Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorMihaela IordanovaConcordia University, Montreal, Canada

- Senior EditorYanchao BiPeking University, Beijing, China

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The novel advance by Wang et al is in the demonstration that, relative to a standard extinction procedure, the retrieval-extinction procedure more effectively suppresses responses to a conditioned threat stimulus when testing occurs just minutes after extinction. The authors provide solid evidence to show that this "short-term" suppression of responding involves engagement of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Strengths:

Overall, the study is well-designed and the results are valuable. There are, however, a few issues in the way that it is introduced and discussed. It would have been useful if the authors could have more explicitly related the results to a theory - it would help the reader understand why the results should have come out the way that they did. More specific comments are presented below.

Please note: The authors appear to have responded to my original review twice. It is not clear that they observed the public review that I edited after the first round of revisions. As part of these edits, I removed the entire section titled Clarifications, Elaborations and Edits

Theory and Interpretation of Results

(1) It is difficult to appreciate why the first trial of extinction in a standard protocol does NOT produce the retrieval-extinction effect. This applies to the present study as well as others that have purported to show a retrieval-extinction effect. The importance of this point comes through at several places in the paper. E.g., the two groups in study 1 experienced a different interval between the first and second CS extinction trials; and the results varied with this interval: a longer interval (10 min) ultimately resulted in less reinstatement of fear than a shorter interval. Even if the different pattern of results in these two groups was shown/known to imply two different processes, there is nothing in the present study that addresses what those processes might be. That is, while the authors talk about mechanisms of memory updating, there is little in the present study that permits any clear statement about mechanisms of memory. The references to a "short-term memory update" process do not help the reader to understand what is happening in the protocol.

In reply to this point, the authors cite evidence to suggest that "an isolated presentation of the CS+ seems to be important in preventing the return of fear expression." They then note the following: "It has also been suggested that only when the old memory and new experience (through extinction) can be inferred to have been generated from the same underlying latent cause, the old memory can be successfully modified (Gershman et al., 2017). On the other hand, if the new experiences are believed to be generated by a different latent cause, then the old memory is less likely to be subject to modification. Therefore, the way the 1st and 2nd CS are temporally organized (retrieval-extinction or standard extinction) might affect how the latent cause is inferred and lead to different levels of fear expression from a theoretical perspective." This merely begs the question: why might an isolated presentation of the CS+ result in the subsequent extinction experiences being allocated to the same memory state as the initial conditioning experiences?

This is not addressed in the paper. The study was not designed to address this question; and that the question did not need to be addressed for the set of results to be interesting. However, understanding how and why the retrieval-extinction protocol produces the effects that it does in the long-term test of fear expression would greatly inform our understanding of how and why the retrieval-extinction protocol has the effects that it does in the short-term tests of fear expression. To be clear; the results of the present study are very interesting - there is no denying that. I am not asking the authors to change anything in response to this point. It simply stands as a comment on the work that has been done in this paper and the area of research more generally.

(2) The discussion of memory suppression is potentially interesting but raises many questions. That is, memory suppression is invoked to explain a particular pattern of results but I, as the reader, have no sense of why a fear memory would be better suppressed shortly after the retrieval-extinction protocol compared to the standard extinction protocol; and why this suppression is NOT specific to the cue that had been subjected to the retrieval-extinction protocol. I accept that the present study was not intended to examine aspects of memory suppression, and that it is a hypothesis proposed to explain the results collected in this study. I am not asking the authors to change anything in response to this point. Again, it simply stands as a comment on the work that has been done in this paper.

