Planaria: Genes for regeneration

Planarian flatworms are well known for their amazing regenerative capacity. In a manner reminiscent of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, chopping one worm into little pieces will result in a dish full of tiny worms regenerated from the fragments in just a few days. In recent years this system has been rediscovered as an experimental model for probing how and why tissues regenerate, with the hope that this will help us to improve tissue repair in our own bodies.

Regeneration in planarians depends on the presence of stem cells called neoblasts. These cells are distributed throughout the body and, when part of the worm has been amputated, they are activated to reform the tissues that have been removed (Wagner et al., 2011). It is still not entirely clear how the stem cells regenerate specific organs. Are there different types of stem cell that form different tissues? Do signals produced by nearby cells cause specific tissues to form? Or is a combination of both stem cell bias and local signalling used? Now, in eLife, Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado and colleagues at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research—including Carolyn Adler as first author—have provided new insights into this question by developing a method to specifically remove the pharynx, the feeding organ of the worm, to study organ-specific regeneration (Adler et al., 2014).

The pharynx itself contains no stem cells and cannot regenerate the rest of the worm (Figure 1). However, a worm without a pharynx can rapidly regenerate this rather complex organ. Adler et al. found that incubating flatworms in sodium azide caused the pharynx to be ejected from the body without affecting the rest of the worm, thus allowing them to monitor the process of pharynx regeneration. Blocking stem cell function by irradiation, or by RNA interference knockdown of stem cell-specific genes, prevented regeneration, which suggests that neoblasts have a crucial role in the regeneration of the pharynx.

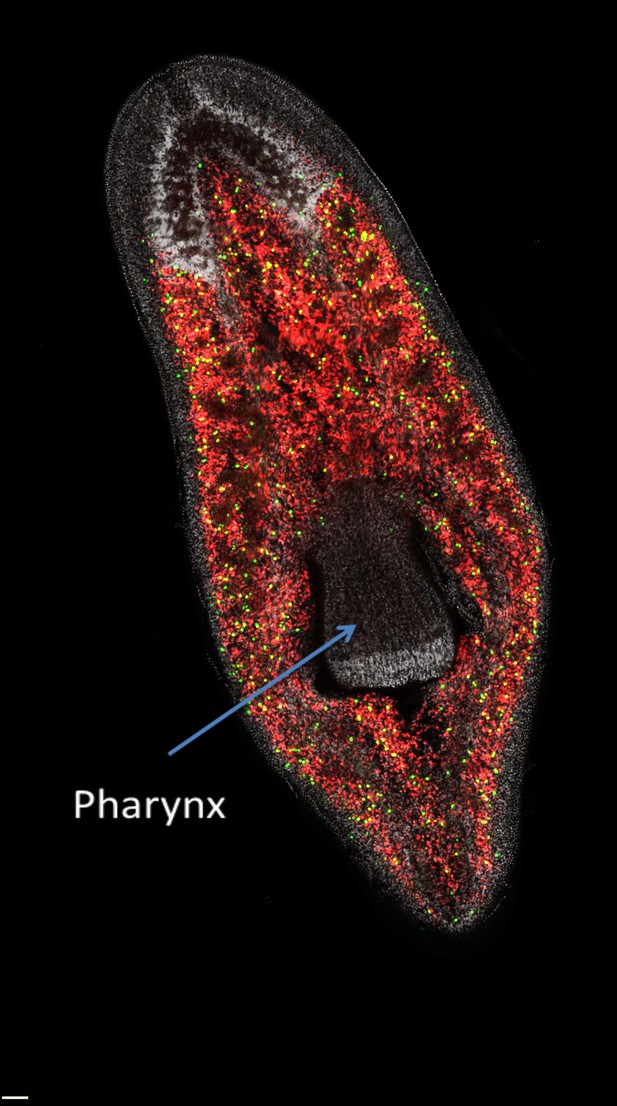

The distribution of neoblasts in a planarian.

