Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Reviewer #2:

(1) The use of two m5C reader proteins is likely a reason for the high number of edits introduced by the DRAM-Seq method. Both ALYREF and YBX1 are ubiquitous proteins with multiple roles in RNA metabolism including splicing and mRNA export. It is reasonable to assume that both ALYREF and YBX1 bind to many mRNAs that do not contain m5C.

To substantiate the author's claim that ALYREF or YBX1 binds m5C-modified RNAs to an extent that would allow distinguishing its binding to non-modified RNAs from binding to m5C-modified RNAs, it would be recommended to provide data on the affinity of these, supposedly proven, m5C readers to non-modified versus m5C-modified RNAs. To do so, this reviewer suggests performing experiments as described in Slama et al., 2020 (doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.10.020). However, using dot blots like in so many published studies to show modification of a specific antibody or protein binding, is insufficient as an argument because no antibody, nor protein, encounters nanograms to micrograms of a specific RNA identity in a cell. This issue remains a major caveat in all studies using so-called RNA modification reader proteins as bait for detecting RNA modifications in epitranscriptomics research. It becomes a pertinent problem if used as a platform for base editing similar to the work presented in this manuscript.

The authors have tried to address the point made by this reviewer. However, rather than performing an experiment with recombinant ALYREF-fusions and m5C-modified to unmodified RNA oligos for testing the enrichment factor of ALYREF in vitro, the authors resorted to citing two manuscripts. One manuscript is cited by everybody when it comes to ALYREF as m5C reader, however none of the experiments have been repeated by another laboratory. The other manuscript is reporting on YBX1 binding to m5C-containing RNA and mentions PAR-CLiP experiments with ALYREF, the details of which are nowhere to be found in doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y.

Furthermore, the authors have added RNA pull-down assays that should substitute for the requested experiments. Interestingly, Figure S1E shows that ALYREF binds equally well to unmodified and m5C-modified RNA oligos, which contradicts doi:10.1038/cr.2017.55, and supports the conclusion that wild-type ALYREF is not specific m5C binder. The necessity of including always an overexpression of ALYREF-mut in parallel DRAM experiments, makes the developed method better controlled but not easy to handle (expression differences of the plasmid-driven proteins etc.)

Thank you for pointing this out. First, we would like to correct our previous response: the binding ability of ALYREF to m5C-modified RNA was initially reported in doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.55, (and not in doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y), where it was observed through PAR-CLIP analysis that the K171 mutation weakens its binding affinity to m5C -modified RNA.

Our previous experimental approach was not optimal: the protein concentration in the INPUT group was too high, leading to overexposure in the experimental group. Additionally, we did not conduct a quantitative analysis of the results at that time. In response to your suggestion, we performed RNA pull-down experiments with YBX1 and ALYREF, rather than with the pan-DRAM protein, to better validate and reproduce the previously reported findings. Our quantitative analysis revealed that both ALYREF and YBX1 exhibit a stronger affinity for m5C -modified RNAs. Furthermore, mutating the key amino acids involved in m5C recognition significantly reduced the binding affinity of both readers. These results align with previous studies (doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.55 and doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0361-y), confirming that ALYREF and YBX1 are specific readers of m5C -modified RNAs. However, our detection system has certain limitations. Despite mutating the critical amino acids, both readers retained a weak binding affinity for m5C, suggesting that while the mutation helps reduce false positives, it is still challenging to precisely map the distribution of m5C modifications. To address this, we plan to further investigate the protein structure and function to obtain a more accurate m5C sequencing of the transcriptome in future studies. Accordingly, we have updated our results and conclusions in lines 294-299 and discuss these limitations in lines 109-114.

In addition, while the m5C assay can be performed using only the DRAM system alone, comparing it with the DRAMmutC control enhances the accuracy of m5C region detection. To minimize the variations in transfection efficiency across experimental groups, it is recommended to use the same batch of transfections. This approach not only ensures more consistent results but also improve the standardization of the DRAM assay, as discussed in the section added on line 308-312.

(2) Using sodium arsenite treatment of cells as a means to change the m5C status of transcripts through the downregulation of the two major m5C writer proteins NSUN2 and NSUN6 is problematic and the conclusions from these experiments are not warranted. Sodium arsenite is a chemical that poisons every protein containing thiol groups. Not only do NSUN proteins contain cysteines but also the base editor fusion proteins. Arsenite will inactivate these proteins, hence the editing frequency will drop, as observed in the experiments shown in Figure 5, which the authors explain with fewer m5C sites to be detected by the fusion proteins.

The authors have not addressed the point made by this reviewer. Instead the authors state that they have not addressed that possibility. They claim that they have revised the results section, but this reviewer can only see the point raised in the conclusions. An experiment would have been to purify base editors via the HA tag and then perform some kind of binding/editing assay in vitro before and after arsenite treatment of cells.

We appreciate the reviewer’s insightful comment. We fully agree with the concern raised. In the original manuscript, our intention was to use sodium arsenite treatment to downregulate NSUN mediated m5C levels and subsequently decrease DRAM editing efficiency, with the aim of monitoring m5C dynamics through the DRAM system. However, as the reviewer pointed out, sodium arsenite may inactivate both NSUN proteins and the base editor fusion proteins, and any such inactivation would likely result in a reduced DRAM editing. This confounds the interpretation of our experimental data.

