Reproduction: A kiss to set the rhythm

In animals, fertility and reproduction are highly regulated processes that depend on several hormones interacting in a strictly choreographed and rhythmic manner. This regulation starts a long time before birth and is maintained throughout the life of an individual, even after they are no longer fertile (Boehm et al., 2015; Clarke and Dhillo, 2016). However, the system also needs to flexibly adjust to changes including pregnancy, ageing and the availability of food. How is this complex and intricate balance of hormones maintained in the body?

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) is the main regulator of fertility and is produced by a group of neurons in a region of the brain called the hypothalamus. This hormone causes cells in the pituitary gland to release several other hormones that regulate the production of sex cells and sex hormones in the gonads. In turn, the sex hormones can also affect the release of GnRH and some pituitary hormones (Cimino et al., 2016; Herbison, 2016).

GnRH is generally released from the hypothalamus in pulses that are crucial for reproduction (Moenter, 2015). This pulsatile release can only be achieved if many GnRH-producing neurons are able to coordinate their activity to release the hormone at the same time, but it was not clear how this is achieved. Now, in eLife, Jian Qiu and colleagues – who are based at the Oregon Health and Science University and the University of Washington – report that neurons in the hypothalamus that produce a protein called kisspeptin can synchronize their activity and activate GnRH neurons (Qiu et al., 2016).

A previous study suggested that a group of kisspeptin-producing neurons in a brain region called the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus – called Kiss1ARH neurons for short – might be responsible for generating the GnRH pulses (Okamura et al., 2013). However, there is also a non-pulsatile surge in GnRH release in females before they ovulate. This surge appears to be driven by other groups of kisspeptin neurons (referred to as Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons) in two other parts of the hypothalamus (Herbison, 2016). A recent tracing study suggests that Kiss1ARH neurons do not have any direct contact with the cell bodies of GnRH neurons, but may instead be linked to them via Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons (Yip et al., 2015).

Qiu et al. used a technique called optogenetics to investigate how kisspeptin neurons control the release of GnRH in mice. Genetically modifying the mice to express a light-sensitive ion channel protein called channelrhodopsin in their Kiss1ARH neurons allowed Qiu et al. to activate these neurons with beams of light. This “photostimulation” of Kiss1ARH neurons produced electrical activity in these cells known as a slow excitatory post synaptic potential. This electrical activity seemed to depend on inputs from other Kiss1ARH neurons and relied on two receptor proteins that detect the neurotransmitters neurokinin B and dynorphin, which are released by Kiss1ARH neurons. Furthermore, the photostimulation of Kiss1ARH neurons on one side of the brain produced slow excitatory post synaptic potentials in Kiss1ARH neurons on the other side of the brain.

Further experiments revealed that photostimulating Kiss1ARH neurons can produce activity in the GnRH neurons of mice. Drugs that activate a neurokinin B receptor protein on Kiss1ARH neurons also have a similar effect in mouse brain slices, which suggests that Kiss1ARH neurons activate each other to stimulate GnRH neurons. Qiu et al. also show that Kiss1ARH neurons stimulate GnRH neurons by activating Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons (Figure 1).

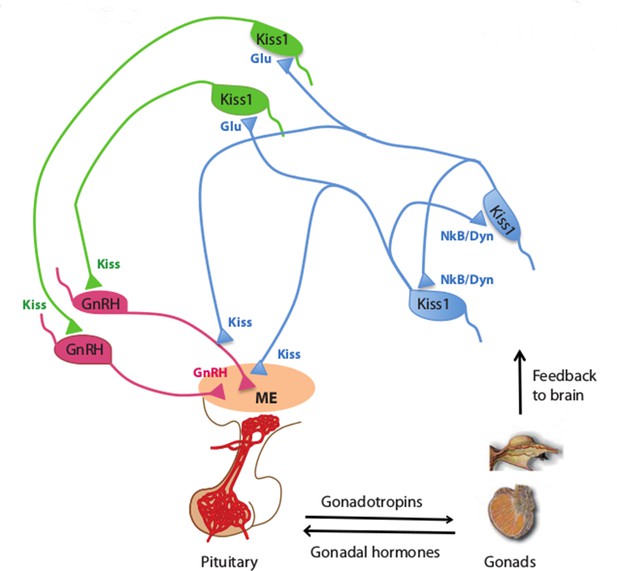

Kisspeptin neurons coordinate the release of hormones that regulate reproduction.

In mammals, several hormones interact to regulate fertility and reproduction. Gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) is released by neurons (pink) in an area of the brain called the median eminence (ME; peach oval), which is part of the hypothalamus. This triggers the release of gonadotrophin and other hormones from the pituitary gland, which leads to the production of sex cells and sex (gonadal) hormones in the gonads. In turn, the gonads provide feedback to the system by regulating the release of GnRH (not shown) and gonadotrophin. Qiu et al. found that kisspeptin neurons in the hypothalamus synchronize their activity and drive GnRH neuronal activity. Kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (KissARH neurons; blue) activate other KissARH neurons by releasing two neurotransmitters called neurokinin B (NkB) and dynorphin (Dyn). These neurons also activate kisspeptin neurons in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus and the periventricular preoptic nucleus (Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons; green) in a pathway that involves another neurotransmitter called glutamate (Glu). In turn, the Kiss1AVPV/PeN neurons contact the cell body of GnRH neurons to stimulate the release of GnRH (Glanowska and Moenter, 2015). KissARH neurons can also directly contact the fibers of GnRH neurons in the arcuate nucleus (Ciofi et al., 2006), which has been proposed to stimulate GnRH release without involving the cell body of GnRH neurons.

Together, these findings suggest that Kiss1ARH neurons on both sides of the brain coordinate their activity to stimulate the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus. Further work is needed to find out if this synchronization is sufficient to regulate the pulsatile release of GnRH. The photoactivation stimulus used in this study triggered very strong activity in the Kiss1ARH neurons: are there any inputs to Kiss1ARH neurons in normal mice that can trigger similarly high levels of activity? A future challenge is to investigate whether the kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus set the pattern of GnRH pulses, or whether they simply relay synchronized patterns that they receive from other neurons (Israel et al., 2014; Marder et al., 2014).

References

-

Kisspeptin across the human lifespan:evidence from animal studies and beyondJournal of Endocrinology 229:R83–98.https://doi.org/10.1530/JOE-15-0538

-

Control of puberty onset and fertility by gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronsNature Reviews Endocrinology 12:452–466.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2016.70

-

Kisspeptin and GnRH pulse generationAdvances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 784:297–323.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6199-9_14

Article and author information

Author details

Publication history

Copyright

© 2016, Shruti et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 1,477

- views

-

- 203

- downloads

-

- 3

- citations

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Citations by DOI

-

- 3

- citations for umbrella DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.19823