(3) The authors have inserted the following text in the revised manuscript: "It should be noted that while our long-term amnesia results were consistent with the fear memory reconsolidation literatures, there were also studies that failed to observe fear prevention (Chalkia, Schroyens, et al., 2020; Chalkia, Van Oudenhove, et al., 2020; Schroyens et al., 2023). Although the memory reconsolidation framework provides a viable explanation for the long-term amnesia, more evidence is required to validate the presence of reconsolidation, especially at the neurobiological level (Elsey et al., 2018). While it is beyond the scope of the current study to discuss the discrepancies between these studies, one possibility to reconcile these results concerns the procedure for the retrieval-extinction training. It has been shown that the eligibility for old memory to be updated is contingent on whether the old memory and new observations can be inferred to have been generated by the same latent cause (Gershman et al., 2017; Gershman and Niv, 2012). For example, prevention of the return of fear memory can be achieved through gradual extinction paradigm, which is thought to reduce the size of prediction errors to inhibit the formation of new latent causes (Gershman, Jones, et al., 2013). Therefore, the effectiveness of the retrieval-extinction paradigm might depend on the reliability of such paradigm in inferring the same underlying latent cause." ***It is perfectly fine to state that "the effectiveness of the retrieval-extinction paradigm might depend on the reliability of such paradigm in inferring the same underlying latent cause..." This is not uninteresting; but it also isn't saying much. Ideally, the authors would have included some statement about factors that are likely to determine whether one is or isn't likely to see a retrieval-extinction effect, grounded in terms of the latent state theories that have been invoked here. Presumably, the retrieval-extinction protocol has variable effects because of procedural differences that affect whether subjects infer the same underlying latent cause when shifted into extinction. Surely, the clinical implications of any findings are seriously curtailed unless one understands when a protocol is likely to produce an effect; and why the effect occurs at all? This question is rhetorical. I am not asking the authors to change anything in response to this point. Again, it stands as a comment on the work that has been done in this paper; and remains a comment after insertion of the new text, which is acknowledged and appreciated.

(4) The authors find different patterns of responses to CS1 and CS2 when they were tested 30 min after extinction versus 24 h after extinction. On this basis, they infer distinct memory update mechanisms. However, I still can't quite see why the different patterns of responses at these two time points after extinction need to be taken to infer different memory update mechanisms. That is, the different patterns of responses at the two time points could be indicative of the same "memory update mechanism" in the sense that the retrieval-extinction procedure induces a short-term memory suppression that serves as the basis for the longer-term memory suppression (i.e., the reconsolidation effect). My pushback on this point is based on the notion of what constitutes a memory update mechanism; and is motivated by what I take to be a rather loose use of language/terminology in the reconsolidation literature and this paper specifically (for examples, see the title of the paper and line 2 of the abstract).

To be clear: I accept the authors' reply that "The focus of the current manuscript is to demonstrate that the retrieval-extinction paradigm can also facilitate a short-term fear memory deficit measured by SCR". However, I disagree with the claim that any short-term fear memory deficit must be indicative of "update mechanisms other than reconsolidation", which appears on Line 27 in the abstract and very much indicates the spirit of the paper. To make the point: the present study has examined the effectiveness of a retrieval-extinction procedure in suppressing fear responses 30 min, 6 hours and 24 hours after extinction. There are differences across the time points in terms of the level of suppression, its cue specificity, and its sensitivity to manipulation of activity in the dlPFC. This is perfectly interesting when not loaded with additional baggage re separable mechanisms of memory updating at the short and long time points: there is simply no evidence in this study or anywhere else that the short-term deficit in suppression of fear responses has anything whatsoever to do with memory updating. It can be exactly what is implied by the description: a short-term deficit in the suppression of fear responses. Again, this stands as a comment on the work that has been done; and remains a comment for the revised paper.

(5) It is not clear why thought control ability ought to relate to any aspect of the suppression that was evident in the 30 min tests - that is, I accept the correlation between thought control ability and performance in the 30 min tests but would have liked to know why this was looked at in the first place and what, if anything, it means. The issue at hand is that, as best as I can tell, there is no theory to which the result from the short- and long-term tests can be related. The attempts to fill this gap with reference to phenomena like retrieval-induced forgetting are appreciated but raise more questions than answers. This is especially clear in the discussion, where it is acknowledged/stated: "Inspired by the similarities between our results and suppression-induced declarative memory amnesia (Gagnepain et al., 2017), we speculate that the retrieval-extinction procedure might facilitate a spontaneous memory suppression process and thus yield a short-term amnesia effect. Accordingly, the activated fear memory induced by the retrieval cue would be subjected to an automatic fear memory suppression through the extinction training (Anderson and Floresco, 2022)." There is nothing in the subsequent discussion to say why this should have been the case other than the similarity between results obtained in the present study and those in the literature on retrieval induced forgetting, where the nature of the testing is quite different. Again, this is simply a comment on the work that has been done - no change is required for the revised paper.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary