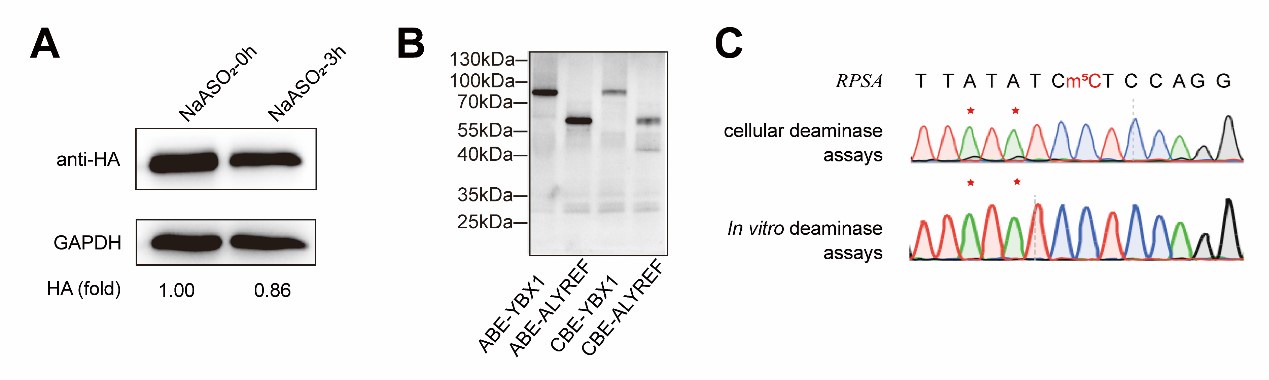

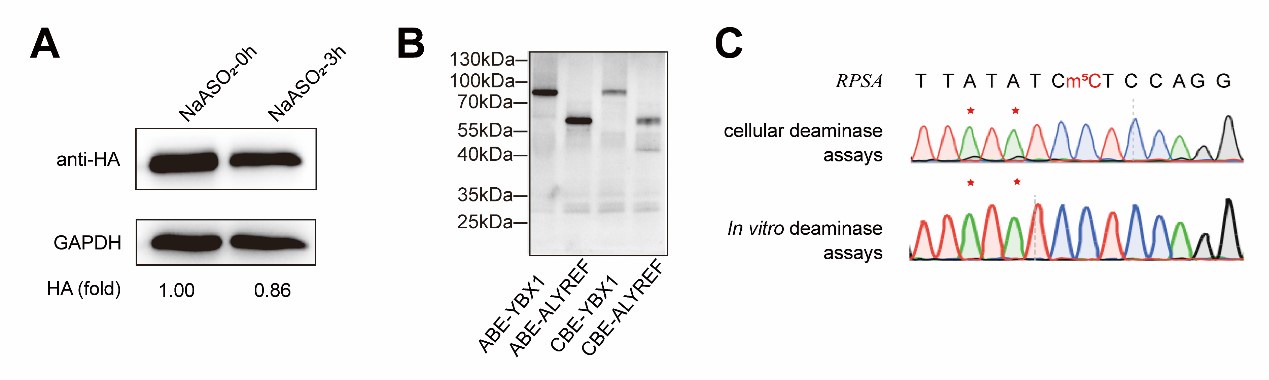

As demonstrated in Appendix A, western blot analysis confirmed that sodium arsenite indeed decreased the expression of fusion proteins. In addition, we attempted in vitro fusion protein purification using multiple fusion tags (HIS, GST, HA, MBP) for DRAM fusion protein expression, but unfortunately, we were unable to obtain purified proteins. However, using the Promega TNT T7 Rapid Coupled In Vitro Transcription/Translation Kit, we successfully purified the DRAM protein (Appendix B). Despite this success, subsequent in vitro deamination experiments did not yield the expected mutation results (Appendix C), indicating that further optimization is required. This issue is further discussed in line 314-315.

Taken together, the above evidence supports that the experiment of sodium arsenite treatment was confusing and we determined to remove the corresponding results from the main text of the revised manuscript.

Author response image 1.

(3) The authors should move high-confidence editing site data contained in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 into one of the main Figures to substantiate what is discussed in Figure 4A. However, the data needs to be visualized in another way then excel format. Furthermore, Supplementary Table 2 does not contain a description of the columns, while Supplementary Table 3 contains a single row with letters and numbers.

The authors have not addressed the point made by this reviewer. Figure 3F shows the screening process for DRAM-seq assays and principles for screening high-confidence genes rather than the data contained in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 of the former version of this manuscript.

Thank you for your valuable suggestion. We have visualized the data from Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 in Figure 4A as a circlize diagram (described in lines 213-216), illustrating the distribution of mutation sites detected by the DRAM system across each chromosome. Additionally, to improve the presentation and clarity of the data, we have revised Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 by adding column descriptions, merging the DRAM-ABE and DRAM-CBE sites, and including overlapping m5C genes from previous datasets.