Neoblasts are found throughout the body but are excluded from the pharynx. The image distinguishes between neoblasts that are in the process of dividing to form new cells (green dots) and those that are not dividing (red dots) in a freshwater planarian called Schmidtea mediterranea. If the pharynx is removed, the actively dividing neoblasts and their progeny will migrate to the damaged area and begin organ regeneration.

Image courtesy of Alex Lin and Bret Pearson.

Local changes in gene expression at the wound site during the early phases of regeneration revealed that 356 genes were consistently expressed at higher levels than they were under normal conditions. The importance of each of these genes for regeneration was then tested by employing RNA interference knockdown to inhibit their expression, and using the ability of the planarian to feed as a simple way of measuring how well its pharynx had regenerated. Twenty genes affected feeding behaviour significantly; some affected general stem cell function; other genes affected feeding behaviour but did not affect tissue regeneration; and a small subset of genes specifically affected how the pharynx formed and functioned. The most severe but specific defects in pharynx formation were seen with the knockdown of the gene that encodes a Forkhead transcription factor called FoxA.

Forkhead proteins encoded by the FoxA gene family have important roles in specifying the tissues of the digestive system of invertebrates and vertebrates (Kaestner, 2010). In the simple sea anemone, FoxA marks the cells that will go on to form the pharynx (Fritzenwanker et al., 2004), while in the roundworm C. elegans, the equivalent of FoxA is key to specifying the different cell types found in the pharynx during development (Horner et al., 1998). In vertebrates, FoxA genes have switched from regulating the pharynx, the entry point to the intestine, to regulating the cells of the intestine itself (Ang et al., 1993).

In mammals, the FoxA family of transcription factors has also picked up other functions. These include specifying cell fate in the notochord and floorplate, structures that are crucial for axis formation in the developing embryo (Ang and Rossant, 1994; Weinstein et al., 1994), and controlling the function of adult neurons that produce dopamine (Stott et al., 2013). These divergent functions presumably relate to the fact that FoxA proteins are so-called pioneer factors. Pioneer factors bind to DNA at specific sites, opening up the chromatin structure in many different contexts (Zaret and Carroll, 2011). This means that they can function in combination with different transcription factors in different tissues. As a pioneer factor, FoxA may have played a fundamental evolutionary role in coordinating the formation of the structures needed to ingest and process food in multicellular organisms, and has then retained and expanded that role throughout evolution.

Planarian FoxA is expressed in the developing and the mature pharynx, and also in scattered neoblast cells around the pharynx that cluster at the site of amputation. In the absence of FoxA, neoblasts are still present, but they fail to migrate to the amputation site and initiate regeneration, and instead appear to be misdirected to other sites. So is FoxA primarily required for correct cell migration or for correct organ specification? In C. elegans, the equivalent of FoxA (which is called Pha-4) has been shown to bind directly to a wide range of genes that are required for pharynx structure and function (Gaudet and Mango, 2002), suggesting that it has a fundamental role in specifying pharynx cell fate. It will be very interesting to explore the direct targets of FoxA in planarians to see if it has a similar master regulatory function. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the evolutionarily conserved function of FoxA lies in regulating particular types of cell migration and rearrangement during development, rather than primarily in specifying cell fate (de-Leon, 2011). Since cell behaviour and cell fate are closely intertwined, it is hard to separate these functions. However, a more detailed comparison of the targets of FoxA at different stages of planarian regeneration with the corresponding targets in other species could reveal the fundamental roles of this important transcription factor.

References

-

The formation and maintenance of the definitive endoderm lineage in the mouse: involvement of HNF3/forkhead proteinsDevelopment 119:1301–1315.

-

pha-4, an HNF-3 homolog, specifies pharyngeal organ identity in Caenorhabditis elegansGenes & Development 12:1947–1952.https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.12.13.1947

-

The FoxA factors in organogenesis and differentiationCurrent Opinion in Genetics & Development 20:527–532.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2010.06.005

-

Pioneer transcription factors: establishing competence for gene expressionGenes & Development 25:2227–2241.https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.176826.111

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2014, Rossant

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 30,978

- views

-

- 560

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 3

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.02517

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

Learning more about the genes that allow flatworms to regenerate organs and tissue after amputation.