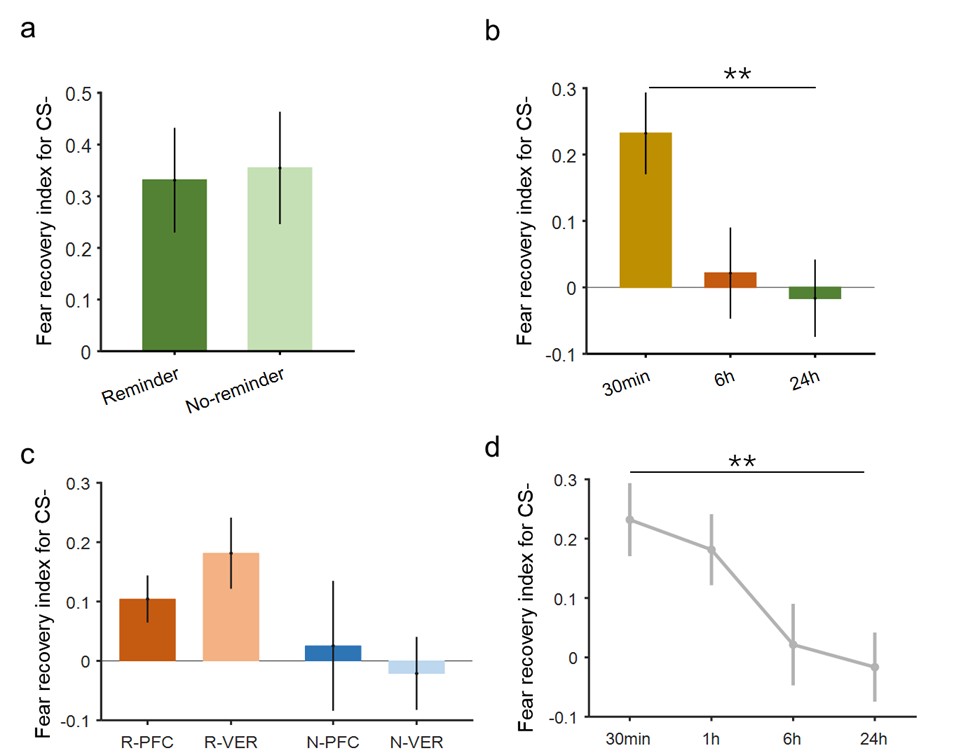

The study investigated whether memory retrieval followed soon by extinction training results in a short-term memory deficit when tested - with a reinstatement test that results in recovery from extinction - soon after extinction training. Experiment 1 documents this phenomenon using a between-subjects design. Experiment 2 used a within-subject control and sees that the effect is also observed in a control condition. In addition, it also revealed that if testing is conducted 6 hours after extinction, there is not effect of retrieval prior to extinction as there is recovery from extinction independently of retrieval prior to extinction. A third Group also revealed that retrieval followed by extinction attenuates reinstatement when the test is conducted 24 hours later, consistent with previous literature. Finally, Experiment 3 used continuous theta-burst stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and assessed whether inhibition of that region (vs a control region) reversed the short-term effect revealed in Experiments 1 and 2. The results of control groups in Experiment 3 replicated the previous findings (short-term effect), and the experimental group revealed that these can be reversed by inhibition of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Strengths

The work is performed using standard procedures (fear conditioning and continuous theta-burst stimulation) and there is some justification of the sample sizes. The results replicate previous findings - some of which have been difficult to replicate and this needs to be acknowledged - and suggest that the effect can also be observed in a short-term reinstatement test.

