fluorescence microscopy

Request a detailed protocolRab constructs were cloned into pmCherry vector using the XhoI and BamHI restriction sites and to obtain active Rab mutants (Rab8Q67L, Rab10Q68L) quick change mutagenesis was performed. Further EHBP11047-1231, EHBP11047-1227 (missing the CaaX-box), EHBP1L11340-1523 and EHBP1L11340–1519 (missing the CaaX-box) constructs were cloned into pEGFP(C1) vector between EcoRI and SalI sites.

Cos7 cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Cells were grown on a coverslip in 6 well plate until they reached 60–70% confluency and transiently transfected using polyethylenimine (PEI, Polysciences,Inc, 3∶1 PEI:DNA (12∶4 µg). Expression was checked 20–24 hr post transfection. Cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Unreacted paraformaldehyde was quenched with 100 mM glycine in PBS for 15 min. After washing with PBS, cover slips were mounted on glass slides with SlowFade Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Images were taken using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope, 63 × 1.4 NA HC PL APO CS2 oil immersion objective. For Delta CaaX constructs single plane images were taken and for 3D reconstitutions, three dimensional stacks with 0.3-μm steps were acquired. Images from the all focal planes were rendered as a single maximum-intensity projection using Leica software.

Data availability

-

Structure of the bMERB domain of Mical-3Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5SZG).

-

Structure of human N-terminally engineered Rab1b in complex with the bMERB domain of Mical-cLPublicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5SZK).

-

Structure of human Rab10 in complex with the bMERB domain of Mical-1Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5LPN).

-

Structure of human Rab10 in complex with the bMERB domain of Mical-cLPublicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5SZJ).

-

Structure of human Rab1b in complex with the bMERB domain of Mical-cLPublicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5SZH).

-

Structure of human Rab8a in complex with the bMERB domain of Mical-cLPublicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 5SZI).

-

Crystal structure of Rab1b covalently modified with AMP at Y77Publicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 3NKV).

-

Crystal structure of Rab8 in its active GppNHp-bound formPublicly available at the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession no. 4LHW).

References

-

PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solutionActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 66:213–221.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444909052925

-

Chaperone-assisted production of active human Rab8A GTPase in Escherichia coliProtein Expression and Purification 65:190–195.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pep.2008.12.002

-

Identification and specificity profiling of protein prenyltransferase inhibitors using new fluorescent phosphoisoprenoidsJournal of the American Chemical Society 128:2822–2835.https://doi.org/10.1021/ja052196e

-

Features and development of CootActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 66:486–501.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444910007493

-

The MICAL proteins and rab1: a possible link to the cytoskeleton?Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 328:415–423.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.182

-

Distinct Rab27A binding affinities of Slp2-a and Slac2-a/melanophilin: Hierarchy of Rab27A effectorsBiochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 343:666–674.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.001

-

Trafficking cascades mediated by Rab35 and its membrane hub effector, MICAL-L1Communicative & Integrative Biology 5:384–387.https://doi.org/10.4161/cib.20064

-

MICAL-family proteins: Complex regulators of the actin cytoskeletonAntioxidants & Redox Signaling 20:2059–2073.https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5487

-

EHD2 and the novel EH domain binding protein EHBP1 couple endocytosis to the actin cytoskeletonJournal of Biological Chemistry 279:10593–10605.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M307702200

-

The folding and evolution of multidomain proteinsNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 8:319–330.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2144

-

Multiple Rab GTPase binding sites in GCC185 suggest a model for vesicle tethering at the trans-GolgiMolecular Biology of the Cell 20:209–217.https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0740

-

Rab GTPases and microtubule motorsBiochemical Society Transactions 39:1202–1206.https://doi.org/10.1042/BST0391202

-

SelR reverses Mical-mediated oxidation of actin to regulate F-actin dynamicsNature Cell Biology 15:1445–1454.https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2871

-

GTPases involved in vesicular trafficking: structures and mechanismsSeminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 22:48–56.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.10.003

-

Expression of mammalian geranylgeranyltransferase type-II in Escherichia coli and its application for in vitro prenylation of Rab proteinsProtein Expression and Purification 22:84–91.https://doi.org/10.1006/prep.2001.1423

-

The axonal cytoskeleton: from organization to functionFrontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 8:44.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2015.00044

-

Subclass-specific sequence motifs identified in Rab GTPasesTrends in Biochemical Sciences 20:10–12.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-0004(00)88939-2

-

Structures of Ras superfamily effector complexes: What have we learnt in two decades?Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 50:85–133.https://doi.org/10.3109/10409238.2014.999191

-

Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood methodActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 53:240–255.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444996012255

-

EHBP1L1 coordinates Rab8 and Bin1 to regulate apical-directed transport in polarized epithelial cellsThe Journal of Cell Biology 212:297–306.https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201508086

-

BookEffectors of Rab GTPases: Rab binding specificity and their role in Coordination of Rab function and localizationIn: Wittinghofer A, editors. Ras Superfamily Small G Proteins: Biology and Mechanisms 2. Springer International Publishing. pp. 39–66.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07761-1_3

-

Rab GTPase regulation of membrane identityCurrent Opinion in Cell Biology 25:414–419.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2013.04.002

-

Rab13 regulates neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells through its effector protein, JRAB/MICAL-L2Molecular and Cellular Biology 30:1077–1087.https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01067-09

-

EHBP-1 functions with RAB-10 during endocytic recycling in Caenorhabditis elegansMolecular Biology of the Cell 21:2930–2943.https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0149

-

Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle trafficNature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 10:513–525.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2728

-

A complex of Rab13 with MICAL-L2 and α-actinin-4 is essential for insulin-dependent GLUT4 exocytosisMolecular Biology of the Cell 27:75–89.https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E15-05-0319

-

Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycinJournal of Molecular Biology 229:105–124.https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1993.1012

-

Rab proteins and the compartmentalization of the endosomal systemCold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 6:a022616.https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a022616

-

Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developmentsActa Crystallographica Section D Biological Crystallography 67:235–242.https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444910045749

-

Protein prenylation: molecular mechanisms and functional consequencesAnnual Review of Biochemistry 65:241–269.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001325

Article and author information

Author details

Funding

Max-Planck-Gesellschaft

- Amrita Rai

- Roger S Goody

- Emerich Mihai Gazdag

- Matthias P Müller

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB1035, project B05)

- Aymelt Itzen

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB642, project A4)

- Roger S Goody

- Matthias P Müller

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Andrei Lupas (MPI Tübingen) for helpful discussions regarding the evolution of the bMERB domains. Prof. Christian Herrmann (Ruhr-University Bochum) is acknowledged for the generous possibility to measure ITC data using the Auto-iTC200 in his group. Nathalie Bleimling is acknowledged for invaluable technical assistance. We thank the Swiss Light Source (SLS) X10SA beamline staff for the possibility to collect data at the Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland. Many thanks go to Georg Holtermann for his technical support in x-ray crystallography and inhouse data collection. Some expression plasmids used in this work were cloned by the Dortmund Protein Facility (DPF). AI acknowledges support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB1035, project B05) and the authors thank the Max-Planck-Society and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB642, project A4) for financial support.

Copyright

© 2016, Rai et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 3,033

- views

-

- 585

- downloads

-

- 63

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 63

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.18675