Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorAndrea MartinMax Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- Senior EditorYanchao BiPeking University, Beijing, China

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors quantified information in gesture and speech, and investigated the neural processing of speech and gestures in pMTG and LIFG, depending on their informational content, in 8 different time-windows, and using three different methods (EEG, HD-tDCS and TMS). They found that there is a time-sensitive and staged progression of neural engagement that is correlated with the informational content of the signal (speech/gesture).

Strengths:

A strength of the paper is that the authors attempted to combine three different methods to investigate speech-gesture processing.

Weaknesses:

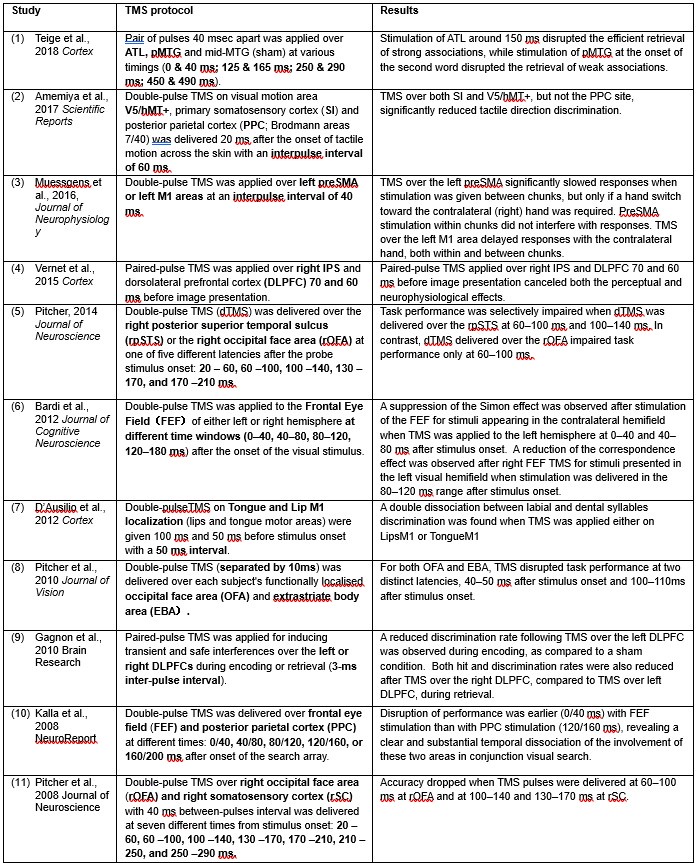

(1) One major issue is that there is a tight anatomical coupling between pMTG and LIFG. Stimulating one area could therefore also result in stimulation of the other area (see Silvanto and Pascual-Leone, 2008). I therefore think it is very difficult to tease apart the contribution of these areas to the speech-gesture integration process, especially considering that the authors stimulate these regions in time windows that are very close to each other in both time and space (and the disruption might last longer over time).

(2) Related to this point, it is unclear to me why the HD-TDCS/TMS is delivered in set time windows for each region. How did the authors determine this, and how do the results for TMS compare to their previous work from 2018 and 2023 (which describes a similar dataset+design)? How can they ensure they are only targeting their intended region since they are so anatomically close to each other?

(3) As the EEG signal is often not normally distributed, I was wondering whether the authors checked the assumptions for their Pearson correlations. The authors could perhaps better choose to model the different variables to see whether MI/entropy could predict the neural responses. How did they correct the many correlational analyses that they have performed?

(4) The authors use ROIs for their different analyses, but it is unclear why and on the basis of what these regions are defined. Why not consider all channels without making them part of an ROI, by using a method like the one described in my previous comment?

(5) The authors describe that they have divided their EEG data into a "lower half" and a "higher half" (lines 234-236), based on entropy scores. It is unclear why this is necessary, and I would suggest just using the entropy scores as a continuous measure.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The study is an innovative and fundamental study that clarified important aspects of brain processes for integration of information from speech and iconic gesture (i.e., gesture that depicts action, movement, and shape), based on tDCS, TMS, and EEG experiments. They evaluated their speech and gesture stimuli in information-theoretic ways and calculated how informative speech is (i.e., entropy), how informative gesture is, and how much shared information speech and gesture encode. The tDCS and TMS studies found that the left IFG and pMTG, the two areas that were activated in fMRI studies on speech-gesture integration in the previous literature, are causally implicated in speech-gesture integration. The size of tDC and TMS effects are correlated with the entropy of the stimuli or mutual information, which indicates that the effects stem from the modulation of information decoding/integration processes. The EEG study showed that various ERP (event-related potential, e.g., N1-P2, N400, LPC) effects that have been observed in speech-gesture integration experiments in the previous literature, are modulated by the entropy of speech/gesture and mutual information. This makes it clear that these effects are related to information decoding processes. The authors propose a model of how the speech-gesture integration process unfolds in time, and how IFG and pMTG interact with each other in that process.