The study establishes links between the memory reconsolidation and retrieval-induced forgetting (or memory suppression) literatures. The explanations that have been developed for these are distinct and the current results integrate these, by revealing that the DLPFC activity involved in retrieval-extinction short-term effect. There is thus some novelty in the present results, but numerous questions remain unaddressed.

Weakness

The fear acquisition data is converted to a differential fear SCR and this is what is analysed (early vs late). However, the figure shows the raw SCR values for CS+ and CS- and therefore it is unclear whether acquisition was successful (despite there being an "early" vs "late" effect - no descriptives are provided).

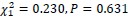

In Experiment 1 (Test results) it is unclear whether the main conclusion stems from a comparison of the test data relative to the last extinction trial ("we defined the fear recovery index as the SCR difference between the first test trial and the last extinction trial for a specific CS") or the difference relative to the CS- ("differential fear recovery index between CS+ and CS-"). It would help the reader assess the data if Fig 1e presents all the indexes (both CS+ and CS-). In addition, there is one sentence which I could not understand "there is no statistical difference between the differential fear recovery indexes between CS+ in the reminder and no reminder groups (P=0.048)". The p value suggests that there is a difference, yet it is not clear what is being compared here. Critically, any index taken as a difference relative to the CS- can indicate recovery of fear to the CS+ or absence of discrimination relative to the CS-, so ideally the authors would want to directly compare responses to the CS+ in the reminder and no-reminder groups. In the absence of such comparison, little can be concluded, in particular if SCR CS- data is different between groups. The latter issue is particularly relevant in Experiment 2, in which the CS- seems to vary between groups during the test and this can obscure the interpretation of the result.

In experiment 1, the findings suggest that there is a benefit of retrieval followed by extinction in a short-term reinstatement test. In Experiment 2, the same effect is observed to a cue which did not undergo retrieval before extinction (CS2+), a result that is interpreted as resulting from cue-independence, rather than a failure to replicate in a within-subjects design the observations of Experiment 1 (between-subjects). Although retrieval-induced forgetting is cue-independent (the effect on items that are supressed [Rp-] can be observed with an independent probe), it is not clear that the current findings are similar, and thus that the strong parallels made are not warranted. Here, both cues have been extinguished and therefore been equally exposed during the critical stage.

The findings in Experiment 2 suggest that the amnesia reported in experiment 1 is transient, in that no effect is observed when the test is delayed by 6 hours. The phenomena whereby reactivated memories transition to extinguished memories as a function of the amount of exposure (or number of trials) is completely different from the phenomena observed here. In the former, the manipulation has to do with the number of trials (or total amount of time) that the cues are exposed. In the current Experiment 2, the authors did not manipulate the number of trials but instead the retention interval between extinction and test. The finding reported here is closer to a "Kamin effect", that is the forgetting of learned information which is observed with intervals of intermediate length (Baum, 1968). Because the Kamin effect has been inferred to result from retrieval failure, it is unclear how this can be explained here. There needs to be much more clarity on the explanations to substantiate the conclusions.

There are many results (Ryan et al., 2015) that challenge the framework that the authors base their predictions on (consolidation and reconsolidation theory), therefore these need to be acknowledged. These studies showed that memory can be expressed in the absence of the biological machinery thought to be needed for memory performance. The authors should be careful about statements such as "eliminate fear memores" for which there is little evidence.

The parallels between the current findings and the memory suppression literature are speculated in the general discussion, and there is the conclusion that "the retrieval-extinction procedure might facilitate a spontaneous memory suppression process". Because one of the basic tenets of the memory suppression literature is that it reflects an "active suppression" process, there is no reason to believe that in the current paradigm the same phenomenon is in place, but instead it is "automatic". In other words, the conclusions make strong parallels with the memory suppression (and cognitive control) literature, yet the phenomena that they observed is thought to be passive (or spontaneous/automatic). Ultimately, it is unclear why 10 mins between the reminder and extinction learning will "automatically" supress fear memories. Further down in the discussion it is argued that "For example, in the well-known retrieval-induced forgetting (RIF) phenomenon, the recall of a stored memory can impair the retention of related long-term memory and this forgetting effect emerges as early as 20 minutes after the retrieval procedure, suggesting memory suppression or inhibition can occur in a more spontaneous and automatic manner". I did not follow with the time delay between manipulation and test (20 mins) would speak about whether the process is controlled or automatic. In addition, the links with the "latent cause" theoretical framework are weak if any. There is little reason to believe that one extinction trial, separated by 10 mins from the rest of extinction trials, may lead participants to learn that extinction and acquisition have been generated by the same latent cause.