Strengths:

The key strength of this study is that the authors used information theoretic measures of their stimuli (i.e., entropy and mutual information between speech and gesture) in all of their analyses. This made it clear that the neuro-modulation (tDCS, TMS) affected information decoding/integration and ERP effects reflect information decoding/integration. This study used tDCS and TMS methods to demonstrate that left IFG and pMTG are causally involved in speech-gesture integration. The size of tDCS and TMS effects are correlated with information-theoretic measures of the stimuli, which indicate that the effects indeed stem from disruption/facilitation of the information decoding/integration process (rather than generic excitation/inhibition). The authors' results also showed a correlation between information-theoretic measures of stimuli with various ERP effects. This indicates that these ERP effects reflect the information decoding/integration process.

Weaknesses:

The "mutual information" cannot fully capture the interplay of the meaning of speech and gesture. The mutual information is calculated based on what information can be decoded from speech alone and what information can be decoded from gesture alone. However, when speech and gesture are combined, a novel meaning can emerge, which cannot be decoded from a single modality alone. When example, a person produces a gesture of writing something with a pen, while saying "He paid". The speech-gesture combination can be interpreted as "paying by signing a cheque". It is highly unlikely that this meaning is decoded when people hear speech only or see gestures only. The current study cannot address how such speech-gesture integration occurs in the brain, and what ERP effects may reflect such a process. Future studies can classify different types of speech-gesture integration and investigate neural processes that underlie each type. Another important topic for future studies is to investigate how the neural processes of speech-gesture integration change when the relative timing between the speech stimulus and the gesture stimulus changes.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

In this useful study, Zhao et al. try to extend the evidence for their previously described two-step model of speech-gesture integration in the posterior Middle Temporal Gyrus (pMTG) and Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG). They repeat some of their previous experimental paradigms, but this time quantifying Information-Theoretical (IT) metrics of the stimuli in a stroop-like paradigm purported to engage speech-gesture integration. They then correlate these metrics with the disruption of what they claim to be an integration effect observable in reaction times during the tasks following brain stimulation, as well as documenting the ERP components in response to the variability in these metrics.

The integration of multiple methods, like tDCS, TMS, and ERPs to provide converging evidence renders the results solid. However, their interpretation of the results should be taken with care, as some critical confounds, like difficulty, were not accounted for, and the conceptual link between the IT metrics and what the authors claim they index is tenuous and in need of more evidence. In some cases, the difficulty making this link seems to arise from conceptual equivocation (e.g., their claims regarding 'graded' evidence), whilst in some others it might arise from the usage of unclear wording in the writing of the manuscript (e.g. the sentence 'quantitatively functional mental states defined by a specific parser unified by statistical regularities'). Having said that, the authors' aim is valuable, and addressing these issues would render the work a very useful approach to improve our understanding of integration during semantic processing, being of interest to scientists working in cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging.

The main hurdle to achieving the aims set by the authors is the presence of the confound of difficulty in their IT metrics. Their measure of entropy, for example, being derived from the distribution of responses of the participants to the stimuli, will tend to be high for words or gestures with multiple competing candidate representations (this is what would presumptively give rise to the diversity of responses in high-entropy items). There is ample evidence implicating IFG and pMTG as key regions of the semantic control network, which is critical during difficult semantic processing when, for example, semantic processing must resolve competition between multiple candidate representations, or when there are increased selection pressures (Jackson et al., 2021). Thus, the authors' interpretation of Mutual Information (MI) as an index of integration is inextricably contaminated with difficulty arising from multiple candidate representations. This casts doubt on the claims of the role of pMTG and IFG as regions carrying out gesture-speech integration as the observed pattern of results could also be interpreted in terms of brain stimulation interrupting the semantic control network's ability to select the best candidate for a given context or respond to more demanding semantic processing.

In terms of conceptual equivocation, the use of the term 'graded' by the authors seems to be different from the usage commonly employed in the semantic cognition literature (e.g., the 'graded hub hypothesis', Rice et al., 2015). The idea of a graded hub in the controlled semantic cognition framework (i.e., the anterior temporal lobe) refers to a progressive degree of abstraction or heteromodal information as you progress through the anatomy of the region (i.e., along the dorsal-to-ventral axis). The authors, on the other hand, seem to refer to 'graded manner' in the context of a correlation of entropy or MI and the change in the difference between Reaction Times (RTs) of semantically congruent vs incongruent gesture-speech. The issue is that the discourse through parts of the introduction and discussion seems to conflate both interpretations, and the ideas in the main text do not correspond to the references they cite. This is not overall very convincing. What is it exactly the authors are arguing about the correlation between RTs and MI indexes? As stated above, their measure of entropy captures the spread of responses, which could also be a measure of item difficulty (more diverse responses imply fewer correct responses, a classic index of difficulty). Capturing the diversity of responses means that items with high entropy scores are also likely to have multiple candidate representations, leading to increased selection pressures. Regions like pMTG and IFG have been widely implicated in difficult semantic processing and increased selection pressures (Jackson et al., 2021). How is this MI correlation evidence of integration that proceeds in a 'graded manner'? The conceptual links between these concepts must be made clearer for the interpretation to be convincing.