Among the many conclusions, one is that the current study uncovers the "mechanism" underlying the short-term effects of retrieval-extinction. There is little in the current report that uncovers the mechanism, even in the most psychological sense of the mechanism, so this needs to be clarified. The same applies to the use of "adaptive".

Whilst I could access the data in the OFS site, I could not make sense of the Matlab files as there is no signposting indicating what data is being shown in the files. Thus, as it stands, there is no way of independently replicating the analyses reported.

The supplemental material shows figures with all participants, but only some statistical analyses are provided, and sometimes these are different from those reported in the main manuscript. For example, the test data in Experiment 1 is analysed with a two-way ANOVA with main effects of group (reminder vs no-reminder) and time (last trial of extinction vs first trial of test) in the main report. The analyses with all participants in the sup mat used a mixed two-way ANOVA with group (reminder vs no reminder) and CS (CS+ vs CS-). This makes it difficult to assess the robustness of the results when including all participants. In addition, in the supplementary materials there are no figures and analyses for Experiment 3.

One of the overarching conclusions is that the "mechanisms" underlying reconsolidation (long term) and memory suppression (short term) phenomena are distinct, but memory suppression phenomena can also be observed after a 7-day retention interval (Storm et al., 2012), which then questions the conclusions achieved by the current study.

References:

Baum, M. (1968). Reversal learning of an avoidance response and the Kamin effect. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 66(2), 495.

Chalkia, A., Schroyens, N., Leng, L., Vanhasbroeck, N., Zenses, A. K., Van Oudenhove, L., & Beckers, T. (2020). No persistent attenuation of fear memories in humans: A registered replication of the reactivation-extinction effect. Cortex, 129, 496-509.

Ryan, T. J., Roy, D. S., Pignatelli, M., Arons, A., & Tonegawa, S. (2015). Engram cells retain memory under retrograde amnesia. Science, 348(6238), 1007-1013.

Storm, B. C., Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2012). On the durability of retrieval-induced forgetting. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 24(5), 617-629.

Comments on revisions:

Thanks to the authors for trying to address my concerns.

(1 and 2) My point about evidence for learning relates to the fact that in none of the experiments an increase in SCR to the CSs+ is observed during training (in Experiment 1 CS+/CS- differences are even present from the outset), instead what happens is that participants learn to discriminate between the CS+ and CS- and decrease their SCR responding to the safe CS-. This begs the question as to what is being learned, given that the assumption is that the retrieval-extinction treatment is concerned with the excitatory memory (CS+) rather than the CS+/CS- discrimination. For example, Figures 6A and 6B have short/Long term amnesia in the right axes, but it is unclear from the data what memory is being targeted. In Figure 6C, the right panels depicting Suppression and Reconsolidation mechanisms suggest that it is the CS+ memory that is being targeted. Because the dependent measure (differential SCR) captures how well the discrimination was learned (this point relates to point 2 which the authors now acknowledge that there are differences between groups in responding to the CS-), then I struggle to see how the data supports these CS+ conclusions. The fact that influential papers have used this dependent measure (i.e., differential SCR) does not undermine the point that differences between groups at test are driven by differences in responding to the CS-.

(3, 4 and 5) The authors have qualified some of the statements, yet I fail to see some of these parallels. Much of the discussion is speculative and ultimately left for future research to address.

(6) I can now make more sense of the publicly available data, although the files would benefit from an additional column that distinguishes between participants that were included in the final analyses (passed the multiple criteria = 1) and those who did not (did not pass the criteria = 0). Otherwise, anyone who wants to replicate these analyses needs to decipher the multiple inclusion criteria and apply it to the dataset.